Velma Bolyard Paper Artist - New York State, USA

You make paper from many different natural sources discuss two very different papers and discuss the comparisons and differences between the two.

When I moved to New York’s North Country I was astonished by the cold climate and wild mountain feel of the place. One way I became familiar with the land here was by walking out and around, hiking and strolling and looking for plants useful to me as a fibre artist and papermaker. All three kinds of useful fibres for papermaking (leaf, bast, and seed) are found here.

A stark contrast can be found comparing milkweed (asclepias syriaca) and slippery elm (ulmus rubra). Milkweed bast is strong, lustrous, and easy to process. It can be gathered any time after the plant has reached full growth, field retted milkweed is very useful, as is freshly gathered fibre. The paper can be white, greenish, golden, or grey, depending on when it’s collected. Slippery elm can only be harvested in months that don’t have Rs in them (May-Aug.). It yields a reddish-brown, fairly coarse paper that is delightful to work with.

Is the colour of the original material always predominant in the paper or are there many that come out unexpected?

There are no rules about the colours of botanical papers, you can always have surprises. Interestingly enough, many papers, especially if they are in the green range fade to lovely tans and browns. Chlorophyll green is not permanent.

Do you blend natural resources to produce a single paper?

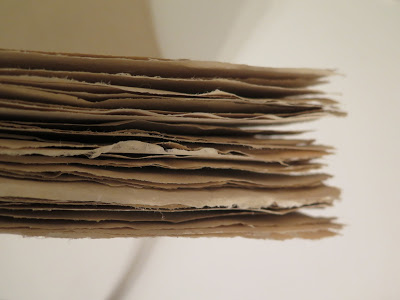

Most of the time I don’t blend pulps, but often, at the end of a session when I have used several pulps in a given time frame I make what is called “badger paper”, a tradition that comes from European mills where they would mix the leftover pulps at the end of the day or week. This paper was considered inferior (because of the lack of consistency) but in fact it can be quite interesting.

Two wild Badger sheets, cotton rag, Hosta Koza and Honeysuckle

Where did you first learn to make paper?

I began making paper in 1977 in art school at SUNY College at Buffalo, where I was a fibre art student. Papermaking was in the beginning of a huge revival at that time, and I made a LOT of paper in my one class. After that it was a couple of years before I was able to set up a paper mill of my own. It was challenging to downsize to a studio as most equipment was industrial or for large hand paper mills, and only a few papermakers were making botanical papers, and one book by Lilian Bell was my guide. My early teachers include some of the “big names” in the handpaper world.

What is it about handmade paper that keeps a hold on you?

It has to be the combination of matter and spirit, processing a fiber that will transform into a piece of paper has NEVER lost it’s fascination for me. And I get to make beautiful work with my papers. I love finding new ways to make paper and books more and more beautiful: dyeing processes, sewing, printing, and spinning and weaving paper (shifu) are all what I am currently working with.

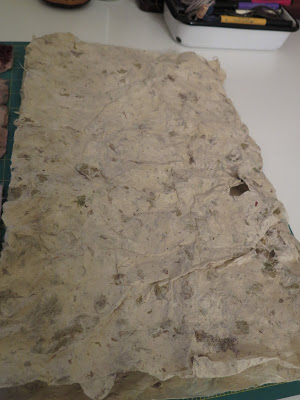

Joomchi Kozo with hand spun wool

Discuss how you weave with paper.

The blending of the two crafts papermaking and weaving.

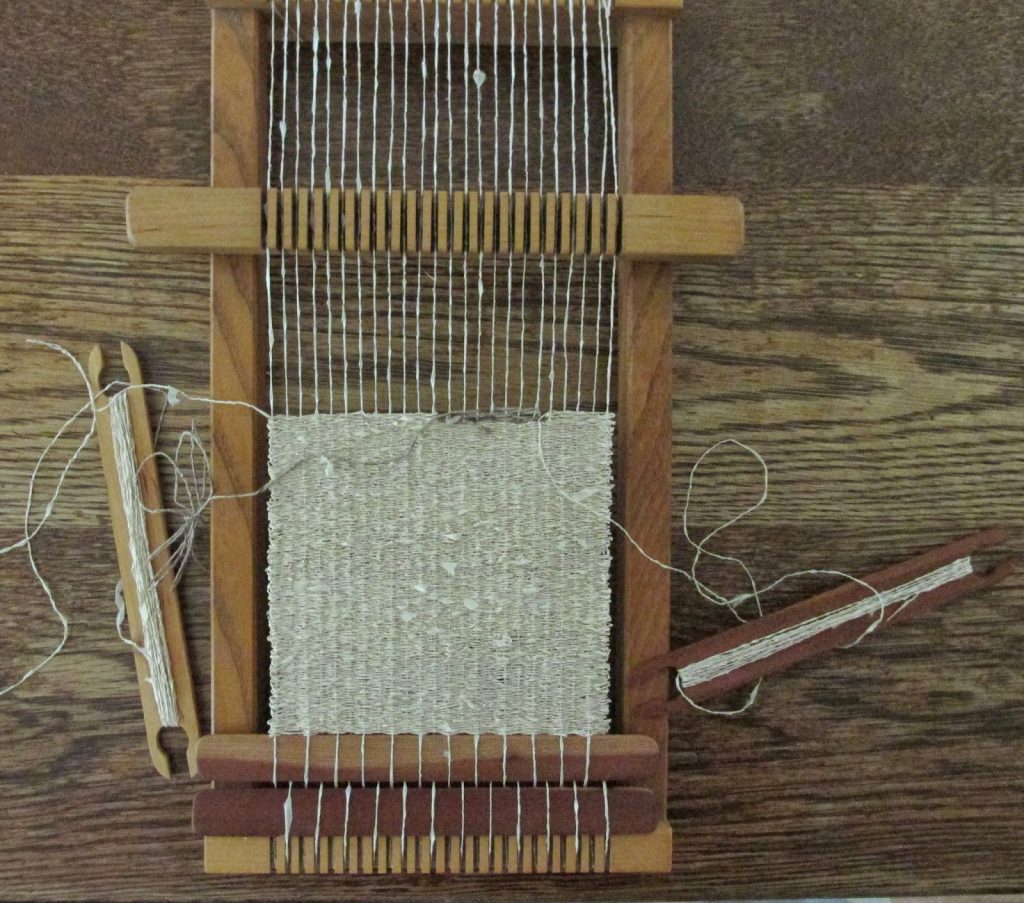

Making shifu (a spun and woven paper textile) and kami-ito (hand spun paper thread) is something that a handful of people have been exploring; the art at its highest form is of course from Japan (where the words shifu and kami-ito are from). Because it takes quite a long time to make shifu, I weave only narrow widths, mostly in the 15-inch-wide or smaller range. The lengths vary according to need. I make some ¾ inch tiny shifu squares, too.

Shifu is made from a sheet of fine handmade paper, traditionally kozo (a Japanese mulberry), that is folded and cut into narrow 1-3 or 4 mm continuous strips that are then spun into thread called kami-ito. Kami-ito is then woven into cloth, shifu often has warp made from another fibre such as silk or cotton.

Making my paper expressly for shifu making is something I only do once in a while. I often use kozo or lokta for my kami-ito.

Expand on your Wooden Book series and how this evolved?

Sometimes I make books with wooden covers, usually with coptic bindings, but these do not contain shifu so far. My shaped shifu books are all bound in vellum or the shifu acts as the cover for larger book with handmade and printed pages. The larger books often are reinforced by sewing the shifu to a strong flax case paper.

You call your studio ‘My Mill’ expand on the terminology.

I have studio spaces in my house for dry processes and for dyeing.

The mill is a separate building, and houses all of my papermaking equipment, including the hydraulic press, moulds and deckles, fibre, a Hollander beater, floor drains and sinks, storage and drying boards. There is enough area and tables to teach in. I once squeezed in 24 people for a very amazing class.

Your paper has taken you to many places. Discuss the joy of sharing your knowledge through your classes?

Fibre and paper have been the vehicle for so much. It’s taken me to Canada and across the US and three times to Australia; I go again in March where I’m teaching a 6-day master class at the Grampians Texture, as well as a few smaller classes. I worked making paper alone for many years here in my mill, selling to a few folks who knew and loved my papers, making smaller works, and exhibiting mostly locally. I was a single mother and worked as a special education teacher for many years. It’s only been since the I began blogging that my work became known and I have been asked to teach in many venues in North America and Australia.

While travelling for classes how has the local flora influenced your art practice?

I usually bring along paper that I know will succeed for whatever work we’re exploring, and I am often teaching shifu and book arts so it’s imperative that I have paper that works. This year the 2017 Grampians class will focus on handmade papers, which will be a change. I look forward to using plants that I don’t know yet.

Hand papermaking is a sustainable process if you treat the harvest with respect personal thoughts?

This means several things:

-cultivating your own plants if you can

-asking your friends to give you their pruning’s

-never take from public lands without explicit permission

-never harvest any plant in excess unless you are eradicating an invasive

-always ask, always thank

-and that asking and thanking includes addressing the plants themselves.

Without gratitude we have nothing, without the earth’s rich plants we would die. It’s best to always remember this.

Contact details

Velma Boylard

velmabolyard.blogspot.com

Velma Boylard, New York State, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, January, 2017

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: