Tasha Lewis Sculptor - New York, USA

Tasha Lewis, New York, USA

Tasha Lewis explains how she showed her art around the world. The Swam went from the South Pole to her home city, New York.

Zoneone Arts brings Tasha Lewis to you…

Discuss the work you are producing for Ebb Tide at the Magic Garden in Philadelphia.

Number of pieces

The show will take place over two gallery spaces and in one courtyard which connects them. I will be presenting 16 figurative works and 29 vessels of varying forms and sizes. For the first time I created a concrete translation of my process, so one of my largest vessels will be outside.

Tidal Bather II 18 x 37 x 15 inches

The story behind the work

In my representational sculptural practice, I use fiber techniques to articulate a female mythology driven by imperfect and resilient female figures. I have chosen fabric as my central material because like the skin, it can be pierced and sewn, adorned and torn; its surface acts as a ground for storytelling. I am specifically drawn to the symbol of the female bather because bodies of water denote liminality, vulnerability and oneness. I reclaim the poses of Greek Goddesses by recreating them with casts of my own body. Further, I install these life-sized bathers alongside plaster vessels replicating classical pottery shapes associated with water and cleansing ceremonies.

The element of water is itself present in my work through hand-dyed color gradients. By dyeing each form with varying shades from their feet up, they bear the mark of a waterline reminiscent of a rising or falling tide. While distant in some ways, Classical Greek culture was not so different from our own; we still live in a patriarchal system that imposes rules and expectations on women’s bodies. Like the sea’s effect on coasts, this caustic atmosphere is manifest through an erosion of form and through my beading and embroidery. These embellishments simultaneously conjure jewelry, nets, and armor. I seek to conjure a complex vision of contemporary female experience by connecting my practice with previous generations of women who also sought self-actualization through their stitches.

Silver Crown, 19 x 25 x 17 inches

The techniques you have used

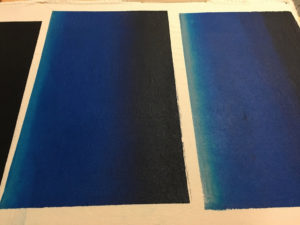

The primary technique for this show is mixed-media sculpture, some mostly cardboard and newspaper others mostly plaster, covered in a hand sewn skin of dyed fabric. For a few pieces the skin is a cyanotype print of a gradient, but for most it is an ombré achieved by applying various colors / intensities of a dye paste with a silk screen.

Most of us have, to quietly admit that we haven’t competed reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. Discuss your eight weeks with James Joyce.

How did it come about?

Ulysses is one of my favorite books, and since I graduated from University in 2012 I have observed Bloomsday, June 16th, which is the day on which the novel is set and during which I attempt to re-read the entire book. I don’t succeed, but it’s a fun way to focus in on a text that has so many layers and nuance. In any case, the book was bouncing around in my head one day in the spring of 2014 while I riding the NYC subway. I just casually thought that if I were ever to illustrate the text I would attempt to translate visually the various literary styles that Joyce uses for each chapter. There are 18 Chapters so I would need 18 different means of image creation that reflected the tone, context or key symbols present in the text. I made some notes in my notebook to pass the time. It became clear that to do this fantasy project I would need access to a print shop and a lot of time, neither of which I had at the time in my NYC life, so I shelved the idea for about 8 months. I found a call for entry from an artist friend for a residency in Eastport, Maine. They were looking for ambitious print-based projects that would inaugurate their 8 weeks fall residency in October and November of 2015. I proposed that I would illustrate every page of James Joyce’s Ulysses in 18 different styles and the rest is history.

What did you learn from the eight weeks?

The concentrated nature of the residency was such a blessing. I would not have completed this project without being totally immersed in Joyce. Almost every waking moment of the day I was reading Joyce or compiling images. Additionally, in the fall of 2015 I was still getting used to working full-time, so having this eight week test really helped me hone a routine and nurture my self-discipline when it comes to my studio practice.

What were some of the highlights?

I think the best surprise was how beautiful Eastport, Maine is. The town and its waterfront actually became a character in my watercolor illustrations (for chapter three) and a stand in for Dublin. I had the same sounds, many of the same smells: marsh grass, seaweed, gulls etc. I am sure that these elements added both to my serenity and stamina (because I love the ocean) but also allowed me to access new dimensions of the novel.

Another highlight was the open studio atmosphere, and indeed the studio itself. It was located right downtown across from a small pier. I could walk out and in 30 seconds I was above the crash of waves and looking out onto the water and the islands off the coast. It was a truly unique experience. I also had many curious visitors- some locals even started reading Ulysses while I was there. It was fun to engage with the community and force myself to stop for a few minutes and get out of my head. I have always found that in talking about my work I am actually continuing to process my ideas, and so even answering the most basic questions can lead to new epiphanies.

What gave you the most trouble?

There were a few chapters that were troublesome, but Circe was the most pronounced. Circe is probably the biggest hurdle in the text. It might seem like an easier chapter at first because it’s written in the style of a play and so it is less dense than some of the previous chapters, but a reader soon finds themselves swept into a quicksand of Dublin at midnight, a brothel, memories, hallucinations, dreams, and drunkenness. It’s chaos. The stage directions are grandiose and the characters keep shifting. I knew each of the illustrations would have to focus on a very specific element from the page, but I also wanted the chapter as a whole, to reflect the unstable, gritty nature of the section. In the end I was inspired to use a process I had never even heard of before called silk screen mono-printing. Essentially you draw on a silkscreen with pastel, water soluble crayons or markers and then take a clear ink base and squeegee the image onto your paper through the screen. The results were unpredictable. I worried about how constrained I felt in my drawing. I worried about how my images would translate. I worried about a lot of things until I realized that this chapter, which is such a slog to read, should make me feel all its anxieties. Indeed, I decided to just embrace all the unpredictability in the material and I think it made the images all the more striking, especially when viewed as a whole.

What was your final reaction?

I was very pleased with the final book. I was a bit amazed that I was able to complete the full suite of 644 pages plus 18 title pages in just over seven weeks.

If anyone is curious to find out, it is available on demand through my publisher:

https://store.bookbaby.com/book/Illustrating-Joyces-Ulysses

Look at the relationship between your Studio Art and English Literature degree and this project.

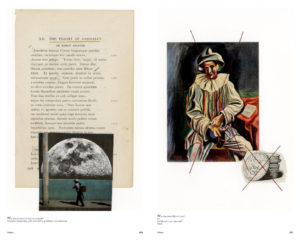

My dual degree is always part of my art practice, but the project to Illustrate Joyce’s Ulysses really was a dream combination. In school I often focused on writing about the art references in literature, so it was very exciting to have the opportunity to flip that and create my own visual responses to one of my favorite books. I should say also, that the format of the project is very researched. I chose each visual mode for the 18 chapters in order to reflect an essential piece of that section of the narrative. I drew on key themes, and the excerpted text is a reasonable abridgment of the book because I ended up being drawn to the most important moments or images of each page. I have presented the final work to academics and students, and their response has been quite positive. My hope is that it will become something that students use to access the text in a new way during their literature courses.

How did the book evolve?

Right as the residency concluded, I laid out a version of the book that was purely visual. All the images were in the correct order, but there was no text present. While I had selected the excerpts during the creation of the images, I had not yet digitized that hand-annotated text, and it would take me another few months to layout a new edition that included both text and image on each page. This eight pound edition feels quite like a text book, but it allows for the relationships between the text and the image to be assessed in real time by the viewer.

Can you take us through the process you use in your sculpture?

My sculptures are full of various media, but at the moment most of my work starts with a plaster gauze cast made from molds. I made a bunch of molds from my body and molds of vessels which I use as the bases for my current bodies of work. The plaster gauze is much stronger than plaster of Paris, and can be used to make hollow forms that are less prone to puncture or fracture if dropped. I further reinforce my work with inner skeletons of wood, wire, and mesh. There are also parts of my forms that have embedded felt so that when I stitch in the final skin I can stitch directly into the form. This is key in elements of concavity- belly buttons for example- or in small forms like toes or ears.

Kekythos III 7 x 18 x 7 inches

Separate from the sculptural practice, I also develop the surface design for the skin of the sculpture. While in previous bodies of work this was limited to cyanotype prints on cotton, I now work mostly with fiber reactive dyes applied with a silk screen. Where before I created negatives, I now work in color palettes and developing technique for ombre blending in the screen. While I will always have a place in my practice for cyanotype, the range of color I can achieve with the dye is quite magic, and it is really driving my practice forward at the moment.

Once I have the form and the raw textile I begin the patchwork of the skin. Depending on the pattern, I may need to cut shapes of fabric to work together to maintain a color gradient working up the pieces, or define a horizontal high tide line, or just create a solid base for further embellishment in the final step. In every case I place each patch down with a little bit of archival tape on the edge, stretching it around the form. Once I have placed the majority of patches, I will begin stitching them to each other. During the sewing process most of the tape is removed as it was only there to keep the tension even across the patchwork. The stitches are not fancy, I consider them a meditation and generally melt into the background once the layers of embellishment are added.

The final step in many of my sculptures is additional beading or embroidery. The beading has become especially important in my practice because the hard shiny elements create a stark contrast with the sewn fabric surface. The pearls came into my work as a kind of invasive species. Like barnacles, I saw them as taking over the skin of objects lost at sea. As I continued this body of work, the came also the represent our societies invasive and caustic environment toward women’s bodies. While I mimicked ancient artifacts with missing arms or heads, I was also attempting to capture the grating nature of societal pressure. Yet I did not want my female forms to surrender to these incursions. They may be partially ground down, but they are resilient. The beading and embroidery come to also represent forms of armor and jewelry.

Lekythos III, 7 x 18 x 7 inches

Discuss how you use stitch in your work.

Stitches are part of both the background and foreground in my work. Many pieces combine thread of varying weights, others have utilitarian stitches juxtaposing stitches used as purposeful mark making, still others have thread that was sewn into designs by an embroidery machine. The stitch is almost always a part of a meditative process with imbues the surface of the work with my labor and time.

Lekythos IV 4.5 x 15 x 4.5, Lekythos V 4.5 x 14.5 x 4.5, Lekythos VI 4 x 13 x 4,

Lekythos VII 4 x 13 x 4, Lekythos VIII 4 x 13 x 4,

Take two pieces using stitch to show the variation stitch can make.

In the top piece the stitch is used to mimic leg hair, the second it is used to mimic pubic hair. In both there are more utilitarian stitches that connect the patchwork base for the skins.

Tidal Bather VI, 20 x 45 x 14 inches

Tidal Bather VII, 16 x 31 x 14 inches

You left PA after your course and moved to New York, what instigated this move?

I moved both to be with my partner who had moved back to NYC and to pursue a studio residency at an artist run gallery space in Newark, New Jersey. I still have my main studio there five years later.

What has the move given you?

The fall after I arrived in NYC I was invited to participated in the Artist in the Marketplace program at the Bronx Museum. This professional development group became key to connecting with an artist community. Like most artists I have a complicated relationship with my adopted city. I am happy to be living on its periphery (in Jersey City on the other side of the Hudson) and to continue to work in Newark. I have a large space there and it has allowed me to tackle large projects and commissions I would have otherwise had to turn down.

Discuss ‘The Swam’

How are the butterflies made?

The butterflies are made from a double-sided cotton cyanotype print. By that I mean the image has been printed onto both the front and verso and the are registered together so that when the individual butterflies are cut out the image of the wing appears to go through the cloth. Once the cyanotypes are printed I dry them out and the cut out each butterfly by hand. The insects are then stiffened with a little fabric glue to give them a little weight. Once dried, I can sew a small magnet onto the belly. It is similar to sewing on a button.

The final result is a small blue creature that can alight on magnetic objects (iron, steel, tin etc.). Once I made the first 200, I just continued to add to them for 2 years.

Why have you use the word ‘swarm?

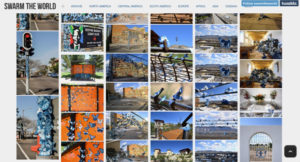

The Swarm began as a personal investigation of ephemeral street art in the summer of 2012. Swarm is both chaos and purpose. When animals swarm it is not random, it is often for the purpose of migration. There is huge cultural capitol in the symbol of butterflies, but in the end they are also strikingly beautiful. The blue, makes them almost alien, but also very attractive.

How did you use kickstart for this project?

After selecting the 220 participants in over 45 different countries I knew I would need to crowd source the international postage. The scope of the project was much bigger than I expected. Because of geography, some people’s postage dues would be triple or more that of others. I wanted to project to be accessible to everyone, so I set out to raise $10,000 to offset the country-to-country shipping with DHL. I incentivized donation with awards including postcards and butterflies from the project once it finished. It was successful and that money helped launch and sustain the project for its three year duration.

Where did you take / send the 15 packets of 350 butterflies?

I sent 15 packets of 350 butterflies to 15 geographic regions which each included 10-25 participants. The areas were: South America, Central America, West coast of North America, Central North America, Southern US and Caribbean, Eastern North America, Norther Isles, Iberian Peninsula, Central Europe, Africa, Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, South East Asia, Oceania, and Antartica.

How did you organise the images and videos of your swam?

I coordinated both a tumblr site and a dropbox site in order to archive the project. The first was public and each participant had access to upload content. The second was private and was used to gather larger resolution images that were used in the final publication.

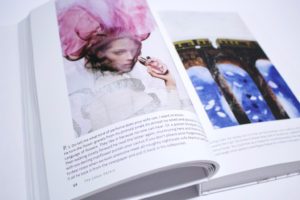

In the book I decided to organize the images geographically by region. Within those chapters I grouped the photographs by theme, contrasting contexts, similar or complementary color, scale or contrasting scales. I was focused on rhythm and flow from page to page.

What was the public’s reaction?

The public response was very positive. I think people enjoyed it now only for how expansive it was, but also how personal the symbol of the butterflies could be. The participants were particularly enthusiastic to collaborate with me and toe share the experience with people all over the world.

Why blue butterflies?

The butterflies are blue because they are made with the cyanotype process which naturally creates a blue and white image. The butterfly felt like the perfect symbol for such an ephemeral, yet global, project. These insects are resilient, beautiful and represent metamorphoses, rebirth and bring joy to many people. The image certainly brings joy to me.

Where are all the butterflies now?

About 2,000 of the 6,000 hand-made butterflies I sent out came back. Obviously many were lost, some in the mail some in the wind. The final swarm was divided into packets of 10 butterflies and is sold as part of a collectors edition with a signed and numbers hard cover copy of the book. They are available direct from my studio or through the Colossal store.

What was the effect of movement in this installation?

Because the main way people experienced this project is through still images, I set it up so there was dynamism in every other element. You would think that having blue butterflies in every picture would get boring, but my participants worked hard to find and showcase beautiful elements in their local environments.

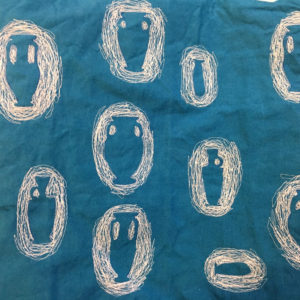

With Botanical Beast, discuss your knitting together of sculpture and fabric techniques.

In the past 6 years I have honed my sculptural technique, specifically the inner armature, and the Botanical Beasts represent a key turning point. This suite of works is made entirely with plaster gauze casts, wood, mesh and wire.

This collection is made up of 14 small heads and two large ones.

They are covered in botanical cyanotype prints made from pressed leaves and both the antlers and the thread I used to stitch them glow-in-the-dark.

Botanical Beast Group, Dark

What are your thoughts on combining techniques in a modern context?

I have always been driven by the combination of techniques, and I am so excited by the ‘maker movement’ and the new tools, especially the lazer cutters, which are available. I think it is such an exciting moment to be a sculptor. For me it is all about fit. I want to make elements of my work with my hands, but if a computer can cut out complicated shapes better than I can, I will use it. I have just scratched the surface of what is possible with iron-on laser cut fabric appliqué and computerized embroidery machines. In my next wave of work, I plan to focus on integrating even more of those elements.

Contact details:

Tasha Lewis

@TashaLewisArtist

http://illustratingulysses.com/

Tasha Lewis, New York, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September, 2018

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: