Susan Avishai Visual Artist

You have been working with textile waste for the past ten years. What lead you to this area of art?

Inspiration. My mother died in 2009 and the sad task of going through her belongings fell to me, her only daughter. She had been an artist as well, and was the one who had made sure that in childhood I had all the supplies I needed to be creative. So it seemed appropriate then, that her clothing became my medium too. I was expressing a longing for her, but in addition a respect for the way she presented herself in the world—always beautifully dressed (unlike her daughter with her paint-spattered yoga pants). It was hard to make the decision to cut up her garments, but as I handled them and reworked the fabric, and remembered the times she wore them, it was as though I was spending time with her once more, which I found enormously comforting.

Homage ll, 48” x 66” x 3” Deconstructed clothing, rope

At about the same time I became aware of the work of El Anatsui, the Ghanaian artist who creates tapestry-like hangings from bottlecaps. I travelled to NY in 2013 just to see his show, Gravity and Grace, at the Brooklyn Museum, and the work so moved me that at first I was speechless. I knew then that my years of photographic, rather intellectual realism in egg tempera, oil, and pencil were over. It was time to try something new, to press forward with what excited me, and to leave what was already well-practised and understood.

Medium. It was the utter transformation of detritus, trash, the no longer useful, into magnificent art, worthy of museum timed-entrances that spoke to me. My daughter Tamar describes it this way in her Lonely Palette podcast episode of El Anatsui [thelonelypalette.com/episodes/2017/3/1/episode-15-el-anatsuis-black-river-2009] “…the creativity that went into turning something that is so one thing into something so entirely different that you start thinking about the social and economic implications.” The artist said it himself: “The amazing thing about working with these ‘fabrics’ is that the poverty of the materials used in no way precludes the telling of rich and wonderful stories.”

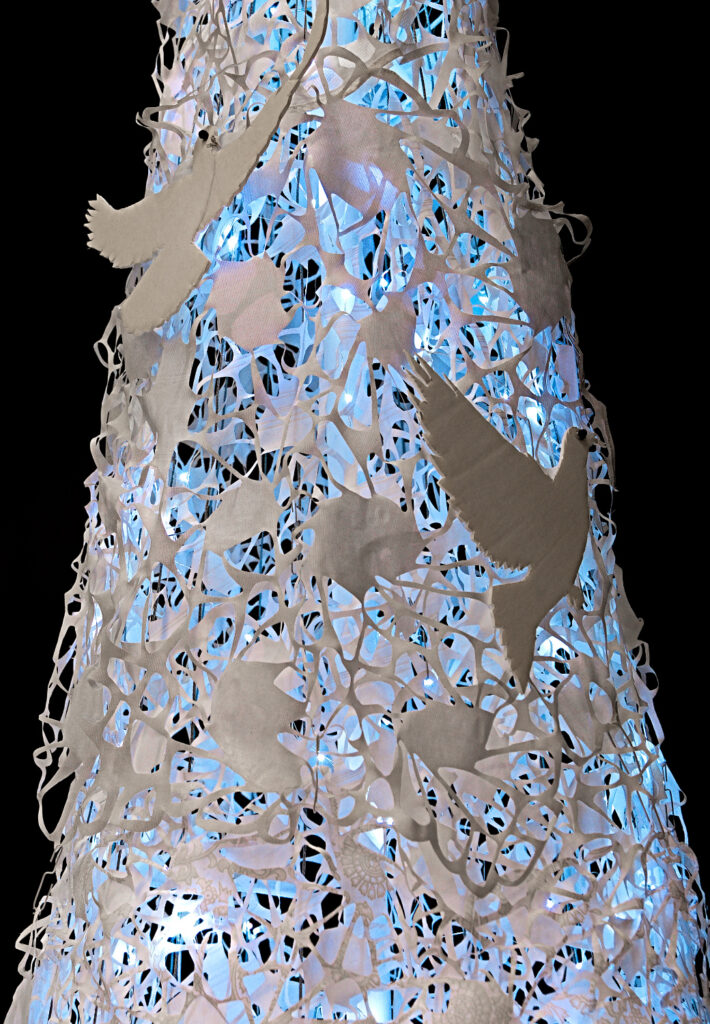

The repetition of like elements gave them rhythm and texture. This was a transformation so complete that it actually made me gasp when I saw what the elements actually were: discarded liquor bottle caps and collars. Several years later I got a similar thrill when, standing incognito behind some attendees at the Gardiner Museum Gala in Toronto, I overheard a comment about the doily-like intricacy of the 9’ fibre Christmas tree I had made. Then they read the blurb on the stand beside it. “What? This is made from men’s shirts?!” What I had learned from El Anatsui was that you need to make a stunner first, and only reveal the dirty secret afterwards– that this isn’t gold leaf or metallic threads; it’s bottle caps. This isn’t fine lace from France; it’s shirts from thrift shops.

Twice Blessed, 108” x 38” x 38” Deconstructed and stiffened white men’s shirt backs, acrylic base, wire, turnbolts, styrofoam, fairy lights.

I had needed a medium in which to be expansive: something ubiquitous, something cheap, something original. After making those first homages to my mother, the medium declared itself, of course: cast-off clothing. One only has to be paying attention, it seems. I’d bring home armfuls of shirts from thrift shops, rummage sales, and friends’ closet clean-outs. I’d deconstruct them and end up with piles of collars and cuffs, pockets and plackets, yokes and seams. Why shirts? Unlike women’s clothing with its many fabrics, colours, and designs, there was a predictability, a sameness about men’s shirts. The fabric was easy to work with, the same thin, crisp cotton I remember being so aware of when my father had hugged me. Every man I knew wore shirts; they were the uniform of work. They smelled of ironing, or piney deodorant, of labour and stress, of stability and love.

Message. Then I happened upon a small book entitled Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion by Elizabeth Cline and my eyes were opened to an uncomfortable global paradox. Garment manufacture had turned into a lightning quick cycle of Third World underpaid women, using flimsy fabric, simple pattern, and knock-off design to keep Western consumers supplied with cheap clothes. Worn briefly and discarded quickly, the waste we created made my head spin. The Council for Textile Recycling reports that the US alone generates 25 billion pounds of textile waste a year– 82 pounds per person!—and most of it is thrown into landfill. Now more than ever I needed to insert myself into this cycle of exploitation and waste, to increase awareness of and express my distress over the vast quantities of “stuff” we thoughtlessly toss away, how quickly we determine its usage to be over, and its value gone. By up-cycling, I wanted to see if I could create something transformative, inspired, sometimes even whimsical. I don’t think I speak only for myself when I think we connect with material on a deeper level when we recognize its previous life, its inherent history. It’s one thing to behold a fibre sculpture, but another to recognize it is made with the shirt cuffs you button each day.

Expand how you created sculptures from textiles?

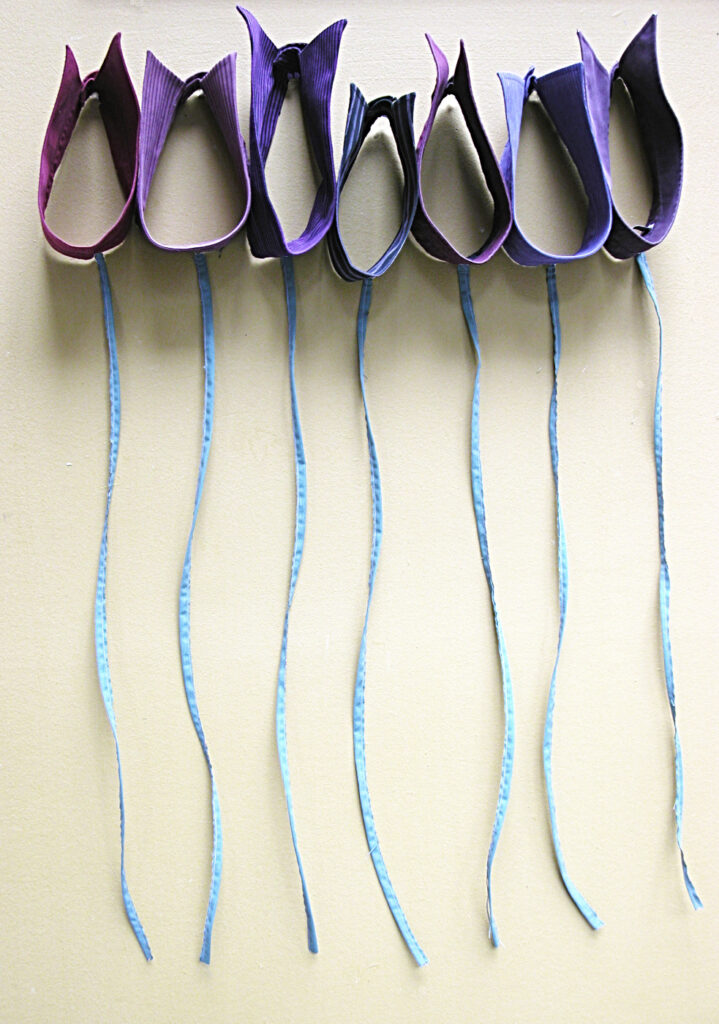

I’m not a schooled weaver, knitter, embroiderer or quilter; my techniques are simple—cutting, sewing, gluing. For me, fibre sculpture is more about making something I’ve never seen before, from parts of shirts we see every day. I let the deconstructed pieces suggest how they might be reconstructed. I would turn a buttoned collar around and it looked like a tulip Row.

Tulip Row, 32”x30”x3” Deconstructed men’s dress shirt collars, hems, glue.

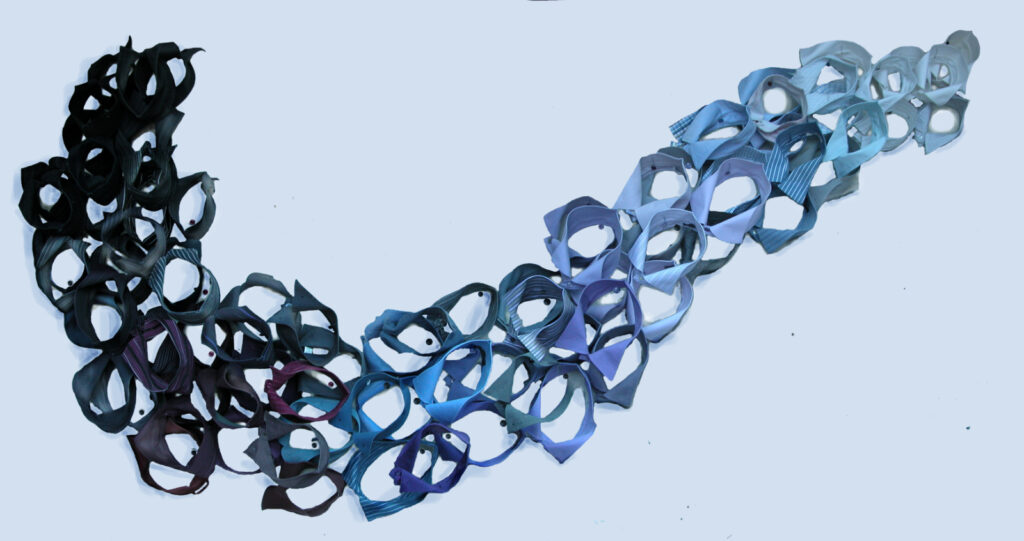

or a fish.

Off to School, 48” x 62” x 3.5” Deconstructed men’s shirt collars stiffened with polymer medium, wire, buttons, thread.

Then it was simply a matter of figuring out a way to make the piece…should it hang from a wall or from the ceiling? Did the collar need to be shaped with wire? Did the cuff need to be stiffened with acrylic medium?

Cuff’d, 27” x 24” x 4” Deconstructed men’s dress shirt cuffs, stiffening medium, glue.

Cuff’d, 27” x 24” x 4” Deconstructed men’s dress shirt cuffs, stiffening medium, glue.

How did colour play into the piece?

I was playing in the sand and it was important to drop any hesitation or pre-judgment, to let the passion and original approaches fly. Seams and hems turned into hundreds of . White shirt backs, painted with medium were hand cut and layered, the result resembling lace.

Garden without Seasons (2014)—70” x 28” x 4” deconstructed men’s shirts, glue, sewing

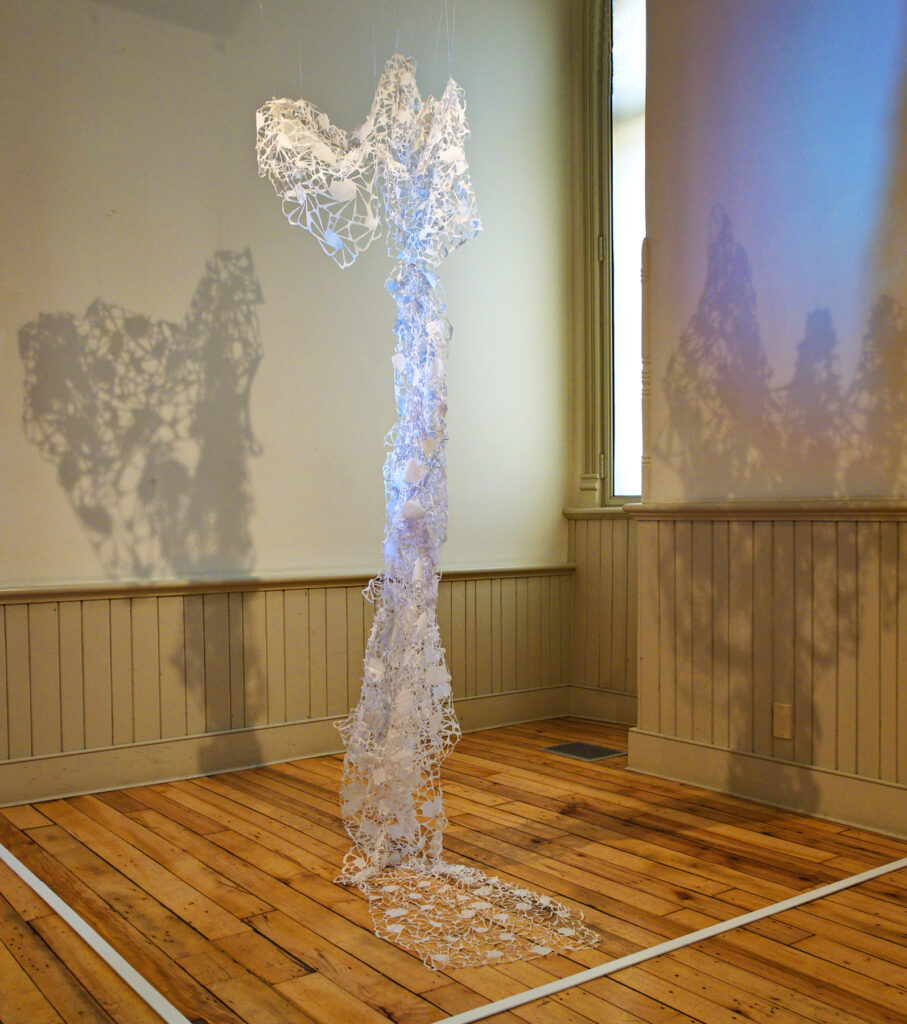

On a lark I pinned them from the ceiling, fastening the pieces to each other with paper clips and they seemed to transform themselves into a bridal gown.

“…and the Bride Wore White” 8’ x 14” x 12” deconstructed men’s dress shirts

embedded with polymer medium, paper clips and filament line to attach; hand cutting with scissors, sewing.

I often got excited by the shadows thrown on walls when the work was illuminated, and in this particular case the larger dark shadow attached to the gown became a Father-Daughter dance.

Expand upon how ‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel’ came to be.

I had begun quilting elements with holes one summer in my studio, not at all sure what they would become. Hundreds were strung on curtain rods. After arranging and rearranging them in varied formations on the floor, I decided to attach them as a long train of sorts, and it ended up to be 37 feet in length. It was affixed to our 3rd floor ceiling, tumbling down through the stairwell, and puddling on the first floor. Easy to see where the title came from. Over fifty shirts in colours that graduated from white to black through purple hues sacrificed their lives for this one. The piece has been configured differently in several exhibitions, sometimes threaded through with tiny fairy lights.

Rapunzel, Rapunzel 400” x 18” x4” Deconstructed, quilted men’s shirt pieces, glue.

Discuss the frequent appearance of holes in your work.

A while back I decided to break away from the very tight and representational work I had been doing in egg tempera and coloured pencil for so many years (see below). I had picked up an old 1905 Underwood typewriter at a flea market, a clunker, but beautiful in some ways for how it looked, no longer for what it did. I made dozens of drawings in almost as many media, from every angle, creating loosely abstracted, experimental interpretations of the machine.

Shiftlock Balloons, 20” x 28” coloured pencil on rag paper

Shiftlock Balloons, 20” x 28” coloured pencil on rag paper

Eventually the round keys emerged as elements that carried forward into my next series: very large collages using found paper and oil stick. The paintings all seem to contain that circle, stretched and pulled, as figure and/or window, singly or in masses. In some paintings they succumb to gravity; in some they repel or attract each other like magnets. What intrigued me was their engagement with each other, and their energy in space. So when I turned to fibre, they appeared again, as holes in the fabric. Hard to explain why certain elements become iconic in one’s work. I think the shape simply pleases me. Perhaps the artist should focus on making the work, and leave the explanations and connections to more objective viewers!

Light into Darkness, 48” x 48” found paper collage, oil stick

(collection of Fed Ex Canada)

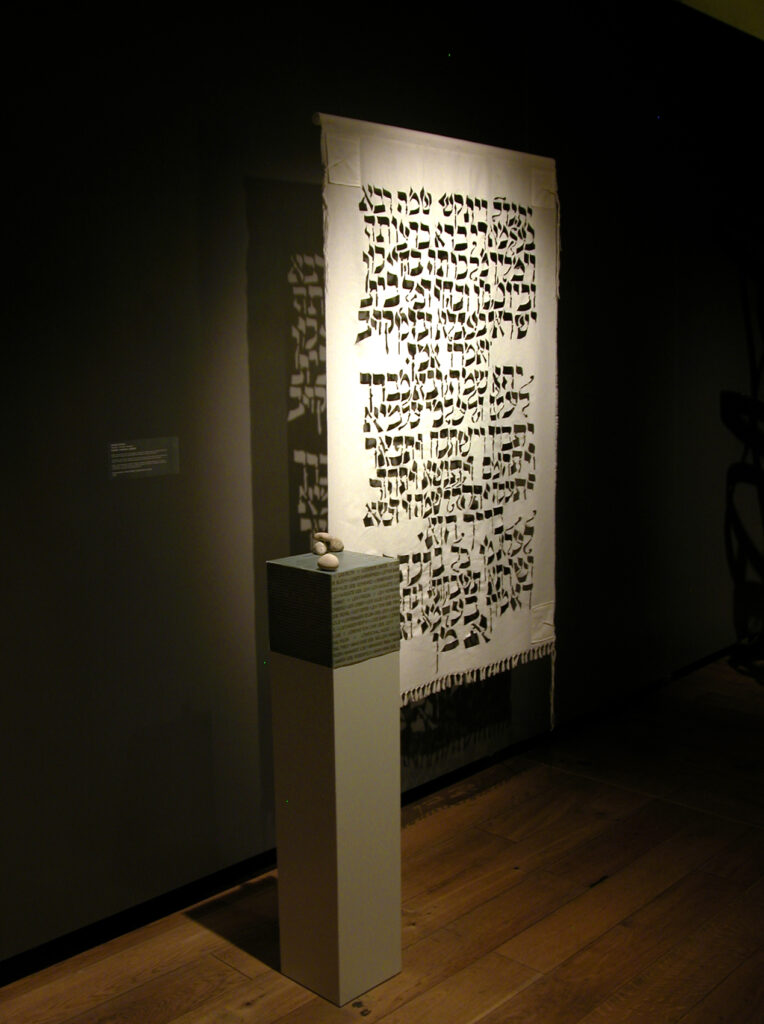

You attended a residency in Latvia. What was that like?

Yes, in 2016, I was chosen to participate in a Textile Symposium in Daugavpils, Latvia, a small town three hours from Riga with the distinction of being the birthplace of Mark Rothko. Some years after his death, Rothko’s two children gave money to turn an old fortress there into the Mark Rothko Art Centre, and since then it has been a gathering place for artists in various disciplines to live and work at the museum, sharing intense time together, culminating with an exhibition of the work done during the residency. I knew little about Latvia before I went, but some research taught me that a once thriving Jewish community there had been decimated, first by the Nazis, then the Soviets. Even on Yom Kippur when I visited there was no service at the one synagogue that survived in town. Under the Soviet regime, even recitation of the mourners’ prayer was forbidden in public. I knew then that I had to make something to pay homage to this cruel history. I ended up with a linen hanging where the Hebrew letters of the Kaddish (mourners’ prayer) were cut out of a handmade prayer shawl. When illuminated from the front, the light was projected through the holes as a ghostly image on the wall behind. Beside it stood a plinth with names of some of the victims (copied from the Holocaust Museum in Riga), the prayer transliterated into Latvian, and a few stones as is the custom to leave at a Jewish gravesite.

Kaddish 60” x 48” linen, fringes (Permanent collection of Mark Rothko Art Centre, Latvia

During the residency I read a memoir written by a survivor of the Daugavpils ghetto (How Dark the Heavens by Sidney Iwens). I came to a paragraph where he describes seeing a huge dark shadow ahead of him as he ran through the forests at night. Approaching, he realizes that it’s an old fortress. And there I was, 65 years later, reading his book in that exact location– the fortress renovated by the Rothko family. Both Iwens and Rothko lived in the US for most of their lives but had never met. I left the memoir for the Rothko library, returning it to from where the story began.

Take one specific Memory Project that actually has a wonderful deep memory for you or the commissioner.

Recently my niece gave birth to her first child, a little girl that she and her husband named Adira. The Hebrew name means “strong woman.” As a gift for the newborn I thought of making a soft little quilt for her, and asked that the squares of fabric I needed be contributed by the strong women in her life– her grandmas and great grandmas, aunts, cousins, and dear friends of her mom. People were truly delighted at the chance to send something. Little by little envelopes arrived in the mail– pieces of fabric embedded with memories from special items of clothing, from old pillowcases, favourite jeans, a treasured tablecloth. Many of the women included a blessing for the baby or a story about where the fabric came from. After they were all collected, I made the quilt and had the new parents take photographs of the baby cuddled up in it, which of course we sent to all of the contributors.

Adira’s Quilt, 40” x 30” varied fabrics, batting

Are any of your works wearable art?

They look as though they could be, but no. Usually I’m deconstructing wearable garments for their parts.

Joomshirt, 30” x 52” x 6” haji paper, buttons

Recently however, I made a new shirt using the ancient Korean paper felting technique called Joomchi. It’s made entirely of Hanji paper, layered and manipulated so the long fibres break down, fuse, and develop holes. As a reversal, I cut up a fabric shirt to use as the pattern for the paper shirt. Each section was kneaded individually with water and, “eager hands,” as Jiyoung Chung, a well-respected teacher of the technique, puts it. I was so delighted when Joomshirt was chosen for Excellence in Fiber 2019.

Discuss your paintings in the series, ‘Scapes of the Clothed Figure and how the human form can influence fabric.

For many years I drew and painted the figure, using coloured pencil, egg tempera, or oil. Because I would leave off the heads, and often the hands of my subjects, I had only their bodies to explain who they were. Relying then on what they wore, the gesture of the pose, and the body type, it fascinated me to see how much of a person can be described.

Madras, 28” x 19” Coloured pencil on rag paper

It was always the clothed figure I found so intriguing for we must conjure the body underneath based solely on the contours and lie of the covering. Parts are hidden under folds or stiff fabric. Other parts are revealed through taut, clinging, or transparent fabric. It’s an exploration. But it’s also a metaphor for any covering over form, any façade which simultaneously can hide and reveal what is underneath. Pushed psychologically, the metaphor can describe our own affective behaviour, as we allow some aspects of our nature to be shown to the world, but conscious or not, keep other parts hidden.

How do you personally see the pandemic affecting the art you are part of?

There has already been a very visible change in the art scene for the same reasons that affect so much else. Exhibitions have closed early, have been pushed ahead months or even years, or are cancelled altogether. Four shows that were to include my work have been postponed. The summer outdoor shows were moved online, a bold change for their organizers and I applaud their flexibility. But it’s hard for most people to buy art they haven’t seen up close, especially fibre art, a difficult sell to begin with and not displayed to advantage on a small screen. Outdoor fairs are a social event and family outing; sales are far less likely when the artist isn’t present to talk about the work.

In a time of uncertainty, art is the first thing we think we can put aside. Who will be spending money on a painting when they aren’t confident about the economy, or fear their job is in jeopardy? Who thinks of adding to the beauty of their home when no one is visiting? Who is gifting art when celebrations are cancelled? Our focus is on getting groceries safely, and deciding if it’s right to send our kids to school. Acquiring art will wait.

Artists aren’t just worried about diminished sales. Many have kids at home and must direct their creative juices toward activities for them. Many artists I’ve spoken with just aren’t feeling inspired. They are scared, or depressed, and if they can’t work they don’t usually qualify for unemployment benefits.

I happen to be one of the lucky ones whose kids are grown, and whose family income hasn’t been affected much. I still spend most days happily ensconced in my home studio. There are fewer distractions. Personally, I have found that making a very large piece (aiming for 8’ x 9’) with many intricate elements is giving me a necessary sense of continuity and direction that I don’t feel elsewhere. The finished piece is only a vague idea in my head, allowing me to change course as I go, experiment, stay light on my feet. And that keeps me challenged. At a time of deadly disease, social and political unrest, far too little contact with my kids and grandkids, my studio has become the only place I can feel I’m in some degree of control.

I Want to Bubble with Everyone, 8’x 9′(in progress) Deconstructed Clothing, discarded swatches from interior designers, sewing, quilting.

I Want to Bubble with Everyone, 8’x 9′(in progress) Deconstructed Clothing, discarded swatches from interior designers, sewing, quilting.

Play this short video, and I promise you will be smiling and feeling, Oh! so much better. Ready to face another day or even the whole week ahead. Thank you Susan for sharing this with us all.

Contact:

Susan Avishai

susan@susanavishai.net

www.susanavishai.com

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September 2020

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: