Stephen M Redpath Painter

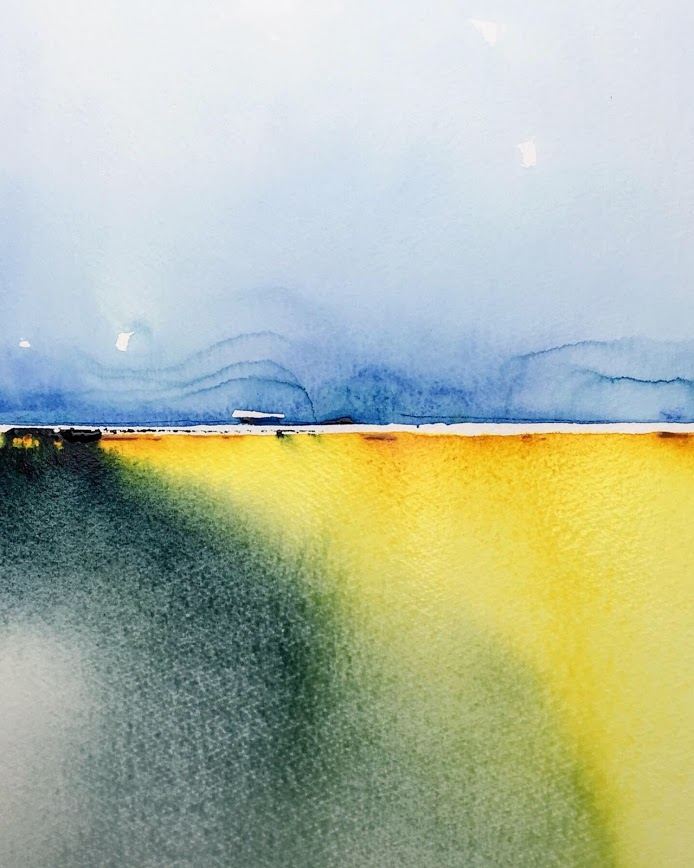

Many of your watercolours are dominated by the horizon – discuss.

The horizon is a mysterious, glorious and untouchable thing and I spend a lot of time staring and thinking about how to represent it in my work. Often, I find that a simple line of paint, representing an horizon, can capture what I’m after and take me to another place. See the two paintings below as examples.

A Distant Shore, Watercolour, 34×15 cm

On a practical level, horizons help set the perspective and I spend a lot of time playing with the position in the paintings and how that changes the feel of the piece. However, not all of my work is focused on horizons. Sometimes I want to escape their tyranny, but I do find myself coming back to them again and again.

Three Trees, Watercolour, 50×20 cm

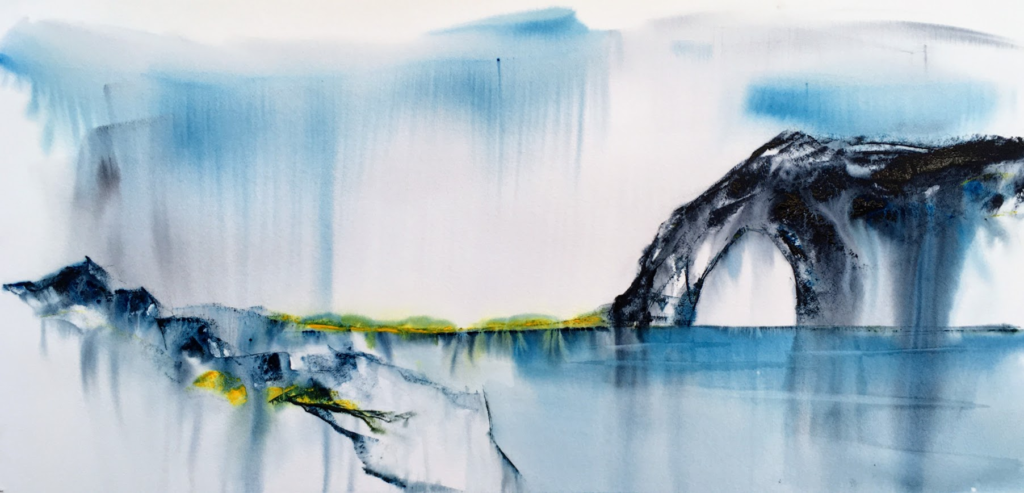

How is your work able to command the word ‘Vast’ so well?

Vast landscapes take your breath away. They give us perspective on our place in the world in the same way that staring into the universe at night does.

Landscape in Blue and Gold, Watercolour, 32×50 cm

I am interested in trying to represent that feeling of awe. How do I do it? Well I find that a tricky question to answer. First, I should say that I have spent a lot of time looking at how other artists, such as Turner or Ackroyd do it and why they are so brilliant at giving a sense of space. For me, I think it comes down to leaving ambiguity and space in the painting and not cluttering up with detail. It is about what you leave out as much as what you put in. I use a lot of large washes and let them bleed gently into white paper.

Sunrise in the Mountains, Watercolour, 38×54 cm

Your landscapes bring climate into the paintings expand on this using ‘Shower Moving Inland’.

Shower Moving Inland, Watercolour, 53×35 cm

Living in Scotland and sketching/painting a lot outside, I naturally find that the Scottish climate and light imbues almost all of my work. Of course, when you live here, you can’t ignore the weather. Indeed weather provides so much of the interest in landscapes – the shifting shadows, tones and colours, the excitement and energy of storms and of course the rain. Wonderful challenges for a painter. I can’t really imagine living in a better part of the world, for the diversity of landscapes and weather, and for the delicious, northern light.

You make the comment ‘I love to work in that area between representation and abstract’ expand on this comment.

As my painting has developed, I find that I’m not so interested in purely representational work or very abstract work, although obviously I greatly admire other artists who work in these ways. When I’m out in the countryside, I often feel a variety of emotions, from awe and elation to anxiety and sometimes even fear. It is that overwhelming, emotional experience that I feel compelled to try to capture in my work. How it feels to stand in these incredible places, that have been crafted by geological forces over millions of years and that are home to unique assemblages of species.

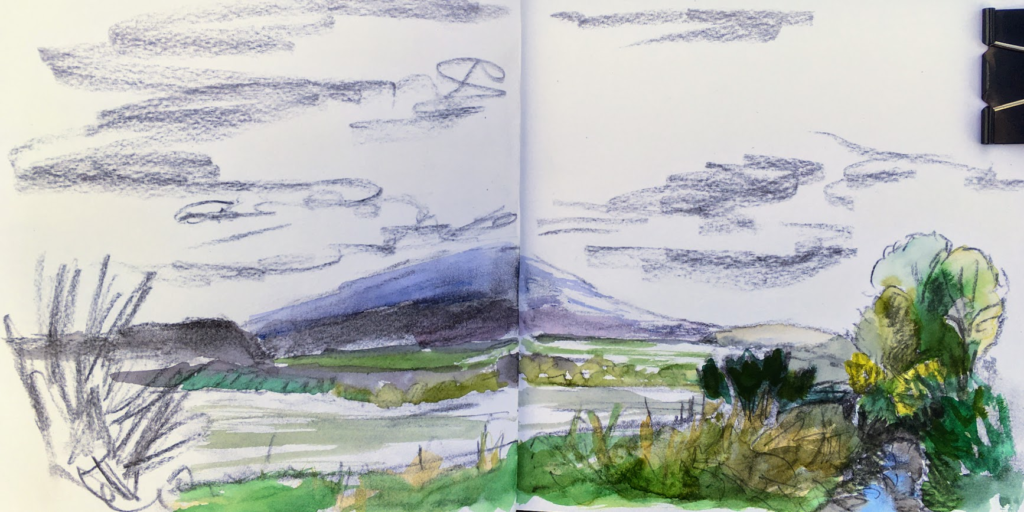

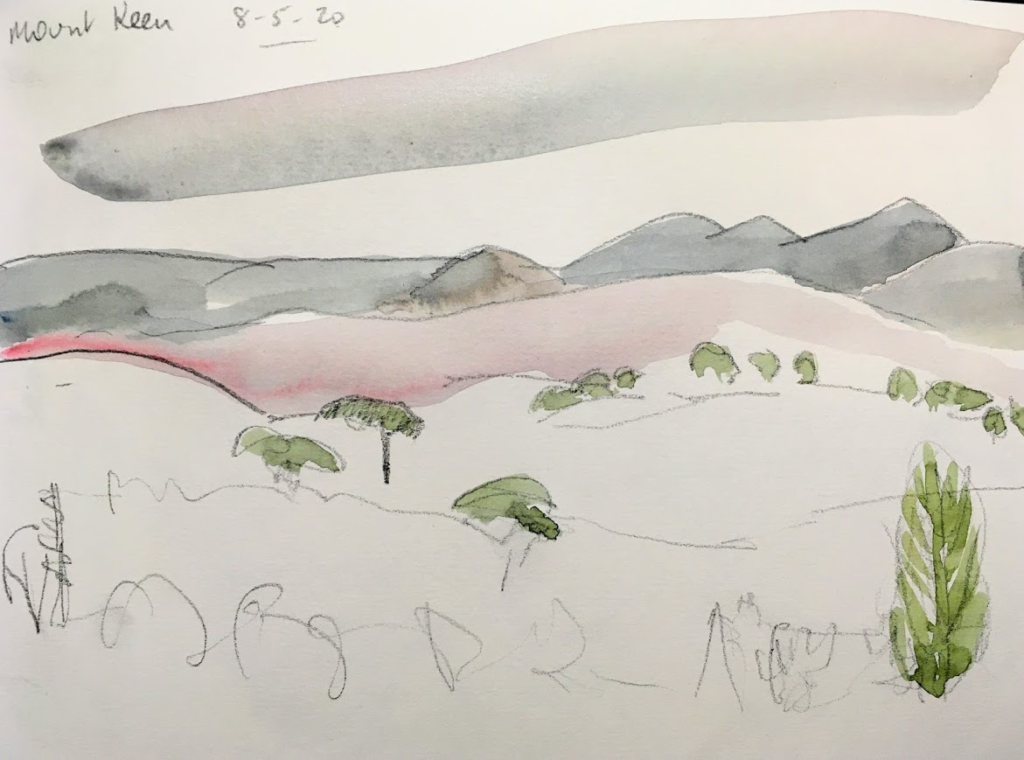

I often start with representation. I do a lot of sketching outside and constantly looking for those little moments or places that are the key to capturing a sense of place. I also take reference photos.

The Howe of Cromar (from sketchbook) Watercolour and charcoal

I come back to my studio, I put the photos and sketches up and quietly I re-imagine myself in that place I want to paint – the feelings, the light, the sounds, the smell and the landscape. Then I work quickly to try and capture that feeling. I don’t care about the details – whether the line of a mountain is exactly right, or a tree is in the right place, or even whether there is a tree – it is about whether I look at the finished work and feel moved and a connection to that place. Sometimes, I skip the whole sketching part and work from the memory of place alone and look inward to find the spirit of a place I remember.

The Howe of Cromar. Watercolour, 20×14 cm

So when the process works it is a conversation between the painting, my emotions and the landscape – I find I disappear completely into the work and pop out at the other end. Boy – that is a wonderful and addictive process. But of course it can also be frustrating when it doesn’t come together as I would like. In that case I keep on trying to figure out why something didn’t work. In fact having a painting that I don’t like gives me such freedom to try approaches I probably wouldn’t try on a blank piece of stretched paper. I am surrounded with folders of discarded paintings…

How has your former University life with wildlife and landscape influenced you painting?

Oh, in so many ways. I spent 35 years working on wildlife and conservation issues, and all of that history and learning and experience has naturally contributed to who I am. We live in a time of brutal and rapid change to our natural world, so I carry a constant sense of grief and anxiety. I can see this coming through in some of my work, and I am sure it will continue to do so. But at the same time I don’t want to focus on the negative, I want to reflect a sense of hope and love. This is partly to help maintain my sanity. Using art as a therapeutic way of dealing with the grief helps for sure. I hope it may even help lift and inspire others. I also use art as a

It is odd moving from a career in science to one in art. I find both approaches incredibly exciting and stimulating. Obviously, there are many differences between the two, but they share three important things. First, they are both focused on finding a truth about the world how it works and how it is experienced, second, at their heart they stem from careful observation, and third, they both rely on reflection and criticism. So in these ways my science life has made my entry into the artistic world easier. I have spent much of my life working in UK upland landscapes, and I have also been fortunate enough to travel to amazing places around the world for work. My head is full of imagery from these places and I know these inform much of my work.

To be a Buzzard & create a sky. (from poem by Norman MacCaig] Watercolour, 50×78 cm

Discuss the boundaries you see in the landscape and your current work.

I am always aware of the boundaries that affect my relationship and connectedness to landscapes. I was incredibly lucky to spend some time in the Serengeti a few years ago. It was amazing to see the wildlife and the big open spaces, but in these situations, there was no feeling of belonging, of being a part of the place. As we drove around in our Land Rovers, it felt as though I was watching it on television, rather than actually being a part of it. This deeper connectedness only comes when I spend time walking, snoozing, getting wet, sketching etc. Where I live in Aberdeenshire I walk almost every day in the amazing countryside around our village, and my relationship with it has totally changed over time. It feels a part of me. This barrier between the artist and the landscape is something interesting to explore. I am uncertain how it affects my work, but I feel sure it does.

The view from the village, Watercolour, 46x31cm

The land where I live (from sketchbook) Watercolour, 20×14 cm

My awareness of boundaries has been exacerbated by having Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), which I was diagnosed with last year. For those who don’t know about CFS, or M.E., it is grim. It sucks the energy out of you and affects your cognitive function, leaving you exhausted, confused and disorientated. Not surprisingly, this condition has affected the relationship I have with the world. It seems further away, as though I am trapped behind glass. I battle with this daily and sometimes the frustration pours out of me when I’m painting – see the two paintings below.

A Lost Connection, Watercolour and charcoal, 48×68 cm

You have recently been diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. What has the silver lining been for you?

I am so lucky that my condition is better than other sufferers have to live with. The glowing, silver lining is, of course, that I am able to paint. I often struggle to read and write and be coherent (writing responses to these questions really takes it out of me), but thankfully the condition doesn’t hinder my ability to paint, often for hours on end. What an absolute, glorious joy.

The pandemic has been hard on artists and galleries. Can you tell how you have dealt with 2020 so far?

It has been a roller coaster. My world came crashing down last summer, when I got diagnosed with CFS, so I went into my own personal lockdown as a result. My life hasn’t changed all that much since.

The Wildness Within, Watercolour, ink & charcoal, 72x54cm

I spend all day, almost every day painting, exploring and playing. In fact, despite the illness I feel incredibly fortunate – like a child in the largest sweet shop in the world, without the risk of diabetes or tooth decay. One frustration with the whole pandemic business has been that I’ve had my first two exhibitions cancelled. Fortunately, however, I have finally been able to show my work this autumn at the Tolquhon Gallery near Aberdeen, so I’ve been able to see what they look like together up on the wall in space.

The size and shape of your paper reflects the different landscapes discuss this use three different sizes.

Stillness, Watercolour, 120×80 cm

I have been playing with a variety of different papers that vary in size and texture. Size and orientation obviously affects the feel of a landscape. Recently, I have started to paint on larger paper and it is such a thrill. It forces you to work at a different pace and is dynamic and energetic and stimulating. It also helps create that feeling of space.

Arctic peace, Watercolour, 120×55 cm

You are not afraid to use dramatic colour combinations in your work neither is nature, discuss.

I adore colour and playing with combinations. Why be afraid? When you go into landscapes and you sit and really look, you see amazing colours and dramatic combinations. A lot of my watercolour work builds on calm and subtle colours, but nothing is more exciting than a line of bold colour in an otherwise calm painting.

Incoming Tide, Watercolour and ink, 72×46 cm

I really love and admire the work of Brian Rutenberg and I sit and stare at his use of colour. Sometimes when I want a break from watercolour I will work with pastels or acrylics, to be able to enjoy rich colour.

Tarland Burn, Oil pastels, 15×15 cm

We are often told ‘Less is best’, you achieve this in your work. How can you convey so much with so little?

This is at the core of what I do. I am driven towards simplicity and I am slowly learning to achieve it through experience. The challenge of course is understanding when to stop. This takes time to learn (at least for me), so sometimes I force myself to not stop but carry on adding to a painting, generally until it is a hopeless mess. The key thing here is to watch myself and reflect on when I felt the most power in the painting and when it flipped to a different state. In watercolour it is that first line that is often so important – like the surgeon making the first cut. You have to be bold and confident. In the painting below I knew I had what I was trying to achieve after the first mark.

The Coll, Watercolour, 78x54cm

Where did you learn the art of watercolour?

I am still learning. I haven’t been to art school and have only done a few evening classes, so I try and study other artists such as Turner (obviously), Ackroyd, Marin & Melville and I paint, paint and paint, with a self-critical eye. Slowly I am getting to know other artists to get their feedback and to understand their practice. And this winter I am doing a 5 month residential art course with a highly regarded art school (Bridge House Art in Ullapool). I want to be challenged and to learn and then bring that back into my work.

Pike Lake, Watercolour, 38×28 cm

Since my career in science stopped! I have finally allowed that compulsion to paint to come out. It feels like opening the floodgates and there is no way I could possibly stop now. I paint constantly and I’m just completely captivated by watercolour and trying to figure out how water and pigment and paper interact. It is just so exciting. Sometime maddening, but often it makes me gasp with joy – how that first line of Prussian blue demands attention or how a wash slips and settles and competes with its neighbouring colours. I do paint with pastels and acrylics, but watercolour is my first love.

Why is it so important for you to share your landscape through art?

Firstly, painting landscapes is a compulsion. I don’t seem to have much choice in it and my main motivation does not come from wanting to share. I get up in the morning and I simply have to paint. I often dream of colour and landscape and I need to get it down. That said, it is a pleasure and a privilege when others are moved by my work. Naturally, I hope that by producing work that moves me, it may also move others, bring some light and just make this world a tiny bit better.

Contact:

Stephen M Redpath

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September 2020

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: