Rogan Brown Paper Artist - Languedoc, France

Expand on your comment, “Walking a narrow and sometimes contentious line between fact and fiction, observation and imagination”

When I say that my work is inspired by science it raises certain expectations particularly in relation to the question of accuracy; in simple terms how factually accurate are the sculptures I make? In reality, that question is far from simple because what I depict in my work are subjects that are mostly invisible to the naked eye and that can only be glimpsed through electron microscope images or alternatively through technical diagrammatic representations. Both these forms of representation are accurate to a point but are also misleading: a cross sectional diagram of a cell for example simplifies and schematises what it represents, and electron microscope images often use coloured filters which distort the reality of what is being depicted. I make use of the aesthetics of both diagrams and micrographs in, my work but they are only a starting point; as each piece progresses it is transformed through the creative process and embellished by the imagination because what I’m seeking to convey is a poetic essence and truth rather than a factual one. The difference between a fine artist and a professional scientific illustrator. It is the difference between understanding a landscape by looking at a map and understanding it by looking at a painting by say Monet; both are schematised representations, but one seeks to convey factual truth, the other a poetic, emotive truth. In my work I try to find a bridge between these two approaches.

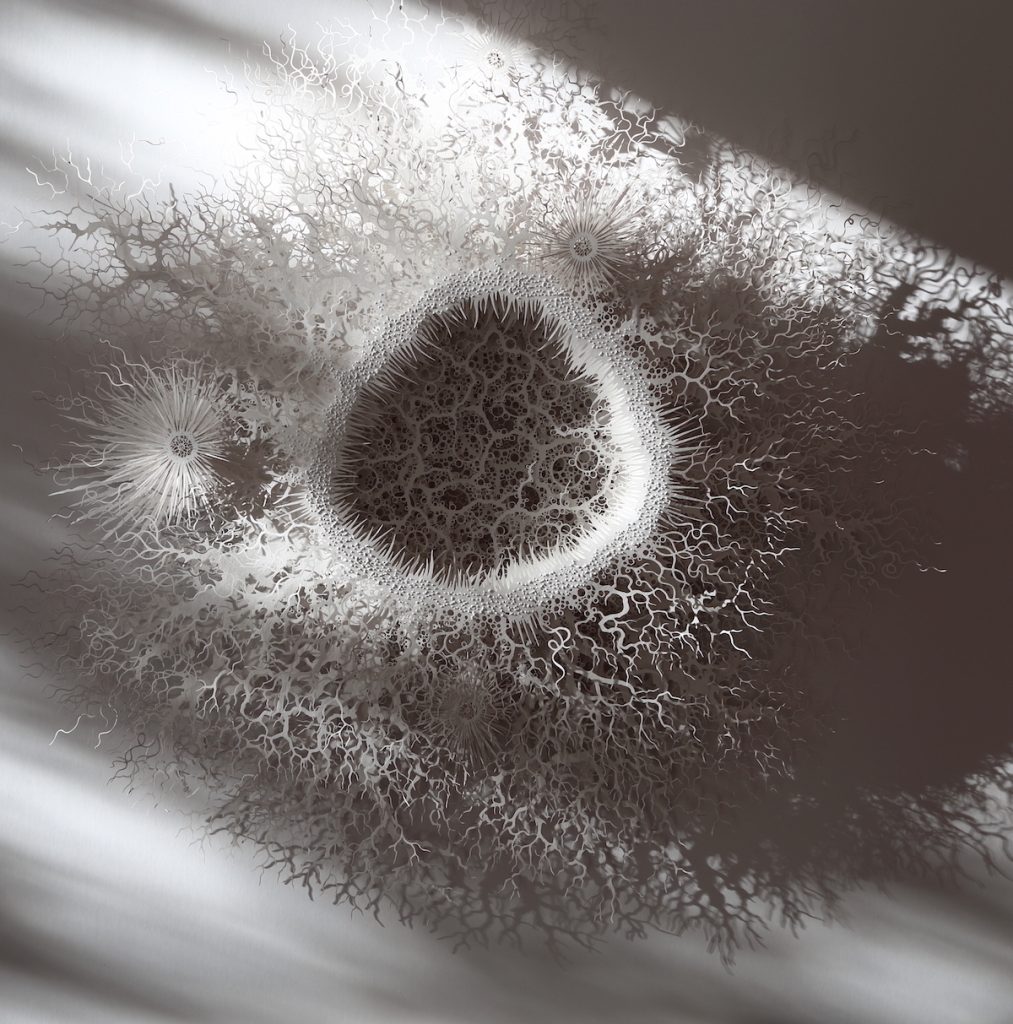

Reef Cell, 83 x 83 cm, Laser cut paper

The humble chestnut husks have been very influential in your work, discuss.

Kernel, detail

I lived in a chestnut forest for 10 years and became fascinated by the strange surreal beauty of the tree’s fruit: the sharp spikes of the husk, painful to touch, protecting the shiny mahogany fruit inside; such a stunning contrast of form and texture. This dynamic interplay between interior and exterior is seen throughout nature where skins or shells contrast with what they cover and protect. We see it in anatomical drawings of the human body, (another great source of inspiration) where the smooth skin is pulled aside to reveal the formal complexity of the organs and branching arterial systems that it covers. Likewise, the structure of the spiky orb of the chestnut can be seen repeated in other contexts, for example, on the microbiological level, in the shape and form of certain viruses. It’s these structural echoes, parallels and patterns that fascinate me in nature and I constantly research them, trawling through satellite images of the earth and telescope images of the planets, microscopic images of bacteria and pathogens, electron micrograph images of cell structures, anatomical drawings, as well as pictures of birds, insects, reptiles, fish, crustacea, mammals…constantly searching for shapes, patterns and structures that are repeated at different scales and in different contexts: symmetry, fractals, branches, bubbles, waves, spirals…. These are the aesthetic building blocks of life, the architecture of the natural world and I use them to create hybrid sculptures, chimeras that make multiple visual references simultaneously.

Kernel, 137 x 107 cm, Hand cut paper

Can you briefly explain the process and technique of your work?

Every piece starts with drawing, the finished work is really a layered three dimensional drawing. I start with small sketches then work these up into detailed full scale drawings that are then cut either by hand with a scalpel (eg “Cut Microbe” and “Outbreak”) or alternatively with a laser (eg Magic Circle Variation). Each cut is then mounted on hidden card and foam board spacers of 1 or 2 cms depth and finally each layer is mounted on top of the other, glued and pinned in place. The process is therefore long and labour intensive especially for the larger hand cut works that can take several months to produce.

You call your work sculpture rather than 2D work discuss this in relations to your work.

The pieces are in fact base relief sculptures that can be anywhere between 7 and 20cms deep. Although paper is the principal medium the essential element is light and by making them monochrome I maximise the interplay of light and shadow. The photos you see freeze the works at a specific moment with a particular lighting set up but in reality they change and move according to the changes in ambient lighting.

For me sculpture creates a more powerful, direct visual experience than 2D work because it is not the representation of an object, it is the object itself and asserts its own autonomy.

Outbreak, 147 x 79 x 20 cm, Hand cut paper

You have worked with scientists explain how this came about and one or two connections that have strongly influenced your art career?

I was invited to collaborate with a group of microbiologists who were in the process of working on a Wellcome Trust funded permanent exhibition focusing on the Human Microbiome, that is the vast colony of bacteria that live in and on our bodies and that scientists are only beginning to understand thanks in part to inexpensive DNA analysis. I was one of a group of artists asked to make work inspired by bacteria. I think the experience made me realise how large the culture gap is between the two disciplines; there is a sense that science is dealing with the hard edge of reality, with results changing and improving our lives in very practical, measurable ways, whereas art is really a little bit of entertainment, embellishing our lives but not fundamentally altering it. At a certain level this is not easy to argue against, art does not make planes fly or cure infectious diseases and its contribution to our lives is impossible to measure, but for me it is an equally valid reflection on the nature of the world we live in, teaching us to see the world in new ways or to see familiar things in a fresh light so that we become aware of the act of looking and seeing. As such the arts are just as crucial as science in helping us explore the meaning and purpose of our lives and in helping us maximise the experience of being alive.

In relations to science expand on how you use ‘Escherichia’ coli and enlarge this single bacterium into a large paper sculpture?

The exhibition that this sculpture is part of is called “Invisible You” (www.edenproject.com/visit/whats-here/invisible-you-the-human-microbiome-exhibition) and all the artists who contributed to it try in different ways to help us conceptualise and see in a new way something that is crucial to our existence and our health but which we most often regard in a very negative way, namely bacteria. Humans are symbiant beings, that is to say we live thanks to a mutually beneficial relationship with an unimaginably vast colony of bacteria that helps us in myriad ways, such as breaking down food in our gut and extracting all the good nutrients from it. Taken as a whole bacteria is not only good for us, it is essential to our survival but occasionally it can harm and even kill us, and it is these latter aspects that sadly tend to dominate public consciousness.

The object of the exhibition was therefore to educate the public about the benefits of bacteria and to try to change public perception. My personal aim was to try to make the words “beautiful” and “bacteria” associate in the mind of the viewer, so I set out to create a sculpture of a single bacterium that looked as beautiful as possible. I chose ecoli because it is more aesthetically interesting than other bacterial forms as it is covered long hair-like appendages called flagella that allow it to swim through our bodies and I knew I could use these to create a sense of movement and rhythm that would maximise its visual impact. Ecoli is also well known to the public as a bacteria that causes illness and I wanted to use that negative connotation to create a contrast with the beauty and elegance of the representation that I hoped to create.

Cut Microbe 2, 112 x 90 x 20 cm

Discuss the size of your work and the restrictions you have with size due to paper?

Paper’s obvious fragility means that the sculptures need to be placed under glass or perspex in order to protect them. All the pieces are framed in bespoke deep rebate box frames under glass which are heavy and consequently difficult to transport so this limits the scale at which I can work. The largest pieces I’ve created are 150x150cms. Scale is a crucial aspect of my work. I’m drawn to subjects that defy our limited human capacity to imagine scale, for example bacteria which individually are unimaginably small but which, in terms of number, are unimaginably vast.The same is true of the neurons in the human brain, a subject I’m exploring at the moment. I try to reflect this contrast of scales by taking a very small subject such as a bacterium or cell, expanding it in size and then rendering it in minute detail.

Light must be a huge problem – how do you get this just right in your studio?

I live and work in the south of France which is very light all year round and my studio is flooded with light.

In other works of mine, the goal was to alter viewers negative perception of bacteria” discuss.

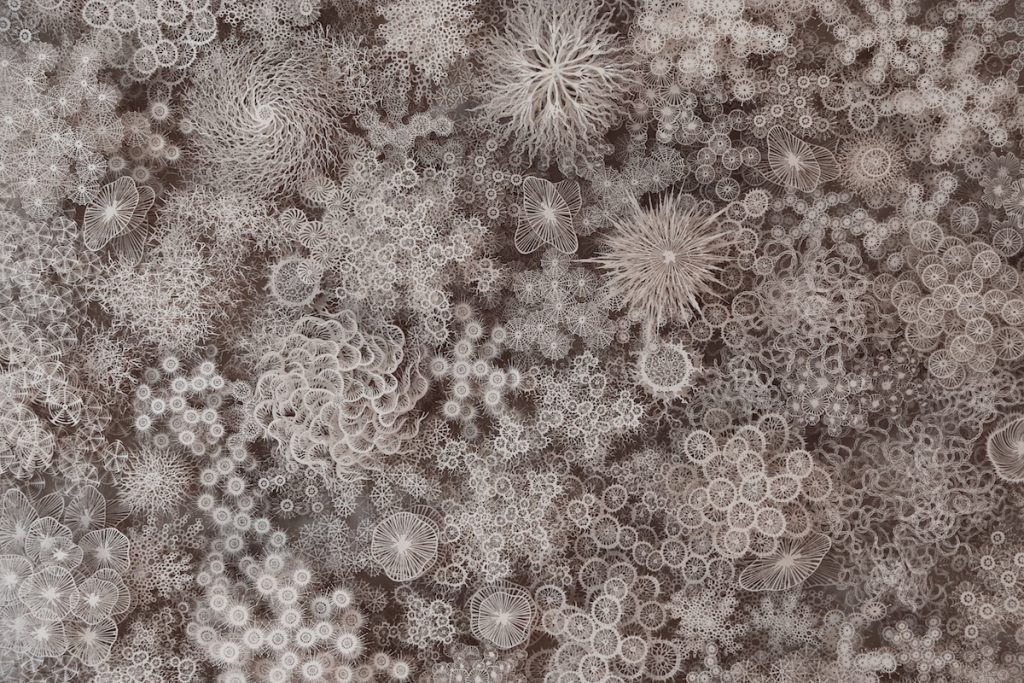

Magic Circle Variation, detail

In the “Magic Circle Variation” series I continue to play with the aesthetics of the bacterial world but here I try to create a visual representation of a bacterial colony. Diverse forms are arranged together in a circular composition that refers to the shape of the petri dish and also to Buddhist mandalas, those intricate sacred images that represent the harmony of the universe. The bacterial colonies that inhabit us are also diverse but work in unison to keep us functioning and create harmony in our bodies. “Magic Circle” is an attempt to communicate that sense of diversity and harmony.

Magic Circle

Give your personal thoughts on collaboration between scientists and artists?

I think such collaborations are crucial; we live in a world dominated by science and technology but sometimes as non-scientists we can feel marginalised, ill-informed and excluded. Artists can play an important role in engaging with science and making it accessible to a non-scientific audience, not in terms of explaining the mechanics of the science but rather by giving a personal, individual response to what is often such a large scale collective endeavour. Art can therefore build a bridge between science and the general public. There are some very exciting but also slightly terrifying developments taking place in science which need to be discussed and debated by the whole of society and not just the scientific community. I’m thinking principally of the development and implications of something like Crispr technology which allows us to alter DNA cheaply and easily for the first time. The ethical issues raised here are enormous but there is little or no public debate about how we should employ such technology. Chinese scientists are already conducting human tests but may be opening a Pandora’s Box as they do so…

At the same time I disagree with the notion that the only role left for art to play in society is as a vehicle for exploring socio-political issues. I still believe in the pursuit of beauty as a key driving force in art; but we must look to other branches of knowledge and research in order to find new ways of achieving and expressing that beauty.

Cut Microbe, detail

Contact details:

Rogan Brown

http://roganbrown.com

Rogan Brown, Languedoc, France

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May 2018

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: