Richard McVetis Textile Artist

Do you feel that coming to embroidery without any preconceived knowledge has been a great asset to your work?

I had a very basic view of textiles and embroidery before art school. My auntie would visit on Monday evening and knit our Christmas jumpers, and I had a little bit of experience with cross-stitch from school. My introduction to embroidery was a happy accident and, in fact, happened on a visit to the open day of the Embroidery degree at Manchester Metropolitan University (which sadly no longer exists as its original entity). The course opened my mind to the broad sense of the word ‘embroidery’. What attracted me to this place was the chance to learn one of the world’s oldest crafts whilst exploiting the contemporary possibilities of this medium at the same time; without a doubt, this period of my life is one that I regard with great fondness. The diversity and exploration of the medium are liberating. Under excellent tutelage, we were encouraged to use anything and everything as materials in our work. As a result, there was always a sense of everything being well made and always well thought out, whether design or fine art.

Can you discuss why embroidery is not grouped with ‘art’ rather ‘craft’ so often.

For me, the intersection of art and craft was the most exciting and provided constant inspiration. I like embroideries somewhat conflicting status of being fine art and craft, depending on where and how it is presented. Ultimately though, its association with the domestic or women’s work has held back embroidery and textile art, and this is due to the patriarchy and the art world hierarchy. This perception has somewhat shifted over the last fifteen years, for example, recent exhibitions of artists such a Jessica Rankin at White Cube, Sophie Taeuber-Arp at Tate Modern. The difference, of course, is the route in which these artists take. Artists studying fine art and working with textiles are more excepted within the fine art world than artists who study textiles.

Discuss your work in relationship to repetition – “A moment in time.”

My practice is deeply rooted in process and hand embroidery., multiples of dots, lines, and crosses, all meticulously stitched, record time and map space. My work is about labour, refinement and investing time in very ordinary materials. I explore subtle differences that emerge through the insistent, repeated, ritualistic, and habitual making and giving material form to abstract ideas, making the intangible tangible. Time is a theme that I have explored extensively within my practice.

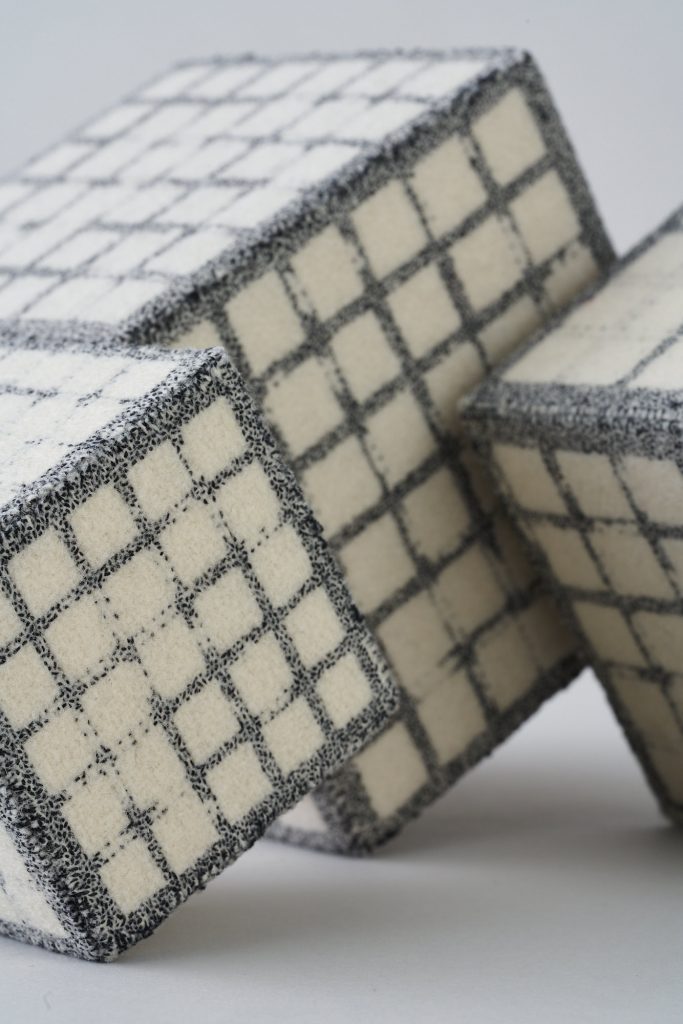

Grid, 2019, 10 x10x10cm, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

I am greatly inspired by the thinking of Carlo Rovelli, in his book ‘The Order of Time’ – he points out that there are not just two times, Times are legion: a different one for every point in space; there is not a single time; there is a vast multitude of them.’

This statement tells us that our perception is unique and relative to each of us. Our time does not extend throughout the universe. It is like a bubble around us, and it is an expanded presence.

‘Units of Time’ became a way for me to try and make sense of this; each stitch is like a comma or a full stop, signifier time, a pause, an interval, a mantra.

Grid Collective, detail, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

Rooted in this tradition of hand stitch, each of these objects becomes a very individual expression of my time. They demonstrate my need to engage with and connect to the world through touch.

Creating objects also helped me subdivide extended periods and represented moments of my time, translating the intangible into something tangible, tactile, something you move around and draw within space. They record and persevere fleeting moments, found patterns, the objects become markers of time, an embodiment of this deep focus and patience.

Grid Collective, detail, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

These works extend from me, the past condensed into physical form and infinitely rearrangeable. “A moment in time.”

Do you think this has been heightened by lockdowns and the concerns for the future?

I feel the pandemic has heightened our awareness of time. There have been moments when time has crept forward slowly and other moments that have sped by. Emotion and stress affect our sense of time, which has been supercharged over the past year. The first lockdown acted as one big brake on a global scale; that sense of everyone experiencing the exact moment is powerful. In a world obsessed with speed, these moments happen rarely. There are few times in our lives when ordinary time has paused, the 9/11 attacks being an example of this; Covid is the next. In Jay Griffiths book Pip Pip, she uses the model of Princess Diana’s death ‘All radio stations and TV channels, all newspapers and all conversations were for once in sync’. She goes on to say, ‘The ordinary time of usual life met the extraordinary time of myth. Mythic time interrupts the succession of ordinary time and the mythic moment is where the profane present meets a sacred eternity.’

Units of time, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

Units of time, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

The very act of slowing down forces us to take notice; we see more. The artist Georgia O’keefe wrote, “It takes time to see”. We enable this by slowing down, which is why I enjoy the slowness of hand embroidery. Through the action of the hand, I attempt to find order, quietness, a rhythm, a very human rhythm that allows you me slow down.

This slowness allows for a more excellent perception of that moment, and it teaches patience, focus.

I’m an anxious person and, at times, too sensitive. I’m hopeful for the future, but I sometimes find it hard to disconnect from the constant news cycle. Creating art is my way of coping and processing all this trauma.

Units of time, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery, detail

Can you discuss your work using the cube?

Two Cubes, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

The exploration of the cube – it’s geometry, intrinsic nature, and perception as both a complex and playful shape – has been greatly inspiring to me. Each cube is individual but is also part of a greater whole, it’s repetitive but varied with my obsessive mark making.

But cube also is a reference to the grid. The Grid format gives the impression of uniformity but also of infinity, an idea discussed in Rosalind Krauss’ Essay ‘Grids’ she also goes on to say, ‘by virtue of the grid, the given work of art is presented as a mere fragment, a tiny piece arbitrarily cropped from an infinitely large fabric’ and the grid to order reality’

This grid and cube offer more rational way to organise the chaos of nature. I also wanted to work to reflect architecture, the way in fact our lives are built and housed in this construct of time.

Three Cubes, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

What made you decide not to work from home but to have a studio outside your home?

For many years I worked at home, it was not financially viable to have a studio. I live in London, where space is at a premium, so it’s challenging unless you have a lot of money and a big house. But I did think it was essential to create some separation; having a studio outside of the home also sets a boundary between home and work life, and as an artist, it’s hard to switch off. I also felt restricted by the space at home. The practicality of space limited the scale and ambition of my ideas.

Variations of a Stitch, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

An essential part of setting up a studio outside of the home was the chance to be part of a community. I have a studio at Cockpit Arts in Holborn, Central London. Cockpit Arts is home to over 140 independent creative businesses. We have public showcases and business incubation services, and they provide makers and materials-based artists with the tools to succeed. Being an artist can be lonely and very insular; therefore, it’s vital to have conversations and support fellow artists who understand what you might be going through.

Variations of a Stitch, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

Have you always shared your work through classes?

My practice informs my teaching, and teaching informs my practice. Therefore, I always include and share my work through classes. I think this is my point of difference and one the main reason people attend my workshops.

Comment on you online workshops, and the variety of students that this format has introduced to you.

Teaching online has meant that there were no restrictions on location, and the accessibly of embroidery allows me to connect to people worldwide. It’s a universal language. People of all abilities and ages attend my workshop. The only difficulty has been attracting men.

Some may not know about the 62 Group, please expand on your introduction and involvement with the group?

Light Abstraction, Tokyo Bay, 50x50cm, Detail

The 62 Group is an artist-led organisation. We aim to incorporate and challenge the boundaries of textile practice through an ambitious and innovative annual programe of exhibitions. Since its establishment in 1962, some of the most highly regarded British textile artists have been members of the 62 Group. As a result, the 62 Group has an established international reputation for professionalism, quality of work and strength of purpose. Member’s work is subject to appraisal by a panel of their fellow members before it is accepted in any 62 Group exhibitions. In this way, we aim to maintain standards and rigour and keep the group evolving.

I have been a member since 2015, and I’m currently the exhibitions officer. My job is to work with the committee to plan an annual exhibitions programe—our next exhibition, ‘Connected Cloth’ part of the British Textile Biennial.

What are you currently working on?

I’ve just finished a new body of work for the British Textile Biennial. The theme of this year’s events focuses on the global context of textiles, textile production, and the relationships it creates historically and now.

I have created two works for this exhibition, ‘Coal seams’ and ‘A Portrait of Coal.’

Using the intensive labour-process of hand embroidery, ‘Coals Seams’ maps and bring to the surface the underground and hidden landscapes of this elemental material formed over three hundred million years ago. It examines my family connection to material, place, class and race; and how, like the seams that shape a garment, Coal continues to shape our lives.

A series of coal portraits highlights the aesthetic, cultural and climate impact of coal. Coal was more than just a material, but a symbol of power, class, and time. The unlocking of this geological time gave us the power to go fast. In Britain, it is a symbol of the past. Ultimately though, Coal is a symbol of the present, the future, and the climate emergency.

Discuss the differences in your 3D and 2D work.

Drawing as an act is occurs in everything that I create. Drawing as a dialogue, a focus that goes beyond the flat surface and into the space around. The objects and structures compose and draw in space, with each architectural setting creating a new relationship. Things must and do exist in dialogue with a scale around it, with the infinity of it all. The only difference is perception and experience; creating is the same.

Phase 1, 100 x10cm, Wool and Cotton, hand embroidery

Contact details:

Richard McVetis

instagram @richardmcvetis

Richard McVetis, London, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October 2021

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: