Peter Randall-Page Sculptor - London, England

You grew up in the country. Do you think, if you had been a city boy, your work would have been different?

Very much so, I was quite a solitary child and spent my days exploring the countryside, collecting natural objects and being rather self-contained. This fascination at looking at the world around me and my place within it has informed my artistic practice ever since.

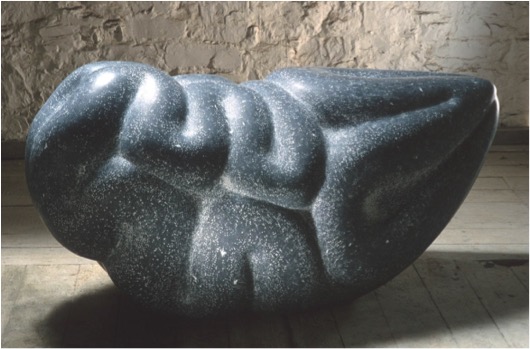

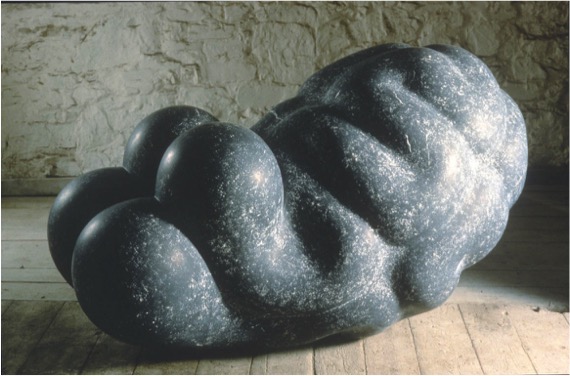

‘ Beneath the Skin, 1991, Kilkenny limestone ‘

photo credit: Chris Chapman

Can you expand on the way you have used continuous coils to create works?

When one looks at a coiled object it conveys the potential to become something more: what happens when it unravels, uncoils, unsprings? The idea of conveying that latent dynamic tension within a material as dense as stone appealed to me, what might be below the surface? What is being concealed? I hope to engage the viewer in a dialogue of what might be beneath.

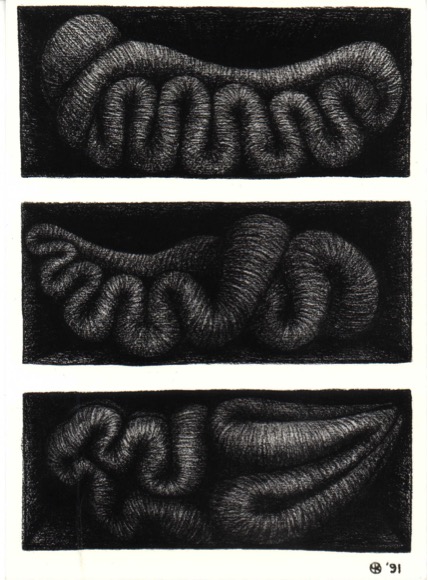

‘Three Dormant Objects, 1991, charcoal on paper’

Can you discuss how you run a parallel between your drawings and your sculptures?

Drawing has always been an important part of my practice as a sculptor.

I always carry a sketchbook and use drawing in many different ways:- objective drawing as an aid to memory and analysis, drawings for sculpture, technical drawings to help explain my ideas to architects, engineers and clients, and other drawings which are not preparatory to anything but works in their own right.

Some ideas reappear over the years in countless sketchbooks before becoming sculptures and conversely, sometimes I have a frenzy of drawing activity for the pure delight of mark making, such as the recent ink flow series. Both approaches are vital to my work.

‘Ink Flow series, ink on paper, 2013

photo credit: Steve White’

Can you expand on geometry and pattern in your work?

Initially, some of my sculptures were quite literal interpretations of natural objects but in recent years my work has been preoccupied with the underlying principals of growth and pattern formation in natural phenomena: exploring pattern and form, order and randomness, geometry and morphology.

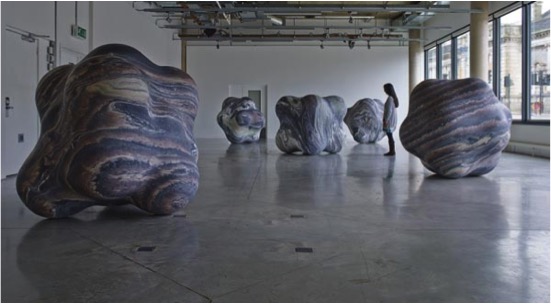

Shapes in the Clouds, 2014 Rosso Luana marble

photo credit: Steve White

You have had three had Individual exhibitions in 2014: London, Devon and Plymouth. We all have 24 hours in a day. How are you able to achieve SO much?

I did have a rather exciting 18 months! What was lovely for me was that each show had a very different feel and dictated a different focus. Due to floor loading restrictions, there aren’t many galleries which can show large heavy sculptures and so it was a fantastic opportunity for me to exhibit at Peninsula Arts, Plymouth, to be able to produce a new body of work without worry of constraint. The exhibition at the Thelma Hulbert Gallery, on the other hand, couldn’t have been more opposite, a domestic and intimate space, it was all about works on a small scale for which I produced a new body of prints. Then the Pangolin show was different again, working with Pangolin Editions.

I spent several days playing at the foundry and they converted these musings into the Inside Out series. Of course, it would be impossible to make all these works single-handed and as well as the technical brilliance of the foundry I also have the support of a very good team here at the studio.

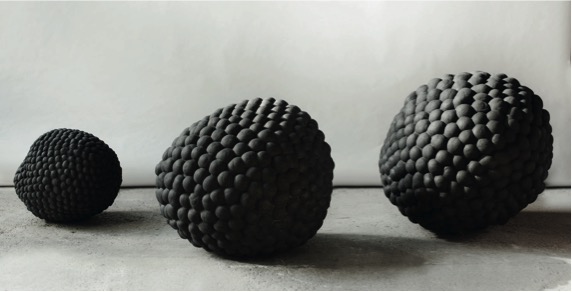

‘Inside Out 2014 bronze’

photo credit: Steve Russell

‘Natural Order’ at Purdy Hicks Gallery in London was a group show with seven artists. How did you collaborate, or was this done by the gallery?

I have exhibited with Purdy Hicks Gallery both as a solo artist and in group shows for a number of years, they approached me with the idea of Natural Order and it appealed to me.

Did you know all of the other 6 artists before the exhibition?

Yes indeed, which is why I had no hesitation in agreeing to the exhibition.

What are your criteria for a Group exhibition?

I think there has to be some cohesive whole created that makes the exhibition more than the sum of the parts.

Can you discuss your thoughts on the value of working in group exhibitions?

I think when group shows work well there is a spark created which adds a frisson to the whole: allowing space for the unexpected to happen.

Your work is in many Public Collections, can you take one that you remember as giving you a huge boost to your career?

Honestly, I am still delighted every time a work of mine is entering a public collection but without question, the biggest boost was when the Tate bought Where the Bee Sucks.

‘Where the Bee Sucks’, 1991 Kikenny limestone

Discuss the importance of Public Art:

– In relation to the surrounding it will be placed in?

‘Give and Take’, 2006 granite and associated hard landscaping

For me, public art is at its most successful when it is integrated into its environment rather than being an ‘add on’: sometimes a development can be near completion before the public art element is addressed. With the commission I undertook for Silverlink Properties in Newcastle I was involved from the initial stages, working with Southern Green landscape designers, to problem solve the different ground heights, need for seating and creating a calm, intimate environment within a busy urban square. I feel we achieved something that wouldn’t have been possible if I’d been called in later in the day: this sculpture went on to win the Marsh Award for Public Sculpture.

– The visual impact it will add to the space?

Often, specifically with urban developments, so many considerations such as parking, transportation, access, utilities and emergency procedures have to be addressed that a sense of human scale and interaction can be lost. Public art can transform an environment, creating a focus and allowing the viewer to indulge in a moment of reflection.

How the sculpture will cope with the weather conditions?

This will naturally vary according to the artist and the artwork: with my granite works I can imagine an archaeologist of the future uncovering a destroyed city and my sculptures will be more or less exactly as they were when they were installed!

– How the sculpture will cope with the public?

My sculptures cope well with public handling: though ‘Seed’ at the Eden Project is beginning to be polished at around 1.5 meters high as the hands of visitors caress the bumps, adding an unexpected but rather lovely aspect to the work.

In Mind of Monk, 2008 marble

Can you give your thoughts on the importance of large Sculpture Parks, like the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, in the life of a sculpture?

Several of my sculptures are made to commission and go directly from the studio to their final home. Showing works such as In Mind of Monk at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park allows these pieces to be seen by thousands instead of a few.

Contact Details:

Website:www.peterrandall-page.com

Email: contact@peterrandall-page.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Peter-Randall-Page/46843490580

Peter Randall-Page, London, England

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, January 2015

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: