Nick Hollo Pastel Artist - Sydney, Australia

You are not only interested in location but the vegetation and land surface, expand on this and your work North Head Triassic Formation?

North Head Triassic Formation, Pastel,84 x 59cm

We all think our environment is beautiful but there is very little understanding of the forces that have shaped it. Without articulating the special qualities of our surroundings, we are unable to protect it nor to encourage the right measures to improve it. I started to make pictures that try to express the underlying forces that have shaped the land and the life it supports.

One can’t really know Sydney and its harbour without understanding its geology. In North Head Triassic Formation, which is part of The North Head Project exhibition at the Manly Art Gallery and Museum until 18 February 2018, I am trying to express the significance of the geology that makes Sydney what it is. The picture depicts the ancient layers of sandstone exposed on the cliff face. What look like the erosion patterns on the cliffs are contrived to show life forms that existed in the Triassic period 220 million years ago when a vast river delta laid down the sediments. These layers of sediments were compressed over time to form the sandstone we have today. In the bottom left corner of the cliffs, the erosion patterns are contrived to show the configuration of the continents at that time. As the continents drifted, the sandstone layers warped, bent, cracked and parts were uplifted forming the escarpments – along the coast and along the Blue Mountains. Fine, windblown sand created dunes on top of the tilted sandstone monolith since the Pleistocene era, going back 1.8million years. It supports the delicate heathland we have today. In the textures of the heath, I have shown the mega fauna that lived during that time. On top of that, I have shown the Anthropocene,- our impact on the land. Below the sea, you can see hints of the life during the last Ice Age, when the harbour and the coastal shelf was dry land.

Our sandstone land is commonly thought of as mere quarry, but it is ancient and special. Everywhere you look around Sydney’s coastline, you can see the land is tilting away from the rugged cliffs on the coast towards the west. Sydney is a young landscape on an ancient landform. It is a flooded river valley formed at the end of the last Ice Age.

You have been a member and Deputy Director of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, expand on this position and trust and how many of the sites are now being used by artists?

The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust was established by the Australian Government to rehabilitate and open up to the public, redundant Defence lands around the harbour. It was established in response to community opposition to the sale and redevelopment of the lands. The sites include Cockatoo Island, the former Artillery School at North Head, various former army bases at Middle Head, Woolwich Dock & the former submarine base at Neutral Bay, amongst others.

We firstly had to earn the trust from the understandably suspicious communities. I was part of the team that developed a plan, based on a lot of consultation, to conserve the sites and establish new uses of the numerous military buildings. In addition to my work, I started doing pictures of the sites that helped illustrate the qualities of the sites that were valued by the community.

We sought new uses that suited public access and improved the public’s appreciation of the harbour locations. Some of those new uses include artist studios, at Lower Georges Heights and at North Head. In other locations, such as Cockatoo Island and the World War II fuel tanks at Mosman, they provide venues for performances, art installations and events. There are other important tenancies besides artists, such as the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, established at Chowder Bay by four universities. Their work is invaluable in improving our understanding of the marine environment of Sydney Harbour (previously not very well known or co-ordinated).

Nick drawing at Bronte, photo by Elizabeth Farrelly

Take one or two of these sites and show how you have interpreted the vista.

The first step is to pick the right view of an area so that I can bring together the main qualities or issues that I want to communicate.

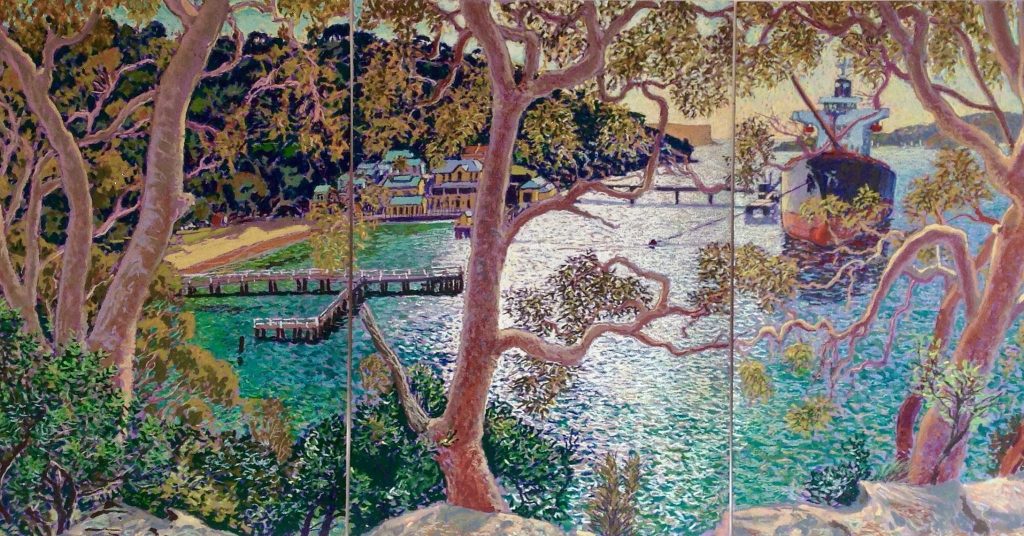

For example, in the picture of Chowder Bay through the Angophoras I chose a view from across the bay. It depicts one of the major, unique characteristics of the harbour: industry and shipping within bushland. Through the statuesque rose-hued trees, one sees into crystal clear water (perfect setting for marine research). Yet, there is an industrial jetty with a massive oil tanker. The cluster of timber sheds provide a village like ambience, stepping down to the water’s edge. Unlike other waterfront developments that have become yachting marinas, the Harbour Trust sought to use these terraces for a mix of social gathering places. The marine environment is for research, visiting boats and kayaking.

Chowder Bay through the Angophoras, Pastel, 59 x 126cm

The view tells us not only about Sydney but the story of Australia. We were the only colony that started after the industrial revolution had commenced. Consequently, the harbour is a sequence of industrial waterfront industrial villages surrounded by bush, connected initially by water and the ridge roads.

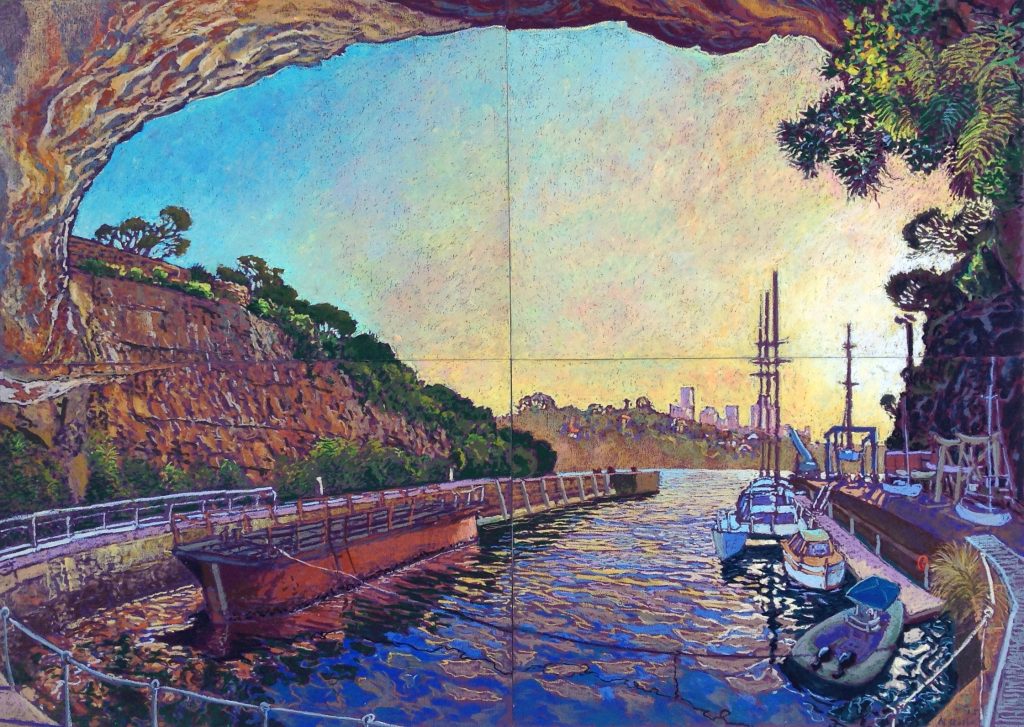

Another example is the dock at Woolwich. Again, it is a maritime industrial precinct within a rocky, natural setting. For a brief period, it was the largest dry dock in Australia. Part of its magic is that the end of the dock culminates in a cave, to accommodate the bow sprits of large, square rigged tall ships. So, I chose to draw the dock from within the cave. The contrast of the natural and man-made forms is a feature of our industrial waterfront. There is a wonderful sense of calm at the end of that dock, even when maritime maintenance is taking place. We, at the Harbour Trust, made it part of the network of harbour coastal walks.

Because Sydney Harbour is a flooded river valley, large ships could be berthed or built or off-loaded along the shores of the headlands. It was not a harbour that relied on constant dredging.

The Cove at Woolwich Dock, Pastel, 84 x 119cms

Your medium is pastel how did you come to this medium?

I came across oil pastel by accident. With the stress and pressure of my fulltime work and young children, I started going out to sit and sketch for short periods of time for a break.

Nick drawing at Currimundi beach, NSW, Australia

I discovered that by using oil pastels, pens and coloured paper, I could instantly create in full colour. After fifteen or twenty minutes, my mind completely switches off and, yet I produce something. The process is more important than the result. I was initially just interested in the air and the water: the light, the reflections, the ripples and the shadows. I soon became more interested in the landscape. Drawing with oil pastels became my way of savouring what I saw, caressing the scenery. It made me really look in a way that I don’t think I would have done otherwise

Discuss pastels and using them outdoors?

Using oil pastels requires little preparation and it is easily workable. Colours can be mixed, light can go on top of dark (unlike soft pastels) and yet it doesn’t smudge easily. You can have clear edges and forms if you want, or meld colours together. All I need is a shoulder bag containing a flat box with separate compartments for the various colours of oil pastels, folders of heavy, acid free coloured papers, brush-tipped pens. I carry a fold-up chair and I wear a wide brimmed hat. I take polaroid sun glasses and look at what I draw with and without the sunglasses. I can consequently walk and set up in small, often precarious positions. Because I draw on the papers I can carry, many of the pictures go across multiple panels (sheets) of paper. So, I firstly have to work out how the scene is to be arranged over the series of sheets. Initially, I draw across several papers to make sure the light is captured across the whole picture. I hold them on my lap and try to line them up with each other as best I can.

Have you had any ‘special’ or strange comments made to you while drawing on location?

People are mostly very considerate and polite. Some watch quietly and don’t say anything. Some ask, “Excuse me, do you mind if I watch you?” They don’t realise this is more disturbing than if they just did so, but they just don’t want to be rude. Some people want to take a photo of me with the picture or as part of their selfie. Surprisingly, none of this disturbs me… I can easily slip into my trance-like state of drawing again and again. I sometimes excuse myself for not talking to them. Occasionally my dog comes with me and sits with me. He is good at absorbing the attention that would otherwise be focusing on me.

Your initial training was in architecture, how often does a building call out for you to draw it?

Drawing is very important in all the phases of design and construction. It is an important tool for designing three dimensionally. I often start with a sketch of the space/spaces and then work out how they would be arranged in plan and elevation. I don’t think one can design effectively by only drawing the spaces after one has set out the plans – it needs to be the other way around. Drawing helps to tease out the main idea/ideas behind any design – expressing the forces that shape it. This isn’t necessarily what it looks like, so you need to be careful not to fool others or fool yourself. Finally, drawing is also an important way to convey what the building and spaces would be like. People need to see that properly and accurately – most people can’t read plans.

Although I was trained in Architecture, most of my work was in planning and urban design. I was and still am more interested in the spaces around buildings and the impact of buildings on our environment and society.

Take Harbour View over a Thousand Flowers and discuss the triptych from left to right and top to bottom.

This is one of my favourite views in Sydney.

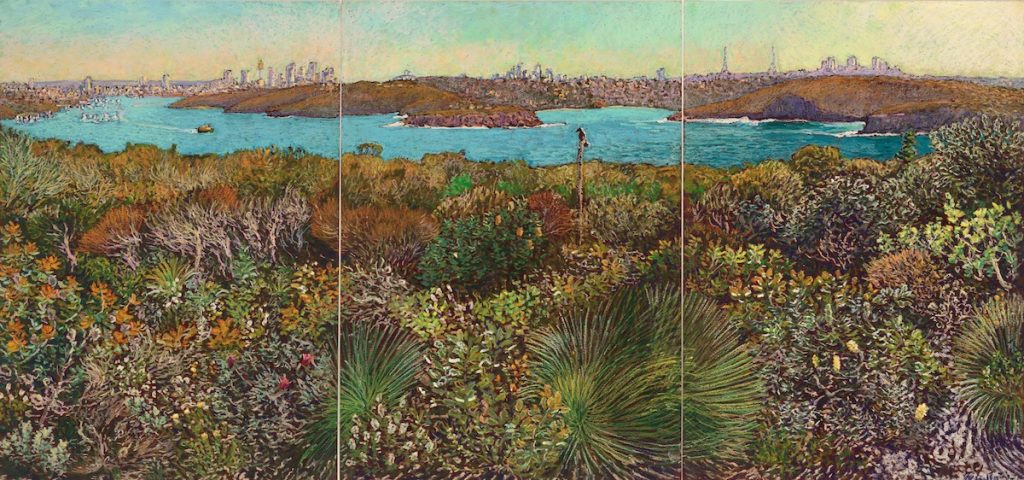

Harbour View over a Thousand Flowers, Pastel, 59 x 126cm

I chose to draw it because it shows the winding harbour recede into the distance over a foreground of the undulating textures and colours of the coastal bush. The name is a tongue in cheek reference to the orderly “mille fleurs” (thousand flowers) setting of late Medieval tapestries, such as the Lady and the Unicorn. Here, we have the real thousand flowers in wild nature. What is more, this scene is late autumn. I drew the picture over several weeks, in three sittings. I tried to show that here we have perpetual spring. There is always something new flowering.

So, the foreground is a sequence of rolling dunes with higher and lower bushes, ground covers and grasses. It is an endangered plant community known as Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub. The new shoots of the banksia, on the left, are a golden colour whilst the rest of the serrated foliage is silvery green. The lambertia formosa, a lantern shaped red flower was still in bloom and many white and yellow flowers were starting to come out. The golden brown, spindly leaves (flowers) of the casuarinas and the tea trees form a backdrop to the low flowers in the foreground. A bird landed on the spear of the xanthorea (grass tree). The fine, white sand that underlies the dunes is occasionally visible at the base of the picture on the right.

Seeing the harbour from this height gives an enormous depth of field. From left, one sees from the entry to the harbour to the city over the succession of headlands of the north shore. Then, around the point at Middle Head you can see Balmoral Beach and on into Middle Harbour. The ridge line is so important, yet we pay such little regard to what is built there. The landform and bushland of the outer harbour remains. The former military areas have defended the city not from some external enemy, but from our own rapacious development.

Where these divisions or three panels, obvious from the start or did they become more apparent with time?

When I pick the view that I want to draw, I work out how to arrange it on the paper, so I start at once with all the panels that I intend to use. In the case of the thousand flowers picture, I started with the three A2 panels and established where the scene in each panel would start and end. They don’t necessarily join seamlessly, but I don’t think that matters.

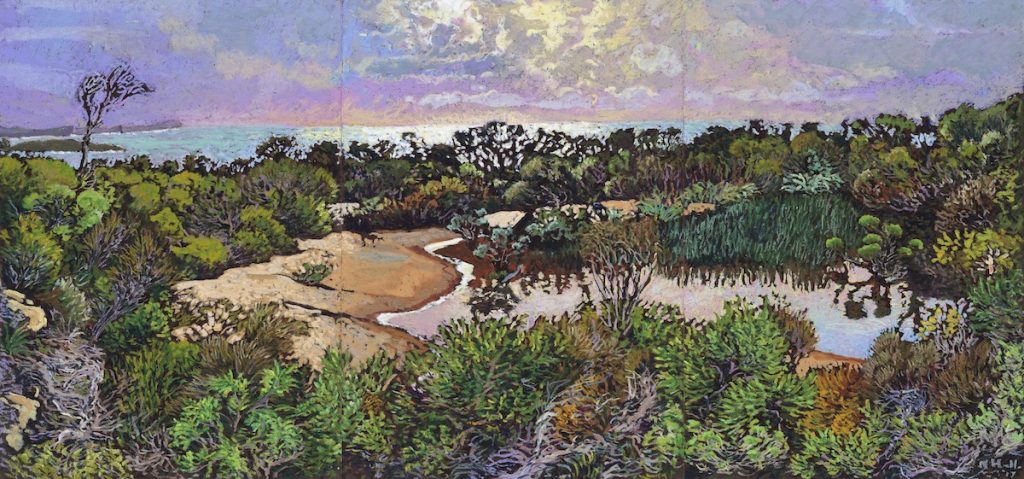

Elevated Wetland Overlooking the Northern Beaches, you ask can you see the heron?

Do you often do this ‘Where is Wally?’ in you work?

Do you have a hidden bird in all your work?

I draw what I see at the time I am there. Most birds, reptiles, animals appear cautiously and do not like to be seen, so I draw them that way – inconspicuous, partially concealed.

Elevated Wetland Overlooking the Northern Beaches, pastel, 42 x 89cms

Sky and sea are very important in your work – do you start with the horizon line?

Although my pictures have content and some even have a message, underlying all this, is merely my love of the nothingness and ambiance of space and light. I love the sea and the sky for that reason. I could just draw that quite happily, except it’d become boring and I think it is important to communicate about our environment.

I do start with the horizon line. It is how I tie together the picture over a number of panels. Although I distort the perspective and scale, I make it believable – you can’t tell when I’m cheating.

Your colours are very dependent on the time of day, discuss the effect of colour palette to light in your work.

The colours and forms are very dependent on the quality of light. I choose my colours intuitively – I don’t think about it, it just seems to happen. I often find that very bright light over sparkling water, requires a strong, dark (or red) background. We have to create the illusion of light. The landscape around us emits light. Our pictures don’t, so we have to create the illusion of light emanating from them. This needs contrast and other forms of trickery. Getting the sky to glow requires layers and layers of oil pastels – white, cream, green and pink graded and melded together with the peripheral blue. Reflection in the water has to glow. I use white and cream over the dark shadows that gradually give way to the translucent colours of the water as you look away from the glare. The shape of the reflections conveys the movement of water. In subdued light, there is always a predominant colour in the light or in the landscape. I seldom use grey or black, but create the effect through a combination of opposite colours like purple and green.

Is the size of your work dependent on the paper you use?

Yes, to some extent it is. I am limited by what I can carry. I use A2, A3, A4, and A5 paper. But I use multiple panels to make bigger pictures. The pictures that I make at home, when I want to compose the scene myself, are often made up of larger papers. The North Head Triassic Formation, for example, is one A1 sheet.

Expand on your own thoughts on the importance of artists as recorders in a historical sense.

As the world around us is changing, I believe it is important to document what we love about our surroundings. Over time, such pictures become a record of how things were. One can use drawings to accurately record the historical features of buildings and places, but I choose to “draw” out the significance of places. This may require subtle exaggeration and deliberately including or excluding some elements. I try to depict the ambience and quality of light. I do so because that is what I love, but it is also a useful vehicle through which I can communicate that love of the place to others. Drawing helps and encourages me to explore the background to the nature of things, what makes them the way they are, and consequently, to help identify what is precious about the place and in need of protection in the way we go about changing it.

The underlying message is that we have enormous power at our disposal and consequently, an enormous impact on others and on the environment. I believe we need to use that power wisely and gently.

Nick drawing at Forty Baskets beach, NSW

Contact details:

Nick Hollo

Nick Hollo, Sydney, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, January 2018

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: