Melissa Jay Craig Paper - Chicago, USA.

You make your own paper – what are the sources of your base materials?

More and more, the fibres I use are ones I harvest from my small yard, friend’s gardens, Chicago’s alleys or with permission from nearby nature preserves. Sometimes I make paper pulp with the harvest, and sometimes I use the fibre directly. When I need to buy fibre from papermakers’ suppliers, it is because I haven’t (yet) found a local fibre that matches certain qualities I need, like the high shrinkage, translucency and toughness you can get by over beating Philipine abaca. I also purchase large sheets of Korean Hanji paper because I don’t have a way to make that incredible material myself.

Can you give briefly the technique you use?

Can you give briefly the technique you use?

I’m not sure how to answer that because I use so many different techniques, often employing! Several in the same piece. I use whatever the particular work dictates, whether it’s harvesting and processing local fibre, making a thousand (or just three) sheets of paper, or building special equipment or single-use armatures. I am always learning or devising new techniques as well.

‘Fungus is the agent of change’ comment on this statement.

One of the functions of fungi is aiding in decomposition, in breaking down defunct organisms, directly changing the environment by cleaning up, clearing away, making room for a new system or life-cycle. Recent research shows that networks of mycelium also function as communication devices for trees, passing along vital information as a sort-of fungal internet, affecting change in a subtler fashion.

Can you expand on (S) Edition 99?

The title

The title is an edition that is also seditious in a sense, by challenging some of the assumptions of what an edition of books might be. Books – and paper pamphlets – are also the traditional ways that seditious ideas were once disseminated, small things that toppled governments and rearranged social order.

Why the large installation size?

When the edition is exhibited in its installation form, I want to suggest the seditious gathering of the title. That required a large number of copies. I remembered a quote by Clive Philpott, “Artists’ books are not artists’ books unless they are in an edition of at least one hundred.” So, I decided to make 99.

What is within the content of each mushroom?

Only the implied suggestion of spores. (The connection with books!)

What made you choose Amanita Muscaria mushrooms?

When I was a child, the first time I had the intriguing feeling that the planet carried secret messages (texts, if you will), was when I came upon a group of Amanita Muscaria, huddled together in a dark, secret space under tall pines. Amanita Muscaria, also known as Fly Agaric, is a fungus that can be found almost worldwide. It is distinctive, clownish in appearance, the ‘toadstool’ of familiar fairy tale illustrations; a literary fungus.

But it has its dark side as well: Amanita Muscaria is psychoactive, and is sometimes thought to be the source of the ancient shamanistic drug of knowledge, Soma. Reportedly, it is still in use as a ritual sacrament in certain Siberian tribes, and its use has been mythically linked to many ancient religions, including Christianity. Most shamanistic spiritual beliefs embody what would today be called an environmentalist viewpoint; they are also mystical, and embrace and honour intuitive acumen.

‘We are always reading’ expand on this comment.

We’re taking in, processing and responding to information everywhere, constantly. Reading doesn’t just occur when we’re sitting and staring at a printed page or backlit screen. We’re reading each other’s faces, postures, and body language. If you can hear, you’re reading the tone of voice. We all make judgments and decisions based on those things, often much more than on the words spoken. Likewise, we “read the room,” the mood of a crowd. We read the weather. To me, our intuitive reading abilities are the most intriguing aspects of our intelligence. They fascinate me.

Discuss the importance of written work to a person with a hearing impairment. Using Manifest O, to explain.

Text can offer clarity to someone whose hearing has been lost, provided that person is accustomed to spoken / written language. For instance, I can’t watch films, videos or television programs unless they are captioned. However, this is not true for all deaf people.

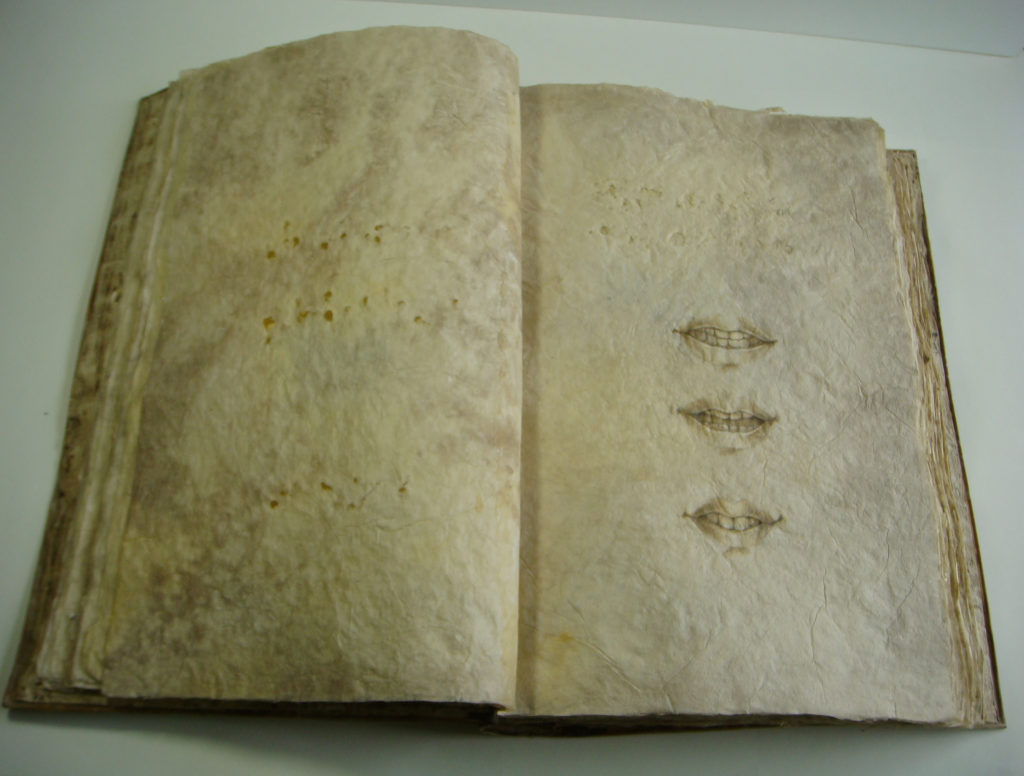

Sign language can be very much clearer than text to someone who was born Deaf, or whose early exposure is to visually based language. I’m someone who was born and raised in the hearing world; my deafness came after I had acquired spoken and written language. In Manifest, O, I tried to present my own experience of hearing loss by contrasting that with the expectations you might have of reading a conventional book. When you page through Manifest, O, you see that holes have replaced the letterforms; the words have all dropped from its pages. The paper feels fragile, cockled and wrinkled. Its colours are dull and muddy, with shifting patterns of intensity that don’t resolve into anything. As you turn the pages, you can see the drawings of mouths appear mistily through the translucent paper; portions also show through the text holes. You come to a page with a mouth making its speech shape, which repeats slightly altered on the back of the page, then disappears. You wade through more confusion, searching for the next drawing, the next hint. It’s quite frustrating to someone who expects to be following a conventional linear narrative. That’s how I hear: reading lips through a dull haze of indistinct, mostly meaningless sound.

Can you tell about your involvement with Columbia College, Chicago?

Can you tell about your involvement with Columbia College, Chicago?

I was involved with the Centre for Book and Paper Arts very early on, at an exciting time in its creation, and I also helped to develop the MFA in Interdisciplinary Book and Paper Arts degree program. I worked and taught there for fifteen years. I have taught at many other fine schools and arts centres as well. Though I do a lot less teaching now, it still remains a vital exchange to me, something that seems to be a natural extension of my own work.

Do you use the words on the paper you use?

Almost never, by choice, so that my work reflects my own movement through the world.

Discuss the importance of Installations in your work.

Discuss the importance of Installations in your work.

Installation has always been at the heart of my work. Even in the early days when I began making individual altered books, they all eventually gathered together into one large installation titled Library. I tend to think in visual, environmental and spacial terms. I even think of individual book works as being complete environments; you willingly walk into an installation, ready to read the elements you see there; you do the same when you open a book’s cover.

Perhaps I think this way because I derive my inspiration from complete environments. Lately I’ve been very pleased to be taking my work out into the landscape with the Monitors project and a few other experiments.

Contact details.

www.melissajaycraig.com

Melissa Jay Craig, Chicago, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, November, 2016

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: