Maiju Altpere-Woodhead Ceramic - Canberra, Australia

You have only been doing ceramics since 1993, what made you follow this medium?

I was born and grew up in Tallinn, Estonia, during the soviet occupation. In the early 1980s I was trained as an animation artist in the local cartoon animation studio ‘Joonisfilm’. Estonia was considered the most ‘western’ of the republics in the Soviet Union and the experimental film studio had an almost dissident reputation. It was an exciting place to work and I also tried my hand as an illustrator. After moving to Australia in 1992 I initially found it difficult to find my feet while literally living upside down. I discovered ceramics quite accidentally through an art course in the local TAFE and was immediately drawn to its materiality and processes, its rich possibilities and history.

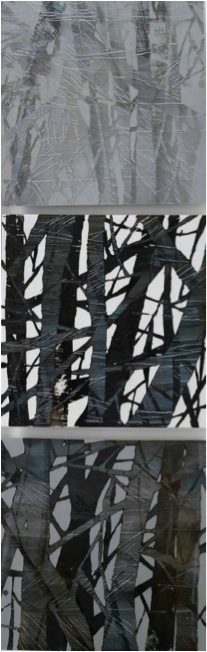

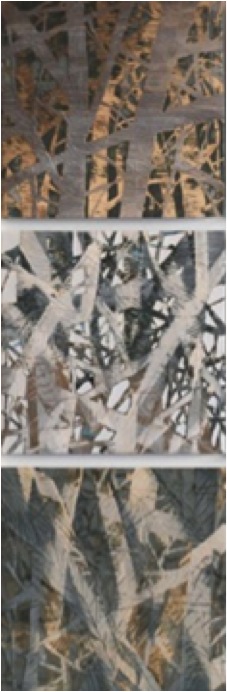

‘Soul’s Garden 02’ detail ’

As a new immigrant to Australia the art course in Nowra gave you both a feeling of belonging and a connection to your new medium. Can you elaborate on this?

At a time when the migration experience had seriously challenged my sense of identity and belonging, ceramics offered a sense of permanence, solidity and continuation. I suppose initially it was a healing process as the act of making followed by the transformative power of firing had a grounding effect on me. Soon, however, I realised that it was much deeper than that. I had found a new creative voice, an intimate language that I had been lacking in the foreign cultural and lingual context.

You have continued with a more formal education at the ANU can you explain this?

In Estonia I had missed out on an opportunity to formally study art whereas in Australia mature age students have an equal place in tertiary education. The Canberra School of Art at ANU offered a BA course in visual arts majoring in ceramics and I was accepted. For me it offered a possibility to learn from and interact with some of the best Australian and international art professionals and academics. After the completion of the BA degree, I also completed MPhil in Art Theory and Cultural Studies. The subject of my research was the relationship between material objects, craft based cultural production and migrant identity.

Soul’s garden series

mono-printed porcelain, oxides, erosion

100 cm x 100cm

How has your education helped in your artistic development?

From the outset of my study I had a rather clear vision of my long term goal as a practicing professional artist. That gave me the incentive to not only apply myself 100% to the given tasks but to seek additional challenges and opportunities that tertiary study can offer. Also, being a mature age student gave me the advantage of life experience to draw from. The course at TAFE had already provided me with good practical skills and technical understanding which are fundamental to any materials and processes based medium such as ceramics. University study added the conceptual and analytical skills which have allowed me to explore and expand beyond the boundaries of my own medium.

Ole Lislerud introduced you to mono-printing can you explain how you have adapted this technique to ceramics?

In 1997/98 I was fortunate to win a travelling scholarship and undertake a semester of study at the National College of Art and Design in Oslo, Norway. I had admired from afar the work and philosophy of both Arne Ase and Ole Lislerud who at the time led the local ceramics department. Now I had the fortuity to personally interact and learn from them. During my study in Canberra I had already started to explore the possibilities of combining various printing techniques with ceramic materials. Ole introduced me to ceramic mono-printing and a modular approach as a way to dealing with the size and scale limitations that ceramics inevitably poses.

Can you explain how you use plaster moulds and relief prints to transfer onto a ceramic surface?

‘Soul’s Garden 01’ detail

The ceramic mono-printing technique that I use in my work combines elements of two classical printing techniques. It utilises the spontaneous painterly qualities of monotype which is unique for producing only one print of an image. At the same time I also borrow from the classical intaglio techniques in which the image is incised into the printing plate resulting in multiple prints that replicate the graphic markings and textures of the plate. I start with a smooth plaster slab (the ‘printing plate’) that I cover with incised linear imagery. Over this matrix of graphic markings I start painting layers of coloured slips (these are my ‘printing inks’), scraping parts of them back much like in classical monotype. It is a spontaneous and rather intuitive process as I keep covering previous layers while working on the composition from front to back. As the surface imagery is built up layer by layer it also becomes an integral structural component of the resulting porcelain tile or any forms that I may be using it for. Finally I cast a thin (3-4 mm) backing slab of liquid porcelain which will act in place of ‘paper’ and lift the printed image. Once I have the print I usually work back into the surface by masking areas of it and carefully eroding the rest, revealing underlying layers of embedded colour.

Layers…. Your work requires many, many layers. Explain how you know when enough is enough, either added or removed?

‘Soul’s Garden 02’ detail

I use the physical layering of porcelain slip as a metaphor for memories and meaning, how they are created and re-created, arranged and re-arranged in a process with no finite beginning or end nor a set hierarchical order. I think memories in many ways are permanent. We don’t know when they actually enter and they don’t seem to leave, just go into dormancy to surface somewhere else. While I use the physical layering of different coloured porcelain, it is also about layering of memory, where you can dig and find something quite unexpected. I work quite intuitively rather than to a strict plan. I guess the basic sense of when to stop layering or eroding comes from both experience and the general idea I have for each piece. However, just like memory is never static, my approach fluctuates from piece to piece.

Colour and imagery are hidden in your work. Can you explain how you manage to work both upside down as well as having the insecurity of firing?

This is what I like about printmaking, working front to back and in mirror image. I like the way it removes me from my comfort zone and induces spontaneity. As I work I have an image in my mind, but I am very open to the element of the accidental that is the result of the processes and materials I have chosen. Firing is the most profoundly transforming part of my process, it can be both liberating and confronting. I have learnt to not be overly precious. If I wanted to just transfer or replicate an image, I would be working on paper.

Can you discuss your choice of colour palette?

I guess my colour palette is a reflection of my general aesthetic preferences. I have always been drawn to rather muted tones with an infinite range of subtle hues. I grew up in a Nordic country, where light and darkness have different rhythms and intensity to that in Australia. The twilight hours of short summer nights, the pervasive darkness in late autumn and winter, the blanketing whiteness of snow have all had an effect on how I relate to colour. Another, more practical reason is that I am working with high fired porcelain and only a number of colouring oxides can withstand the high temperatures (1300C)

Explain your work both technically and artistically?

I have always been interested in the reciprocal relationship we have with our natural environment and the natural rhythms that influence our life. Alterations and changes to that relationship have a profound effect both individually and collectively. That effect is not necessarily always negative, but often we only notice it, if it evokes a crisis of some kind. While the imagery of my work can be read as a reference to landscape or natural environment, it is not intended as literal representation of any particular location. Rather, it acts as a trigger for various abstract associations with natural phenomena and cultural expression. In the Soul’s Garden series I was contemplating the relationship we have with life and death, how different cultural notions and perceptions have been assigned to these realities. I chose the image of criss-crossing tree trunks and branches to create an abstract, pattern-like overall impression. It is not clear whether the trees are alive or dead or may be just dormant. Death, too, despite all its finality and devastation, can be beautiful. I remember driving through Snowy Mountains after the recent fires that had killed large parts of the snow gum forests. Seeing the vast swathes of white tree skeletons gently shrouding the mountains was overwhelming, both with its awfulness of what had happened and its visual beauty. I frequently use repetition to visually link individual tiles and whole series. It may be the obvious repetition of a motive eg. the branch or the more subtle accidental repetition of the incised linear imagery that comes from the continuous rotation of the printing plates. Another element that is characteristic to all of my work is the open boundary, where the image does not end at the edge of the tile. It is this aspect that I find most playful when assembling the fired tiles to create visual flow and imaginary space. As I make tiles in batches they are part of an initial composition. However, in the final assembly I tend to mix things up a lot and they rarely end up in the same order.

Can you explain the importance of place to your work?

Migration is a process of dislocation and transplanting, thus containing an element of existential crisis. It was that crisis that brought the notion of ‘place’ to my full attention and ever since I have been intrigued by the ways recollections of other places influence and inform one’s relationship with present surrounds. As new impressions are embedded into the existing web of sentiment and experience, the boundaries between past and present, old and new become blurred. Familiarity is found or formed through elusive associations with occurrences from the past and these associations themselves change from context to context.

‘Soul’s Garden 02’ detail

The size of your work – what are the restrictions?

Scale has always been the most frustrating aspect about ceramics for me, as the size of the work is directly dependent on the size of the kiln. Not many have access to large industrial kilns to fire monumental pieces. That is why I have resorted to working in modules. Combined with my interest in 2D expression, the tile is the perfect solution. The modular approach also allows for another element of my process, the post-firing assembly, when I work out the final composition. The basic process and technique remain the same whether I work on a single 33×33 cm tile, a 1m²piece or a 100m² composition.

Can you elaborate on the surface of your work?

The mono-printed and eroded surfaces have a painterly quality, superimposed with textured and defined graphic markings. The visual spaces resulting from this combination are complex yet undefined, with permeable layered depth. The fired porcelain obtains a tactile, almost seductive quality due to the raised relief against the smooth satiny surface. While the imagery of my work can be read as a reference to landscape or natural environment, it is not intended as literal representation of any particular location. Rather, it is to act as a trigger for various abstract associations with natural phenomena and cultural expressions.

Your studio: can you explain one or two aspects that are very important to you within your studio space?

Since 2004, I have been working from home in a garage converted into a studio. While space is rather tight (it also has to house a gas kiln) it is a wonderful place to work in. It is very private and filled with natural light. Light is probably the most important aspect of it for me, as my relationship with a place is greatly influenced by light.

Contact Details

www.maiju.com.au

Maiju Altpere-Woodhead, Canberra, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June, 2013

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: