Luanne Rimel Textile/Photographic Artist - St Louis, USA

Discuss why you tend to work in series?

The content of my work deals with Time, i.e. the passage of time, memory, remembrance, decay, and even persistence. When I become absorbed an idea, I seek out forms that resonate this idea. I begin to photograph in various sites and build a collection of images from each location. Then, one piece leads to the next and I explore how to make my thoughts into a visual expression. I work on several pieces at a time, feeling that they “speak” to each other and inform my creative process. Since the photograph is a primary component of my work, I look for compelling objects and forms that will eventually be part of my textile constructions. I am often asked, “How do you know when a series is completed and it’s time to move onto other imagery?” That is a difficult question and I am not sure I know a concise answer. When I notice that I am photographing a series of different objects or forms, I know I am being led in a new direction, and it’s time to begin a new body of work.

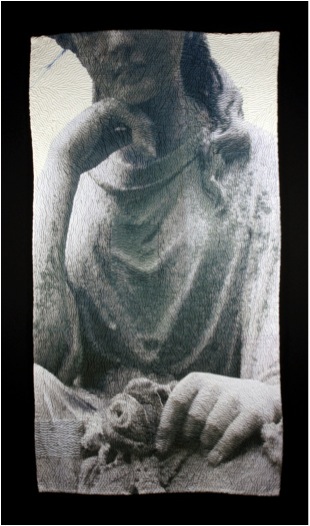

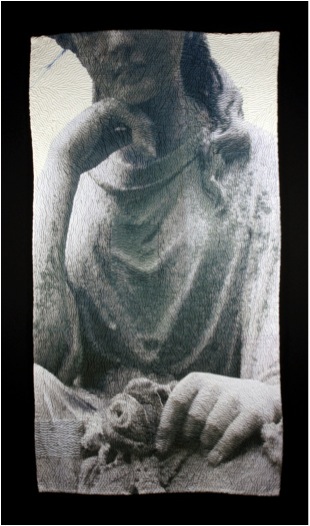

Your current series, that I saw at the Smithsonian Craft Show in April 2014 is very monotone. Discuss the photography in this context?

This current series involves detailed photographs of statues, with many taken in cemeteries. Even though they are color photographs and printed in color, the images appear monotone due to the materials used for the statue. Sometimes green moss or blue sky enters into the imagery, but mostly it is stone. I like what happens here because I think the subdued tonality of the photograph enhances the quiet simplicity and strength of the imagery.

You also place several images within the one image. Can you explain when and why you do this with some of your pieces but not all?

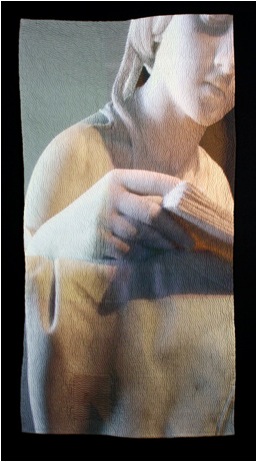

I do not have a studied background as a quilter, but I occasionally like to explore simple piecing and look for images that relate to one another. The earliest works in this series were pieced with multiple images. One work, “Silent Sound”, includes all images from cemeteries in New Orleans, Louisiana. The larger central image is of a statue and it is surrounded by a shadow image of iron fencing, and some colourful graffiti on the crypt of Madame Laveau, the celebrated Voodoo Queen. The smallest piece is a statue evoking the “silence” I refer to in the title. I also explore working with a single, powerful image for the entire work, as in “The Watch”. If one looks closely, they will notice the seams and realize they are also pieced in the same manner but with segments of the original photo.

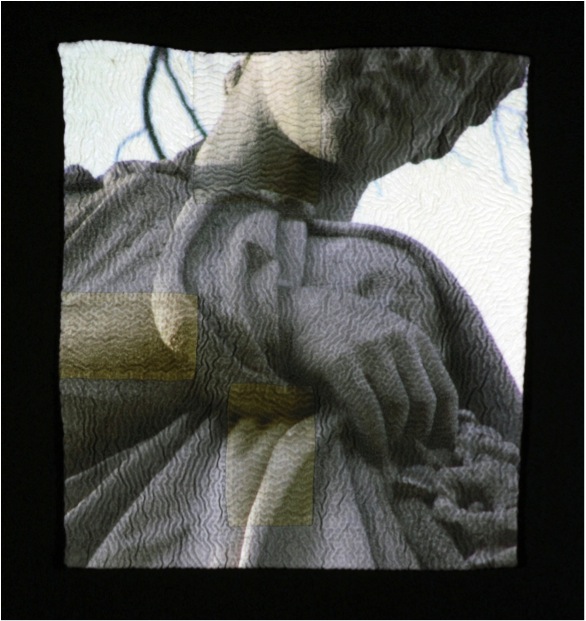

‘The Watch’

What background cloth do you use and why?

I am interested in the intersection of domestic practices and contemporary technology. In my current work, I use repurposed flour sackcloth dishtowels, as a metaphor for memory, women’s work, and family.

The act of washing and drying dishes has mostly disappeared in many 21st century families. I am the second oldest of six children and my sister and I would wash and dry the dishes for a household of eight every night, alternating the tasks from one week to the next. My memory of this chore includes singing along to pop music on the radio, telling jokes and laughing. When first married to my husband, (many years ago) on visits to his family, I would help his mother with the dishes after dinner. Only allowed to dry, not wash, I was instructed to get a dishtowel from the drawer and I have a vivid memory of the clean, neatly folded, bleached, white, flour sackcloth textile, with subtly embroidered birds or flowers at the hem. Once the task of “doing dishes” began, my quiet mother-in-law- would begin to converse about her memories of family, her children, my husband. The dishtowel, to me, represents a conduit to conversation and to memory. The images I print on this textile also become imbued with the history of this cloth. I could, of course, choose any cloth to print on and stich, but I am interested in the symbolic reference of this fabric and it is part of the content of my work.

Discuss how you use selected segments of your photographs (crop).

When I find and photograph a statue, I do try to imagine the textile piece I will create. I look for the best angle, the best light, the carved hands and carved folds of cloth. I may take several shots and then select the best for the final piece. In a Photoshop program on my computer, I crop the image to focus on the hands and cloth and select just the part that, to me, coveys a bit of mystery.

If one looks closely, they will see that every piece I make has one or more small hand stitched “patches”. There is no tear in the fabric; rather this is a symbolic gesture. I copy a small part of the original image and print it onto the cloth so it can be layered and stitched along with the quilting. This “patch” is symbolic because, for me, it is a reference to mending and repair, as seen in Japanese Boro textiles, my grandmother who darned socks, patched and reused textiles.

Can you give us a close up of the stitch work and discuss?

This is a detail of piece called Pensive. I begin the stitching by following the contours of the hand. Here you can see that the thread color matches the colors of the image so when it is pulled through the cloth, it becomes embedded in the slight puckers and is not immediately visible. These are running stitches, carefully places and gently stitched without any hoop or quilt frame. The repetitive hand quilting across the surface creates shadows and textures and alludes to the marking of time. Each piece takes its own shape beyond the original square format as the threads are gently drawn and pulled through the cloth.

How about the thread you use?

I try to use hand quilting thread whenever the color is a good match. I have also used machine quilting thread and other threads – it’s all about the color.

Tell us about the backing technique you use and why?

Since my hand quilting stitches are small and close together, I find that it is best if I only stitch through two layers of cloth. That way, the cloth responds to the needle and puckers a bit. Creating the texture. I use an heirloom cotton and bamboo, thin, quilt batting, and hand-baste the entire top cloth to it. Then I stitch, and stitch, and stitch. After all of the quilting is complete, I turn down the edges and hand stitch a backing cloth

The stitch direction?

As one works on a body of work, discoveries are made, and before long, you find yourself repeating an experiment so it becomes a technique. Several years ago, I was fortunate to be able to take a workshop with Dorothy Caldwell, where she introduced us to Kantha Textiles where the intricate stitched thread becomes imagery. I was already working with photographic imagery on silk, with some limited stitching and piecing. Following this workshop, I discovered that I enjoyed the mediative aspect to repetitive stitching and found myself experimenting more and more with needle and thread. I began following the forms of the photograph with the stitches and found that shadows were created depending on the direction of the stitch – then the experiment became a technique.

Do you use the stitch direction and closeness of the stitch to make use of shadows or do you vary the colour to the thread?

That is an interesting question – it’s a bit of both. I intentionally change the color of the thread to match the photograph, whenever possible, so that the imagery is foremost – its not an embroidery technique. The shadows the stitches create always surprise me and change with the light of the surroundings. I always begin with the hand, my focus, and stitch following the contours of that part of the photo. I then follow a more horizontal pattern for the rest of the image. The closeness of the stitching creates and almost hyper-realism in the photograph – the threads are buried in the folds of the cloth – and I am not aware of that until I pin it to my studio wall and look at from a distance.

Pensive

You have an emphasis on hands can you elaborate on this?

Many years ago, I was exploring the use of the hand image in other cultures and the various meanings it conveys, including identity and protection. Hands are so expressive, used in verbal conversations and as signed words for the deaf. I found that I was compelled to work with this imagery because it was imbued with so much symbolism. I did a series of photographs of the hands elderly women as they performed a routine chore, such as mending or washing dishes. I think that Time is reflected in the hands. That series is what led me to photographing the carved hands of statues.

You put an emphasis on hands. Can you elaborate on this?

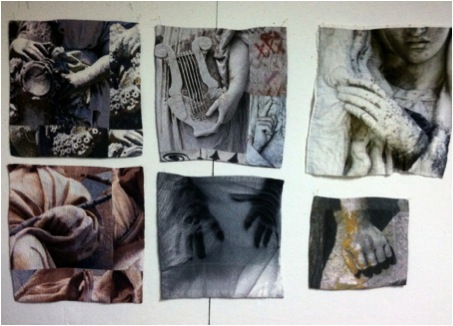

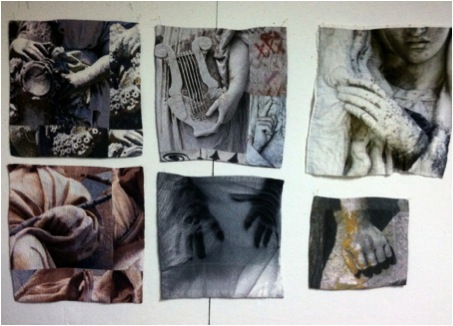

Studio wall image

Studio wall image

Travel has come from your art. Can explain two places it has taken you to?

Several years ago, I visited New Orleans and walked through the renowned cemeteries, taking photographs of the architecture and beautiful statues that inhabit those silent “cities.” The images from that trip are now part of many of my quilted pieces. For my last birthday, I wanted to seek out a cemetery in the US that has great statues. That request led me to Savannah Georgia and the Bonaventure Cemetery. That is where the piece, The Watch was photographed. I have received many suggestions from people who also appreciate the richness of the sculptures in cemeteries so I now have list of places I would like to visit one day. (On the top of the list is the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris!)

‘The Glance’

Your images are printed with an Ink Jet printer. How lasting will this be?

Inkjet printing has come a long way in the last 15 years. When I first researched this process the large format printers were still using dye based inks that ran if water touched them and did not work with fabric unless it was treated with another substance to “set” the dye. I spent over 2 years just researching and experimenting with this process. Now many of the printers have what are called “100 year” pigment inks – they do not even run when water touches them and they are much more colourfast. I look at this work as any drawing – keep it out of direct sunlight. The inks on works from over 15 years ago are just as they were when first printed.

Your printer gives you size restrictions? How do you overcome this?

This has been an interesting, and satisfying, problem. When I first researched inkjet printing of cloth 15 years ago, in graduate school, I was working on very wide printers and printing pieces that were three feet wide and seven feet long. I was not hand quilting those at the time, but creating whole cloth and layering.

When I needed a printer for my own studio, for financial reasons, I selected a much smaller printer that only has the capacity to print 17 inches wide. At first I worked smaller and within the parameters of the printer. But slowly I began dividing the photo on the computer and making much larger pieces, just printing in sections and then carefully assembling them together, as in a pieced quilt. I discovered I like the slight inconsistency of colour and the barely visible seam lines. Also the fabric I use, the flour sackcloth dishtowels are not large and work perfectly with my printer – a satisfying problem!

Do you feel that by transferring the the image onto textiles, especially old textiles, you are giving a warmth and softness that is not on the original image?

The photograph does get transformed on cloth. The print is softer as the inks migrate on threads a little bit more that they do on paper and it does soften the image. Depending on the thread count of the textiles, the results will differ, but I like what old lines and flour sack cloth do to a photo– there is some “nubbiness” inherent in the cloth. This adds to the imagery I think, and yes, give it a softer glow and warmth.

The Reader

Discuss how and where you do your hand stitching.

The hand stitching is actually the last step in the process. My studio is in my home, with a room for the fabric work and another room for the printer and computer. I will spend several days preparing the images on the computer and preparing the fabric to go through the printer. Then I print a few pieces, parts of pieces, and hang them on the walls in my studio. The larger images are pieced together, stitched and all are layered with the batting. I then hand baste the entire surface so the cloth does not migrate when I hand quilt it. The smaller works 10”x10”, are very transportable and I can actually work on them in a car when we travel. The larger pieces are quilted in the studio, slowly and methodically – it’s like a meditation for me.

Your botanical work is vivid and full of colour, expand on this?

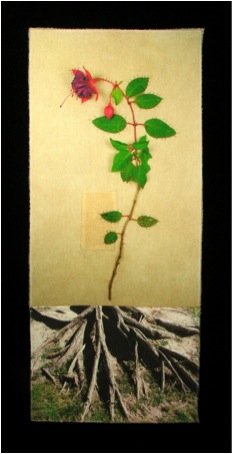

‘Fuchsia – Faithful’

I don’t alter the colour of any of my images so the botanical series is comprised of photographs of actual flowers from my garden or the garden of friends. I had been working with shadow images for some time and it was nice departure to surround myself with colour for a while.

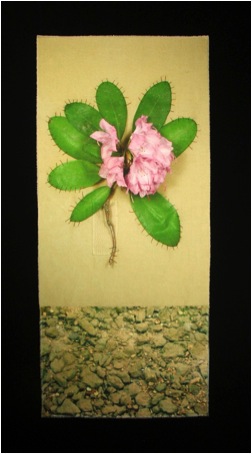

‘Rhododendron –Beware’

Explain about your Solo Exhibition at the Missouri Botanical Gardens?

I am an avid, amateur gardener and began the Botanical series when my husband, a metalsmith, and I were going to exhibit our work together. His work is about the land and I wanted to compliment this idea in my work. Following our smaller exhibit, I was invited to show my work at the Missouri Botanical Gardens in a much larger, public space. I created over twenty pieces for this exhibit, some large quilted silhouettes of flowers and the others were the colourful single flower images with hand quilted accents and stitched elements. It was a very large body of work and thrilling for me to see it presented in a garden environment.

Many of the flowers you use are chosen for their historical and symbolic meaning. Can you expand on this?

When developing this series, I was inspired by the classical botanical illustrations of the 18th and 19th centuries. I researched the meanings associated with flowers from the Victorian era and selected those flowers, many of them growing in my garden. (Such as Rhododendron-Beware, and Iris-Inspiration) .

Luanne Rimel’s Garden

Still working with my concept of time and memory, I cut a single flower, took it to my studio and carefully stitched it to a vintage dishtowel. I then pinned it to my wall and photographed it, sometimes waiting a brief period of time as the flower relaxed on the cloth. Then the process of printing this image onto another white flour sackcloth dishtowel began. The flower images were stitched to another image that represented the land. Some smaller areas were layered and quilted on the surface and included hand written text about the history of the flower.

Discuss the classes and workshops you do?

I teach photo transfer process both with and without a wide format inkjet printer. Some methods involve certain liquid gels and papers that allow a copied image to adhere to the cloth. Another, the one I mostly use, is preparing the fabric to go right through an inkjet printer. The image preparation is key to this method and time is spent on leaning to select the image or images that fit the student’s concept or idea and figuring out what will work best with the cloth. Last summer, I taught a weeklong workshop at the Arrowmont School of Art and Craft in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. It was intense, amazing and filled with creative and wonderful people who explored the many possibilities of these processes. Here at home, I often teach weekly classes on photo imaging on cloth at a local art center and about finding your “voice” in your work.

‘Silent Sound’

In your class, ‘Out of the Linen Closet’ you teach how to transform household textiles into artworks. Explain the importance of history and memory in your work?

‘Enigma With A Flower’

‘Enigma With A Flower’I have always been interested in ontology. I am excited about new discoveries in space, new planets, and conversations about the origin of the universe. By observing this vast picture, I look at the nature of the brief human existence and the bits and pieces that say, “We were here.” I believe that cloth holds memories, in smells, folds, stains. Old linens can tell stories of a life lived. I use cloth for those reasons and the rich history of cloth in many cultures. Cloth is also responsive and malleable. The slow, deliberate and repetitive stitches I use are symbolic for marking time, and memory, as they shape the final work. The images I choose are also about time and memory, from elusive shadows, to fading flowers and commemorative statues.

Discuss the importance of expanding photography from paper to textiles and how you came to develop this idea.

Putting images onto cloth is not new – (Robert Rauschenberg printed images to cloth in the 1950’s with screen prints and solvent transfers) – but towards the end of the last century and the beginning of this one – digital imaging processes became accessible to artists in all media. There were, and are, darkroom techniques that enable textile artist to create blue cyanotypes, or brown prints, and some photographers were developing their images on treated alternative materials such as wood and clay. However, the newer digital technology allowed for greater possibilities. From “iron-on” transfers to gel medium transfers to what I do – directly printing on cloth, the last 15 or 20 years have opened doors that were never perceived possible.

My goal was to have imagery on cloth that would retain the soft “hand” of the cloth. When I was in my late 40’s, I went back to school to get an MFA in textiles. This was about 1998. In 1999, the university I was attending was able to acquire a new wide format ink-jet printer for their Graphics Department. I received a research grant to explore this technology with alternative materials and my path then appeared. I was hooked, and experimented for another year before embarking on creating images on silk that were three feet wide and seven feet long. Photography stepped out of the darkroom for me. Cloth responds to the photographic image in a very different way than paper does. One has to be able to let the cloth speak, and soften the colour or the edges of the image. The photograph for me is not the end result but part of the overall process. The stitching enlivens the image, creating shadows and textures that are not possible on a paper photograph. There are artists that put images on cloth and there are artist that obsessively hand quilt for texture – I explored combining the two processes and my current body of work evolved from there – one step at a time.

Contact details:

Luanne Rimel

Website:www.luannerimel.com

Email:lrimel@mindspring.com

Luanne Rimel, St Louis, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June, 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: