Louise Saxton Mixed medium / assemblage - Melbourne, Australia

You do not see your work as textile art, rather Mixed Media Assemblage can you expand on this?

I describe myself as an “assemblage artist”, as my work is assembled from countless textiles fragments held together by delicate lace-pins. I also assemble other materials such as paper and found ceramics. Unlike traditional “textile artists” I do not make the materials myself, but rather rescue and reconstruct the handwork of others. I was trained as a painter and printmaker and now, with all the materials I use, the work embraces both art and craft traditions and references both painting and sculpture.

Feint Heart 2015 after Adrian Feint 1944,

Reclaimed needle work, lace pins, nylon tulle, 210 x 185 cm, Photo Gavin Hansford.

Can you expand on the way you use old embroidery in your assemblage?

My process is painstaking and involves collecting, sorting, cutting, colour coding and pinning the embroidery and lace, extracted from domestic table linens. I often re-interpret historical paintings using the textile fragments and for this, I first project the original image onto a ‘membrane’ of bridal tulle, which is pinned taut to my studio wall. I create an outline with large dressmaker pins and then, drawing from my pre-cut boxes of coloured motifs, I pin, unpin and repin until the picture is complete – much like a painter who lays down one colour, scrapes away, then lays down another colour.

Louise Saxton in her studio with Feint Heart 2015

Where do you source your collection?

My first large pieces of embroidery were collected during a visit to India in 1988, but the main source, over the past decade has come from charity shops and flea markets – at home and also whenever I am travelling. It has been a wonderful treasure hunt!

I am also fortunate, now that my work has more recognition, to be given several quite large family, or heirloom collections. These have mostly come from complete strangers in Australia, France, Canada and New Zealand. I also have two sisters and several close friends who have collected for me over the years. One friend from China gave me her own, largely antique, silk embroidery collection, which was incredibly generous and very unique! Occasionally, if I’m looking for something very specific I turn to the Internet to acquire pieces, but this is a much more expensive type of treasure hunt!

Palette of reclaimed needle work colour coded and ready for pinning

I personally love the word “disinherited” rather than discarded, discuss the important of this single word in the whole approach of your work.

I feel that both terms are important in reference to my materials. The word discarded is appropriate as many pieces end up in the charity shops or flea markets because they are no longer valued or useful to the person who owns them or their family. Sadly, some people have told me of collections that were taken to the rubbish tip, because no one valued them enough to even donate them! And disinherited is appropriate, and is somehow a more loaded or powerful word, because it is associated with personal loss – when family members decide their mother’s or grandmother’s needlework, which was made and/or treasured by her, is no longer important to the family’s sense of themselves without that person. I can now also add the term bequeathed to my lexicon, because the families who give them, value the items too much to see them dispersed through the charity shops and markets. They are looking for a new custodian.

How sensitive are you in the process of reconstruction. If and when do you say no to a particular piece of embroidery, and save it?

I believe I am cherishing and honouring the needleworkers in my process, even though it means destroying their original function objects.

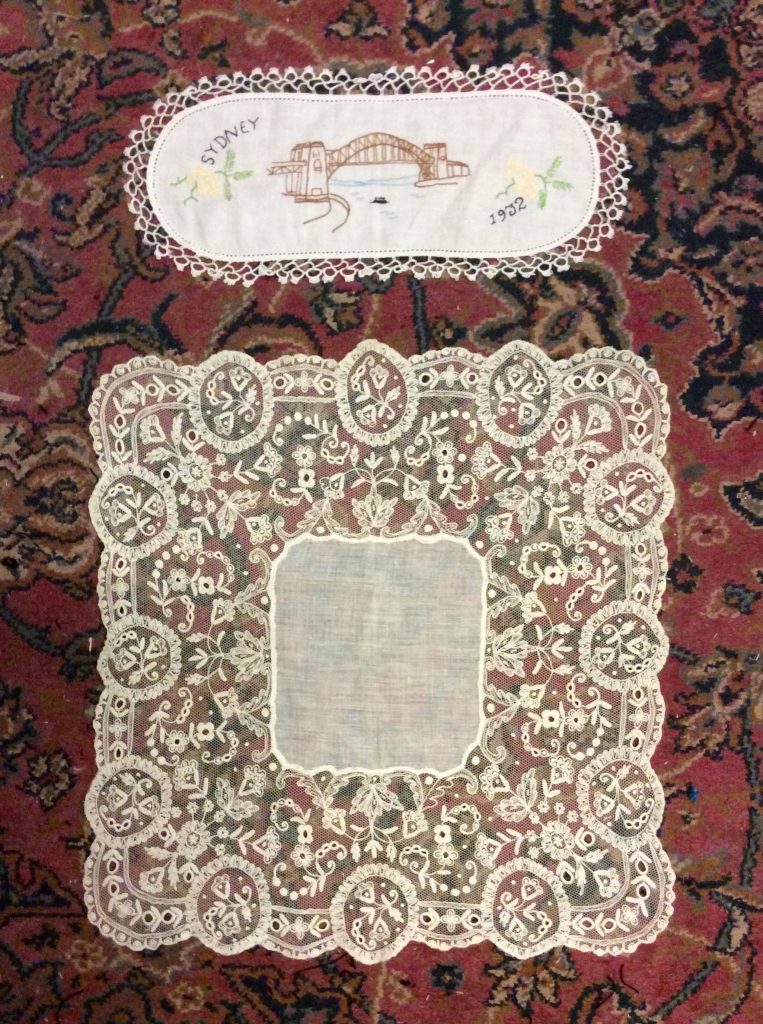

Heirloom needlework from France

It is rare that I buy or am given something I will not take my scissors to. In fact, it’s often the case that the more exquisite something is, the itchier my cutting fingers are! I have friends who’ve given me something saying, “but you are not going to cut it up are you?” and I’ve also been referred to by some traditional needle workers as an “embroidery vandal”. I recently extracted four exquisite sprays of red roses, which my mother embroidered 50 years ago and while she made this piece with such love and care, I wanted her handwork memorialised in a work of art, more than I wanted to cherish the original functional object. Having said that, I do own two pieces I am reluctant to cut-up – one is an antique lace handkerchief given to me when I visited Paris in 2010 (at the beginning of my “textile odyssey”) and the other is an Australiana doily, which commemorates the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. I grew up in Sydney and my father walked across it as a young man, with hundreds of others!

Two inspirational pieces in Louise’s collection that she may never give up – vintage Australiana doiley commemoration the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and an antique lace handkerchief from Paris

Discuss your comment “I see the needlework as kind of an endangered species”

Since proposing a major body of work titled “Sanctuary” in 2010 for exhibition at Heide Museum of Modern Art in 2012, I have thought of discarded and disinherited needlework as an endangered species. This is because the material I mostly use is everyday needlework, made in and for the home, which is now culturally redundant. The traditions, from which the art and craft of domestic needlework come, are hundreds of years old and were always passed down through the generations. While there is a revival of interest in craft traditions at the moment, domestic needlework, particularly in western culture, will never be made in the same way again and so, in that sense, it is in danger of disappearing. I have noticed a significant dwindling of supply of the raw materials in the charity shops in the decade that I have been working primarily with needlework. This is also why I draw a link between the disappearing traditions of home and species in the natural world, through reinterpreting historical paintings of birds, insects and flowers – which are also in danger from climate change and encroachment on habitat.

Flaming Flamingo, 2011, after John James Audubon 1838, Reclaimed needlework, lace pins, nylon tulle, 116 x 98 cms,

Photo Gavin Hansford

Expand on the excitement of allowing beauty from the past to be given a completely new modern life?

After a decade working almost exclusively with salvaged textiles, I keep returning to it for its uniqueness as an art material. The beauty, colour, variety and precision of the original handwork (embroidery and lace) keeps me entranced, and sometimes I feel as if the women who made each piece are with me in the studio. That may sound odd, but I do feel at times that I am a custodian of these materials. For as long as I’m able, I need to keep them alive, by transforming the functional objects of the past into art.

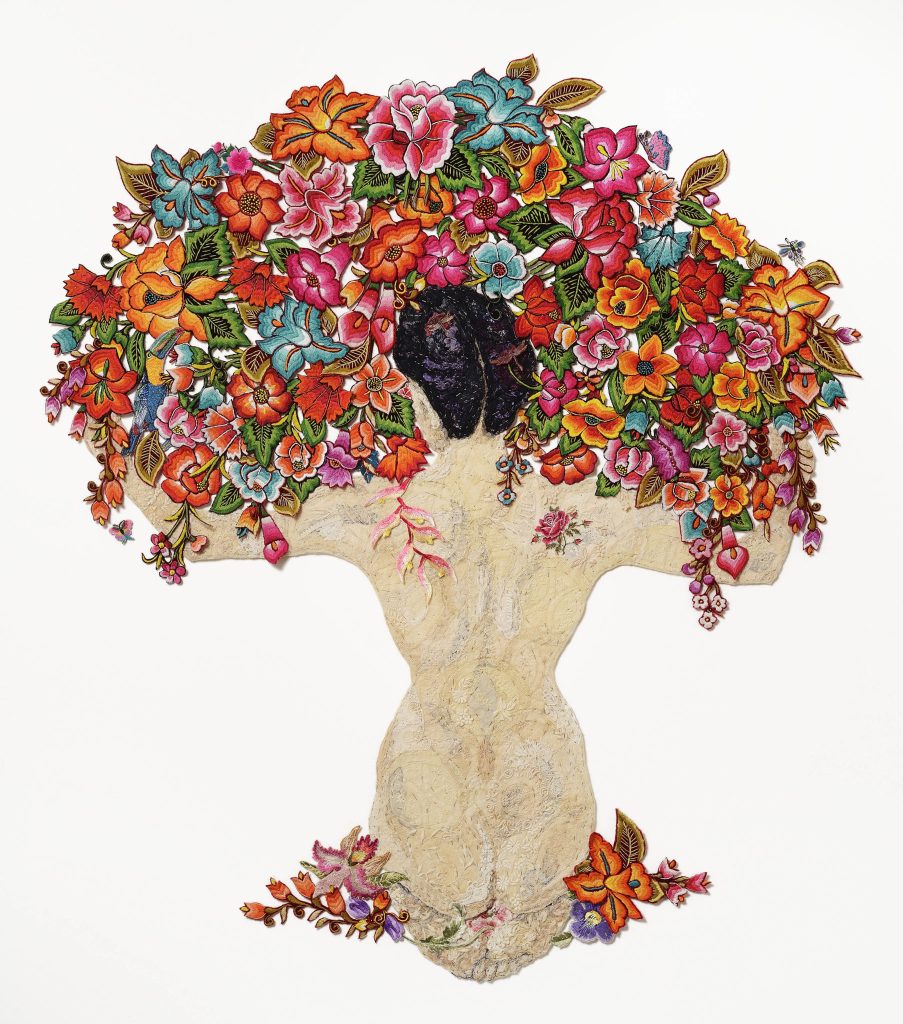

Desnuda y Flores, 2015, after Diego Rivera 1944,

Reclaimed needlework, antique lace doileys, lace and bead pins, nylon tulle, silk,

142 x 122cm, Photo Gavin Hansford

Discuss the importance of your residency in Mexico to your current work?

Apart from the opportunity for uninterrupted creative time, the month-long residency allowed me to briefly experience a culture that still has a living, albeit fragile tradition of embroidery. Mexico is renowned for its needlework and other centuries-old artisan traditions. The residency is situated on Lake Chapala, the largest fresh-water lake in Mexico and in an exquisitely beautiful region. The program was supported by fabulous hosts and a community of art lovers and through those contacts, I was able to source unique floral embroidery. On my return to Australia, this embroidery was incorporated into a major work, “Desnuda y Flores” (aka Frida) inspired by a Diego Rivera painting, which was the centre piece of my recent exhibition WILD at Gould Galleries. I have always found residencies to be deeply beneficial, both creatively and personally and 360 Xochi Quetzal Residency was no exception!

Ellis’ Paradise 2011 after Ellis Rowan 1917

Reclaimed needlework, lace pins, nylon tulle, silk, 142 x 99 cm, Photo Gavin Hansford

You use the work of historical artists including some notable women to as your starting point, discuss.

I turn to historical paintings by artists from the 16th – 20th century for inspiration and these have included people such as Maria Sybilla Merian, Elizabeth Gould and Ellis Rowan. I do this in order to draw a link between the domestic archives of home (embroidery and lace etc.) and the public archive of the museum and library, where many of the paintings that inspire me, are hidden away. I choose images that I find powerful, both visually and in terms of how I think they will translate into the medium of textiles. I am also interested in the anonymous or little known hand, which lies behind the famous and the well known (such as Elizabeth Gould, the wife of and painter for John Gould, the famous ornithologist and Lucy Audubon, the wife and business partner of John James Audubon). This interest in under-acknowledged forces in the creation of art, also links to my interest in the anonymous hand of the needle worker, whose painstaking and lovingly made objects I am reconstructing.

Black Prince 2011 after Louise Anne Meredith 1850

Reclaimed needle work, lace pins, nylon tulle, 97 x 73cm, Photo Gavin Hansford

Discuss the use of the fine bridal tulle as your background canvas.

Bridal tulle was ‘discovered’ by me more than a decade ago, to be the perfect medium upon which to hold countless textile fragments and pins. It is deceptively strong, so can withstand pinning on-masse and it is delightfully transparent – originally I created large installations from 3 metre swathes of the tulle attached directly to the gallery wall, upon which the embroidered motifs were pinned. The tulle had a delightful effect of being there, and at the same time, not being there.

Pins:

How do you use them in your final work?

When I first began using needlework and tulle, the pins were a temporary way of mapping out the work. I used a vintage sewing machine to stitch down a whole body of work, which were fantasy insects, but since 2009 I have used only pins to secure my work – whether sculptural or framed works. The pins have become an integral part of most of my assemblage works. Being metal, they add a material element and they add a visual element, as the gold and silver catches the light.

Non rusting brass lace pins with antique lace handkerchief and embroidery scissors

Discuss the importance of the historical value of the pin to your current work?

The pins in my work, which are countless, also reference pain – the painstaking traditions of needlework and of my own process; the actual pain of a pinprick and, the existential pain of knowing that all things pass away. And the history of the development of the pin is in itself fascinating. Originally an expensive commodity, pins were used to hold complex costumes together and one pin took something like 18 different processes to make. During the industrial revolution, the division of labour meant that the ‘pointers’ who ground the head of the pin, (in the semi-dark so they could see the point forming) had the most onerous and well-paid job. Consequently they inhaled thousands of tiny metal shards, which embedded in their lungs causing a fatal lung disease known as “pointer’s rot”. Needless to say they died an untimely death. I am often reminded of this gruesome element of the pins history when I encounter the sharp end of a pin!

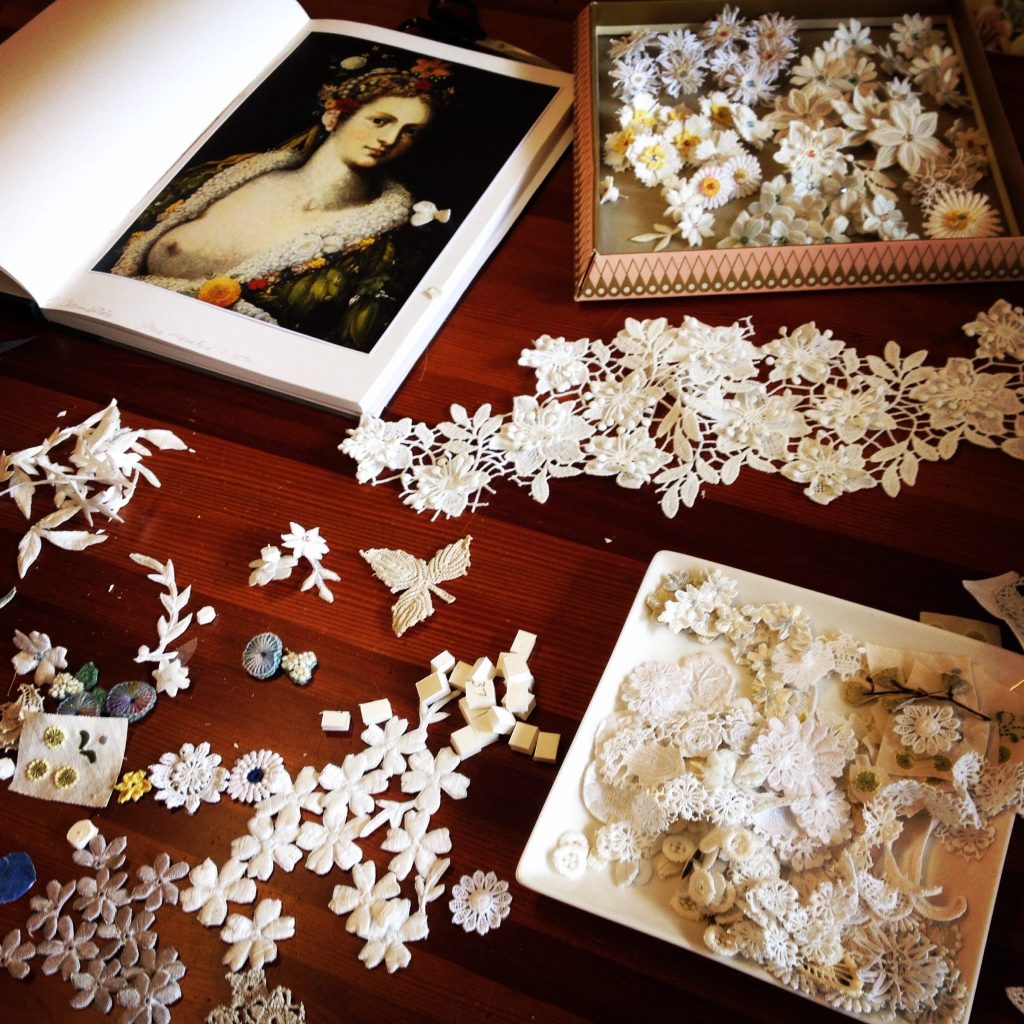

Take Flora and expand on the process you have used to make this work?

Partum Floralia (aka Flora) reinterprets a portion of a painting of the Goddess Flora, by Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1590. It was my goal for some years, to reinterpret one of Arcimboldo’s “composite” paintings and his portrait depicting flesh and clothing, hair and insects in lush flowers entranced me. The painstaking nature of my process and the detail of the original painting only allowed me to reinterpret a section of the original. I applied the same process I use for all my works, which closely reinterpret historical paintings – by projecting the original image; pinning the outline and then drawing from my palette of pre-cut needlework, I “paint with the textile remnants”. The work is made on a taut membrane of tulle pinned to my studio wall and uses stainless steel and brass lace pins. I also used a beading pin and a Swarovski crystal bead for each of the 250 individual raised flowers in the white fur collar! Once completed, the work is backed with silk and Vlisofix to secure the pins from behind and then for framing it is attached to museum board and foam core, using beading pins. This is a relatively small work at only 62 x 62 cm, but it’s huge in terms of the painstaking labour and time taken to bring it to life – to honour Arcimboldo’s original painting of the Goddess Flora.

Partum Foralia 2015 after Giuseppe Arcimboldo c 1590

Reclaimed needlework, lace pins, Swarovski crystal beads, beading pins, nylon tulle, vintage velvet, 62 x 62cm

Your work is also 3D discuss how this has evolved?

The shift from relief wall-work assemblage to more 3-dimensional sculptures has occurred over a number of years, beginning with more experimental smaller objects, such as a group of bird’s nests constructed from milliner’s straw. The largest of my sculptural works, Let the Jungle In 2013 was created from a 1.5 metre tall bamboo birdcage, designed to hold canaries, which I found in a Chinese emporium in Melbourne.

Struck by the object’s elegance and its innate sculptural qualities I began imagining transforming it from a cage into a nest – on a grand scale.I have also experimented with combining my textile objects with other mediums such as glass, in a small series of “pods” for my recent exhibition WILD, at Gould Galleries in 2015.

Let the Jungle In, 2013 detail

Reclaimed needlework, lace pins, nylon tulle, bamboo birdcage, copper wire, wool carpet, 150 x 50cm, photo Gavin Hansford

You have recently had a work experience student. Discuss the value of this to both yourself and the student?

I think this was an interesting experience for us both and particularly beneficial to the student from the local high school, who was on placement in the studio for five days. As an arts student she was interested in working in a creative industry and because of my past connections with the school (my son was a student there) she was put in touch with me. I devised a program, which would hopefully be interesting and fun for her (and also for me) which, involved assisting me in studio ‘production’ and some time on her own work. We also spent a day visiting exhibitions at the National Gallery of Victoria and several commercial galleries in the city and a day shopping for art materials in local charity shops. Emma also helped me with the production of the crystal-beaded white flowers for Partum Floralia (aka Flora).

Studio worktable with reclaimed needlework, journal, image of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s 1590 painting of Flora Meretrix, the Goddess of sensuality and abundance

Contact details.

Louise Saxton, Melbourne, Australia

Louise Saxton is represented in Australia by Gould Galleries, http://www.gouldgalleries.com

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, February, 2016

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: