Lise Bech BasketMaker - Southern Uplands, Scotland

Tell us about your local landscape and how this has affected your art?

When we moved to ‘Wee Darhunch’, a remote shepherds cottage over 28 years ago it had the potential to fulfil all our dreams: an acre of land, private water supply, no neighbours, no traffic and land to grow food, trees and willow for basket making and not forgetting a solid stone house, barn and the head of the River Ayr at our side.

We wanted to create a sanctuary for ‘man and beast’ having four dogs at the time in this green desert of constant sheep grazing, moor-burn and grouse shoots.

‘House and harvest’

Photo by Tara Fisher

You began making baskets as a way of making objects using organic material can you expand on this?

Having just begun basket making in Ireland under the tutelage of Alison Fitzgerald, I arrived with 100 willow cuttings ‘to keep my hand in’, which were planted instantly through a mulch of black plastic intended to keep the local grass at bay and giving the 12” willow stick a chance to send out roots.

We had no idea how well they would do as there was only one tree in the garden and over one mile till the next one…! In their first year willow slips need a lot of water but as that was coming out of the sky a plenty a bit of weeding was all the care they needed apart from a fence to keep the sheep and rabbits out.

The willow turned out to be the ideal pioneer plant with over 99% success rate and bringing in so many small birds. Over the years our postage stamp of land has become very bio-diverse micro woodland with four willow beds placed strategically to catch the sun and soak up the water. As the rods are planted 12” apart both in the rows and between the rows a small area can contain close to 500 plants, the close proximity forcing the new shoots to reach for the light and grow long and slender

‘Lise Bech – Harvesting’

Photo by Shannon Tofts

You personally grow your own willow how have your learnt how to produce the best material?

Over the years I have collected several varieties of willow with the intent of creating the broadest palette of natural bark colour available in the willow family. I have stopped at 25 different ones ranging from purple through browns, greens to golden and cream.

‘Willow bundels’

Photo by Lise Bech

How long does the process take from growth to having the willow ready for weaving?

They all get harvested / coppiced during the winter while the leaves are off and the plant is dormant. Harvested by hand using a pair of secateurs and cut one variety at a time, bundling them up and labelling the harvest straight away. I have never found an outdoor labelling system that survives, weather, weeds and dogs. I constantly refer to my notebook of planting schemes to get it correct.

‘Harvest Range’

Photo by Tara Fisher

‘Garland’

Photo by Shannon Tofts

By the end of February the harvest is usually over and it is time to grade the willow by length. I do this by standing the bundle in a deep barrel and pull out the longest rods first and work my way down to the smallest which could be 8’ – 2’. At this time the willow is heavy but delightfully flexible being 40% water. It should not be used for regular basket making as the resulting work would become very loose and rickety on the water has evaporated. However, I can make some art work pieces, garlands at this time.

The rest of the harvest is brought into the open barn where it will dry out over the following 6 – 8 months depending on the weather and the nature of each rod.

Storage and temperature must be a critical part of this process. Can you discuss this?

My making process does not involve drawing or a sketchbook. The traditional basket involves maths and forward planning as the size and height of the final piece determines the selection of materials. One of the wonders of willow is that it can have its flexibility restored by being soaked in cold water! This is possibly the most difficult aspect of basket making to get right let alone to teach as the length of the rods, the variety of willow and the temperature of the water and it can take from a few days to two weeks.

Please take us inside your studio and explain some of the special features you need for your art

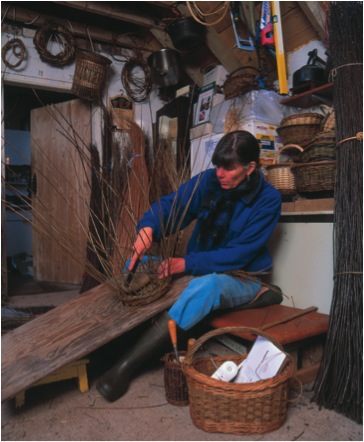

I share my working area with the power tools, the dog beds, laundry and boiler. This space was previously the cow byre and the only accommodation that has been made to facilitate my work is under huge roof windows that let in light from three sides. The raising rafters give me the height for tall work, while the rafters form ideal storage area and add scent and ambience to the space.

Photo by Shannon Tofts

I work on a low bench with my tools in the basket to my right and the willow on the floor within easy reach. Depending on what I am making I work on a sloping plank resting on my legs or the work is placed on a swivelling stool; this is also useful for appraising the work as by rotation it you can easily view it from many angles. As the larger pieces grow I have to stand and use my weight to form the undulations and make the border.

Can you tell us about Scottish willow and basketry from a historical perspective?

Margaret Fairnie in working clothes showing creel up close.’

‘Putting Creels on the tram ’

In the Scottish Basketmakers Circle we have for many years been aware that we are the receptacle of many stories about willow and basketmaking culture and for a long time we have thought a book was needed to hold on to it all. However, last year we got a grant to do formal research such as visiting all the museums and studying their collections and create a website which can be updated along the way. At an international conference in St Andrews in August 2012 the website was launched: www.wovencommunities.org

Having made a variety of replicas and reconstructions over the years working from a very worn and frail creel a friend and I worked out how the basket was made and made a pair of Eriskay creels for a woman who keeps ponies on the Isle of Eriskay.

Historical images from:

Woven Communities

Basketmaking Communities in Scotland

You received a Scottish Arts Council award, how this has affected your own work?

My early basketmaking was definitely a hobby, but in the process of wanting to learn I realised that the traditional makers had more or less died out and while on a courses we were learning from other hobbyists. Somehow this was not enough for me, so I went to meet Colin Manthorpe from Great Yarmouth, a man in his 60ies just retired form 45 years in the trade. I took as many classes from him as I could. This increased my confidence sufficiently to pass on my skills. At this time basketmaking was in the decline, the Scottish Basketmakers Circle was formed to prevent its death… Subsequently interest grew, sales and exhibition opportunities were explored and my teaching schedule became such that the day job could be ditched. This was a completely unexpected tangent which brought much joy and many new friends but over the years the teaching led me to a creative desert. A grant from the Scottish Arts Council enabled me to study with Klaus Seyfandg in Germany and Kari Lanning in California and to take time away from the order book for several months to develop new work which allowed the willow to speak its own language being; flexible, undulating, forgiving and kind, surprising… After 8 months I had moved away from the geometric forms of traditional baskets and before me a body of work, sculptural, asymmetric, organic forms which reflected both my surroundings – the lowland hills and my material and ultimately me as I rediscovered the joys and adventure of early basketmaking days and reconnected with the therapeutic value for which basketmaking is often derided, but has such potential in today’s world.

‘Hedgerow Cauldron’

Photo by Shannon Tofts

You take courses in basketry can you expand on this?

Most basketmakers live and work in isolation and often in rural areas with considerable distances to a neighbouring maker. I find essential to meet with others several times a year and I budget for Professional Development

‘Celtic Coil Couldon’

Photo by Shannon Tofts

Traditional basketry is still part of your work, how important is this aspect to you?

Without the skills that I have learnt from traditional basketry I could not make the new forms as they employ advanced versions of the basic techniques. Returning to make log baskets and shoppers, is as enjoyable as the adventures of contemporary work.

Photo by Tara Fisher

Many of the photographs of your work are done by Shannon Tofts. He added a wonderful artistic angle to your work. Is there much discussion between you both?

Early in my career when attending courses for emerging makers it was always stressed that having good photos was essential. I went to Scotland’s foremost craft photographer, Shannon Tofts. He took instant Polaroid images, so we could discuss angles, lighting before the final shots were taken. With digital this preparations has become easier. Over the years I have benefited much from both his craft connoisseur’s eye and his professional sill in capturing the essence of a piece. I now record the work I make from week to week employing insights I have learnt from Shannon. For important catalogues and the website I go back to Shannon.

‘Lise Bech – Basketmaker’

Photo by Debbie White

Contact Lise Bech

www.bechbaskets.net

Lise Bech, Southern Uplands, Scotland

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, July, 2013

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: