Kit Glaisyer Painter

Comment on how both your parents influenced your love of painting.

Looking back, I can appreciate that my parents were my first painting teachers. I would observe my father making pencil portrait sketches of us as I grew up, and my mother made small paintings of me and my brother, usually depicted as cherubs! Both of my parents were talented artists, and though neither went to art school or pursued art as a career, they both had some training and created very accomplished landscape and portrait paintings.

My father was a family doctor based in the rural village of Cerne Abbas in Dorset, southwest UK. He used to carry a small watercolour set in his car so that he could stop and paint local landscape views between visits to his patients. Back at home, he would then explore the views from nearby fields and, once I was old enough, I began to accompany him on his painting excursions. After working for an hour or so at opposite ends of a field, we would meet up to see what the other had done, and this was really how I began to learn what did and did not work in a painting, and to understand what my own paintings needed in terms of technique, mood, and subtlety.

Discuss the importance of landscape in relationship to light.

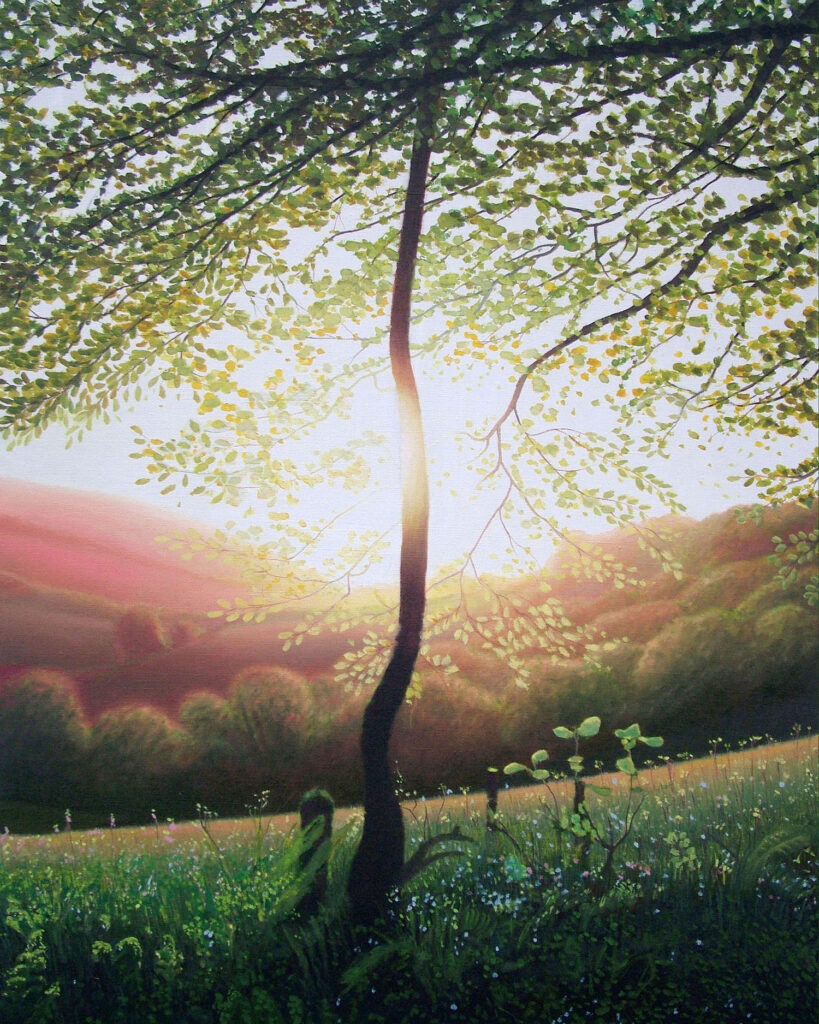

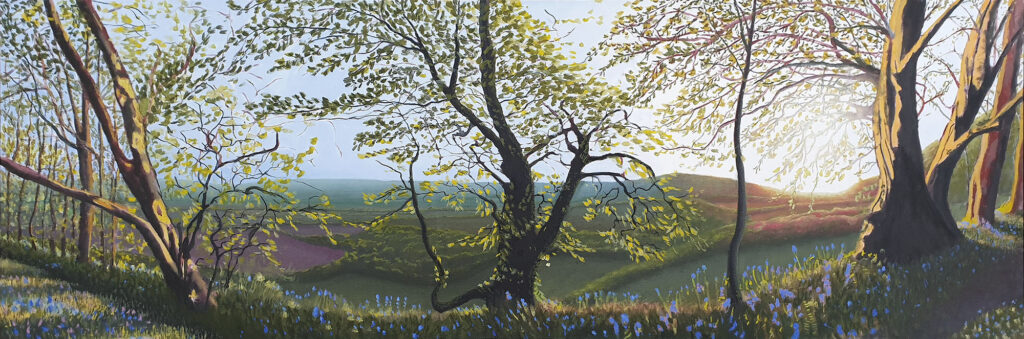

My painting ‘Young Tree on Lewesdon Hill’ captures the brief few minutes as the sun sets behind a young beech tree on the path up the hill. I seek to capture the sun in its most dynamic essence, rather than simply painting an orange sphere in the sky. I wanted to make it feel like the viewer was hardly able to look at the painting because the sun is so bright, appearing to almost melt the tree trunk as it glistens through the leaves.

Sun setting behind a young tree on Lewesdon Hill – oil on flax – 108x140cm

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of creating light, depth and atmosphere in a painting. The West Dorset landscapes that surround me, provide me with countless ways to explore this, using complex and multilayered oil painting techniques to create dynamic optical effects.

I’m always on the lookout for distinctive moments to capture in paint. Growing up, I used to capture fleeting moments with quick plein-air paintings, whereas now I prefer to work more slowly, creating highly ‘accomplished’ paintings that require several weeks or months of work, extensive preparation and dozens of layers (glazes) of paint.

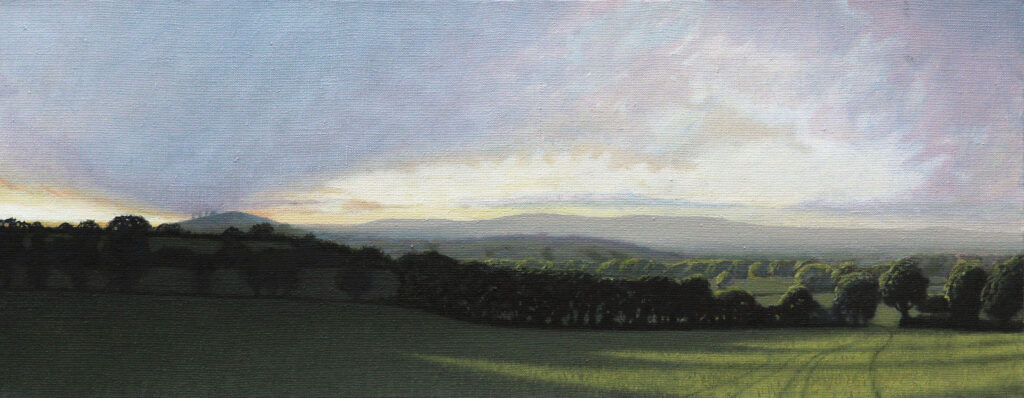

A view from Bulbarrow Hill – oil on canvas – 36x92cm

Expand this further to discuss Sky and how you paint skies.

Clouds

Every landscape painting actually requires a different approach to the sky, according to the mood and atmospherics involved. Some of my paintings have very simple skies because I don’t want to distract from complexity going on in the foreground or because lush foliage fills the upper half of the painting, so only glimpses of the sky are visible. Sometimes the mood of the scene is quite minimalist and meditative, so I simply create gentle gradations of colour across the sky.

A Hazy summers view across the Marshwood Vale – oil on canvas – 120x60cm

But sometimes, the sky can be packed full of drama and amazing spectacle, and then I thoroughly enjoy indulging in the theatre and cacophony of light, texture, depth and colour.

One of my most elaborate skies is probably in “Dorset Clouds above the Marshwood Vale”. For this scene I painted the sky with the canvas lying flat on the ground so that I could create pools of paint, overlapping, merging and multilayered, that mimicked the wonderfully dynamic cloudscape above.

Dorset Clouds – oil on canvas – 120x60cm

I never simply make up skies (or landscapes for that matter), everything is based on moments that I’ve witnessed in Nature, though many things may change in the course of making the painting. With my plein-air studies I simply respond to the scene before me, but with many of my studio landscapes, I sometimes combine two or more days into a single painting, particularly if I witness a more interesting skyscape that might better complement a splendid landscape that lacked great skies on the day.

North Bowood Mists – oil on flax – 100x40cm

Sunlight

Sunlight is so varied in its effect, sometimes bright and illuminating, other times more subtle and indirect. I’m always looking for dynamic moments to capture, and when they occur, I decide which vantage point will best suit those atmospherics. I have at least a dozen different places that I’ve returned to again and again over the years, some are epic views from hilltops, other are more intimate glimpses from behind trees, through hedges or looking up paths.

Eggardon light in the valley – oil on canvas – 100x40cm

When I’m looking for a grand landscape panorama, I often paint the views from the top of Eggardon Hill, an ancient hillfort in West Dorset. It’s a spectacular view, and because we’re so close to the sea, we often get low clouds and the sea mist sometimes creeps inland. This creates wonderful atmospherics of light, filtered through the clouds and mist. In ‘Eggardon Light in the Valley’ there is just a slim sliver of light between the land and the clouds, illuminating the valley below. Making a painting like this is all about patience, often working on just one area of the painting over several weeks to achieve the subtlety of colour and tonal gradation that it requires.

An October view near Whitchurch Canonicorum – oil on flax – 90x35cm

Dark skies

I often create compositions where there is a dark foreground, a light middle ground and a slightly darker sky. Some of the best skies are slightly stormy, with light breaking through the clouds and perhaps rainstorms in the distance. I also like to paint nightscapes, often with dark skies above a townscape or showing the moon above the sea.

The Last Cafe – oil on canvas – 210x70cm

‘The Last Café’ is one of a series of paintings I’ve made of a local café that I often stage in a theatrical manner. With this particular painting, I decided to show it as a large dark, empty presence against a dark sky, but with the dramatic light of the moon breaking through clouds and suggestions of civilisation in hints of light across a distant coast.

Litton Chaney Moonscape – oil on canvas – 210x180cm

For ‘Litton Chaney, Moonscape’ I went out for several nights to look at the moon above this small village close to the sea, trying to work out exactly what colours I was seeing. It’s a hard painting to photograph because I had to use a gloss varnish on the darkest parts of the sky in order to achieve a jet black. The cobbled road was actually an invention, so that I could reflect the moonlight in the bottom half of the painting.

Cafe Royal with cars 120x60cm

The feeling of the power of nature

Perhaps the power of Nature is best felt when we witness a dramatic sky above an impressive landscape. One of my favorite vistas is from Eggardon Hill, an ancient hillfort a few miles outside of Bridport. The views from the top of the hill are often totally breathtaking, and, along with the atmospherics in the moment, you can also soak up millions of years of history that have shaped the hills and valleys, matched by the hundreds of millions of years along the Jurassic Coast, where the south coast meets the sea.

Grant Panorama from Eggardon Hill – oil on flax – 240x80cm

Eggardon Hill has a crescent shape with a steep hill on the south side and escarpments a on the north side, which nicely frame the view into the valley beyond, which dips steeply towards fields and woods below. A few miles west, smaller hills rise and fall, with towns and villages dotted within the valleys, and further away, more hillforts of Lewesdon, Pilsden Pen and Lamberts Castle dot the horizon. The view of the sky is far broader from the top of the hill and can contain multiple weather fronts from blue skies one side to rain clouds on the other.

Discuss your plein air painting and how significant it is to your work.

Buckland Newton – oil on board – 60x40cm

As a boy, when I was working on my plein-air watercolours alongside my father’s often very accomplished paintings, the experience really helped me to demand more of my own work and to try to accomplish something equally engaging and surprising by tweaking the composition, improving my observational drawing, and honing my palette to maximise the visual impact of the image.

These early experiences made me appreciate that the challenge of creating an accomplished plein-air painting wasn’t just about the ability to capture a likeness of a scene, but about creating something truly memorable, by scrutinising the view and searching for areas to enhance or subdue, using one’s imagination to consider new compositions, and finding ways to push the available materials to intriguing outcomes.

I’ve continued to use watercolours throughout my career, and I can appreciate how they have greatly informed my subsequent relationship with oil paint, both in terms of their versatility and the way one can create luminosity by allowing a white paper/canvas to shine through the thin colour washes above.

My deep love of oil painting really started to develop in my early teens, while I was still at school, when I began to make plein-air oil sketches on board, mainly inspired by John Constable’s plein-air sketches, Corot’s paintings of the Forest of Fontainebleau, and Cezanne’s many paintings of Mont St Victoire.

One of my early oil sketches on board is of the Buckland Newton valley, where I grew up. I prepared the board before I went out painting, with a simple white ground. I thensketched the scene in pencil before applying thin washes of oil paint.

Homestead – oil on canvas – 30x24cm

A few years later, I painted Homestead with thicker oil paint, sat on the hill behind my parents’ house. Working for just an hour or so in the evening light, I started with a rough oil sketch, then, working down from the top, I painted in thicker layers, with the sky as the furthest background and then worked forwards, with the distant hill, then the woods in the middle ground, and finally the house in the foreground.

I find that plein air painting is a great discipline, but also has its limitations, as it very much depends on finding interesting light and atmospherics on that particular day. There are certain scenes that tend to work well with plein air, such as the light coming through trees in a wood, perhaps across a stream. Also, town scenes can be effective, or anywhere that the vista is interesting to look at in a wide range of lighting conditions.

However, for my larger compositions, the painting tends to be studio based, requiring several months of work to depict a relatively fleeing moment. In these cases, I tend to combine several plein air sketches with photography and collage to capture the essence of that moment, which forms the foundation for a final, highly accomplished studio painting.

North Bowood Sunset Clouds – oil on canvas – 30x15cm

You call your paints ‘Cinematic’ can you explain this term in relationship to your current work?

In one sense, the term Cinematic simply refers to the Panoramic format in which I like to paint, something that I’ve increasingly adopted over the years, usually preferring a 3:1 format. It naturally makes sense to me that, because we have two eyes, we automatically see the world in a panoramic format. While I’ve also made many paintings on a standard 3:4 or 2:3 format, I particularly enjoy how we have to ‘scan’ a panoramic landscape, unable to take in all the elements at once, but instead, focusing on one part at a time.

I am also a huge fan of Cinema, from the 60’s to the present day. In fact, my original intention was to first pursue a career as a painter and then become a Film Director, something that remains at the back of my mind. I particularly love the cinematography of Roger Deakins (No Country for Old Men, Fargo, Skyfall, Blade Runner 2049), Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire), and Michelangelo Antonio (Zabriskie Point). One can perhaps imagine some of my paintings as the backdrop to a film, and in fact, if you watch the beautiful 2016 version of “Far from the Madding Crowd” it is actually filmed in the countryside where I live.

I also feel that the Landscape can contain narrative elements without needing to actually tell a story. And while I’ve enjoyed creating invented scenarios around my Café Royal paintings, I realised that I actually don’t need to invent any new narratives when I paint the countryside, since I can call upon all my accumulated childhood memories and experiences that are so innately embedded in my psyche.

I suppose, in some ways, I am returning to the original ideas of 19th Century painters, particularly those of the Hudson River Valley and European Romantic painters, visions of the land that Cinema’s greatest Directors subsequently borrowed in order to add atmosphere and grandeur to theirs films.

Discuss the way you paint, moments in time.

Before starting a painting, I spend a considerable amount of time on research: first exploring the location by walking, sketching and taking reference photographs, while searching out the best vantage points, all the while waiting for those magical moments of light and atmosphere that might just inspire an exceptional painting. I have also been known to wait several weeks for dull weather to transform into something more theatrical or sublime. And when that moment arrives, I know I have to act quickly, devouring as much information as I can in the brief window that all the elements are in place.

The Offwell Valley in Devon – oil on flax – 130x48cm

Once I’ve got enough reference materials, I then begin to create collages with which I can explore ideas, design compositions and craft pictorial narratives. This all leads to a concept sketch that evokes the mood and atmosphere I want to capture, and I then start on some initial oil sketches on a small scale, with my collages as reference.

The early stages of a painting tend to be quite raw with strong colours and vivid tones that I deliberately exaggerate so that I can clearly spell out the grand themes within the painting. I then begin to patiently build up the many glazes (layers) of oil paint required, gradually toning down the colour palette in order to achieve ever greater subtlety over the following weeks and months, all-the-while, improvising and adapting various elements of the painting. This intentionally patient process means that none of my paintings are rushed and I don’t ever feel that I have to compromise my ambition for them.

From then on, it’s all about my relationship with the painting, which will continue to evolve and develop in its own way until it’s finished. Because I work with raw oil paint, I tend to have to wait either a few days or a couple of weeks for a particular layer to dry. This also gives me time to consider which areas of a painting are either working effectively or are unsatisfactory and to imagine what I might do next. Sometimes the painting suggests surprising new directions, and at other times I simply continue to follow my original plan, building up layer upon layer of glazes, gradually developing the dynamics and atmospherics throughout the painting.

I guess I see my Cinematic Landscape paintings as a hybrid of the past and present, eagerly drawing from various landscape traditions with which I combine the traditional skills of plein-air painting and studio-based landscape painting, while also utilising photography and digital technology such as Photoshop.

I should also point out that while my paintings often appear very realistic, I never simply copy a photograph and I am certainly not a Photorealist painter. And while I frequently utilise photography, it is mainly in order to capture fleeting moments, and so that I have some reference materials available to me several months after that particular moment has passed. Furthermore, once I’ve created the composition for my painting, I then break down every aspect of the landscape and then patiently rebuild every field, pathway and tree, according to the mood I’m seeking, through a patient process that is both improvised and exacting.

Another aspect of your work is ‘Drip Painting’.

Where did this term come from?

The technique I use to create my Drip Figures actually originates with my Abstract Paintings that I created in the mid to late 90’s. In these paintings I would drip and drag the paint across the canvas, and I learned how to use turpentine to ‘bleed’ lines and shapes out of the paint. A few years later, when I returned to the figure, I realised that I could utilise my abstract techniques to express the figure in a new way. It makes sense to call them Drip Figures because the paintings literally drip off the canvas. In fact, once I’ve painted the figure, I have to lie the canvas flat on the ground so that it stops dripping and freezes that moment in time.

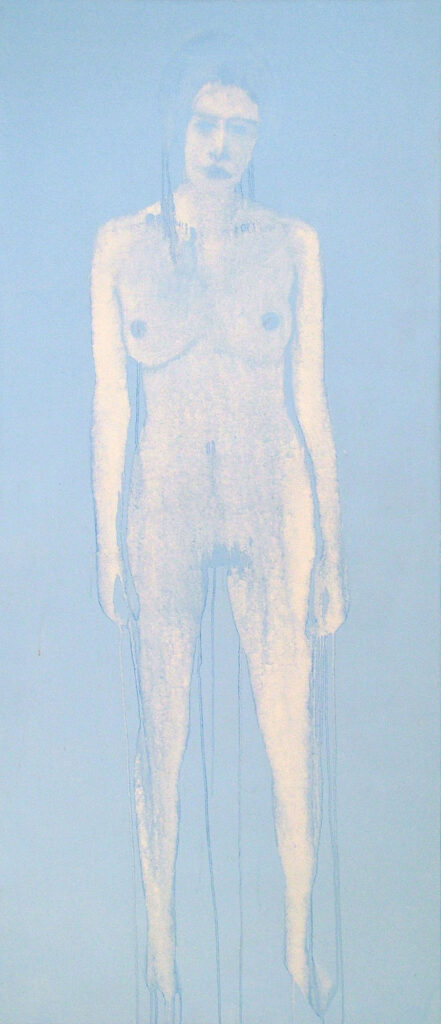

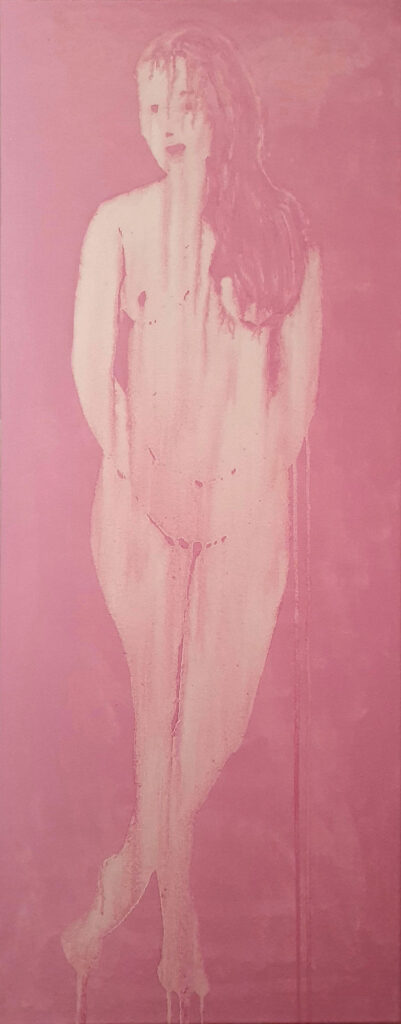

Drip Girl – oil on canvas – 180x60cm

How do you capture the figure within this work?

It’s all about preparation. I start with a flat layer of wet oil paint on the canvas, and I then remove the paint with turpentine, rather than adding paint, as most artists do! Painting with turpentine allows me to ‘feel’ my way around the figure rather than trying to depict something. Thus, I follow the contour of a shoulder or the angle of an arm, and I find I can express the dynamics and attitude of a figure through the movement of the brush across the canvas.

Sam standing – oil on canvas – 100x40cm

What I like about my Drip Figures is that they seem to have an actual presence, rather than simply being a depiction of someone. They literally emerge out of the paint, and the drips evoke how the body is in a constant state of change, as well as reminding us that the human body is full of fluid, which is both such a fragile and beautiful form to be living within.

Multicolour Girl large – oil on canvas – 100x40cm

How are you coping with the Pandemic and your art?

I am fortunate because I have my studio in my home, so I’ve been able to keep painting throughout lockdown. In many ways, my life hasn’t changed a great deal, as, like most artists, I’m used to working on my own for long stretches of time. What I’ve missed most are visitors to my studio, both the public and other artists, as I really appreciate and enjoy feedback on what I’ve been working on.

I started a new series of landscapes as lockdown began and it’s interesting to see how these each expressed a different emotional state I was going through, from stormy thoughts, to calmer moments and even some feelings of upliftment and hope.

How essential is your studio space currently in this particular time?

As someone who spends a long time on each painting, my studio has been a vital space. It’s in my house, so I can come and go as I please. After working for a few hours, I usually go for a walk or a cycle ride to clear my head. I find painting to be a very intense experience, often focused on a specific part of a painting that requires great subtlety and patience, and because I work in oil paint, there is always a sense of the narrow window of time in which I have to achieve the result. While it is always possible to repaint over an oil layer once it is dry, my process is pretty unforgiving as it often requires several ‘perfect’ layers to be applied in succession. It’s certainly satisfying once I’ve finished a painting session for the day, and when I finally emerge from the studio, it feels like I’ve been in a trance, so I need to reconnect with something ‘real’, whether that’s walking in Nature or enjoying the company of other people.

Comment on the value of other local artists to you?

Having the company of other artists is very important to me. Going to Art College was a revelation, being surrounded by so many like-minds (unlike being at school) and, since those days, I have always aspired to live close to other artists.

I moved to my current town of Bridport in 1998 mainly because there was already a strong artistic community here. The community had evolved from a short-lived Art College that was run in the early 80’s and which had essentially become an Art Residency, where artists from the UK and abroad could come to live and work. In 1999 the Residency closed, so I started a new art studio complex in a run-down industrial estate in the town. This grew over the years to provide studios for a couple of dozen artists and became a big draw for the town as a whole.

I’ve also been Director of Bridport & West Dorset Open Studios for ten years, so it’s been my business to know every professional artist in the area. I’ve now stepped down as Director so that I can focus exclusively on my own work and on promoting my new gallery project, Bridport Contemporary which is based on the ground floor of my house. I present a selection of works by a number of West Country artists that I particularly admire.

Take us through your countryside by season – discuss colours and how they vary.

Summer

“Hazy Summer in the Marshwood Vale” was a painting in which I wanted to capture the balmy heat of summer. The foliage and greens in the fields below are slightly bleached out, with a dry sun-bleached quality, while the earth is dusty, and the air, moist and humid. The overall palette is both accented to the brightness of summer light and slightly muted, as the hazy light reduces any great extremes of colour and contrast.

A Hazy summers view across the Marshwood Vale – oil on canvas – 120x60cm

Autumn

In “View near Burton Bradstock”, the evening autumn light is setting behind us, and illuminates the fields and trees beyond with an orange glow. Every time I went to study the view the pattern of light in the distant fields had changed, so I had to choose one particular day when the palette of the fields best complemented the glowing foreground. The distant valley was the last part of the land to complete, and once again, that particular day was chosen to work best with the rest of the painting. The sky above was finished last, though I had a clear idea of what it would look like from the beginning, with a cloud formation created by the warmer air rising above the sea on the right. I then blended the sky in with the landscape across the horizon in a naturalistic way.

A view from Bulbarrow Hill – oil on canvas – 36x92cm

Winter

Loders Road, Duck Street and Broadoak Road. I wanted to capture the stark, crisp January light in this series of paintings. The trees are bare, the hedges shawn, and the earth lies in hibernation, waiting for spring.

Loders Road – oil on flax – 30x60cm

The painting process is also looser and quicker, with thicker paint brushed on to rough, umber flax, which has had a layer of size (glue). Once the general composition is established, I tend to work from the back to the front of the painting, so that there is a crisp delineation of space between each plane of paint. The colours tend to be quite earthy in the spring, with more browns than greens, and showing a brisk clarity once the early morning mist has lifted.

Broadoak Road – oil on flax – 30x60cm

Spring

Lewesdon Hill is another ancient hill fort, much loved for its fields of bluebells and is one of my favorite spots to paint. The foliage gets particularly lush and verdant in the spring, with blankets of grasses, flowers, and leaves. I’ve painted two versions of “Lewesdon Bluebells”, the first was painted quite loosely and in an Impressionistic style on raw flax; the second, a more complex composition looking out from between three trees into the valley beyond. Here, the colour spectrum is rich and bright, with a wide range of greens, illuminated yellow leaves caught in the sun, and the distinctive blue of British bluebells.

Bluebells on Lewesdon Hill – oil on flax – 210x70cm

Bluebells on Lewesdon Hill – oil on flax – 210x70cm

What advice would you give your younger self?

What a question! I guess the answer is to work out what has brought me the most happiness and to avoid the things I most regret, and yet, surely, we have to embrace the unique journey that we’ve each been on? Looking back, I appreciate that I actually acted with considerable conviction when I was young, so I’d still endorse that. So, I’d highly recommend just getting on with whatever ideas occur to you, and avoid judging what you’re doing until it’s finished, for true originality must also surprise the artist in the process of creating it.

Also, find ways to constantly challenge and inspire yourself. I would be very bored if I had a completely premeditated process and a certain outcome. All of my most successful painting have been as much about discovery as creation.

Contact:

Kit Glaisyer

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, August 2020

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: