Kati Thamo Printmaker

You have been fortunate to win a Go Anywhere Grant discuss.

Yes, I was very fortunate to gain a Go Anywhere grant in 2010. It was a privately funded grant sponsored by Artsource in Perth to allow Western Australian artists to have the opportunity of travel to further their art practice. It enabled artists to undertake journeys to explore places that had particular relevance to their art making. For me it was an obvious choice of where to go – back to the family homelands in Hungary and Transylvania. Ever since I was child growing up in suburban Perth, I heard stories of the family’s remote Transylvanian homelands, a distant world so different from the hot, flat, coastal plain of Perth.

This was an exotic and mysterious world I’d only heard of from family stories or in fairy tales – of forested mountains, weeping deer, bears and wolves, village lives….… I had been a practicing artist for many years before getting this grant, and people were always commenting on how my work carried an Eastern European aesthetic, even when I depicted the Australian bush! And with the wonderful opportunity this grant offered I devised a journey from Istanbul through Eastern Europe and up to Berlin, spending time in particular in Transylvania, Romania and Hungary. It allowed me to visit the various places I had heard so many stories about. And in a broader sense, I was able to gain a sense of an aesthetics of place by visiting ethnographic museums, art galleries, cemeteries and churches alongside travelling through forests and villages throughout the region.

It was an enormously enriching experience for me to go back to the family village in Romania which even after decades still resembled the old black and white family photos I had leafed through as a child; there were still horses and carts loaded with hay, folk wood engravings on gates and fences and family homes filled with colourful embroideries.

Older people we met still had tales they remembered – of bears that hibernated in our family crypt in the hillside cemetery, of tulips in their gardens that came from my grandmother’s yard, of furniture taken from the home abandoned once my grandfather died. It was a journey dense with experience for me, to actually see the places I had only heard of in stories; an opportunity to place those many tales I’d been told in real settings; to go from the imaginary to the tangible.

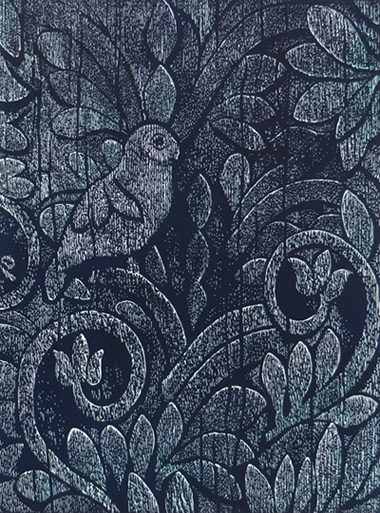

Ingrained, Flying at Dusk

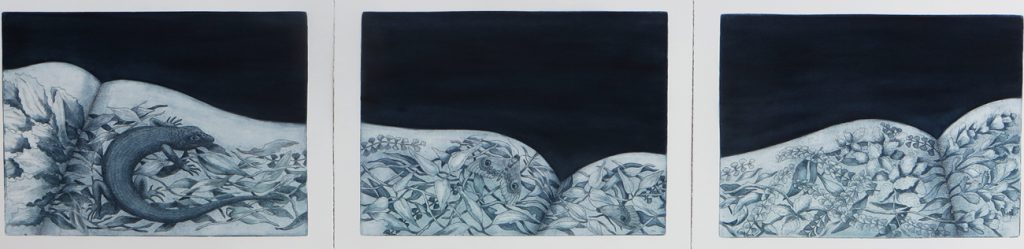

Since that fortuitous opportunity, I have produced several bodies of work inspired by my experiences. In the linocuts ‘Ingrained’, a series I am continuing to develop, I have created images based on the wood carved fences and arches common in Transylvanian villages. I’ve tried to re-create the patina of old engraved wood, and integrate my own imagery into the designs. Another ongoing sequence is a series of etchings, again based on my aunts vivid storytelling, which are more surreal and darkly fanciful, like my aunt’s stories were. In images such as ’The Land of Longing’ I’m not trying to depict an actual place, but to evoke the kind the shadow world she created for me, a world that has existed in a kind of parallel reality and which has it’s own bizarre logic.

Land of Longing

Although my art practice ranges across many themes, I think I’ll always somehow return to the strange and compelling world that was created for me at a distance when I was a child. Something about those family tales captures my imagination in a way that goes beyond the personal and particular to a more mysterious and mythic evocation of being in the world.

Explain how you are influenced by Folk art in your printmaking.

I grew up in Perth in Western Australia, the city to which my Hungarian parents emigrated in the years following the second world war. As with many other emigres my parents filled our house with decor that reflected their Hungarian/Transylvanian heritage. My old Transylvanian aunt also lived with us and sewed continually, cross-stitching blackly on red cloth as she embroidered tablecloths, cushions and napkins, and so our home was filled with the intense colours of Hungarian embroidery. And while my friend’s suburban houses had lino floors and paintings of the outback on their walls, our house had Persian carpets and oil paintings of Transylvanian village scenes. I grew up surrounded by folk designs, and folk art – there were decorative ceramic platters, jugs and bowls on display, and every Easter we would paint our blown eggs with decorative Hungarian patterns. Of course that folk aesthetic seeped inevitably into my own art making.

Ingrained

You comment, “My art is a form of storytelling with a strong narrative intent evident in my work.” Use 2 or 3 pieces to ratify this comment.

As I mentioned earlier, my old aunt was a great storyteller – hers were often dark tales of betrayal, loss and paranoia, and often strange and funny. It was the quirkiness that hooked me in and so perhaps she is the reason behind the storytelling impulse in my own art making. Though, rather than just illustrating these old stories, I’ve reconfigured aspects of them into visual metaphors, making a kind of fable or improbable account. And the same approach holds true when I create images from stories that are drawn from my own life or from dreams or myths. An incident in my daily life may make its way into my art making, to emerge with a twist, and holding several meanings that are more or less ambiguous.

In ‘Turn Around’, a triptych of solar plate etchings, I’ve tried to create a sequence of dream images based around a girl on a journey riding a bird towards a kind of lit stage. Were she to turn around she would see she was being followed by a hound, perhaps a wolf, but her attention is drawn ahead to where some folk are dancing, enthralled, to an accordionist’s tune.

Turn Around

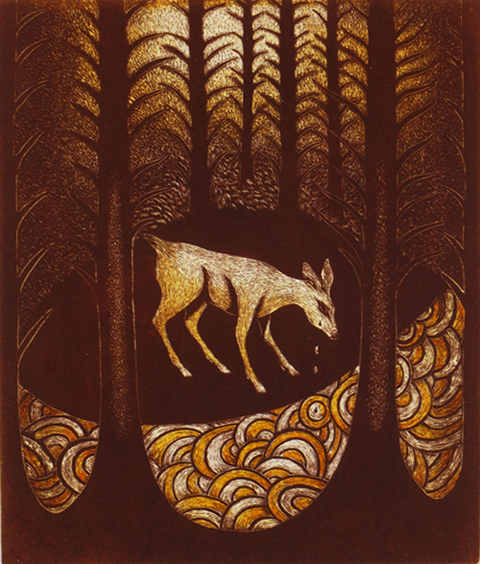

The ‘Deer That Wept’, another solar plate etching, is an image drawn directly from one of my aunt’s tales. She described once being in the forest behind her village and an injured deer came down to the nearby creek, and was crying. In my image, the deer that sheds tears into the water is not only that injured animal, but also stands for aspects of my aunt’s sad and thwarted life.

Deer That Wept

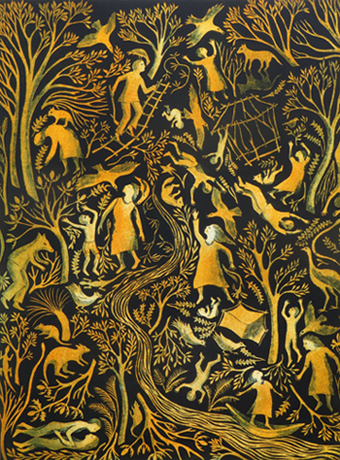

Another large collagraph print, ‘Unravelling Eden’ describes a period of our lives when we lived in the bush with our young children.

Unravelling Eden

I’ve referenced tapestries, or embroidered rugs, in this work, as while we lived there the forest did form the tapestried backdrop to our lives. The interlocking details within the image of people and animals refer to many of the incidents and stories connected to our experiences there. This is not a linear tale, but evokes a kind of song cycle, with a river flowing through.

Take ‘Another Song’ and discuss the technique, particularly the use of water colour?

In my etching Another Song I’ve used two plates to create a layered effect. The indigo plate shows the butcher bird which serenaded us on a high hill one day last year, singing to the banded rail that nests in our garden. The under layer of orange/sienna is another plate also etched with birds and flower details. I’ve included various native orchids in this image to reflect the delicacy of the rail, with it shy, graceful demeanour and intricate patterning. In this print, as with many others, I’ve used touches of watercolour to highlight a couple of areas.

Another Song

You often place your work within another context discuss.

Within a book

On a jar

In the last few years I’ve made a couple of large series of etchings. In one, ‘The Book of Nature’ there’s a series of linked images showing the pages of open books. In using books as the underlying image structure, I wanted to draw on a range of associations from encyclopaedia and scientific documentation through to illuminated manuscripts and sacred texts.

In Clear Air

This ‘book’ has no text but instead has intricate images of nature inscribed on the pages. The images are drawn from natural environments, are detailed and intimate expressions of place describing profusion, complexity and entanglement. And although each page has details of small plantscapes, there’s also a sense of a larger landscape of hills and valleys suggested by the book profiles, as one image flows into another.

Another series has been a sequence of images of glass biomes – etchings of small delicate environments which hold various plants, animals, birds and insects.

Wildlife Preserve

I started making images of birds and animals in bottles a couple of years ago, and the sequence has been growing. Where we live in Albany is only a small town block, and yet our yard harbours a range of wildlife. We have a bevy of bandicoots, along with frogs, ringtail possums, king skink lizards and a various birds – including the very delicate banded rail, which raises it’s brood under our mandarin tree every year. In making these works, I was thinking of our yard being a kind of biome, a small refuge where animals could shelter. On a larger scale the greater southern coastal region of Western Australia has established refuges on offshore islands along with fenced enclosures in national parks to hold and monitor various endangered species. Some of these animals, such as the Noisy Scrub Bird and the rare Western Ground parrot, have also ended up being depicted in my etched biomes. I quite like the ambiguity of these small scenarios – are the animals and birds trapped in there or are they being sheltered and protected? Of course there’s an association with specimen jars in museums, but my animals are depicted as alive and looking out at us, perhaps asking something. I wanted to capture a sense of fragility and also poignance in these images.

When I print these biomes, I cut stencils to mask out the backgrounds which makes the jars and bottles appear to float in space, creating a further sense of vulnerability – they could even be metaphors for our planet… floating in space and carrying this precious profusion of life.

Wildlife Preserve, Birds

So, yes, with these two series of works there is a very evident theme of containment. Whether in glass containers or in the pages of books, I intended these small ecologies to suggest the vulnerability, complexity and current fragility of various ecosystems.

You also print and paint on found pages, expand on this aspect of your work.

More recently I created a small sequence of watercolour and gouache paintings on the pages of old encyclopaedias, a place where information is collected, documented, collated and often ultimately outdated. On each of these pages I’ve painted a realistic depiction of a plant or animal. As I painted them I thought these specimens could act as a kind of foil to the information below them – offering something replete with it’s own ‘beingness’ and not necessarily fully explicable to us.

A large number of your works are based on Australian flora and fauna, comment on the deeper meaning beyond the initial observation.

I grew up in the suburbs of Perth, but moved to the country as a young adult, and have largely lived on the south coast of Western Australia ever since. For many years when my children were young we lived on a wilderness property, surrounded by forest and a proliferation of native vegetation along with native animals. The delicate tracings of foliage and branches thread through my memories of our years there. And even when we moved to the larger town where we still live, we are surrounded by national parks known for their plant diversity and profusion. So I have spent decades either living, camping or walking through the wilderness. That experience of being immersed in the bush, means the plants forms that i’m so familiar with become part of the patterning of my world. And the birds and animals I depict are often a record of encounters, like the butcher bird in ‘Another Song’ that serenaded us so effortlessly on a bush walk a while ago. In many of these works I’m attempting to express something of the exquisiteness of the natural world; to suggest something of the interlocking complexity and delicate balance in the natural ecosystems.

I’m interested in our relationship with the ‘wild’ – how we often romanticise it and yet inevitably damage it. Nature is no longer ‘unbounded’ – even the wildest, most remote places are becoming compromised by the damaging effects of humans. Closely attending to the natural world around us may help bring a shift of emphasis from a human centred view to consider other ways of relating to the world around us – to foreground wilderness as something worth attending to.

Using ‘Stitch Lives Together’ discuss…

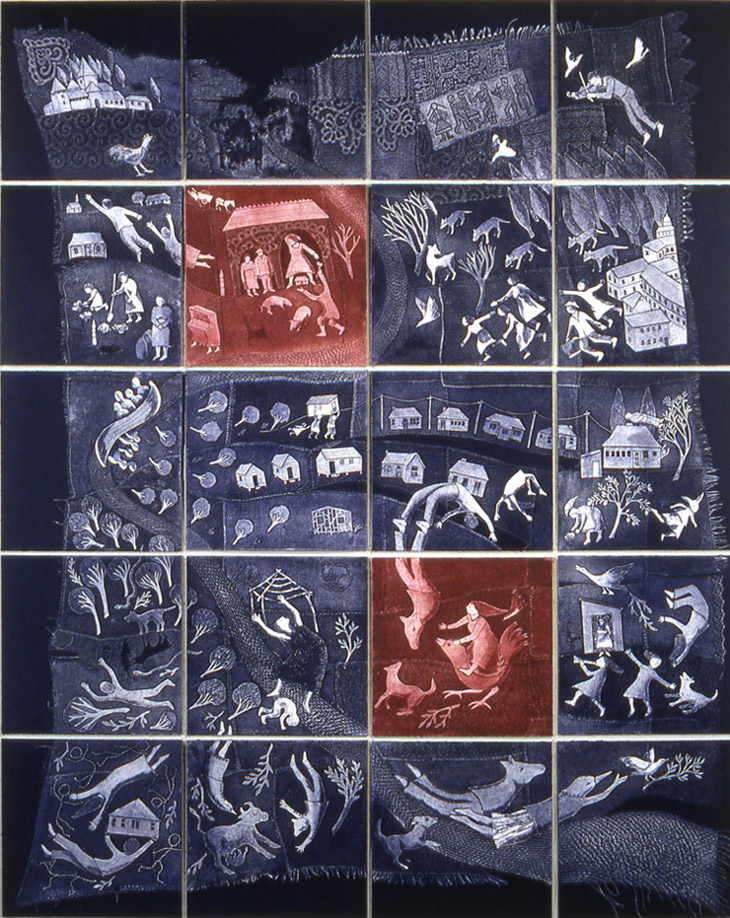

Stitching Lives Together

I created the large multi panel print piece, Stitching lives Together as part of my honours thesis when I studying at the University of Tasmania in 2001. It’s an autobiographical work exploring the interconnected stories of three generations of women in our family – my mother, my elderly aunt and myself. It takes the form of a large ‘quilt’ composed of twenty blocks, where a profusion of characters is overlaid on a patched background, tracing a visual lineage that stretches from Eastern Europe through to the Australian bush. I hoped to create a form of family ‘tapestry’, combining stories from my aunt and my mother and interweaving them with my own. it tells a story of dispossession and migration, and the adaptation of subsequent generations to a new land. There is a stitched ’river’ running through the piece, intimating how lives run into other lives, one generation flows into another, creating a continuum.

The collagraph blocks I used to create this work are made with stitched fabric and paper cutouts, with painted elements creating highlights and shadows. I often use multiplate printing as part of my process where plates inked in different colours are printed one over the other to give a richer depth and colour range to the images. Sometimes with prints I’ll create two series of the same image using different colours – with one edition in a pared back colour palette, and then playing around with a range of colours in a second edition to create a richer and varied tonal range. In this way the same image is imbued with different resonances.

You have many works bought into public collections. Discuss one of these.

Book of Nature

Last year (2018) I had an exhibition with Turner galleries in Perth called ‘Bird in a Bell Jar’ where I displayed the suite of etchings, ‘The Book of Nature’. I was very pleased when the Perth Children’s Hospital purchased the full set of 16 prints for their intensive care waiting room. I can only imagine how stressful it must be waiting whilst you child is in treatment, and I’m glad to be able to contribute some visual relief in that clinical environment. In the imagery for this compendium I’ve drawn plants and animals on open book pages, creating a sense of an unfolding story as you move from one image to the next. In many ways the Book of Nature works are a meditation on nature, and I hope the work will provide a kind of solace, or at least some calming distraction for those who wait.

Contact Details:

Kati Thamo

kati@katithamo.com.au

kthamo@internode.on.net

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June 2019

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: