Kathy Venter Sculptor - Salt Spring Island, Canada

You use very traditional techniques of hand coiling and pinching in you work, can you elaborate on your technique?

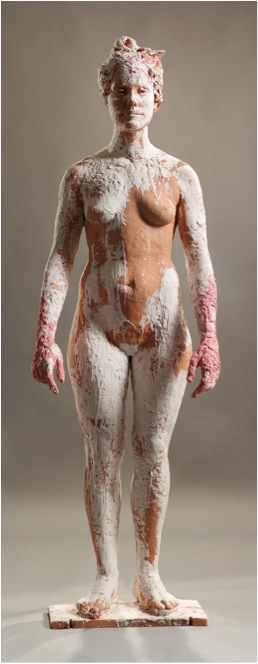

I began hand building by using the coil method. The application of a thick coil of clay around the circumference of the upper edge of the form and then pinching this coil to blend into the clay form below and upwards to extend and resemble the wall below. To follow the outer line of the form more accurately, I later used smaller lozenges of clay pinched into place. I’ve adapted this method to suit the specific challenges of creating figurative life-size work. Unlike many of my contemporaries, I don’t make use of any life casts, moulds into or over, or modelling over an armature. I finish the shaping of the area I built the day before by bending and paddling the wall – then add a new area of rough form above this and repeat the process.

The model poses for me throughout.

Kathy in her studio

Currently you have a huge installation at the Gardiner Museum. Could you tell us about your relationship with the museum? How ‘Life’ came about? The time line you had to prepare for this whole exhibition?

The Gardiner Museum is the largest museum of its kind in Canada and attracts visitors from all over.

The head curator – Dr. Charles Mason visited my studio having an idea in mind for a large scale exhibition which would be a strong and full use of the new space for contemporary ceramics being built onto the Gardiner at that time.

When he saw my work in person he felt this was an answer to the headache of whether a vessel form could ever be referred to as sculpture. The popular theory defined a vessel as any ceramic form enclosing a space – and sculpture not. The popular definition of the vessel as craft is seriously challenged in my art as the hollow clay form created in the making of these sculptures had no practical function and the outside form is obviously sculpture, i.e., fine art. But the technique of pottery making is the fundamental process in creating these works. I have a respect for the basic fundamentals of craft existing in the sculpture of all societies. The argument of art versus craft has traditionally had very little relevance in most societies and I believe that this argument has run its course in the contemporary debate. We have to remember that the work “art” comes from the Greek “ars”, which means craft. So during a period of high art, the best craftsmen were valued. In fact, my sculpture, because of the medium, consistently straddles what could be considered craft and what could be considered fine art. My work has only been exhibited in contemporary fine art galleries.

I had three years to prepare for the show, but this extended into six years because of other commitments for the Gardiner.

As well as the exhibition, there is a beautiful catalogue: can you discuss how this catalogue came about and your involvement in its production?

I had good documentation of all my work and Deon, my artist husband, put the catalogue together with the images relating to the text. The biography was compiled using images of our early life in South Africa as well as our immigration to Canada in 1989 and subsequent exhibitions.

Can you discuss the importance of humanity and community to your work?

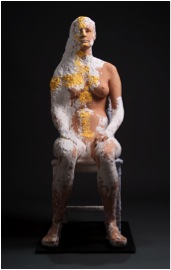

‘Coup d’oeil #5’

In the installation Coup d’Oeil the subject of our collective humanity and community is most evident. These young women are all friends and have been part of this community for most of their lives. Looking at them grouped in the sculpture they could have lived ten thousand years ago or they could be from our times. My intention is for these figures to have the appearance of life itself, in its own process of coming to be. They’re universal. I take the approach of depicting the living persona, without generalization or objectification. Artists have the freedom to also show the enduring qualities in humanity, the strength within society as well as reveal our spiritual capacity. In this way the themes of our humanity are the visions of our poetic intuition and define our emotions. The human body is a universal for all cultures. Our past is linked to our present and all cultures through our humanity.

Ceramics and Sculpture are both part of your art practice, can you elaborate?

During my years at art school sculpture was my major and ceramics one of my subjects. I loved both and discovering an affinity with clay, I joined them together.

Your work is life size how do you get this to work taking into account shrinkage and breakage during firing?

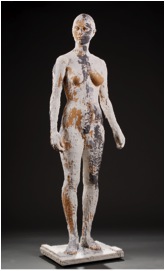

‘Even Telling’

I build the figure approximately 15% larger than life size to allow for the shrinkage during drying and firing.

The Salt Spring women: can you discuss your relationship with these women?

Also your relationship with the tribal children in the Ciskei region ? Inspiration, location and artistic issues?

Using models of young women, from my community in the transition stage between child and womanhood, I could draw inspiration from my visual knowledge of the same stage of development in the tribal, Xhosa society in my area of the Eastern Cape in South Africa. There is a duality in the human form at this stage, sometimes both child and adult are evident, then again, only one or the other. In the Hogsback near our hometown of Alice in the Republic of the Ciskei I encountered children who made tiny figures of kudu and wild boar. Their sculptures were an immediate response to the primary experience of life there, with no exterior or learned referencing. About seventeen children supported their village by making these small clay images of animals. Walter Batiss, a local professor of art and painter, gifted some of these to Picasso who admired and collected them. Even if these sculptures were made on site with no knowledge of what art is, or potentially can be, these sculptures are high art and ultimately spontaneous. These children are creating forms in response to their own cultural matrix and yet they can be understood by all cultures. These sculptures are an unselfconscious response to life, part of a live culture. For these children mystical realism and mythology is not separate from daily life. There is no dividing line.

‘Present Elements’

‘Here and Here’

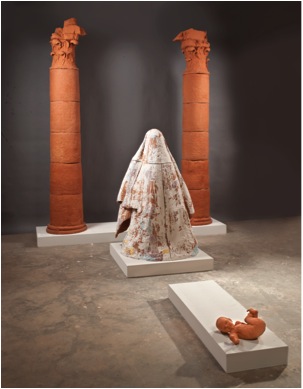

The use of the veil – how does this relate to reveal and conceal?

Metanarrative is a story within a story – I use it as a personal idiom suspended on the grid of an ancient tale or legend. In this work I use myth as the symbol of existence, of life itself and its essential meaning beyond the contingent occurrence of events.

The veiled woman is in stasis, the powerful emblems of national strength crumbling around her, unable to interpret the metaphor of rebirth and promise lying at her feet in the form of the infant child. The baby represents the woman’s progeny, our progeny, and is an embodiment of the future.

‘Metanarrative’

In complete contrast with the rest, this form is small, fragile, organic, moving, reaching outward. As a reconstruction of an idea of civilization Metanarrative suggests we conceive of cultural or historical values as constructs just as this scene is a construct that merges human figures with architectonic elements. More important, as personified by the child, is the living heritage we pass on, and a living culture, no matter how fragile or young. Any cultural dialogue, this sculptural installation Metanarrative implies, is a living dialogue with eternity.

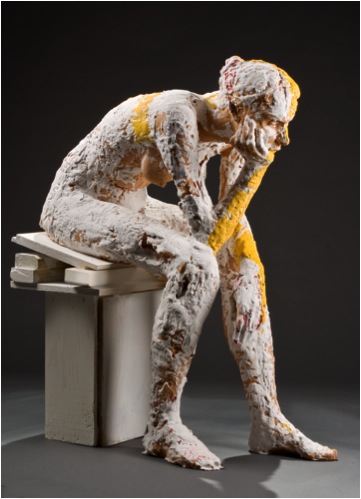

Can you discuss ‘Woman Drawing’ and how this evolved?

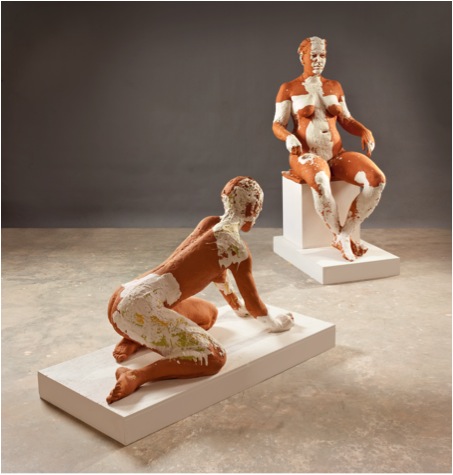

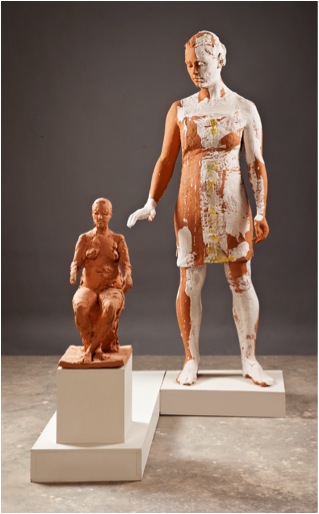

This sculpture builds a narrative using the physical communication between two figures. It is a metaphor for the process of making art – the reality of experience. The woman drawing is on her knees in front of the subject – the position describes the subjective attitude – an essential part of making an image of the live model – a reverence for the magnificence, complexity and diversity of the human form. Within this, there is no space for preconceived ideas or visual clichés on the part of the drawer – there is only receptive, careful observation and a delight in the resulting discoveries. In face of this – both figures are nude, exposed, one physically and the other intellectually. The dynamic tension, implicit in the way these two women interact, is defined by the self-assured confidence and passivity of the observed and the tight, energetic form of the observer.

‘Woman Drawing’

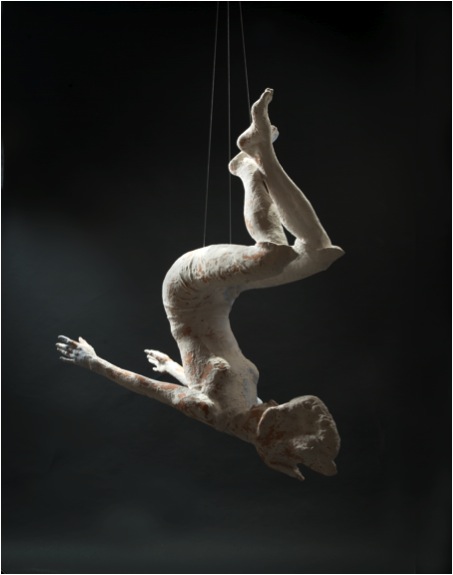

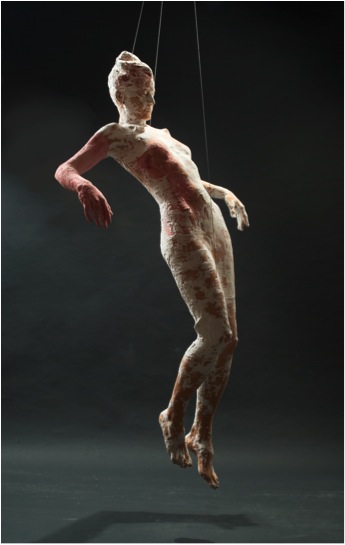

The immersion Series presents figures floating in suspended space. Discuss the inspiration for this series?

‘Immersion #15’

These sculptures are made from studies of my models underwater. Water refers to another dimension, an altered state of consciousness.

Figures in water react differently to sound, light, gravity, and movement. The human experience under water is cocoon-like – as if transformed back to the womb and in a private world of its own. The effect of gravity on the figure is diminished; there is free movement of the limbs and evidence of pressure from the surrounding water on clothing, hair and face

‘Immersion #17’

Suspended by cables in space the sculptures can be viewed from all angles – including underneath – freeing the work from the traditional pedestal, form, mass and weight of grounded sculpture.

‘Immersion #14’

Your art is influenced by many ancient works discuss the importance for you to look back to be able to move forward?

Whether in installation, performance, or sculpture, or any one of the many forms conceptual art takes, many artists today, including myself, believe that our rich visual heritage is a good source for reintroducing and advancing the language of art. From the dawn of time there has been the narrative: by the Shaman, by the Egyptian artists, the Chinese and European artists to tell their stories and to engage fully in the religious and spiritual world. I am adherent to the philosophy that the well-made object, by the artist, has an intrinsic value and is the preferred method for extending the language of art. In the process of making the sculpture – new things are discovered. This growth and transference cannot be accomplished by an intermediary. We often, now, search for inspiration in obscure influences rather than re-evaluating the accomplished examples achieved in the great periods of classical Rome, Egypt, Greece, the European Renaissance, and the Sung Dynasty in China. I understand that the past and present are always in flux. There are two ways of reconstructing the past – that of intuitively and mythically aims to define our emotions and experiences in view of the eternal concepts in ancient art. I walk a fine line between tradition and contemporaneity, I don’t re-create forms from the past, instead I reinvent and rephrase them using models from my own community on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia.

Is there a definite thread that connects you series?

Yes. The thread which connects all the series could best be described as “Metanarrative” because the five series have their initial concepts drawn from the great stories of our humanity, stories of myth, religion, ritual, and legend. At the same time these sculptures are equally derived from my immediate surroundings and experiences on Salt Spring Island. I am creating a story within a story so to speak. I’m rethinking how to tell the stories of today without overlooking the rich visual and conceptual history of the past.

‘Girl with Maquette Pan’

Can you explain the importance of your initial training in South Africa?

My art training began with one year of drawing. After this I chose sculpture as my major and ceramics as one of my subjects for my MFA. My ceramics lecturer, Hylton Nel, would show me a Chinese sculpture or bowl and simply say “look at this.” The language of art is visual. He taught me to build on that. Hylton was very connected and eclectic. There was always this excitement of discovery about him.

I watched the apparatus of state at a point of collapse. That is why I sought an even balance between beauty and truth. I needed to think that way in the studio in contrast to what I was experiencing out there in life. As a South African the issues of the day have influenced my artwork more than contemporary sculpture has. The experiential knowledge of living with such violence, poverty and suppression has and will always inform my artwork. It afforded my work a respect for context and truth and my work is different from my peers as a result.

As a child you were interested in ballet, do you think this was the initial link with your interest in the human body and the movement of the body to your work?

‘Batavia’

It’s the same thing, whether it is focusing and developing the movement of my human body or the clay figurative form to describe an attitude or tell a story, I learned through both disciplines the eloquence of the body and how receptive we are to interpreting even the smallest movement or positioning of the head or hand and, in antithesis, how responsive we are to weak, insincere or superficial rendering of the figurative form. The most important, early, lesson I learned from ballet was discipline itself. Staying with the idea and honing it for years until it says a little of the depth I see in nature.

How do you title your work?

These come from places in my past that I have loved or have been important to me in some way. They could be words lifted out of books I’ve read, concepts about the subject/content, or references to ancient political systems.

You have been very lucky with the beautiful catalogue – do you personally document your work?

Thank you. The photography of the artwork for the catalogue was done by a fellow islander – David Borrowman – and the rest were taken by Deon.

‘Tokai’

How important do you think it is for an artist’s actual daily feelings about their work to be documented for history?

My own daily feelings are irrelevant to my work and haven’t been influential, because, in the studio, there is no mystery of heightened awareness – only work and thought. There is the participation in the life of the subject, a view of the collective through the singular, within the silent dialogue between the model and myself. There is an ancient discipline of creating an artwork between artist and model and it is one which can never be fully explored, in face of the limitless diversity of the human form and psyche. The individual, her presence and attitude are life affirming. I also don’t think of my work in terms of individual, completed pieces. The ideas in one work will flow over into the next and inform the development there. All my work is one process that will never reach completion. It is this process that interests me. I’m satisfied with that.

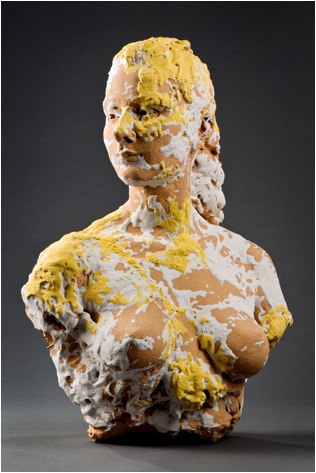

Can you discuss one of your much earlier works ‘Renata’ 1997 and the progression of you work?

The model for this sculpture was a transient young woman from the Czech Republic. She seemed to feed her mind only, not her body. She would save every penny, sleep in the bush, bathe in the lake, then buy expensive tickets to the opera. She embodied the resilience of her country, such a desire for cultural development in spite of difficult circumstances, and the lack of funds to support it. I admire her combination of strength in frailty. I choose models who embody qualities that are often overlooked in our fast paced culture. Character and intrinsic beauty is deep seated and it is a thrill to find where this is visible in the body of the person I’m looking at.

‘Only Now’

On a more simple level, can you discuss your studio space and what you require technically?

Deon and I each have a beautiful studio space. I don’t require much room for working in clay – but there is a good deal of equipment such as kiln, sand-blasting booth, compressor, dust extractor, fans, benches, banding wheels, boxes of clay, bags of sand and a hydraulic lift.

‘Kathy in her studio’

You have very good contact with curators, gallery directors and museum directors. Can you give some insight into how you have fostered these connections?

I was very fortunate to win the eye and support of Dr. Charles Mason. He has shown so much enthusiasm and respect for my work and, although he is no longer with the Gardiner Museum, this support together with countless months of assistance, support and advice from Deon, has led to the success of the exhibition Life and its future travels to other museums.

Kathy with ‘Coup d’Oeil

’

Contact Details:

Website: www.kathyventer.com

Email: dkventer@gmail.com

23 – 315 Upper Ganges Rd.,

Salt Spring Island, B.C.

V8K 2X4

Canada

Kathy Venter, Salt Spring Island, Canada

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September, 2013

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: