Kate Gorringe-Smith Printmaker

Migration is a huge backdrop to all your printmaking,

Comment on your background as a child of immigrants to Australia and how this has influenced your career and art.

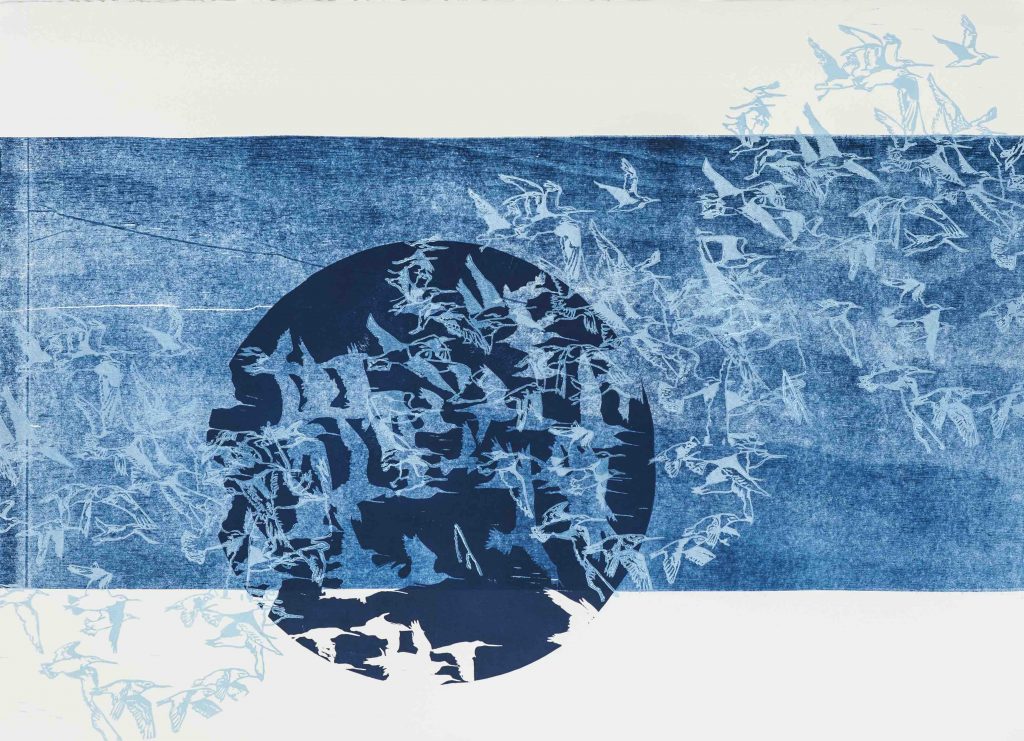

The Fossil Memory of the Sky (iii) 2012, Linocut and woodblock print, 56 x 67cm.

In 2009 my family and I returned home to Melbourne after three years in London. Our return was spurred by my father’s death; my mother needed me at home. We all had trouble reconnecting with our old lives. My parents, ten pound poms, migrated to Australia in 1966, the year I was born. Without Dad, it was suddenly clear that it was not so much Australia that was Mum’s home, as my father himself. Without him to anchor her, her heartland reverted to England.

I began to use migratory shorebirds in my work for my first solo show in 2010, in particular the Bar-tailed Godwit. These birds travel annually from Australia, where they avoid the harsh northern winter, to Siberia, where they breed. Ever restless, they never settle. One can interpret neither destination as their true home, or both. Our brief period overseas, coupled with my bereaved mother’s stories, gave me an insight into the tragic and hopeful world of migration and resettlement. The birds provided the perfect metaphor.

Red Suitcase, 2011, Linocut and collage 76 x 56cm.

As well as embodying this deep sadness, shorebirds also carry the hope of overcoming amazing odds as they travel annually across the globe, traversing seas and continents. These tiny birds can fly for nine days straight without stopping to rest or eat; they can navigate an entire ocean without any landmarks; they can fly in their lifetime further than from the earth to the moon, and they link 23 countries with their journeys.

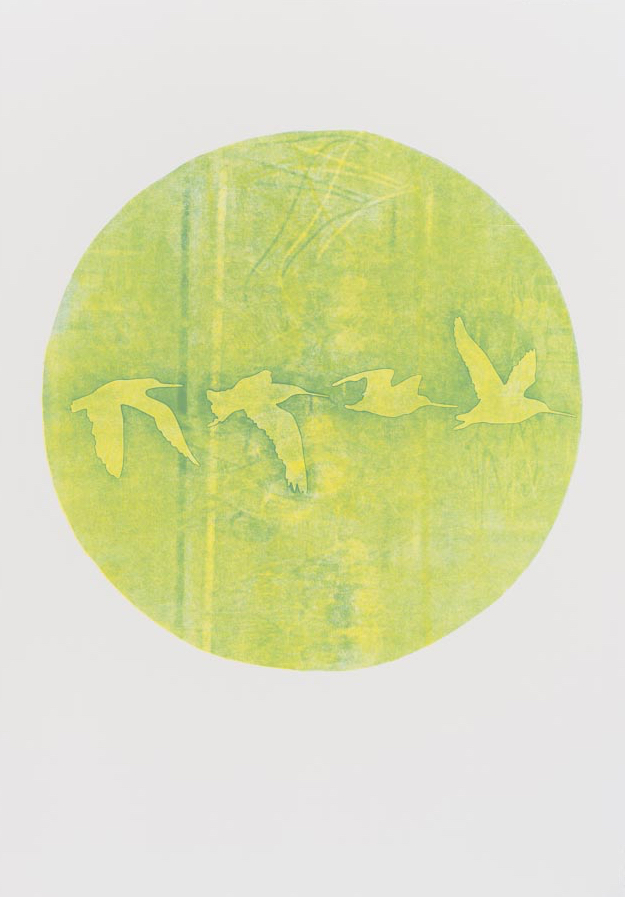

Fly by Night, 2012, Linocut, 32 x 27.5cm.

Since this first exhibition in 2010 I have continued to use migratory shorebirds in my work both as metaphor and as themselves. I have since discovered that they are our most endangered group of birds but sadly, in general, are very poorly known by the wider population despite ours being a beach culture. It has become a bit of a mission to try and bring these amazing birds and their plight to light.

Discuss how you have been influenced by your time with Birdlife Australia.

I had a great six years in the 1990s working for Birdlife Australia, or the Royal Australasain Ornithologists Union as it was back then, as a scientific editor. My first position was as Assistant Editor working of the mighty seven-volume tome, the Handbook of New Zealand, and Australasain Birds (or HANZAB for short). I later worked as editor of the RAOU’s membership magazine, ‘Wingspan’. I also did some illustration work for them on the side, and while working for the RAOU I did my degree at RMIT in printmaking.

An Instinct for Mapping, Stenciled woodblock monoprint, 76 x 100cm.

Working for the RAOU was a huge influence on my life – not only from the point of view of learning so much about birds, but also working for an NGO full of passionate and knowledgeable people who had great integrity to the organization and the environment.

These days I am so thankful to have worked there as it provides me with a great resource to support the work I am trying to do with communities and artists. I am on my third and biggest group art project based around migratory shorebirds, and my contacts through Birdlife are so generous with their knowledge and time – they are a great support to my work. Also, The Flyway Print Exchange and my current project, the Overwintering Project, both have a fundraising aspect built into them and having worked for Birdlife I am happy to be able to send the funds raised to their shorebird conservation projects knowing the money will be well spent. I admire their employees and volunteers so much. It is a connection I treasure.

New Constellations, 2015, Hand coloured linocut, 56 x 76cm.

This print was accepted into the 2015 Silk Cut Linocut awards

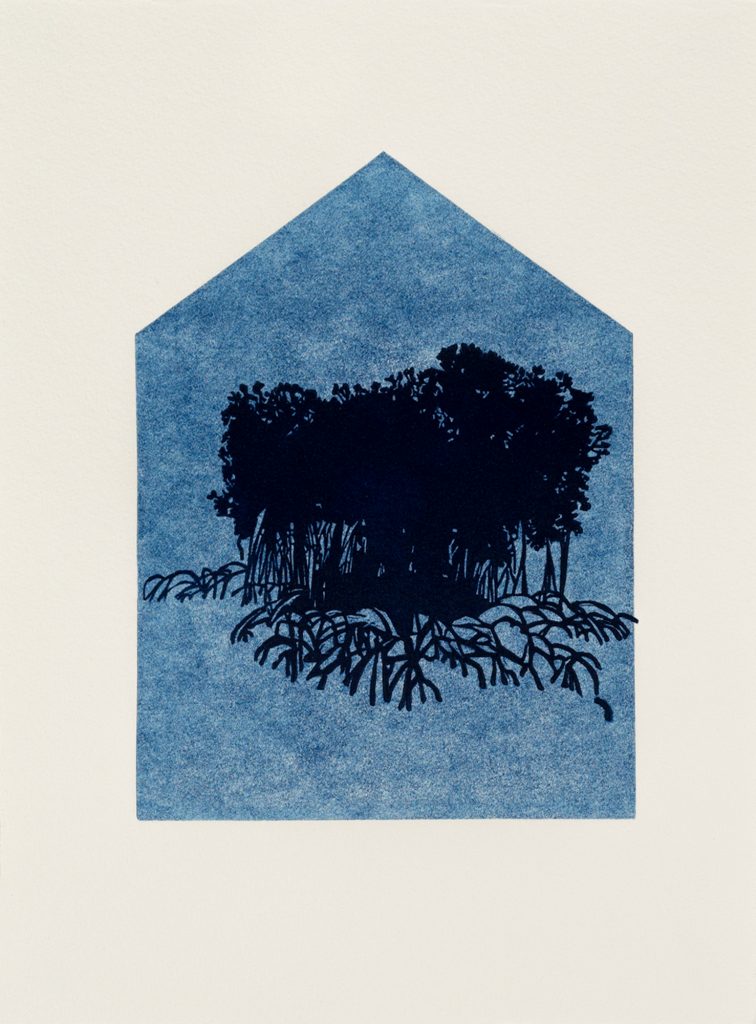

Take, ‘Notations of Home : Westernport White Mangrove’ discuss.

‘Notions of Home: Westernport White Mangrove’ is part of a series of works based on species found in the Western Port Ramsar site, my chosen research site for the Overwintering Project (The Ramsar Convention is an international convention created in the 1970s to protect internationally significant wetlands www.ramsar.org). It is a linocut.

Notions of Home: Western Port White Mangrove, 2018 Linocut, 17 x 13cm.

The house shape is a ghosted linocut (so it is the second print without re-inking the linocut – hence it is a softer shade of Prussian Blue), and the mangrove silhouette is also a linocut printed over the ‘ghost’ house. The print is quite small, only 17 cm high x 13 cm wide. Blue is my favourite colour – I find it hard to abandon. But it is also the colour of the water, the sky – life. The idea behind the print (and also The Overwintering Project – more on that later!) is that if we extend our idea of home to include our environment we have to accept responsibility for it. A couple of years ago I came across the following quotation by Wanta Jampijinpa, a Warlpiri Elder: ‘Knowing your animals and plants, your environment, is knowing your home and yourself.’ This statement articulates my intentions beautifully. The Western Port White Mangrove is, I believe, the most southerly occurring mangrove and of course mangroves are nurseries and shelters for many animal species.

Your art cannot be discussed without talking about your involvement with shorebirds – explain.

In answer to your first question I wrote how I first came to use migratory shorebirds in my work, as a metaphor for the longing a migrant feels for home. Since then I have researched and thought about these birds a lot, and they have come to mean a great deal to me.

Migratory shorebirds connect the world. Every year they migrate from the shores of Australia and New Zealand to their breeding grounds above the Arctic Circle in Siberia and Alaska. The remarkable annual circuit that they fly is called the East Asian-Australasian Flyway and it passes through 23 countries. The pathways of their migrations bind skies, land and sea into a meaningful whole. Their journeys connect us through time and space, as they have been flying between the poles for more years than humans have walked the earth.

I have come to believe that migratory shorebirds and the Flyways are important ideas for our time. They challenge our notions of what is precious – they are small, their plumage is modest, they do not sing and their habitat is often unremarkable. But they fly unimaginable distances, their biology is so finely tuned that they can fly eight days and nights without stopping to eat or drink, they can navigate featureless oceans to find the same tiny stretch of beach, and return to it, year after year after year. And, in an age where human migration is often viewed as a threat to borders and resources, these tiny birds also remind us that we are globally interdependent in a multitude of complex, subtle and ancient ways. But they are also our most endangered, and possibly least known, group of birds.

Birds are bio-indicators. This is a bloodless term meaning that the presence of birds indicates a healthy environment. If shorebirds continue to decline at their current rate, and some species have declined by 80% over the last 30 years, it also means that the global environment of the Flyway is being seriously degraded. This of course also affects our health, wellbeing and ultimate survival. Looking after migratory shorebirds and the Flyway is another way of looking after ourselves. It is urgent and it is vital. I would like to think we are doing it for them and all the other living things that depend on the global ecology, not only to save ourselves.

Briefly explain

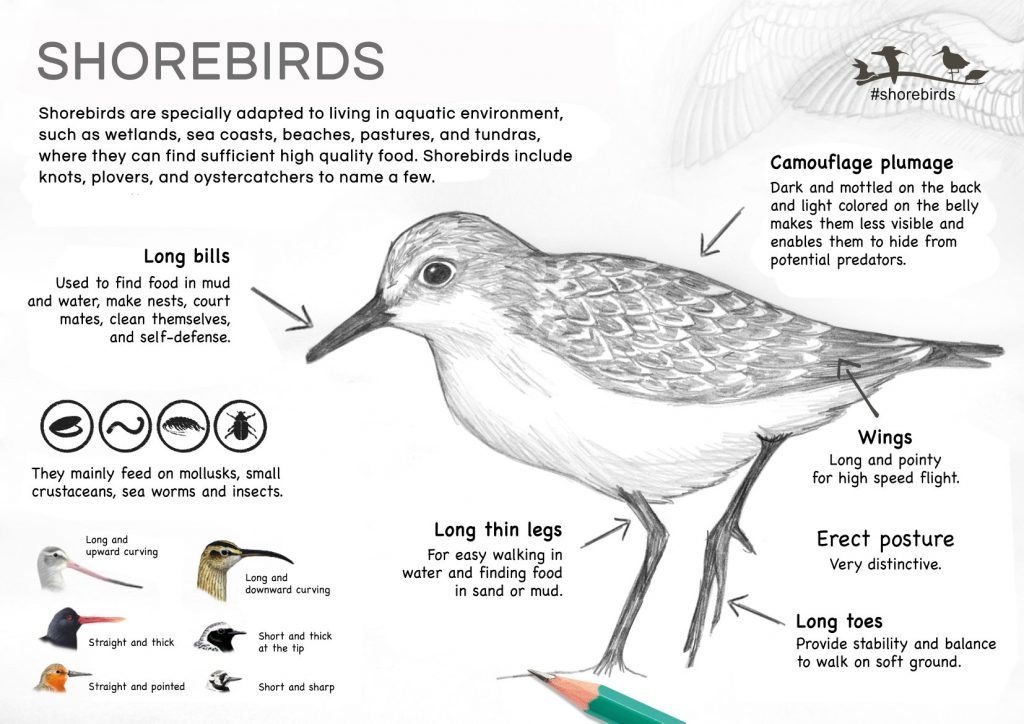

What are shorebirds?

Shorebird, ID

Godwits, sandpipers, stints, plovers, whimbrels, curlews, snipe…we have thirty-six species of migratory shorebird that spend October to May on the coast of Australia and New Zealand. Come autumn, they head north. Their destination is their breeding grounds in northern China, Mongolia, Siberia and Alaska. Once they have bred they will head back south, completing an annual circuit of roughly 25,000 km. Over their lifetimes many of these birds, having completed this journey every year of their adult lives, will have flown more miles than from the earth to the moon.

Red-Necked Stint Photo by Dan Weller

‘Shorebirds’ is the US term for these birds. In the UK they are called waders, and here in Australia we use both terms. They generally live on the shore, hence the name, and are small to medium sized with longish bills and legs. The shape and size of their bill denotes the prey they eat. They forage on the mudflats, following the tide out daily to get their required food to build up for the next migration. As the tide comes in they come in to shore to roost. They are incredibly well camouflaged. They don’t have webbed feet.

They really do have both a literal and metaphorical visibility problem. Friends of mine who have literally spent their entire childhoods on the beach have never noticed them. They are incredibly well camouflaged, but also when the tide is out they go out with it – maximizing their foraging time to fuel their unbelievable migrations. Next time you are on a beach with mudflats, looks for tiny brown birds, often in a flock, that make the regular silver gulls look huge. They will often lift as a flock when spooked by a dog, flying as one, glittering in the sunshine.

The journeys they take.

Map of East Asian- Australasian Flyway

No-one really knows why shorebirds make the migrations that they do, except that the arctic has an incredible amount of available food in its short summer, and similarly our southern beaches provide a warm and food-rich haven whole the arctic is engulfed in ice and snow. But why these journeys began is a mystery. An amazing mystery! The circuit of the Flyway is 25,000 km long and over its lifetime of migrations one of these shorebirds, which are quite long-lived, will travel a distance further than from the earth to the moon and back!

Navigation is another mystery, but scientists have evidence that shorebirds can detect the earth’s magnetic field, which would help with orientation. It is also thought that they may us the stars to navigate.

Bird watching at Stockyard Point, on the Mornington Peninsula, Victorian Wader Studies Group

From tagging birds we also know that many species are incredibly site faithful, which means that they will return to the same stretch of beach every summer. We don’t yet know whether the young of a bird will return to the same stretch of beach as its parent, but I believe research is being done with bird DNA to see if this is the case.

What is the East Asian – Australasian Flyway?

The East Asian-Australasian Flyway describes the route these birds fly annually from Australia and New Zealand to arctic Siberia and Alaska. It is one of eight Flyways that encircles the globe, and links 23 countries, each of which plays a part in providing habitat for these birds to overwinter, stopover or breed. The countries are: USA (Alaska); Russia (Siberia); Mongolia; China; North Korea; South Korea; Japan; the Philippines; Vietnam; Laos; Thailand; Cambodia; Myanmar; Bangladesh; India; Malaysia; Singapore; Brunei; Indonesia; Timor; Papua New Guinea; Australia and New Zealand. We are all links in the chain that protects the survival of these birds. There is an organisation, the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership which works across borders for the conservation of our migratory birds.

The threat you are trying to highlight through exhibitions.

Of the eight global Flyways, ours is the most highly populated (by two thirds of the world’s population), and includes countries with many of the world’s fastest growing economies. These factors, coupled with the fact that wetlands are disappearing at a rate three times faster than forests (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 27 Sept. 2018), put considerable pressure on migratory shorebird habitat. Migratory shorebirds depend on mudflats and intertidal zones, much of which has been reclaimed along the Flyway for industrial, recreational or residential purposes. Over the last 30 years these pressures, particularly in the region of the Yellow Sea – a critically important site for shorebirds to rest and refuel during their migrations – have seen some species decline by 80%. They are also at risk from climate change which has already been detected to be ‘shifting; the arctic seasons so the birds are not getting as much feeding time during their arctic breeding period.

Shorebirds at Stockton Sandspit, Newcastle, NSW, Australia, photo Juliana Ford

The best thing for us to do to help our migratory shorebirds is to join an organisation like BirdLife and put money toward shorebird conservation, and keep our dogs tethered on the beach so they don’t disturb feeding shorebirds. Disturbance by dogs may seem momentary, but remember these birds’ biology has become so finely tuned over thousands of years of evolution and if they are disturbed by humans or dogs they may not get enough food to fuel their migrations. When you are talking about 28 gram birds to miss out on these few extra grams of fat is highly dangerous.

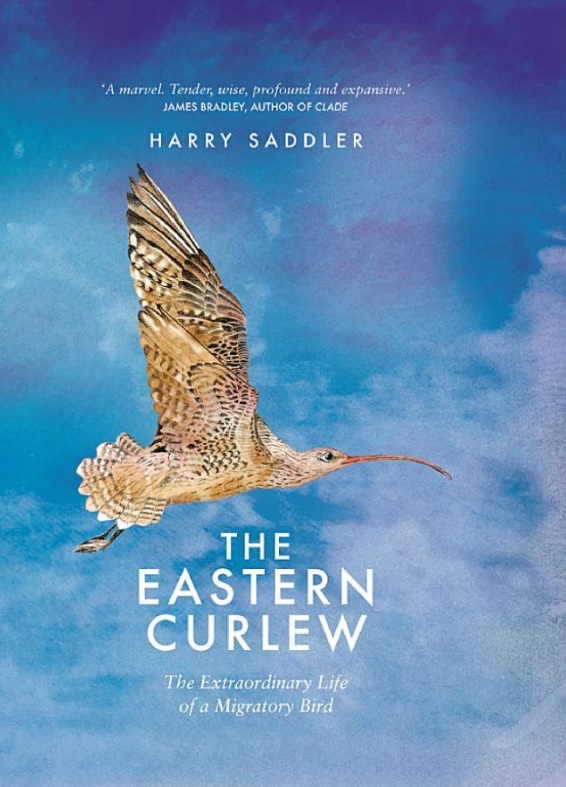

I discovered so much by reading ‘The Eastern Curlew’ by Harry Saddler, can you give a short review of the book and your personal relationship?

‘More than any other group of animal, birds carry the weight of our metaphors. They fly heavy with meaning.’ (p. 76)

Harry Saddler has written a very special book in The Eastern Curlew, a wonderful heartfelt blend of scientific fact, Flyway travelogue and personal insight. It is an incredibly thoughtful and well-researched book that paints a vivid picture of the most endangered of our migratory shorebirds. I learned a lot from the book, but the one thing that was really impressed upon me was how much of a little machine this bird is and how every minute of its life feeds into maintaining these epic migrations. There is no room for chance – they eat, they rest, they watch the weather to choose their moment and they fly, breed, then fly again.

I met Harry when he was researching his book – he had been asked to review my first major migratory shorebird project, ‘The Flyway Print Exchange’ which was on exhibition at Melbourne’s Immigration Museum (http://rightnow.org.au/review-3/why-shorebirds-in-the-immigration-museum/) and so contacted me to chat about shorebirds when he was researching his book.. We are still friends, and he took me and my son to French Island in search of Eastern Curlews last summer. Sadly we only spotted them in flight so didn’t get a good look, but it was a lovely trip.

The Flyway Print Exchange

Travellers

How did Flyway Print Exchange exhibitions come about?

The Flyway Print Exchange was the first major group art project I ever undertook. The idea of trying to involve artists from all along the Flyway in a print exchange, and then actually sending the prints along the Flyway and back – to follow the birds’ route of migration – just came to me and then seemed too good an idea not to pursue! I ran the idea by Dr Golo Maurer, who at that stage was the head of Shorebirds 2020, BirdLife Australia’s main shorebird conservation program. He encouraged me and somehow that was enough to make me just jump in!

Starmap, 2014, Etching and linocut, 26 x 26cm

My hope for the project was to make people really understand the reality of these birds’ migrations – the distances they travel and the perils they face. It is one thing to know a fact in a cerebral way, it is another thing to believe something viscerally and in your heart. I think that art can move a person from knowing to believing, and this is what I hoped to achieve, at least for some, with the Flyway Print Exchange.

To finance the project I was lucky to receive funding from the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board in SA, and a grant for Melbourne Water. The NRMA funding helped me stage the first FPE exhibition as part of the 2014 Adelaide OzAsia festival which celebrates the links between Australia and Asia, and the Melbourne Water grant supported the first Melbourne exhibition at No Vacancy, a small gallery in Melbourne’s Federation Square in October 2014.

How many artists were involved and how did they come on board?

My plan was to find 20 artists from as many Flyway countries as possible to participate in a print exchange inspired by the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. I put out calls through both printmaking and shorebird networks – and was astonished by the response I received. It was fabulous! And so exciting to hear from artists all over the world!

I started by emailing as many print facilities and workshops in Flyway countries as I could find. Some responded; some didn’t. There were interesting hurdles to overcome! For example, to contact printmakers in China, I emailed Red Gate Gallery in Beijing, a gallery founded by Australians, to ask for advice. They suggested I have the project description translated into Chinese, which I did, and subsequently had many expressions of interest! I had the email address of a Siberian ornithologist who I hoped might help me find local printmakers, but unfortunately she was in the field when I needed to find my artists so I had no luck there.

In the end I had twenty artists involved, from nine Flyway countries: New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, India, Japan, South Korea, China and the USA (Alaska). They are Amanda O’Sullivan, Helen Kocis-Edwards, Vida Pearson, Alexis Beckett, Violet Hammer, Sharon Keighran, Gret Mingundoo Allwood, Syarhizal Pahlevi, Feng Jianming, Ni Jianming, Hyun Tae Lee, Kyoko Imazu, Garry Kaulitz, Edwin Mighell, Cia Xiao Hua, Celia Walker, Tham Pui San, Radhika Gupta and Kavita Shah.

I’ll always be grateful to these artists for their trust and generosity. Each artist made a new print for the project and editioned it 30 times – and most of the artists did this without even knowing who I was. Thanks to funding I was able to provide paper for the editioning, although Ni Jianming in China used his own paper as the heavy Hahnmuhle I provided did not suit his print medium. Each artist also received a full set of the prints.

The result of the exchange is manifold. It is a literal exchange – with the prints changing hands and being shared – but it is also an exchange of ideas and inspiration. Our disparate group of artists – varying in age and experience, not to mention culture and background – which may never gather together in person, is now bound by this exchange of work. A small community has been created around the works and around the Flyway itself.

How many places did the exhibition go to?

To date there have been over 20 Flyway Print Exchange exhibitions in every state and territory of Australia except Tasmania and Canberra, as well as in New Zealand, Indonesia, Singapore and Hong Kong.

How far were some of the exhibitions?

Hong Kong is the farthest destination to which the exhibition has travelled.

Explain the story behind the sending of the second print by mail and how did they fair in comparison to the flight path of the birds.

Xixe Xi City, 2014 (Habitat capital) Woodcut, water, printing, 26 x26 cm. (paper size) by Ni Jianming

Flyway Print Exchange exhibitions consist of two sets of prints – one set is pristine, while the other set have been posted along the Flyway and back, from Melbourne to New Zealand, to Singapore, to Alaska and then back to Melbourne. The prints returned home weathered and crumpled, marked by addresses, postmarks and stamps. In the gallery space they stand in for the birds themselves, bearing witness to the physical journey that the Flyway defines.

The Overwinter Project

Give brief history of these exhibitions.

The Overwintering Project is my current project. It is designed to connect artists around Australia and New Zealand with their local migratory shorebird habitat. Conservation campaigns are still usually run with a ‘heroic’ species as the target for conservation. This is probably because it is easier to make people relate to a cute animal, but it doesn’t always help in getting the message across that to save species we need to save habitat, and also that habitat incorporates entire complex systems that include plants, animals, and inanimate elements such as hydrology and geology. So in the Overwintering project I am inviting artists to go out into their local shorebird habitat, preferably with a shorebird or local expert, to see the birds and then to make a work in response to any aspect of that habitat that inspires them. In this way I hope the project will also promote a recognition of the value of biodiversity and of course, because the birds migrate, how this local habitat links us directly into a global ecology.

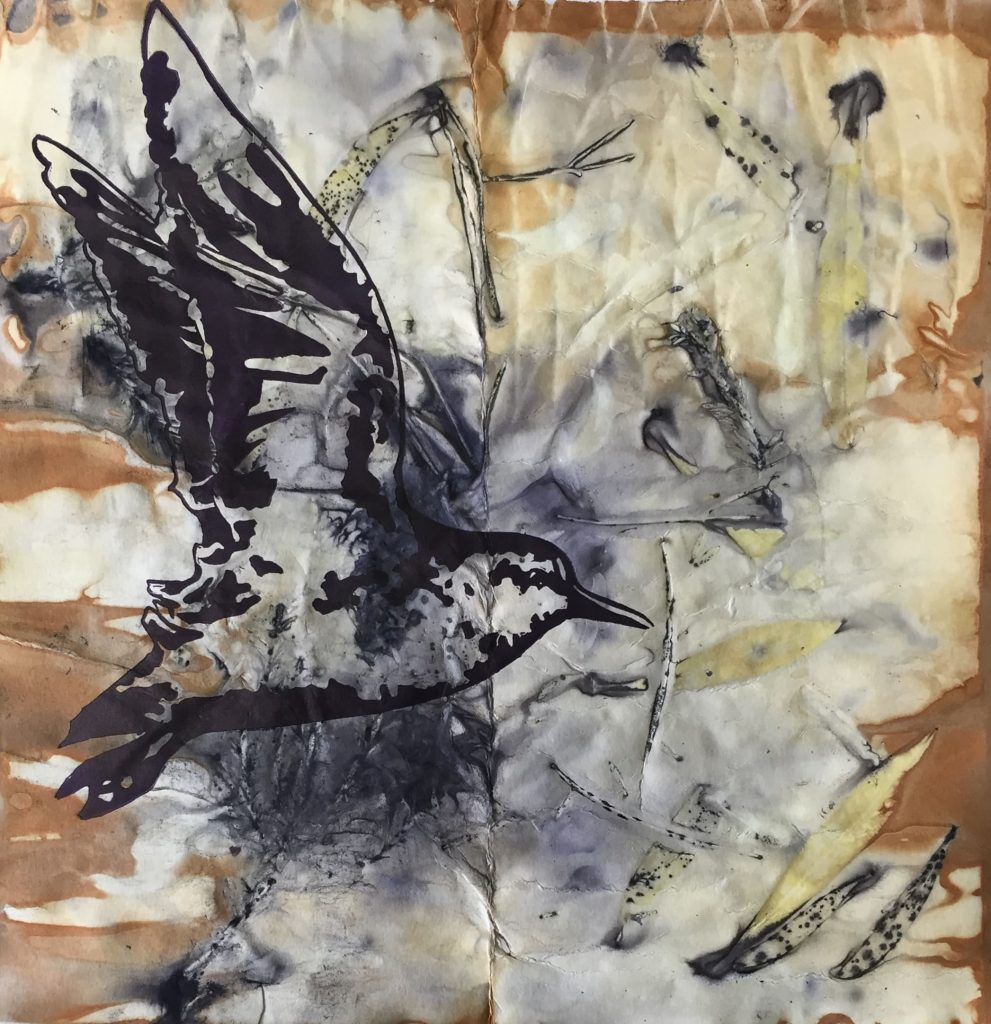

Tidal Fugue, 2018, Linocut on eco-printed paper, unique state, 60 x 90cm.

I launched the project in June 2017 and so far there have been 15 exhibitions in NSW, Victoria, Tasmania, Queensland and South Australia. Another 13 or so are already planned reaching into 2021, including major exhibitions which will include the Overwintering Project Print Portfolio (this consists of prints donated by artists in response to open calls) at Charles Darwin Uni in the NT, Mandurah PAC in WA, Coffs Harbour Regional Art Gallery in NSW, the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery in Victoria and the Burnie Regional Art gallery in Tasmania. Over 150 artists have joined the project, both by contributing works to the Print Portfolio or by holding their own local exhibitions. We have so far raised $10,000 for BirdLlife Australia’s migratory shorebird research programs from the sale of prints!

How can others become involved in this project?

Artists who work in print media can send me prints to join the project’s core (the bit I am in change of: two of the same print, 28 x 28 cm, one to exhibit and one to sell – but please email me first for details) – the Overwintering Project Print Portfolio, but anyone anywhere working in any medium can hold their own Overwintering Project exhibition independently as long as the project’s aims and parameters are adhered to. Just email me and we can go from there! I can help you find your local migratory shorebird habitat and local shorebird experts, and will help publicise your event or exhibition through the project website, newsletter and social media. There are also ways for schools and community groups to get involved.

Altona Stint, 2019, Linocut on eco-printed paper, unique state, 28 x 28cm.

Comment on the quote, ‘ Knowledge bestows ownership: uniqueness bestows value.’

A few years ago I was invited to be in a print exchange about Portland, a small historic town on Victoria’s western coast. I’d spent a bit of time there for various reasons – travelling between there and Mount Gambier, which lies of the other side of the SA border. My research into both areas, and the Victorian Great Basalt Plain that stretches from the SA border to inner city Melbourne, made me realise that every place is environmentally unique. Not just remote, pristine places, but local urban areas have unique geologies and ecologies and associations of species. So when I was writing the Project Description for the Overwintering Project, which is designed to try and generate a genuine connection between artists and their local migratory shorebird habitat, I was thinking about what it is that makes us value a place. So I wrote this phrase to try and encapsulate what it is that makes us value and feel ownership (and therefore responsibility) for a place.

‘ Knowledge bestows ownership: uniqueness bestows value.’

Contact details:

Kte Gorringe-Smith

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June 2019

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: