Joan Waters Sculptor - Arizona, USA

You began your art training in 1976 when did the use of welded steel begin and how?

Some background—I was born in England, and grew up in Baltimore, Maryland, where I earned my BFA at MICA, Maryland Institute College of Art (a combined major—painting/drawing/printmaking/sculpture, summa cum laude). I moved to Phoenix in 1989, and had my own graphic design business. After 9/11, when the economy suffered, my design business slowed and I decided to get a body of work together and start exhibiting my paintings.

I enrolled in a Basic Welding class at Mesa Community College. I had always liked making designs with positive and negative shapes, and had been cutting them out of various types of paper and board over the years, though I was frustrated with how flimsy and delicate they were. I didn’t really respond to metal, until we started using the plasma cutter, and that’s when the light went on. Suddenly I was able to cut shapes out of thick sheets of steel with this 10,000-degree torch as if it were butter. And they were substantial and durable, unlike the paper cutouts. Because I’d been drawing my whole life, the lines I cut were as natural as making a line drawing with a pencil. For the next couple years, I focused on cut out positive and negative shapes with colored patinas, and gradually started to understand how to construct and weld three-dimensional forms.

I use industrial materials and processes to re-interpret conventional art practices. Large sheets of industrial, cold rolled steel, angle iron and solid rod are cut, hammered, welded and ground to become layered, organic forms. Although I work in a wide range of mediums, at the core I see it all as drawing and painting. For example, I’m using the mig welder and plasma cutter to “draw” on the metal, “erase” with the angle grinder, and “paint” with patinas on layered steel sculptures.

The experience of working in different mediums, say painting and metal, is that I can take a discovery in one medium and explore it in another. Consciously avoiding getting locked in to knowing the “right” way to do things, keeps the exploration process open and inventive.

As soon as you adopt the perspective that you know the answer, you’ve lost the element of exploration that keeps the imagination alive.

The Arizona Arts Commission has been very generous in providing Professional Development grants to you, discuss.

The advantage of these grants over a series of years. How the terms and conditions of the grants have influenced the direction of your work.

These are supplemental grants that support learning and development activities–I’ve used several of them to assist in attending sculpture and metal working conferences around the country. Because the grants supplement the artist’s own funds, they support the artist’s own commitment and provide a monetary boost. There’s no restriction on the work. I feel they’ve helped me broaden my perspective by attending these conferences and meeting artists from other parts of the world. It’s an honor to receive them, and the selection process also brings credibility to the work I’m doing.

Your comment, “I do know the completed work sings or hums – there is a vibration that comes out of it.” Comment on this.

Explain the welding lines… Technique

Effect that it produces on your work

This quote was from my exhibition “Beyond the Shiny Metal Object: Reflecting on the Shadow’s Light”. These works were large steel sheets that I welded series of lines, patterns of concentric circles and lines onto. My process was to first cut and grind the entire front and back of the steel sheet, then make all the welded patterns in one big session. As the welding progresses, the heat collects in the steel so it is quite hot—it’s hard to work close to it for so long. Since I’m wearing a dark welding hood, my field of vision is very small—it’s like driving down a pitch black road at 60 miles per hour with a flashlight guiding the way. I’m relying on years of drawing practice to control my hand and guide the line. Where the patterns are concentric circles, I do it in one shot, and there is no going back to make corrections if I mess up the welding.

As the welded panel cools, it contracts and starts to curve and become concave, depending on how the welding was done. After much cleaning and grinding I apply patinas and then there is further finishing and refining with air tools, wire brush, etc. Both in the working process, and when the piece is finished, there is visually and acoustically an effect of sound or vibration being directed back towards the viewer from the concave surface of the steel.

You use energy patterns in many of your pieces expand on how and where you find the patterns?

I think these suggest energy patterns.

According to quantum mechanics, what we see as ‘solid objects’ are actually comprised of particles, discrete packets of energy with wave-like properties.

This body of work explores the similarities in these wave-like, energy patterns that are found in many different types of living beings and situations in nature. Ripples of water in a river, raindrops falling into puddles, growth rings of trees, vibrations, sound waves, and galaxies in outer space, are some of the forms suggested by these drawings of radiating lines and arcs. The process of making these pieces deliberately includes several elements of uncertainty and lack of conscious control, so that natural forces and patterns may become part of the evolution of each piece.

Eddies in the Stream, welded steelwith patinas, clar powder coating 17 x 57 x 3 In.

As the welded patterns overlap and run off the edges of the steel, it creates the impression that the piece of steel doesn’t contain the waves of energy, as much as it functions as a window which allows us to view these energy patterns found in the ‘objects’ around us.

Many of your pieces are designed to be seen from all angles discuss this.

In painting, there is a practice of viewing a work in progress from different directions, to make sure the composition is strong and well balanced. I often employ this practice in creating the work, but I have taken it a step further, and let it influence how the finished work is viewed. By choosing to hang a sculpture horizontally or vertically, the viewer is able to participate and engage with the work over time. I think what makes a piece worthwhile is if the viewer is able to engage with the work, and explore their own questions in it. Many of the compositions reference patterns and forms found in nature, and it is interesting to see the universality of these forms which are found in vertical and horizontal configurations.

Steel Origami, welded steel, patinas, paint.

‘Passage’ is an acrylic on canvas while ‘Mariposa: Scaffolding for Growth’ is welded steel can you discuss the comparisons that can be found in both pieces?

Thank you for making the connection between these two.

Passage, Acrylic on Canvas, 18 x 24in

They were not created concurrently, so I was surprised to discover the similarities in the two works-I believe the painting came first. Both works suggest these forms and light in space, looking through scalloped openings, and a sense of mystery, of something being revealed over time as the eye discovers new patterns and shapes. The sculpture has the added dimension and hidden “twigs” structure behind the front pieces, which invites exploration of the colors and shapes in its shadows.

Mariposa: Scaffolding for Growth, welded steel, patinas, 29 x 19, 6in

You have been influenced by African masks, discuss this in relations to your work ‘Mariposa: Mask’.

Maripasa: Mask, welded steel with patinas, clear powder coating 20 x17 x 6 inches

Mariposa is butterfly in Spanish, and I prefer the Spanish title because it is free of the preconceptions we have with the word ‘butterfly’. The Mariposa series was influenced by Rorschach inkblots, where there is a mirror image coming off a central axis, and the viewer is left to create their own interpretation. This piece conceals a hidden layer within, which is also the hanging mechanism. When viewed from the back, the interior is smooth and finished, like a mask interior, and visually interesting in its own way. I called it mask because it seems to hide a second identity, the elements which are behind it, which is the ‘shadow’ of its outer presence. It is thick steel with welded markings. the edges are beveled and shaped with the grinder to reflect light on the different angles and create a sense of movement.

Light plays a part I your work ‘Shadow Branches’ and ‘Steel Origami’, these are both very different but both use light to complete the work, discuss.

Because we have so much sunshine here in Phoenix, I’m often thinking of light and shadow as important visual elements in my work. ‘Shadow Branches’ , made of hammered steel rods, float and intertwine in space, and cast intriguing layers of shadows on surrounding walls. These are constructed out of round steel rod which is hammered and bent. The individual branches can be configured into constructions from a few branches to entire walls. When the light is directed on them, the shadows become a dynamic element that twill change as the light changes.

Dendrites – Shadow Branches, welded steel, acrylic paint

‘Steel Origami’ uses thin sheets of steel with paint and patinas. I create folded, constructions, as if suggesting folded paper. When lit from within, the cut out areas throw shapes of light onto the wall.

‘Sammamish Totem’ has a very strong natural element expand on this.

SammamishTotem, 18 x 16 x 82 in

‘Sammamish Totem’ was inspired by some totems I’d made with Arizona desert motifs, but this one, a commission for a couple who live outside Seattle, Washington, suggests plants and animals that are indigenous to that region, known for its old growth forests, salmon and rainy climate. Ferns, birds, fish, a nest, mushrooms and viney undergrowth become totemic elements to the piece. It was built to enliven their back patio, set the forest trees.

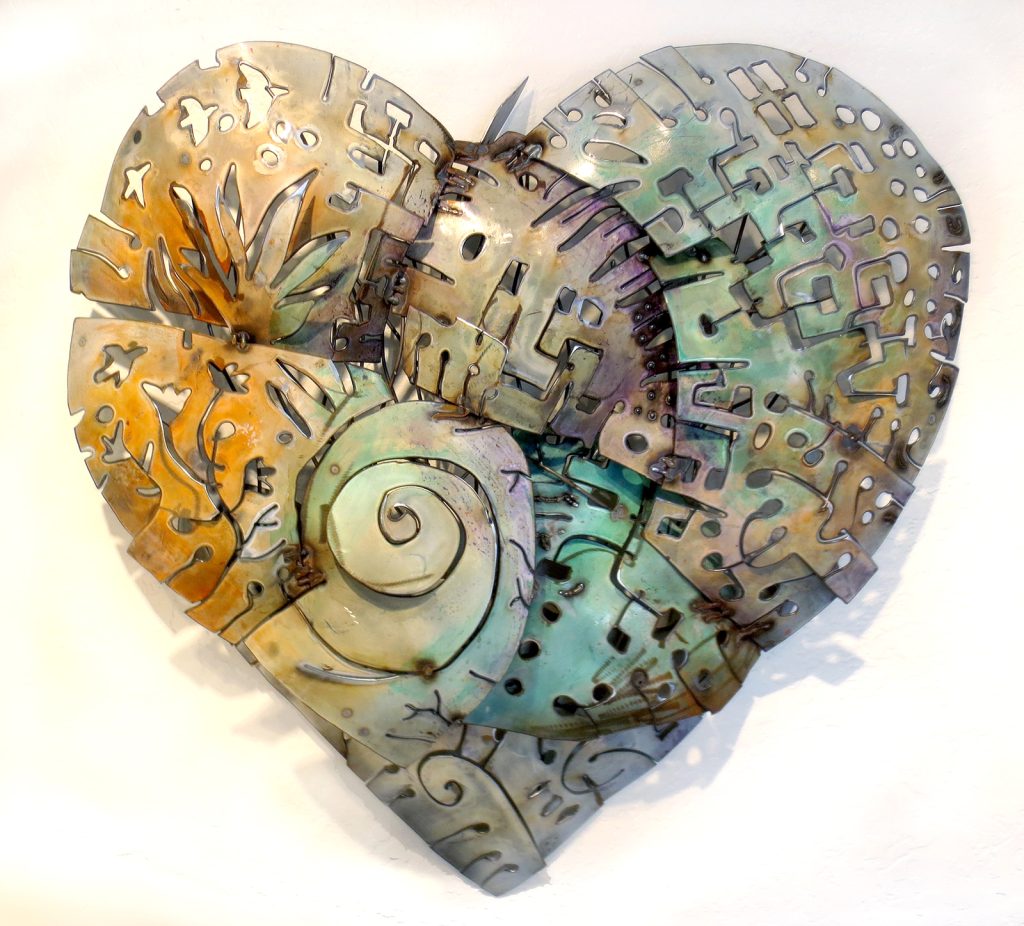

Size is shown on your ‘Desert Heart’ pieces expand on both in relationship to size.

The smaller ‘Desert Heart’ was created first. It got its name from the curious dichotomy of living things here in the Sonoran desert—they can be quite alive, but appear dormant or dead at times. After a rain, they bloom with color and seem to spring to life. The duality of nature—its power to destroy as well as create—becomes part of each piece through the extreme amount of deconstruction, cutting up and taking apart, that is necessary before the work can be re-ordered as a unified organic presence.

Desert Heart, with LED lighting

In making this, I was curious to see how much of the steel I could cut and remove, which made the piece seem very fragile. I then hammered and bent it, curving it around into a dimensional form, and welded it in place. I took care to scale it up carefully, and add more detail so the larger version had the same feeling to it. The large version was donated to a fundraiser at the Desert Botanical Garden, and had an LED light rope behind it with changing colored lights, for a very dramatic effect.

Desert Heart, welded steel with patinas, 30 x 30 x 7 in.

Explain the process you have used in ‘Calligraphy in Space’.

Technique / Colours / Sizes

This series translates the energy of making a calligraphic drawing into the form of welded steel sculpture. Drawing, based on observation of objects in the environment, and the process of making marks and ephemeral gesture drawings, becomes the foundation for entirely new objects in space.

Calligraphy In Space, Hand cut steel with red powder coating,

The beginning is a sketch or vigorous gesture drawing with brush and colored patinas onto a large sheet of heated industrial steel. I trace around the marks and cut out freehand with a 10,000-degree plasma cutter. Through the process of grinding, welding, and layering the material with hidden spaces, I am able to re-configure the brush strokes into new abstract three-dimensional objects which suggest the dynamic energy and physicality of the original drawings. Some of the heat marks from the cutting remain in the colored patinas, which adds more depth to each work.

Calligraphy In Space; Black, welded steel with patinas, 40 x 37 x 3 In.

‘Desert Towers’ was a commission for a garden, discuss the commission and also working with both the landscape architect, homeowner and your own personal response to the pieces. How you were all able to combine and come to such a positive finished commission?

‘Desert Towers’ is a great example of the synergistic process of working on a commissioned project (if all goes well).

Desert Towers, Commission

I met the client at a studio tour where I was exhibiting, and as it was early in my working with steel, I wasn’t quite sure what I would design for him. He liked my work, and the positive and negative shapes cut out of steel. At first, the client was thinking of stone filled gabillons, which I’m glad we didn’t do, because he would not have been able to take them when he moved!

Desert Towers

I did a number of site visits, took photographs, and made sketches and some models which were part of the dialog and process with the client. A landscape architect wasn’t involved. The goal was to add character to the pool area, including at night, provide visual screening from the golf course, and increase privacy along the neighbor’s wall. I finally came up with the idea of constructing the towers to support the steel cut out designs, The variety of perforated and expanded steel, with bent steel rod creates an organic sense to the work. There is accommodation for the irrigation to be concealed within each structure, so the planter on top is watered, and the lighting at the base creates dramatic shadows, perfect for night time swimming.

Desert Towers

A note—I don’t use found objects or “recycled” materials in my work. Interestingly, most “new” steel is comprised of a high amount of recycled steel:

Steel is the most recycled material on the planet, more than all other materials combined. Steel retains an extremely high overall recycling rate, which in 2012, stood at 88 percent. The amazing metallurgical properties of steel allow it to be recycled continually with no degradation in performance, and from one product to another. Source: American Iron and Steel Institute (www.steel.org/sustainability/steel-recycling.aspx)

Contact details.

Joan Waters

website: www.JoanWaters.com

email: Joan@JoanWaters.com

Joan Waters, Arizona, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, August, 2016

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: