It is going back to 2015 but I love the simplicity of ‘Jacket Sparrow’ discuss.

Back in 2015, I had just finished an intense portrait of a meerkat and I was looking for something more loose and less dense in terms of thread. Also, I had reached a point in my new career, where I wasn’t so sure where I wanted to go with my art and not overly confident, that I will ever make it as an artist. Lots of doubts and little trust in my potential. So, I decided to go back to something I felt confident with and that was collage making – but it wouldn’t be me, if I didn’t add a challenge to it and so I went for a bird, a subject I had never stitched before in that manner. The reference photo I used for this piece spoke to me right away and sparrows are always popular with the crowd and so I went with it.

Jacket Sparrow

As the collage grew, my inspiration kicked back in and what set out to be a loose piece, turned into something fully embroidered. I just couldn’t stop adding details, which caused my fabric base to pucker and I was left with no other choice in the end, but to cut the sparrow from its base and to stitch it onto a new fabric background. I held my breath the entire time I was cutting along the edges of the embroidery, it was nerve racking having spent so much time on a piece and then having to chop it all up. When I then held the bird freshly cut in my hands, I knew that I needed to give him a less ordinary background and having been following the patch making trend on Instagram at the time, I decided to stitch him onto my denim jacket. I liked the idea so much of wearing my own art, taking it out into the public and creating unique exposure. It took me forever to find the right placement for it and I really loved the idea of its tail going underneath the loop at the bottom of the garment. There was no plan behind it all, one thing simply led to another and the learning curve was steep.

Jacket Sparrow, Detail

Tell us about your relationship with your machine?

I have three machines in my studio, which I frequently work with. One is a vintage, motorized Singer flat embroidery machine from the 50’s, a Bernina Record from the 70’s and my Brother machine I bought in 2011. All three have very different characters and produce very different textures.

I do not have names for them or take overly good care of them to be honest. They have no handmade covers or fancy stickers, but I am grateful for each one to call my own. I am fully aware of the torture I may cause them at times, the stop and go stitching, the endless hours they are ploughing through layers and layers of thread without any symptoms. So, if there is some kind of relationship, it is a respectful one. I am aware that I couldn’t work the way I do without them and I appreciate the fact, that they are all still going strong, all three of them.

When do you get cross with your machine?

Like every artist, I have bad days. Days where nothing works out, time seems to have been wasted because no obvious progress was made, or an idea didn’t work out as mapped out in the head. And it is on those days, that machines tend to tangle the threads, break their needles or refuse to wind bobbin thread – and it is on those days that I have zero patience with anything and that is when I get cross. Obviously totally wasting my energy by directing all my anger towards the machines, but it is the only vent at that very moment and frustration finds its way to be seen and heard. Luckily I have learned over time to simply walk away, after throwing that small tantrum, and switching the machines off for the day.

Discuss the full meaning of your masks.

What are they hiding?

What is behind their eyes?

The subject of the masks has developed over time. When I first started to look into the matter of endangered species and the rapidly growing loss of wildlife, I knew I wanted to use my art as a channel of information and to raise awareness. Back then I didn’t know exactly how powerful art could be, but intuitively I tried to give mine a deeper meaning.

So, the idea behind the masks is that I wanted to make the viewers connect with my subject.

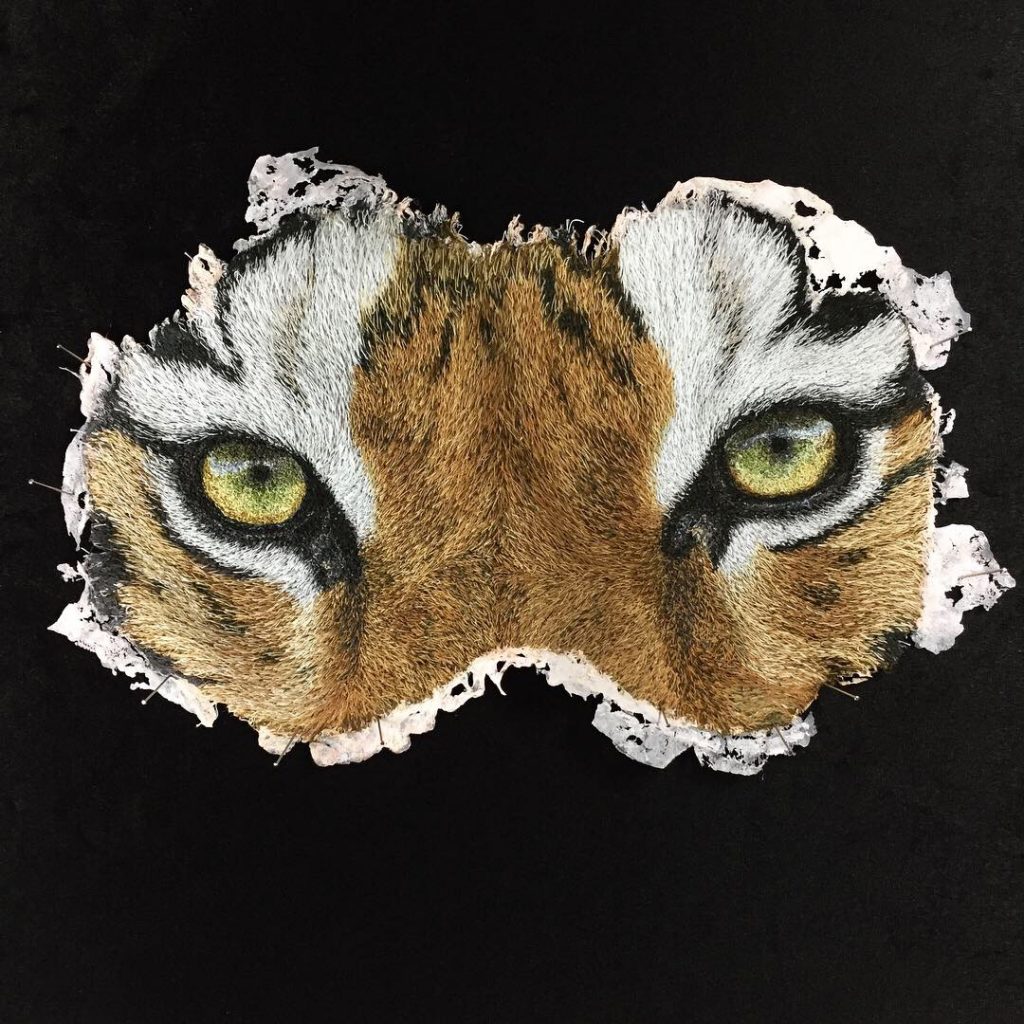

Mask – Sumatran Tiger

I wanted people to meet those animals on ‘eye level’ or equal terms and to make contact, because I believe that you can only care for something, if you are emotionally drawn to something.

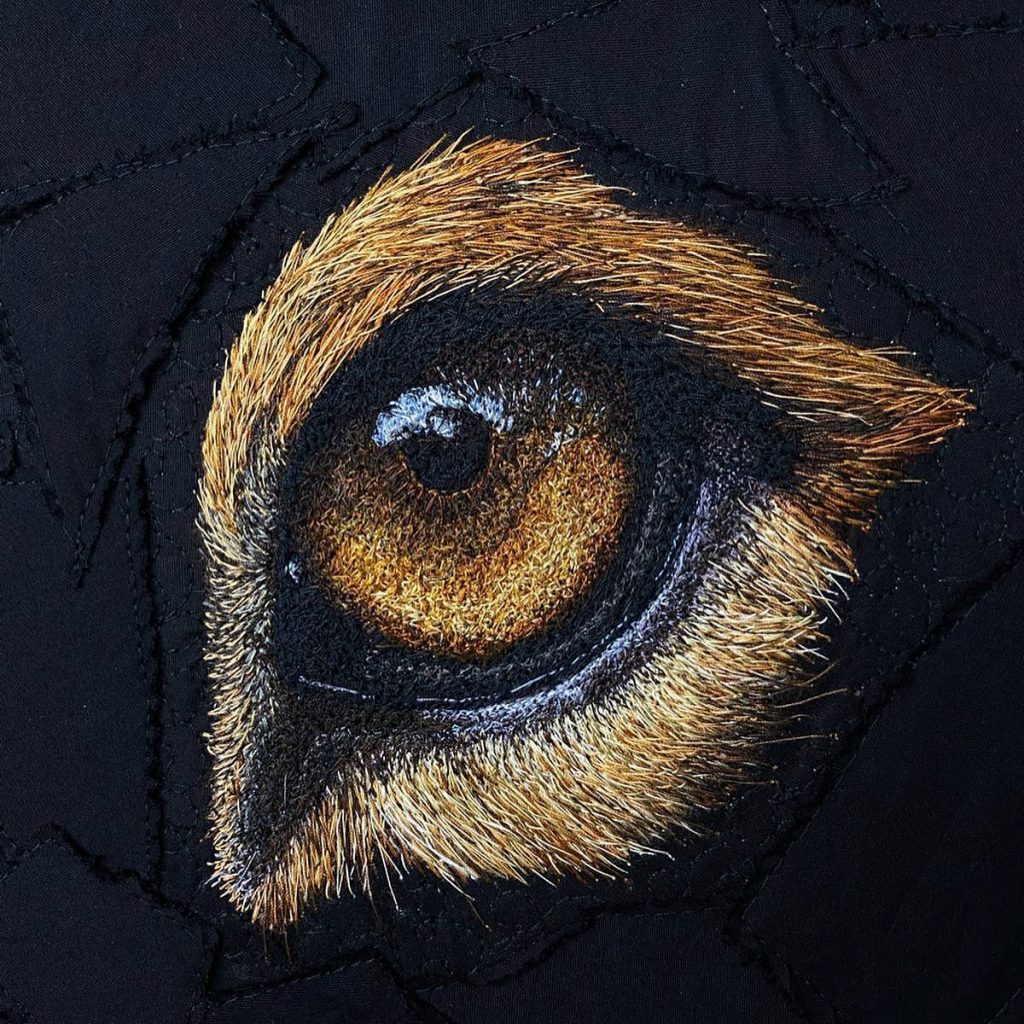

Mask – Snow Leopard

To me, those masks are bearing urgency, sadness and hope. They are hiding so many emotions, and every individual will discover something different behind their eyes. But I think the common ground is sadness regarding the plight of the species and their dependency on us humans to make a change.

With the current urgency that our planet is experiencing, having lost 65% of all our wildlife already according to Sir David Attenborough, my need to create more masks has grown over the past few months.

Show us two animals you have embroidered that are endangered.

Discuss the technical aspect of the work

The background to the animals endangered status

In 2016, I started to focus on endangered species and lending them my voice to raise theirs. I haven’t stopped doing so and I don’t think I ever will either.

Receiving feedback from my followers on social media always fuels my intentions to continue, as they let me know that they for example had never heard of a cassowary before, or that it is for example the plantation of palm trees for extracting palm oil, that destroys the habitat of orangutans. If I can make one person boycott products with palm oil in it, I have already made a change. If I can show people how beautiful a pangolin is, and explain how peaceful they are, they may teach their children and make them aware.

Orangutan. 90x70cm. Photography by Martin Wacht

If I can help make readers understand, that petting a baby lion in a roadside zoo is supporting a wildlife crime, they may think twice about where they will book their safari next. So embroidering endangered animals always comes with a message.

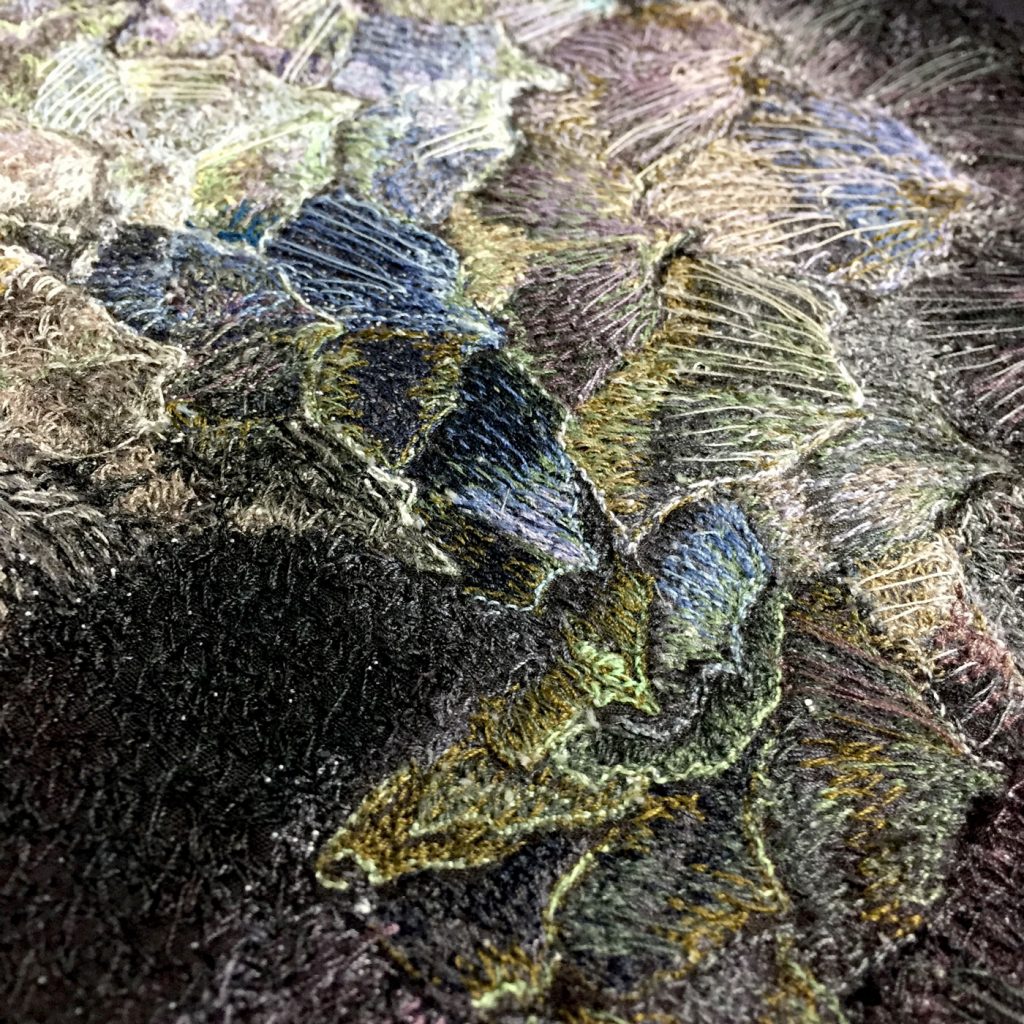

To discuss the process, I chose the portrait of the orangutan and the pangolin, as they entail three different techniques: fur, skin and scales. I mentioned before, that I like to make every portrait a bit of a challenge to me and those two definitely have been quite a journey and a stretch to my wings.

Both portraits, like all my work in large scale, start out with a simple sketch of the outlines of the subject on my base fabric. I often create a line drawing first and the transfer it on my calico fabric with a light board. The next stage is an extensive and very detailed fabric collage for which I usually grab my Batik fabrics, as they create a smoother look. Not that this would make any difference in the end product, as it will all be covered in layers of thread, but I have a need for the ‘ugly stages’ to be pretty as well.

Orangutan. Embroidery process

The most frequent question I get asked is: why do you create a fabric collage and not stitch directly on to your base? Now, there is a simple answer to that, because the collage becomes my navigational map during embroidery. I instantly know where a tiger stripe begins and where it ends for example and I can find the area I am working on much easier on my reference photo that I study a lot during the embroidery process. Sometimes I think I spend more time staring at the photo that embroidering the portrait, but it takes time to study all the details and to identify all the colours involved. The collage process also helps me study my subject in more detail and I familiarize myself with patterns, texture and fur growth direction for example. It lets me study highlights and shadows, which play a major role in photorealism.

African lion. 80x60cm. Photography by Martin Wacht

Once the collage is lightly glued down with regular glue stick, I start my embroidery process and that always begins with the eye(s). They are the windows to the soul, as they say. To me, they are the window to emotion and to connection with the viewer, and so I spend a particular long period of time on them. After that I work my way around the portrait, focusing a very small areas, no larger than 10x10cm at once, to really let myself zoom in and capture all details. When working on skin, like the face of the orangutan, or working on scales like the ones on the pangolin, I use freeform ‘zigzag’ stitching and build up the texture by applying light layers of thread in coordinated shades. Wrinkles and hard lines are added at the end, to make them more effective and they are always accompanied by a shadow and a highlight. And the big bonus of stitching skin and scales is, that you can always go back over them with another layer, if the tone needs adjustment – no unpicking!

The approach when stitching fur is very different to what I described above. Fur comes in neatly stitched layers, starting with the darkest colour, working up to the highlights and then going over the area with medium tones again for blending. The highlights are added at the very end and are usually single stitched hairs in the lightest colour available, to make them pop and create movement. I have learned that there is not one technique that can be applied to all animal portraits. As unique as they are in nature, as unique are the approaches in embroidering them. There are certain basics, but I have not once completed an embroidery that did not require me thinking about a new technique or completely out of the box. Not even stitching the same subject saves you from not having to think about new approaches and that is why I enjoy my work so much and love what I get to create, because it keeps me on my toes and keeps developing my skills and makes me journey so very unique!

You have lived and studied around the world. Comment on how ‘Global’ this has made you feel. (perhaps with a story)

After completing high school, I went globetrotting and lived seven years abroad to study operational management for film and TV in England, special effects make up in Canada, Tourism Management in Wales and working in hotels in Ireland and Spain. I tried to find my potential in all these years and one education formed the stepping stone for the next, totalling to six completed degrees with only one being of a creative nature. It simply wasn’t what I had myself down as, back then it never crossed my mind to become an artist. I enjoyed people and the company, I found pleasure in working in the service industry and being away from home. Connecting with people from all over the world literally made my world. But it never made me truly happy and was only a small fraction of my path to my true potential. After becoming a mum with 31, finally having agreed to settle down in one spot, my creativity started to flourish. Like it was waiting for me to hold my feet still and finally be heard. All the traveling and spending time abroad has been a vital factor for my artistic career, as I am able to share everything in English and making it easy for me to establish connections with fellow artists, event organisers and collectors. I feel that I can take part in the artistic world without many boundaries and much confidence, at least what language is concerned.

Tell us about the significance of finding your own personal working space.

Being a mum of two, I always had struggle to find time for my creativity. Carving that out for myself, created the need for my own studio and I am very blessed to have been able to ‘carve’ that out for myself too in our house. I now inhabit quite a large studio that I share with all my animals, and it has become my safe place. I have the liberty to create a mess without having to clean it up, I get to retreat and throw tantrums in it, I can let my creativity and emotions run wild and there is no judgement. It truly is my safe place and there is nothing in the world I would trade it against with.

Comment on the community of the textile world.

The textile art community is strong and incredibly supportive. Especially over social media, I have met the most kind and loving people, that are there for you on bad days, that celebrate with you every little sale you made and that tag you in ‘calls for art’ because they think you could rock it. It doesn’t really get better than that – artists supporting artists, women supporting women (and men, there are fabulous male textile artists out there too!). The hashtag #communityovercompetition says it all.

You often work on isolated parts of the animal’s body, eyes, or mouth. Why do you use these perspectives?

Very similar to the masks, I want to draw attention to the details of the endangered animals. I want my audience to take a closer look, to zoom in and discover not only single threads, but the utter beauty in our fauna! I want them to connect to the wild, to take the time again to appreciate the beauty in things. Time has become such an important factor in our society, that no one seems to take it anymore to stop and look at details. It is like people are trapped in a race and the appreciation of natural beauty is lost.

What background fabric and how many layers do you use?

My background fabric is mainly medium weight calico or a poly cotton mix, depending on the size of the subject. Calico is a lot more flexible and easier to stretch on artist canvas before framing, so this is my number one choice and a single layer is sufficient.

Explain the impact of using the humble embroidery hoop in your work.

When I started out with machine embroidery, there was a lot of experimenting with different materials. That also involved stabilizers of all sorts, trying to avoid the fabric to budge under all these layers of thread. It took a good two years to finally discover, that a simple wooden hoop in combination with the right fabric and the right density of thread would do the trick. No stabilizers, no cutting embroideries and transplanting them onto a new background needed.

Video

Video of working on you bird.

Questions that I want to ask after watching this video…

How many coloured threads do you use in this piece?

I don’t remember the exact number of coloured threads I used in this piece, but there must have been something like 45 of them. My rule of thumb is to use at least three shades of every colour that I identify in the reference photo, to create realism.

How do you set up the threads so that you have quick access to them?

I have large working tables next to my machines, and the threads are spread to the left of me, colour coordinated and in little groups. I need them to be all on display, so I have the chance to find the correct shade I am looking for. It does look very chaotic, but it actually has a system to it.

How do you achieve the translucency of the wings?

The wings have been an extra challenge, as I wanted them to be detachable and 3D. So, I practiced sandwiching a piece of golden organza fabric into Sulky Solvy stabilizer and stitched all the outlines and wing details onto the stabilizer in coordinating thread. I had to repeat that process three times before I got them delicate enough to match my macro image of a bumble bee. But the organza fabric worked a dream and really pulled off the realistic look I was hoping for.

Macro Bumblebee with 3D wings.30x30cm

Have you done any bugs or insects?

Apart from bees, I have never fully embroidered any insects or bugs. Although, coming to think of it, their textures and colours are incredibly beautiful, so maybe I am going to look into that subject matter soon!

What is your next project?

My next projects, that I am very excited about, are two pieces that once again highlight endangered species. For one, there will be another Amur leopard mask in the making and another chimpanzee portrait, of which I stumbled across its reference photo and instantly felt the need to translate it into thread. So, this is what I will be working on until the end of this year and I couldn’t think of a better way to celebrate the end of it – with an important statement to protect our wildlife!

Take one piece that has both given you joy to make and have a great background story.

If I had to choose a piece that has given me the most joy to create, I would pick my portrait of the Gombe chimpanzee. I received the commission from the Jane Goodall Institute – Austria to create a gift for the world-famous anthropologist and UN ambassador of peace, Dr. Jane Goodall, to celebrate the beginning of her extraordinary journey 60 years ago in the forests of Gombe, Tanzania.

Dr. Jane Goodall commission. 40x40cm

I remember spending a long time trying to find the perfect reference photo, the perfect pose of a chimp from Gombe National Park , and my joy when I suddenly found it. I am not sure if it was the pose of the chimp, the lighting I chose, or the emotion the animal carried, but it turned my embroidery process into bliss. I chose my vintage Singer machine for it and in unity the portrait evolved with such ease. There were tough areas to come by, but none that caused anger or frustration. Stitching the single hairs on the wrist and the top of the head just came naturally and this has also been my very first portrait that had no stitching of eyes. The first piece, that wasn’t defined by the look or emotion in the eye, but the pose and shading.

The portrait is still with me and waiting to be received by Dr. Goodall in person, once traveling and events are safe to host again

Discuss your comment, “If you haven’t found your favourite animal here (on the site). No worries I always make time for special commissions.

African Tree Pangolin. 50x50cm. Photography by Martin Wacht

I have an incredible community and a very supportive environment around my artwork and over the years built up a small field of collectors who appreciate my work and fund my business. For a long time, I just created work and every now and then one would get adopted and find a new forever home. But over the past few months, I have had people approach me for awesome commissions and that was a great experience for me, because I got to do animals, like a Great Horned Owl, that I would never had thought of creating. An incredible challenge and a first for me to dive into stitching feathers.

African Tree Pangolin, Detail.

I welcome challenges at all times, as they mean growth to me and those special commissions stretch my wings a lot

Contact:

Janine Heschl

IG: @textile_wildlife_art

FB: www.facebook.com/textilewildlifeart

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, November, 2020

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: