Heather Shimmen Printmaker - Melbourne, Australia

Can you please discuss the influence going at 14 with your family to Papua New Guinea has had on your art?

Travelling to and staying on my parents farm in Papua New Guinea through my teenage years was quite a revelation, not only for the work I was to make in the future but profoundly, on a personal level. Those experiences did not translate or become evident for some years. I think it was an experience that percolated within me for a long time. Even though it is many years ago now, since I was last there, it is still a vivid living memory.

After contemplation, I realize my interest in body marking, including scarification tattooing and piercing, had its origins from this time when I first encountered tribal people who had all, or some, of these forms displayed on their bodies. It was very confronting for a sheltered white middle class girl from a Melbourne suburb in the 1970’s.

Today, you might see in evidence on the streets of Australia and other Western countries, body sculpture and decoration. Instead of bones pierced through noses you will see stainless steel pins and spikes on most parts of the body and face while the tattooing can be incredibly eclectic and not restricted to tribal marks.

Both tribal and western approaches might be fundamentally about a connection with tribe, or even purely for decorative reasons. It is certainly a human practice seen across many societies from the earliest human groups throughout human history.

References to some of these practices of piercings became more in evidence with two small linocuts I made about 13 years ago. One is called ‘Beauty Spot’ the other ‘Pierced’. In both I attempted to bring together a number of disparate elements in cohesion. There are references to witches and piercings, both in tribal cultures and those seen in our society – from the punks of the 1970’s to the mainstream youth culture of today. My piercings are not conventional and include broomsticks and fish hooks, although there are some safety pins – invented by the Etruscans and found in the ears of individuals from Papua New Guinea, the UK, Australia, the USA and elsewhere. I like the play with time, history and culture.

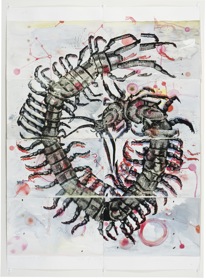

In the last couple of years I have introduced a stronger entomological element into my work. Much of this stems from my experiences up close and personal with some very large and many legged creatures found in Papua New Guinea. One that has always stayed with me, and is derived from that time was my encounter with a hillside moving with arthropods – centipede like creatures, all about a foot long. I had gone down to retrieve a ball at a friend’s farm, which was partial rainforest. Needless to say I didn’t linger there for very long!

Your training was at RMIT University, how has this influenced you?

When I studied at RMIT it was quite a small Fine Art Department but it was populated by large personalities in the teaching staff and my fellow students and contemporaries. It was quite a rarified place then as many of the lecturers were well known artists of the day who for the most part opened up ways of making and considering art and challenged our preconceptions about this and other aspects of life. Most of the lecturers were masters in their fields and although a painting major I became enthralled with printmaking from my first class. With people like George Baldessin, Greg Moncrief, Tate Adams, Graeme King, Jan Senbergs and many others who imparted not only technical expertise but some of them became mentors in many ways and have supported mine and numerous other ex student’s careers.

The institution felt like a family in a kind of a way especially by third year. We socialized with our lecturers and subsequently I am still friends with many of them. Over that period when I was a student many committed artists came out of this University many who are still making art and some exhibiting all these years later.

Both those lecturers and contemporaries have been very supportive all along the way. I have exhibited, shared studios, houses, worked, travelled and had life experiences with many of these people I encountered first at RMIT as a student.

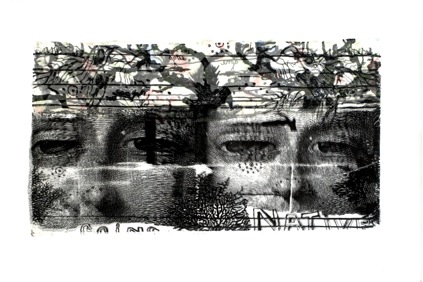

’Going Native’ Linocut on paper and organza

You have also taught at RMIT, as an artist did this role help your art?

It is a very different place now in terms of the departments and faculties however there are still a couple of familiar faces around the place. It has grown to be a much bigger institution. I teach and have taught in many other places besides RMIT from TAFE, private providers, Monash University and the Catholic University. I find that attempting to impart enthusiasm, a sense of exploration, a curiosity and professionalism that was passed onto me by my lecturers from the past is rewarding and often challenging.

The students also give back a great deal and it is the interaction with many and varied people, their stand points and the way in which they view the world is something to learn from. It’s a two way encounter.

Of course, being part of an institution which has a body of staff and fellow exhibiting artists, often results in invitations to exhibit. When time allows there is also the opportunity for discussions with people who specialize in my field of printmaking .It is in the office or studio, where recent technologies and new work by contemporaries is viewed, that problems might be thrashed out. It is also a very supportive environment.

Can you expand on three pieces of your work and in doing this show the development of your art and also explain the technique you have used?

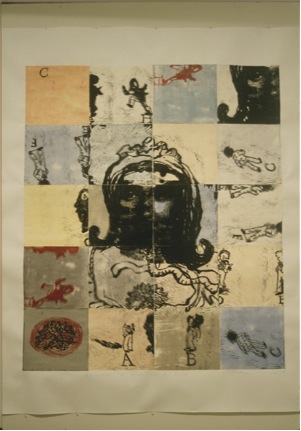

1. ‘Lost 1, 11 and 111’ – Linocut on felt

I have made a number of works around ‘The Lady of the Swamp’ and ‘Lost 1, 11 and 111’ are a small suite of works of same dimension, treatment and concept as part of a series. They draw on the story of Margaret Clements who disappeared in mysterious circumstances in the 1950’s from her almost submerged mansion, ‘Tullaree’ in South Gippsland. It is an alluring and fascinating tale.

The story is one of a ‘riches to rags’ tale. The female protagonist lives an indulged and hedonistic lifestyle (including travel in the grand style).This life deteriorates into poverty and destitution.

Margaret was last known inhabiting the crumbling edifice surrounded by the lapping of the encroaching swamp. No remains of her have ever been found!

A mythology and preoccupation of the ‘female’ within the Australian landscape is a central theme in the work. There are many stories long since forgotten. The colonial woman suffered much hardship, often weighed down by the trappings of the fashion of the time, most likely existing, forgotten in an isolated environment.

2. ‘Cry’ – linocut on paper and organza

There is something intangible that I respond to in birds. There are many things that drive me to make images of them. It is a duality, in part their fragility versus the endurance they seem to posses.

Within human mythology and folklore this dual aspect is evident in many cultural stories; evil versus good, death versus life, foolishness versus wisdom and so on.

Dreaming of birds is said to be a portent of important happenings in one’s life. There are many potent stories.

Birds have an unmistakable outline – one that is beautiful and completely contained and yet when placed in a forested setting this embodiment metamorphoses and becomes embedded in its surroundings. An image created entitled ‘Cry’ typifies this. The bird’s solidity falls away into a curtain of twigs that indicates a body, or does it. I like to evoke ambiguity!

It is some of this quality and an attempt to capture something of the essence intrinsic to birds within this image. The bird in this case is a curlew, a water bird with a distinctive beak and eye (I have studied them myself by hiding in the mangroves so as not to scare them.)

This image has inhabited my imagination for some time and is translated onto paper as a linocut incorporating organza.

3. ‘Swarm’ – linocut and ink on paper 2011

This work is made up of multiple panels and is both linocut and calligraphic washes of ink and very loose stencil shapes of flying insects. It brings together elements of a narrative, both personal and historical and even a micro social statement as well.

In this work like many I have made, the female takes a central role. I strive to make these females of the species appear as imbued with strength and power and a touch of introspection. I like them to appear ambivalent, as I think this female does, it is an unbalanced and even unsettling image.

I am sure my way of portraying the female image comes from many places – from the strong matriarchal element, present in my family background, from my love of both Goya’s and Velasquez’s portrayal of women, to my interest in the many infamous and famous historical women who appear in both literature and portraiture, often based on real life saints, courtesans, witches and heroines. I think I am a little in awe of these kinds of women.

In part, this image is in collision, in terms of narrative and its fractured treatment. It is not one story but a few, one of which derives from the story narrated earlier on in this conversation. Its origins come from South Gippsland where I mostly now live and from a real tale of mystery. In one episode the female protagonist Margaret Clements and her sister lived in a once luxurious but now crumbling mansion in a swamp. One night there was major flooding with hurricane like weather systems and they were stranded and overrun by all manner of creatures both large and small. As they huddled on their beds an army of these insects, snakes etc flowed like an avalanche and joined the women on their refuge from the water lapping in the rooms of the house. It was this story that evoked a strong response and was an influence on the image.

In combination with this true tale are others that have been amalgamated within the image, including my own personal response to the experiences of the two sisters. There are other stories of beguiling women entertainers like Lola Montez and her infamous 19th Century Spider Dance that has echoes in the creation of ‘Swarm’.

I have been developing a female character that encompasses and encapsulates much of these kind of women over the last 8 years, she is called ‘Matilda’ and has been represented waltzing at times and perhaps there is some of her in this work.

She has been devised in response to the famous representations of male heroic figures including Burke and Wills and Ned Kelly by artists, at least well known in Australia, such as Sydney Nolan and Arthur Boyd.

Winning the Silk Cut Award in 1998, how important has this been to your career?

Winning the Silk Cut Award has had a profound effect on my career and also myself, personally. To begin with it was quite a shock to win and one that had positive implications. It seemed like a big metaphorical tick for the work I was making (at least by the judges at the time) and set me off in quite a new direction for my practice in terms of process, imagery and concept.

Until that time around 1998 I had predominantly made paintings and drawings, although in the late 1970’s and 80’s I had produced many etchings and had made a number of linocuts but had never exhibited these. I was at a turning point where I had recently left my job teaching printmaking at NMIT and decided to enter the Silk Cut Award. I had the time and mental space to do so. It also fitted in with my family circumstance. I had a young child, 2 cats and a partner and nowhere to keep chemicals in my studio or house safely. Lino printing is great in terms of these issues and is relatively safe compared to some other printmaking processes.

There was some kind of synchronicity happening at that moment in time as the imagery I was exploring and the process of linocutting came together and since then I have almost exclusively been making linocuts. It was a moment in which the process was the vehicle allowing the visual ideas to manifest in a concrete way. The fact that I make my work as Lino prints is not so crucial to me. The images might be made as drawings or paintings but it has become important in as much as it is a way to express my ideas better than they might if created by other technologies.

You have travelled extensively in Australia, in particular in Northern Australia, how has this inspired your work?

I am a natural collector of flotsam and jetsam as I am with ideas that inform my work. Part of this collection comes from travel and like any life experience they are ones that slowly emerge.

A number of years ago myself and my partner were in the northern parts of Australia, around the Darwin area and environs and went out to a place in Arnhem Land called Arrmoduc. It entailed a flight in a small plane, then a very bumpy truck ride followed by wading through swamp accompanied by a man with a gun to shoot at animal attackers e.g. pigs and/or crocs. Finally we scrambled up out of the swamp onto extensive rock escarpments. It was an amazing place, not only was every rock face covered in layers of ancient ochre paintings of spirit figures , hand prints , dreamtime figures and images of Macassan ships but there were many burial sites in sheltered rock alcoves. One of the most outstanding experiences entailed visiting a cave completely full of human skeletons which evoked memories of my visit to the Capochin caves in Rome – also crowded with human skeletons stacked and often arranged in decorative formations.

It was the overlaid imagery on the rock escarpments that I felt a connection to. Serendipity and the accident of the overlay, as each layer transforms the whole over millennia. I have seen this in the form of graffiti on other more contemporary walls in Melbourne from the 1980’s (I participated in this), and particularly now in central Melbourne. Also, other cities like London and Paris and most particularly on the wall that divided east and west Berlin.

I spent a lot of time documenting all these walls in still and super 8 film images. Inadvertently this has manifested itself in my work and whilst initially I layered my paintings with both multiples of paint and meaning, I now endeavor to translate this as a Linoprint.

You often work with other artist in exhibitions can you explain how you find this?

Luckily, so far I have always had very good experiences with the people I have exhibited with and have learnt much from the processes that happen when negotiating exhibition spaces and the actual hanging and installation process.

I have made collaborative work in the past with a group of three other female artists and we titled ourselves ‘Refluxus’. Not only did we make quite a large body of work together but we exhibited our wok in both the Bendigo Art Gallery and in Melbourne. It was loosely based on the notion of the Surrealists Games called ‘The Exquisite Corpse’ in which each participant devised a set of rules resulting in a work in some form in which we had all been part of making. My favourite amongst many was the Monica Lewinsky dress (of Bill Clinton fame) and the 125 rolling pins that sang and were constructed in many and varied ways.

Most recently I have done a residency with Mandy Gunn at the Art Vault in Mildura where we collaborated using printmaking techniques and referencing local culture, flora and fauna. It was a wonderful experience in which a lot of work was produced. It will no doubt influence my other work in the future in ways in which are hard to quantify.

During the process of the collaboration, experimentation and play with media and image was free form – in which the accident brought up some interesting and unexpected results.

Can you explain how you fuse entomological images with historical work?

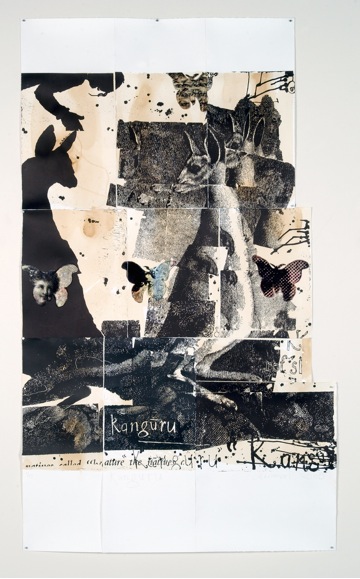

I made a work titled ‘Kanguru’ in which there is an amalgam of the historical and the insect – in this case butterflies. The work is a fractured and reconstructed image based on the iconic creature that is the Kangaroo. The idea derives from an original drawing made on Captain James Cooks’ first voyage to the Antipodes by Sydney Parkinson. When back in England, Joseph Banks (also on this voyage) passed the drawing on, plus a skin of the animal to George Stubbs the renowned painter of horses. He subsequently made a painting in a somewhat heroic style and further to this the engravers of the day reinterpreted this image for the many broadsheets of the day. Mine is another reinterpretation into a contemporary context.

The ‘butterflies’, which appear centrally in the work, are an important element. They represent something that occurs in both the natural and human worlds, a migration of sorts. In part they reflect the atmospheric phenomenon, in which upper wind currents carry material over great distances – anything from spores and seeds of plants to, sometimes, even creatures like butterflies and frogs – in the process facilitating an unintentional colonization from one land mass to another. My ‘butterflies’ arrive carrying those plant particles, small animals and also humans in an inevitable, inexorable migration. In this case they reference the Australasian region where, over time, movements of plants, animals and people have altered the landscape and environment with sometimes devastating effect.

There are shadows that flit within this work, indicating the possible unseen consequences of human and other alien interactions that might infect or affect this unique Australian animal.

‘Kangura’ – Linocut, ink and tea on paper and organza

You work beyond the boundaries of a printmaker, can you explain how you work beyond paper?

I think like a painter and am always considering other and alternative ways to develop my practice. I do like to get the print off the page and so have been open to other surfaces and other ways to explore this media.

I work on fabrics that are both opaque and transparent. The transparency allows an increased dimension to the work and a play with image.

The other fabric I have incorporated into my work is the felt used in blankets for etching presses – after it has been used for this purpose. It’s not something I can buy from a shop! The idea to print on it happened while working at a TAFE College where students were using some blanket off cuts for rags. I could see the potential and luckily was correct when, after experimenting, discovered it printed beautifully from the block.

‘Hoot’ – Linocut on Felt, 2011

You have a done a series of pop up books, tell us about this aspect of your work?

The pop-up books had their genesis many years ago when I worked in TAFE and landed the unenviable job of teaching a group of disparate individuals including a group of teenage boys, a design subject. One of the last projects I set turned out to be the most memorable and successful and it was based around the concept of the pop-up book. I made it very open and experimental with the only proviso that they be oversized. The students took to this topic with gusto and produced wonderful work, one I remember being entirely created with sticky tape!

The idea and desire to make some myself has been with me since this time and when I was invited by Dr Ruth Johnston of RMIT Printmaking to participate in a Summer Residency at the University this seemed the perfect opportunity to further my experiments in making something loosely based on this paper technology.

I had made one prototype previously, which had been exhibited at Gallery 101, Melbourne, called ‘Anthology’. Using this as a starting point and with much marquette making and experimentation I began and eventually made a group of works exhibited at Project Space, RMIT, Australian Galleries and NETS Victoria travelling show, under the title ‘Suspended Anima’.

My intention was to not make a conventional book but one that could be suspended, had elements of pop up three dimensionality and that was shaped in a form that I hope suggested an animal/insect form. I considered a number of possible ways in which to construct the ‘books’ and ultimately decided on using a very heavy weight, high quality paper. I was able to play with media, process and construction techniques.

‘Suspended Anima’

Linocut and pop up elements on paper

I have made them, each following a methodology in the way I cut the outlines but within this perimeter, experimented with variation. I wanted them to be slightly scary as insects are when looked at closely and considered as if they are many times their actual size. I have always been fascinated by the creatures that lurk under pieces of wood or in crevices within the spaces we cohabit, that inexplicably scare us, considering we are giants in comparison.

Your recent work at the Art Vault has a Historical French, feel am I seeing this correctly?

A French feel is not one that is intentional but rather incidental. I do reference women’s costumes and fashion from a time when, in Europe, the epitome of design was centered and radiated from Paris. I do collect images of women from a wide demographic – including a range from aristocratic through to the peasantry of the period around the French Revolution. I am fascinated in the way the ladies of the elite class adopted the costume of the poor women of the time (as did Marie Antoinette herself) whilst living a hedonistic existence. They seemed to yearn for a simpler existence without comprehending what this existence really entailed. Some of this may be infused within the work but I am not intending it to be an overriding theme.

Tell us about your studio space?

I am very lucky and currently have two very different spaces. One is in my house in Balaclava, Melbourne, which is a classic old terrace house circa 1880. I am not the neatest of people but keep it to an ordered disorder – otherwise I become distracted if chaos overrides the space completely. It is a large room made larger by demolition of a lath and plaster wall (destroyed the vacuum cleaner) and the studio faces north. I have an etching press which is medium sized which has been used to print my smaller works over the years. Much of the Lino cutting is done in my kitchen, cooler in summer and with all amenities close at hand.

My other new temporary space is a shack, in the bush on our block in South Gippsland. We are currently relocating there and will be building a big printmaking studio. I have recently purchased a large etching press on which I can print my larger blocks. Until recently, Monash University has kindly allowed me to print on their large electric press, which has allowed me to make my works with larger unbroken areas of Lino. Sometimes I have cut the blocks down into smaller sizes and then assembled as larger works. This presents different problems and other kinds of outcomes in imagery and possibly, in the reading work.

Your work is owned in major Public Galleries. How does it feel to get the call telling you they have purchased your work?

It’s very exciting when a major collection, either private or public purchases my work. Of course it is a sale, which is great, but also an endorsement for myself and the work I make. It is especially pleasing when regional, state and national collections purchase.

What are you working on currently?

I am currently working towards an exhibition in October at Australian Galleries and two group exhibitions – one at La Trobe Gallery, Bendigo, in May and another at Maroondah Gallery in October. At present I am making Linocuts that will be printed on paper and am considering some other unorthodox techniques which have not yet been entirely formulated. The themes continue on from older work but transform, I hope, into new outcomes.

Contact details

enquiries@australiangalleries.com.au

Heather Shimmen, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2013

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: