Gráinne Cuffe Printmaker - Dublin, Ireland.

Can you discuss the techniques you are currently working with?

I am currently working with traditional etching techniques: aquatint and line. I use Ferric acid, and work on copper plates.

Over the years you have taken inspiration and academic direction form far and wide. Discuss the importance this diversity has had on your art?

Especially as a younger person, I felt a huge need to leave the comfort zone of familiar surroundings, be that studio or home town. An appetite for academic direction led me to the Tamarind Institute, in New Mexico, where I successfully completed a Master Printer course in Lithography. In hindsight, even more formative an influence than the Tamarind experience was the Fulbright Scholarship with was a brief visit to Gemini Editions in Los Angeles, where I saw gorgeous huge etchings of David Hockney’s beautiful simple silhouettes, profiles of heads. These etchings were approximately 4 Feet x 4 Feet. Plus an exhibition of James McNeill Whistler’s etchings, in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which I saw on the return leg of the Tamarind trip to the States, was also a huge influence.

Every studio I have ever worked in has its own ethics and set of reverences. In Giorgio Upiglio’s Grafico Uno in Milan, an Italian government Scholarship, I was intensely impressed by the woodcuts of Mimo Palladino, their graphic sophistication and simplicity, and mostly the intensity of saturated colour, and their large scale. While Central St. Martins in the late eighties opened my eyes to tonal value with aquatint.

Coming in more closely, can you comment on the influence Norman Ackroyd had on you art?

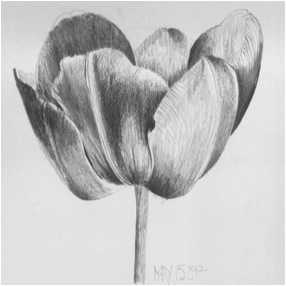

Norman’s theory was that you could get all the colour you wanted using black ink, and white paper. He was strict about this. He taught me for 2 years at Central St. Martins, London. I added a touch of blue, or green to the black, to survive the restrictions. He wanted us students to push those tonal values as far as possible, and using tone to make light/colour. This generated a love of the mesmeric qualities of aquatint.

Norman’s theory was that you could get all the colour you wanted using black ink, and white paper. He was strict about this. He taught me for 2 years at Central St. Martins, London. I added a touch of blue, or green to the black, to survive the restrictions. He wanted us students to push those tonal values as far as possible, and using tone to make light/colour. This generated a love of the mesmeric qualities of aquatint.

The Chester Beatty Museum is a worldwide must-visit while in Dublin and a generous supporter of the art world. Discuss the exhibition and your involvement with the Chester Beatty Museum?

The Chester Beatty Museum is a worldwide must-visit while in Dublin and a generous supporter of the art world. Discuss the exhibition and your involvement with the Chester Beatty Museum?

How did you become involved?

From my first visit as a 12 year old to the Chester Beatty Museum, I had felt a strong connection to the graphic work I had seen there, especially an iconic Japanese screen of staggered irises, a show of Albrecht Durer’s etchings, Mughal paintings, and many precious and beautiful watercolours and prints from Japan. Frequent visits to the Museum never fail to amaze, always feeding the visual appetite for more…this collection has fired the imaginations of many members of the Graphic Studio, and the delights of gardens seemed to be an interest common to both the collection, and to our members.

We felt that collaboration between the two institutions could benefit both, and make for a successful show. Hugely generous with their time, curators of varying sections of the collections introduced the artists to pieces we had not seen before.

What it was like to become a co-organizer of Gardens of Earthly Delight?

It takes a lot of meetings to organise a show like this. It is great to work out all the many details together, and exciting when the show is up and selling. It feels like one is giving back to the Studio. It was a hugely successful show, and a wonderful collaboration between 2 iconic Dublin institutions.

Can you tell us a little about the Chester Beatty (for those who don’t know about its collection)

Sir Alfred Chester Beatty 1875 -1968 collected treasures of beauty and wonder dating from 2,700 BC to the present day. Egyptian papyrus texts, Japanese woodblock prints, European medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, Books of the Ancient world…now in this vibrantly run, small Museum. Housed in a purpose built building within the confines of Dublin Castle in the City Centre, The Chester Beatty is always an inviting treasure chest to visit.

What’s it like having your work in their collection?

It is a huge honour and I am extremely proud and pleased to have 2 pieces of my work in the Chester Beatty Collection.

You joined the Graphic Studio in 1979. Explain the importance of both the studio, and collaboration with other printmakers has and still has on your art?

The Graphic Studio offers me all these positives:

– Sharing technical information about the work.

– Being in an atmosphere of work.

– Exposure to approaches radically different to one’s own to the making of an etched image.

– A wide variety of visual language in terms of the final image.

– The talk about the making of an image.

– The enthusiasm about visual language.

– The shared love of paper, colour, the end effect.

– The shared fascination of the progress of an etched image from start to finish.

– Constantly meeting Painters and Sculptors who come there to work collaboratively with Master Printers on the Visiting Artists program.

The Graphic Studio Gallery which the Studio owns, show my work.

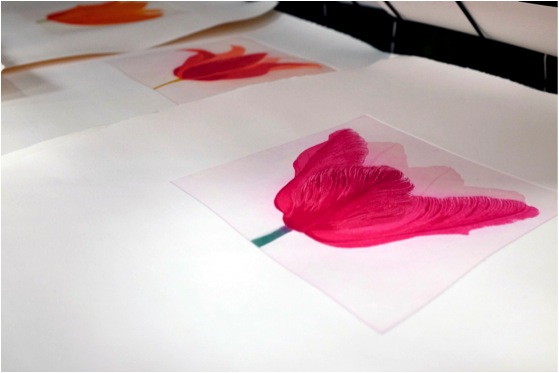

Collaboration with other printmakers in my case currently means I need to work with another well trained printmaker on the larger pieces because it would be physically impossible to achieve the printing a successful print on my own. The weight of the large plates is considerable. They need 2 people to handle them. It would be counter- productive to work on these on my own. It is at the colour proofing and editing stage that I need to ask a skilled printmaker to work with me. Inking up the plate may take hours, and you have to be time-aware, because some ink colours dry and will not print properly.

Your work is described as BIG can you explain the constrictions that size place on your art within the printmaking field?

The main constriction is the size of the press bed in Graphic Studio. My metre square plates fit easily, with ample room around the plate. As I use my studio in Wicklow for working on the plates, I have recently invested in a wonderful new acid bath from Polymetaal, Holland, which easily fits the larger plates. I love BIG. The generosity and expansiveness is good.

Expand on your work ‘Delphinium 11?

Thinking I was totally finished with Delphiniums, recently having completed Delphiniums I, Delphinium II was inspired by a large stand of wondrously stunning delphiniums on a sunny June day in a neighbour’s garden. The leaves articulation is different to Delphinium I, more 3dimensional, and with a variety of bright greens. The blues and purple-blues are also different. In that garden, I felt a bit more could be said to honour the Delphinium statement. I felt I hadn’t said it all, yet.

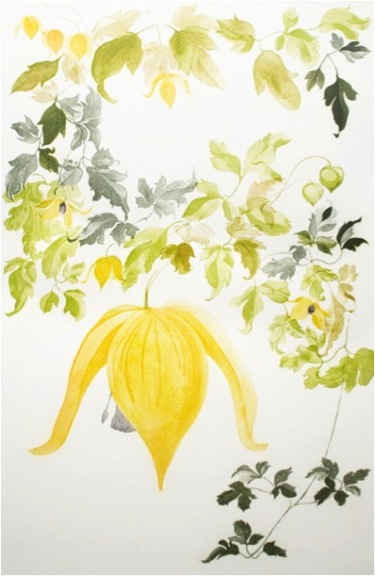

You call ‘Clematis orientalist’ “the big one”. Can you explain this?

Clematis Orientalis III is a large rectangular 4’6”high x 3’wide etching. I have made 2 smaller etchings of the same plant, for A Natural Selection – a show which was originally a fund raiser for the Studio, 100 artists contributing a limited edition print, image inspired by National Botanical Gardens, Dublin.

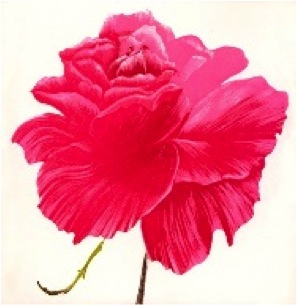

You work with both plants and flowers how would you categorize your work?

In describing my work, the most accurate words are: Loosely Botanical.

That might be a category?

By adding that Georgia O’Keefe, the American painter, has been an influence will give a sense of clarity.

I have never been able to describe my work with accuracy, using words.

Your work has such a very strong Botanical aspect, discuss?

Adding in explanatory elements of visual interest is a nod towards Botanical illustration of the past, where much information is on the page. My extra elements are there because they balance a composition, and are very carefully balanced in themselves. They are not intended to be botanically accurate. Some plant elements are extremely sensuous visually and although tiny, are magnificently beautiful: wonders of design, and the Bauhaus principle ‘Form follows function’.

Adding in explanatory elements of visual interest is a nod towards Botanical illustration of the past, where much information is on the page. My extra elements are there because they balance a composition, and are very carefully balanced in themselves. They are not intended to be botanically accurate. Some plant elements are extremely sensuous visually and although tiny, are magnificently beautiful: wonders of design, and the Bauhaus principle ‘Form follows function’.

When working on both exhibition layout and print size how do you decide on the size of the work?

Exhibition layout is usually a balance between large and small works, depending on the constraints of the gallery. In deciding about the size of an etching, if I feel an image of a plant will make an adequate visual impact, then the large format will work. At the drawing stage this is assessed. Drawings may start on a small scale, then develop into a larger format. The plant also has to have enough visual drama to hold its own on a large scale. Often, holding a magnifying glass to a plant is the only way to see the detail.

Exhibition layout is usually a balance between large and small works, depending on the constraints of the gallery. In deciding about the size of an etching, if I feel an image of a plant will make an adequate visual impact, then the large format will work. At the drawing stage this is assessed. Drawings may start on a small scale, then develop into a larger format. The plant also has to have enough visual drama to hold its own on a large scale. Often, holding a magnifying glass to a plant is the only way to see the detail.

If you want this detail to be a part of the image, scaling up is the only solution. Degrees of admiration and wonder and recognition of a magnificence [to do with the visual impact] play a part.

Where do you find your subjects (plants and flowers)? Are you, like many, a keen gardener?

Where do you find your subjects (plants and flowers)? Are you, like many, a keen gardener?

As a great admirer of the world of plants and flowers, yes, my subjects are mostly from my garden. If I was to let myself get swallowed up by my very wild garden and the notions it inspires, I would never get an etching either started or finished.

Many of your works can be found in hospitals and also at the Dublin Family Law Courts. Do you see your work as calming? How would you describe it?

Many of your works can be found in hospitals and also at the Dublin Family Law Courts. Do you see your work as calming? How would you describe it?

Some of my work is calming. I relish calm. In calm, I get space to think thoughts, have new ideas, and make progress with the etchings.

Calm lets people breathe about the goodness of themselves, potential for happiness and positivity of life.

When the ingredients of balance, calm, sensuousness are at an optimum in a piece that is when I feel it is acceptable. A visual harmony has been worked towards and concluded.

Although being collected by Museums etc. is wonderful, having my work in places where people are stressed is important to me. I have had excellent feedback about my work in the above; a settling down of upset and raw nerves.

Contact details

grainnecuffe@gmail.com

http://www.grainnecuffe.ie

Gráinne Cuffe, Dublin, Ireland

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October, 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: