Gjertrud Hals Textile Sculptor

Explain about your recent work with copper wire.

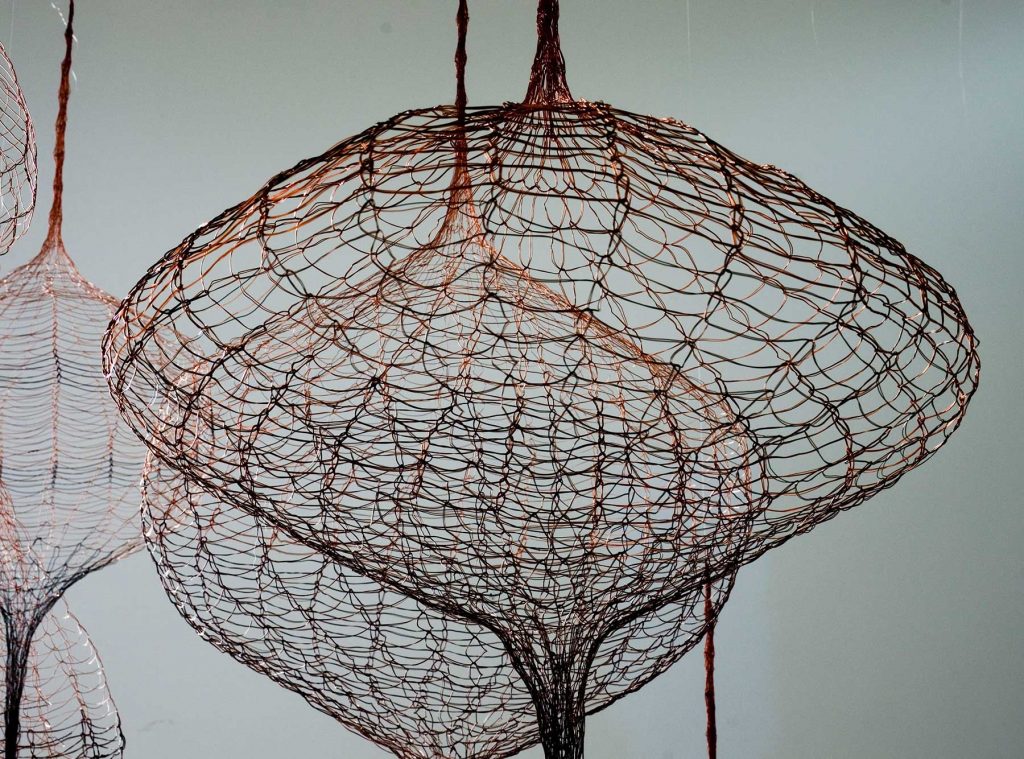

EIR series, Knitted copper wire, Photo by Sjur Fedje

For the last 2-3 years I have been working with copper wire, making 2D as well as 3D works. My father and grandfather were metalworkers, making and installing engines for the fishing boats. Our family was living close to the factory, and I found it thoroughly fascinating to see the different metal materials that they used.

For years I had been thinking about how to use metal in my artwork. Occasionally I had been using metal wire and various metal objects, but not as a central medium.

EIR series,Knitted copper wire, Photo by Sjur Fedje

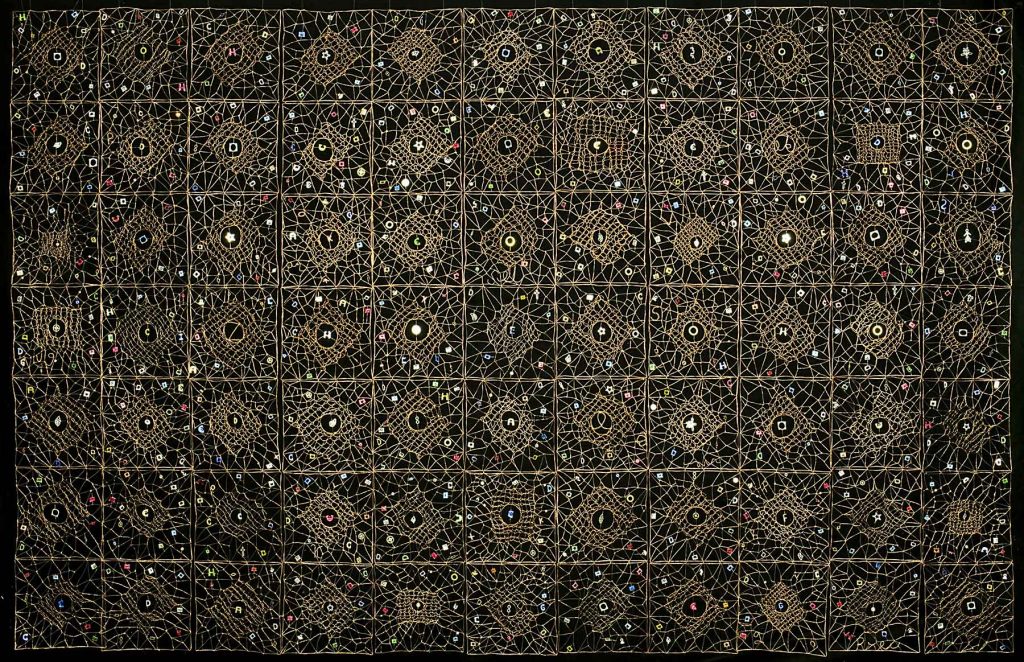

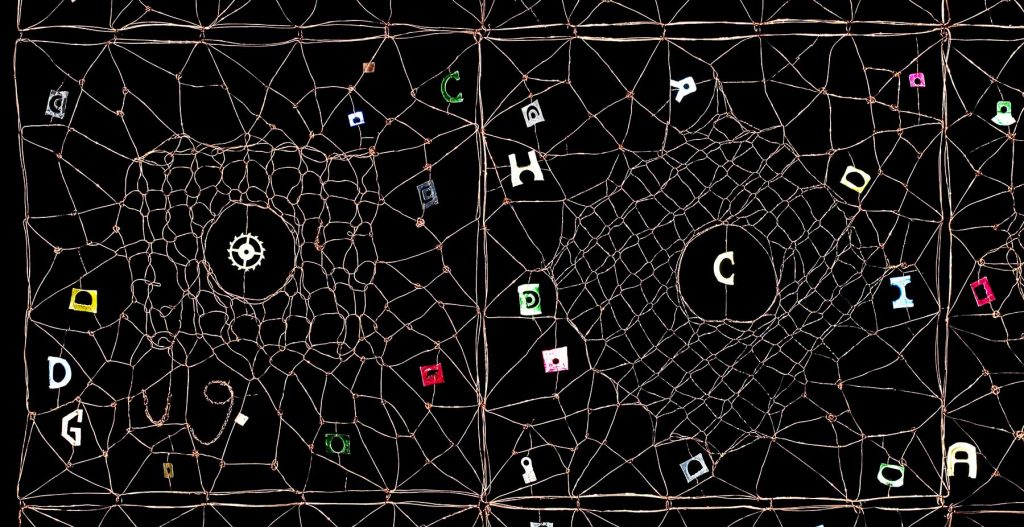

After my parents died, in 2013 and 2017, I wanted to make a memorial piece. As knitting was my mother’s favorite hobby, REQUIEM was made of knitted copper wire from my father’s workshop, combined with small items from their estate and ring-pull tabs from beverage cans.

Requiem, Knitted copper wire, 2019,Photo by Sjur Fedje

Eventually I also wanted to make 3D artworks with metal wire, and I am now working on the EIR series, knit on big circle- shaped frames. Dark colored wire from dynamos and motors is used together with shiny, reddish wire from electric cables.

Requiem, detail, Knitted copper wire, 2019,Photo by Sjur Fedje

The title EIR, meaning corrugation, is pointing to one of the characteristics of copper, that I want to emphasize in this project.

Requiem, detail, Knitted copper wire, 2019, Photo by Sjur Fedje

My next Solo Exhibition, in Galerie Maria Wettergren, Paris (February 8th – April 25th, 2020) will show the new metal pieces.

Comment on how your textile work can be related to your childhood and the local fishermen.

I was born on the Finnøy Island at the North Western Coast of Norway in 1948.

Finnøy Island, where Gjertude grew up

During my childhood there was an abundance of fishing of herring going on every winter. The herring were caught in large nets and hauled up in smaller ones. When the weather was bad, the harbor was packed with boats, and big bunches of fishnets were hanging out to be dried.

Every summer holiday I spent with my grandparents, living by themselves on the tiny Notholmen (not =net) island on Hustadvika. It is a famous and dangerous part of the Norwegian coastline; many ships have been wrecked along it.

Notholmen, where Gjertude stayed with her grandparents

In the evening, when the weather was good, I used to go with my grandfather putting out the fishing nets. The next morning, I would always wake up early, eager to see the nights catch. We used a rowing boat, and it was my job to maneuver the boat while my grandfather was hauling up the nets. Coming home, we worked on loosening the fish and crabs, rinse and hang up the nets to dry.

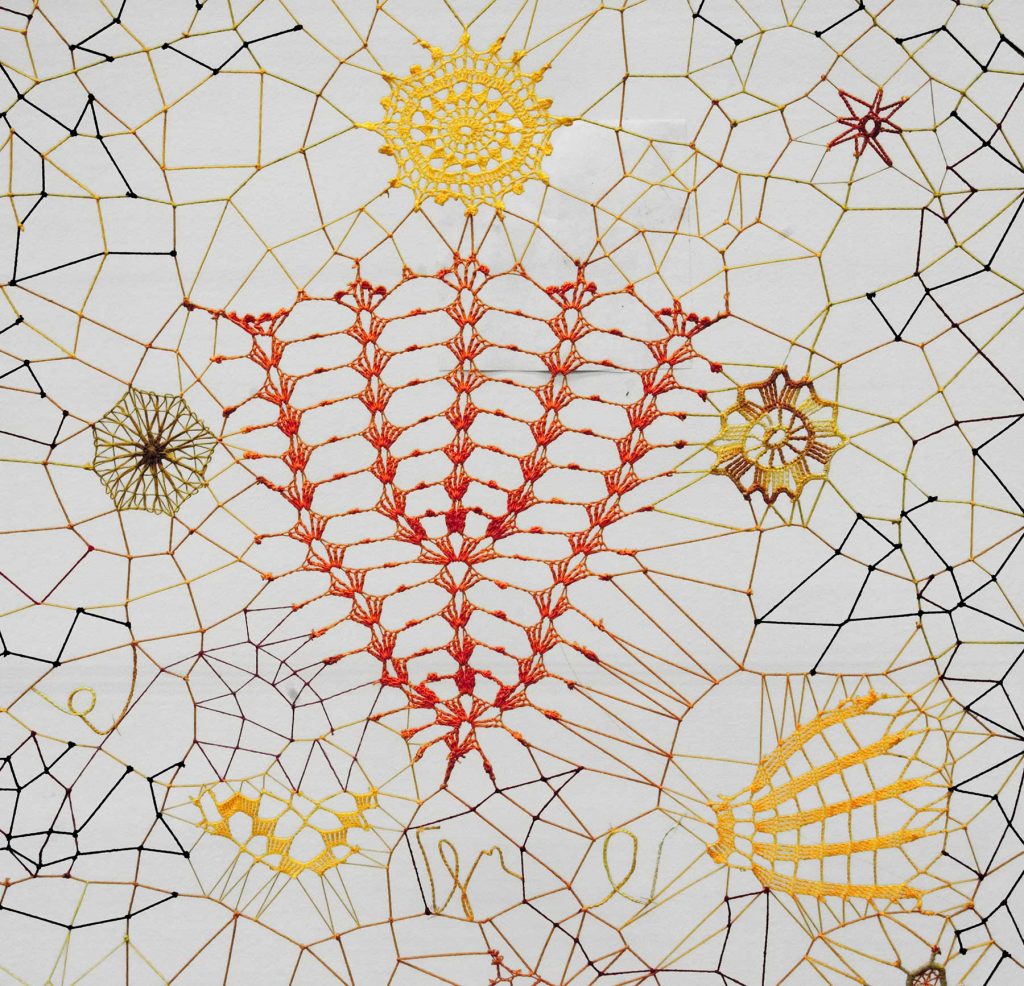

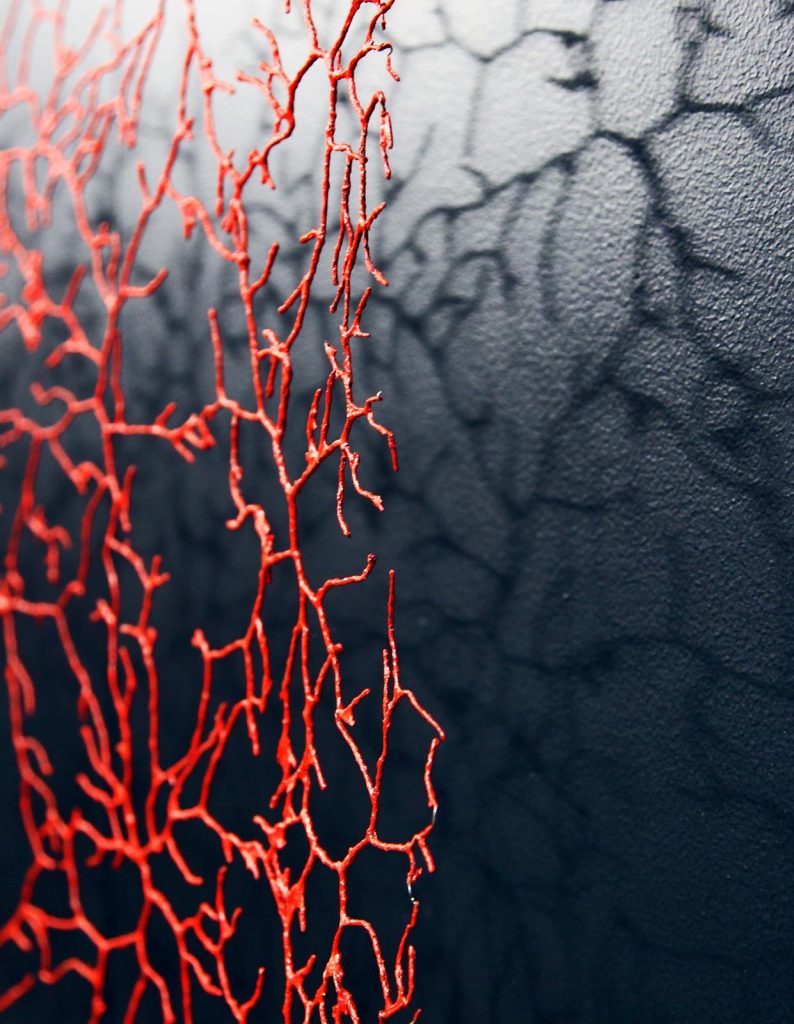

“The net” has thus been a central theme in my life and art from the very beginning. I am frequently using childhood memories, as in CORAL SEA from 2016: “When we were fishing with nets, sometimes big corals, we called them “sea trees”, would be attached to them.

Coral Sea, detail, 2016, Photo by Sjur Fedje

When they came up from the sea, they had bright yellow and red colors, that after a while would fade away. In my fantasy they were greetings from a mysterious world deep down there, colorful and fantastic, unlike the world we were living in.”

Coral Sea, 180 x 250 cm, Cotton and linen thread, glue, crochet knitting and various lace techniques, 2016, Photo by Sjur Fedje

Today scientists say that the coral reefs are highly endangered: huge coral areas have turned grey, also here at the Scandinavian coast.

What originally lead you from tapestry to Textile Art?

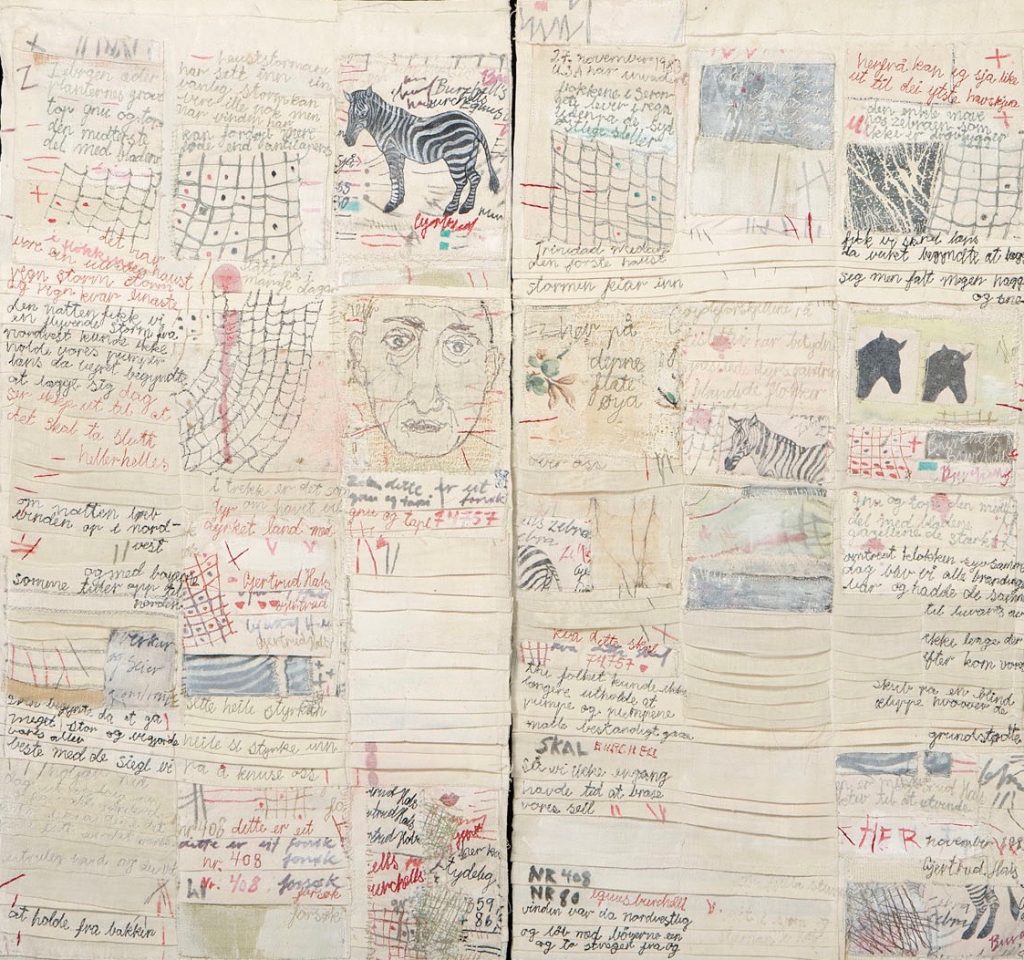

In the mid 70’s I had a desire to learn the craft of weaving, had two years of training in classic tapestry weaving and plant dying. However, I soon felt that for me it was too rigid, and I started experimenting with new ways to use the traditional craft. Gradually I also used other techniques and materials, amongst other I made a series of LETTER FROM THE ISLAND, embroidery made by hand and sewing machine.

Letter from the Island, 1983, Photo Nanna Wessel

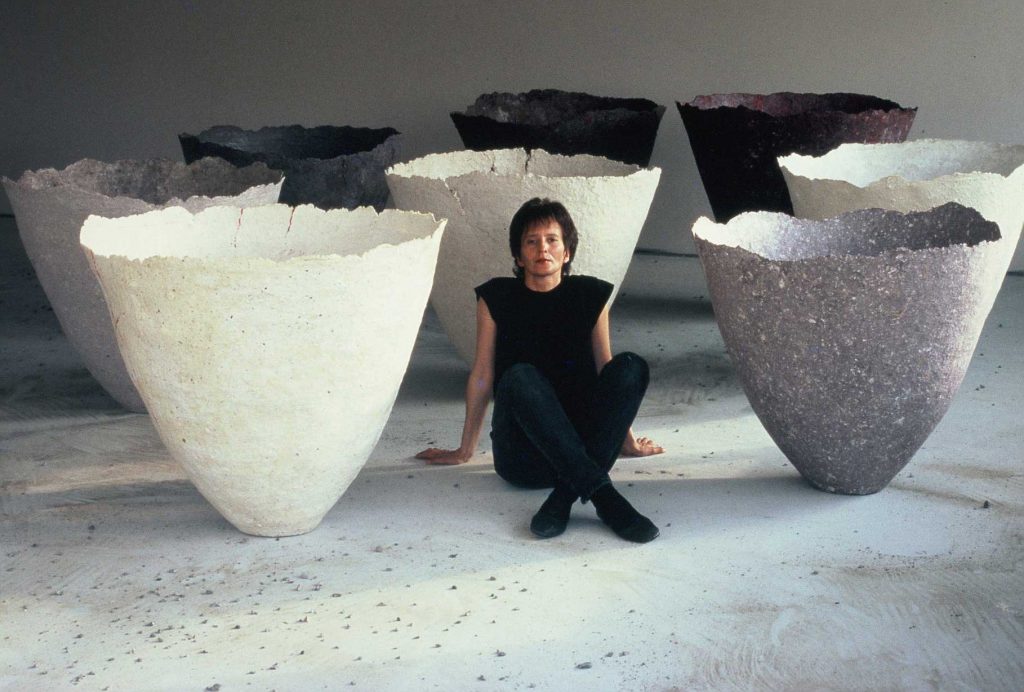

Still not content, I began, in the early 80s, trying out paper cast, as I had a vision of making fiber sculptures. After having been working in a tiny bedroom for some years, I in 1985/86 got my own spacious studio, and about one year later the first LAVA vessel was a reality.

Lava (group) 1987, cotton, flax, and cellulose fibres, paper cast, each piece 90H x 80 cm

Discuss your Lava Series and how this came into being?

When I managed to make the first LAVA vessel, it was after years of testing and failing. I had a vision of what the shape was going to look like; a membrane, a shell, archaic and timeless, huge, vulnerable and strong at the same time.

Gjertrude Hals, with Lava, 1987

I felt quite vulnerable myself at that time, having left my family for a period to study sculpture at the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art. Maybe the new surroundings helped to liberate the idea, because suddenly I succeeded! I knew immediately that I had found what I had been seeking, and after some months of building and testing different molds at the Academy, I went home to my new studio and started to produce the LAVA vessels.

Two different molds were built out of cardboard and covered with thin plastic. To build the vessels themselves, I used paper-pulp with cellulose glue, cheese cloth and old fishnets as reinforcement.

It was physically hard work, especially to prepare the material. In the beginning I used pre-cut cotton, flax, linen and cellulose fibers, blending it in a kitchen machine. Eventually I was able to buy a Hollander Beater, where I could cut my own fibers, making it a lot easier and much more fun!

The LAVA project went on for a year and a half, with totally about forty vessels.

During that period, I was looking for a suitable location for taking photos. I tried different places, also outdoor, but it did not give the right feeling. One day I came upon a half-finished house construction, and it was perfect!

My husband took the photos, and I thought it was important that I was posing with my artwork in some of them, to visualize the size of the LAVA objects.

There were three Solo Exhibitions with the LAVA vessels:

Schæffergården, Copenhagen 1988

Molde International Jazz Festival 1988 (with a dance performance)

Gallery F15, Moss 1988 (also with a dance performance)

And many Group Exhibitions, selected:

Metro Art´s International Art Competition , New York 1987(I. Prize)

The National Annual Exhibition; Oslo 1987

The Tactile Vessel, Touring Exhibition in USA 1988

Neo Tradition , Museum of Decorative Art, Trondheim 1988

Perspective on Paper, Lillehammer 1989

ITF International Textile Competition `89, Kyoto 1989 (Grand Prix)

New Norwegian Textile Art, Museum Of Decorative Art, Trondheim 1989

Splendid Forms, Bellas Artes Gallery, New York and Santa Fee 1989

International Biennial of Paper Art, Düren 1990

Nordform, art, craft, design and architecture, Malmö 1990

Ode de la coupe, Museum of Decorative Art, Lausanne 1992

The Lava vessels are to be found in several collections:

Museum Bellerive, Zurich (3)

Museum of Decorative Art, Lausanne (3)

American Craft Museum, New York (1)

Erie Art Museum, Pennsylvania (I )

Leopold-Hoesch Museum, Düren (9)

The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo(3)

The National Museum of Decorative Arts, Trondheim (1)

Arts Council Norway (1)

Bob Kelly Gallery, Gothenburg(1)

Daiichishiko Co. Ltd , Kyoto( 9)

Besides that, they are in a few private collections, I have also kept some for myself.

How and when did you know that you needed to move on from this vessel?

As one can see from my CV, the years from 1987-90 were very active. Besides sending the artworks, I also went to many of the places I exhibited, f.ex. in 1989 I was twice in Japan, in New York and other places in USA, as well as in Norway.

This was before we used internet, and the communication from my hometown to places like Kyoto and New York was challenging. I remember I bought myself a fax machine, but it did not help much on the situation:

With three children and a husband working full time, I realized that the LAVA success was about to ruin our family life. Because of all the administration and traveling, I had almost no time left to develop my artwork, and by the end of 1989 I was exhausted…

One day, while my son was using the water-hose, I told him he could flush the LAVA molds as well… He did so, and we dug down the remains in the garden.

This might sound like a drastic thing to do, but this act marked that “enough is enough” and gave me the timeout I needed. It prevented me from being tempted go on and on. I had no molds any longer!

Little by little I regained my health and could continue developing other projects.

Ultima, in the water, photo Gjertrude Hals, 2018

Eventually, twenty-five years later, I made a similar mold for the ULTIMA vessels, that are made with cotton thread and resin.

Ultima, 2018, 90 x 100, and 80 x 90, linen, cotton threads, knitted mesh, resin cast.

Discuss the importance of Magdalena Abakanowicz and how her work has influenced your work.

When training in drawing/ graphic art in 1971-72, I went to Poland on a study trip. I had heard about the “Polish wave” in textile, at the Art Academies in Krakow and Warsaw, I saw some examples. However, it was first in 1976, with a major exhibition of Magdalena Abakanowicz

art in Oslo, that I was hit by the wave: the “Abacans” hanging from the ceiling and the hollowed-out, headless human figures on the floor made a strong impression!

Like my heroine I wanted to express myself, but what was there for me to express? I was not, like Magdalena, living in a repressing regime, that I understood was much of a background for her art.

I realized that I had to find another way, being faithful to my own background and experience.

Although Magdalena Abakanowicz was my leading star in my early career, I think my art has always been quite different from hers. I could never think of doing something similar, that would be false.

Step by step; playing and working, failing and retrying, I was able to express myself and write my own visual poems. But the strong “wakening up experience” from 1976 will always be with me!

Why have 2D and 3D textiles, become so much a part of your presentation of textiles?

Interested in the empty spaces/ the negative spaces, I am working with the connection between form, light and shadow. For me lightness is an important quality, often combined with sizes and shapes that normally are thought of as massive and solid.

My artwork tends to blend into the environment, where the “spaces between” are playing an important role.

F.ex the 2D textiles should always have a distance to the wall, that will “waken them to life”, with changing light, movement and shadows.

The way the artwork is installed in the room is for me decisive, and I remember from my study days that I was intrigued by others that were not aware of, or did not mind, how their artworks were presented. As for the tapestries, I also disliked that there was a front and a back side. I soon started to make the weavings transparent, installing them in the room, to make both sides visible.

Insula, 200 x 300cm, Metal, wire and paper pulp

Comment on ‘Insula’

Insula, detail, 200 x 300cm, Photo Gjertude Hals

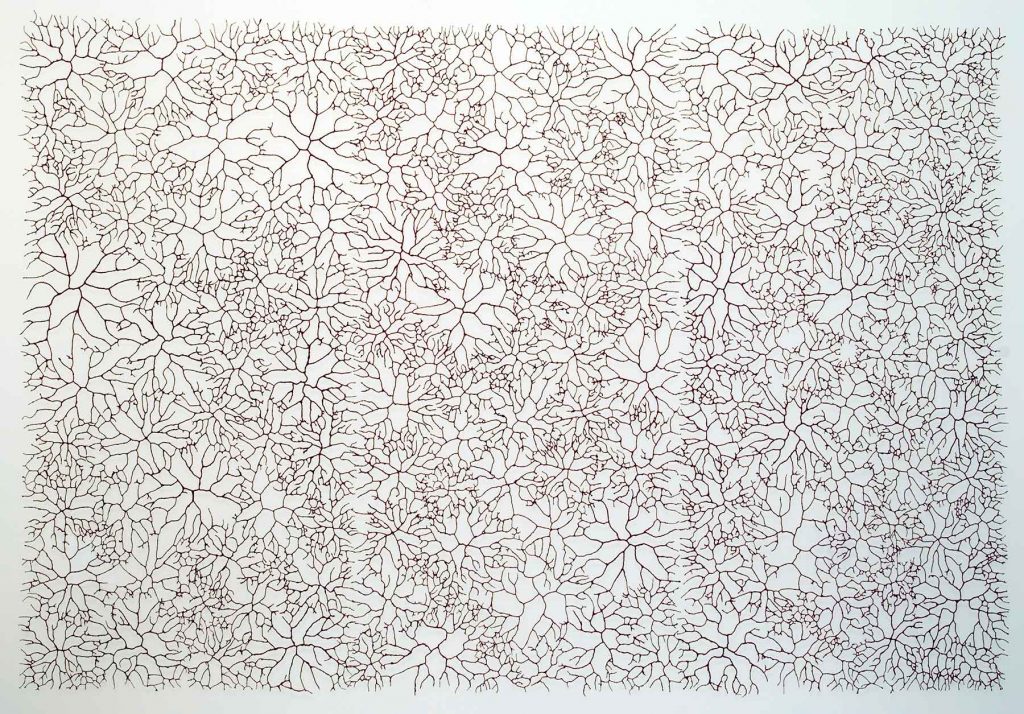

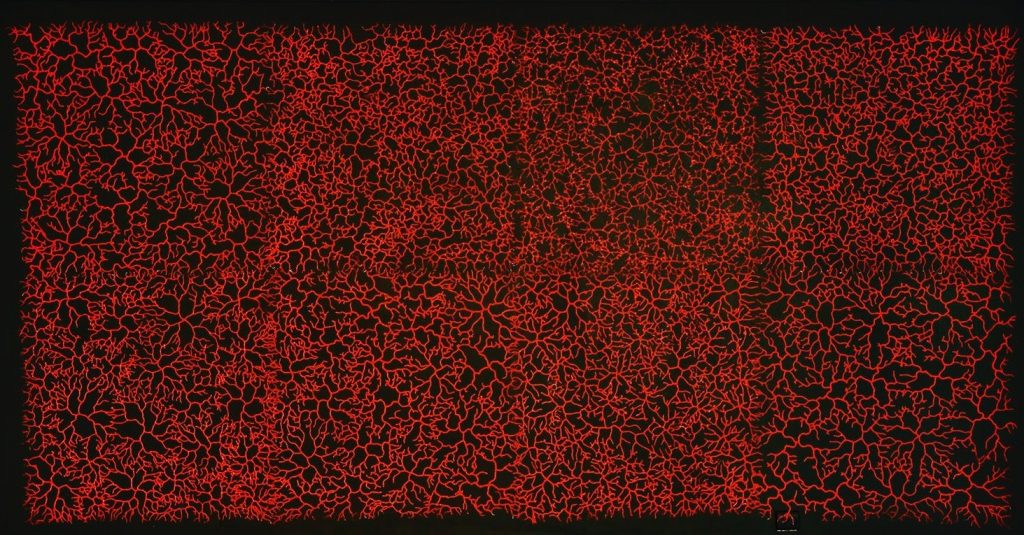

INSULA, that I look upon as one of my central artworks, was developed through a period of two years, 2006-8. In the beginning I called it FROM VESALIUS, referring to the 16th century Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius, well known for his anatomy drawings in “De humani corpus fabrica”. I was trying to make an arterial system, that I wanted to be an open structure. At the same time, it should allude an enclosed circuit; the circulation system.

My husband Odd is a psychologist, and since we met in 1970, he also, amongst other, has been my sparring partner. At this stage he was much into neuropsychology, and in this process, he came up with the term INSULA.

Insula, 200 x 300cm, Photo Gjertude Hals

I am always seeking symbols that encompass several meanings, so this was a deliberation: INSULA is the latin word for island, and it also may refer to Insular Cortex, a central structure deep inside the brain. It is believed to be involved with consciousness and plays a role in diverse functions, usually linked to emotions and perception of ourselves as isolated creatures, and to our consciousness of the “self”.

Insula, 200 x 300cm, with Gjertrude Hals, Photo Knut Fjeld 2008

At the same time INSULA has a reference to “the island” and a resemblance to coral reefs, another of my favorite themes. INSULA was made with metal wire into 100 x 100 cm squares, totally 9. The grid structures were sprayed with liquified, dyed paper pulp, about 50 layers. As one can see from the images, the artwork has been installed in different ways: with 8 squares, 9 squares, horizontal and vertical, and even once with a black background!

Insula, with Gjertude Hals, husband Odd, Photo Gjertude Hals

Discuss how you have moved from the world of tapestry and needlework to the world of textile art.

The tapestries I was making in the 70s and early 80s, for sure look very different from what I am doing today.

However, for me it feels like I never moved away from it, or any other artistic period of my life. It is all there! I go back to it in my mind, to «roundabouts» where I have been earlier.

Sorting through samples made f.ex. fifty years ago, might liberate a new idea! Every day I am using skills acquired through the years, using them in new combinations and sometimes, going in new directions.

How have you been able to use recycled materials in your work and the importance of recycling in contemporary art?

Fenris, detail, photo Sjur Fedje

Throughout my life I have collected items from the beaches and other places; shells and bones, bottle tops and textile fragments; materials that might otherwise be considered garbage.

As a teenager I made a series of what I called “material works” from objects found on the beach.

Fenris, detail, photo Sjur Fedje

About forty years later, the summer of 2004 I stayed for a month at Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. Wandering along the shores, I collected small items, everything from fish bones to man- made objects of metal and plastic.

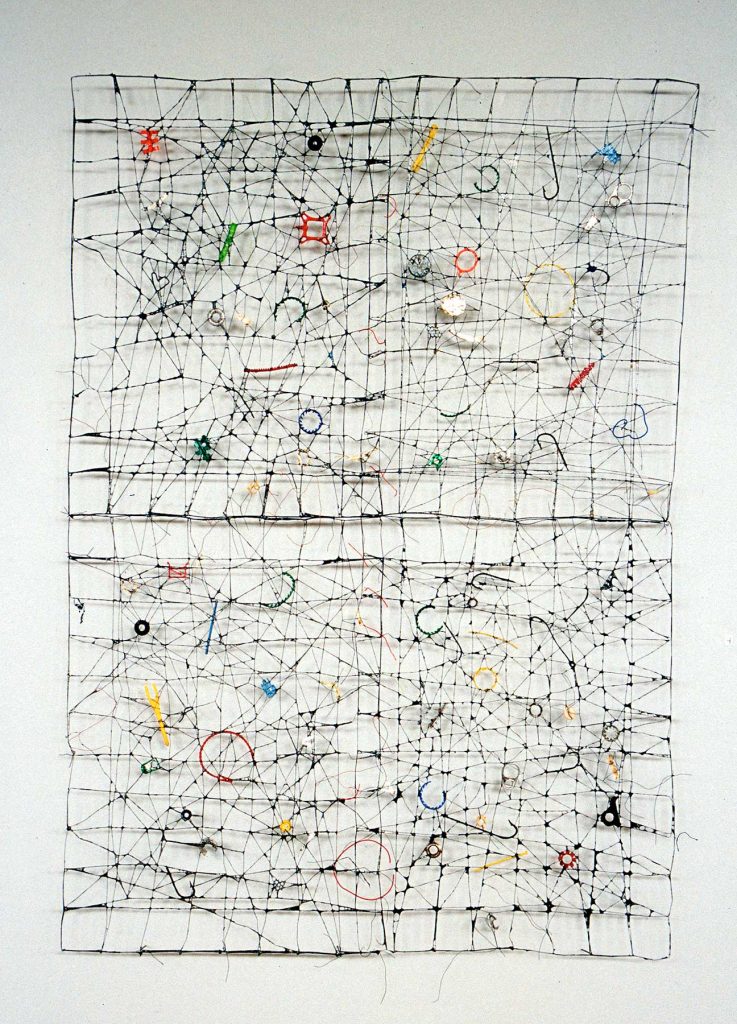

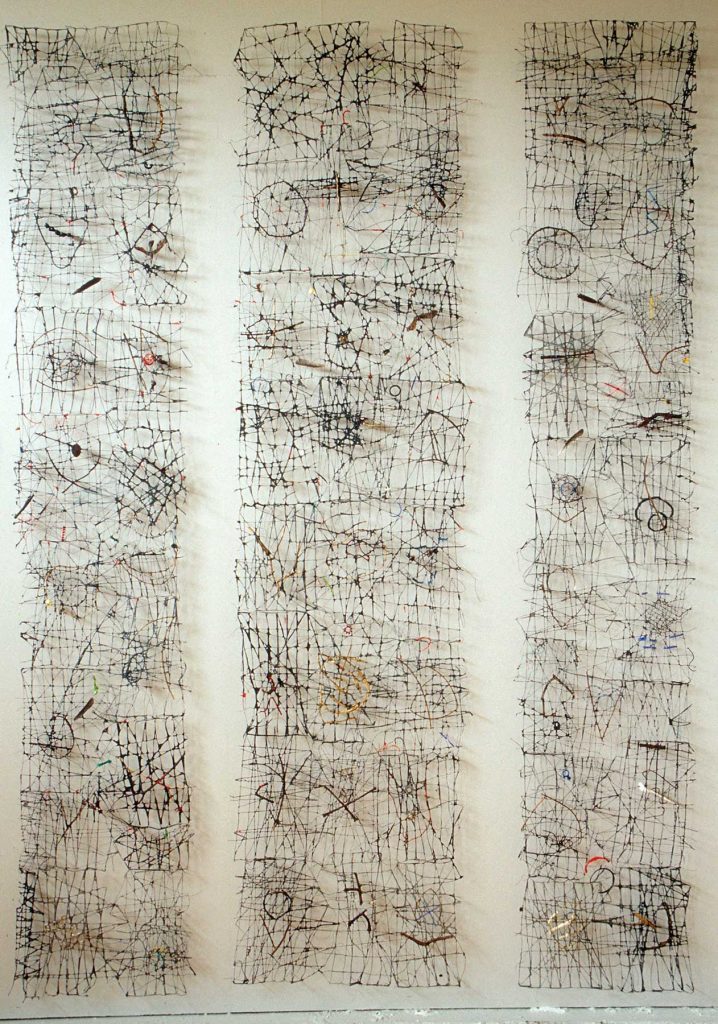

Kapp Mitra, 2005, 245 x 170cm, Threads, fibres, found objects,

Photo Nanna Wessel

They were integrated in my nets, as a new sort of “material works”, like KAPP MITRA, 2005 and FENRIS, 2004/06.

Fenris, 200 -06, , photo Sjur Fedje

Though environmentalism is an underlaying theme, I am not concerned with social morality when working with the trash materials, it has more with joy and creativity to do!

To use found objects, often used in a conceptual manner, has become quite common among artists today, I would say.

In this world of trash mountains and ocean gyres of plastic, many contemporary artists are in the front, battling what is happening to our planet. Some of my friends/colleagues have f.ex. formed the

“Guerrilla Plastic Movement”, where they are fighting for a plastic-free ocean by using visual, verbal and artistic means.

The importance of such activity should not be under evaluated. Artists have always been in the front row when big changes have taken place, as is necessary and inevitable in today’s situation!

Contact:

Gjertrud Hals

www.gjertrud-hals.com

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October 2019

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: