Fiona Hiscock Ceramic Artist

Are all the native Australian birds on flora that is specific to the bird’s habitat?

Yes, I am really particular about composing the painting so that the birds are situated within their specific habitat. I do a lot walking in parks and wilderness areas, and make close observations of the bird life in the surrounding bush. It’s important to me that the habitat is presented in a botanically correct manner, along with the bird and/or insect life I’ve observed in real life.

How do you originally capture these tiny birds?

I make watercolours on paper of the plants and birds that I’m interested in capturing so that I can work out how to paint them on clay. I take a lot of photos of plants and refer to these as well as my sketch book when painting the vessels. I also look at resources such as e-bird which lists species in particular habitats and provides really great photos for identification purposes. I also have a good pair of binoculars and a good reference library of bird identification books.

Discuss the shape of many of your jugs and bowls and their early colonial history?

As a kid my parents loved visiting antique shops, and in addition, I grew up in rural Australia. We had old sheds filled with tin and aluminium objects and I was always drawn to the large, utilitarian basins and bowls designed for faithful service to people or their livestock rather than fine China. I loved those old washing tubs, oversized water jugs, mixing bowls and buckets and feel they are reference to my history as a white non-indigenous Australian. They also loosely reference women’s labour and were an easier entry point for me as a female artist.

Can you explain the artistic process of your work?

I didn’t immediately go to art school at the end of year 12. Instead, I studied Fine Arts at Melbourne Uni and did a double major in art history. By the time I commenced studying ceramics at the end of my initial BA, I was completely versed in just about every art movement from the Renaissance to Modernism. When you know this much about art history, it can be very difficult to know how to locate your own practice. Starting with ceramics was actually an easy choice for me. It’s what I had really wanted to do when I finished school and it felt less overwhelming. I was very much drawn to making useful, somewhat humble utilitarian objects.

The key though, given my art history studies, was an interest in narrative, and I always wanted my ceramic objects to act as a canvas, or a device for story-telling and painting. This meant flipping ideas of scale, and giving the object a presence or stature that meant it could not be ignored, or put away in a cupboard. I was also aware that most of the art history I studied described paintings made largely by men. Ceramics, however, speaks of the feminine. We tend to associate vessels, domestic objects and crockery with the home, and by implication, with women. This felt like a better fit for me, and an entry point to a broader perspective.

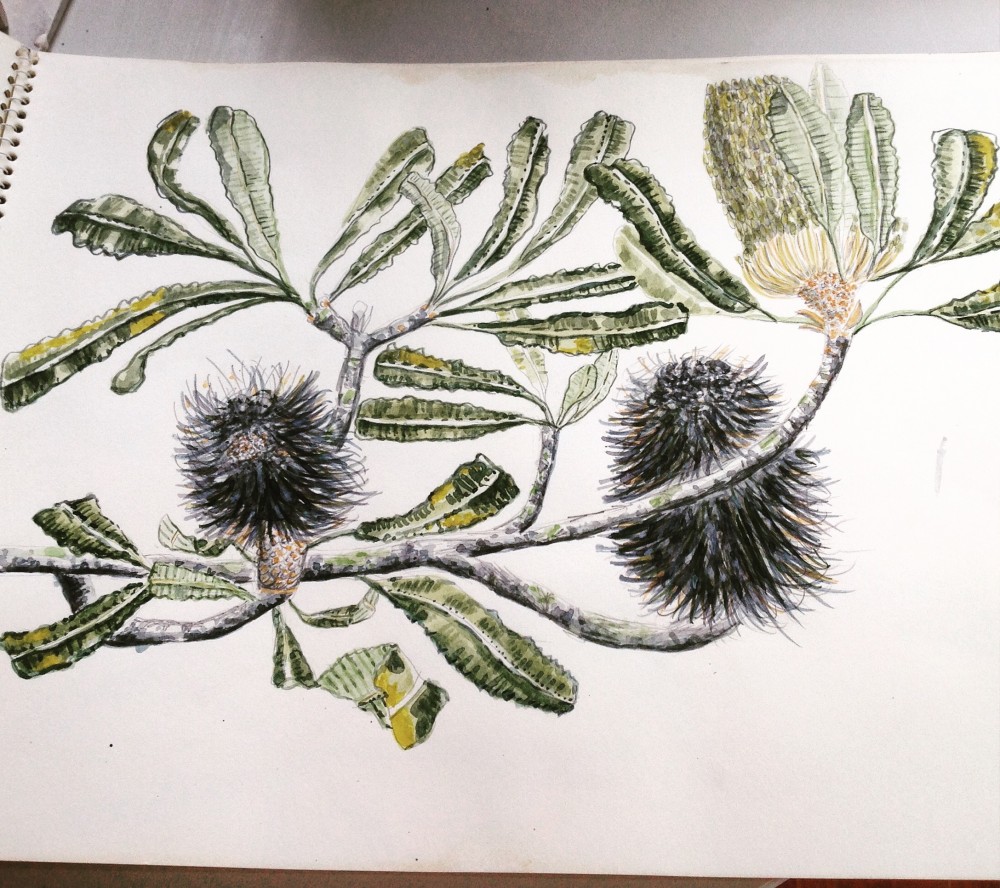

Earlier you also worked in watercolour – discuss

I have always made watercolour painting of plants that I’m interested in depicting as studies to support my ceramic practice. I don’t see myself as a natural painter and need to practice until I feel comfortable enough to commit brushstrokes to clay. Ceramic paints behave differently however – they tend to bleed and burn out at different temperatures, so there’s always an element of chance and unpredictability. I am never sure how the works will emerge from the glazing process, which to be honest, can be totally frustrating at times, and also surprising. I spend all our family holidays painting water colours, this is a really important part of my research and preparation, but they are like my reference library, and not intended to be exhibited.

Comment on the importance of your work and the impact the environment is facing.

My work has been about plants and the animals who cohabit with particular species, for the last 20 years. Growing up in rural Victoria, in an old goldfields house, I was first interested in painting the plants early settlers or colonists brought with them to Australia, plants deemed at that time, necessary for survival in what was considered a harsh environment. I quickly became more interested in the weeds that accompanied those species, particularly noting in times of drought that the weeds were thriving and changing the Australian environment as they spread. As a white person, I didn’t feel that I had permission or authority to paint native species as I was too aware of my colonial past. A trip, however, to a well-established Banksia woodland along the East Victorian jolted me awake, and I started to get heart palpitations encountering Banksia Serrata for the very first time. The irony of this personal discovery wasn’t lost on me – it was after-all, the first Banksia ‘discovered’ and identified by Joseph Banks, the London Botanist who was part of the Endeavour in 1788.

At this time, I was about to turn 50 and I knew I had to obtain permission from the traditional owners of the land before I could start painting their plants. I travelled and stayed with a very remote Yolnu community in the Northern Territory as asked the women there for permission to get out my paints. They gave me five different names for their banksia, which looked a lot like Banksia Serrata but was slightly different in habit and leaf spread. The community picked armfuls of plants for me to paint during my time with them and I return from that trip unable to depict anything other than Australian species. So, I spend as much time as I can in the natural world. I walk, camp and observe particular trees of interest to me, and the birds and insects that live within the confines of a particular species. If feel it is extremely important for me as an artist to paint the Australian environment and highlight its beauty and value at a time when it seems increasingly under threat from land clearing, drought and fire. I’ve also seen at firsthand how traditional Aboriginal cultural burning practices are much gentler and effective as an on-going management technique, and able to bring a better balance to a healthy ecosystem.

Where do you go for your inspiration?

Basically, the natural world.

The importance of residencies to your work

As an artist I believe it’s really important to take yourself away from your usual environment from time to time and observe new areas. It’s something I’ve missed greatly during the pandemic, and I’ve had number of trips cancelled due to Covid-19.

Early in your artistic work you had two residencies at Hill End in Victoria, Australia. During this time your work reflected Australia colonial pasts discuss.

Hill End:

I completed two artists in residencies in Hill End because at that time, I was interested in early colonial species, and I knew that Hill End had existing gardens of plants and trees dating back to early settler contact. I painted the trees that were commonly found in everyone’s gardens – figs, pears, almonds and other fruit trees.

I was there in two different seasons as I wanted to see how the trees reacted at different times of year and made a couple of series of work in response to that environment, all depicting introduced species. After this, I became much more interested in the weeds that arrived along with the intentionally planted species particularly as I was beginning to notice the effects of prolonged drought. Weeds such as rosehips (below cassoulet) and blackberries thrived when everything else was struggling to survive. This seemed like a good illustration of how colonisation had unanticipated, unacknowledged and often harmful effects on the natural landscape.

Now your work still has reflections of our colonial past but mainly in some the shapes of your vessels. Your work acknowledges modern Australia and your appreciation and knowledge of the need to look into our First Nations Peoples history and the land in a new open and honest way. Discuss also how exposure remote Aboriginal Arts communities has altered you art.

After working through the weed series, I started spending regular family holidays in National Park areas on Victoria’s east coast. Encountering the old growth banksia woodlands for the first time was immensely affecting and I knew I had to start painting and depicting Australia’s unique flora and fauna. I felt it was important to seek permission prior to doing this however, from our First Nation People and spent time with a remote community near Elcho Island in the NT, learning traditional weaving techniques but also painting local plants while there. The ladies provided me with traditional names for plants, often in 4 or 5 different dialects and would pick bunches of new plants for me to paint each time we went collecting materials for weaving. I’ve maintained connection with this community alongside a group of Melbourne based supporters and we have hosted the weavers on trips to Melbourne, and organised exhibitions of their remarkable work.

In addition, I have regular contact with a remote ceramics community near Alice Springs, the Hermannsburg Potters and have worked with them to explore our shared interest in depicting the unique Country we are all proud to live on and care for.

Current Residencies:

More recently, I’ve completed a residency in Bundanon, Arthur Boyd’s property on the Shoalhaven River to specifically paint and observe the local environment.

This area has an abundant plant and bird life and has been the site for traditional cultural burning practices, overseen by Uncle Victor Steffensen (Firesticks Alliance) to preserve, protect and nourish the natural landscape which is still recovering from years of grazing and a lack of Indigenous care.

Interestingly, in the 2020 bushfires, Bundanon was preserved as fire free and acted as a haven for animals to seek refuge thank to the cultural burning practices undertaken by Uncle Victor over the last few years, while the area around it was ablaze. I was interested in the biodiversity the area has to offer and was lucky enough to witness Uncle Victor practicing a Cultural Burn along with some, local young indigenous lads from nearby Nowra.

Discuss the Texture on the tops of your work.

I like to think of the tops of my work as a kind of framing device that contains the painting, which is why they will always have a decorative and repetitive pattern. There’s also a nod to the process of ceramics here and the tactile nature of clay, so I like the tops to be slightly freeform and organic.

Do you name each piece or is the botanical information included?

Each piece is usually named by referencing either location or the plans depicted.

Your work is currently in an exhibition, ‘I Am Here’ comment on this exhibition and other similar all women exhibitions and their importance on the public and young women artists.

This work was curated by Katherine in response to the Know My Name exhibition in Canberra at the National Gallery of Australia. Katherine selected 40 female artists she knew who are working today, across a number of mediums. This work was very personal for Katherine Hattam as she had made a number of paintings that included lists of the painters her female artist friends nominated as influential. The same names kept repeating and Katherine then started painting lists of female Australian artists into her canvases. I was extremely honoured to take part and agree with Katherine’s observations that female artists have been a tad underrepresented in major institutions. I welcome the efforts these institutions are making to redress this balance.

Contact:

Fiona Hiscock

@fionahiscock

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October 2021

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: