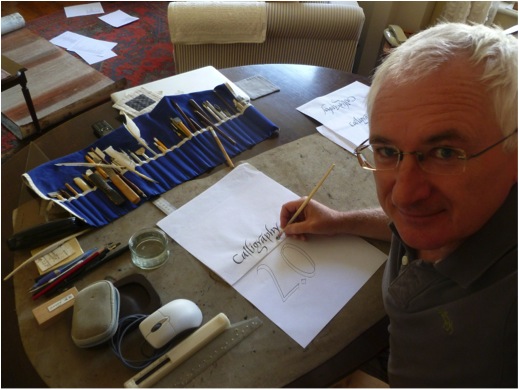

Ewan Clayton Calligrapher - Brighton, UK

It is hard to believe that as a small boy you had such bad handwriting. Discuss the implications this had on you at the time?

As a twelve year old it was impressed on me that my handwriting was a problem not simply because it was unpleasant to look at and hard to read but because it meant I would not be able to go to the school my parents had chosen for me. At thirteen I would have to take the entrance exams and because of my bad handwriting they were worried that I would fail. I was placed back in the junior class of the school, alongside the 8 year olds, to relearn how to write, it was very embarrassing!

On the flip side, your mother gave you a calligraphy set. Can you tell us how this was to alter your life?

It was the italic nib that did it, I saw that it was possible to make really beautiful letters, it was not difficult to do, and one could learn how to do it. But I was very lucky, I had been born near the village of Ditchling in Sussex. The calligrapher Edward Johnston had lived there. Today he is known as the man who revived calligraphy in the English-speaking world in the early twentieth century. He is also known as the designer of the famous London Underground typeface and logo.

My grandparents knew him (my grandmother used to go Scottish Country dancing with Mrs Johnston). She gave me a copy of Johnston’s biography to read. I was entranced, it showed me one could have an entire career involved with letters. With my new pen set I wrote out ‘’The Pen is Mightier than the Sword’ and swopped it for a 3d postcard – my first commission.

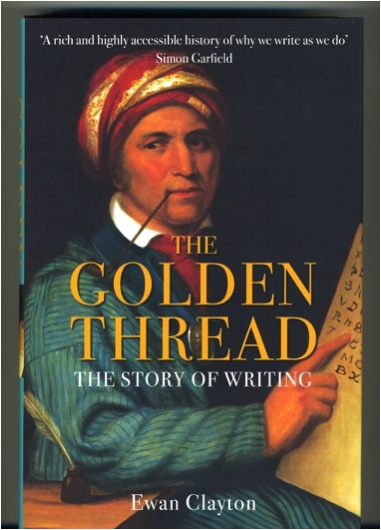

Can you explain what lead you to write your book ‘Golden Thread’?

I think the germ of it came to me one day when I was discussing calligraphy with the Libyan poet and artist Ali Omar Ermes. He was asking me about my tradition and I remember telling him it all went back to Roman Capitals and I described how various styles followed on – gothic, Italic etc. And then I asked him to tell me about his tradition. He said ‘I would have to start in a completely different place, I would show you the different aspects of society that use writing: the law, religion, scholars, merchants and then show you how certain forms of letters and styles of writing and documents were generated from those needs and communities’. I realised in a flash that this was a much deeper understanding of writing than my own community exhibited and realised this was the kind of history I wanted to write for the Roman alphabet.

Can you take one aspect, for example Book keeping traditions of the East India Company, and expand on the way this writing was done and why you have included this in the book?

It may seem paradoxical, for printing was invented in the 1450’s, but actually the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are key for handwriting. In these later centuries it was handwritten documentation that generated our entire financial system and enabled the spread of trading on a global basis. Handwritten accounts of the first-hand observations made by astronomers and early scientists also lay behind the whole project of the enlightenment. As Miles Ogborn shows in his book ‘Indian Ink’ (2007) the history of the East Indian Company provides us with a marvellous account of how this worked in practise. Worried that their employees would go ‘native’ in India and run their stations for their own profit, the Company developed sophisticated document keeping systems that made their employees accountable to each other. In the age of sail they managed to keep parallel sets of documents in London and India. The company’s expansion rested on the careful procedures they established for handling decision-making. This included a handwritten account of their meetings, displayed in public at each of the companies ‘stations’ for all to look at and signed after each meeting by each employee as an accurate reflection of their discussions. This is just one example of the continuing power of the handwritten document in an age often characterised as one where printing had finally triumphed over handwriting.

Discuss how important you feel it is to combine both historical knowledge and current technology?

The computer is a new writing tool in succession to the typewriter and the quill pen. It is a no brainer really. The future always develops out of the present, the present develops out of the past by understanding one we can have genuine insights into the other. Doing history is a thought experiment, just as is speculating about the future, both can inform the other. I believe however that this point is a wider one. This mixture is also needed in human communities at a social level, a community only of the young lacks something – it can literally burn itself out. A community only of the elderly is equally fragile but in a different way.

You have worked very closely with Xerox PARC and their digital communications explain this professional relationship?

The Palo Alto Research Centre of the Xerox Corporation invented much of the technology we take for granted today, the first commercial mouse, networked desktop computers, the ethernet, laser printers, the graphical user interface that we see on our laptops and smartphones. But because Xerox thought of itself as a photocopying company it never capitalised on these inventions. After the event the company realised it had to get a vision of itself that was non-technologically specific, so they came up with the idea of Xerox – the Document company. The document could be anything from a past technology or a future one, the company would never go out of date.

But then Xerox realised they did not know what a document was. So I came in with a lot of other people (anthropologists, linguists, philosophers, artificial intelligence experts, business historians etc.) to try and wrestle with that: what is a document and how we use them? I worked there of and on, on a consultancy basis, for 12 years.

Can you discuss how your calligraphy was picked up during your Monastic time?

In my late twenties I fell ill and when I recovered realised I had several unlived goals – one of which was to try life as a monk! I thought I would have to give calligraphy up but after a year the Abbot discovered I was a calligrapher and I got to work at it making large-scale work for the church, orders of services etc. The Abbot found out because his favourite sister came to visit and she recognised me, unknown to me she had once been the secretary of the Society of Scribes and Illuminators to which I belonged! My secret was out!!

Explain what being named the UK’s Craft Stills Champion of 2013 means to you both personally and professionally?

I was given this award for my role in the wider work of education in the crafts. Some years ago I was commissioned to write a substantial report on the state of the crafts in Britain which was used to guide the policies of the various charities set up by the Prince of Wales. The ideas it contained proved influential, they helped create the atmosphere that led to the establishment of an organisation for Heritage Crafts in Britain, a mapping of crafts across the country and various schemes to encourage apprenticeships in the Crafts. During the mapping exercise we discovered that the Craft industries combined are as financially important to the British economy as the British Petro-Chemical industry – this has given craft considerable additional leverage politically. Personally the prize came with money for training and materials. Japanese paper makers have been some of those who have benefitted from my spending!!!

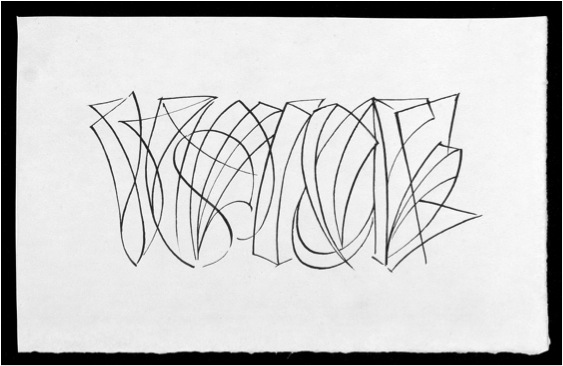

‘Voice’

“Voice, written in 2010 with a goose quill using sumi ink on Chartham Vellum handmade paper. I love trying to get depth in to the picture plane in various ways, here I simply use lines”

Can you explain the importance of Guilds in UK’s craft history and how you feel the decline of Guilds will effect crafts and art in the future?

I am not sure that Guilds are on the decline anymore, in fact there are various suggestions at the moment for a revival in Guild structures and training. Some Guilds, like that of the Goldsmiths in London, have been very innovative in their thinking in this area. Guild’s guaranteed standards in workmanship and they may yet have a significant role to play in this area. One fundamental of the guild system was apprenticeships, these too are seeing a comeback with government support in the UK increasing significantly. A while ago I heard one government minster talking of his dream that one day parents would have framed photographs of their sons and daughters getting their apprenticeship awards alongside those of their siblings getting their degrees. This is what we need, making things and skills to be as valued as concepts and thinking. For making IS thinking, under a different mode.

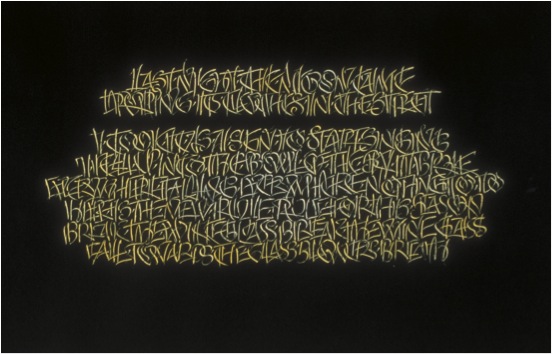

‘Sprachkurze gibt denkweit’ Jean Paul Richter

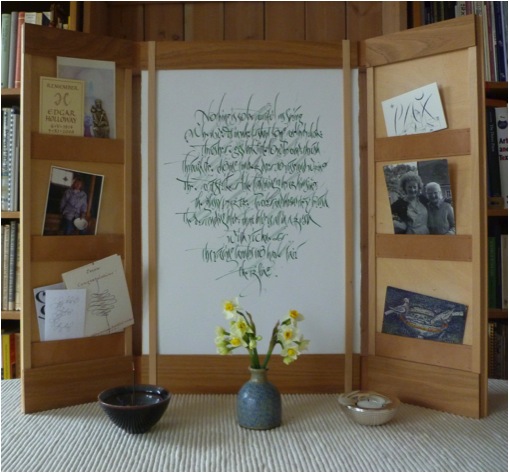

A poem by Rumi 1997. Written with a speedball pen and red wax in gouache on Black Arches Villin Noir. Rumi invented the whirling dance of the Dervishes. I wanted this piece to disorientate people as they read it. The work was a commission from the Crafts Council for their National collection

How many different surface has your calligraphy been applied to?

Vellum, paper, glass, stone, cloth, wood, ceramics, metal… but I would love to do something organic, something growing!

Can you share 2 of your works that have given you great pleasure?

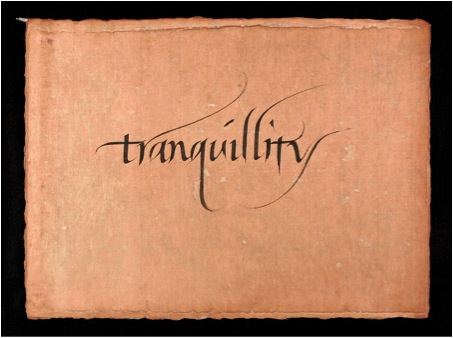

‘Tranquillity’

Written with a wood veneer pen on Kozo firre paper died with persimmon juice.

Tranquillity was written at the end of a long days teaching in Tokyo. The students had all left and I was alone in the classroom. I wrote the word about 5 times before writing this one. It was written slowly and peacefully and with a sense of continuous flow, none of my movements were hurried. I still enjoy looking at it very much. It is written with Japanese sumi ink, a pen made of wood veneer on Kozo fibre paper stained with persimmon juice.

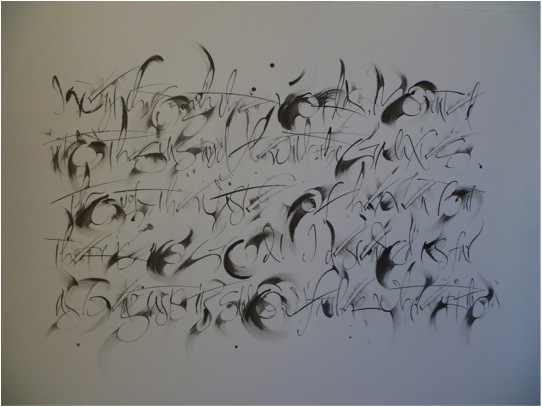

‘The Sermon of the Dead Christ’

This piece takes a rather different approach! It is written with a quill and the fingers and palms of both hands. The words are from the German Romantic writer Jean Paul Richter, the sermon of the dead Christ. I wanted to create depth in the picture plane, but to do it calligraphically, using just the tone of the ink that I smeared out with gestures from my hands the very moment I had written the stroke. Writing the piece was a performance, every gesture had to work and add up into a whole, there was no chance of going back. There was a real sense of having completed a journey with immense risks once done, the concentration had had to be enormous to complete it. Quill pen and sumi on Royal Watercolour Society paper.

Discuss your work with Calligraphy students from all levels, beginners to experts?

I enjoy teaching at all levels of experience and have done so now for nearly 30 years. I particularly enjoy working over a number of years with an individual, this is the most rewarding kind of teaching. I have been lucky enough to work in several places, the University of Roehampton and most recently with Sunderland University, where we could take students at degree level for several years. I have been concerned to make sure calligraphy has a place both at degree and post graduate level, to raise the status and intellectual content of the subject. But I also work with entry level classes so students have a really good start with some sense of what is possible from their very first day.

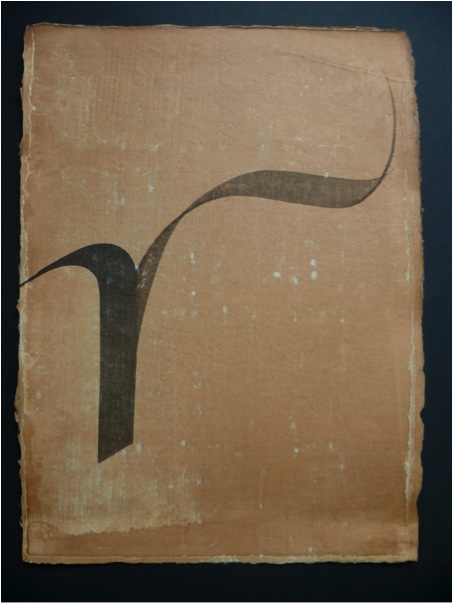

‘The Letter R’

The letter r, illustrating the first verse of Rummi’s Mathnawi.

“Listern to the reed, how it tells a tale complaining of separations.”

Your calligraphy has taken you too many different overseas destinations. Can you take one and tell us about that time?

Ah – there are really too many to choose from, but… the first that comes to my mind is that I loved teaching in the ancient monastery at Bobbio in northern Italy. It used to house one of the great scriptoriums of northern Europe and while we were there they held an open air film festival in the cloister with all the glitterati coming up from Milan. We worked in the old refectory painted with medieval murals. In the town itself there was an ancient roman bridge crossing the river (which people swam in during the lunch break) and when we needed to get more energy we could cross the street for a quick expresso. For the year following the teaching I enjoyed many dinners using the dried porcinni mushrooms that were picked in the mountain forests around the town and which are sold is large baskets outside many shops. I also bought my favourite jersey in the market place there. But then there is also Japan – which I have now visited eight times.

‘Last Night the Moon Came’

Discuss your signature?

My signature is nothing special, I guess the only distinctive part is the E which I like to write because it can be done in one swinging movement.

Can you explain your involvement with the Ditchling Museum?

Back in the 1920s, my grandfather moved down to Ditchling to become part of the Guild of craftsmen Eric Gill had established in the village. Many artistic people visited or lived there at one time including the painter Frank Brangwyn, the poet David Jones and the weaver Ethel Mairet. By the early 1990s all these people had become very famous but their work was being lost to the village. Two sisters, in their 80s, banded together to stop this happening, they bought the old village school and turned it into a museum. I had known these two women since I was a child and like many people in the village wanted to help them. At about the same time the Guild I was part of closed down and many of our precious things were given to the Museum. So over the years I have supported it. It has some of my earliest pieces of calligraphy in its collection (from when I was teenager) for the Bourne sisters would commission work from me even at that age. They encouraged me hugely. Today the museum has just been rebuilt and was one of the finalists in the National Art Fund’s Museum of the Year Awards.

In 2014 you were awarded the MBE. Can you explain the classification of the award and your feeling of receiving this honour?

Officially it is an ‘order of chivalry’, I am rather a lowly member, one up from the bottom!! But it was lovely to receive it. I won the award both for calligraphy and for my work with Heritage Crafts. It was a great day when I received it at Buckingham Palace in a ceremony presided over by Prince Charles. I could invite three guests, we went out to lunch afterwards. But then I had to dash to the airport as I was also receiving the award of a Golden Pen, the first Karlgeog Hoefer Prize, the next day at Offenbach in Germany. I left my guests eating the desert.

The presentation of the Kalgeorg Hoefer Award to Ewan Clayton

Your book ‘Golden Threads’ describes the history of the word. Could you give a description from a much closer and personal level, the way your father’s letters to you and your siblings can show how technology has changed the way we write?

Yes my father has written a letter to all of my five brothers and sisters every Monday for 47 years. They began on small sheets of notepaper with the address printed in type in the top right hand corner, then he moved to A4 size sheets on a type writer using carbon paper. Then, when the local library got a photocopier, he copied the original (which my mother corrected by hand) and we got personalised photocopied sheets. Today they are emailed from his Mac. For his 80th birthday we gave him a digital movie camera so now we sometimes get images and short films as well! He has had to master a succession of technologies in his life in order to remain literate. This is true for us all and indeed has always been so, what it means to be literate at any one moment is constantly changing. Just today I had to check I had the correct postage for a card I wanted to mail (the rate had recently changed), I helped my Dad sort out a new virus on his computer that was blocking his email, I had to work out how to print out a licensing agreement for a typeface that I had to initial and then see if I could download a 1.82 gigabite file (on one computer I could and on the other I could not) and finally had to confront postal regulations about how to send some emergency prescription drugs to a friend in Tel Aviv – this is just one day’s experience of learning what it means to be literate in my world!

Contact details.

ewanclayton@btinternet.com

Ewan Clayton, Brighton, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: