Denise Boineau Painter - Florida, USA

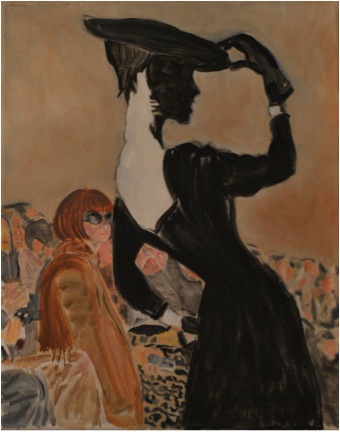

You have come from a fashion background, can you discuss ‘Vintour’, both the main frame and that ‘special’ viewer?

Two things make fashion designers (at least the ones I know) anxious and very anxious, respectively: mention of influences or predecessors and the front-row presence or absence (the latter is somewhat worse) of Anna Wintour, Vogue’s long-time editor. I have always been fascinated by silhouettes. I also have a thing for fashion icons and vintage designs. All of which help explain, at least in part, the painting “Vintour.” The composition juxtaposes fashion’s present and fashion’s past and sets the scene in an ambiguous spatial setting. We first encounter the vintage silhouette. Behind her sits Wintour, well-defined and fully filled-in. And behind her and to her sides the rest of the audience seems to dissolve into the background. I would have been surprised (maybe even amused) had I been in attendance. Anna? Always the professional: you won’t find out until the next issue..

‘Vintour’

In your work ‘Retro Chic’ you have added Blue. Can you expand on this technique?

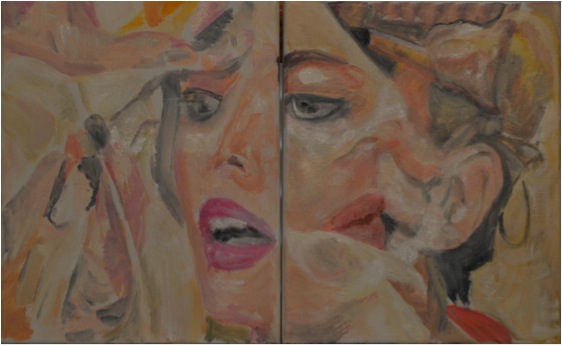

What do we see when we look at ourselves? What do other see when they look at us looking at ourselves? These two questions were the catalyst, of sorts, for “Retro-Chic.” The painting is a snapshot of a strong, confident woman, in mid-toilette, betraying her soft, feminine side, and a touch of hesitancy, possibly doubt. And between the lines, it is also a reflection on the aging process and the place beauty has within our own personal stories. “Old age,” Collet confessed, “is an uncomfortable piece of furniture.”

The toilette? You stand in front of a mirror—it is you and the dress. You look and imagine, and concentrate. You want objectivity. You remove yourself from the equation. The dress takes centre stage. But, in the end, it is you in that dress. You take off the black one, try the blue one on and you tell yourself: today, for this occasion, for how I feel, this outfit “works.” In a few years it may no longer work. And not necessarily because it has gone out of style, but because that older you, in that same dress, would be “trying too hard.” When you get back home, you may again stand in front of the mirror. You reassess, nod in approval, you may even gloat. That’s how the blue got into the picture—it worked on her and held its own against the ochre.

‘Retro Chic’

Can we discuss your equine paintings?

The people both as spectators and riders

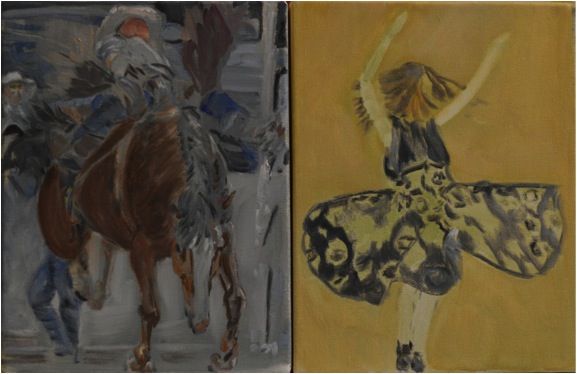

Let me begin with a recent painting “Takeoff,” which combines my interest in fashion and horses. The painting is really two paintings conceived as one. On one canvas a rodeo rider on a bucking horse holds on. The before and after involved a well-choreographed, reverse spooning between a very annoyed horse and a spat-waving, stylishly dressed cowboy. Behind him, the half-hidden body of a rodeo-hand leaning against the bucking chute’s gate, relaxed, maybe looking, maybe not. In the stands, a judge sits, subtracting points for style and keeping time. Somewhere in the stands across, I am taking it all in through a camera lens, thinking ahead. On the other canvas, an arm-waving fashion-conscious free spirit is in mid-dance. Her hair keeps up rhythmically, as it covers her eyes. Both the rider and dancer are self-absorbed; they do not inhabit the same space. But their bodies seem in sync.

‘Takeoff’

How do rodeo riders learn to follow the horses lead? How does the rider, in a millisecond, fall into rhythm with the bronco? What does the latter do to break that wave? I am not sure I know. But the relationship between horse and rider in “Takeoff” is very different from that in the polo and horse racing paintings.

Polo players

I came to polo through my love of horses, but also through fashion. In polo, the players, the ponies, and the crowd take fashion seriously. Aside from the clothes, what makes a good polo player? Strength, endurance, guts, good balance, keen eyes, a highly manoeuvrable neck, a sixth sense to keep tabs on their pony, and a special language to guide its every move. The ponies are also good athletes; the good ones know what they are up against and can anticipate.

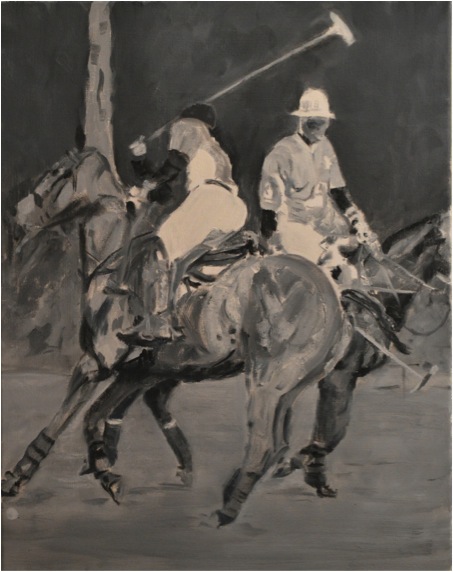

In “The Reach,” I tried to portray the inherent danger in a sport where players make split-second decisions while riding fast-moving ponies and waving long mallets. The player up front may or may not be avoiding the other’s mallet.

‘The Reach’

On the other hand, the painting “The Other Side” captures a deceptively leisurely moment, a gentlemanly, “please go ahead” understanding dictated by the rules of the game. Ponies and mallets capture the fact that nothing has really stopped.

‘The Other Side’

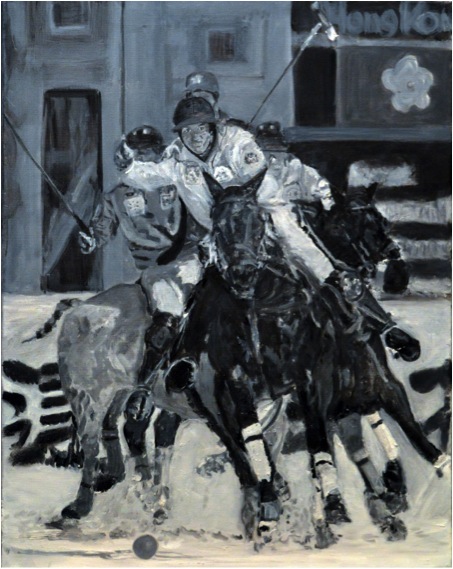

In “George Meyrick,” the ponies are charging right at the viewer. Meyrick is up front, teammates and opponents are in close pursuit, and hooves, when they are touching the ground, are in search of traction. It is moments like this that make polo an exciting sport to watch, polo players and their ponies special athletes and partners, and painting them challenging, but rewarding.

‘George Meyrick’

Where you combine both the spectators and the players

The spectator at the polo match, horse race, rodeo, or fashion show is there to look at the players: the riders, the horses, the clothes, the photographers, the press, the celebrities, the rich, the not so rich, the models, the cowboys, the designers, the entourages, and the other spectators. I am often behind a camera lens, which limits what I can look at, or defers it until a later time.

The players in “Palm Beach Spectators” face a crowd. Some of the spectators are attentive; others are not.

‘Palm Beach Spectators’

In “The Pass” the spectators are seated on the ground looking up. This was at a

Charity match and the spectators have a “this-is-a-nice-way-to-spend-a-fall-afternoon” kind of look.

‘The Pass’

Horse racing

‘The Edge’

The gates open. Horses gallop tightly in a pack; they bump and jostle. Jockeys keep an eye on the track ahead and on the horses that are gaining ground. In “The Edge,” the jockey turns his head ever so slightly towards the horse to his right, which is either pulling close or falling back. For this brief moment, it is their race.

“The Call” is about ceremony, history, and goose-bumps (I feel them every time I hear the call to post for the Kentucky Derby).

‘The Call’

You grew up on a farm and rode. Please discuss how this has influenced your equine work?

My mother bred and trained thoroughbred horses. From a relatively early age I was interested in the process of breaking in horses, getting them ready for a life with bits and saddles and riders. My horse, Chantilly Lace, and I had a special bond. I remember coming home from school and being dropped off down by the barn, where she would be waiting for me. I would jump on her bare back and ride.

In my equestrian paintings I try to capture the special relationship between the rider and horse. I sometimes find it helpful to visualize—putting myself atop the horse, eyes closed, so I can feel it in my gut. That’s what I did, for example, in “At the Gate.” I wanted to get a sense of what the horses feel when they are locked into the starting gate.

‘The Gate’

Many of your paintings are monotone. Please discuss this?

I lived in New York while working in the fashion industry. During the first few months, my senses were constantly overloaded, and my body and mind felt it. Eventually, senses become selective. You see yellow when you are crossing the street (survival first). You take in the sounds and smells as you make an evening out of it. The next morning you walk down the same streets, over the same grates, oblivious to the rushing subway underneath or the residual smells of the night. The same thing happened at work. After a few months, I could look at a rack of 100 dresses and see only the black ones, the blue ones, or the ones with patterns.

Beauty and glamour and grit and every other message we try to send when we put ourselves in front of others is about selectivity and stripping down (metaphorically) to the essentials. I think that is why I have embraced a monochromatic pallet. I say, I think, because I did not set out to do so. It felt right, at the time, for what I was trying to do.

In “Doppelgänger,” models back-stage are transformed so they properly “accessorize” the garments they will wear on the runway. The limited palette makes it difficult to tell where one model ends and another begins.

‘Doppelgänger’

You worked at Calvin Klein and learnt an important fact: “Colour matters only when you cannot make your point in black and white”. Can you expand on this in relations to your Horse/Man series?

Jockey silks are colourful—to allow the spectators to know who’s who. In “Chasing Diamonds” the silks are stripped of their colour, as is everything else. My aim was to emphasize the horses and riders rushing towards the viewer and their bunching up, given that they are forced to stay within the four corners of the canvas. By painting the diamonds in the leading jockey’s silk in black and white and grey, the ambiguity in the title is emphasized.

‘Casting Diamonds’

Can you discuss the importance of storytelling in your paintings?

I try to hide things. And leave bread crumbs—not all necessary leading to the same place. As with colour, I try to err on the side of saying less. In “The Return” a cowboy rides towards the viewer, and gets so close that his head no longer fits within the canvas. The horse takes centre stage. There is no background. There is no sunset. The horse looks like he can continue for another hundred miles.

Sometimes we reveal things inadvertently. Driving down to Miami recently I came across a sign at an RV park that said: “Stay the Night. Easy Hook-Ups.” Intended? Maybe. In “Gate Bound” the horse and trainer sport the number “9.” Is the rider on the right horse? A Freudian slip.

‘Gate Bound’

You say you paint “to share”. Can you expand on this statement?

When painting, I try to rein in my emotions, but not in the name of letting my brain do all of the work. Instead, I try to see the extent to which I can share certain feelings. I do so not necessarily to elicit identical feelings in the viewer, but rather to make the viewer’s first encounter with a painting mean something at a visceral level, before they try to start making sense of it in their heads.

My father would always tell me: “Give it to me straight”—a difficult task for a kid, and I think an even more difficult one for an artist. I do not want it to be straight—except for that initial encounter, and even then, there is not a specific emotional message that I am trying to share. I am not sure how successful I am at sharing, but I have found that I am more likely to be effective if I consciously try to keep my own feelings in check. An example, at least of the process on my side, is “Helios.”

‘Helios’

Can you explain where you get your inspiration?

Quite often it is from watching the interaction of people in their own relationships. I observe….I look for patterns. I find beauty and truth in many places. On being a woman artist: Camille Claudel. On being a woman: my mother. On seeing the top, even when you are at the bottom: Anna Wintour. On staying on top when others have other thoughts: same. On finding truth through a lens: Walker Evans. On finding puns through a lens: Man Ray. On creating coherence out of contradictions: Calvin Klein, who in 1981 made a splash by encouraging women to wear their Calvin’s au naturel, and in 1982 made even a bigger splash by encouraging men that they should invest in expensive underwear.

Your work is taken mainly from the ‘thoroughbred’ and high society; expand on this in relations to your art work?

We consume fashion and art, and in doing so we attach value to the specific objects we desire. And we are taught to desire them and to feel good about doing so. Piaget, Maserati, and Veuve Clicquot definitely want spectators at polo matches to pay heed. While all this is true, I am more interested in pointing at it, than at pointing fingers. (I would be unable to do so without pointing squarely back at myself.)

“The Match” takes the riders out of the picture altogether. The spectators at a polo match sit on the sideline, some watching attentively, a couple in the background, stand inside a tent, the woman looking straight at the viewer, or possibly trying to get the attention of the waiter charged with serving the champagne. In the foreground sits a stylish, possibly overdressed, but nonetheless glamorous woman. She sits higher, on a stool, most likely. She is sipping her champagne and staring into the distance, in a different direction from those following the match in earnest. These are obviously good sideline seats. The clothes look expensive; their wearers have the air of being able to afford them. Even the umbrellas have a custom-made feel. The champagne glasses are lined up, and another one is about to be served.

‘The Match’

You use the French proverb: “I seek and find wisdom in old French proverbs”. Can you explain the importance of this proverb?

It is a nod to my late father, who bestowed me with the name Boineau and made numerous pilgrimages back to the Dordogne is search of good water and distant relatives.

Contact details:

Email: ddboineau@comcast.net

Website: www.deniseboineau.com

Denise Boineau, Florida, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, January 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: