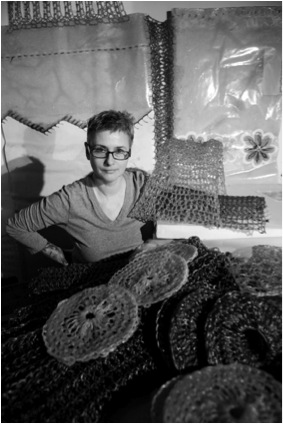

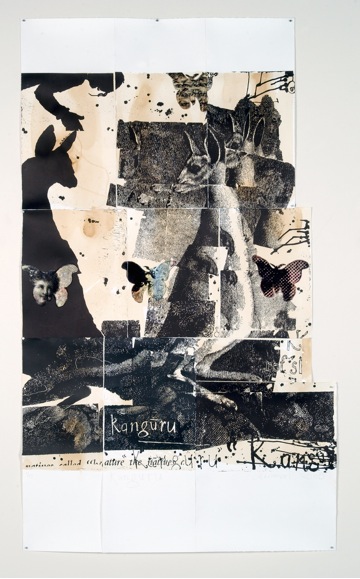

Yvette Kaiser Smith

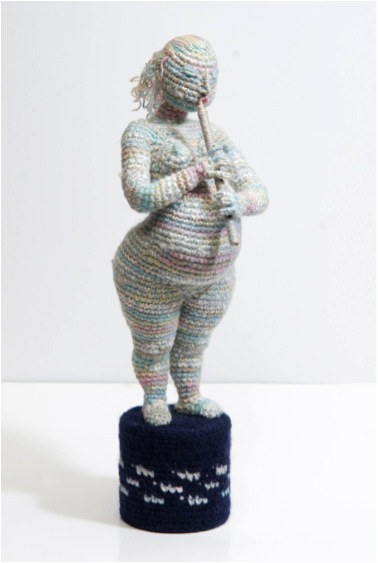

Can you explain ‘simply’ the technique you use to produce your sculptures?

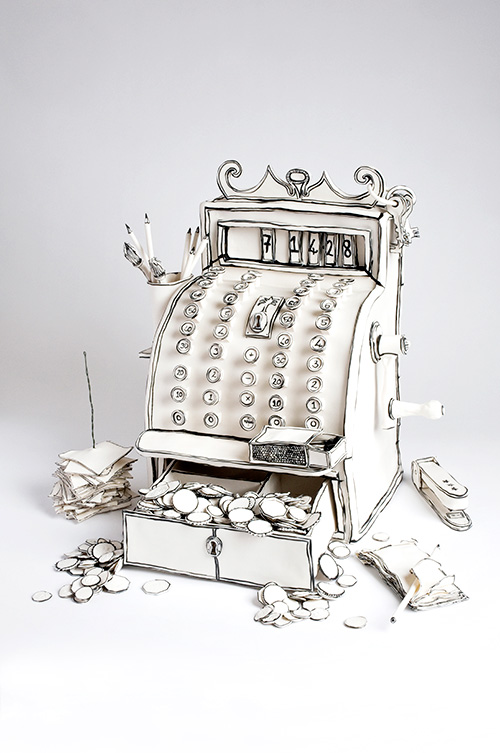

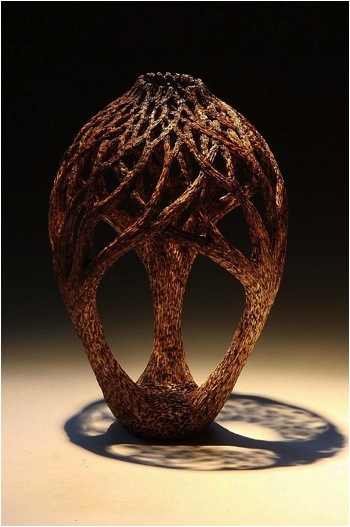

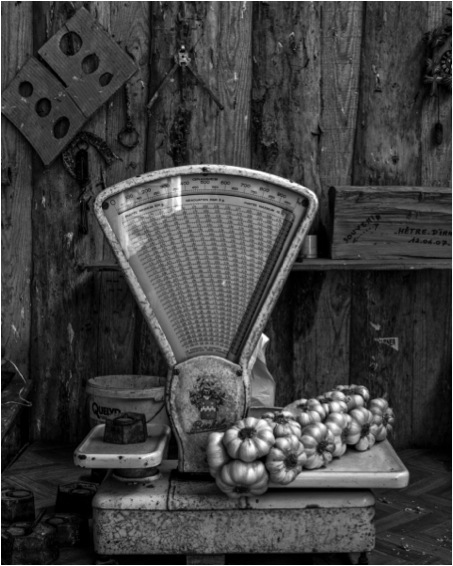

Fiberglass as a finished product is a fibre reinforced plastic. Fiberglass as raw material is a fibre made from spun glass. It is white, opaque, pliable, and behaves as a heavy cloth. It is commonly combined with polyester resin, a liquid plastic. Normally, the resin wetted cloth is laid into or over a mould until the material cures into a hard, translucent surface.

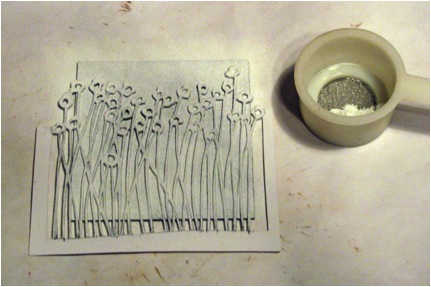

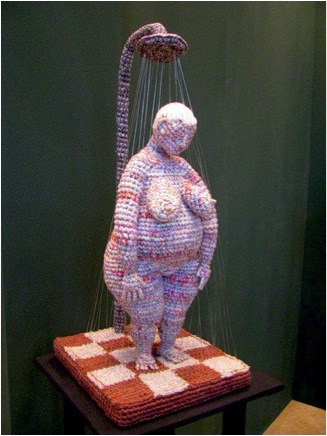

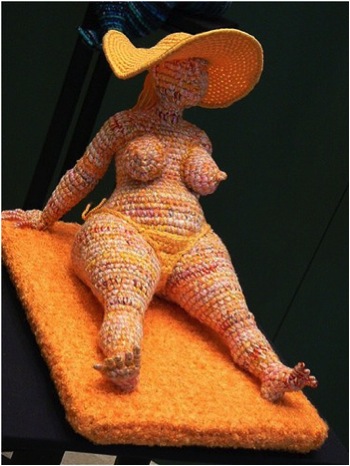

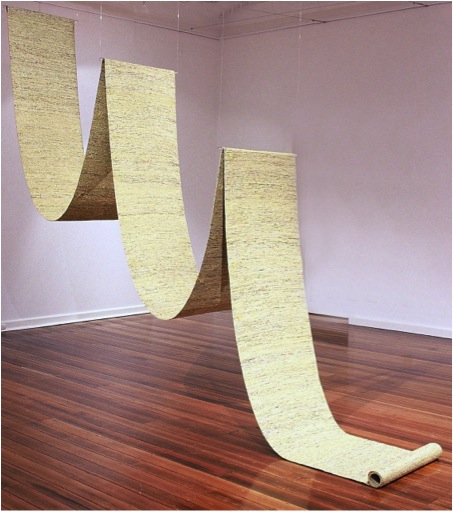

I start with a form of fiberglass called continuous roving or gun roving. Gun roving comes as a large spool of clustered continuous strands of fiberglass. I crochet the roving with a regular crochet hook to create my own cloth. The “J” hook is just big enough to pick up the mass of the roving. Using a variety of traditional stitches, I crochet flat geometric shapes: circles, rectangles, squares. For the next step, I use a hard finish polyester resin. This is polyester resin with 5% styrene wax. As the resin cures, the wax comes to the surface for a hard finish which is sand able, and eliminates the perpetual surface tack and smell of regular laminating resin. I do not lay my wet fiberglass into a mould; rather I use gravity to create simple geometric shapes. When laid into a mould, the crocheted cloth loses its dimensionality, it becomes flat and ugly.

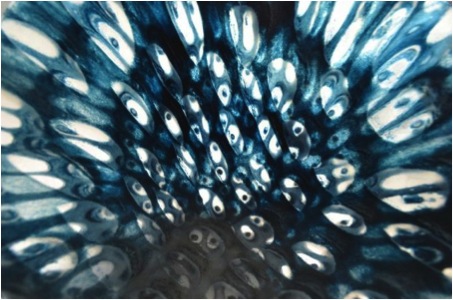

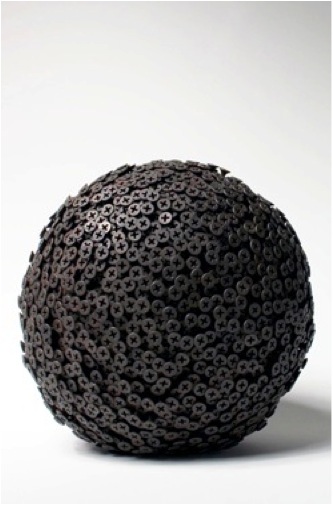

Fibreglass roving

Summary of process basics:

- • Commit to a number sequence

- • Work out form and colour in drawings

- • Crochet flat shapes

- • Build a jig for draping and forming

- • Pour out the resin, add colour in form of dyes, add hardener, apply resin to crocheted cloth with a 1” or 2” brush

- • Hang resin wetted cloth on jig and recover shape by gently pulling out the edges until it starts to set (between 15 – 30 minutes)

- • Let it harden for 24 hours

- • Cut the edges and make cuts to correct form

- • Sand body and edges of forms

- • Recoat with coloured resin, usually 2 or 3 times

- • Sand down drips

- • Touch up sanded areas with more resin.

If a work is made from several units that are fused together, I now have to:

- • Figure out how to make them fit and temporarily hold together in proper place with cable ties without going insane

- • Sew parts together with the roving

- • Apply resin

- • Sand

- • Recoat with resin

- • Polish with ArmorAll vinyl upholstery cleaner using a 1” brush.

Crocheted Cloth

Can you expand on the mathematics involved in your work and how this came about?

It started with Tim, my husband. Tim is a mathematician by education and a complete math nerd to the core. While driving me from install to install, during long highway trips, Tim used to amuse himself by working out the square root of the multi-digit numbers on the back of big trucks or by trying to deduce whether these long numbers were primes. Or while on vacation or visiting family in the country, Tim would drop to his knees, while all others walked on, to count the leaves on plant life new to his eyes; that number was always a prime. His constant curiosities made me see that math is a part of life, all of life, and cannot be separated from “identity” dialogue.

My reference to math started slowly with an obsession with prime numbers. Utilizing a unique number that is only divisible by 1 and itself was a natural addition as a conceptual tool within identity narratives. Whenever possible I pushed the number of components, or rows, or columns to the nearest prime number. I was convinced, and still am, that repeating nature in this way, that is, fixate on primes, produces a more balanced visual experience.

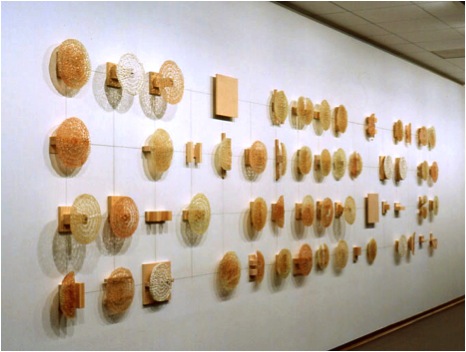

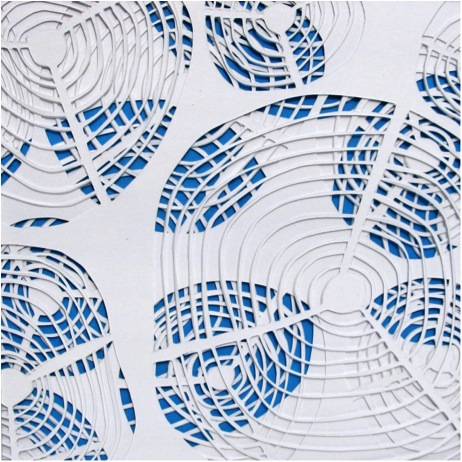

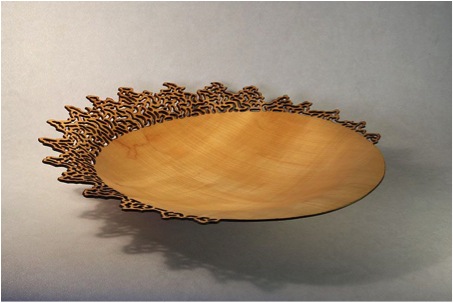

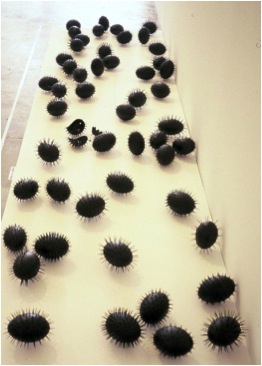

In 2001, I was working on a show for a university gallery. A wall sized piece takes 3 hard months to produce. I had 2 weeks left and one more large wall to fill. I crocheted 80 plus 10” circles and had the idea to make them ‘the same but different’ in the way that I am same but different from day to day. This involved snapping a graphite grid on the wall to control placement. (I love grids. I have always gravitated towards artwork utilizing grid, I just never found a natural way to bring it into my work.) I wanted to space the circles in a seemingly random, asymmetrical pattern. I asked Tim for a random pattern generator. He said: why don’t you use pi! I said: pi?! Simple interpretation: on the grid, 3 fiberglass circles, space, 1 circle, space, 4 circles, space, and so on. I installed the same piece in 4 different venues, always on a wall that was quite different from the others, I mimicked the wall proportions with the grid, so that I had something like 3 rows by 17 columns or 10 rows by 10 columns. Always I followed the beginning sequence of the infinite number pi, staying true to the number, and always the composition worked!! It was balanced, it was asymmetrical, it was not predictable, and it was beautiful. So now I am obsessed with prime numbers and using pi sequences to generate random patterns. From about 2000 on, most of the work was large and in one piece. Large they were but still limited by standard doorways in the short dimension; and both Tim and I were really fed up with moving these things. From the beginning of this ‘abstracting identity narrative’ stuff I depended on some level of narrative as the source for decisions about material, colour, form, movement, etc.. In 2007 I started working on a solo show for a new, beautiful gallery with a few very large walls. Like a 5 year old, I see a huge wall and I want to fill it. I planned a 10 by 10 foot square. This meant modules. In the thinking / drawing stage, one thing led to another and I thought: Articulate the digits!! Let the number make the work. Grid!! This gave the natural organic feel of the crocheted fiberglass a structure that was missing. And it really felt true in my gut. Everything since then has been number generated.

It was at this time I rummaged through my notes and found small scraps of paper on which Tim suggested, years ago, that I could also use e, another infinite number, and Pascal’s Triangle. I used pi, e, and Pascal’s Triangle to create all the work for the DIGITS show at Alfedena Gallery in 2008. Sequences from pi and e can produce completely different rhythms. There is nothing more true than maths and physics. If I commit to a number sequence, I stay true to it. If it doesn’t quite work for that particular form or idea, I try several sequences on paper until it does what I need it to do.

First Pi Piece

People hear math and run away. My math use is stupidly simple. The numbers are my referent, my source, the thing that creates the work. I am from Western culture so naturally I run sequences from left to right, top to bottom, with some exception. Larger works are straight forward, more obvious, interpretations of each digit, while the source math in the small works is less evident.

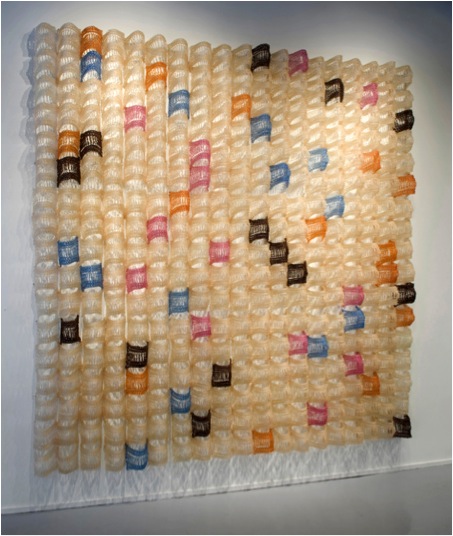

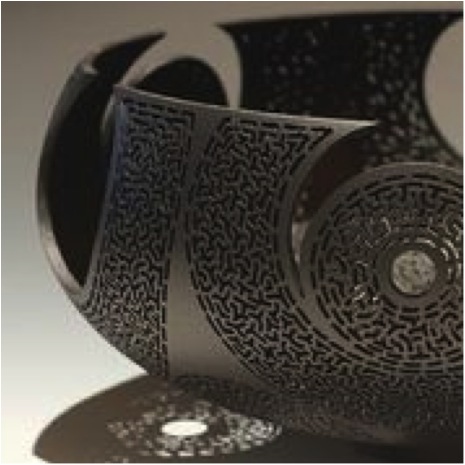

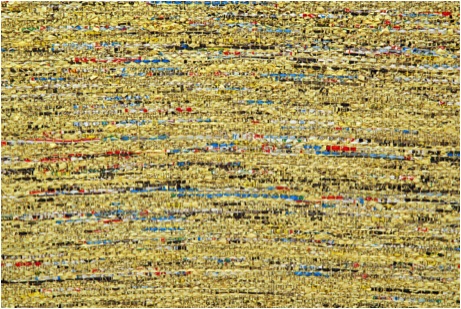

Identity Sequence e 4 (2007) is based on the beginning sequence of the infinite number e. It is constructed from 323 small units, 17 rows by 19 columns, to look like an enlarged section of a microscopic organic blueprint. Flesh toned units directly articulate each digit. The four molecule sequence of human DNA determined the use of four alternating colours which serve as the space between each flesh toned digit.

Identity Sequence e

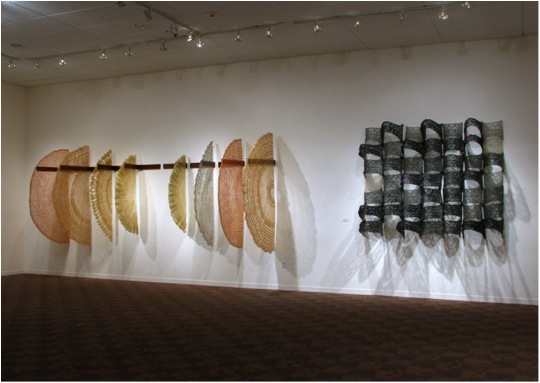

Identity Sequence e Black (2007) is based on the first 49 digits of the number e. I wanted it to feel like a small section that seems to be cut away from a much larger one. Grid is constructed from 49 units in 7 rows by 7 columns. Here the digits are articulated by two systems: tonal gradation of the black where the darkest colour value represents the 9 digit and no colour represents 0; and the distance each unit pushes away from the wall, where units representing the 9 digit push 32” away from the wall and the zeros barely pooch up.

Identity Sequence e Black

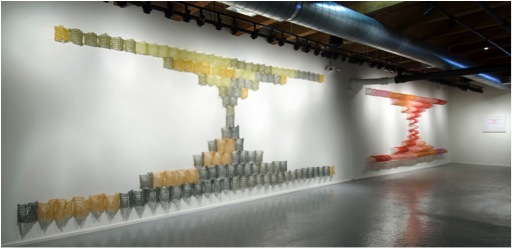

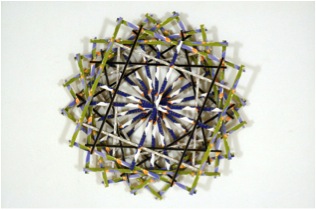

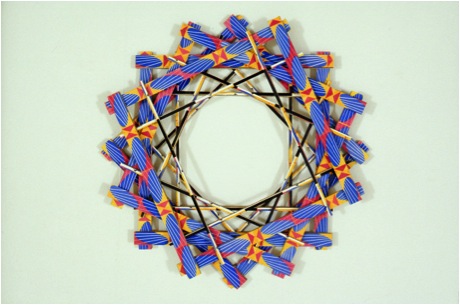

Identity Sequence Pascal’s Triangle Green and Red (2007 / 2008) are based on digits from the first six rows of Pascal's Triangle. Blocks of the same colour represent each digit. The form of each triangle in Pi in Pascal's Triangle Square and Pi in Pascal's Triangle Round (2010) is based on the first four rows of Pascal's Triangle. Four colours are distributed using the first 30 digits of pi. Meaning: I assign colour 1, colour 2, colour 3, colour 4, and then use the digit to drop the colour. For a pi sequence, I count 3 and drop colour 1; count 1 drop colour 2; count 4 drop colour 3; count 1 drop colour 4; and so on. Again, I run the sequence on paper in different colour order because the look of the work, in varied colour distributions, can be quite different.

Identity Sequence Pascal’s Triangles

Size - discuss the size of your work?

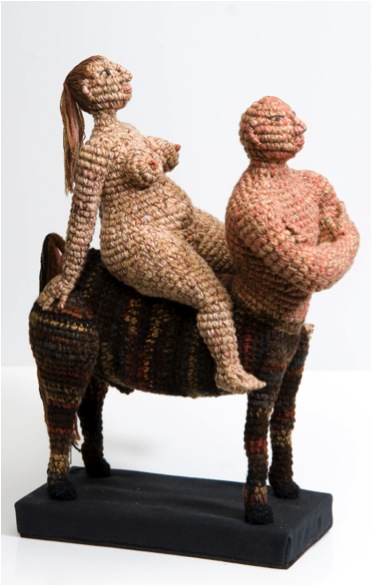

Early on, in BFA School I began to understand that every material and process has its own language, its own way to articulate words and ideas. This is one of the principle drivers that took the seminal “I want to abstract narratives of identity” question (1992) to the current crocheting fiberglass into abstract, geometric, minimal number generated forms.

Part of the challenge of understanding a specific material or conceptual language is finding the right scale for that particular form. And, yes, there is always the ‘right’ scale. This is why most of the work from 2000 to 2008 was very large. It took me years to find it and years to explore it. I still believe that the crocheted fiberglass language based on narrative needed to be in that large scale in order to be successful. The number generated work from 2007/2008 changed that. Grid came in. Modules came in. Small components came in. The older, more organic forms needed the scale. The structure of the geometry and pattern released me from that, although the first few number generated works are big.

Strands – small work 40x40x7

While making the DIGITS show, I ran out of time, had two small walls, the systems I was developing allowed for a successful 3 x 3 foot and 2 x 5 foot. Six months later I had opportunity to set up an artist booth at The Artist Project art fair. Small walls, actually thinking about selling the work, the new systems allowed and happily resided in this 4 x 4 and 3 x 3 foot scale. These things moved so I stuck in the scale. The work got a little bit smaller as I started using USPS to ship overseas.

Moving (selling and shipping) the work necessitated the scale down which would not have happened without the math structure.

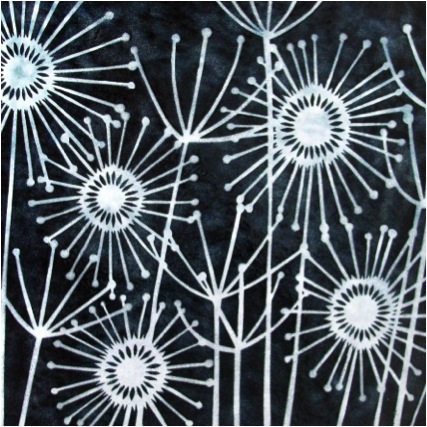

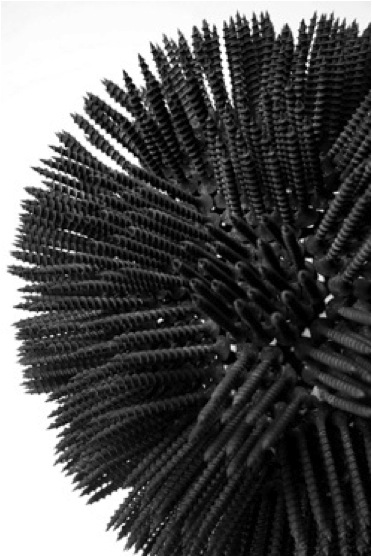

Part of the beauty is the shadows; your work casts comment on this?

At first, the shadow was just a by-product. I soon realized that the shadow, the act of being projected through a solid form, really played into the identity dialogues: which is you, the core of you, is it the body or that which flows through the body and imprints on your environment, that is, your behaviour or even a soul; that kind of stuff. And the shadows were cool. I saw some as drawings. Some had the look of photograms. I enjoyed the reference. With this new conceptual anchor, I wanted to create forms that maximized the shadow drawings, so that the expectation of a certain shadow reaction dictated the form creation and construction. Now that the forms work off of the numbers, a shadow of a curve anchored to a wall can serve as another dimension to complete or close a form. In the more architectural panel pieces, the shadows can draw out or elongate or even create additional elements.

Primary Structures

Discuss your involvement in the Art in Embassy Program?

Art in Embassies creates permanent and temporary art exhibitions in over 200 diplomatic venues worldwide. The temporary group exhibitions are curated by incoming ambassadors or their representatives, usually for the duration of their term.

A significant larger work, Daisy Chain (1999), was curated into the art loaned to Spaso House, the American Embassy in Moscow, Russia for a 4 year period (2002-2006). Also during that time, a smaller work was part of the exhibition at the American Embassy in Ankara, Turkey; this was a 2 year loan. From this exposure, in 2006, I was able to sell a large existing work to be a permanent part of the American Embassy in Abuja, Nigeria. And, Daisy Chain was the month of August in the 2004 Embassy of the United States wall calendar!!

Daisy Chain in Spaso House, Moscow

Comment on the connection between your work, culture and history?

The search for numbers went on for thousands of years; in this respect, numbers represent the human search for knowledge. And, just about every culture, current and extinct, has and had its own lace or knotted cloth tradition. The tradition of crochet and the process of crocheting both embody passing of time, human labour, and innovation and creativity. The narrative based crocheted fiberglass as well as the math driven crocheted fiberglass reference culture and humanness; they represent time and community; the work highlights our connectivity. If identity is a hybrid of our heritage, then lace is, as tradition of time, labour, and creativity, one tiny point of intersection that connects us all.

Your work, due to the base structure, is seen a feminist, how do you feel about this?

The base structure is the logic of geometry and spatial relationships created by number sequences, thank you for acknowledging the math! Oh, you mean the crochet!! Is the work feminist because I am female crocheting? If the same work was created by male would it still be seen as feminist? The work does surface gender issues, but perhaps not the expected. At most, I’d call the work quietly subversive. But I suppose subversive and feminist reside in the same house.

13 Pi Line - detail

It is seen as feminist because of the gender of the maker. I prefer for the art to be received for what it is: objects that are products of an active, long-term material and conceptual exploration; minimal, geometric abstractions that are not generic in form but resonate through specificity. The structure, form and colour distribution within the object is created by math; base materials are fiberglass and polyester resin, industrial and nasty to work with; the technique I use to create my own sculpting material is a craft traditionally attributed to female. That is one out of three key components.

I explore the nature of relationships and identity using formalism while striving for specificity. I began ‘abstracting narratives’ to go beyond the generic in my minimal abstract forms. Identity was a vehicle used to construct the DNA (specificity) of the initial work and then process took over. The work is not feminist, it is formalist and referential. It is a hybrid that defies conventional out-dated labels.

Crochet and lacework is very European does this connect you to your homeland and ancestors?

I was born in communist Prague. Moved to the United States 7 weeks before my 11th birthday. I don’t remember any experience with lace or crochet. In 1999, 30 years later, my Mom and I went back to Prague for the first time. By this time, I was crocheting fiberglass for about 3 years, the forms were on the large end of medium, I was not yet handling the material in the best way, I only used simple stitches, and my identity concepts were still limited.

The trip back home had a significant impact on my studio. What I saw was that Czechs are known for, and are proud of, the best beer on this planet, Czech crystal, and lace!! I, for the first time, realized that Czechs have a tradition of gorgeous lace everything. Every home we visited was inundated with lace: concentric circles on interior door glass; lace curtains; plastic lace on plant pots; lace runners; basically lace everywhere. On the streets, the old ladies seemed to have a sort of uniform which consisted of four items: blouse, slacks or skirt, vest, and shawl. Three of these were usually in pattern, the fourth was solid. This overload of patterns should not have worked but it did.

When I got home, my work exploded. Somehow, recognizing that my heritage comes with a lace tradition, I felt a permission to exploit it more fully. I also realized that, although I was claiming to “articulate narratives of identity in the language of crocheted fiberglass”, I was not utilizing the fullness of the crochet language. I bought a book that catalogues many of the traditional stiches, patterns, and formats and began to exploit this resource more fully. I learned that the more complex stiches created a stronger form and allowed me to work larger. While immersing myself in pattern, I finally began to think outside of the body and saw identity in terms of pattern: internal and external; nature vs. nurture; DNA; social behaviour, how groups affect the individual. The identity dialogue evolved into greater complexity. The sculptures reached their proper large scale. Reaching this scale forced me to develop better handling of the material. All this happened because I went back to Prague, saw lace, and reconnected to that culture and place.

Your work is sculpture: does it become sculpture due to its solidness or size? Please discuss

It doesn’t become sculpture, it is sculpture. Sculpture can be in any scale; it can be solid or hollow. Sculpture is not flat; it possesses mass and volume, as does my work. My forms hang on a wall but they reside in three dimensional space. The wall dependency began as a material / scale necessity and later became part of the material language. Sculpture manipulates and activates space. The sheets of handmade, not prefabricated, fiberglass are manipulated to create forms that break into three-dimensional space. The forms manipulate space by pushing into it, by holding it, by folding it, by squeezing it. Some of the forms are so active they command the entire room in deep three dimensional relief, Etudes from Pi in 5 Squared (2011) for example. Some quietly hover in shallow relief, like Pi Line 22 in 5 (2012), yet they still activate a shallow more personal space. In terms of construction, mine is both an additive and subtractive sculpting process.

Etudes from Pi in 5 Sq.

Which came first: the fibreglass or the crochet?

The fiberglass.

The ‘abstracting of identity narratives’ stuff began at onset of MFA School (1992). That work explored more common sculpture-student materials like iron wire, lead sheet, copper sheet, plaster, bees wax, wood. I was all over the place. My forms were restricted to body metaphors. I still did not understand scale. I had a copper sheet and iron wire form that did not work on the floor or in any relationship to the wall. As a desperate act to salvage the piece, I brought polyester resin, fiberglass matt, and fiberglass insulation into the studio to make a small stand. During my 1st year, a then 2nd year cast fiberglass cloth into moulds; probably why it came to mind. I knew immediately that fiberglass was the material to explore. Not only for its versatility but also for its natural translucency and skin like splotchiness.

Resin Applied Panels

During the next three years, my studio focused on material exploration, trying to understand the language of fiberglass and how to use it to articulate my conceptual agenda, which was still stuck in one individual, within the body. During this time, I found the roving. Having used iron wire in school for forcing a shape by binding, I bought a spool and began to play. It was all stupid. I shoved the roving in the corner and forgot about it.

Around November 1996, I was starting to work on my first 2-person show, my narrative was still limited to the body, dichotomies a large part of the dialogue; I was at an all-night grocery at one o’clock in the morning, running by the meat counter, from the corner of my eye, I saw tripe!! I stood there frozen in time as thoughts rushed through my head. I saw fat, I saw lace; beauty and ugliness; identity!! Without recognizing why, I associated lace with crochet. The next day I found a hobby store, purchased a book that teaches you how to make pot holders and baby booties, every size of hook available, and began to crochet. It took another 3 years or so before I began to understand the material language of crocheted fiberglass vs. the language of the prefab matt and cloth.

What are you working on currently?

I am making new work for a small solo show here in Chicago at ARTexhibitionsLink’s Gallery Uno that will go up the first week in October. Right after that I begin a 3 week Artist Residency at Ragdale. During the past 3 years, I have been trying to squeeze in time to transition to 2D by experimenting in ways to map the math via Encaustic work. This is what will continue at Ragdale; but my mind is already distracted by the possibilities.

Fibonacci

How do you physically cope with the resin process in you studio?

My studio has a large roof exhaust. I have a full face respirator with two options for filters; a great disposable glove supplier; my body is always fully covered; and at this point, it’s just a normal circumstance of my work.

Studio Basics – Wearing Resin Gear

It is the most maddening stage of the material process. With the time constraint of the initial curing time; the full gear I wear, especially in summer when it is 90 in the studio; the sticking to everything if in resin all day; trying not to lose 2 weeks of crochet in one day by not being able to control the form; this is what I call my Three Stooges stage because the resin session can easily turn into dark, one-person Three Stooges episode. If ever I scream in panic, it is in resin application.

It’s just part of the process. It is what it is. I am committed to this process, I believe in it. Much more unpleasant is the sanding!!

Originally your exhibitions were all in Chicago. This year 2012 you have an exhibition in Germany. How did this come about?

In late 2004 I went to a local gallery to hear an artist talk about her work. There I sat next to another artist who was actively working with ARTexhibitionLink, an art organisation founded by art historian Barbara Goebels-Cattaneo, which links the contemporary art scene in Chicago and Berlin. Barbara asks: “Do artworks show geographic or historical adherence or has contemporary art become a global issue, dealing with comparable problems, working with similar standards?”

In March 2005 Barbara was in Chicago; my new artist friend introduced me; I had a show up; Barbara liked the work; that fall she included me in a 3-person show (also featuring my new artist friend) that hung in an alternative gallery in Rome and later in Berlin. We reconnected in 2010; Barbara took my work to Berliner Liste art fair. In the booth across the aisle was Kunsthandlung Huber & Treff, a gallery from Jena, Germany. They listened to me talk about my work, non-stop, for 4 days. The following year Huber & Treff became the curators for an exhibition space in the lobby of Jenoptik Corporation in Jena which was unused for several years. They invited me to be the inaugural show.

A take away from this story is (although I am mostly a recluse) artists leave your studios!!

Jenoptik - Lobby

Artists are becoming global - can you expand how this is affecting your art work?

The shipping difficulty of moving sculpture in terms of cost and dimensional restrictions led to two things. It made me think in modules (the first work I made for ARTexhibitionLink in 2005) which pried open the door to the number generated work. And it continues to challenge me to make smaller, more compact, yet still somewhat intelligent works, which are easy to ship. I like barriers, they push the work where I would not go on my own.

When I travel, I, like many artists, take too many pictures, often of interesting colour combinations or patterns in architecture. Before each project, whether the fiberglass or the 2D work, I run through my sources for inspiration. Math is universal, but I think that the character of a specific geography can be transported through colour and/or rhythm.

Contact Details:

Website:www.yvettekaisersmith.com

Email: yvette@kaisersmith.com

Yvette Kaiser Smith, Chicago, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October, 2013

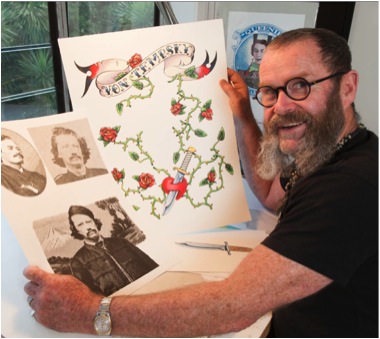

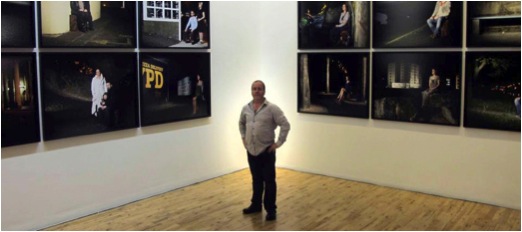

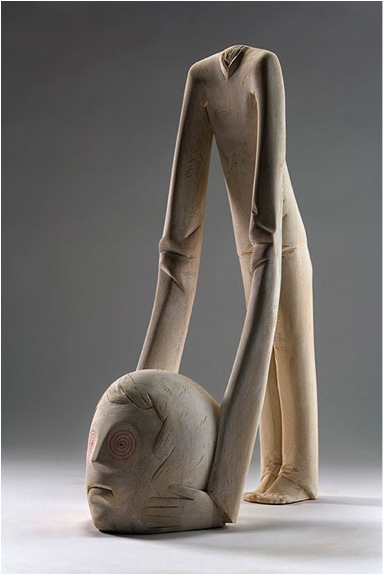

Sylvain Guenot

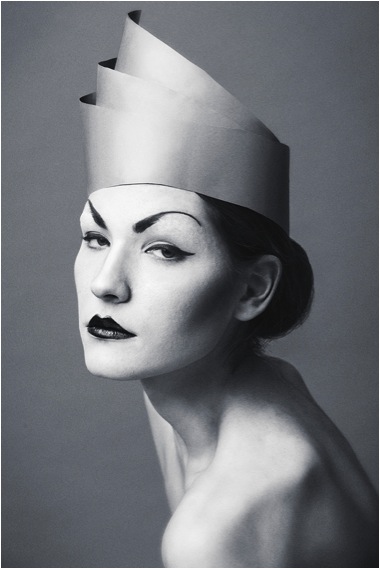

What are some important things that you need to go through with the sitter to get the best results?

I spend quite a lot of time with the sitter(s) before the actual start of the shoot. First I show them samples of my work to remind them the specific nature of my portraiture so that they "understand" what I expect of them. Then they show me round inside and outside the house so that I can spot the places with potential. Finally we choose together the clothes to be used to match best the various places. This is a very intimate time to build up the necessary confidence needed for a successful shoot: intimacy between photographer and sitter is a key thing in my experience.

Of course you also work in colour, can you discuss why colour is important for these prints?

In both these photos the link between sitter and surroundings is made by colour mainly, in these two cases black and white would have diminished the impact rather than enhance it. In quite a few of my colour photos the main feel remains monochromatic, sometimes there is somewhere in the picture a little splash of brighter colour

I actually mainly work in colour nowadays although I do think monochrome extends the artistic dimension of an image providing it is the right type of image. Some images have to be colour otherwise they become pointless.

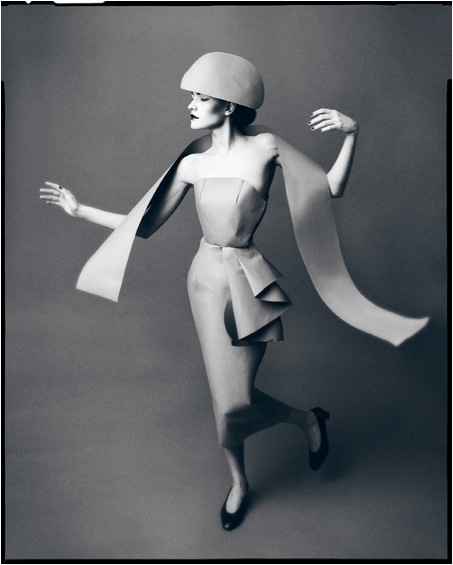

Composition is a very important part of you photography, can you expand on this aspect?

Yes, composition is essential in my images: there is actually a lot of geometrical shapes involved whether they are around the sitter or the sitter. My aim is to make them talk together in an harmonious way to produce a successful image. To do that, at the composition stage in my viewfinder, I consider the sitter (actually the space he/she occupies) as an abstract shape taking no more importance than everything else around background and foreground. I regard the whole thing as an abstraction of the reality which I then photograph. The image comes out of it where the sitter and the rest cannot be visually dissociated they are bits of the same working machine.

If you take out what is around the sitter, the portrait is poor, or alternatively if you take out the sitter, the image is incomplete and cannot live by itself. Interestingly enough, some people who see my work for the first time in an exhibition ask me if it is painting or a photograph?

Can you discuss the sitter’s reaction on seeing the final image?

Sometimes some of them who have not fully "understood" my approach might tend to only look at themselves not being able to take the whole thing in one go, so it can disturb them a little bit….

This is Sir John Houghton, he is a scientist who received a joint Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 for his team work with Al Gore about climate. This portrait was commissioned by a publisher for the front cover of his biography which is coming out in September 2013. The brief was to illustrate the "Conflict" our planet is facing through the voice and work of this highly respected scientist. Again use of foreground and background.

What do you mean by the word “peoplescapes”?

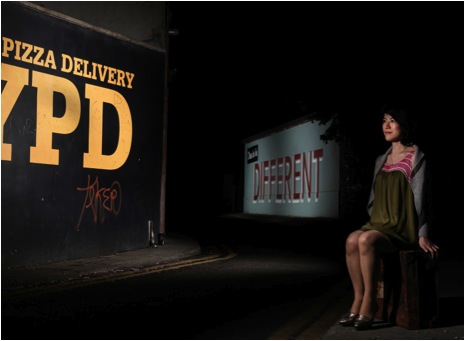

This is what I call "peoplescape" a word I feel I have invented but probably already existed before… I mean an image which contains a person or more than one but which goes beyond showing that person. It is an artistically pleasing image altogether which creates an emotion. Being supported by somebody' s presence in association with abstracted surroundings suggesting (often in a subliminal way) rather than informing in a 'documentary" way

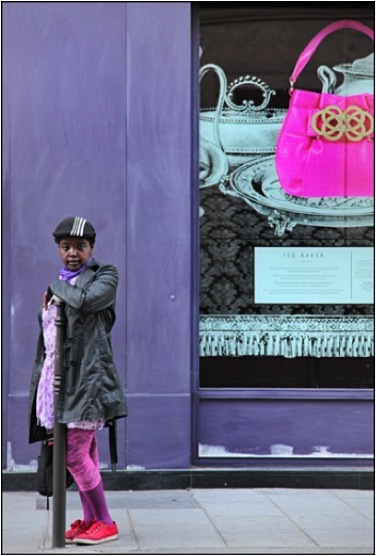

The abstracted background is used in a way to suggest Chinese calligraphy for this French Woman who is temporarily experiencing the life of an expat in Hong Kong

You see beyond the image and want to capture the character, can you expand on this?

Yes, the particular use of background/foreground I make, inevitably (and intentionally), reveals character in a subtle, non explicit way which makes the portrait more appealing and more interesting. I feel each image has a psychology and I try to use it to serve the sitter's character in the image.

Here the surroundings are made of a foreground on top right corner (lampshade) echoing shape wise with the yellow collar of the shirt but also merging with metal staircase and windows in the background to produce a kind of disturbing/distressing feel which serves character for this young Danish expat girl in Hong Kong.

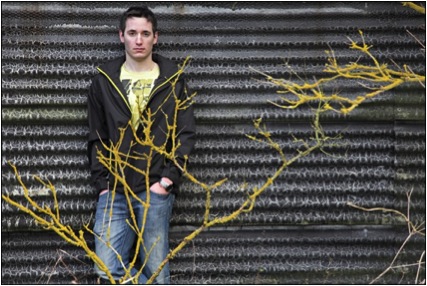

This man is an English high level cage fighter, I am aiming at showing his strength and also vulnerability, first layer of fragile green twigs acting as a foreground and second one as background, together suggesting subtlely the cage he fights in. Note how the shapes of the twigs replicate those of the shirt and therefore assemble sitter and surroundings in one working image.

You also use light in your work?

The combination of the strong side light with the settee designed cushions create an appropriate Dickens type of atmosphere to portray that little rascal.

Your major work is portraiture. You have also completed “The Hong Kong project” - can you discuss this project?

I took these photos on my numerous trips in Hong Kong between portrait commissions, I was fascinated by these derelict walls whose natural abstract patterns tend to evoke an infinity of concrete things depending on the way your mind decides to look at them. Interestingly enough the photographic process there was to transform abstract forms into more real looking ones as opposed to the "peoplescapes" which are about abstracting real things. Both processes complete each other and require the same artistic vision and abilities.

Do you have other projects that you are working on or have done?

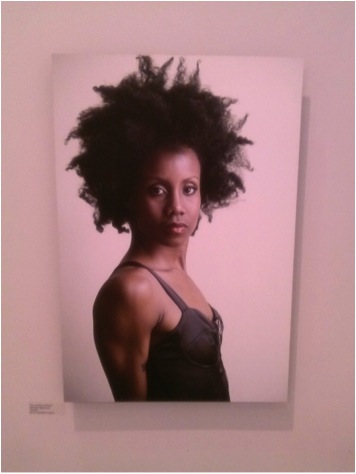

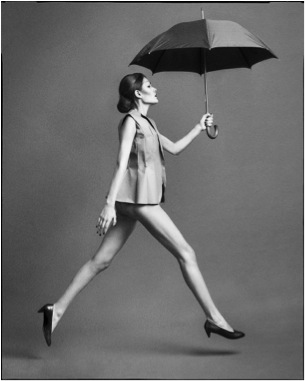

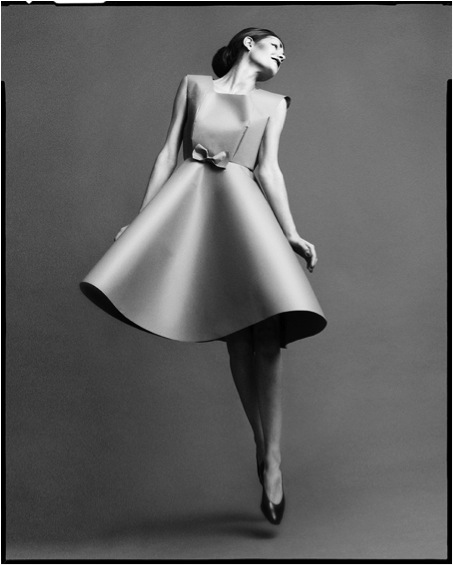

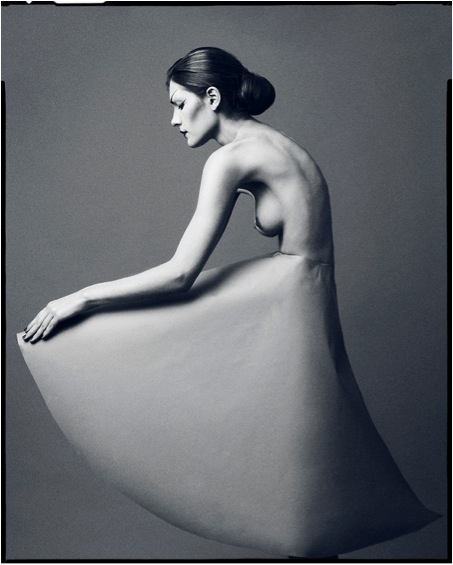

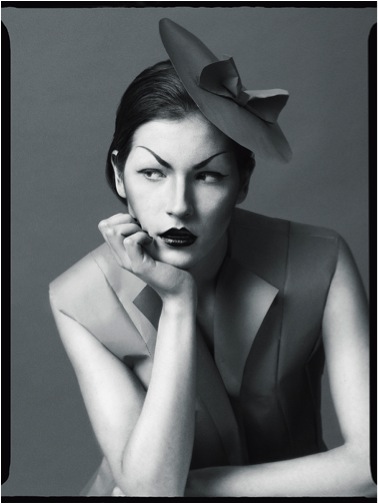

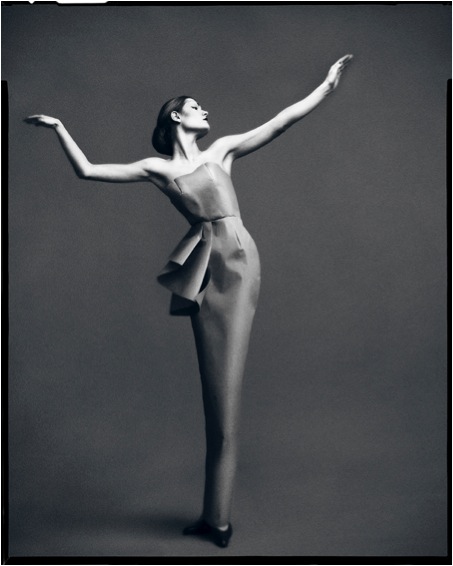

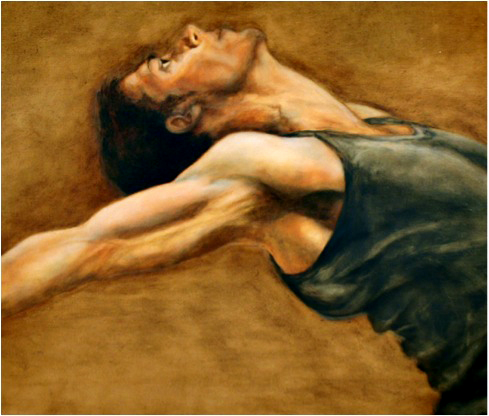

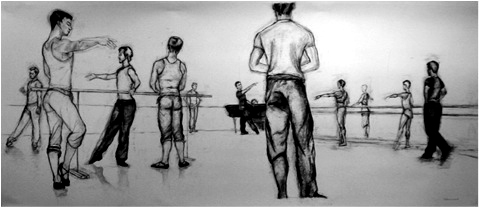

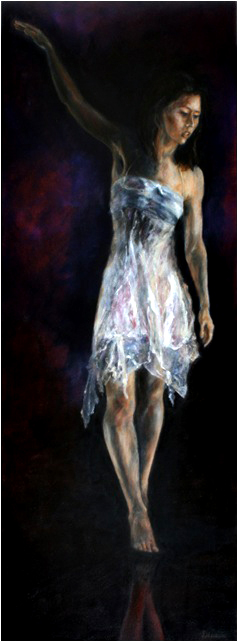

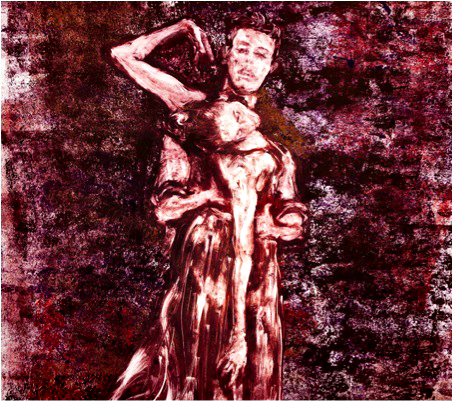

I currently have an exhibition of portraits of famous American Contemporary Dance dancers in New York and I love the idea of doing a similar thing with UK dancers at The National Portrait Gallery in London but I will have to convince NPG first….The NYC exhibition is called "inAction, The Virtuosity Of Presence", my challenge was to show the virtuosity of the dancer through a "portrait" where this dancer is not dressed as a dancer, not performing, not even in a dance environment.

Topaz Arts Inc 55-03 39th Avenue Woodside, NY 11377 for “inAction: the Virtuosity of Presence” new portraiture featuring 40+ New York-based dancers & choreographers photographed by Sylvain Guenot.

‘Carmen de Lavallade’

I am also in the middle of setting up a commercial project consisting in getting Asian people to come and have their wedding (or rather pre-wedding) photos taken in England and France. A coffee table book of portraits of famous people around the world is also in the pipeline, it is too early at this stage to reveal more about the project.

How has photography changed for you since digital and software such as Photoshop?

It has changed dramatically and for the better: first I was very reluctant to leave my film camera as I was convinced digital technology would never enable me to produce such good black and white, black and white being the only way for me…. Not only it did a very good job in that respect but it also gave me a chance to discover colour and find myself loving it to a point I nearly only produce colour work nowadays. I actually find it difficult to convert colour digital files into black and white when I previously photographed the scene with colour in mind. Also digital technology has enabled me to take more work on as it makes it possible to work much faster and more efficiently than in the darkroom. Finally I love the control on the image you get through Photoshop or any other software of that kind.

How large can you have you prints processed?

I always do my own printing because I want to keep control of the image until the final stage, interpreting my digital file in a similar way I used to with my negative in the darkroom. My Epson 3880 printer allows me to print up to A2 (60.5 cm x 43 cm). Much larger prints can very easily be achieved with my high resolution files (Canon 5D Camera)

Can you explain to the reader that as a professional you don’t expect to get that one image with one photograph and it isn’t simply a case of being a professional, you too need to take many to capture the perfect image? Discuss?

Absolutely right! First I need to find the idea which means the right place in the right light with the sitter wearing the right clothes. With the experience I have become good at working out quite quickly (sometimes a bit instinctively) which combination of these elements would have the potential for a successful image. Then it is a question of trying it and sometimes it can take many shots indeed to get the one(s) providing the expected pleasing result. I would advise to always work with an idea in mind, working randomly is rarely fruitful.

Contact details.

Website: www.portrait-photographer-gloucestershire.co.uk

Office: 0044 1453 764849

Mobile: 0044 777 98 19 602

Sylvain Guenot, Gloucestershire, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October, 2013

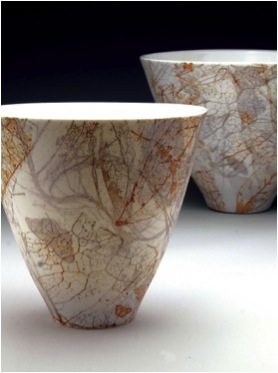

Regina Heinz

You have done many residencies in the UK and beyond. Can you expand on the importance of them to you work?

Residencies are a great opportunity to push the boundaries of one’s work. They provide time, space and usually good facilities and thus encourage to experiment, try a different scale or introduce a new technique.

All my residencies have worked in this way. Two of them were particularly beneficial: At the beginning of my career I spent three months at Cleveland Crafts Centre, Middlesbrough, England and in 2011 I was invited as part of the British contingent to create work for the Fule International Ceramic Museum in Fuping, China.

‘Dress’ Brushed Lithium Glaze, Middlesbrough

‘Middlesbrough’’

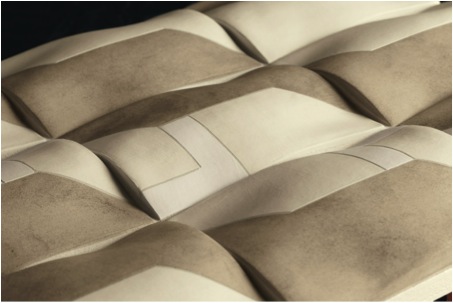

Middlesbrough is an industrial town in the North East of England not far from the lovely rolling landscape of the Yorkshire Moors. I was startled by the stark contrast created by industrial plants eating into the natural environment. This prompted me to “cut” into my organic pillow shapes and to introduce “manmade” right angled elements in order to visualise this contrast.

Since then I have cultivated this contrast. Balance and juxtaposition of precise geometric components and softly undulating sensual forms is one of the main characteristics of my visual language.

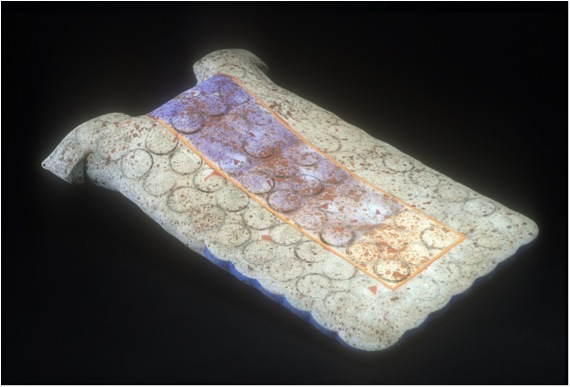

The residency in Fuping took place in a brick factory and not only provided a huge working space but also the opportunity to work with prefabricated elements.

‘Fuping Residency’ – New Roof

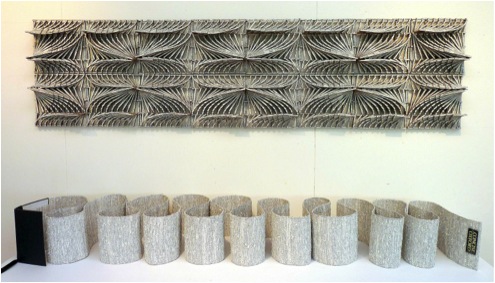

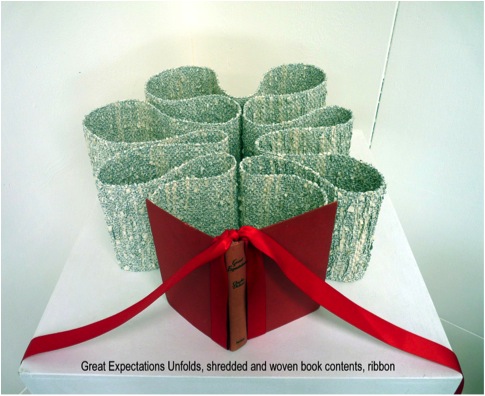

The factory produced curved roof tiles amongst other products. I used 70 of them to create the large relief sculpture “A New Roof”, displayed on the floor of the British pavilion. This sparked off ideas of creating my recent body of large scale wall based work, 3D undulating wall units, cast in Stoke on Trent, hand painted in my South London studio, which can be combined in different ways to create installations for interior and exterior settings.

New Roof- detail

Are there any special tricks to winning residencies that you are willing to share?

It is always good to indicate why you are applying how and in what way the residency will benefit your work. Usually residencies have certain criteria when looking for in suitable candidates. If you want to apply find out as much as possible about the residency and in your application try to fit the criteria.

Exhibiting of you ceramics: how, where and why?

Exhibiting and selling my work is a form of communicating and thus vital for my professional life. I am grateful to have been able to exhibit in many different venues all over the world, including galleries, competitions, museums exhibitions and ceramic and interior design fairs. All these venues demand different types of work and target a different audience, one off pieces and special pieces are best exhibited in galleries and museums, my recent wall based work also fits the criteria of architectural ceramics and has been successfully exhibited in interior design fairs over the past years.

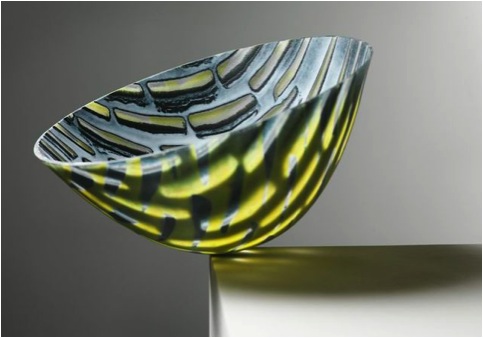

Architectural Ceramics ‘Collection Flow’

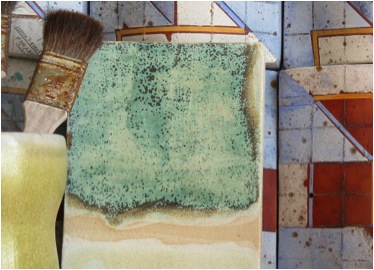

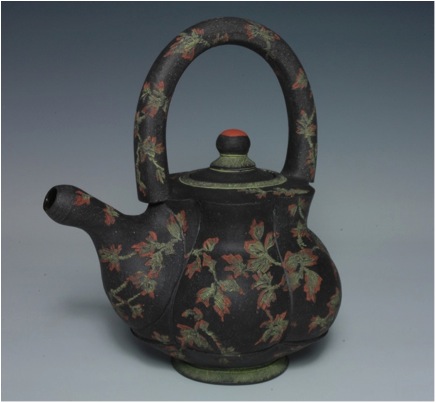

Your initial training was in painting. Can you explain how this can be seen in your current work?

All my work is essentially painting onto a 3-D surface. I love colour in general and the richness depth and texture of ceramic colour in particular. I also love the act of brushing and when decorating I am building up layers of colours and textures.

Oxides, glazes, biscuit slips, washes of ceramic pigment and most recently ceramic transfers and gold enamels are applied in sequence and juxtaposed and very often fired on in between in multiple firings, thus creating depths and vibrancy which adds to the richness and sensuality of the organic form. Bits of the layer underneath are very often left exposed thus emphasising the act of painting.

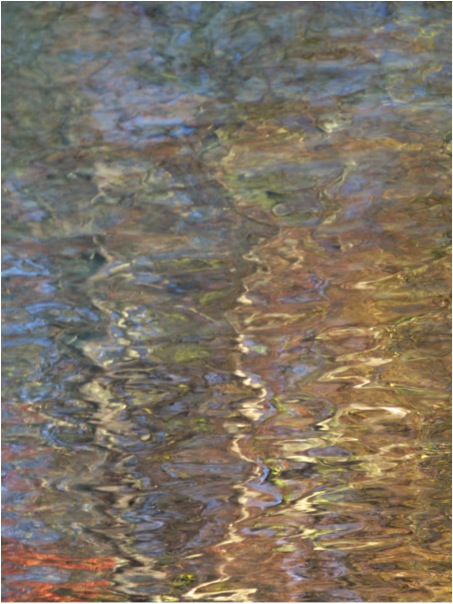

Most recently in my high firing range I have discovered shades of colour and natural phenomena like a sunlit moving water surface are translated into a ”carpet” of different coloured tones, golden highlights and bold patterns.

‘Flow Collection ’ Brushed Stoneware Glaze

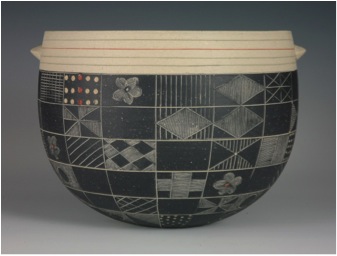

We see a lot of rhythm and repetitive pattern work, please discuss?

As with my colour palette also my patterns have been derived from nature and observation of natural phenomena.

The movement of water is one of my main sources of inspiration and is translated into undulating forms and wavy repetitive patterns and designs.

Over the years my focus on the landscape has undergone an interesting change. Overall views have been submitted to a process of “zooming in” and “blowing up” of smaller and smaller areas. Close ups of surfaces, details of natural and manmade environments now serve as starting points.

‘Cityscape’ each tile 20x15x3cms

Your work is hand built. Can you expand on your technique?

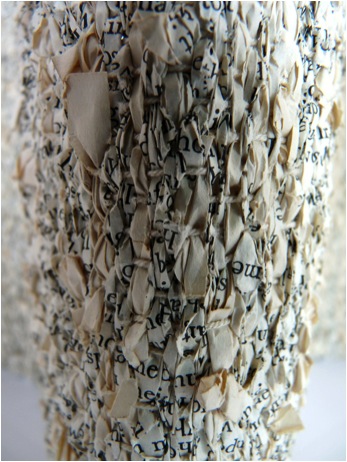

All my hand built work is constructed from soft slabs in order to emphasise the sensual and tactile qualities of clay.

The process can be compared to “tailoring”, the designs are developed on a flat surface, then slabs are rolled out, cut and incised similar to pattern cutting. The slabs are shaped while still soft by gentle pressure applied from above or underneath to create an undulating surface. I always try to manipulate the slabs as little as possible and to retain their original surface texture, cracks, markings, newspaper creases etc. to the highest possible degree. This technique is paramount to my work and requires both spontaneity and control. The soft slabs react immediately to every touch, every movement of the hand and are easily over-worked, in danger of losing their elasticity and freshness.

When leather hard the slabs are joined to form a 3D object. This is the most exciting stage in the making process and results in a piece which unifies colour, form, texture and design.

I use grogged Stoneware clays for technical and aesthetic reasons. Grog provides tactile and visual texture as well as strength for better control during the forming process.

‘Cityscape Collection’

Can you explain about both your studio and the importance of an arts grant to help you set it up?

Maintaining a professional studio is an essential part of working as a ceramic artist.

I received a setting up grant from the British Crafts Council when I started out. The help was invaluable, I was able to equip my studio with a proper kiln, pug mill and slab roller and turn it into a functioning ceramic studio. The grant also kick started my career as my work was included in the promotional campaign run by the Crafts Council for all the grants recipients.

Your work is suitable for internal and external display. Can you explain how these differ?

I have two firing and glaze ranges.

The decoration of my low firing indoor range consists of a Lithium glaze fired to 1035°C and various oxides, washes of ceramic pigments and biscuit slips.

The final effect is the result of multiple firings; layers of colour are fired-on between applications.

The high firing range uses a stoneware glaze with a high China clay content that generates a beautiful mat fresco like surface, well suited to “clothe” the organic undulating forms. Oxides and stains are added in varying quantities to achieve shades of colour. My high firing colour palette comprises warm tones, browns and ochre as well as blues, greens and greys.

How are your wall sculptures physically hung?

The wall sculptures are mounted on boards, either glued for a permanent fixture or screwed on using cavity screws for a non-permanent installation.

If required the modules can also be glued permanently to the wall using a tile adhesive.

‘Flow’ 300 x 140 x 5 cm

Colour and pattern is intrinsically part of your work. Please expand on this?

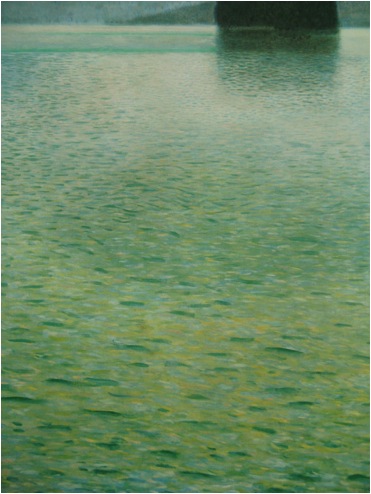

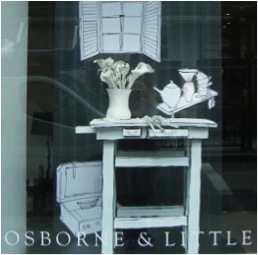

The Austrian painter Gustav Klimt is very well known for his highly decorative and ornamented art nouveau portrait paintings of high society ladies in Vienna around 1900.

Perhaps less well known are his beautiful landscape paintings he created during several summers when he stayed on the lake “Atter” (Attersee) in “Salzkammergut”, Upper Austria, the same lake where I used to stay during my child hood summers.

Lake Attersee, Upper Austria

I particularly love the paintings which depict the lake. Though observed from nature the different shades of blue and turquoise of the water surface are represented by single brush strokes in different colours, which when looked at in isolation, remind me of abstract paintings. The visual impression of glittering light, reflection and movement has been translated into tessellations of colour, very similar to the process I am using in my work: Observation from nature are simplified, abstracted and distilled into colour, patterns and forms.

Water Surface Island Donthe, Lake Attersee

Water surface – inspiration for ‘Flow’

What are the sizes of your work?

I love to work in groups or to themes, large scale, and for particular sites Therefore depending on the circumstances or commissions there are no size restrictions. My sculptures start from usually 30 cm, my largest free standing sculpture so far was 160 cm high, restricted only by the size of the available kiln.

‘With a Twist’ 63x55x30 cms

The modular nature of my wall based work lends itself to large scale and can easily be extended to whole interior or exterior walls. The largest piece so far was 2 x 2 m and was created for an exhibition display for the American company Ann Sacks.

You comment that you get inspiration from the mountainous landscape of your homeland, Austria, how?

My work is biographical and topographical and draws from my early memories of growing up in a particular beautiful mountainous part of Austria. Rather than telling stories and incorporating a narrative I am conveying my feelings and visual impressions in a more abstract way and encourage the spectator to create their own stories and memories. Very often I use the camera as a vehicle to explore my surroundings. Photography is part of my creative process, with the image abstracted, tessellated and integrated into softly undulating ceramic forms. Like photographs my pieces are impressions, “3-D snapshots” that capture moments in time.

‘Engaged’

You have your work in many UK and international galleries. Can you explain how you have been able to develop this network and also how you keep up with the work load?

I am a member of several professional associations including the British Crafts Council, the British Craft Potters Association and the International Academy of Ceramics. This helps with networking, getting to know key figures in the ceramics world and obtaining important information regarding galleries, exhibition opportunities, competitions etc. I have also always proactively researched and applied to suitable galleries, presented my work at fairs and most recently started a newsletter sent to my contacts on a regular basis. In general I try to “communicate” my work through exhibitions, publications, competitions and taking part in workshops and symposia. In 2011 I demonstrated at the International Ceramic Festival in Aberystwyth, which also has greatly extended my network.

As to the work load it is important to be organised, to plan ahead and to prioritise the most important events. Occasionally I also employed an assistant and had help in the studio from students and interns.

‘Keeping Time’

You have had to develop a way of packing and freighting you work around the world. This would often be a problem that stops other new ceramic artists, can you share some of the secrets?

Shipping is not really a problem. There are now very good online shipping companies available who offer competitive rates all over the world.

The real secret is packing. I had very few breakages over the years. One has to allow for plenty of space around the piece filled with protective fillers like polystyrene. Using double boxes is also very good and in general packed like that the piece will arrive safely and sound.

‘Flow’

Your work is in many collections, can you take one or two that have given you particular delight and why?

It gives me great pleasure to know that my work can be found all over the world. Two collections stand out:

One is the private collection in California. Paul F. Dauer is an enthusiastic and knowledgeable collector of British studio ceramics, and I am very proud to be part of this fine collection.

The second one is Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, Gifu, Japan. Two of my ceramic sculptures were added to the collection this year. Created in 2000 the museum focuses on modern ceramic art and aims to represent both functional and non-functional international ceramic art in a beautiful setting, making it to one of the finest ceramic art museum worldwide.

What are you currently working on?

My most exciting project at the moment is designing panels to be included in the art work for a large cruise ship. Apart from developing new designs, patterns and shapes the project also involves working with the architect, managing suppliers and being involved in the whole process right from start, all of which is an exciting new departure.

‘Flow’ detail

Contact Details

Regina Heinz, London, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October, 2013

John Short

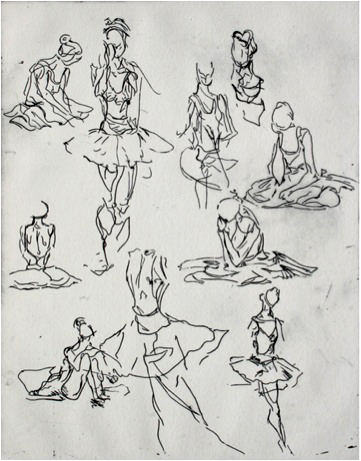

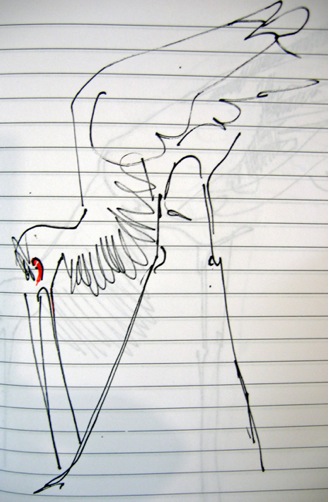

Sketchbooks are an intricate part of your artwork, can you expand on this?

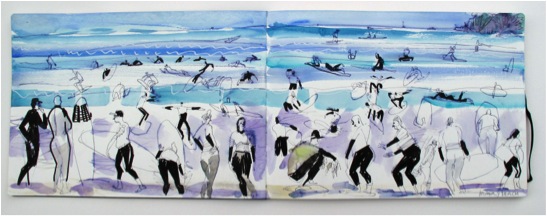

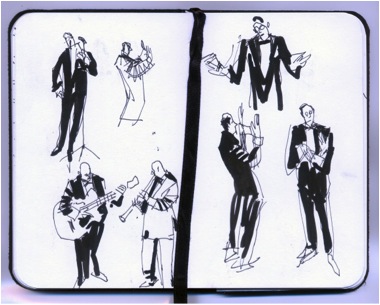

All through my college years and to date I have used sketchbooks for a variety of functions, the most important one is familiarising myself with the drawing, shapes, foibles and movements of my subjects be they people, birds or animals. I also use them to experiment with arrangements and compositions. In these pages I can experiment with colour and collage. I have always believed that the act of drawing and visualising something means that, however slight, that my idea has become crystallised on paper. That’s really important and I never edit them as the drawings which don’t work out are often the ones that you learn most from. I work with a variety of sizes, shapes and paper surfaces of sketchbooks. They are not regular visual diaries, nor are they meant to be, but places where I record subjects as they unselfconsciously appear in life. At this stage I have many, many volumes and often comb through them for useful fragments in finished paintings back in my studio. I often think of finished paintings as large immediate sketchbook pages.

‘Manly Beach’

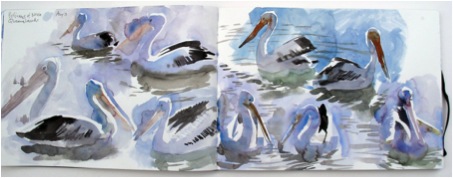

‘Birds'

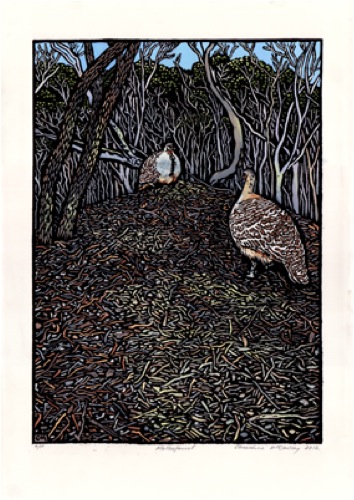

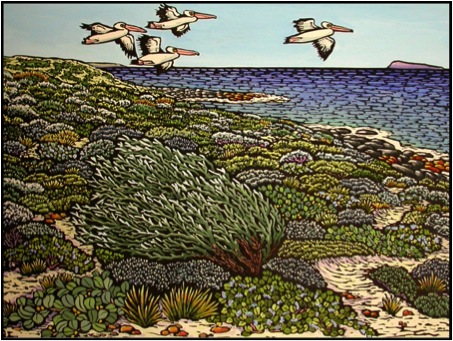

I also followed a lot of the truly exotic bird life around; a highlight was a flock of pelicans at Noosa in Queensland.

‘Pelicans at Noosa'

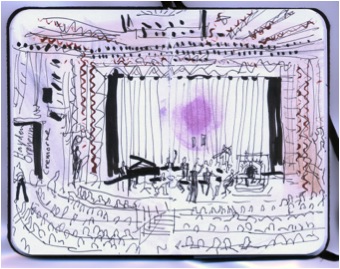

Also a series of drawings done during a musical concert in the Hayden Orpheum in Cremorne, a beautifully restored Art Deco movie theatre.

The plan is to return to Australia next July/August to explore and do more now having taken in a lot of potential locations. I bought a beautiful gigantic A3 moleskin watercolour sketchbook in Shanghai which I used specifically for my Australian travels. I also filled a couple of pocket sized sketchbooks.

You have sketchbooks, but what other documentation do you do of your work?

My work methods are fairly simple I will draw my living moving subjects in sketchbooks and use my digital camera for use in recording background locations. Recently I have been working on combining photo transfers (digital images) and ink and watercolour drawings. This has been very interesting technically and I make a lot of use of my camera and colour printer. I have to also keep my website up to date with scanned 2D and photographed 3D works.

'Bloomsday, Ukelele Band'

When you do your initial sketches composition is high on your agenda. Can you elaborate on how you get such variation of composition?

When I was a student in the Royal College of Art in London I set Sundays aside for visiting galleries and studying composition and colour in paintings. I have always been a big fan of Degas, Hockney, Bruegel, Singer Sergeant, Utamaro and Sydney Nolan to name a few. It helps to study how others construct effective compositions as well as developing and formulating your own.

How do you manage you work load between teaching, travelling, sketching and time in your studio?

I think the answer to that is to combine a lot of these things. My teaching involves a fair bit of travel and I work in cooperation with a colleague, Tom Kelly, who is a highly experienced photographer. We work together teaching image making (includes drawing, illustration, photography) with visual communication students in Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT) and this has involved a lot of location work, regularly in Morocco and China.

Our teaching method includes us producing work on location with the students and followed by a public exhibition of the results of their work and ours. One of the highlights of this practice was a six week location project with our students and students of Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts documenting the gigantic EXPO world fair in China. Otherwise I work in my studio whenever and as much as I can. I’m lucky as I work relatively fast after a lot of preparation and visual research.

'Cormorants, China'

Place is very important to your work, you get great inspiration while away. Can you discuss how you combine travel and teaching?

As with the recent trip to Australia for me travelling is always inspiring and it’s not difficult to be inspired and inspire students when on locations abroad. It’s easy to forget how influential these field trips can be for students who often use the wealth of visual research material they collect towards other project work on their return. It must be said that for me it’s very interesting seeing what inspires the students on site also. I’m proud to say that the work we do with the students has been described as a showcase for our School of Art and Design in DIT.

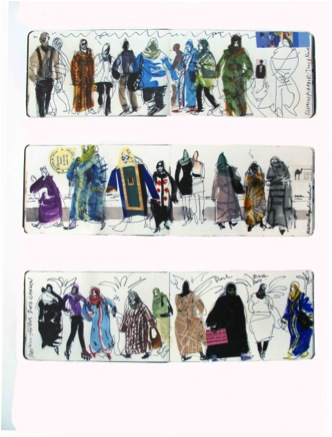

‘Moroccan Sketchbook’

Water is in many of your paintings, can you comment on the mirror effect of painting water?

Reflections and wave patterns are lovely things which are fairly difficult to handle. Water changes so much and the effect of reflected light, colour and shadow can be managed if you can control ink and watercolour allowing them to flow and do what they naturally want to do, what I mean is that they are perhaps the most appropriate and subtle media for this subject. Again it helps if you look at how other artists handle water reflections; the American artist John Singer Sergeant for instance did a series of beautiful watery watercolours of boats in Venice. In watercolour, unlike oil painting, it’s easy to see how it is done. It’s incredibly difficult to do it of course but the trick is to make it look effortless.

‘Scotland #3’

‘West Ireland Sketchbook’

Earlier you had commissions from both newspapers and magazines. How has this work developed the work you do today?

I worked for several years as a freelance illustrator for newspapers and publishers in London and in Dublin and I enjoyed the challenge of each job as they came in. I had no idea what might be asked for subject wise from portraits to editorial, to court room drawings, to food illustrations, to book jackets and posters. It was all very demanding but I certainly learned a lot and was able to successfully work from photo libraries and on site to create material for reproduction. I haven’t done any commissioned illustration for many years now but I still enjoy doing family watercolour portraits as commissions. I certainly could write another article about that whole area.

You are the Senior Lecture in Drawing and Image making at the School of Art & Design, at the Dublin Institute of Technology. Can you share one or two pieces of advice that you give your students?

It is all about basics and the basics are the same for Drawing, Illustration, Image making and Photography. It goes without saying that being professional is essential and remembers that the world is endlessly hungry for new and original images and ideas. Make sure that you understand what is required in a brief and anything of yours that your mother likes – tear it up!

Many of your paintings are made into prints can you discuss the decisions that must be made in this process?

A selected and limited amount of my paintings have been successfully reproduced as digital prints, or giclee prints as the process is technically known. It’s a highly faithful reproduction of original artwork which is something that you either like or don’t like however there is no denying the beautiful quality of the printed image. Opinion is clearly divided and some gallery owners and collectors can be very sniffy about them but for me a limited edition print can be much more affordable alternative for a lot of people. The decision to print an edition is something I always discuss with the owner of the original. It is true to say that most sales via the website are prints. To distinguish the original from the print I make a point of reproducing it to a slightly smaller size than the original. They are expensive to produce and you need therefore to consider the edition sizes as well as price. With this kind of printing the print companies charge often by the square centimetre and a once off charge for photographing or scanning.

You do wonderful work capturing the everyday, can you discuss this?

Observing how people move and interact, their body language, their costumes, their shapes and all their imperfections are intensely human and it’s this I find endlessly fascinating and entertaining. In unselfconscious moments people can be very revealing and honest.

In different locations and cultures the everyday becomes exotic, please discuss?

For me it is like theatre with lives being acted out in similar ways but in different costumes and locations. People do interact and behave in different social ways and have exotic cultures but underneath they are all still people who have their own individual foibles which are unique. Those are the pearls which you have to look for no matter whether you are here looking at bathers in Ireland or Australia, dancers in China or shoppers in Morocco.

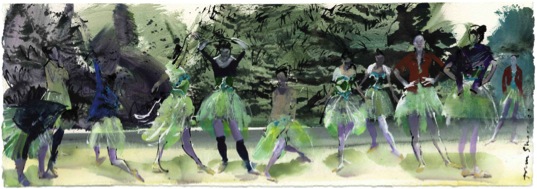

‘Ballet Class in the Park, Shanghai, China’

Discuss the use of current technology in your art?

I am always looking for new ways to change and develop my work, particularly with the technologies available that are developing at a dynamic pace. It’s all highly seductive of course but what you need to understand is that it all has to work for you and your demands. I use digital photography via software and my printer to achieve what I want to do. Right now its photo transfer and combining media in images but I would love to have time to animate drawings, perhaps that is the next thing? I have done some work in 3D drawings and I would like to experiment with some 3D sculptures on a 3D copier.

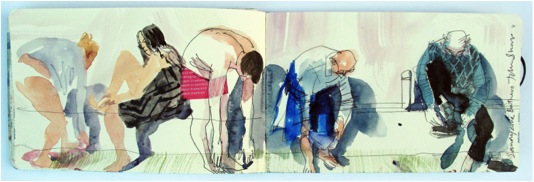

Can we look at Forty Foot: please explain the name?

Nearby to where we live is a public outdoor bathing place where people swim all year round, summer and winter, I guess for all sorts of reasons, mainly health and life affirming but it’s a real local tradition and has quite understandably become something of a tourist attraction. It’s a natural deep rock pool in Dublin bay which, it is said was named after the Highland regiment 40th of foot who were stationed there in a Napoleonic fort in the 19th century, but its origins are fairly obscure.

Inspiration?

For a charity fund raising event some years ago I was asked to contribute a few paintings that I put together from sketches I had made of bathers at the Forty Foot. They proved to be very popular and I began to supply prints and more paintings to a local gallery and the combination of my quirky drawings and quirky subjects really struck a cord.

‘Winther Bathers - New Year’

Location?

The specifics of location are really important to my work. They are all places which are accessible and I think that their charm is that aspect and my visions of those places, that’s why I think that the fusion of media with photographic elements and drawing works and is worth developing. After all photographs have a function and drawings have a function in imagery.

‘Bewleys Café, Dublin, Ireland’

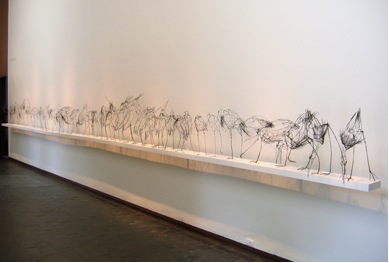

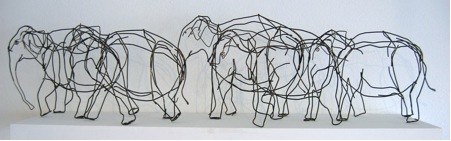

You have also made 3D images can you explain about this work and in particular related to Forty Feet?

I have made a few series of 3D figurative sculptures from packaging card inspired by the simplicity of Picassos’ simple folded card figures. I worked on a series of local bathers and also a series of couples practising ballroom dance moves from a park in Shanghai. This was a new and enjoyable departure from 2D to 3D and as a French friend of mine said, that it must be very interesting for me to walk around my drawings. Working with cheap materials really appealed also, it makes them somehow more honest and to use that word ‘quirky’ again. There is certainly a lot more development work needed on those but so far so good.

Your aim is for your work to look spontaneous and unplanned but this is not really the case. Please expand on this?

Some time ago I ditched the ubiquitous bouncy castle at one of our son’s birthday parties in favour of having the kids all sit individually for small watercolour portraits, which they all got to take home with them in their goody bags. It really was great fun, it’s a bit of a real party trick actually and at one point as I was painting one of my sitters, I was conscious of a boy watching over my shoulder and nearing completion he called the others through to look and said ‘Wow! It starts of crap and then it’s cool’

Actually sounds like a metaphor for my career.

Otherwise…

Giving the impression of spontaneity is important in my work. Being casual and relaxed certainly helps through much practice and draughtsmanship. Often the quickest seemingly throwaway and most immediate use of materials can often capture more than a few too many strokes. Make it look effortless, controlled and well observed.

‘Pelicans, Noosa, Australian Sketchbook’

Contact details:

Email: John@johnshort.ie

Website: www.johnshort.ie

John Short, Dublin, Ireland

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, August 2013

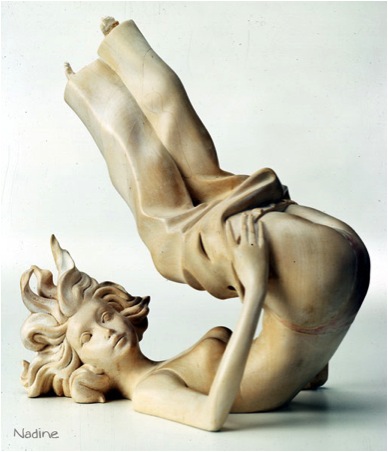

Kathy Venter

You use very traditional techniques of hand coiling and pinching in you work, can you elaborate on your technique?

I began hand building by using the coil method. The application of a thick coil of clay around the circumference of the upper edge of the form and then pinching this coil to blend into the clay form below and upwards to extend and resemble the wall below. To follow the outer line of the form more accurately, I later used smaller lozenges of clay pinched into place. I’ve adapted this method to suit the specific challenges of creating figurative life-size work. Unlike many of my contemporaries, I don’t make use of any life casts, moulds into or over, or modelling over an armature. I finish the shaping of the area I built the day before by bending and paddling the wall – then add a new area of rough form above this and repeat the process.

The model poses for me throughout.

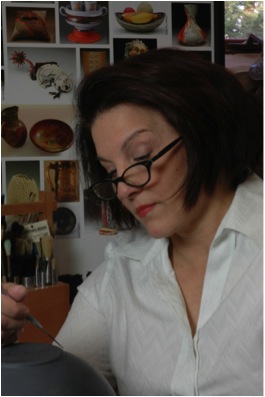

Kathy in her studio

Currently you have a huge installation at the Gardiner Museum. Could you tell us about your relationship with the museum? How ‘Life’ came about? The time line you had to prepare for this whole exhibition?

The Gardiner Museum is the largest museum of its kind in Canada and attracts visitors from all over.

The head curator – Dr. Charles Mason visited my studio having an idea in mind for a large scale exhibition which would be a strong and full use of the new space for contemporary ceramics being built onto the Gardiner at that time.

When he saw my work in person he felt this was an answer to the headache of whether a vessel form could ever be referred to as sculpture. The popular theory defined a vessel as any ceramic form enclosing a space – and sculpture not. The popular definition of the vessel as craft is seriously challenged in my art as the hollow clay form created in the making of these sculptures had no practical function and the outside form is obviously sculpture, i.e., fine art. But the technique of pottery making is the fundamental process in creating these works. I have a respect for the basic fundamentals of craft existing in the sculpture of all societies. The argument of art versus craft has traditionally had very little relevance in most societies and I believe that this argument has run its course in the contemporary debate. We have to remember that the work “art” comes from the Greek “ars”, which means craft. So during a period of high art, the best craftsmen were valued. In fact, my sculpture, because of the medium, consistently straddles what could be considered craft and what could be considered fine art. My work has only been exhibited in contemporary fine art galleries.

I had three years to prepare for the show, but this extended into six years because of other commitments for the Gardiner.

As well as the exhibition, there is a beautiful catalogue: can you discuss how this catalogue came about and your involvement in its production?

I had good documentation of all my work and Deon, my artist husband, put the catalogue together with the images relating to the text. The biography was compiled using images of our early life in South Africa as well as our immigration to Canada in 1989 and subsequent exhibitions.

Can you discuss the importance of humanity and community to your work?

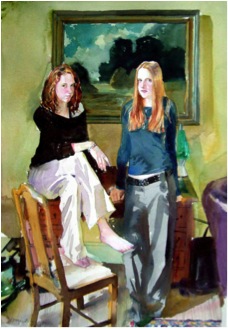

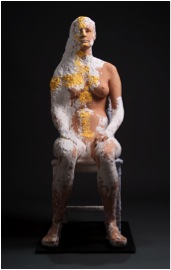

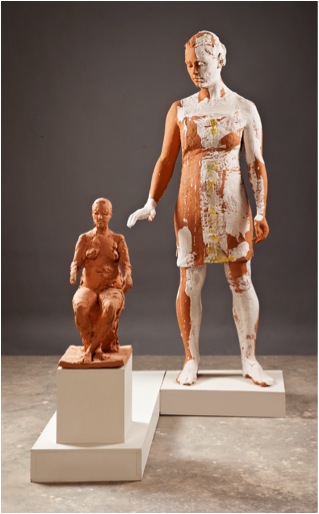

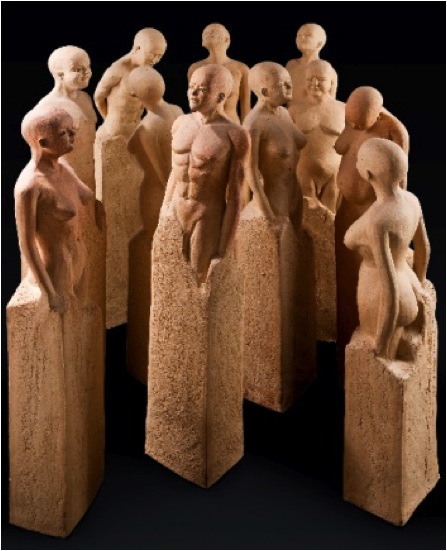

'Coup d’oeil #5'

In the installation Coup d’Oeil the subject of our collective humanity and community is most evident. These young women are all friends and have been part of this community for most of their lives. Looking at them grouped in the sculpture they could have lived ten thousand years ago or they could be from our times. My intention is for these figures to have the appearance of life itself, in its own process of coming to be. They’re universal. I take the approach of depicting the living persona, without generalization or objectification. Artists have the freedom to also show the enduring qualities in humanity, the strength within society as well as reveal our spiritual capacity. In this way the themes of our humanity are the visions of our poetic intuition and define our emotions. The human body is a universal for all cultures. Our past is linked to our present and all cultures through our humanity.

Ceramics and Sculpture are both part of your art practice, can you elaborate?

During my years at art school sculpture was my major and ceramics one of my subjects. I loved both and discovering an affinity with clay, I joined them together.

Your work is life size how do you get this to work taking into account shrinkage and breakage during firing?

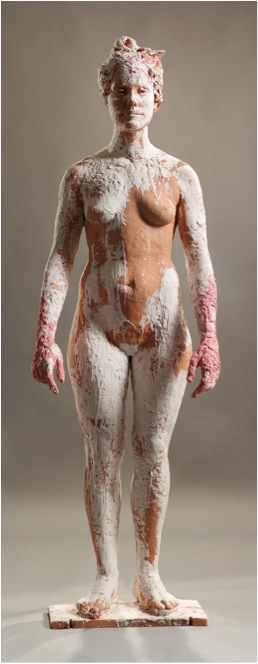

'Even Telling'

I build the figure approximately 15% larger than life size to allow for the shrinkage during drying and firing.

The Salt Spring women: can you discuss your relationship with these women?

Also your relationship with the tribal children in the Ciskei region ? Inspiration, location and artistic issues?

Using models of young women, from my community in the transition stage between child and womanhood, I could draw inspiration from my visual knowledge of the same stage of development in the tribal, Xhosa society in my area of the Eastern Cape in South Africa. There is a duality in the human form at this stage, sometimes both child and adult are evident, then again, only one or the other. In the Hogsback near our hometown of Alice in the Republic of the Ciskei I encountered children who made tiny figures of kudu and wild boar. Their sculptures were an immediate response to the primary experience of life there, with no exterior or learned referencing. About seventeen children supported their village by making these small clay images of animals. Walter Batiss, a local professor of art and painter, gifted some of these to Picasso who admired and collected them. Even if these sculptures were made on site with no knowledge of what art is, or potentially can be, these sculptures are high art and ultimately spontaneous. These children are creating forms in response to their own cultural matrix and yet they can be understood by all cultures. These sculptures are an unselfconscious response to life, part of a live culture. For these children mystical realism and mythology is not separate from daily life. There is no dividing line.

'Present Elements'

'Here and Here'

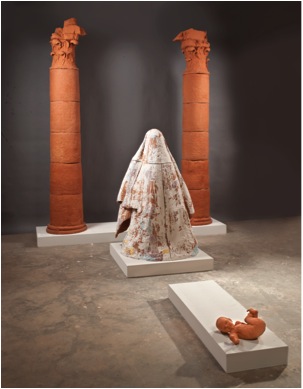

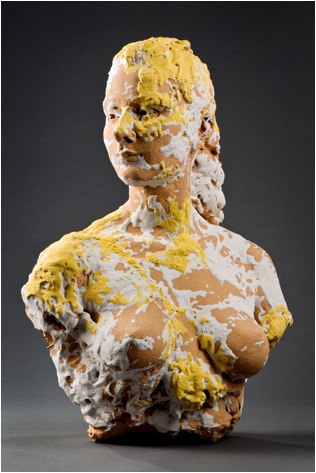

The use of the veil – how does this relate to reveal and conceal?

Metanarrative is a story within a story – I use it as a personal idiom suspended on the grid of an ancient tale or legend. In this work I use myth as the symbol of existence, of life itself and its essential meaning beyond the contingent occurrence of events.

The veiled woman is in stasis, the powerful emblems of national strength crumbling around her, unable to interpret the metaphor of rebirth and promise lying at her feet in the form of the infant child. The baby represents the woman’s progeny, our progeny, and is an embodiment of the future.

‘Metanarrative’

In complete contrast with the rest, this form is small, fragile, organic, moving, reaching outward. As a reconstruction of an idea of civilization Metanarrative suggests we conceive of cultural or historical values as constructs just as this scene is a construct that merges human figures with architectonic elements. More important, as personified by the child, is the living heritage we pass on, and a living culture, no matter how fragile or young. Any cultural dialogue, this sculptural installation Metanarrative implies, is a living dialogue with eternity.

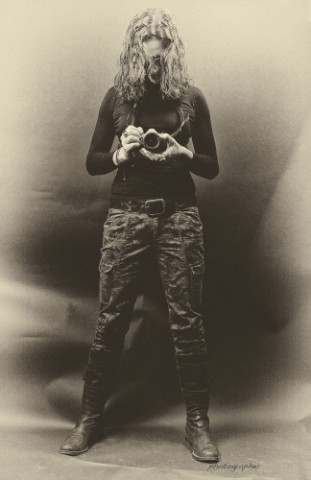

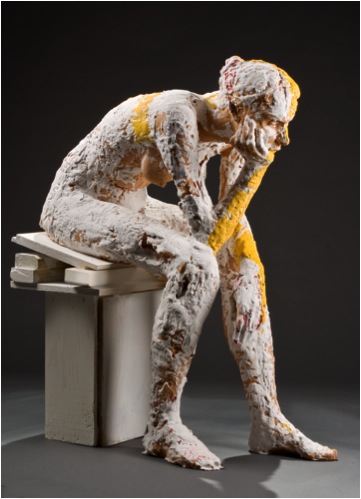

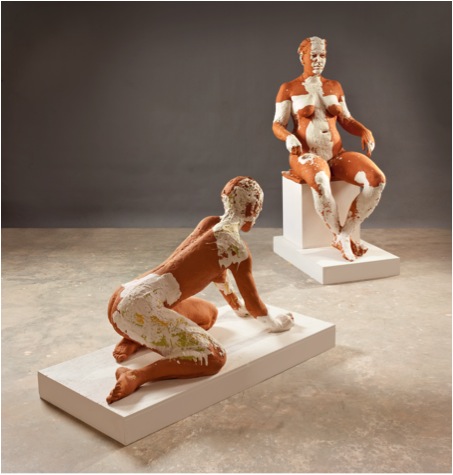

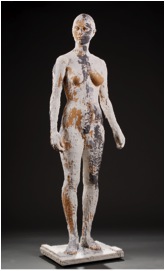

Can you discuss ‘Woman Drawing’ and how this evolved?

This sculpture builds a narrative using the physical communication between two figures. It is a metaphor for the process of making art – the reality of experience. The woman drawing is on her knees in front of the subject – the position describes the subjective attitude – an essential part of making an image of the live model – a reverence for the magnificence, complexity and diversity of the human form. Within this, there is no space for preconceived ideas or visual clichés on the part of the drawer – there is only receptive, careful observation and a delight in the resulting discoveries. In face of this – both figures are nude, exposed, one physically and the other intellectually. The dynamic tension, implicit in the way these two women interact, is defined by the self-assured confidence and passivity of the observed and the tight, energetic form of the observer.

‘Woman Drawing’

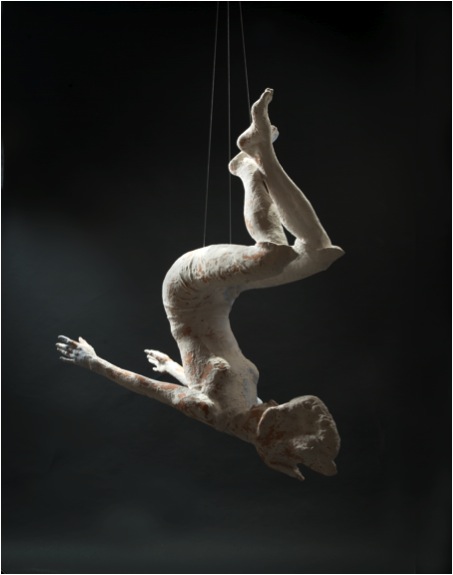

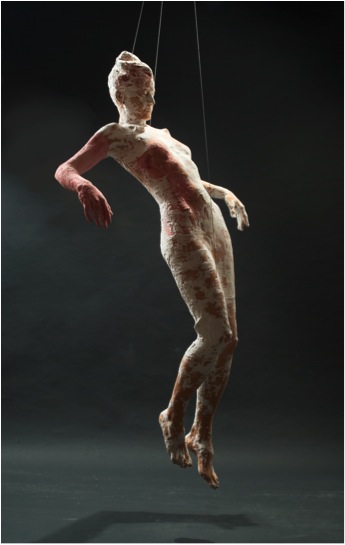

The immersion Series presents figures floating in suspended space. Discuss the inspiration for this series?

‘Immersion #15’

These sculptures are made from studies of my models underwater. Water refers to another dimension, an altered state of consciousness.

Figures in water react differently to sound, light, gravity, and movement. The human experience under water is cocoon-like – as if transformed back to the womb and in a private world of its own. The effect of gravity on the figure is diminished; there is free movement of the limbs and evidence of pressure from the surrounding water on clothing, hair and face

‘Immersion #17’

Suspended by cables in space the sculptures can be viewed from all angles – including underneath – freeing the work from the traditional pedestal, form, mass and weight of grounded sculpture.

‘Immersion #14’

Your art is influenced by many ancient works discuss the importance for you to look back to be able to move forward?

Whether in installation, performance, or sculpture, or any one of the many forms conceptual art takes, many artists today, including myself, believe that our rich visual heritage is a good source for reintroducing and advancing the language of art. From the dawn of time there has been the narrative: by the Shaman, by the Egyptian artists, the Chinese and European artists to tell their stories and to engage fully in the religious and spiritual world. I am adherent to the philosophy that the well-made object, by the artist, has an intrinsic value and is the preferred method for extending the language of art. In the process of making the sculpture – new things are discovered. This growth and transference cannot be accomplished by an intermediary. We often, now, search for inspiration in obscure influences rather than re-evaluating the accomplished examples achieved in the great periods of classical Rome, Egypt, Greece, the European Renaissance, and the Sung Dynasty in China. I understand that the past and present are always in flux. There are two ways of reconstructing the past – that of intuitively and mythically aims to define our emotions and experiences in view of the eternal concepts in ancient art. I walk a fine line between tradition and contemporaneity, I don’t re-create forms from the past, instead I reinvent and rephrase them using models from my own community on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia.

Is there a definite thread that connects you series?

Yes. The thread which connects all the series could best be described as “Metanarrative” because the five series have their initial concepts drawn from the great stories of our humanity, stories of myth, religion, ritual, and legend. At the same time these sculptures are equally derived from my immediate surroundings and experiences on Salt Spring Island. I am creating a story within a story so to speak. I’m rethinking how to tell the stories of today without overlooking the rich visual and conceptual history of the past.

‘Girl with Maquette Pan’

Can you explain the importance of your initial training in South Africa?

My art training began with one year of drawing. After this I chose sculpture as my major and ceramics as one of my subjects for my MFA. My ceramics lecturer, Hylton Nel, would show me a Chinese sculpture or bowl and simply say “look at this.” The language of art is visual. He taught me to build on that. Hylton was very connected and eclectic. There was always this excitement of discovery about him.

I watched the apparatus of state at a point of collapse. That is why I sought an even balance between beauty and truth. I needed to think that way in the studio in contrast to what I was experiencing out there in life. As a South African the issues of the day have influenced my artwork more than contemporary sculpture has. The experiential knowledge of living with such violence, poverty and suppression has and will always inform my artwork. It afforded my work a respect for context and truth and my work is different from my peers as a result.

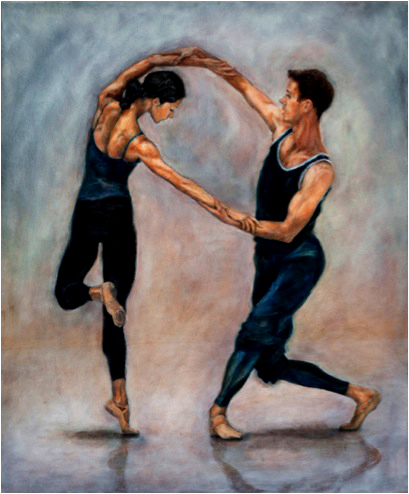

As a child you were interested in ballet, do you think this was the initial link with your interest in the human body and the movement of the body to your work?

‘Batavia’

It’s the same thing, whether it is focusing and developing the movement of my human body or the clay figurative form to describe an attitude or tell a story, I learned through both disciplines the eloquence of the body and how receptive we are to interpreting even the smallest movement or positioning of the head or hand and, in antithesis, how responsive we are to weak, insincere or superficial rendering of the figurative form. The most important, early, lesson I learned from ballet was discipline itself. Staying with the idea and honing it for years until it says a little of the depth I see in nature.

How do you title your work?

These come from places in my past that I have loved or have been important to me in some way. They could be words lifted out of books I’ve read, concepts about the subject/content, or references to ancient political systems.

You have been very lucky with the beautiful catalogue – do you personally document your work?

Thank you. The photography of the artwork for the catalogue was done by a fellow islander – David Borrowman – and the rest were taken by Deon.

‘Tokai’

How important do you think it is for an artist’s actual daily feelings about their work to be documented for history?

My own daily feelings are irrelevant to my work and haven’t been influential, because, in the studio, there is no mystery of heightened awareness – only work and thought. There is the participation in the life of the subject, a view of the collective through the singular, within the silent dialogue between the model and myself. There is an ancient discipline of creating an artwork between artist and model and it is one which can never be fully explored, in face of the limitless diversity of the human form and psyche. The individual, her presence and attitude are life affirming. I also don’t think of my work in terms of individual, completed pieces. The ideas in one work will flow over into the next and inform the development there. All my work is one process that will never reach completion. It is this process that interests me. I’m satisfied with that.

Can you discuss one of your much earlier works ‘Renata’ 1997 and the progression of you work?

The model for this sculpture was a transient young woman from the Czech Republic. She seemed to feed her mind only, not her body. She would save every penny, sleep in the bush, bathe in the lake, then buy expensive tickets to the opera. She embodied the resilience of her country, such a desire for cultural development in spite of difficult circumstances, and the lack of funds to support it. I admire her combination of strength in frailty. I choose models who embody qualities that are often overlooked in our fast paced culture. Character and intrinsic beauty is deep seated and it is a thrill to find where this is visible in the body of the person I’m looking at.

‘Only Now’

On a more simple level, can you discuss your studio space and what you require technically?

Deon and I each have a beautiful studio space. I don’t require much room for working in clay – but there is a good deal of equipment such as kiln, sand-blasting booth, compressor, dust extractor, fans, benches, banding wheels, boxes of clay, bags of sand and a hydraulic lift.

‘Kathy in her studio’

You have very good contact with curators, gallery directors and museum directors. Can you give some insight into how you have fostered these connections?

I was very fortunate to win the eye and support of Dr. Charles Mason. He has shown so much enthusiasm and respect for my work and, although he is no longer with the Gardiner Museum, this support together with countless months of assistance, support and advice from Deon, has led to the success of the exhibition Life and its future travels to other museums.

Kathy with 'Coup d’Oeil

’

Contact Details:

Website: www.kathyventer.com

Email: dkventer@gmail.com

23 – 315 Upper Ganges Rd.,

Salt Spring Island, B.C.

V8K 2X4

Canada

Kathy Venter, Salt Spring Island, Canada

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September, 2013

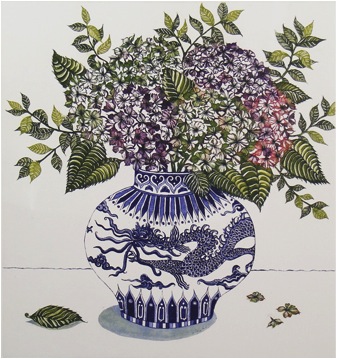

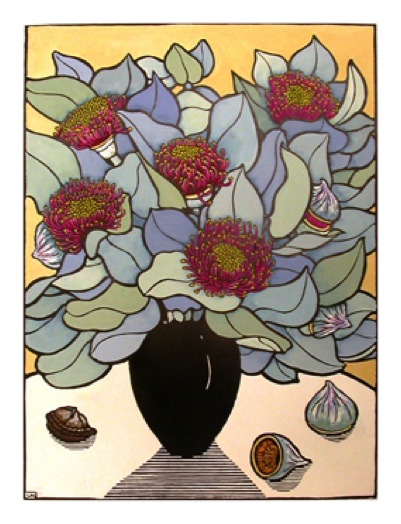

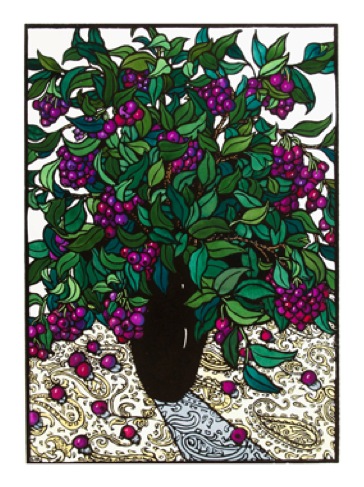

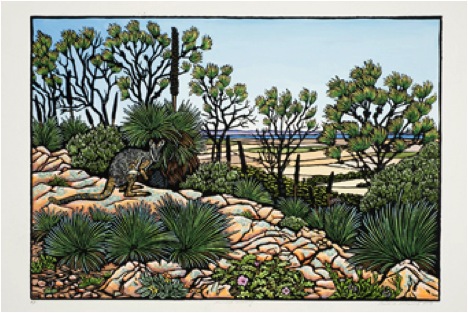

Janine Partington

How did you initially become involved in enamel work?

It was after the birth of my second child. I wanted to get out of the house for an evening a week. My husband Matthew was working with Elizabeth Turrell at the University of West of England, UK. Elizabeth is an internationally renowned enameller and he had done some workshops with her. Matthew thought that I might like to try enamelling too and there was an evening class at our local school of art and design which unusually specialised in making panels. I tried it and fell in love almost at first try – I think it’s the immediacy of it and the quickness of the process.

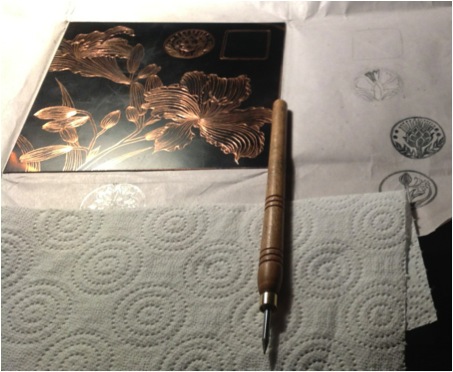

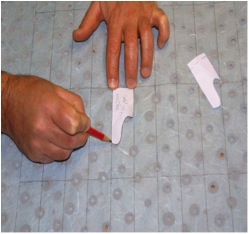

Can you briefly explain what is involved in making an enamel piece?

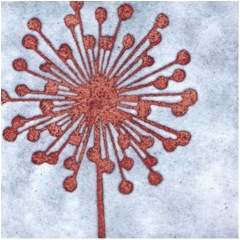

Enamelling is the art of fusing glass on to metal. I create intricate hand-cut stencils that I then lay on to a copper.

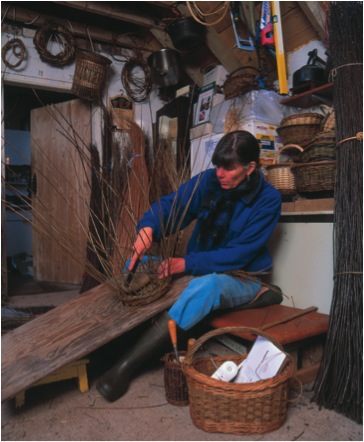

Placing the stencil

My stencils are inspired by trees, flowers, seed-heads and the landscape.

Shifting over Stencil

After sifting the powdered enamel over the stencil, the stencil is lifted and the panel is placed in a kiln at around 800 degrees for a minute or so. Firings are short, and repeated depending on how many colours I am using.

First firing

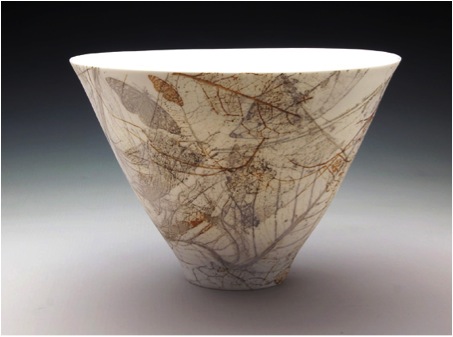

Can you discuss the commission you had in 2012 for Frenchay Hospital NHS Trust, in Bristol?

I believe it is unusual for a commission in a public space such as a hospital not to involve tenders or workshops with staff or patients, but I was invited to make a piece for an interior exterior courtyard and given free reign. I was inspired by the leaves that had blown into the courtyard from the outside of the building, and took the leaf shapes and related seeds and cones etc and supersized them for the large wall. The pieces were waterjet cut for me by Swansea University and then I enamelled the pieces in my kiln. I made the pieces so that they were the largest size that would fit in my kiln. I chose the copper coloured images so that they would reflect the light during the course of the day.

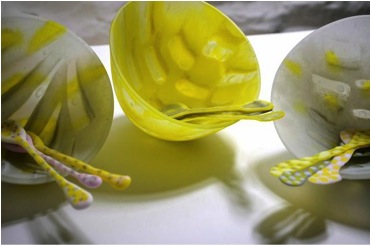

Shape is very important to your work, can you expand on that?