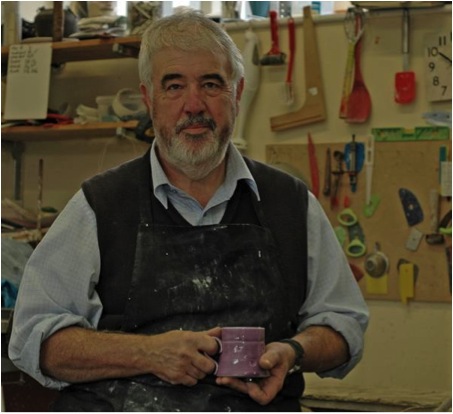

Gráinne Cuffe

Can you discuss the techniques you are currently working with?

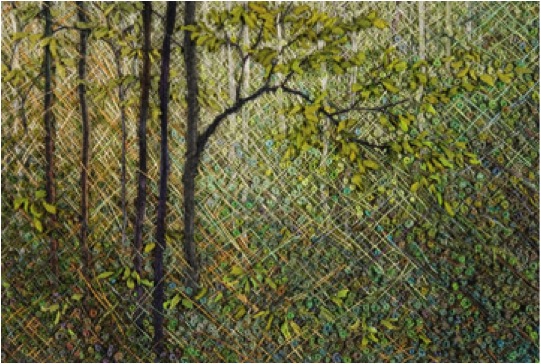

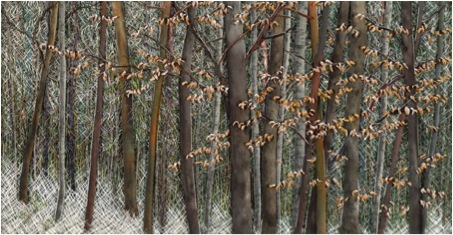

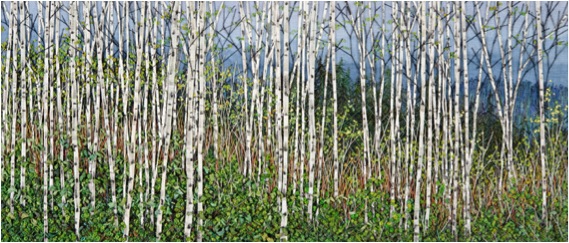

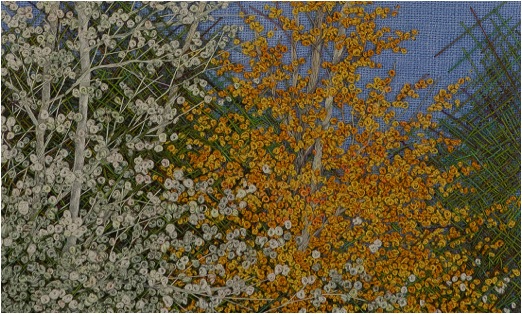

I am currently working with traditional etching techniques: aquatint and line. I use Ferric acid, and work on copper plates.

Over the years you have taken inspiration and academic direction form far and wide. Discuss the importance this diversity has had on your art?

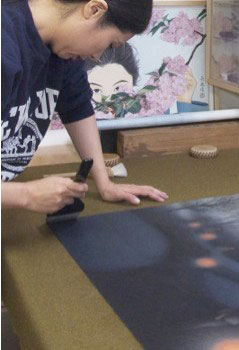

Especially as a younger person, I felt a huge need to leave the comfort zone of familiar surroundings, be that studio or home town. An appetite for academic direction led me to the Tamarind Institute, in New Mexico, where I successfully completed a Master Printer course in Lithography. In hindsight, even more formative an influence than the Tamarind experience was the Fulbright Scholarship with was a brief visit to Gemini Editions in Los Angeles, where I saw gorgeous huge etchings of David Hockney’s beautiful simple silhouettes, profiles of heads. These etchings were approximately 4 Feet x 4 Feet. Plus an exhibition of James McNeill Whistler’s etchings, in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which I saw on the return leg of the Tamarind trip to the States, was also a huge influence.

Every studio I have ever worked in has its own ethics and set of reverences. In Giorgio Upiglio’s Grafico Uno in Milan, an Italian government Scholarship, I was intensely impressed by the woodcuts of Mimo Palladino, their graphic sophistication and simplicity, and mostly the intensity of saturated colour, and their large scale. While Central St. Martins in the late eighties opened my eyes to tonal value with aquatint.

Coming in more closely, can you comment on the influence Norman Ackroyd had on you art?

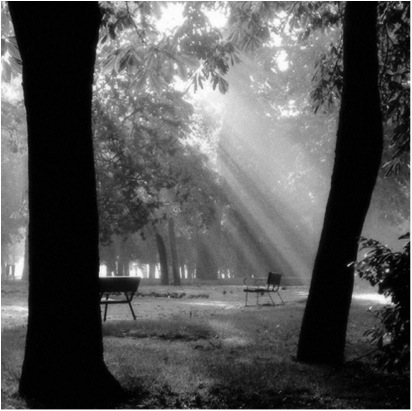

Norman’s theory was that you could get all the colour you wanted using black ink, and white paper. He was strict about this. He taught me for 2 years at Central St. Martins, London. I added a touch of blue, or green to the black, to survive the restrictions. He wanted us students to push those tonal values as far as possible, and using tone to make light/colour. This generated a love of the mesmeric qualities of aquatint.

Norman’s theory was that you could get all the colour you wanted using black ink, and white paper. He was strict about this. He taught me for 2 years at Central St. Martins, London. I added a touch of blue, or green to the black, to survive the restrictions. He wanted us students to push those tonal values as far as possible, and using tone to make light/colour. This generated a love of the mesmeric qualities of aquatint.

The Chester Beatty Museum is a worldwide must-visit while in Dublin and a generous supporter of the art world. Discuss the exhibition and your involvement with the Chester Beatty Museum?

The Chester Beatty Museum is a worldwide must-visit while in Dublin and a generous supporter of the art world. Discuss the exhibition and your involvement with the Chester Beatty Museum?

How did you become involved?

From my first visit as a 12 year old to the Chester Beatty Museum, I had felt a strong connection to the graphic work I had seen there, especially an iconic Japanese screen of staggered irises, a show of Albrecht Durer’s etchings, Mughal paintings, and many precious and beautiful watercolours and prints from Japan. Frequent visits to the Museum never fail to amaze, always feeding the visual appetite for more...this collection has fired the imaginations of many members of the Graphic Studio, and the delights of gardens seemed to be an interest common to both the collection, and to our members.

We felt that collaboration between the two institutions could benefit both, and make for a successful show. Hugely generous with their time, curators of varying sections of the collections introduced the artists to pieces we had not seen before.

What it was like to become a co-organizer of Gardens of Earthly Delight?

It takes a lot of meetings to organise a show like this. It is great to work out all the many details together, and exciting when the show is up and selling. It feels like one is giving back to the Studio. It was a hugely successful show, and a wonderful collaboration between 2 iconic Dublin institutions.

Can you tell us a little about the Chester Beatty (for those who don't know about its collection)

Sir Alfred Chester Beatty 1875 -1968 collected treasures of beauty and wonder dating from 2,700 BC to the present day. Egyptian papyrus texts, Japanese woodblock prints, European medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, Books of the Ancient world…now in this vibrantly run, small Museum. Housed in a purpose built building within the confines of Dublin Castle in the City Centre, The Chester Beatty is always an inviting treasure chest to visit.

What's it like having your work in their collection?

It is a huge honour and I am extremely proud and pleased to have 2 pieces of my work in the Chester Beatty Collection.

You joined the Graphic Studio in 1979. Explain the importance of both the studio, and collaboration with other printmakers has and still has on your art?

The Graphic Studio offers me all these positives:

- Sharing technical information about the work.

- Being in an atmosphere of work.

- Exposure to approaches radically different to one’s own to the making of an etched image.

- A wide variety of visual language in terms of the final image.

- The talk about the making of an image.

- The enthusiasm about visual language.

- The shared love of paper, colour, the end effect.

- The shared fascination of the progress of an etched image from start to finish.

- Constantly meeting Painters and Sculptors who come there to work collaboratively with Master Printers on the Visiting Artists program.

The Graphic Studio Gallery which the Studio owns, show my work.

Collaboration with other printmakers in my case currently means I need to work with another well trained printmaker on the larger pieces because it would be physically impossible to achieve the printing a successful print on my own. The weight of the large plates is considerable. They need 2 people to handle them. It would be counter- productive to work on these on my own. It is at the colour proofing and editing stage that I need to ask a skilled printmaker to work with me. Inking up the plate may take hours, and you have to be time-aware, because some ink colours dry and will not print properly.

Your work is described as BIG can you explain the constrictions that size place on your art within the printmaking field?

The main constriction is the size of the press bed in Graphic Studio. My metre square plates fit easily, with ample room around the plate. As I use my studio in Wicklow for working on the plates, I have recently invested in a wonderful new acid bath from Polymetaal, Holland, which easily fits the larger plates. I love BIG. The generosity and expansiveness is good.

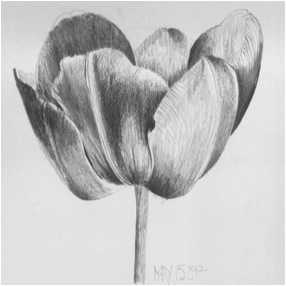

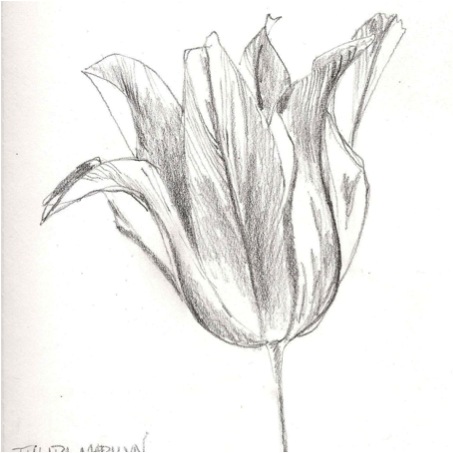

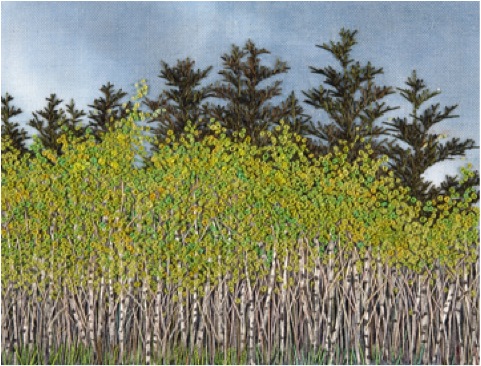

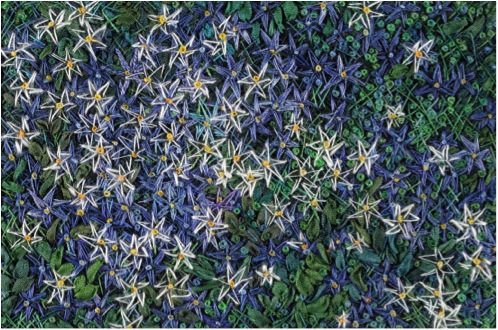

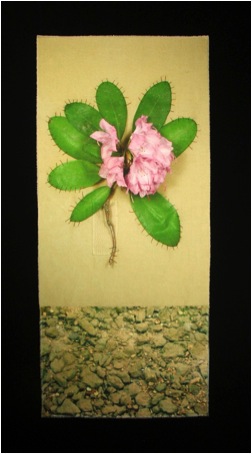

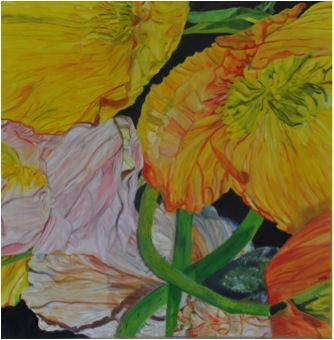

Expand on your work ‘Delphinium 11?

Thinking I was totally finished with Delphiniums, recently having completed Delphiniums I, Delphinium II was inspired by a large stand of wondrously stunning delphiniums on a sunny June day in a neighbour’s garden. The leaves articulation is different to Delphinium I, more 3dimensional, and with a variety of bright greens. The blues and purple-blues are also different. In that garden, I felt a bit more could be said to honour the Delphinium statement. I felt I hadn’t said it all, yet.

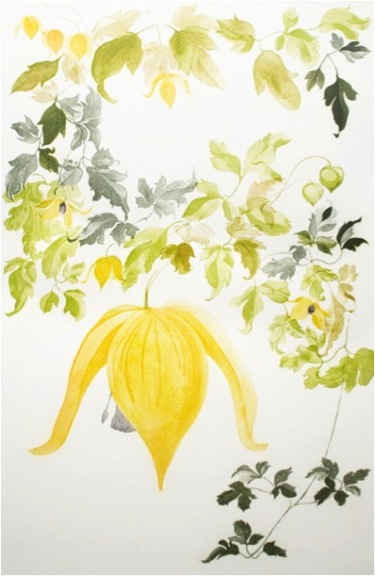

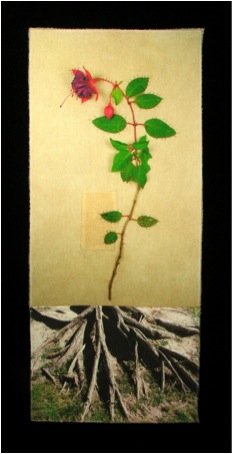

You call ‘Clematis orientalist’ “the big one”. Can you explain this?

Clematis Orientalis III is a large rectangular 4’6”high x 3’wide etching. I have made 2 smaller etchings of the same plant, for A Natural Selection - a show which was originally a fund raiser for the Studio, 100 artists contributing a limited edition print, image inspired by National Botanical Gardens, Dublin.

You work with both plants and flowers how would you categorize your work?

In describing my work, the most accurate words are: Loosely Botanical.

That might be a category?

By adding that Georgia O’Keefe, the American painter, has been an influence will give a sense of clarity.

I have never been able to describe my work with accuracy, using words.

Your work has such a very strong Botanical aspect, discuss?

Adding in explanatory elements of visual interest is a nod towards Botanical illustration of the past, where much information is on the page. My extra elements are there because they balance a composition, and are very carefully balanced in themselves. They are not intended to be botanically accurate. Some plant elements are extremely sensuous visually and although tiny, are magnificently beautiful: wonders of design, and the Bauhaus principle ‘Form follows function’.

Adding in explanatory elements of visual interest is a nod towards Botanical illustration of the past, where much information is on the page. My extra elements are there because they balance a composition, and are very carefully balanced in themselves. They are not intended to be botanically accurate. Some plant elements are extremely sensuous visually and although tiny, are magnificently beautiful: wonders of design, and the Bauhaus principle ‘Form follows function’.

When working on both exhibition layout and print size how do you decide on the size of the work?

Exhibition layout is usually a balance between large and small works, depending on the constraints of the gallery. In deciding about the size of an etching, if I feel an image of a plant will make an adequate visual impact, then the large format will work. At the drawing stage this is assessed. Drawings may start on a small scale, then develop into a larger format. The plant also has to have enough visual drama to hold its own on a large scale. Often, holding a magnifying glass to a plant is the only way to see the detail.

Exhibition layout is usually a balance between large and small works, depending on the constraints of the gallery. In deciding about the size of an etching, if I feel an image of a plant will make an adequate visual impact, then the large format will work. At the drawing stage this is assessed. Drawings may start on a small scale, then develop into a larger format. The plant also has to have enough visual drama to hold its own on a large scale. Often, holding a magnifying glass to a plant is the only way to see the detail.

If you want this detail to be a part of the image, scaling up is the only solution. Degrees of admiration and wonder and recognition of a magnificence [to do with the visual impact] play a part.

Where do you find your subjects (plants and flowers)? Are you, like many, a keen gardener?

Where do you find your subjects (plants and flowers)? Are you, like many, a keen gardener?

As a great admirer of the world of plants and flowers, yes, my subjects are mostly from my garden. If I was to let myself get swallowed up by my very wild garden and the notions it inspires, I would never get an etching either started or finished.

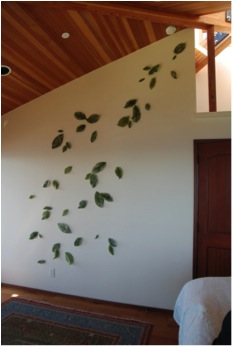

Many of your works can be found in hospitals and also at the Dublin Family Law Courts. Do you see your work as calming? How would you describe it?

Many of your works can be found in hospitals and also at the Dublin Family Law Courts. Do you see your work as calming? How would you describe it?

Some of my work is calming. I relish calm. In calm, I get space to think thoughts, have new ideas, and make progress with the etchings.

Calm lets people breathe about the goodness of themselves, potential for happiness and positivity of life.

When the ingredients of balance, calm, sensuousness are at an optimum in a piece that is when I feel it is acceptable. A visual harmony has been worked towards and concluded.

Although being collected by Museums etc. is wonderful, having my work in places where people are stressed is important to me. I have had excellent feedback about my work in the above; a settling down of upset and raw nerves.

Contact details

grainnecuffe@gmail.com

http://www.grainnecuffe.ie

Gráinne Cuffe, Dublin, Ireland

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, October, 2014

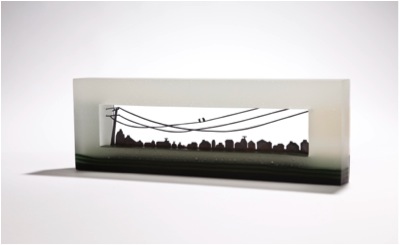

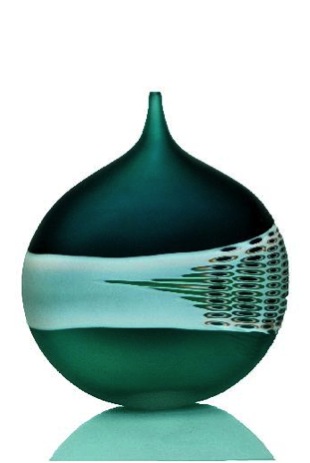

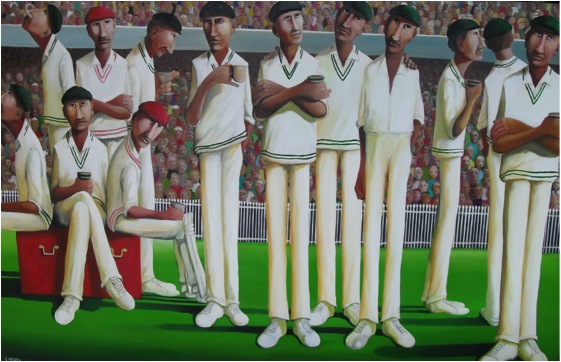

Latchezar Boyadjiev

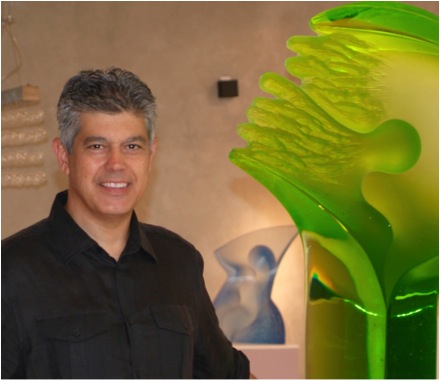

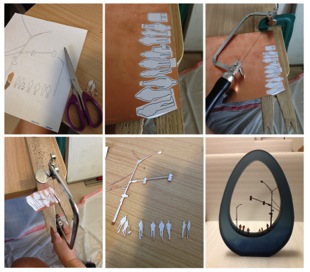

Originally you worked in the field of optical glass, can you explain this process and the type of work you were able to produce using this method?

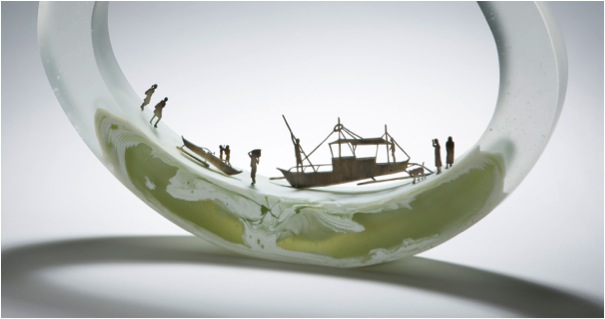

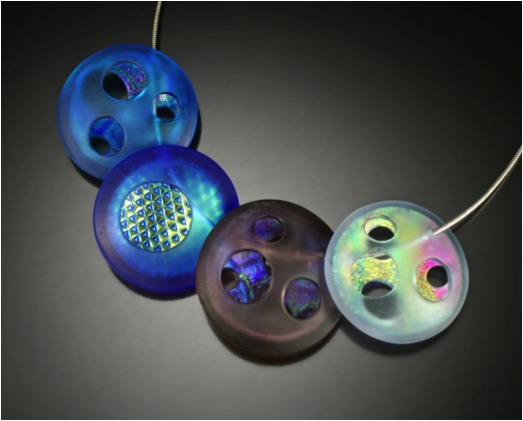

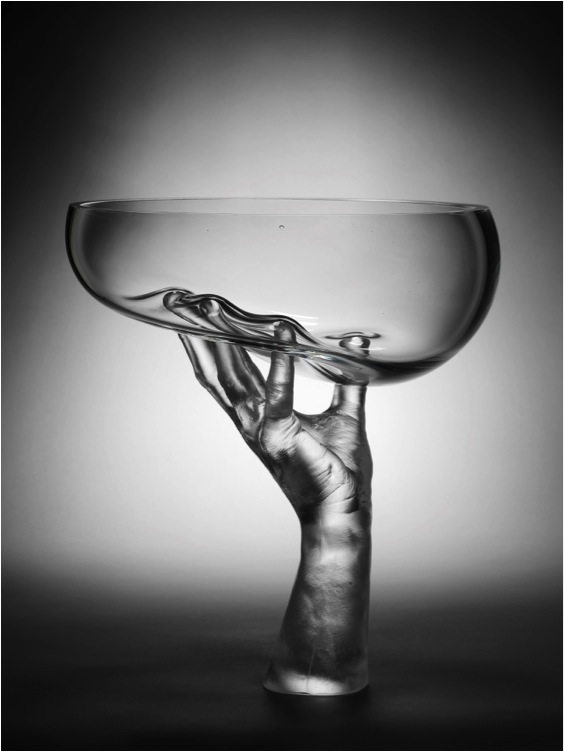

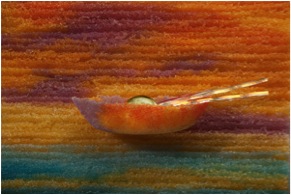

The term optical glass comes from using optical glass to create my sculptures.

I was using glass segments to construct my pieces. They were mostly clear optical with inclusion of coloured glass segments to bring a little life to the coldness of the crystal.

Each segment was cut according to my drawing and ground, fine ground and polished. After finishing the sections I was gluing them together with an opticly clear adhesive.

Why did you change to cast glass?

I was limited by this technique regarding size and colours. I wanted my work to be more dynamic and have great impact on the viewer.

I always wanted to try kiln casting and after a visit to the Czech Republic in 1996 I started casting my work there.

It was a in collaboration with the Czech Foundry that lasted about 15 years and is still going even though I started casting my work in my studio in California.

Can you take us through the process you use now from drawing, clay modelling to the final cast glass piece?

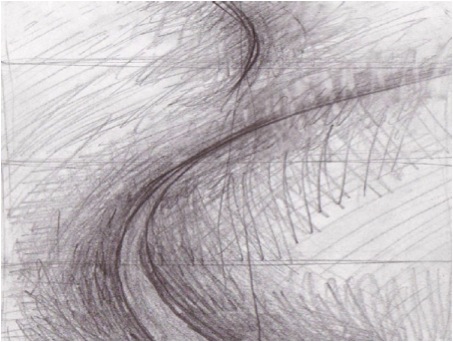

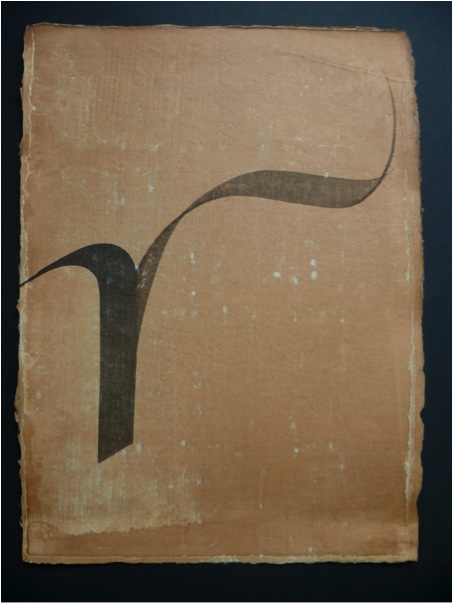

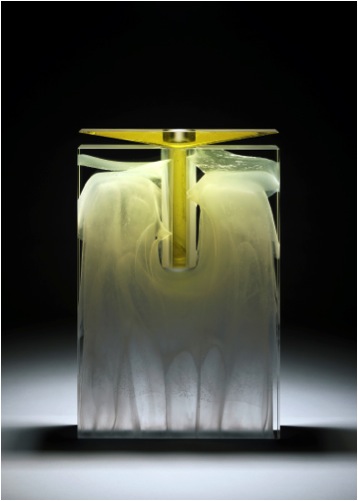

First and most important is the drawing. I spend a lot of time drawing on a craft paper with charcoal. When I like the particular sculpture I start modelling with clay. After the clay is done I make a negative plaster mould and then cast the original in plaster.

I grind and make the plaster positive perfect as I want it to look in glass. From the plaster positive I make another negative mould for glass using silica sand and plaster.

After the mould is dry I place it in a kiln. Than I measure the right amount of glass needed and load the mould with coloured glass billets which are in a shape of 8”x8”x1” thick tiles.

Then I program the kiln computer to adjust the temperature and annealing times depending on the thickness of the glass – the thicker the glass the longer the annealing is. It usually takes two to three weeks to melt and cool a sculpture.

After the piece is done than the hardest part is to finish the surfaces. It involves a lot of grounding, fine grinding with diamond tools, polishing, sand blasting and other finishing techniques.

You personally take your plaster positives to The Czech Republic, why?

I have been doing that for 12 years. It was easier to pack four plaster models in two boxes and take them as a luggage than to ship them. Also I wanted to talk to the foundry people in person choosing the right colours and finishes for the pieces.

Not only has your glass changed from optical to cast, your drawing material has also changed from pencil to charcoal. Can you tell us why?

Pencil drawings are great for smaller designs. When you get to draw life size of three, four feet sculptures the pencil becomes an obstacle – it slows me down.

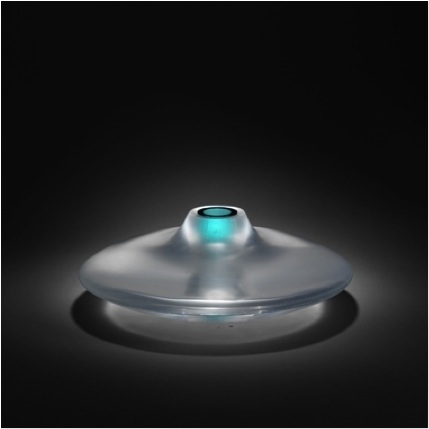

Can you discuss the way you use a combination of glass and metal in ‘Radience’ / 'illumination'?

I wanted to introduce a light in my sculpture and designed a stainless steel structure with a built in LED light. The light is shooting up through the glass and illuminates it. It comes alive – almost like fire in a torch.

‘Illumination’

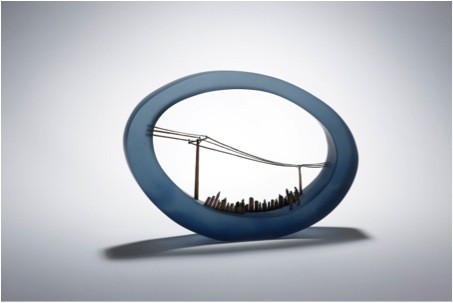

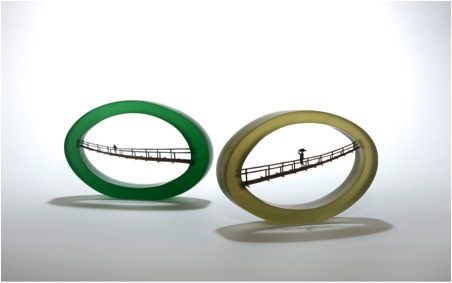

Shape and colour describe your work; can you expand on this?

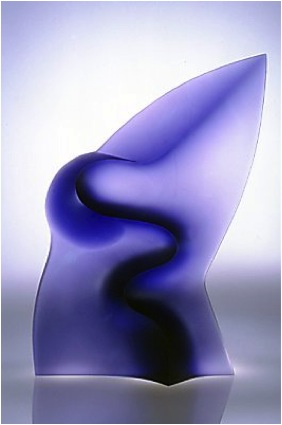

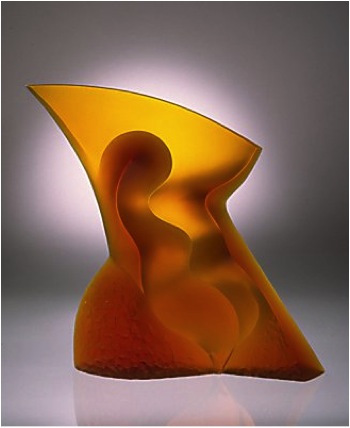

Glass is a cold material. I am trying to soften the crystal structure appearance of the material. Giving it dynamic shapes, combined with fluidity and vibrant colours to express my feelings and emotions. You can take any two pieces of my work and find out about it.

The piece ‘Pursuit’ shows the control you have over glass and how you have the flow of colour within the piece. Please discuss?

The flow of the colour is achieved by controlling the thickness of the glass – the thinner it is lighter and the thicker – the darker.

‘Pursuit’

It is well know that you deflected to the United States via Italy in 1986. How does it feel to have to come from this position to having your art in residence at the White House, in Washington DC?

It is my dream come through. I came here after being in a refugee camp in Italy for few months. Arriving with $65 in my pocket and very limited English. Finding work with glass right away and opening of my studio in 1988 was very hard but rewarding.

Being part of museums and private collections including the White House was very rewarding.

‘Creation'

Your work was first introduced at SOFA in 1996 - how has this affected your career?

Actually it was 1991 and the time was named New Art Forms. It became one of the highlights for the year along with the solo shows I had in galleries representing my work.

'SOFA display 2003’

For those who do not know, can you explain about SOFA?

Sofa is the most prestigious art fair for contemporary Sculptural and Applied arts around the world. The top galleries from around the world are exhibiting their top artists. The show is only four or five days in the Navy Pier Convention Center in Chicago.

With a piece like ‘Emotion’ you have had it cast in many colours. Explain how many castings you make and how you choose the colours?

‘Emotion'

I do up to six castings of the same design but in different colours so no piece is ever the same. Some designs are only a single casting, some two or three. It is very rare to have 6 castings from the same design.

Your statement, “I want my work to become a part of modern architecture and a contemporary environment to reflect the era we live in”. Can you expand on this?

At the moment I am working on developing and finishing larger castings up to 7’ in my studio in Marin County. Ultimately they will become part of modern architecture and be viewed by many people and not only by few selected collectors.

Can you discuss one of your Commercial pieces and one Residential piece?

I do not make any difference between both. Each one is my work and I put my best to achieve whatever the task is.

In 2008 you had an exhibition at the Academy of Art in Sofia, Bulgaria This took you full circle; how did this feel?

It was great to come back to where my roots are and where I began drawing and sculpting.

It was covered by all media extensively and was the first large exhibition of glass sculptures in Bulgaria ever.

‘Quest'

You constantly exhibit, how far ahead do you work with your exhibition program?

I work with year to two ahead scheduling exhibitions and planning my future work.

I always plan ahead but I am ready to face any challenges that always come when you are pushing the limits or the economy affects the sales.

One of my favourite mottoes is:

“Plan for the best but prepare for the worst!"

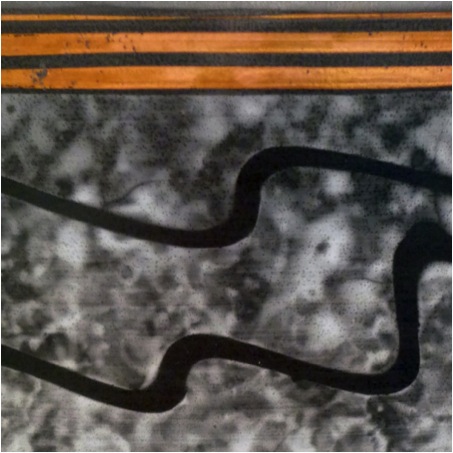

‘Stream'

Contact details.

Latchezar Boyadjiev

5498 Nave Drive

Novato, CA 94949

415-883-2025

Website: www.LatchezarBoyadjiev.com

Latchezar Boyadjiev, California, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September, 2013

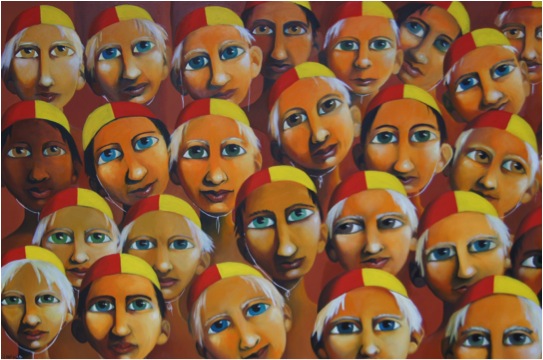

Vally Nomidou

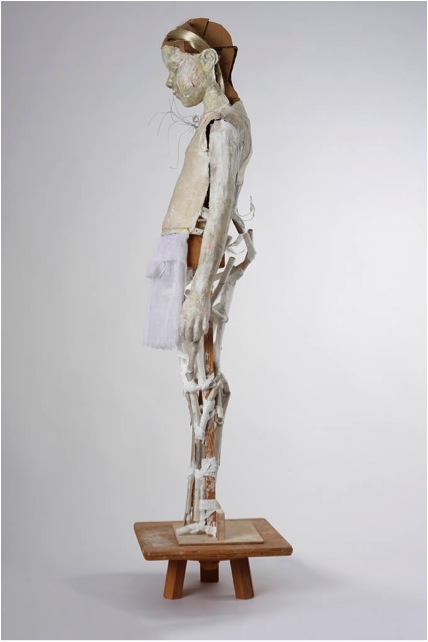

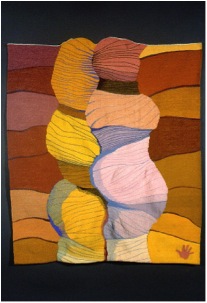

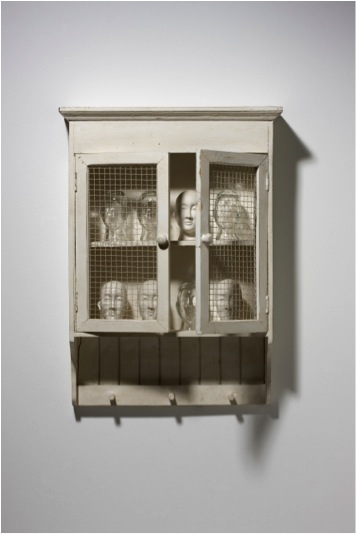

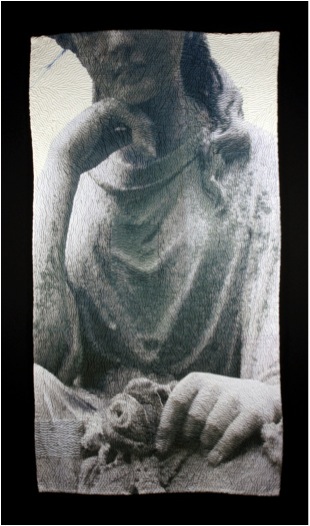

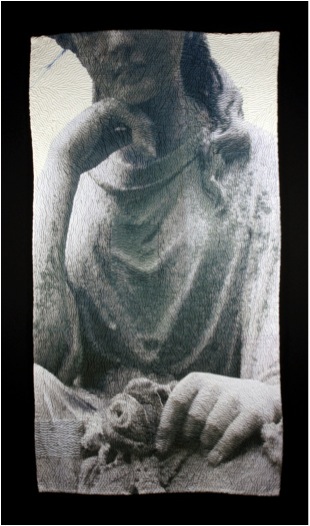

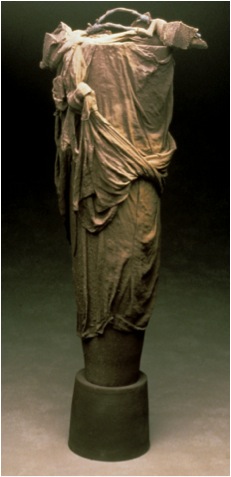

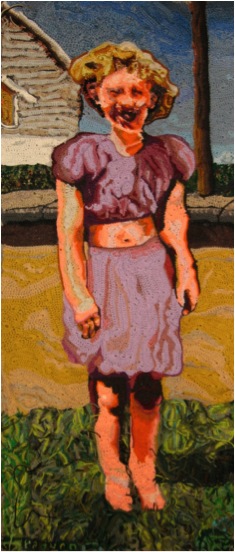

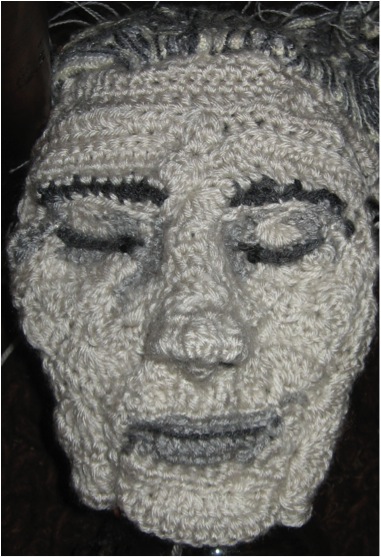

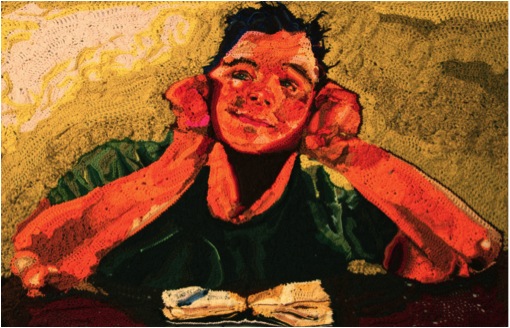

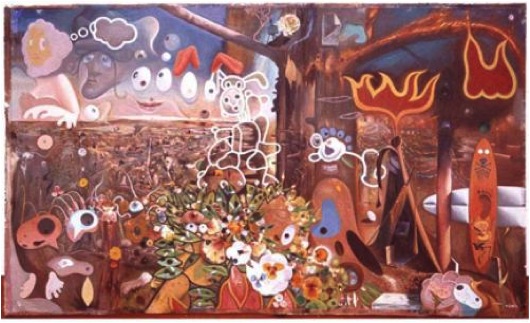

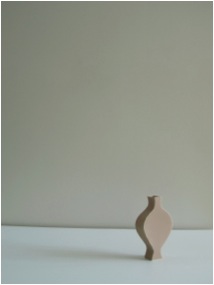

Your exhibition ‘Let it Bleed’ is made up of female forms. Can you explain the vulnerability you have been able to portray?

Fragility is the way women artists insisted to present as a plastic value in the 20th century. I worked out my figures spontaneously with the intention to show the mental state of ‘'between’. Between different trends, orientations, routes, decisions. The situation to be between and to do connections, fragile connections with a variety of possibilities, with uncertainty. Without a final decision. With tyranny. The difficulty, the sensitivity, the contrary emotions that coexist, the agony, the empathy, the cowardice, the fear. The game and the pleasure to express all this situation sometimes gently and sometimes hard. That wonderful 'embarrassment' in routes which you discover surprisingly. All these are a fragile world written on the female body which I build.

How many figures were in the exhibition?

There were seven figures in the exhibition, two small heads and a flower hand as well.

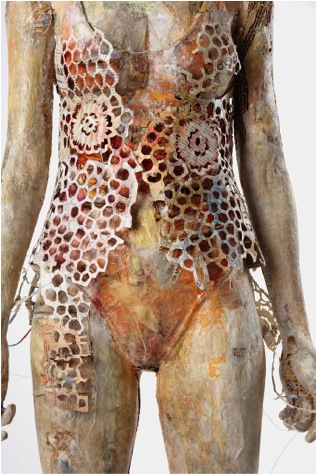

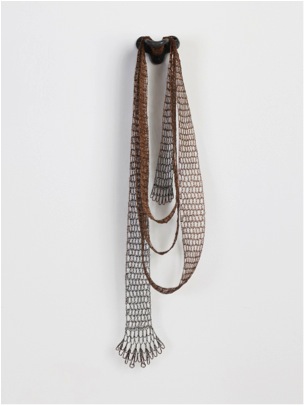

Can you expand on the use of stitch in the work?

Stitch as the meaning of the word describes, can be sewing, stitching (difficult, unnatural union) suggesting wound: wounds and holes (an emptiness). Mental gaps, wounds, difficult compounds that can be shown as wild jewellery, as strange rhythms on the figure. Stitches, episodes of soul and form.

Explain the building process in your figures?

I choose the person and I think with my senses what is that I want to show. I imagine postures and I try postures suggesting an unbalanced situation. We photograph all around the figure. I get molds partially from different parts of the body. I photograph gaps and compounds of the molds. I collect my molds on a table. At this stage I start my paper sculptures.

I create a colored palette collecting papers. Toilet paper, handmade paper and old newspapers. I make layers from paper inside the molds with acrylic glue and paintbrush. That means that I decide before which colour my figures will have.

With a specific printing tool I stick cardboard inside my mold. After drying I get my figure out of the molds .At the end I have many parts of paper forms. Then I start building. I connect the parts using cardboard till I create a whole figure. The difficult and beautiful work starts now. I use wooden tools to work with my figures. Knives, rasps, files. I work the whole form adding and removing again and again.

Who are your sitters and the personality of your figures?

People I know, anonymous people, simple people, children, (my son, a refugee girl, a lonely girl with a famous family) an abnormal dancer...

Why have you placed some figures onto forms?

They are abandoned and beautiful bedded in morbidity.

Can you discuss the personality of your figures?

All of them have something vulnerable. They are personalities under formation, defenseless against their fate. The women usually have a narcissism covering their despair.

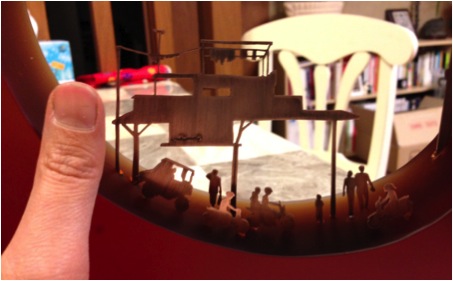

Explain the fragility of #15 by both her age and position?

The same person express the abandonment, placed on the shelf, on high level, marginally placed on the edge.

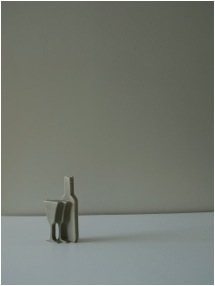

In #19 you have left a large area showing the base, discuss this?

It is the same person again, created without any purpose to hide something or to become a plastic value. It is abandoned so to be exposed her draft construction of her structure. With that way it is given a tension to the breakdown of her personality and her individual construction. There is an emphasis to the coincidence and the deficiencies that create that image. That drama is emphasized by the base, which is a working base, and as a memorial stand. It is a contrast, an exaggeration. Let's say it is a hymn to those who face difficulties and harm in their childhood.

Also on #19 colour is more prominent, can you explain why?

All the material on that sculpture are unique and natural, as I found them. With their own identity and colour.

#20 and #21 you have not constructed whole figures rather a head and hands discuss this part of the exhibition?

#21 is a symbol. These parts of the figure are changed and separated from the whole sculpture. #20 is a small head another version of my figure portrait.

#20 is a small head another version of my figure portrait.

What lead you to limit you work to paper?

I love paper and its history. I like it because it comes from East and from the European Middle Ages tradition. It a light material. (It’s not belong to the traditional culture of sculpture). I reminds me maps, miniatures sensitive and light objects that show and describe real and imaginary worlds. It is light, recyclable and it has history. I love its discretion.

What are you currently working on?

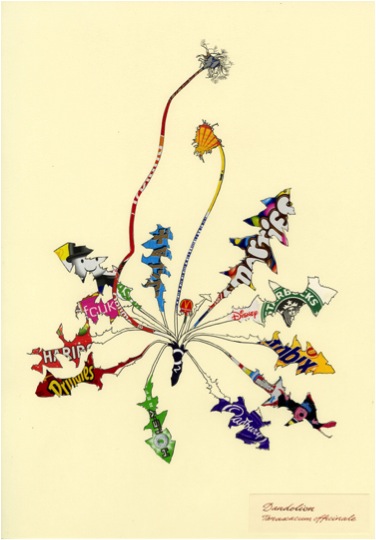

I am working on projects, work on paper and some artist's books (thoughts and feeling diaries) and botanical drawings.

Contact Details:

Email: nomidouv@yahoo.gr

Vally Nomidou, Athens, Greece

Translation by Apostalia Tasiou

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September 2014

Gary Drostle

How did you come to work in this particular medium?

After leaving Art College in 1984 I knew I wanted to work outside the gallery system, in public spaces, this was for me a rejection of what seemed a narrow and elitist system. I began to paint murals, but working outside on the street is a much harsher environment than a gallery and issues of durability and lightfastness became important issues. When I discovered mosaic art in 1990 this immediately solved those problems. I hunted for all the information I could find about most and basically taught myself from books to undertake my first mosaic commission. Initially I continued to work as a mural painter whose medium was mosaic but increasingly, as I have used and explored the medium of mosaic further, the medium of mosaic has gripped me and drawn me in. Mosaic has so much more to offer than the simple translation of a painting, it contains a beautiful and mesmerizing world full of patterns, textures, light, pure colour, expressive use of cutting and laying, the cohesion and breaking apart of the image… So much more to yet discover.

Discuss the different techniques that are required for mosaic. The distinction is not really about 2D or 3D but about flat mosaics verses not flat mosaics.

All floor mosaics need to be flat, and sometimes wall or panel mosaic are wanted flat too. The technique I used to achieve a flat surface is known as the paper-faced indirect technique. This process really begins with the cartoon, a full size drawing of the design on paper - however the design is drawn in lateral inversion (mirror image). Once this is prepared the mosaic tesserae are cut by hand and individually glued faced down onto the paper design using a simple flour and water paste. The mosaic is constructed in this way, if it is large it is cut between the tesserae into manageable sections as it is completed. Once the whole mosaic is complete it is transported to the site where it is flipped upside down and placed into fresh cement on the floor or wall. The paper, now on the top, is then damped, releasing the glue. The paper is then removed and the mosaic is left bedded in the cement. It just remains then for the mosaic to be grouted and cleaned.

This is a great technique for making mosaics, allowing construction in the comfort of the studio at any time of the year.

The technique used for 3D and for 2D mosaics that one wishes to have texture is the traditional direct method. Nothing could be simpler than pushing the tesserae directly into the setting mortar. It is the essence of pure mosaic making, giving ultimate control of texture and light on the work and allowing the artist to express the physical nature of mosaic directly with the hand. It is a beautiful way to work in mosaic.

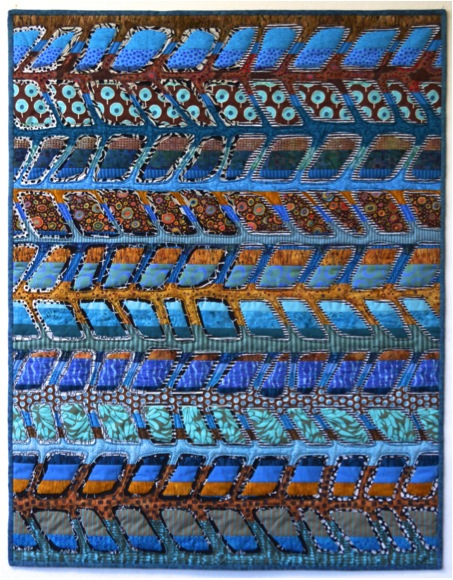

It was through your work, ‘The River Life’ that I became aware of your mosaic work. Can you discuss the meaning behind the work, how long it took to lay and the number of people involved in the project?

The River of Life mosaic was probably my favorite work to date, perhaps particularly because the client, The University of Iowa, really showed great trust in me to create a work that I believed would work best. A committee that is willing to have faith in its appointed artist is unfortunately very rare, but I do believe that giving the appointed artist freedom to create the best they can is the way to get the best work and Iowa University was such a client.

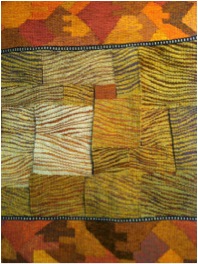

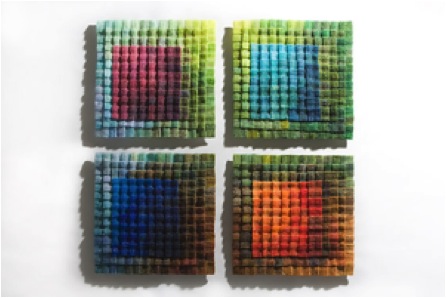

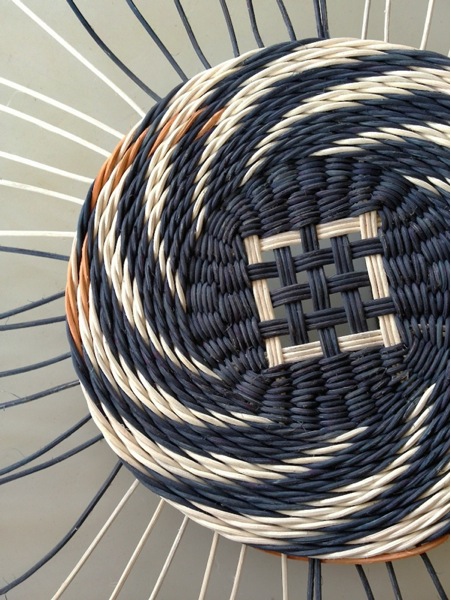

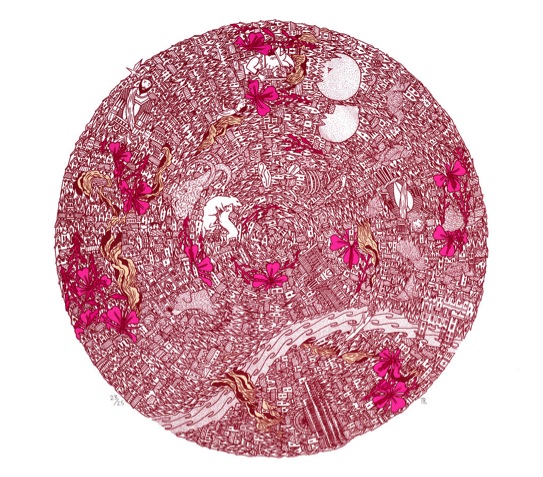

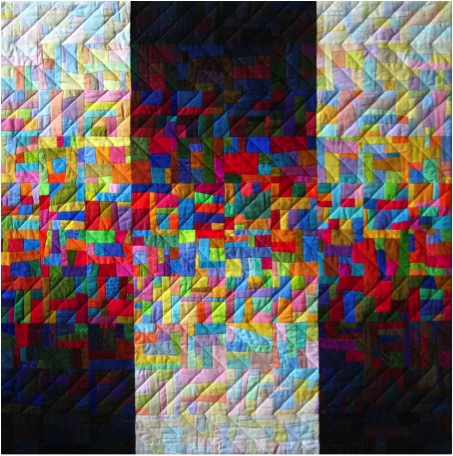

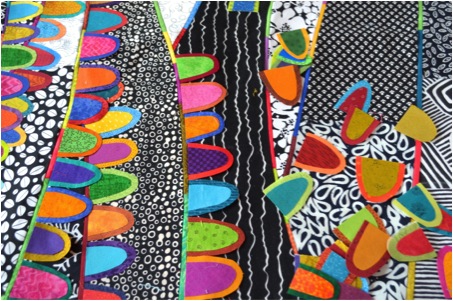

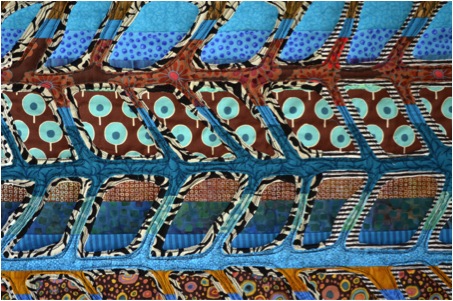

Like most of my public, site specific commissions the starting point for this project was the site itself. I began looking at the function of the building, the campus health and fitness center, and its philosophy of Wellbeing. Then I looked further out and the terrible floods in Iowa City that instigated the building of the new center, and the meandering river itself, then to the communities around it and in particular to their textiles, the Amish quilt making and the First Nation Iowa people and their textiles, also the basket weavers of the local area.

When it came to drawing all this information together it began as a struggle but then there was one of those eureka moments (as I sat staring at an aerial picture of the Iowa River) when everything just fell into place. For me the River of Life sums up these diverse ideas all together with so much more. I imagined the source of the river being birth, with the life lines of people’s lives running along the river as individual courses of tesserae. The pattern fields of the surrounding countryside formed the background through which the river flowed, made up of those textile patterns. The central golden section of the patterns represented Wellbeing, a life in balance, whilst the grey outer sections represented life out of balance. The life lines of the river tracing their way through, sometimes bursting its banks as some lives go ‘off the rails’. It all fitted together beautifully.

As this was a large mosaic I needed help to construct it. I worked with a varying team of about five at any one time during the six months construction using the indirect paper face technique in my London studio. For the installation I and one other came from London and we were joined by two US mosaic makers to install the work over the course of two weeks.

For me this project was a great success as it worked on so many levels from the design to the technical and most importantly the functional success of the work for those who use the center.

Can you discuss one of your earlier works and the importance it has played in your career?

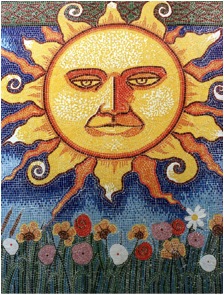

When I think of past mosaic works that may have marked changes in my work two pieces spring to mind, the Sunburst mosaic for Islington in North London and the Fishpond mosaic for Southampton East Park.

The Sunburst Mosaic was my first mosaic. It was commissioned by Islington Council and was basically an extension to an earlier painted mural commission to the extensive underpass network. Islington Council showed great trust in allowing myself and my colleague for that commission, Ruth Priestley, to create a mosaic based purely on our painted commissions. We made the vitreous glass mosaic in the attic of my father’s house using the paper faced method, it was a huge learning experience and set us both off on a new voyage of discovery and love for mosaic art.

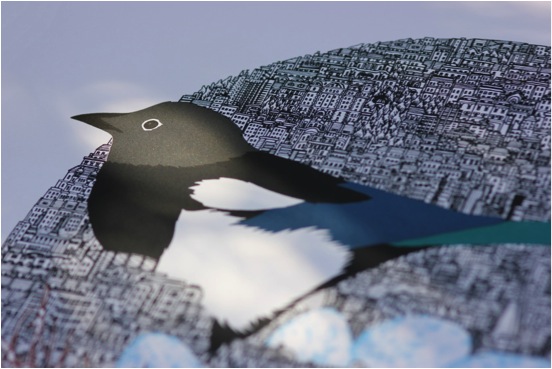

The mosaic for Southampton East Park was commissioned in 2005 and was significant for me for one particular reason. The commission through a landscape architect was to make a 9 meter diameter mosaic which was to be designed by another artist, Caroline Ishghar. The commission came at a point when I was working with artist Rob Turner and our studio was doing well, we were confident of our design, fabrication and installation of our own mosaics.

When the design for Southampton arrived in the studio it was a small loose painting, unlike our designs to that point it paid no heed to the palette of available colours or any ideas of classical andamento - this was a big challenge but the process of translating the design into mosaic made me realize how much more was possible in the medium and it became realization of a new freedom in creating mosaics offering a greater freedom for future designs.

Can you explain the logistics needed to produce ‘Entwined Histories’?

The ‘Entwined Histories’ mosaic sculpture was commissioned by Poplar HARCA, a public housing developer in east London.

For me this commission was great fun and I hope a good example of how site, history, creativity and community can come together to realize an artwork that is truly site specific. As always the commission began with research into the local areas history, in this case picking up on the fact that the area was the former site of the major rope makers for the London Docks. The other factor that was important about the local area today was the large Bangladeshi community. This area of London, because of its proximity to the docks and correspondingly its large stock of poor housing, has always been a focus for migrant communities coming to London dating back many centuries including the French Huguenots, Irish Weavers, Chinese Sailors and Ashkenazi Jews. These communities settled in east London and made it their home, many often working in the textile industry. This of course sparked links to the earlier River of Life project. So I designed this large rope form, with each strand of the rope representing a different community in the area using a textile pattern associated with that community. I saw this as a perfect expression of how the larger community worked, each through its own strand keeping its identity but all binding, uniting to form a stronger whole - I was happy with this positive view of our multi-cultural neighborhoods. At the top of the sculpture the strands turn out to the world revealing a golden interior, I saw this as the result of the nurturing community enabling its members to grow and aspire to greater things.

Making a sculpture like this is always a challenge. I carved the polystyrene form around a stainless steel frame and then coated it with glass reinforced concrete. Once this was dry the mosaic process began, working directly onto the form the tesserae were cut and stuck to the sculpture. Once the mosaic work was finished the sculpture was grouted and cleaned. The sculpture included a lifting hook in the top and a fixing plate on the base allowing it to be hoisted out of the studio, transported to the site bolted into place.

Discuss the importance of the Mosaic Arts International exhibition to your career?

SAMA’s annual Mosaic Arts International exhibition is significant for me because it is the only regular juried mosaic exhibition that has recognized the importance and value of architectural mosaics, which after all is really the essence and birthplace of mosaic art. They do this by allowing photographic entry into their juried exhibition. I am extremely grateful to SAMA for their commitment to architectural mosaics in this way and am very proud that my work has been selected for many of their exhibitions - really it is the only opportunity for me to showcase my work to a larger audience and also to my peers. One of the great things about the world of mosaic art is the very open and supportive nature of mosaic artists, it is a friendly and passionate community.

Explain the overlapping of your work in modern London and the Roman mosaics found throughout the UK?

The Romans were the greatest exponents of mosaic art and there have been over a thousand Roman mosaic floors found in Britain alone. Obviously as a modern mosaic maker I am very aware of our Roman heritage and greatly admire these works. The Romans have a lot to teach us about mosaic making, in particular I admire the economy of their work, the way in which they balance the amount of labor, the detail of design and the cutting of the tesserae. As well as trying to use this knowledge in creating my own mosaics I have referenced Roman mosaics as part of acknowledging the history of a specific site and even just created Roman style mosaics for specific commissions such as those for Chester’s Roman Gardens which were realized in close co-operation with the city’s archaeologists.

‘Woolwich’ has a very personal association for you. Please discuss this?

I was born in Woolwich and have lived there most of my life, indeed I would still be there if it had not been for the loss of my family flat to the recent riots, which was quite a tragedy forcing me to move out of the area. I have a great affection for this unique corner of London. Woolwich has always been a poor working class area, far from the glamour of central London, but it has an amazing history and some wonderful architecture combined with a great multi-cultural community, the whole world is in Woolwich and I feel it keeps me grounded. It is home…

Expand on your personal thoughts about the importance of public art in contemporary life?

For me pubic art is about democracy, it’s about seeing art as a part of all our lives, it’s about seeing all the arts as a vital part of humanity and civilization - we are here not just to work and survive, life is actually about love and play of which art is an essential part. Unfortunately, like much of life now, art is being ‘privatized’, a commodity to be traded, something reserved just for those who can afford it. Genuine public art is the antithesis of the arts combined, it is site specific so cannot be traded, it is open to all. I’m not saying that only public art is worthwhile, far from it, all the arts, painting, sculpture, music, dance, drama, they are all vital. I would like to see a future where art is more prevalent than advertising on our streets, art that fills our world. The problem with public art at the moment is that it is too precious, because of its rarity, and this preciousness leads to over caution. Like the rest of life there is also a battle going on in ‘public art’ as corporate ‘public’ art threatens to replace art generated from communities.

Contact details.

Website:www.drostle.com

Email:gary@drostle.com

Gary Drostle, Central London, England

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September, 2014

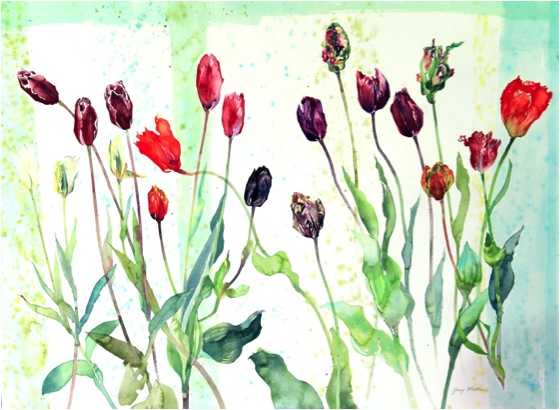

Kathryn Matthews

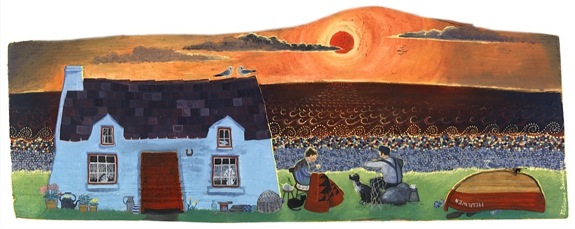

Your art training has been in two countries, The Netherlands and the UK. Can you discuss the differences and how this shows in your work?

The Dutch are more open minded about art in general and painting is not as elitist as it is here in England. I had my first abstract painting classes in Holland which terrified me as I went there straight from A-level college in the UK which is all about painting as realistically as possible.

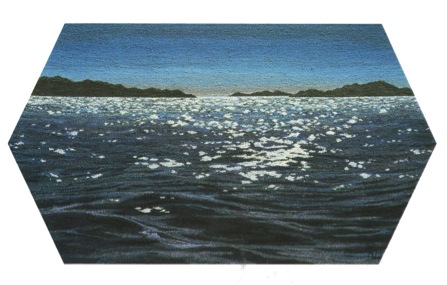

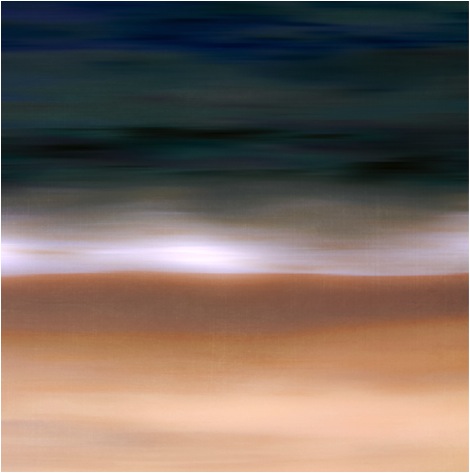

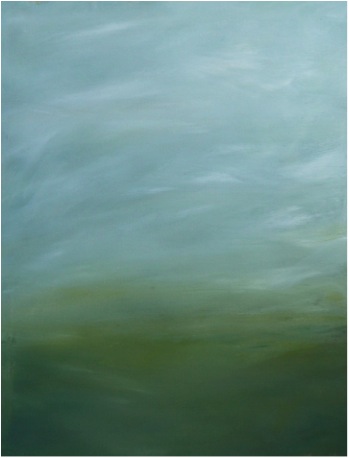

Your studio is in Shoreham-by-Sea. Can you share both your studio (inside) and explain the effect living by the sea has on your art?

My studio and my gallery are both virtually on the beach about 6 miles from each other. From both I have an incredible view of the sea and the south coast. It is ever changing. The beach outside my studio is quite wild with lots of beach flowers. From May – July, the beach is a wash of pinks, purples and blues. In the summer months I swim a lot which helps me focus on my work.

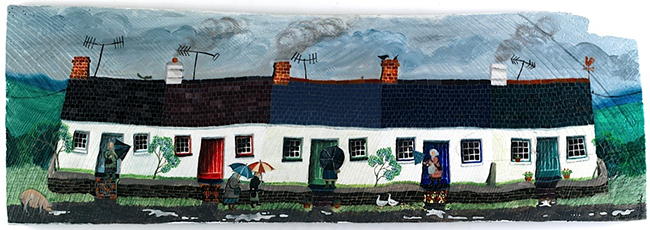

Shoreham

Discuss both the sea and colour in your work?

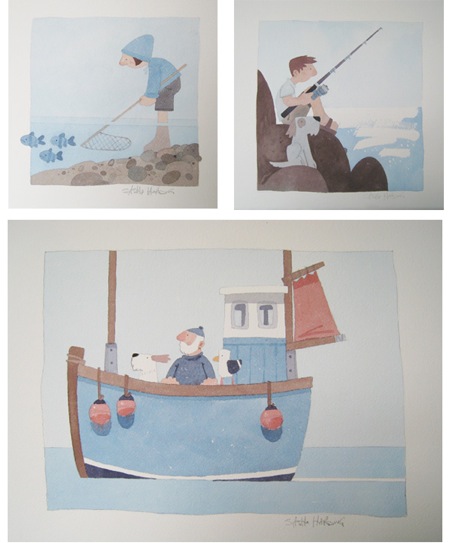

I am quite well known for my use of colour. I use very high quality oils with a high pigment ratio which I think is important to make my colours ‘sing’. Occassionally I treat myself to a certain blue which is prohibitively expensive but it looks incredible. My obsession with the sea began whilst studying at Rotterdam Art Academy. My studio overlooked the harbour and I became fascinated by the shapes and colours of the boats.

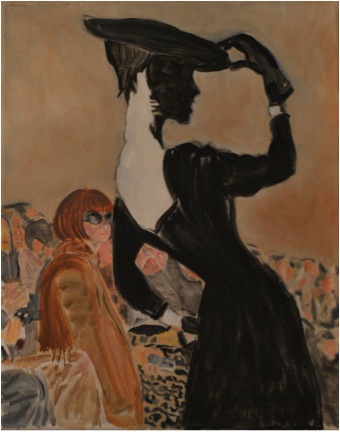

Boats1

You work from, “Quick sketches”. Can you discuss the stages your work takes?

My sketches have become quicker since having children as they don’t let me sit still for long! However, the speed of the sketches mean that the lines are fluid and not overworked which I hope carries through onto my paintings.

You exhibit around the world, both solo and group shows. Can you expand on how this had developed over the past 20 years?

I began by doing all the big art fairs in London, selling the work myself until I got picked up by several agents and galleries who offered me exhibitions and gallery led art fairs in London / Dubai / Paris and New York. I’ve always worked very hard and it took a lot of perseverance in the early days to get my paintings out there.

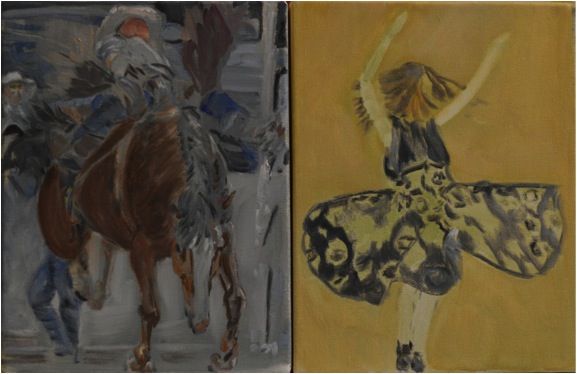

The Wheel

How important has the internet become for your artistic career?

The internet has brought a whole new audience. I now have customers across the world seeing a painting on my website and having it shipped out across the globe. In fact I have quite a few customers in Melbourne who have done just that!

You have done several commissions in particular for P&O Cruises, can you expand on this?

This was really fun as the paintings were huge. There were lots of very specific guidelines though for example everything had to be certifiably fireproofed so I couldn’t paint on board as normal, I had to paint on a special canvas that is used in theatre set building!

How important is commission work to your career?

It is an essential part of my career but it can be quite nerve racking when you bring the client in for ‘the big reveal’! Thank goodness I have never yet had someone who didn’t love what I’d done but it can be terrifying!

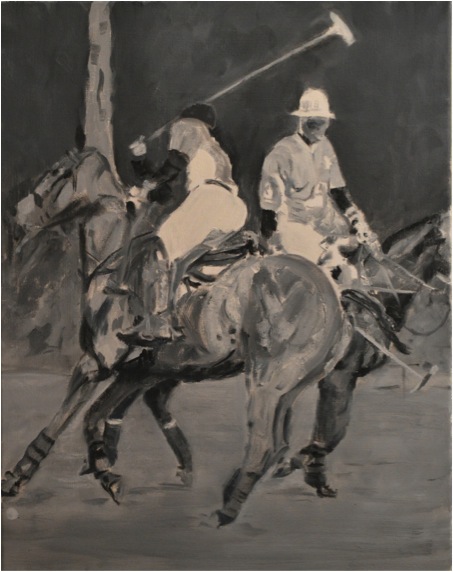

Commission Piece

Discuss your thoughts on the importance of art in hospitals?

I spent some time in hospital a few years ago when my baby son needed heart surgery. It’s a difficult time for parents and so if in any way I can help make the time pass more easily, I am happy to do that. I remember once going to meet a consultant and the room looked dreadful with a half torn Mickey Mouse poster on the walls. It shouldn’t have been important but it did make me worry about the standard of the place.

You also present your work in the form of prints. Please discuss?

My paintings are not for everyone’s budget so I am glad to be able to offer a cheaper option if someone really likes my work. I do both signed Giclee prints and also limited edition handmade silk screen prints.

When did you first start using this medium?

I trained as a print maker at university.

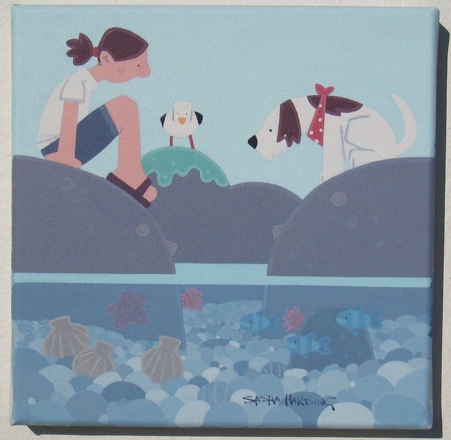

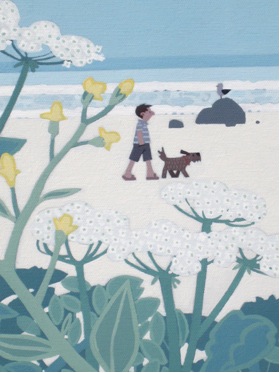

Seagulls On The Rock

How do you decide which works become prints?

I choose the most popular paintings to turn into giclee prints. With screen prints it is completely different though. There is no original – The print is the original in its own right. It isn’t a copy of a painting.

How many do you have printed per Edition?

The screen prints have a maximum of around 75.

Norfolk

Can you discuss your involvement in the Two Kats and a Cow Gallery?

I set up Two Kats and a cow Gallery in 2001 with friends and fellow painters Katty McMurray and John Marshall. We’d all been painting on the seafront for a few years but felt like Brighton was lacking a good contemporary art gallery. We completely renovated it ourselves and built it up to be what is now a major gallery in the South and a popular venue on the Brighton Tourist trail.

Brighton Pier

Can you discuss your work, ‘Mevagissey Morning’?

Mevagissey morning was painted this year and sold almost as soon as I hung it. It all came together really well. Sometimes a painting just flows and everything worked with this one from the word go.

It is quite a large painting; 90 x 90 cm plus frame. Its oil on board.

I’m a huge fan of both Cornwall and the Cornish artists of the 2oth century. In particular the St Ives Group – Peter Lanyon, Roger Hilton, Alfred Wallis.

Mevagissey Morning

In you 2014 Collection you have work from the Souk. Can you discuss both the place and the inspiration it has given you?

Entrance to the Souk

I took my boyfriend to Marakesh as a surprise 40th birthday present. He ended up suprising me by proposing to me whilst we were there so this painting has lovely memories for me. Morocco is so inspiring. The souks especially are such an explosion of colours – it’s a painting paradise.

The Hat Shop in the Souk

Contact details.

www.kathrynmatthewsartist.co.uk

www.twokatsandacow.com

Kathryn Matthews, Shoreham-by-Sea, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September, 2014

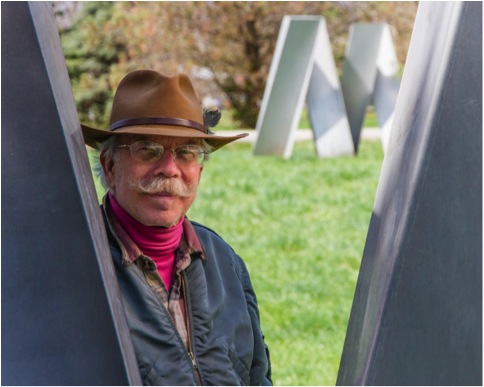

Jon Barlow Hudson

Can you discuss your thoughts on where and with whom the “Behind the Scenes’ drawings etc. for a public art piece are stored for prosperity?

This is a very broad question and one I cannot really answer as I am sure that of the hundreds of public art entities deal with such things in different ways. Sometimes they might want the drawings or whatever that lead up to their piece to be part of their documentation of a project and others might not care at all. An unusual example is that I not long ago donated all my structural engineering papers and others to the Queensland State Library in Brisbane relative to my two major sculpture projects for the World Expo 1988, held in Brisbane. The Minister for the Arts Ian Walker received the donation into the library. Following that I offered the stainless steel sectional maquettes of the 100 foot high sculpture PARADIGM, to them also, to fill out their Expo collection. Often such items and donation might simply go the relevant public art committee.

Discuss your thoughts on world exposure to your sculptures career?

I attribute my work as an artist to having grown up traveling and living around the world from a very early age. All that I have seen, experienced and done, overseas in particular, has made me the unique person and the artist that I am: without which I would be a totally different person. The shape and meaning of my sculptures is the fruit of this experience. My first large--scale public sculpture project overseas was the commission of two very large scale stainless steel sculptures for World Expo 1988 in Brisbane, Australia. Following that project, I continued to receive commissions for projects in, 27 different countries. If I could say that one project led specifically to another, I would. I can only surmise that each and all of these overseas projects and international and intercultural experiences has contributed in one way or another to ‘My life, my sculpture and to my career’. Back in ’86 when I first made contact with Expo, to my perception there was not much attention to overseas projects by national artists. Given my life experience, it made eminent sense to focus outward and pursue overseas projects since my sculpture and my aesthetic sensibility is based upon universals and the timelessness of art and creativity, I was charged with expanding around the world with my sculpture. This has in turn immeasurably enriched my life not just by the experiences, but through the friendships and personal contacts that I have encountered throughout these overseas adventures. I probably know more international artists and friends than I do State—side, all of whom have made some contribution to my life and career.

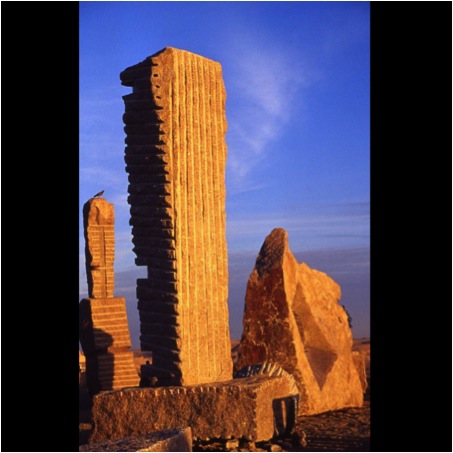

ASWAN SYNCHRONICITY & TS’UNG TUBES

2001, 2002, Aswan granite. Aswan International Sculpture Park, Aswan, Egypt

How important was your time with Charles Ginnever in Vermont to your later professional life as a sculptor?

I greatly value the year with Ginnever both for his friendship and for the experience of being around a professional “New York” sculptor whose friends and colleagues were/are DeSuvero, Chamberlin, Kaprow, Forakis, Downsberry, Weiner and others. I helped make his large scale steel sculptures and helped with his exhibits, such as with the Louis Kahn maquettes and his sculpture models. It provided a creative, adventurous environment in which to explore and develop my own sculptural ideas.

Towards the end of the year, his friends Allan Kaprow and Paul Brach, among others, were helping form the California Institute of the Arts in LA, which led to my attending Cal Arts for its first two years, resulting in my BFA and MFA in 1972. Had I stayed in my home town working in my studio, or returned to Germany or elsewhere, my life would have been totally different. My time with Ginnever let to Cal Arts, which led to the 2 years working at a gold mine in northern California, then to New Mexico and on. He lives in my mind as a quintessential American sculptor, making wonderful sculpture, on a par with his contemporaries.

DANTE’S RIG, Chuck Ginnever

Aluminium, steel & cables. About 3 m. hi.X 4 m. L. x 2 m. wide. c 1966 aprox.

Discuss how your art has been influenced by your travels?

My first five years were on the plains of Wyoming. The American First Nations peoples say that these years are a time that is very important in one's formation, so they ask about your upbringing during these years. Following this we moved east, then about a year later we continued on east to the deserts of Saudi Arabia for three years: still formative years. My world travels began then and continue today. That early experience in the Mid East and other places between here and there, exposure to ancient stone architectures and distinctive, impressive natural environments, have been a constant inspiration in my being, my relation to the natural environment of the world, to previous cultures and creative products of both ancient and contemporary times---and of the sculpture I make today. As a kid, to climb around Baalbek, Petra, Jerash, Rome, Machu Pichu, puts one in touch with earlier peoples---one receives a communication from them. While I began my public art "career" working with stainless steel, a rather contemporary material, I tend to prefer working with stone: both as a way to work with nature, but also to do as the makers of Baalbek did, and speak to peoples down thru time into the future.

You have a strong background in the fine arts. Discuss your thoughts on how an academic background supports an artist

Creativity takes as many forms as there are artists. Each artist must follow and create their own path. For some it may be as an independent, “folk” or “non-academic” artist, as an artist nevertheless. Such folks often have a strong sense of discipline and vision, so are easily at work rather than not. My lot was to grow up going to school, then on to college, transferring to the Dayton Art Institute, then Stuttgart Art Academy, Ginnever’s farm studio, finally Cal Arts, eventually teaching art at university. My trajectory was academically based. It provided me with a broad education and experience in making art in a wide variety of media and a broad study of the history of the various arts. My intention was to teach art, and for that the academic foundation is necessary. Interest changed and I focused on making sculpture as an independent artist. However, I consider that a broad education is important in teaching critical thinking, an open and inquiring mind and providing useful training and discipline for whatever creative endeavour one might choose.

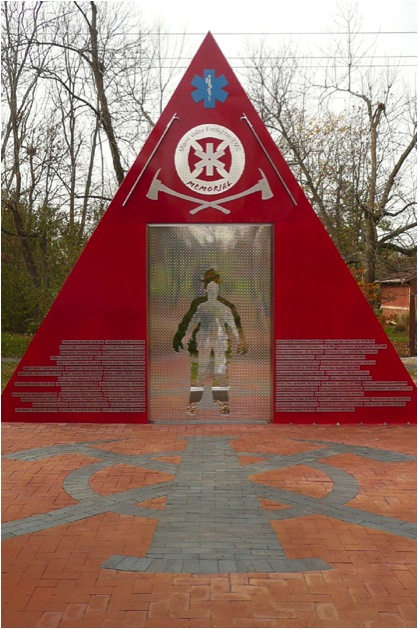

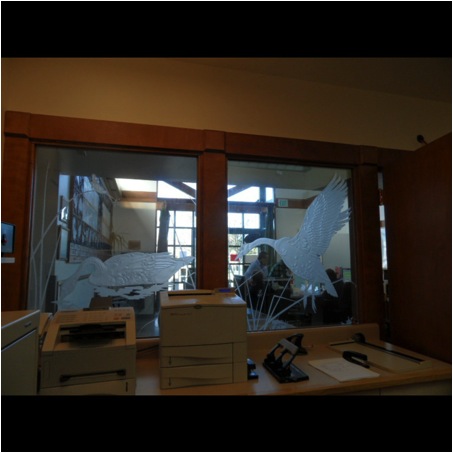

Can you discuss the commission of ‘FIREWALL?

A state-wide competition was set up calling for a firefighter memorial for this country region. My past work got me chosen to make a proposal, which was the one selected.

FIREWALL

c 2010, Steel powder coated, stainless steel, aluminium, brick, 5 meters high x 15 m. x 15m. Miami Valley Firefighter/EMS Memorial

FIREWALL was commissioned to be a memorial for fallen firefighters and emergency medical service people. I wanted to create something that was an obvious reference to firefighting and that was different from other such memorials. I also wanted to create something that was an outdoor environmental work that created a special and sacred space for memorial services to take place. The triangular shapes were arrived at in order to symbolize fires, and of course the colour red. There are numerous firefighting symbols within the work, along with a silhouette of a firefighter. This was inspired by a Jain icon of the Buddha—the figure being empty space. The brick precinct within which the three triangles are installed includes the firefighting symbol of the axe and hose nozzle.

The memorial is installed in a natural park setting with a path made of cobble-stones from an old fire station. As one approaches the memorial down the pathway, one will see the three fires/triangles, then the silhouette of the fallen firefighter cut out in the bright aluminium diamond--plate in the centre of the large triangle—which material is found in the middle of many fire trucks. Then as one enters the precinct, one is surrounded by the three fires—much like the experience of the firefighter performing their duties.

On both sides of the silhouette are attached the names of currently 68 fallen firefighters & EMS personnel. The sculpture is 5 m. hi. The largest triangle and the three of them are installed on a brick precinct 15 m. on a side. The triangles are made of welded steel powder-coated red, with parts in aluminium, stainless steel and brass. It is installed in Stubbs Memorial Park, Centerville, OH, USA, 2010.

‘Double Helix’ is a mathematical piece and it is also viewed daily by professional mathematicians. Can you discuss this?

HELIX was commissioned for the Wright State University Diggs Life Science Laboratory in an Ohio state percent for art project 2008. Their theme was the bio-sciences, as well as mathematics and geometry, given that the math building was next door and some of their funds were involved. After much thought and research into these disciplines, I arrived at the idea of a double helix constructed of dodecahedra, which are Platonic solids constructed of 12 pentagonal shapes. They are welded together, with the welds ground down and away, so that the geometry remains clean and clear. They are assembled in the configuration of two helix which intertwine but do not touch. They are large enough for people to walk through them and sit on them. This project was designed in relation to the environment of the bioscience building courtyard and other surrounding buildings.

The sculpture is constructed of welded stainless steel with sanded surfaces, each pentagon being unique and is installed on a berm of grass covered earth with a black brick surface just under the sculpture. It is 2.6m. hi. X 2.6m. w. x 8 m. Long.

As the viewer walks around HELIX they will see how the two helixes intertwine and rotate in a flow of geometric form. The many different surfaces reflect the light in many different angles so the light and colour is multifaceted. Most double helix sculptures look more like the DNA molecular structure, whereas this one is more abstract, the two helixes are not connected together and the use of dodecahedra is not normally associated with DNA double helixes. As the viewer walks through the canter of HELIX they will be surrounded by dodecahedra, as if in the world of geometry.

I have not had feedback as to specifically what mathematicians think about it, but what I have heard has been positive. When I was installing it, one of the bio science professors came out and screamed for the installation to stop, because the vortex was turning in the “wrong” direction. I was later told that DNA helix turn in both directions: Z-DNA. In any case, this is poetry and not an engineering or scientific model.

DOUBLE HELIX

c 2008, stainless steel, 3 m. hi. x 3m d. x 8 m. long. Ohio Arts Council Public Art Project, Diggs Life Science Lab., Wright State University, Datyon, OH

PARADIGM is also mathematical. Explain this work within a mathematical context.

PARADIGM is the sculptural expression of the DNA molecular structure, the double helix being the notable feature—here indicated by the spiralling pattern of the tube forms emanating from the body of the sculpture. The other important meaning of the sculpture is that it is the “axis mundi”—world axis, the metaphorical axis around which the world turns, the “still point of the turning world”, which is Brisbane during Expo.

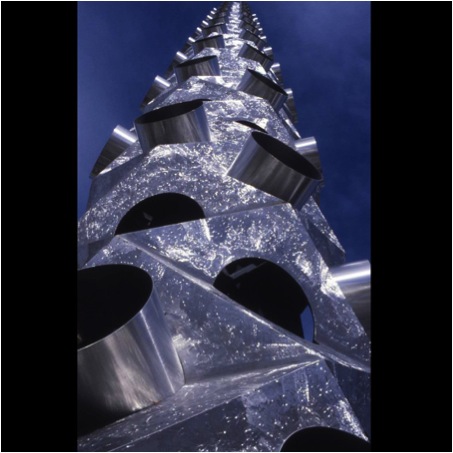

PARADIGM Detail

A paradigm is a pattern, example, or model, for example, of a particular world view during a certain time period. In my vision, the oscillating/spiralling aspect of this sculpture represents the changing, flowing, cycling of various aspects of the world along the continuum of existence. There is a pattern to events on the macro-cosmic perspective, more difficult of vision on the micro-cosmic level. On a rather micro-cosmic level the monocoque structural form and pattern of the sculpture is very reminiscent indeed of a “cholla” cactus “skeleton” from the Arizona desert, where I lived for a year. Even though it is a very geometric form it is nevertheless a very organic form in its essence.

Speaking of skeletons, another reference that PARADIGM indicates is that of the vertebral column, which, while practicing Tai Chi or other martial arts, must always be very straight so that the energy may flow freely. Thus PARADIGM is a “vertebral column” between the earth and heaven thru which the energy of the universe flows. I think of PARADIGM as representing another aspect of existence—that each segment represents the conscious awareness of each present moment of being on the continuum of the progression of time, extending up into infinite space and time. The segments are designed with both yin and yang aspects to their form -- the protruding cylinders and the round openings to the interior. This later aspect leads to yet another realm of meaning, inspired by the ancient Neolithic Chinese jade ritual objects called a “cong” or “ts’ung tube”, symbols of the unity of heaven and earth. They are generally square forms, often segmented horizontally, with a round, tubular space drilled through the entire stone: the square representing earth, the round space heaven. These are wonderfully intriguing and archetypal artifacts.

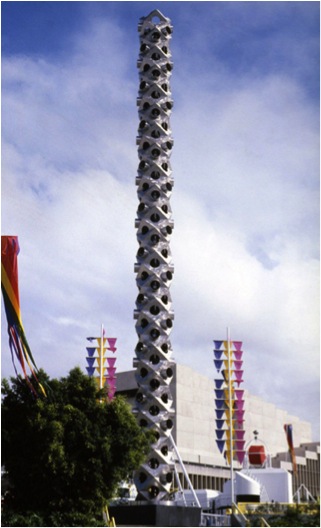

PARADIGM is 100 feet high by 8 feet diameter and about 42,000 #’s in weight. It is constructed of type 304 stainless steel—the body of the piece is built with 5/16” thick plate and the tubes are 1/8”. The interior structural elements are all of mild steel, painted with a heavy coat of PFI PF300 Savinite epoxy primer, a high-zinc paint developed for Rockwell International airplanes. The sculpture is built in 7 sections which are bolted together: I believe they are numbered in sequence, which is important due to the structural specs on each successive unit. It was engineered for 110 mph as requested by Expo 88. It has been in storage since Expo, for most of the time under a bridge nearby the river in Brisbane. It was moved to an interior space in advance of my arrival in Brisbane, in 2014, to inspect it and to further the reinstallation of PARADIGM in Brisbane. This is an ongoing challenge. Its companion Expo sculpture, MORNING STAR II, a 15 foot diameter mirror polished stainless steel geometric “diamond” or “star”, was after Expo reinstalled in the Brisbane Botanical Gardens close by the Parliament Gate. A sectional stainless steel maquette of PARADIGM has been offered to the Queensland State Library and was accepted, but awaits shipping. I have been lobbying anyone in government and otherwise regarding its reinstallation since the end of expo, most often the Lord Mayor. The current Lord Mayor has indicated his support for the reinstallation, but discusses the need for a suitable context and funding. As a result of not altogether proper storage, it now will require a bit of maintenance.

A wonderful gentleman in Brisbane, who has become a good friend, Mr. Peter Rasey, has been very energetic in promoting the reinstallation of PARADIGM. He is a committee member of the Lord Mayor’s Parks Advisory board and an advisor to the Lord Mayor and others, on special interests regarding tourist projects for Brisbane and the G20. So the fate of a powerful, meaningful, beautiful, landmark sculpture the equal of any other one cares to stand next to it, is still at risk.

PARADIGM

c 1988, stainless steel & 66 airplane lights. 30 meters high x 2.6 m. dia.

Commissions for overseas must present logistic problems. Can you explain one or two of them?

For PARADIGM and MORNING STAR, I had to pre plan their construction taking into consideration the size limit for over—road transport, railroad and sea transport and the size of the steel land—sea shipping containers. MORNING STAR had to have a wooden crate built around it once it was about 80 % complete, not over 12 feet high, so it could go as one unit. PARADIGM had to be designed into 7 sections, so that they could all fit within the shipping container, both length--wise and width—wise. Since it would be constructed in seven sections, over a five month period and had to be constructed horizontally, it was never fully assembled prior to its Expo installation—it stood as straight as an arrow! The shipping had to be coordinated thru a state—side shipping agent and in cooperation with Expo. Once on site, I worked with two New Zealanders to complete MORNING STAR.

Another logistic experience was the commission, thru an architect in Hong Kong, for three large scale sculptures for a project in Jakarta in 1992. Once I had the sculptures completed, in order to ensure payment to me, and for the client to be assured that what they were paying for was indeed three sculptures, I had to have an SGF inspector, as part of the VCS (voluntary control system) come and inspect the sculptures at the fabrication facility, as to their voracity as sculptures conforming to what was ordered by the client in Jakarta. Once that was satisfactorily completed, arrangements were made with the shipping broker to truck the three large crates to the port for sea shipping. Upon their arrival in Jakarta, and damage to one of the sculptures, I spent a couple of weeks on site overseeing repairs of the sculpture and construction of the foundations, along with a stout case of Lord Ganesh’s revenge.

EIDOLA II

c 1992, mirror polished stainless steel, 4 meters high. Mulia Tower, Jakarta

Atrium sculptures must need different design techniques. Discuss one of your atrium pieces and the importance of the positioning in relation to the viewers.

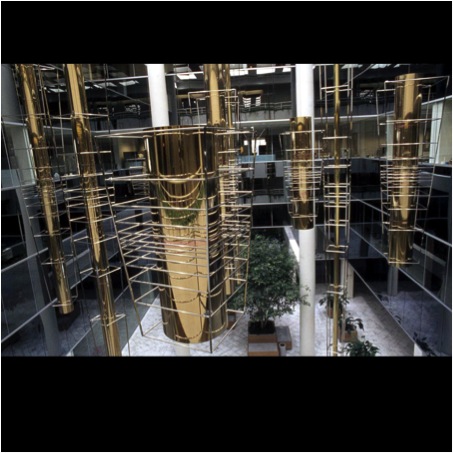

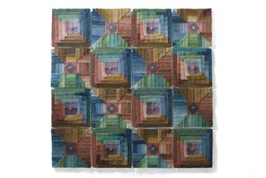

The atrium installation TS’UNG MUSIC was designed for the four story atrium of the Emery Northlake office building just north of Cincinnati. The distinguishing characteristics of the space were the three glass walls surrounding the atrium, with all their mullions and the fourth wall was elevator balconies. On the wall opposite it, were two floor—to--ceiling columns and the ceiling contained a square grid of 25 square skylights, 5 to a row. I was charged by the architect to design a sculpture to work with the given environment of the atrium, so on one hand I had the round columns, on another the windows with all their mullions—lots of horizontal lines and vertical as well. I began working with a rough cage concept and I had the column shape to think about as well. Serendipitously I happened upon an Asian Arts magazine and on the cover was a photo of the Neolithic jade “cong”, or “ts’ung tubes” from ancient China. The author, Lars Berglund, explained that the jade ritual objects represented the unity of heaven and earth: the square outer form being earth, yin, and the round space boring through the square from end to end, is heaven, yang. On the outside surfaces of the square form are often found some vertical motifs and many horizontal incisions. Upon seeing these jade objects, it immediately brought my cage and my column forms together, the latter inside the former. Additionally, the concept of the unity of heaven and earth seemed appropriate for a sculpture suspended in space within a building.

TS’UNG MUSIC

c 1986, photos JBH. Stainless steel & brass. 9 units, from 3’hi x 3’dia. To 27’hi. x 3” dia. Installed originally in Emery Industries/National Distillery Corp., Cincinnati, OH.

Once I had the basic form, what to do next? In looking at the space and how one is to suspend an atrium sculpture, one has to attach it to the ceiling. Given that there are 25 skylights, how to relate to them? What logic to work with? Perhaps in studying the ts’ung tubes, there I think was some mention of the magic square of alchemy and how that relates to the plan of the ts’ung tubes. There are 9 numbers in the square, from 1 to 9: even number in the corners, five in the centre and odd numbers on the sides. This set of numbers fits into the skylight grid of 25 in a diamond plan. So I then had 9 skylights from which to hang nine elements. (Far too many for the budget!) So if the number one position is the skylight for number one element, how to distinguish each from the other 9 elements? Thus 1 became 3 feet high by 3 feet diameter with each number progressing longer by 3 feet and each number progressing smaller in diameter by 3 inches, making number 9 the longest and thinnest. Then how to place them?

The cage design allowed me to utilize the Fibonacci numerical series in the spacing between the horizontal bars, but rather than start at one end, I started in the centre of each element, going both up and down, which allowed for them all to be placed within the space with the centre of each on the same plane, which was I think around the third floor more or less. They had to be high enough above the ground floor pedestrians yet not too high within the atrium. Thus each floor had a unique perspective on the installation.

New owners took over the property in 2008 and for some reason wanted a different “décor” so had the sculpture removed and destroyed, without contacting me or anything of that nature. This was my second Cincinnati atrium sculpture that was destroyed by the Taliban.

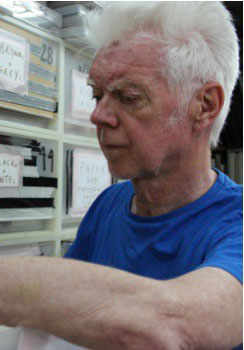

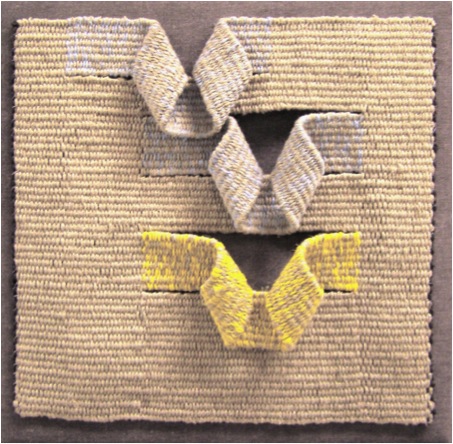

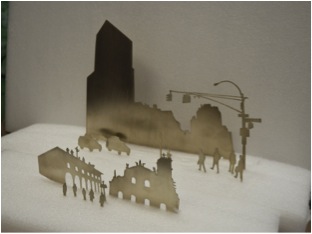

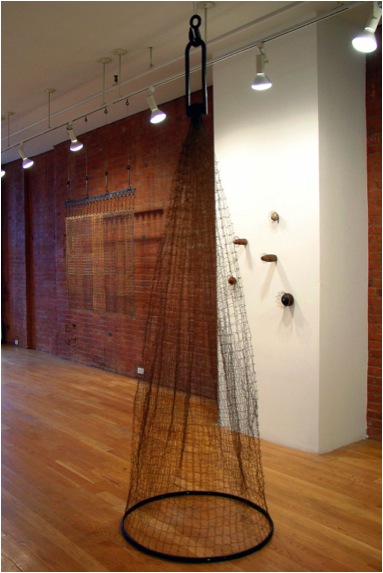

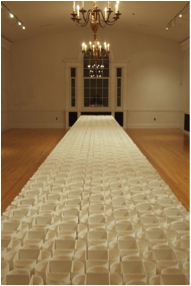

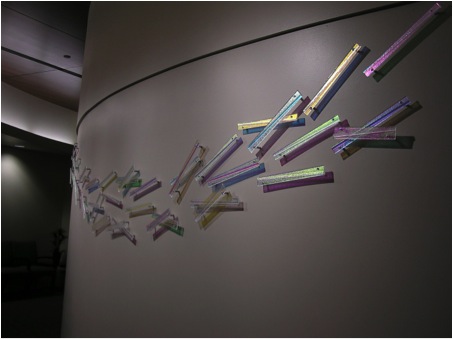

Your installations are not always metal. Explain you installation 'Felt Hat Body Install' and relationship of the work to you wife and creative partner, Debbie Brush Henderson PhD?

My wife decided to go for a PhD. in costume history, with a focus on the history of the man’s hat, an area not previously studied. We travelled the country interviewing hat makers and sellers and visiting the few remaining felt hat making factories; in the UK and France as well. The steps of making felt hats are pretty much as they have been for a few hundred years, since “modern” machinery has been involved. The initial steps in forming the felt hat is a machine the blows the fur fibres along a tube, then into a space within which the air is circulated, carrying the fibres, round about a metal cone shape about 30 inches high or so, with holes in it so that the vacuum below it will pull in the circulating air carrying the fibres, which will then build up on the surface of the cone. This is done for a specified length of time to get the required thickness of fibres built up on the cone. It is then removed from the space, dipped in hot water, the felt hat body is then slipped off the cone and folded into a flat cone shape, rolled in a cloth dipped in cold water, beat about a bit, dipped in hot water, beat about a bit, for a few sequences, then moved on to the next steps. Down the line it has been pretty well “felted” together and also died a colour in many cases, so it is then fit over a machine that with steam will form the felt hat body into its first iteration in a hat shape. These are then inspected for potential imperfections and those that don’t pass are set aside and disposed of.

At a factory making such hats, I was provided with about a hundred of these felt hat bodies that did not pass inspection, with which to make a sculptural installation. While there are countless ways to assemble such shapes, I really like the cone shape and that, since it is the fundamental birth formation of the felt hat, and the hat is itself a sort of cone shape—the earliest hats were just that—it seemed to me a reasonable logic with which to assemble the felt hat bodies into a sculptural installation. The hats create a cone texture on the overall shape of the cone structure of their assembly. I chose the hanging cables in deference to the elliptical cable arches which Antonio Gaudi utilized in some of the construction of his great church, the Sagrada Familia.

Debbie chose a topic that we could do together, allowing us to travel widely in search of hats, hat makers, hat factories and the concomitant history. The project resulted in a museum exhibit, as I write this we go tomorrow to take down the 8th museum venue. Debbie also wrote four published books on the subject. We grew to be totally enthralled by the subject and its people and history. I even developed my own collection of hats to wear.

I would like to do more, but I also have a thing about making sculpture out of more permanent materials, like granite. While Debbie does not help with the making of the sculptures, she is my design partner.

FELT HAT INSTALLATION

c 2007, 90 felt hat bodies and nylon lines, about 2 m. dia. X 3 m. hi.

You have work in 27 countries. How do you keep track of everything?

Sculptures are not sacrosanct. They get both taken good care of and not, sometimes vandalized, stolen, destroyed, pushed aside. Just the other day I went with this same friend to see one of my 1985 sculptures in the basement of the bldg. where it was originally installed, for a moved away corp. Thankfully it has been saved, but needs to have the clear lacquer removed, to be repolished and recoated.

Many of the overseas projects are just too far away to hope to deal with, and pertinent individuals that might have something to do with them are either long gone or out of touch. Occasionally, if I am lucky, I might hear from someone regarding a sculpture someplace. Of the two Expo sculptures, MORNING STAR is safe in the Botanical Gardens, though needs wash. PARADIGM, while now in a more secure and weather resistant storage facility rather than under a bridge, is still at risk. The Lord Mayor of Brisbane has indicated his interest in seeing it reinstalled, but how it gets paid for and what context within which to place it has yet to be determined. I have lobbied everyone I could find in Queensland since Expo to get PARADIGM reinstalled. Even seeing it in a dark storage building, laying unassembled in its individual sections, it is still a powerful and impressive sculpture. A great loss to the community not to be reaping the value of it installed.

FIRE IN THE HOLE!

c1986, mirror polished stainless steel. 4 m. dia., Civic Centre Plaza, Omaha, NE

Do you feel that public art is dependent on the mood of the public or the financial directors?

The public is certainly involved, both as viewer and as tax payers and voters. Most projects tend to become accepted, but occasionally something is not and that can sometimes lead to its removal. The Tilted Arc wall sculpture in the courthouse park in New York City by Richard Serra being a notable example. The public is also part of the public art process as public art committee members, supporters, funders and the like.

They come and go, the type of art that is supported can also change. Today, as the use of computers increases in various aspects of design and construction, there seems to be quite a bit more works that are very much computer derived.

As for the financial directors, one would have to define who they are: whether public art committee members, city officials, community philanthropists, federal government officials or whomever.

Take one of your sculptures that you feel has a strong emotional effect on the viewer and why you think it has?

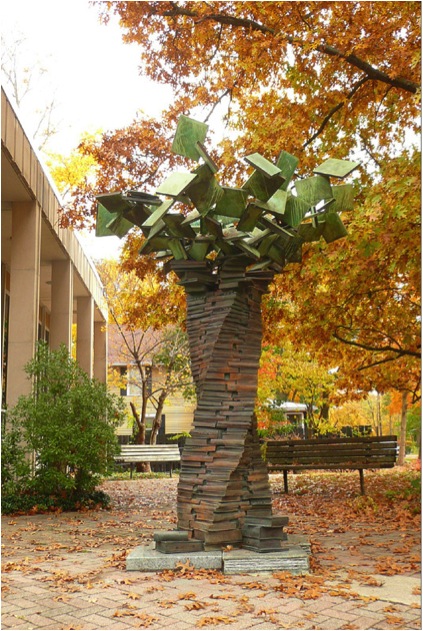

Probably the most comments I have received back, since the sculpture is in my home town, is for TREE OF KNOWLEDGE. Several community members thought we ought to have one of my sculptures here in town, since the rest of the world was getting them, so they set about raising funds and setting up the project. Once the commensurate funds were available, I set about making the mock-up.

TREE OF KNOWLEDGE

c 1992, bronze, 3.6 m. hi. x 2.6 m. dia.

Public Library, Yellow Springs, OH. Plan grant from the Ohio Arts Council

In order for the project to develop, I worked up a proposal for them and for fundraising. In thinking about the town, we already have a “yellow spring” iron orange, which has been in use since the First Americans were here. The stone work around the spring was built up into a recognizable form in the early 50’s. In wondering how to represent the village in all its qualities, I got to thinking about the character and history of the village, I noted that we have had educational institutions here since the beginning, Antioch College was founded here in the 1850’s, there was also Antioch Publishing, Antioch Grade School, and history of educational experimentation, many writers, educators, artists, scientists and engineers, due to nearby Wright Patt AFB.

The common element of all these folks is books and book learning and the other characteristic about the village is its trees: we have the 1000 acre Glen Helen from the College, Bryan and Clifton State Parks, a serious Green Space program around the village and a dedicated Tree Committee, thus the tree became a likely contender for significant signifier. The first tree form I made, using book shapes, was just branches; it was too much like a dead tree. Then I was driving along in my car thinking about it and the tornado from the Wizard of Oz came to my mind’s eye and that provided the logic for constructing a tree of books. Since a tornado is a vortex, and one often sees large trees with a vortex structure to them, the vortex became the operative motif. I designed the trunk to be constructed of books in a helical plan and at the top, books continue spiralling out from the trunk to become the foliage, thus a moving tree form of books.

The vortex is found throughout nature, from the micro- to the macrocosm and is very indicative of life. The trunk of the tree is made from real books – real books were stacked up in the helical form then a latex mould made of it, then eventually cast in bronze. The foliage books were fabricated from sheet bronze, then welded into place. In the foliage area there is a “tree house” and also a “book plate” – Antioch Publishing used to print book—plates. On the trunk there is a “book worm”, with glasses, and various other items, like tape recorders and cassettes, some of the books were leather bound with great textures, I did not have a computer to include, so the tree is rather engaging for those willing to take time to explore. I just asked poet Amanda Williamsen to describe why the tree works so well.

“The books appear to take flight like birds: it is a celebration of books that come alive from the ground up, that anyone, regardless of art education, can easily perceive: it shows that learning is not static but growing: the roots of the tree – books which cover the actual hold down bolts – are not stodgy: the tree has motion in all its parts.”

What more can I say………..

Space. The space that a work will fit into must have a huge influence on the work you produce. Can you expand on this?

Some of my earliest works were found tree constructions in the nearby Glen Helen forest – form and space. Of course my early small scale sculptures were/are more about space and form as sculptures, often enough implied expansion beyond the confines of their material forms. As I grew into making large scale sculptures and finding ways to get them funded, that meant working in a wide variety of architectural, environmental and cultural situations. This in turn meant the question of how to integrate the sculpture into that particular project context. How to relate the sculpture to the forms, spaces, colours, textures, uses of the spaces, both interior, exterior and surface, and the broader cultural contexture. Such spaces can be a wall surface, atrium space, interior or exterior ground surface, natural setting, and street scape, each one of which requires different relationships to gravity and to affixing the work to whichever surface will be doing the support work. I am always working with gravity, whether consciously or not, secondly, structure, which is basically about gravity in any case, to the functional situation, the material with which to make the work, relative to all of the above, or some other aspect altogether. I think all of the above pretty much holds true whether you are working with stone, steel, lights, fabric, glass, water, plants, whatever. I have particularly enjoyed the challenges of creating sculptures that relate to many different spaces.

SHIVA : SHIWANA

c 1980, stainless steel, 5 meters dia., HQ of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory – Very Large Array, on the Plains of San Augustine, west of Socorro, NM.

One project I particularly enjoyed was for the National Radio Astronomy Observatory – Very Large Array, west of Socorro, NM. Given that it is what it is and listening to outer space, I wanted to include outer space in my sculpture, as well as the location on the ground. The telescopes are moved around on three rail road tracks, in a Y configuration. The telescopes are listening to objects in outer space, many of which are more or less “round” or symmetrical, as are a number of manmade objects orbiting the earth. Thus I came to the tetrahedral structure as one that could, first, reflect the Y configuration of the site rail tracks that could represent “spherical” bodies orbiting earth and also the celestial orbs filling outer space which the telescopes were listening to. My sculpture, SHIVA : SHIWANA, is fairly liner in format, which allows the three outstretched “wings” to reach into outer space. Though standing on one leg, like Shiva, it is totally symmetrical, it could easily be one of those objects floating freely in space. Within the ends of the wings, are shapes that utilized on buoy radar reflectors, which reflect the radar signal back to the sender of the signal, the sculpture is a listener to outer space just like the telescopes.

The name Shiwana, comes from the local Native American Tewa tribe, if I recall correctly, which is used to designate a healer that has received his powers from being struck by lightning. We have references to space both ancient and modern.

Discuss your thoughts of the importance of public art in public spaces? What would you like the public to gain form the experience?

Given the history of art and that it has been so much a part of virtually every culture since recorded time, within their public aspects as well as more private, it is pretty self-evident that it plays an important role in every society. It has even been used for negative ends in some cases due to its importance. For me, there is no question, there are always nae sayers and the Taliban who will blow up Buddas and destroy my atrium sculptures and such, and politicians that want to cut funding to the arts, all the studies show the importance of the arts not just to the cultural and social life of society, but to the economic prosperity of society as well. Almost every country round the world today has a sculpture symposia, as just one small example, the results of which contribute to the local communities where they take place.

When I started creating public sculpture in the 70’s in the States, you could count the number of public art programs on two hands – today there are hundreds. Another example is China – in the 70’s they were still doing social realist worker art yet today there are many artists creating wonderful art for public places throughout the country, such as the spectacular works of Ai Wei Wei. Having such a dragon to confront has given him the opportunity to probe the depths and rise to the challenge. He is their Michelangelo.