Lanny Bergner

When do you decide which of your work will be large pieces or installation pieces?

This varies depending on the exhibition venue. Sometimes I will do site-specific installations that are made for a particular space. At times I will do a series of small individual works, but given the opportunity I will turn them into an installation. This began long ago when I first started making suspended mesh works. I found that they could have a singular presence and they could also visually interact with one another. The Perelman installation is a good example of that.

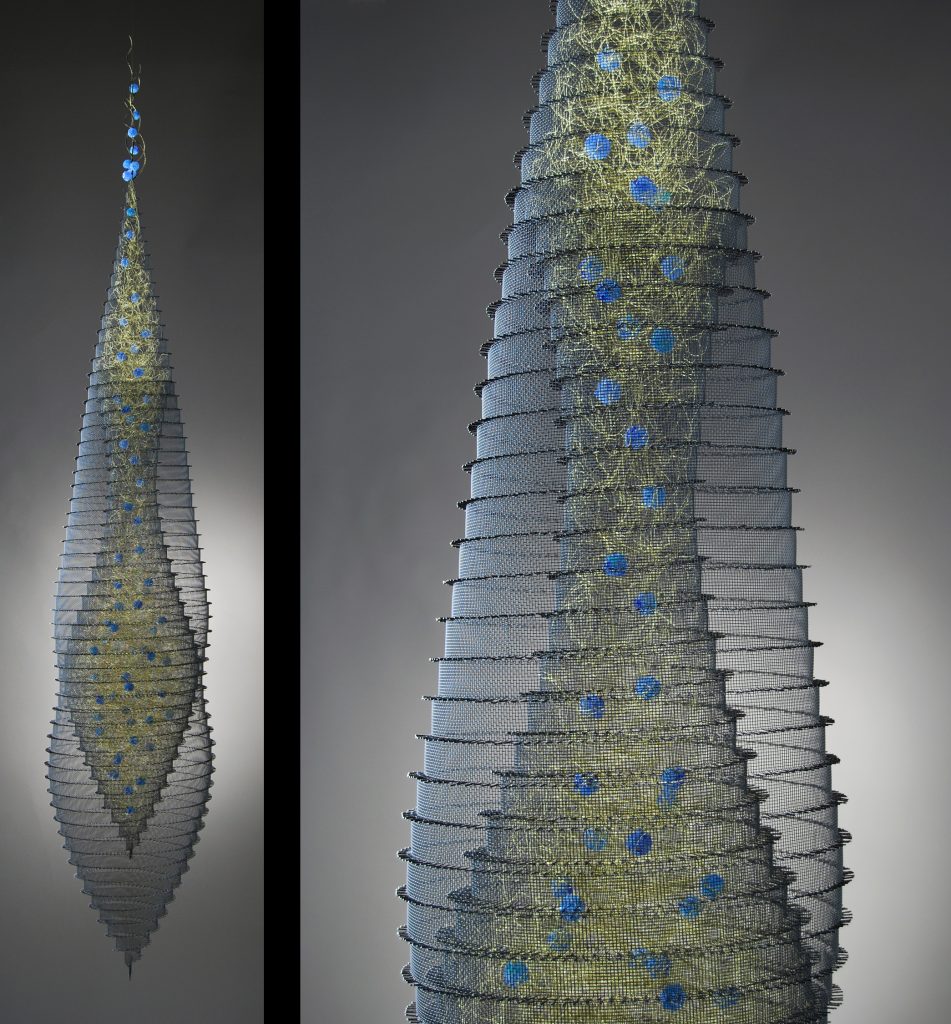

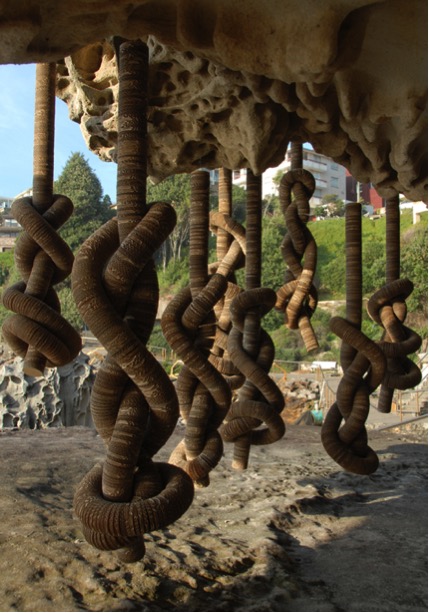

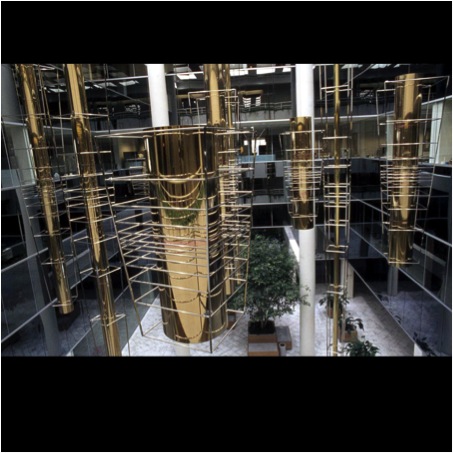

‘Perelman’ –Installation

Can you discuss the work and technique you used in your installation of suspended mesh at the Perelman Centre for advanced medicine?

The seven suspended pieces at the Perelman Centre were made as individual sculptures, but installed as an installation. The Perelman is a healthcare facility so the feeling I wanted the installation to invoke was one of healing and peacefulness.

Twisting the frayed edges of long strips of aluminium, stainless steel and bronze mesh together with flat-nose pliers is how the pieces are made. They are all done in a spiral formation. Some of the pieces have loose frayed brass wire inside and/or vine-like stands of wire and tiny balls of glass frit and silicone. I exhibited some of the Perelman pieces before in an installation I did at SOFA Chicago (Sculptural Objects and Functional Art).

SOFA Chicago Installation: ‘Ground Swell’

You have work represented in Art in Embassies Program discuss the work and where it is?

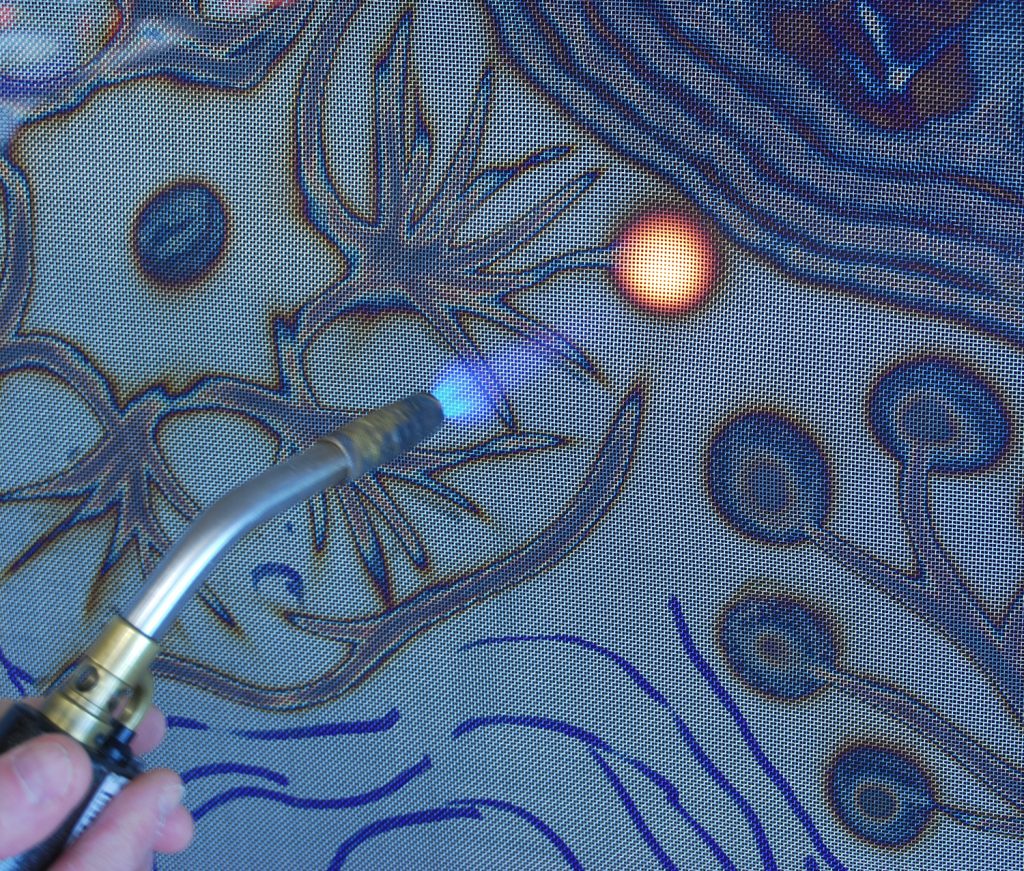

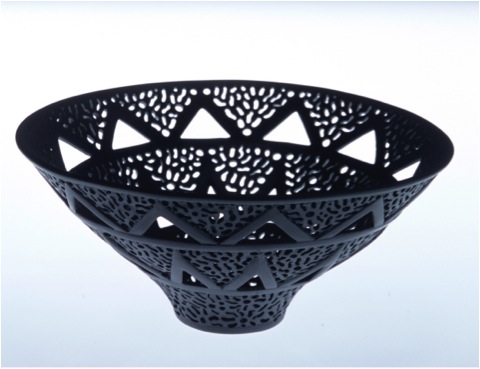

“Primordial Vessel” is the piece being exhibited in the Art in Embassies Program. The painting/drawing on the mesh is created by flame-treating stainless steel mesh with a propane torch. It is being exhibited as part of a basketry exhibition at the US Ambassador’s residence in Tirana, Albania and will remain on view for the three-year term of the Ambassador’s appointment.

‘Primordial’

Can you expand on contemporary basketry and how it is being accepted in the current art world?

It is well accepted in the fibre art and craft world, but to a lesser extent by the “fine art” world. Basketry is pretty much a subgroup in the fibre arts, but it does have its own group of collectors and exhibition venues. There are overlaps of course and many times basketry is shown in broader fibre venues. Basketry has a long ancient tradition behind it and now artists and basket makers are using contemporary materials to create works. I came to the basketry arts by serendipity through sculpture (that is my formal university education) having received a BFA and MFA in sculpture. I believe this has given me a degree of freedom in my approach to basketry and art making. The basketry world has been embracing of artists who push out the boundaries of the medium and explore new approaches. There is much more cross fertilization going on in the art world today with contemporary artist using techniques and materials once confined to the fibre and basketry arts. This intermingling is healthy for all the arts.

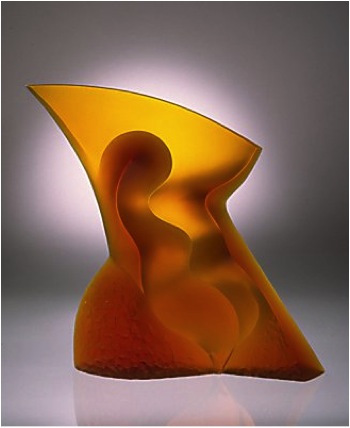

Can you discuss the use of one district colour or colour group in your work?

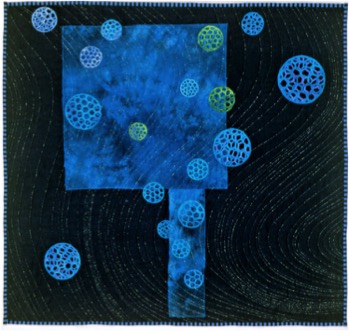

‘Ocean Deep’

Lets take “blue.” This happens to be one of my favourite colours and as it turns out, blue is one of the two main colours I can create while torch treating stainless steel mesh. The other is light to dark amber with the dark end almost a burgundy. So, these colours by default have become the main palette for the “flame painted” imagery on the mesh.

Flame painting

Explain the materials you use and how modern materials continue to fascinate and become part of your current work?

My primary material is metal mesh. I started out using common aluminium insect screening that I could buy at a hardware store. Now, I primarily work with stainless steel mesh. Stainless steel mesh is much more versatile for me because it comes in so many different gage and grid spacing types. This means I can work on a larger scale and create different types of forms depending on the mesh I selected.

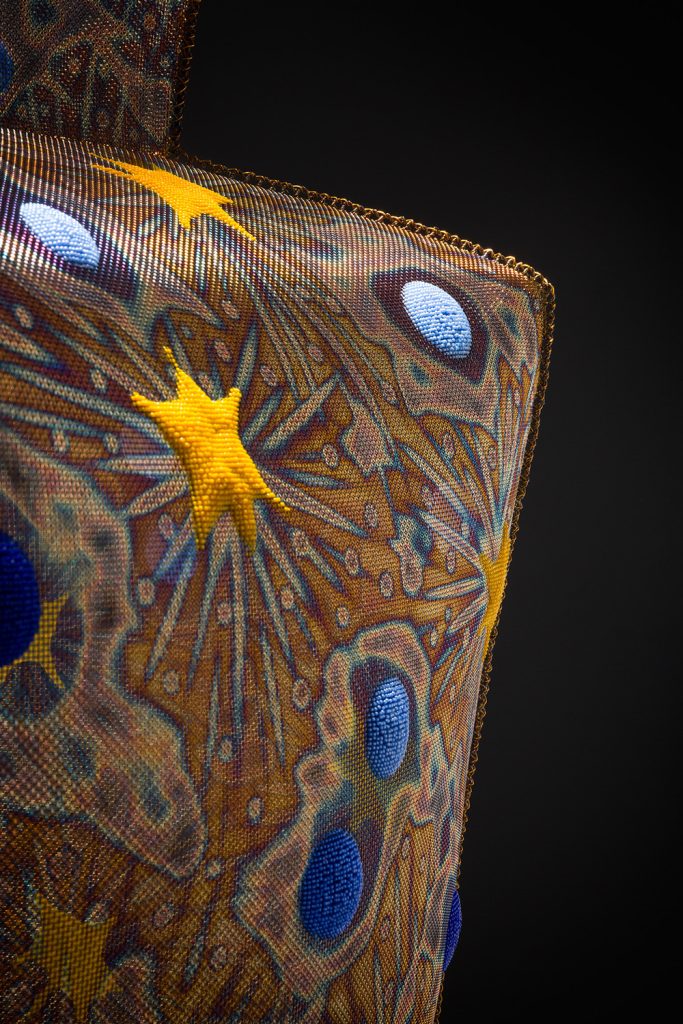

‘Celestial Vessel #8

I sort of accidentally come upon a material and then it gradually works its way into my artwork. That is what happened with silicone. I first used it as glue and then I began using it for visual effects. The most recent evolution of my use of silicone is mixing it with powdered pigment and then pressing it through the mesh and letting it dry. This has allowed me to add more colour to my work.

Detail of ‘Celestial Vessel #8

Explain how you work, where one piece is within another?

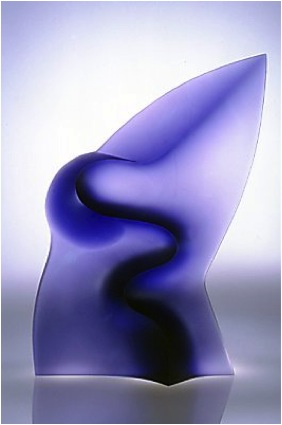

‘Blue Eliexer’

Several of my suspended “Pods” have interior elements. I first make the bottom half of the exterior casing. Then I make the lower portion of the interior form. When that form is high enough I attach it to the exterior casing. Then I bring the two forms up together and finally attach the two near the top of the piece. This is how “Blue Elixir” was made.

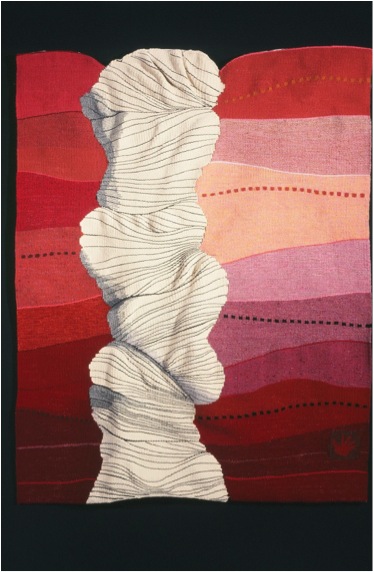

How important is lighting to the display of your work?

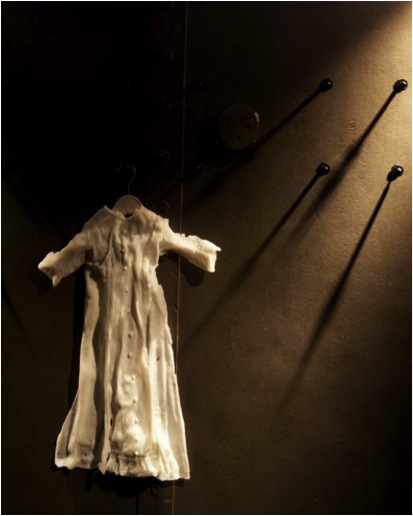

In some cases lighting can be very important. For installations I use lighting for dramatic effect and to bring out certain qualities of the mesh. In my “Primordial Muse” installation at the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington I worked with the exhibition designer to create a mysterious dimly lit display. We were able to highlight the shimmering blue light reflective quality of the mesh, making them appear almost like sheets of ice.

‘Primordial Muse’ –Whatcom Installation

Discuss your work ‘Life in the Universe’…

Inspiration?

‘Life in the Universe’

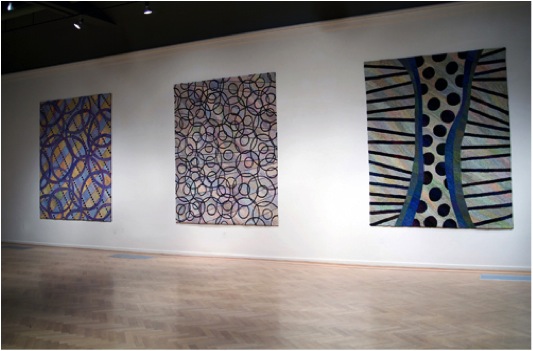

The initial inspiration came from a book documenting the monographs of radiolarians by 19th century naturalist, Ernst Haeckel. The book “Art Forms from the Ocean” was a jumping off point for the imagery. The first body of work inspired by the book was the “Primordial Muse” screens. Further development of the imagery resulted in the larger “Life in the Universe” screens. These represent my musings on the infinite variety of life forms that must make up the universe. When I exhibit “Life in the Universe” or “Primordial Muse” I like to present them so the viewer can traverse the screens, as if they are being enveloped in the imagery. Colour? The colours range between grey, amber and blue. This is the range of colour I can achieve with direct torch burning on the mesh. How fast and close I run the flame over the mesh determine the colour and tone.

Technique?

The screens are torch treated using a propane torch. So, the flame is what creates the painting/drawing on the mesh. I did not do any preliminary drawing or use any templates to produce the imagery.

Size?

Each screen is 183 cm in height x 122 cm in width. I exhibited them with about a 50 cm space between the screens parallel to one another and set at a diagonal orientation to the wall. That way the screens partially overlap one another. Location? I exhibited them at the Anchor Art Space in Anacortes, WA and at Snyderman-Works Galleries in Philadelphia, PA. A single companion screen from the series is permanently installed at Emory Healthcare, St. Joseph’s Cardiology Clinic in Atlanta, GA.

How do you organize the hanging?

I let the room and lighting arrangement determine some of the parameters of the hanging. I’m not particularly interested in what particular order the screens are hung in.

Take three pieces of very different sizes and expand on them in relationship to size.

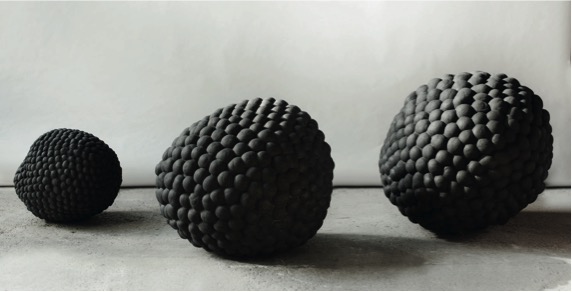

“Terra Un-firma” is a small piece made out of frayed charcoal aluminium mesh, various pins with coloured heads and some recycled ground plastic used for sandblasting. It fits in the palm of your hand and has a miniature asteroid-like appearance. The piece evokes a sense of intimacy, but at the same time gives the impression that you are gazing at a larger world through a distant lens.

“Celestial Vessel #7” is 154 mm tall; I wanted the form and scale of the piece to relate to the figure, with the vessel suggesting a human receptacle.

‘Celestial Vessel #7

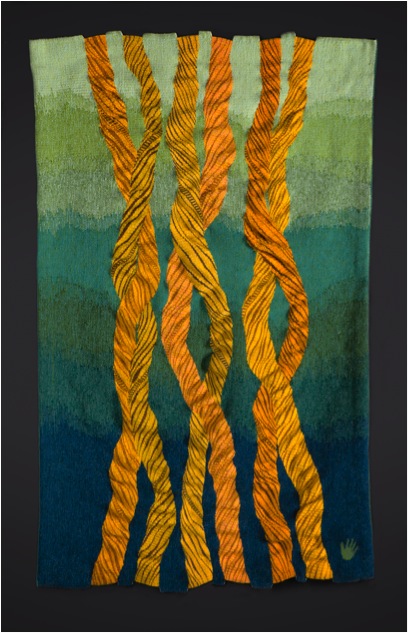

“Above Earth Below Sky” is an installation I did for the 2007 Cheongju International Craft Biennale in Cheongju, Korea. The suspended black mesh piece is almost 2 ½ meters tall, so the scale is larger then human size. This too relates to the human form, but on a grander and more elevated scale.

‘Above Earth Below Sky’

In 2016 you will be coming to Australia…

Explain how this invitation came about?

A workshop student of mine, Pamela MacGregor recommended me to Anne Kempton at Timeless Textiles in Newcastle. Pamela had recently come back from Australia giving her own workshop at Timeless Textiles and thought I would make a good fit for the program. Several months later Anne contacted me asking if I would like to have a show and conduct a workshop there.

Where and what will you be doing while ‘Down Under’?

The planning is still in the early stages, but I do know I will be spending time in Newcastle and hope to visit some other places in Australia, perhaps New Zealand as well. I wouldn’t mind finding an additional workshop venue “Down Under’, so something like that could help shape travel plans. There is a possibility my wife/artist, Eve Deisher, will also be exhibiting in Newcastle at the same time. If all goes well we both plan to make the journey and we hope to turn it into a business trip/vacation.

Where will people be able to see your work?

My exhibition at Timeless Textiles is scheduled for July 20 – August 14, 2016 and the workshop “The Art of Metal Mesh Working: Techniques and Process” will be held July 23-24. www.timelesstextiles.com.au

On a broader scale your work is in many public places can you discuss two pieces that are accessible to the public and why being there has given you such pleasure?

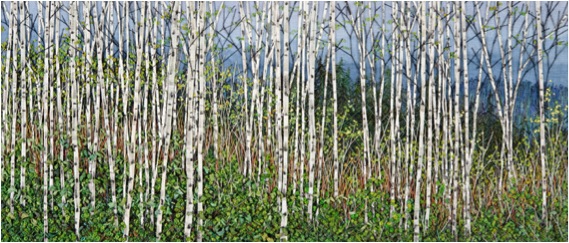

“Forest Sky” was a commission I did at the library in my hometown of Anacortes, WA. The library was built on the site where the old hospital used to be, which is where I was born. It’s even possible that “Forest Sky” is right above the location of my birth. I moved back to Anacortes in 1994 and I frequently visit the library and it is always a pleasure to see “Forest Sky” in the library’s entry lobby.

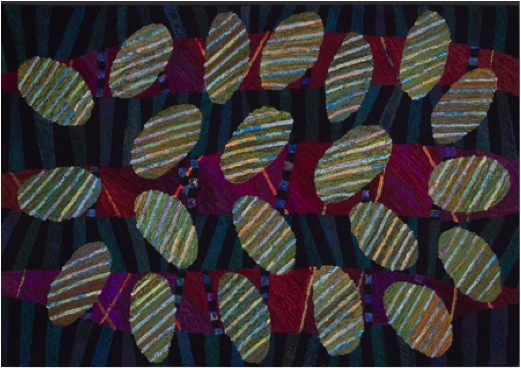

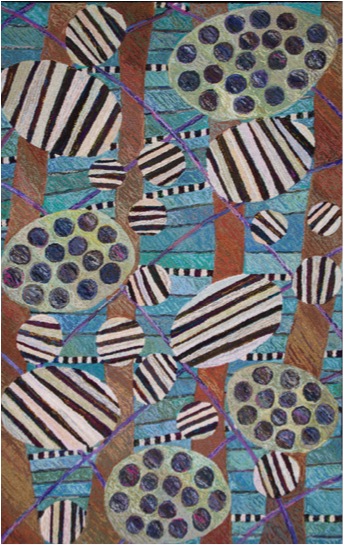

“Pattern Play” was a Washington State Arts Commission project I did at an elementary school in Snohomish, WA. The site is also a library. This is one of my favourite installations because of the enthusiasm of the school’s advisory committee and how they embraced the project. They even scheduled a daylong program where I met with each class to demonstrate how I made the installation and to answer their questions. I was exhausted by the end of the day, but it was a rewarding experience.

‘Pattern Play’

Can you give your thoughts on why Installations are becoming so well received by public galleries?

Installations are an exciting addition to a progressive exhibition program and they can transform a space into something wondrous. I believe this generates more interest in the gallery.

Contact details.

Lanny Bergner http://www.lannybergner.com/

email: lbergner@wavecable.com

Lanny Bergner, Washington, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2015

Flo Snook

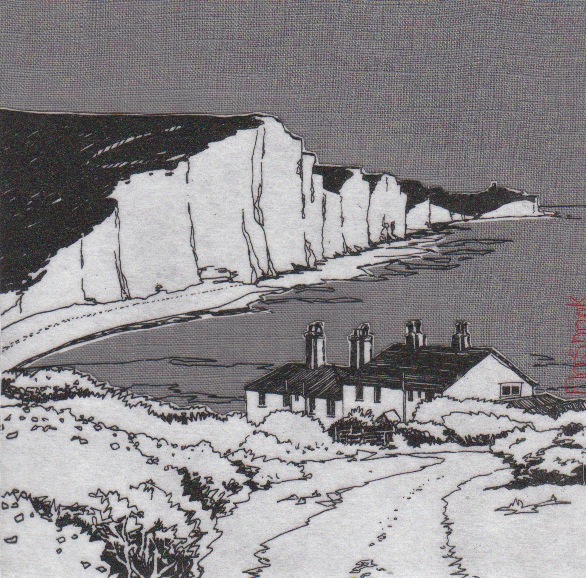

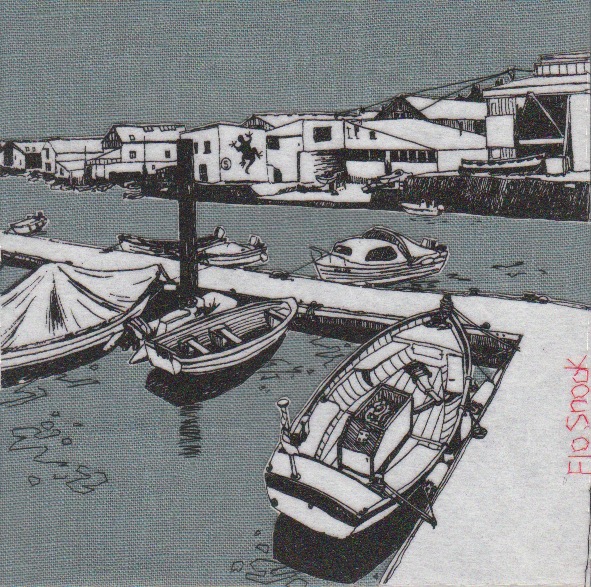

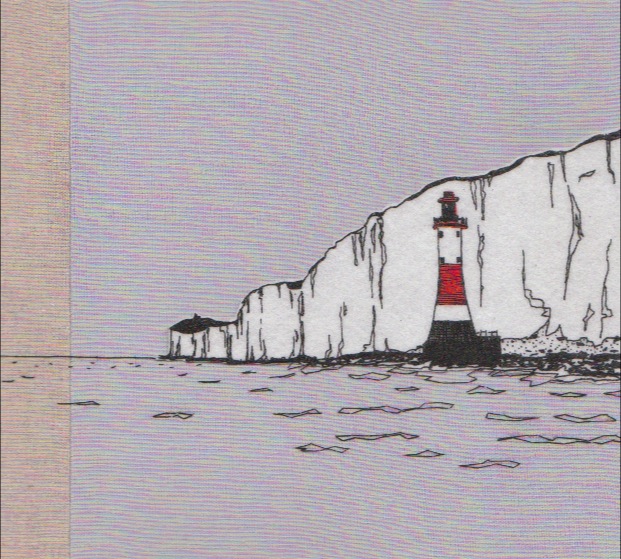

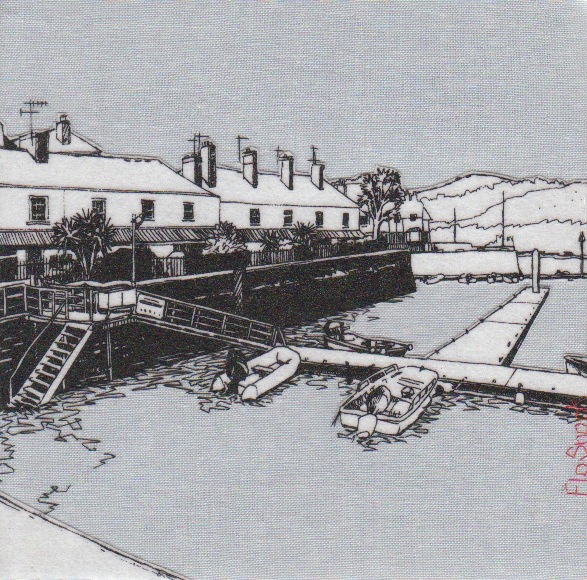

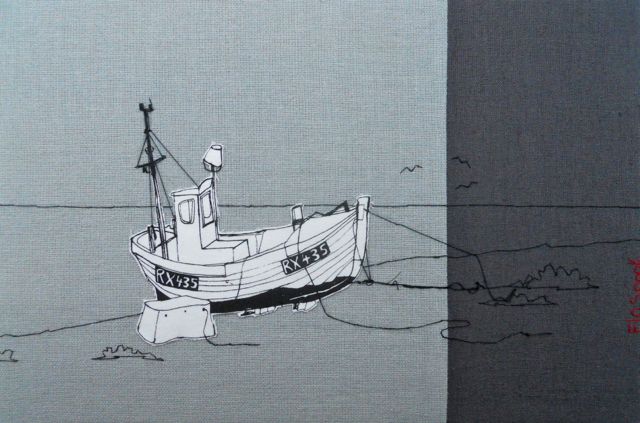

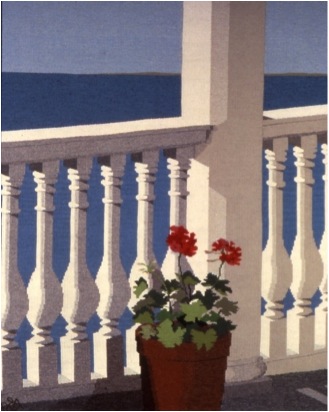

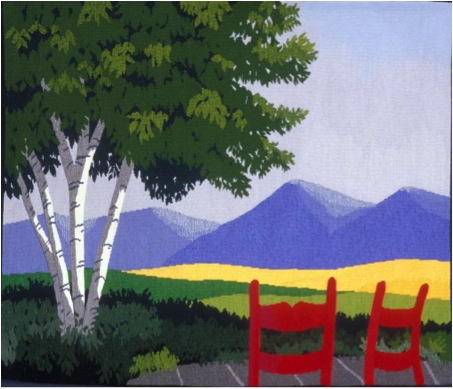

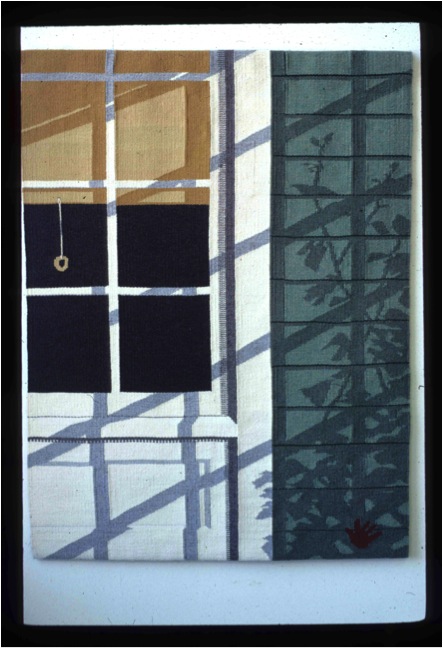

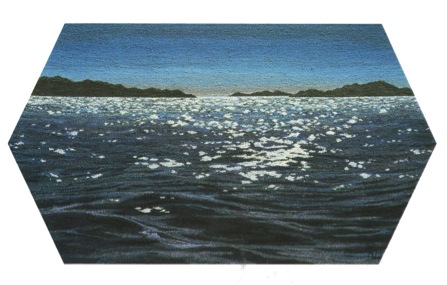

It is not just the sea but the influences made by man to the coastline e.g. piers, fishing cottages that are represented in you work, discuss.

I am fascinated by people's relationship to the sea. I love to observe how we live and work with it, how we try to impose our will on such a powerful force of nature, with the building of piers and sea defences, harbours and fishing ports, but ultimately it is Nature who will outlast us all. I often stay in a cottage by the sea in South Devon which is perched on the headland above the crashing waves, which I can hear as I fall asleep. This gives me a strong sense of the relentless power of water and weather acting on the rocks and headlands around me, and how temporal we are in the face of it.

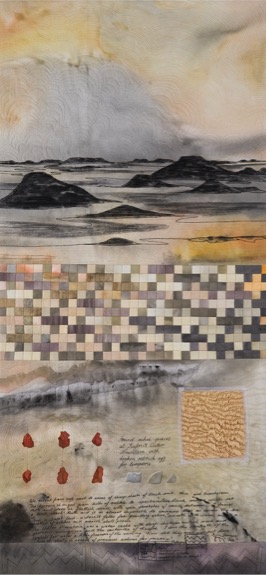

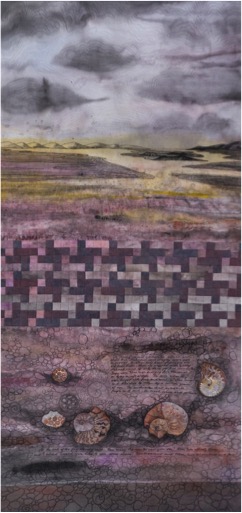

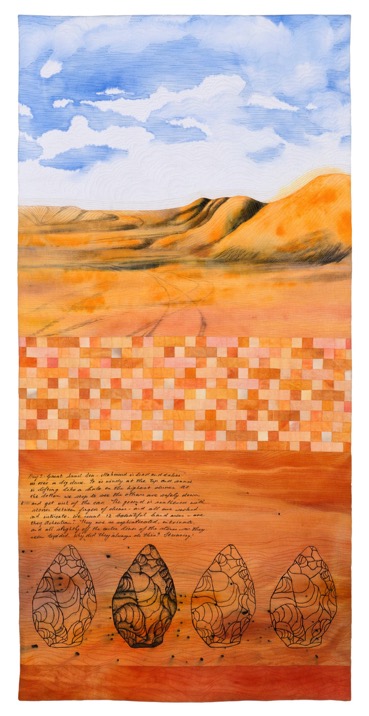

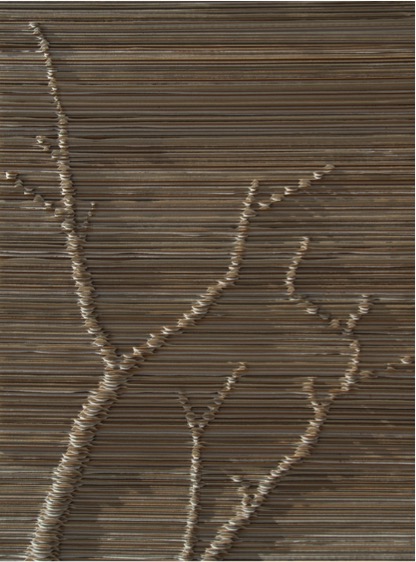

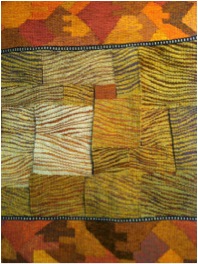

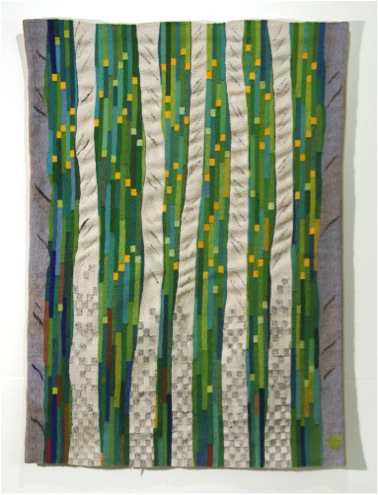

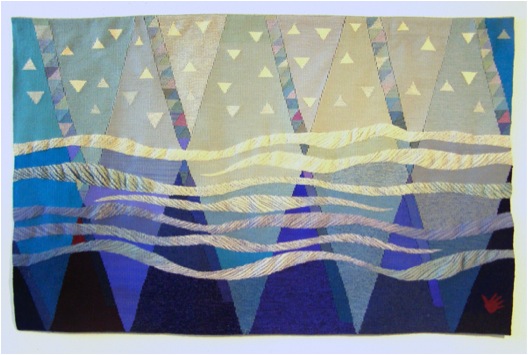

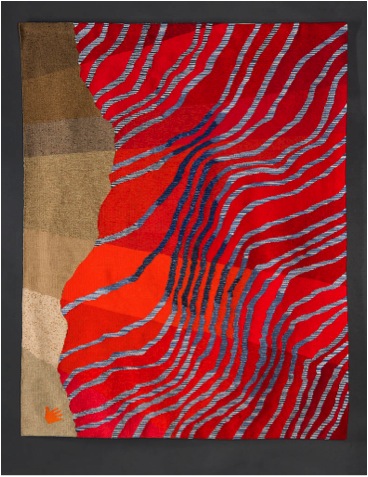

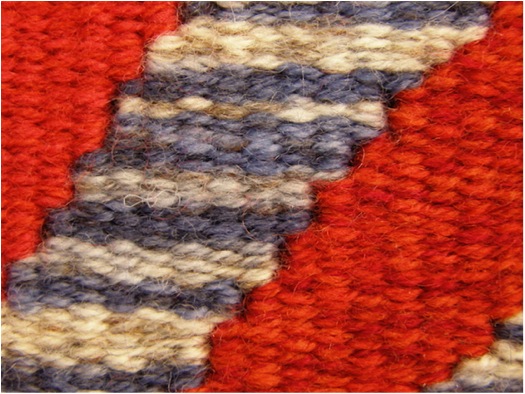

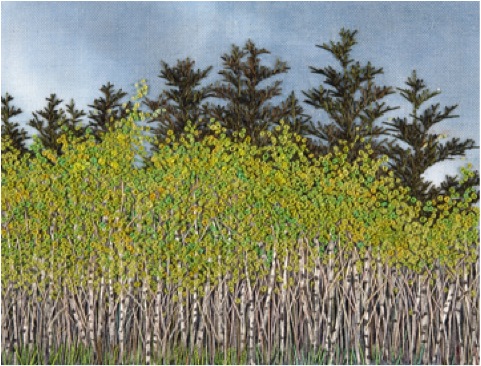

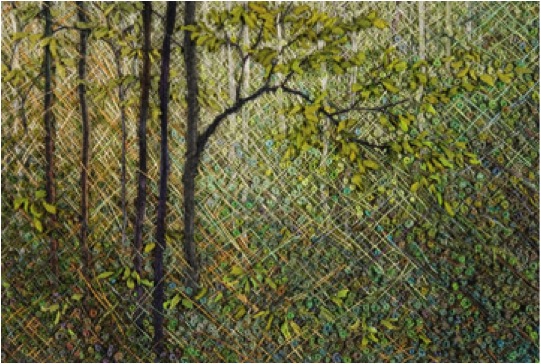

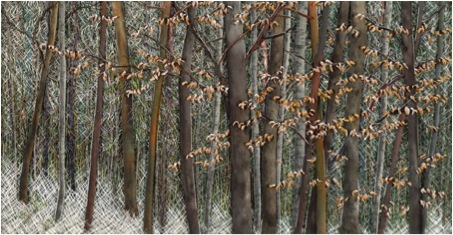

Can you expand on the ‘textile canvases’ and the technique you have developed?

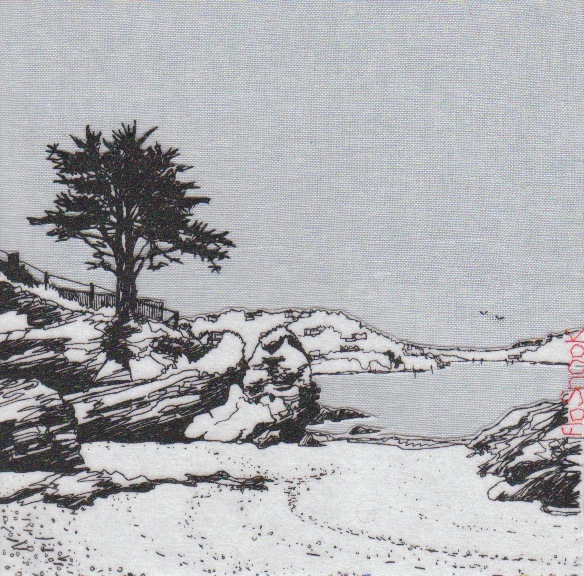

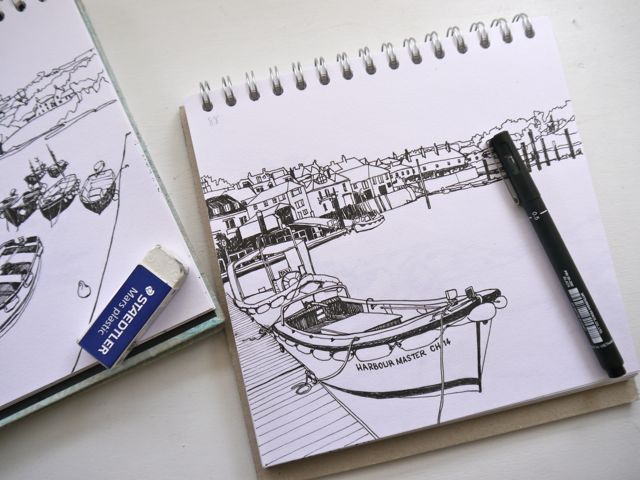

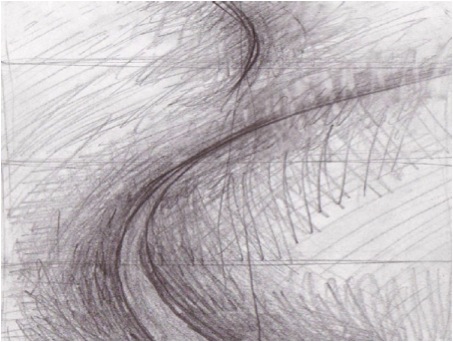

It was while I was completing my Textile Degree in 1994 that I created my first textile canvas. I was also creating vibrant landscape paintings at the time, and I wanted to create a canvas with hand dyed fabrics that would stand up in it's own right as a piece of art, and not be dismissed as a 'wall panel' with little of the same value as a painted canvas. This piece was exhibited alongside my paintings in my degree show in the Mall Gallery in London.  As my career progressed, I refined my style to a more restricted colour palette, using natural linens to express the colours I observed in the coastal landscapes. My starting point for each canvas is my sketchbook, where I create pencil sketches using the 'partial peek' method; I love the way it gives the drawings a fluidity of line as my eye travels around the landscape. I also take photos, and from these together with the sketches I create pen drawings to work from. At first I hand stitched and appliquéd all my images from these drawings, but this was far too labour intensive and I developed joint pain. So I began transferring the drawings onto silk screen so that the image can be printed onto white vilene, which I then appliqué onto the background fabrics, adding hand stitched details. This makes each canvas unique despite the printing process. More recently I've been framing my canvases in tray frames. This had added another layer of value to them and I've found that this has meant that they have fully broken into the fine art market. I am now selling in a London gallery on the Kings Road, Kensington.

As my career progressed, I refined my style to a more restricted colour palette, using natural linens to express the colours I observed in the coastal landscapes. My starting point for each canvas is my sketchbook, where I create pencil sketches using the 'partial peek' method; I love the way it gives the drawings a fluidity of line as my eye travels around the landscape. I also take photos, and from these together with the sketches I create pen drawings to work from. At first I hand stitched and appliquéd all my images from these drawings, but this was far too labour intensive and I developed joint pain. So I began transferring the drawings onto silk screen so that the image can be printed onto white vilene, which I then appliqué onto the background fabrics, adding hand stitched details. This makes each canvas unique despite the printing process. More recently I've been framing my canvases in tray frames. This had added another layer of value to them and I've found that this has meant that they have fully broken into the fine art market. I am now selling in a London gallery on the Kings Road, Kensington.

Explain your embroidered signature, both style and colour?

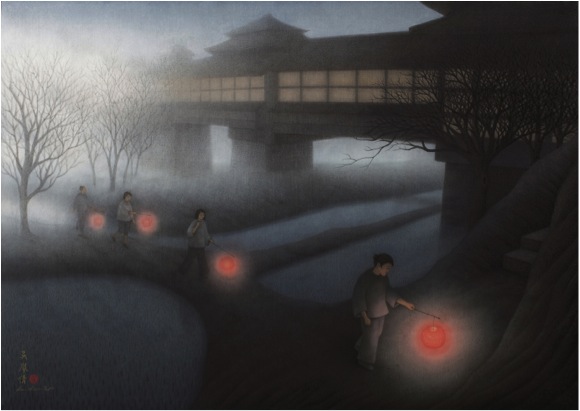

I've always been inspired by Japanese prints, with their simplicity of line and muted colours, but always with bright accents of colour here and there. They often sign their prints with a red stamp, positioned on the side of the image. It's for this reason that I always hand stitch my signature in red thread on the side of my canvas. Flo Snook is my maiden name which I decided to keep for my artwork, particularly because it is such a feature of my work, and it has to be said that Flo Scott just doesn't have the same ring to it and isn't so memorable!

Is all your embroidery done by hand?

Yes. I embroider and hand-stitch once the canvas has been stretched on the frame. I've never liked machine embroidery - for me it takes all of the joy out of stitching.

Many of your textile pieces have two or more coloured backgrounds, explain why you use combinations and how you deal with the seam?

When you look out to sea, the colours are always changing. As clouds cross the sky, their shadows create varying shades and tones which I like to capture in my work, by sewing together strips of background fabrics.The more strips of colour I use, the more challenging it is to machine sew them together perfectly parallel and then stretch them on the wooden frame so that they remain parallel. I like this challenge. As I stretch the fabric, I make sure the seams are open and pressed flat against the frame.

Your textile work, how is it mounted?

My canvases are stretched over a wooden frame (44mm deep) and then framed within a deep tray frame, giving each one depth and weight. I also create smaller textiles fixed to board, which are window-mounted and framed behind glass.

‘RNLI Salcombe’ discuss the use of red and gold in this piece?

I often like to pick out colours in the piece I'm working on to either draw the eye to the focal point or to let the eye travel around the composition. The RNLI piece was commissioned by the RNLI and I wanted to pick out some of the colours of the boat to draw the eye there, and make it come alive.

Your work is 'less is more'– discuss

I've realised that I am a very sensitive person and I find loud colours, busy places and clutter overwhelming. I often retreat to my studio when I find the world stressful and overpowering, in order to escape into the landscapes I create. I find it soothing to re-interpret the world I see into it's calm basic components. Perhaps I'm trying to re-educate the world into seeing the way I do? Perhaps I'm attempting to scrape away the layer of bling and overstimulation to reveal a way of honest simplicity underneath? I find our current capitalist society to be a delusional lie we tell ourselves; the belief that economic growth can continue at the expense of the environment indefinitely, is absurd. Nature will always win, and ultimately we'll need to curb our unrealistic consumer lifestyles and learn to live more simply. So I like to tell the story that 'less can be more'.

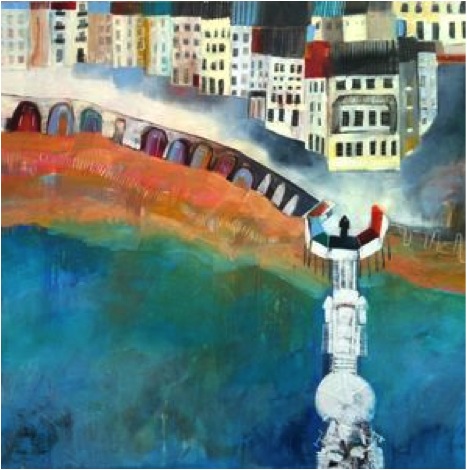

Your combination of printing and acrylic paint in ‘Brighton Pier’ discuss this aspect of your work and other pieces?

This was an exciting development of my work: I realised that I could paint with acrylic onto canvas to create a background on which I could silk screen my drawings. Although I've only created a small collection of these paintings so far, featuring Brighton and Dungeness coastal views, it's something which I'd like to expand on in future with my Devon and Cornwall work.

When and how did you introduce your accessary range?

It was through creating cushion covers initially that I found my style, so in a sense it was the accessories that came first. Over time however, I found it was important to me to be recognised as an artist, with the focus on my canvases. But occasionally I enjoy creating a useful 'product' that is more affordable than a canvas and makes a good gift for weddings and other events.

Tell us about your coastline linen cushions?

I created a range of cushions which depict the coastline (literally) of the UK in 2012, the year of the Queen's diamond Jubilee. I wanted to express something very British in this cushion design, so each one has a panel of patchwork with suggestions of the red white and blue flag. The coastline itself is silk screen and I hand embroider my name on the side of each one. These cushions have been popular with expats and look at their best with a feather filler.

On your mugs, again you have used your signature to bring a smile, expand on this, especially the placement?

The mugs were a collaboration with interior designer Terri Prior who owns the shop 'One In The House' in Brighton. She wanted to create a couple of mug designs that would be popular with tourists and with people with a strong connection to Brighton. In Brighton we have two piers; Brighton Pier (formerly called 'Palace Pier') and the West Pier, now sadly collapsed and burned down, a mere skeleton of it's former self, but which is still a very strong local landmark. So I created a pair of mug designs from drawings of both piers, with red accents on the flags. Terri decided to put my red stitched name motif on the inside of the mug to add character to the drawings and to catch your eye as you drink your tea!

Sketch books play a huge part in your art practice discuss….

The size of the sketch books you use?

I use a range of sizes. For carrying around with me when I'm out sketching, I have a small hardback book. For a majority of my pen drawings I have a 20x20cm sketchbook that I keep safe in my studio, these can be scaled up for canvases up to 40x40cm. For commissions I often use an A4 sized book or A3 depending on how big the drawings need to be. When I created a textile canvas of the West Pier for Zoe Ball and Norman Cook (aka Fat Boy Slim) I used a large sketchbook for a large more detailed drawing.

Do you take a new sketch book for each location?

That's probably a good idea! No I usually carry on with the same book.

What materials do you draw with in them?

I'm not fancy. All I need for sketching is a good 2B pencil, a rubber and scalpel for sharpening my pencil. For my pen drawings I have a range of 1-8mm pen nibs.

On the top left hand side you have a numbering system, can you explain this?

Ha ha! You noticed my code system for referring to the photos I took of the same view which I refer to when drawing in pen.

Discuss the importance of the environment in both your work and the materials you use?

I am a big campaigner for protection of the environment and for raising awareness of better ways of stewarding the land and sea. I am also a Permaculture Designer (see my other website www.permaculturedesigner.co.uk) and I like to apply permaculture to all areas of my life. It is a design system that attempts to mimic nature so that we can live in harmony with our biosphere. For this reason I prefer to choose natural fabrics that have less damage to the environment in their production as compared to some cottons and artificial fabrics, and where possible I use up-cycled fabrics too. For a time I found an organic white cotton with a very close weave that I could use as my appliqué fabric, but unfortunately they stopped producing it, so I'm back to using Vilene for the time being. Felt would have been a good replacement with less of a 'footprint' but I found that it didn't give me the crispness of line that I wanted. I use FSC rated wood for my frames and have used water based inks for my prints. In my work the environment is everything. By continually drawing the land and sea, I am falling into a deeper and deeper relationship with my beloved island, and I hope that I can draw the viewer into a deeper relationship with it too. The more we develop a connection to the land and coastal areas, the more we care for them and protect them.

You are very generous with your art work to charities can you expand on one of these?

I am currently holding a silent auction to raise money for Parkinson's UK with three of my paintings. I'm conducting the auction by email and through Twitter and Facebook. Sadly my father passed away last year after 8 years of living with the disease and Parkinson's UK were such a supportive charity to us during that time that I wanted to say thank you and give something back.

Can you explain the importance and recognition of textiles in today’s art market?

I feel it's really important for textile artists to be accepted as artists in their own right and not pigeonholed into the crafts market. It has taken me years to build up recognition as an artist just because textiles has been my main choice of medium. Last year I applied for the Brighton Art Fair, and I was accepted (as an artist) and I exhibited in September. I had applied for this art fair in the past, only to be told to re-apply for the craft fair, much to my dismay! I noticed that there were many other textile artists now exhibiting at the art fair also, so I am hoping that this is part of a trend of welcoming textile artists into the art market. This is great because textiles has so often been undervalued in the past, but now it is holding it's own.

Contact details.

www.flosnook.co.uk

studio@flosnook.co.uk

Flo Snook, Brighton, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2015

Vicky Forrester

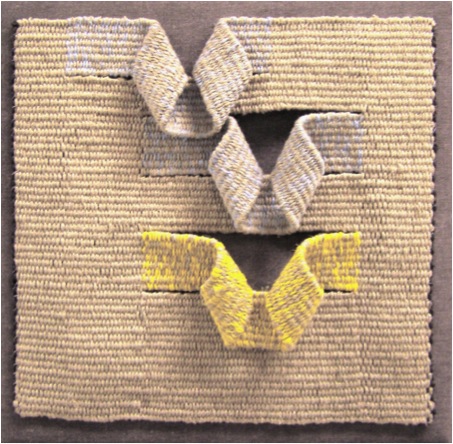

Can you briefly explain the techniques you use to create an original piece from sketch book to completion?

I’m quite playful in my approach to developing new pieces. Sometimes I’m inspired by the behaviour of a particular material, and I look for ways to exploit it. Other times ideas can evolve through extended experimentation with a particular technique.

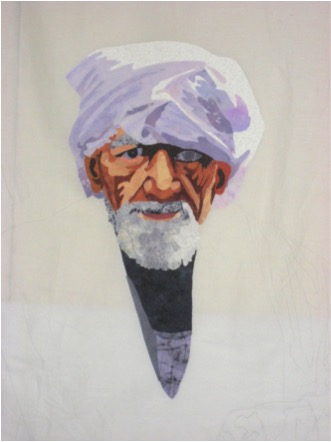

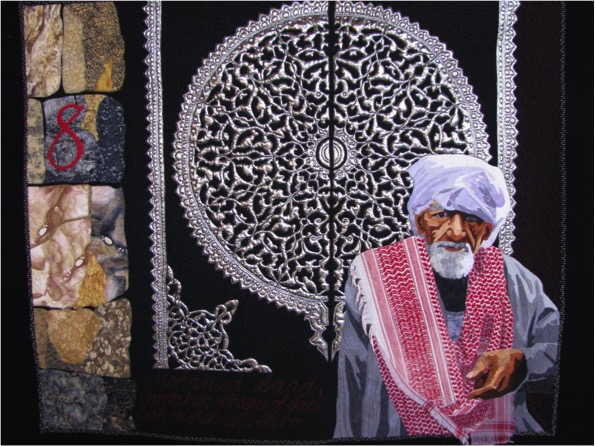

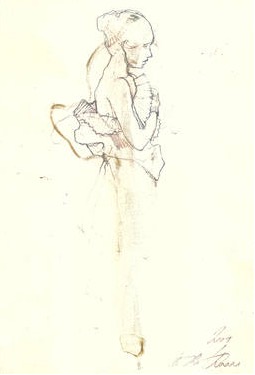

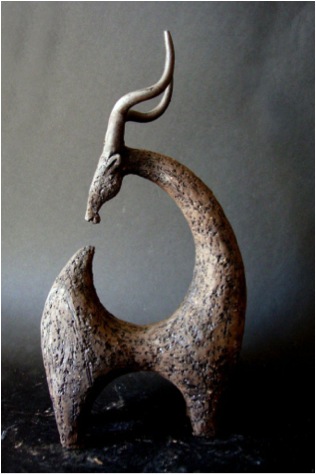

'Mystery'

In either case, beneath this process-led practice there is always a conceptual undercurrent that informs the outcome. This undercurrent is a distillation of all my experiences - thoughts, desires, feelings, perception – but especially strong for me is a connection with the elements, and my jewellery always alludes to natural form.

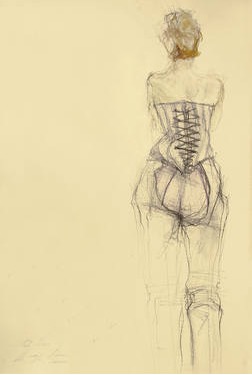

Cuffs

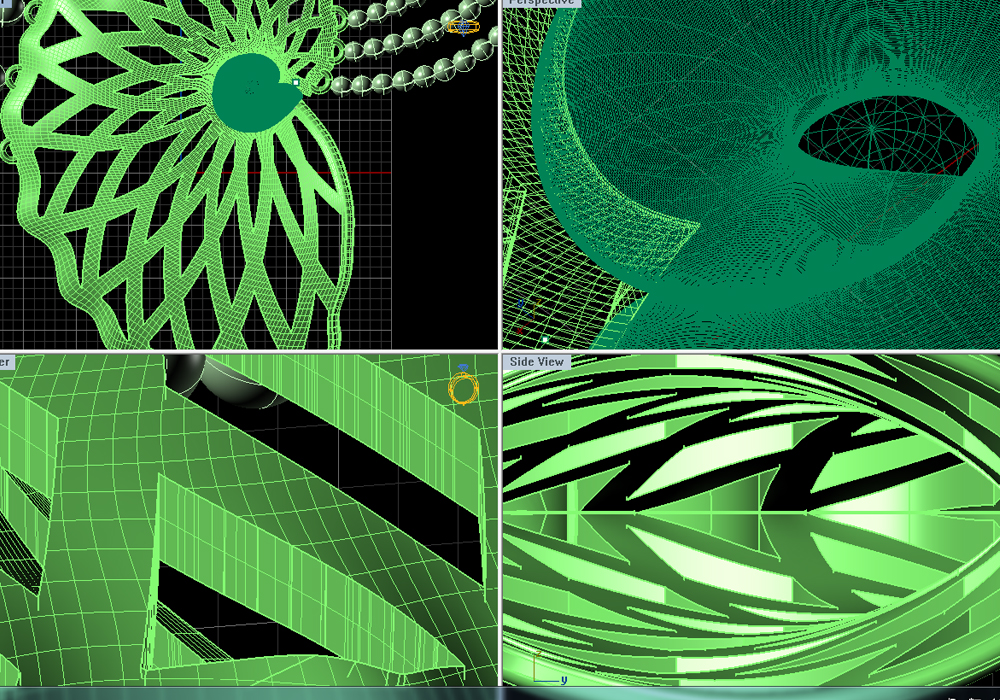

The development of the Siren Neckpiece is a good illustration of my working practice.

It’s a project that came about through taking the challenge to experiment with new technology - Computer Aided Design.

I was curious to explore how CAD might deal with my essentially organic aesthetic. I joined a course to get to grips with the technology, and while I had anticipated I would end up producing a model ready for rapid prototyping – thus the fear of putting the maker’s hands into early retirement - actually I was surprised to realise that my resulting design would be far better made in the workshop using traditional means.

The process itself – designing in Matrix - resulted in my creating a piece of fine jewellery that I wouldn’t otherwise have envisaged and I’m impressed to be able to view and show the piece accurately from every angle through 360˚- before it ever gets made.

I was interested to find that when designing jewellery with CAD you must already have a good knowledge of subject-specific materials and making processes to be able to factor in the quirks of materials and processes eg understanding construction techniques, the impact of scale, and all the tolerances required.

The Siren Neckpiece began with a family day out to Margate. The daytrip provided great inspiration for my CAD Project.

I was interested that the Shell Grotto in Margate has no known beginning though many stories abound. Discovered accidentally in the 1800’s, it became a popular Victorian attraction and the lamps they used to light the underground passageways produced soot that has inhibited the carbon dating process. It has been suggested that the Phoenicians built the grotto 3000 years ago, to worship the Goddess Tanit – hence also the locally named ‘Isle of Thanet’. But perhaps it was a Victorian Folly, or a Pirate’s treasure store – or maybe even a Siren’s haunt!

Using these thoughts, experiences and images as source materials I looked to develop some designs that I could explore using CAD….

I’m pleased with the final outcome; the Siren Neckpiece still maintains some fluidity of the organic approaches I would normally use – it can sit comfortably amongst my existing pieces - and I’m interested to find that through the choice of materials it has tipped me towards a fine-jewellery quality that I have not previously explored.

Expand on the importance of ‘one off’ pieces in your work?

When I explore a technique or material I’m particularly interested to understand how the protocols of that medium can be best exploited to make something that cannot be easily made in another way. So for example, with my growing understanding of CAD, now I see that it is less interesting if used to design an object that might be equally well carved in wax; it’s pretty cool as a rendering tool for showing a 3D experience of your intended design, but it gets really exciting when you develop very complex 3D designs to output using the ‘sintering’ process, where a laser passes through gold dust to make solid your dreams!

So, in relation to my preference for making one-off pieces of jewellery (and small batch production runs), my mind is always working in this way, seeking out new and better ways to exploit the chosen medium and technique, to more precisely express my intentions. Thus each piece I work on is an evolution of the last. For me this interaction is important. It runs counter to the tide of popular jewellery/craft/design culture that now encourages ‘production’ with a more/cheaper/faster approach. I think my clients enjoy that the pieces I make for them are unique.

It also requires an element of trust from my clients. If you see a coral ring that you like on my website, I can make one for you. It can be similar, but not the same, because I must sculpt it in your size in wax before casting it in your chosen metal. I will need to interact with you; you can guide me towards a preferred characteristic and I can put love into the making of it because its materialisation is not some hands-off series of standardised processes that get us from A to Z. It will inherently carry with it the accumulated knowledge and experience of every coral ring I have made before it. It will also be an expression of the maker thinking about you. It will be uniquely yours.

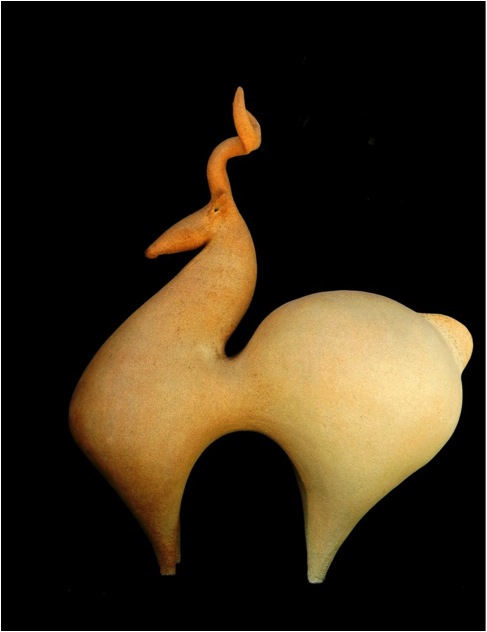

‘Totem’

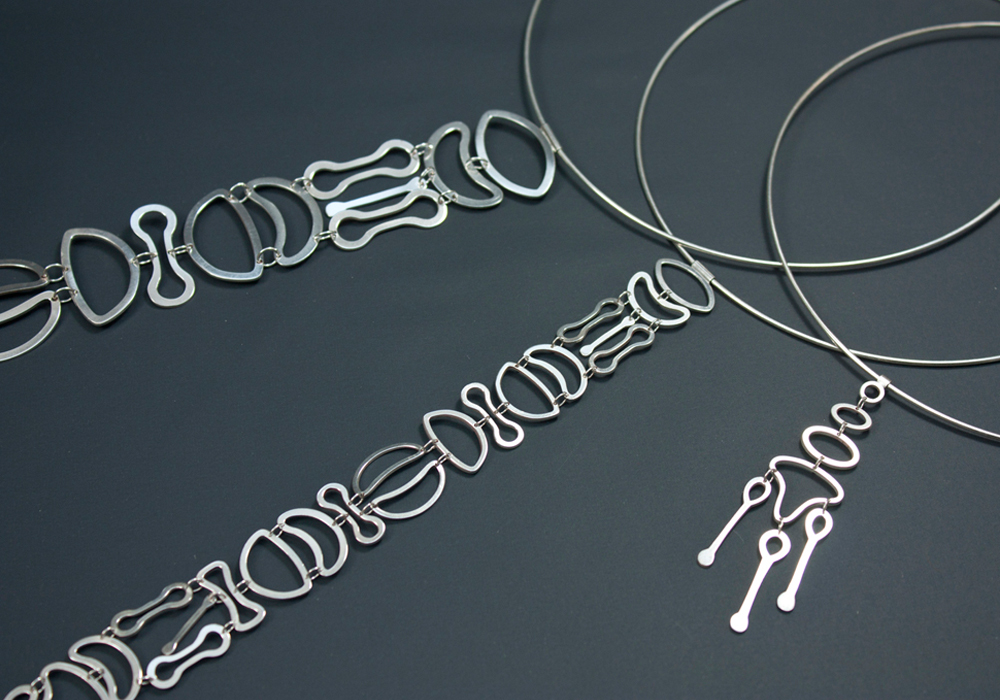

I find an interesting challenge in the use of technology where it’s inherent nature leads to multiple production. I’m not averse to exploiting this character to further explore a theme – as with my Totem collection.

In this instance, the concept evolved from thoughts of the body, our bone structure and movement. Early pieces were an expression of this articulation; a long column of links became an external vision of the spine; conversely pulled straight by gravity the column causes an exaggerated view of the body’s movements. Each of these links was made by hand and so it was a slow process to develop the concept. Laser cutting provided a means to create multiple units that I could then use to explore new assemblages, hence ideas were able to evolve faster, and in new ways.

You gained your BA Hons. In silver smithing in 1990 what stands out now, 14 years later that you wish you had either learnt or appreciated earlier?

My years at college gave me the freedom to lose and find myself; In discovering that there are no rules to the creative process my ideas became free and flowing, but I think perhaps I was prone to taking life a little too seriously. I hadn’t yet understood that I was allowed to play, and I could have spent more time just doing rather than thinking about it. I came across a quote the other day (courtesy of my favourite Yogi tea) that would have served me well at that time: ‘Stop playing serious and seriously play.’

‘Embrace’

You describe your work as Powerful, Precious, Playful can you expand on each in relation to your work?

Jewellery is magic! When worn it becomes a powerful entity that can instantly transform your mood and your energy levels. It’s also a powerful communicator and so much can be expressed through (and read into) in the kind of jewellery you choose to wear.

‘Spirit Ring’

The notion of preciousness goes beyond material; it describes the relationship we have with our jewellery. Jewellery becomes precious only when we choose to engage with it and for me it’s about it’s history intertwined with your own story. It’s such a personal experience.

I love that it has this ability to transform the wearer and in my jewellery designs I like to exploit this element of play. I seek ways to create versatility in my pieces so that my audience will find numerous ways to wear and enjoy them.

Explain about your ‘Mark’ on your jewellery?

Design

Seeded in nature – the world that engaged me through childhood - my curiosity has always found creative expression through physical form. The tactile and physical elements hold equal importance to the visual. My ‘mark’ is an articulation of the ‘now’ – my current perspective formed as consequence of all accumulated thoughts and feelings – in relation to those ‘natural’, “tactile’ and ‘physical’ undercurrents. Because the creative process is a narrative of my experience (thoughts and feelings, fantasies, realities, my joyous moments in life) this affords me freedom to explore simple and complex ideas, to make drama, all-show pieces, and quiet, powerful pieces too. Over 30 years this has lead to the emergence of 6 distinct collections, each one answering to a particular intention, mood or desire. Distinct and yet distinctly related, I continue to develop new work for the collections as I am drawn to explore these same themes from ever evolving perspectives.

Importance and the meaning of the Mark on jewellery?

A walk through any museum will show you the importance of jewellery in deciphering our history, back to the most ancient of times. Materials, techniques, concepts – all record the evolution of our species, since the beginning of our time. Humankind has always held it precious, hence it survives as a record keeper of our stories, our values, our relationships, how we lived, where we died. It’s an unparalleled communicator. This most ancient of art forms continues to fullfil our primitive urge to express, empower, protect.

‘Joy’

With this perspective then, as makers of jewellery we have the capacity to engage with humanity on many profound levels. Through our personal mark we are in a position to add our unique voice to this conversation. Fired with the maker’s intentions, our jewellery becomes invested with palpable energy, meaning and value that can carry information far into the future.

Where do you go for your inspiration?

Actually I think all my daily experiences, even the most mundane, seem to find ways to influence my ideas; I’m not sure it’s possible (or desirable) to turn off the creative or curious mind, once engaged?

But my ultimate battery-charging, spirit-lifting, soul-feeding place to go is the seaside. I have strong family connections with the south west coast of Ireland and west coast of Scotland and most of my formative years were spent in one place or the other. The tides, like a breath, wash the city grit from between my ears. In, out, to the end of time. Scrambling across incredible rock formations to find rock pools teaming with jewel-like life-forms; palm trees and gorse beside golden sandy beaches, crystal clear waters, wind in my face, pockets full of stones…. Up from the shore, the damp-sweet smell of bog myrtle and bracken, raspberry picking along the hedgerows…home to family. Happy days!

My camera is an all-the-time essential tool that I use to capture, record and document the interesting moments in life. Before the camera, experiences were committed to memory, and I visit them frequently when my eyes close. Now they’re all on my phone-camera. I hope it’s not making me lazy.

Tell us one or two special story / stories of a piece you have made on commission?

I love the collaborative challenges of working to commission; It begins with a jumble of fragments, and between us the client and the maker must conjure them into dazzling solid form.

Usually the client brings an ephemeral element - a wish, a passion, a story. Often there is a physical element – a precious stone, an unwearable inheritance, a preference for material. The third element is the maker’s aesthetic. All of these ingredients must be drawn together, mindfully working with the material, it’s behaviours and the processes required to transform it. Metal is an endlessly forgiving material to work with; it yields sonorously to the hammer, can be pushed, scraped, filed and polished into form, or entirely transmuted through fire to a new vision of beauty. I like that the process often begins with recycling. A broken chain, an heirloom ring, all are given a chance to become something new, to live with relevance!

Here is a constant reminder of the transient nature of all things. I hope that my creations will be enjoyed and treasured, that they will be lovingly passed from one person to another with an endlessly expanding story. However I must accept that one day a new owner may give more value to the metal than to the form I have given it. The narrative of its changing form may be carried on through generations, and perhaps also at a molecular level there remains an ionically- bonded memory between the metal and it’s long history!

‘Flowing Ring’

Flowing Ring, recycled from the client’s unwanted 18ct white gold jewellery. The old rose-cut diamonds, also inherited, came from a beautiful and dazzling tiara that had no place to shine in these modern times.

Discuss your Medusa Range?

Inspiration

The first pieces I made in this collection were inspired by ‘material’ – I loved how this fabulous chain coiled and twisted, and I looked for ways to exploit this behaviour.

'Rattlesnake’

Subsequently I came across this woven leather cord and it provided a means to create more structured forms that could defy gravity or wrap the body. By adding sterling silver elements to my structures this gives sharp contrast to the soft appearance of the leather, meanwhile also suggesting latent power, perhaps a little dangerousness to the resulting pieces.

The name ‘Medusa’ derives from ‘metis’, or sovereign female wisdom. I chose this name for the collection because I found these pieces seductive, and hypnotic. As the collection grew I sought to understand this primal connection. Unlike the image portrayed of Medusa, I felt empowered by my snake-like forms, and so I sought out her deeper secrets… The story of Medusa as told in Greek Mythology is a neat exercise in the subjugation of female power, and her story, pertinent as ever, echoes through the centuries and through every culture. A woman is ravished because she is too beautiful to resist; on discovery, she is blamed for her beauty. She is cast out as temptress who must be punished and she is eventually slayed. In naming this body of work ‘Medusa” I look beyond the traditional mythology of the snake-haired, petrifying gorgon to reclaim her roots as Snake Goddess, who’s beauty is her soul. Powerful she, who holds in her hands the timeless cycle of life.

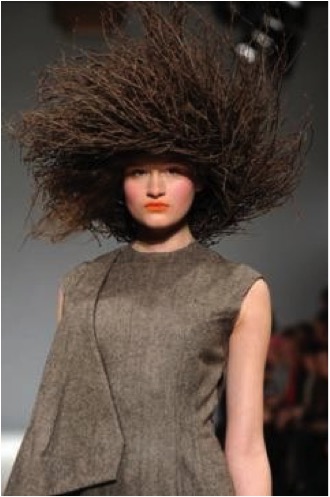

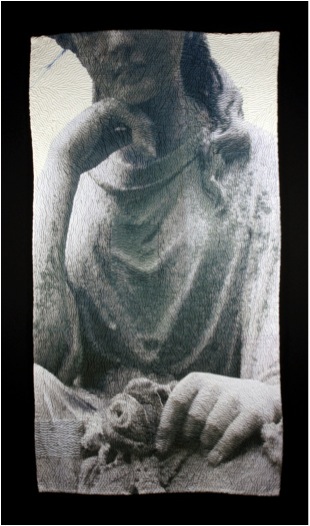

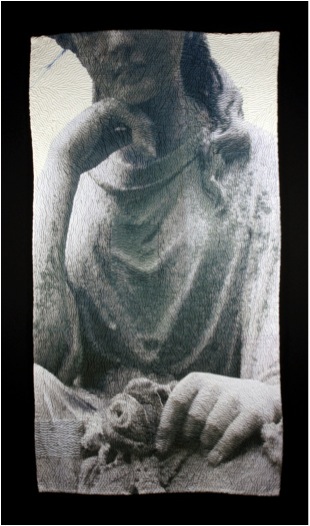

On photography

Photo by Rowan Papier

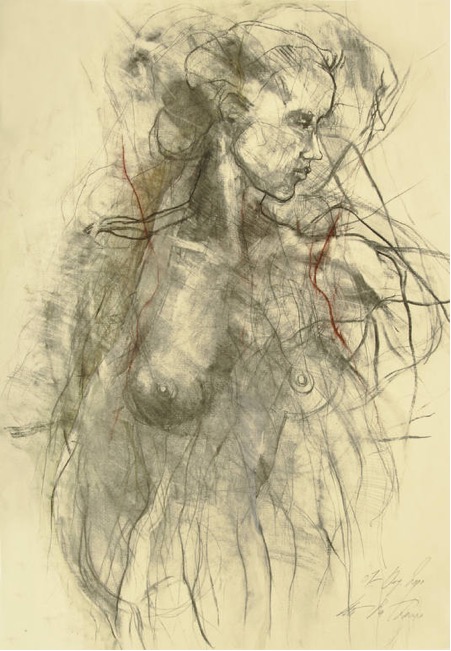

When I photograph my work I tend to take quite neutral shots that try to show the sculptural element of the pieces. Sometimes, as with this collection, this isn’t enough. These works needed to be seen in context, and I gave the photographer free reign to portray the Medusa collection as he felt inspired. I love this raw, charged imagery that he produced. The model, his muse, has an intense energy that draws parallels with Barbarella and the feminist view of Medusa (female rage) all at once.

Dressing up or Dressing down

Of course, not everyone who wears the Medusa Neck wrap chooses to make this, along with well-drawn smoky eyes, their only item of attire!

The playful element is an important aspect of this collection, and each piece can be worn in as many ways as you want to try them. The medusa ring can be worn as one coil on the thumb, or twisted to coil across 2 fingers for a more dramatic look. Or perhaps you need a little something to hold your scarf in place. I twist these Medusa pieces into my loose-knit jumpers too.

Discuss in more detail ‘Medusa Arm Wrap’

The Medusa Arm wrap has a similar versatility; Stretched out the piece of leather is almost a meter in length, so the multiple coils can be used to give three-dimensional structure, or to coil around any part of the body.

Discuss Helix and the inspiration of this work?

The Athene collection also explores how coils can be used to create structure. In this instance the collection was seeded from exploring ‘process’. Using binding techniques I wanted to create forms in silver that would be light and structured, that would also respond well to the body’s movement. Spirals and tendrils seemed to be a natural outcome to the slow process of binding, (hence Helix) and through experimentation I began to understand how the desired three dimensionality of form could be dictated by working around a shaped, internal framework.

I chose the name for this collection because Athena was known as both warrior and weaver. The pieces evolve through a similar repetitive process, creating structure and dimension from threads, and the final outcomes seem to me fierce and proud.

‘Athena’

Your piece the ‘Venus Rose’ has been designed to be worn in different ways. Discuss the importance of the versatility of piece.

It’s actually quite some challenge we jewellers face to make an item of jewellery that absolutely anyone can wear. Before we even touch on style and preference for a ring, necklace or cuff we must pay attention to the dimensions of wearer. ‘Average’ measurements, as with fashion, are never accurate enough for a well fitting neckpiece, and so in the Venus Rose I wanted to explore ways to make it so that could fit anyone.

‘Venes Rose’ (desire)

The solution I found was to weave the thorny form in one long length, thus creating a wrap that can interlock at any chosen point. In the process the piece becomes ever more versatile so it can be worn high as a choker or loose, more like a collar, depending on the clothes you want to wear with it. And of course being a single length of woven material, it can be used to wrap around any part of the body!

How do you think jewellery should be documented by the owner?

Jewellery should be purchased for wear, should be worn and enjoyed, and passed on with love. I like that jewellery is held most precious for the story it carries; certainly it grows richer, gathering a new kind of energy as it lives through the experiences of the wearer(s).

My Great Aunt left little notes in the boxes of the jewels she felt to be precious; other items held their value in Chinese whispers, though time (and the internet) often revealed another story, certainly in the case of the treasured Lake Como pearls that in years proved flaky and faux. Perhaps she had meant: ‘from the pearl of Lake Como’ and not ‘pearls from Lake Como’ as we had understood it!

What details should be recorded for future generations or owners?

Of course, the hallmark tells a small part of your jewellery’s story – the maker, the date, the place of making, the type and quality of metal it’s made from. The living history – myth and fact interwoven – holds the greatest room for mystery, intrigue, delight. Where does your mind go at the mention of Kohinoor? Passing on the stories behind a piece of jewellery will always have the greatest relevance. Queen Victoria had the Kohinoor’s original rugged beauty cut and polished into her vision of beauty. Only the ‘now’ owner knows the true value of their jewellery regardless of the perceived material or historical value. Ultimately if they don’t like it, if the story feels irrelevant, they may have it melted, just as so many of my clients’ commissions have begun, to be re-fashioned into something with greater personal resonance. This leads me to embrace the ephemeral nature of all things; everything worldly is a constantly shifting arrangement of the same atoms and molecules. As a jeweller, I am pleased if somebody can enjoy my various atomic arrangements. But it’s only ‘now’ matter. Tomorrow it could be transformed into someone else’s dream.

What lead you to opening Flux Studios?

My own journey into becoming (and surviving as) a jeweller gave me insights into the challenges and pitfalls that you must face when first setting out as a maker. It’s not an easy commitment to make, and I applaud anyone who makes that tough decision to follow their creative path.

I’m a big advocate for adult and community education, especially in the creative field; it provided me with a route into finding my passion for jewellery, and I know first hand the many benefits that result, on a personal, social and communitywide basis. For this reason I have always held the teaching element of my working practice as a vitally important link in my creative activities. In 2008 I decided to take a leap, to leave a part time teaching post and to use the redundancy money to set up a studio where I could marry these two major influences together. My aim was to produce my own work, and to provide a fully equipped working environment where other jewellers could develop their practice in a supported, mentored, community environment, and where I could continue to offer classes and courses in jewellery for the local community.

‘Peace’

Flux has proven to be a very successful model, and there’s a real sense of community here that has taken on it’s own inspirational dynamic; although the business is fundamentally mine I describe the activities and achievements here in terms of ‘We’ and ‘Our’ because without the willing participation and generous contributions of the people who use Flux Studios, it could not exist.

How does Flux operate?

Flux Studios is a specialist jewellery studio and jewellery school combined. Our remit is a simple one – to provide a platform where expertise, enthusiasm and the open exchange of ideas combine to inspire creative genius! In practical terms this means:- We provide opportunities for people to explore and expand their creative potential using jewellery as a medium, through jewellery classes, courses and workshops. We provide a dynamic studio base for aspiring jewellers to explore their business potential and achieve success, offering a fully equipped jewellery workshop, extensive library, mentoring and support network, learning and teaching opportunities as well as exhibitions and promotion – all through our membership scheme. We achieve a unique dynamism in the Studios by integrating classes and workshops in jewellery-making alongside professional jewellers who are carrying out their activities to develop their business. In this way students are inspired to develop better skills, and the professionals develop their communication skills and gain feedback on their work as it evolves. Audiences are developed and skills and knowledge shared.

Combining a teaching environment with a professional working studio Flux has a skills pool that makes the whole far greater than the sum of its parts. Because we are small we can focus on the unique individual need, inspiring people to achieve excellence. In providing a home to both aspiring professionals and the interested public we have evolved a holistic creative studio environment where the individual skill sets of all our users are valued and shared to enrich this community as a whole.

Discuss, membership to Flux?

Anyone with a passion for making jewellery, and the skills and training to work autonomously and safely in the workshop, can apply to join. Flux membership acts as a proving ground for future jewellers; in sharing expertise the group has the potential to be greater than the sum of its parts and ultimately this improves the probability for each member to create successful businesses and enriching careers in jewellery.

Flux members have access to our exceptional facilities, mentoring, exhibition opportunities, skills development, teaching opportunities, community interaction and audience building, and our network of Flux Alumni that now spans the globe, all for a nominal monthly fee. When a new member joins at Flux I encourage them to feel a sense of equality and ownership within the studio, right from the start; this gives members autonomy in (and respect for) the space and this instils real confidence to grow, share and learn.

This also makes it a great place to work!

Have you thought of E coursed for those of us who don’t live in London?

Ah, if only there were more hours in the day, more days in the week! But in the meantime I can recommend a great book…

Elemental Jewellery by Vicky Forrester

ISBN 9780956438270

£18.99, from all the best book stores.

Or order your signed copy direct fro the Author

Contact details.

Vicky Forrester, London, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2015

Jan Hopkins

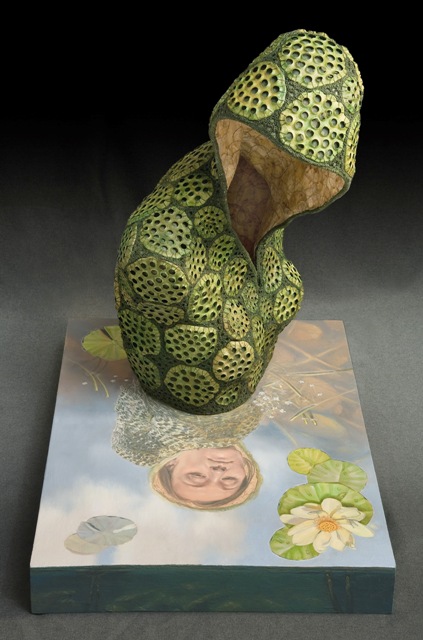

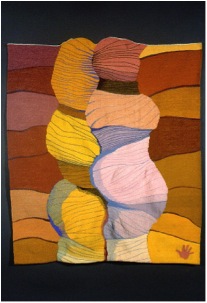

Can you discuss the way you continue to use organic materials such as, plant pods, flowers, and peel?

I love the challenge of finding new materials that I can use in my work. I continue to find better ways to use and preserve materials that I work with now. When you find your own materials that haven’t been used before, there are no rules that inhibit exploration.

‘Agave Within’

How does symbolism play a large part in the use of special materials in your work?

Symbolism played a larger part in my earlier work. “Young at Heart” that is described in a paragraph below is a good example. “With Child” is piece that I used Egyptian symbolism by using colour and emblems significant to life, regeneration and fertility. I used lotus seeds and lotus pod tops symbolic of rebirth, the frog symbolic of fertility and regeneration. My choice of colours are also symbolic, green to new life, red of life and victory and black of fertility and life.

‘Young at Heart’ Detail

Discuss the difference of being an urban collector is?

I think I understand your question to be; what is the difference between traditional foraging and gathering alternative materials that have been undiscovered. In many ways, they are very similar. The difference is historically, hunter/gatherers searched for the best materials to use to make clothing, utilitarian tools, vessels, etc. The materials were experimented with and processed to make articles that were needed in everyday life. I work with materials that are not ordinarily used, but that I can find in abundance.

I find ways to use them to create artwork. The materials I use do not have to stand up to utilitarian use, but I have to experiment, process and preserve my materials to be strong enough to withstand time.

‘Old – Soul’

How valuable was your reading disability to your artistic career?

With any type of disability or adversity in life, it makes you stronger. It challenges you to overcome and think differently.

What was the initial magic you saw in basket making?

Native American Baskets at the Heard Museum in Arizona caught my eye. I was fascinated by the fact that the baskets were made of grasses, roots and bark that were processed and refined to make beautiful utilitarian vessels. The moment I saw them, I felt that I needed to find out how to make them. It was an immediate passion.

You have visited museums extensively to view baskets – discuss the importance of these visits to your knowledge?

When I go to museums, I look at all types of art, but I am drawn to fibre and three-dimensional objects, not necessarily strictly basketry. Going to museums and galleries are always important source of inspiration.

Do you have a favourite museum that you know will always have a great display awaiting you?

I enjoy all types of museums, but, my favourite museums are fine craft museums that display work that I relate to.

Do you feel that this is an area that is under rated in museums collections?

Not at all, I believe that contemporary basketry has a solid place in permanent museum collections and private collections. I have been fortunate enough to be included in several museums in the U.S.

‘Vibrant’

How important is touch to your work?

As the artists?

My work is very tactile, so I would say that touch is a very important part of my work.

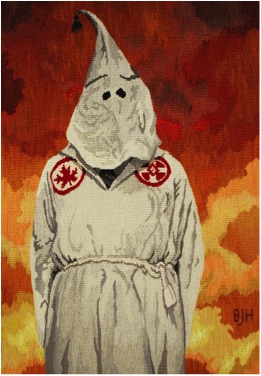

‘Oh Canada’

Can you discuss 4 of your works that will allow others to understand the depth of your work?

All of my work is narrative in one way or the other. In the beginning the narrative was identified by the title of the piece. As discussed previously, I delved in symbology. But my newer work includes words and quotes.

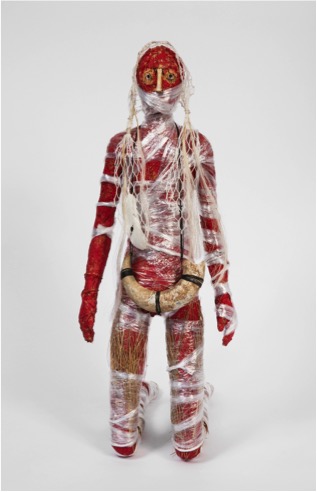

‘Tolerance’ by Jan Hopkins, photo by Ken Rowe

For instance, the pair of shoes titled “Tolerance” has the word “judge her when you’ve walked in her shoes”. The story behind this piece was about a soccer mom of three. After an unexpected divorced she had to find a way to make a living. She became an exotic dancer in the evenings so that she could care for her children during the day.

A piece from the Child torso series “Young at Heart” The piece is about aging and time. I used silver dollar pods and skeleton leaves and the time consuming quilting technique all relating to life, time and aging. The quote inside this piece is by William Butler Yeats, “The innocent and the beautiful have no enemy but time”.

‘Young at Heart’

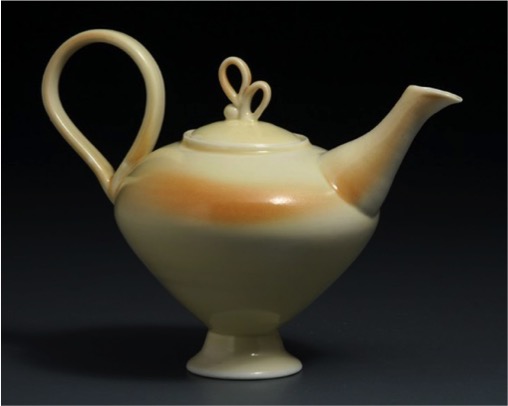

“Oh Eleanor” is from the “Women Icon Series” and it is a homage to Eleanor Roosevelt, one of the most outspoken women in the White House, known for her intelligence and concerns for women’s issues and human rights achievements. She was an excellent speaker with a quick wit. I chose the quote: “Women are like teabags. We don’t know our true strength until we are put in hot water” to portray her personality and her ability to speak clearly to get her message across. "Oh Eleanor" is more whimsical than my previous pieces that I have created for this series and intentionally a bit sassy.

It is made part human, part teapot. The complex design is made to look like art nouveau flames moving up from the base of the piece (made of grapefruit peels) and steam coming off the flames (made of thinly stripped and stitched cedar bark). Ginkgo leaves were used to symbolize teabags dropping into the teacup. I used these on the top part of the bodice along with lopped lacy waxed linen to also visually create a period style dress form. The spout and handle (arms) design is asymmetrical to visually create the feeling of a teapot rather than arms.

‘Oh Eleanor’, photo by Ken Rowe

I worked on collaboration with my husband on a series called “Reflections”. The piece entitled “Reflections: The Dance” gave a new dimension to how I work which was more illustrative and did not include quotes or words. Chris created the paintings included in the pieces and the concept, design and organic materials was my contribution to the collaboration. The statement that I wrote for this piece is as follows: I hear the phrase “an act of nature” to describe the devastation caused by floods, tornados, hurricanes and other “natural disasters”. But, are the changes in our weather our interaction with nature. We view nature a force apart from us and struggle against it rather than being a part of it. This piece reflects a hope that we learn to become part of nature rather than be in conflict with it.

Much of your work requires hand sewing can you expand on this?

All of my work is hand sewn. My tools are paring knives, scissors, sewing needles and waxed linen thread. I have used a sewing machine on bull kelp, but I ruined my machine. Hand sewing and using the looping technique is a “signature” style that I have used over the years.

You have exhibited at SOFA (Sculptural Object Functional Art and Design Fair) in Chicago and SOFA, NYC, since 1999 expand on the importance of being able to exhibit there?

It is an International Exposition that over 30,000 art lovers and collectors attend within a 4 day period of time. It is highly competitive between the galleries and the artists that are chosen by the gallery to feature.

Tell us how tickets to The Lion King changed your art practice?

A friend gave my husband and me tickets to the Lion King in New York. As a child, I wanted to be a fashion designer. When I saw the costumes, I thought that costume design was my true calling in life. The next day, we went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and viewed the Papua New Guinea basket masks. It was an epiphany for me to combine both basketmaking and fashion and that is when I decided to make figurative vessels.

How important have you found the need to balance your other life – and your art life?

Both are very important to me. It was more of a struggle when we had a houseful of children. My husband is also an artist so it was about trading off and making equal time for both artist and personal life. It is easier now that we are empty nesters. We schedule time to be together. When you do art, you get wrapped up in it. If we didn’t schedule in personal time, we would probably never see each other.

‘With Child’

Thomas Jefferson has also helped your career; with this paraphrased quote, “the harder I work, the luckier I get” expand on this?

People have often said that I am so lucky to be an artist. I have to agree, but luck really has nothing to do with it. It is many hours and hard work. Nothing glamorous, no luck involved…just passion and hard work.

Contact details.

www.janhopkinsart.blogspot.com

Jan Hopkins, Washington, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2015

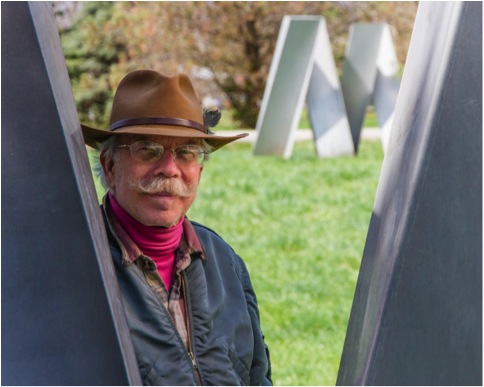

Larry Renzo Lewis

Symbols/Pictographs:

Expand on your use of Symbols/Pictographs/Icons in your work?

I use symbols/pictographs as a secondary means to convey message. Symbols have been around since the beginning. Now after hundreds of years after the introduction of the alphabet, we still depend on symbols for rapid recognition in everyday life – restroom icons, warning signs, on and off function, identification. A form of communication that spans time, culture and language. It seems to fit with the message of my work.

Is there a symbol you use in your work you find more important than others?

Yes, a circle divided into four equal parts or a square separated in the same manner. This was a marking I was using in my work even before I was made aware of its meaning. During the time I was residing in Yelapa, Mexico I was informed by a western person that studied shamanism and by a Huichol shaman. The symbol was used by a group of people in the Amazon in similar fashion as the Ying Yang symbol is used in Asian culture. Instead of being separated in two parts for good/bad or right/wrong, it was separated into four parts referencing good/bad or right/wrong adding time and dimension. I was amazed at this concept. To think a primitive group of folks would consider “dimension and time” in their belief structure.

Closer to our cultural times you have used modern mathematical and physical symbols. Expand on this in relations to your work?

I believe the language of mathematics and physics to be universal. It seems appropriate to include them in my offerings.

Stone:

Closer to our cultural times you have used modern mathematical and physical symbols. Expand on this in relations to your work?

I believe the language of mathematics and physics to be universal. It seems appropriate to include them in my offerings.

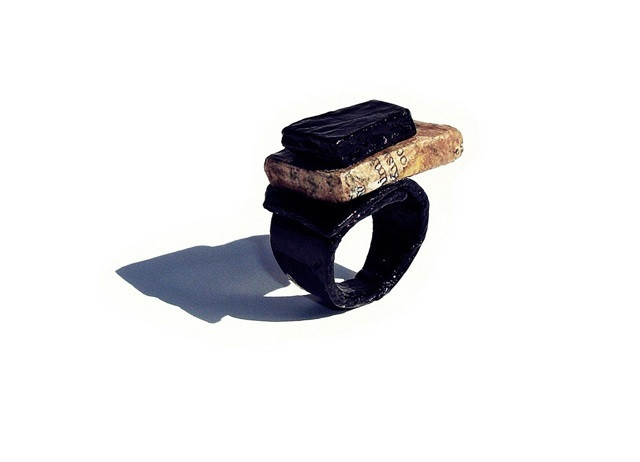

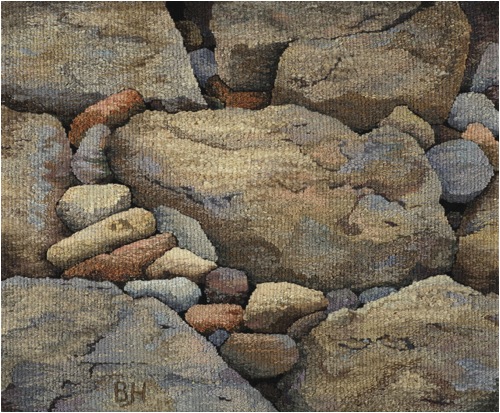

Discuss the way you use stones in your art both sculpture and painting?

I chose stones/rocks because I perceived them to be a most basic element – unpretentious, solid, hard, heavy, of the earth, foundational. I use them as metaphors for thought, memory and emotion. In doing so, I can offer a physical presence to that which is intangible.

.

Discuss your comment “Everything is connected”

Wrapped around stones, stones bound together, wrapped around the wrists and ankles of my figures, and figures bound together. I do this as a representation of my belief – “Everything is connected.” All things in our known universe share fundamental common bonds. In my work I bring this to light by the representation of physical binding.

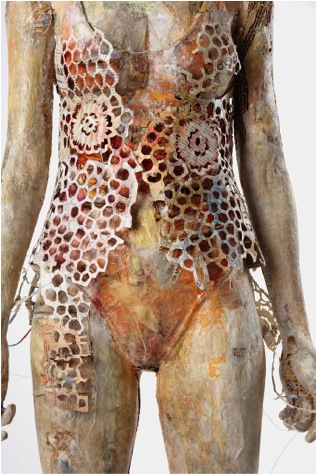

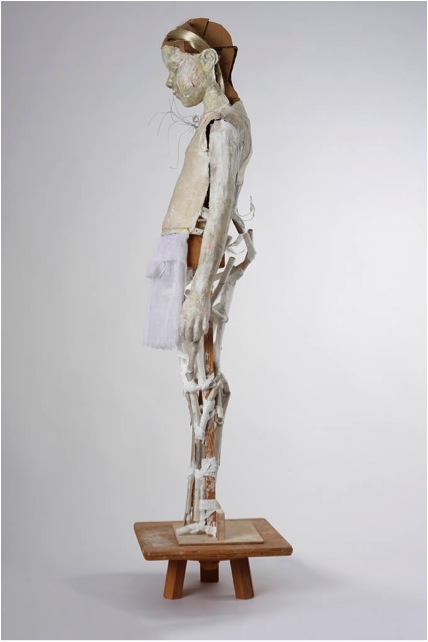

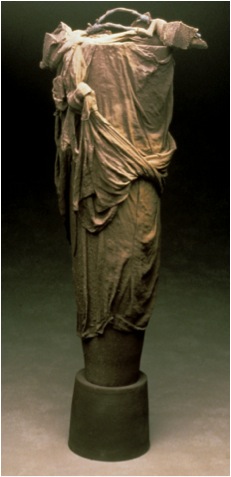

‘An Emotional Partially Obscured’

Nudity:

Clothing gives a historical point, therefore why is Nudity so critical to your work?

Clothing / adornment makes a statement of not only historical but social, cultural and even religious status. I wish to make statement void of these elements, poignant only to humankind as one.

‘Balancing Nature’

Masks:

Explain the importance of masks in your work?

In my life experience, I’ve found that everyone I have come into contact with at some point in time has put forth a facade. Whether camouflage or deception, I find this to be a practiced human trait. Just one of the many things that separates us from being mistaken for lawn chairs.

Your late wife studied archaeology and anthropology how has this effected your work?

I perceive the effect slightly. Accompanying her on a few digs. It simply added support to my thoughts, seeing artifacts unearthed which held meaning of a prior time while offering importance of a time in the future.

‘Adrift with my Memories’

There are many similarities in very different cultures. You have lived with indigenous people; discuss how this has influenced your work?

I agree with your previous statement and believe that when one experiences a different culture it enhances their ability to better perceive their own culture. I would hope the influence is apparent when viewing my work.

How do you decide on making a work into a painting or sculpture?

In my youth I was privy to a quote from Ansel Adams – “there is nothing worse than a brilliant image of a fuzzy concept.” I approach all my work in the same manner. Conceive the concept, develop and complete.

Do you use the same subject in both mediums?

If you are referring to subject matter “Yes.” Subject in regard to models “No,” with painting I use models. Regarding sculpting, I rely on sketches and or composites.

‘Neo – vision’

Your own strict religious upbringing, how has it influenced your life and work?

Wow, big question! To this day, I am still attempting to sort that issue out. I have come to view organized religion with ill repute. I live and work in accordance with the content of my character and the faith that there exists something greater than I, and greater than my understanding, that fuels the cosmos.

‘Emotional Temptation’

Contact details.

Renzo aka Larry Lewis

rockbound666@gmail.com

Represented by – Masterpiece Publishing Inc.

www.masterpiecepublishing.com www.winnslavin.com

Larry Renzo Lewis, Nevada, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, March, 2015

Miki Kubo

Miki Kubo, Japanese Artist in Australia photograph by Henry Rust

Miki Kubo, Japanese Artist in Australia photograph by Henry Rust

Zoneone Arts is delighted to bring Miki Kubo to you…

You take great inspiration form nature please discuss this?

When I look at Nature, at Life, I see a purity and connectedness that I long to be part of again. I feel that I am out of it, and I yearn to with my true self, my song. I want to feel the harmony with life that I see there. I want to cut through the noise to have a direct experience of the music of life.

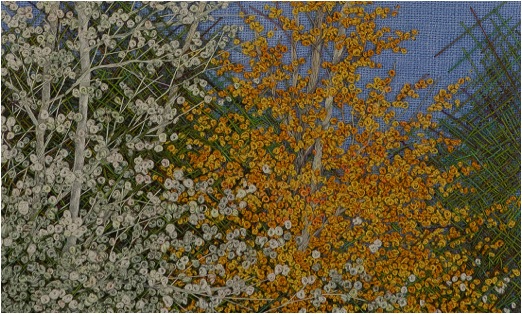

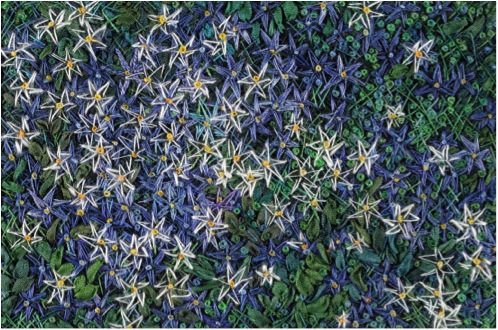

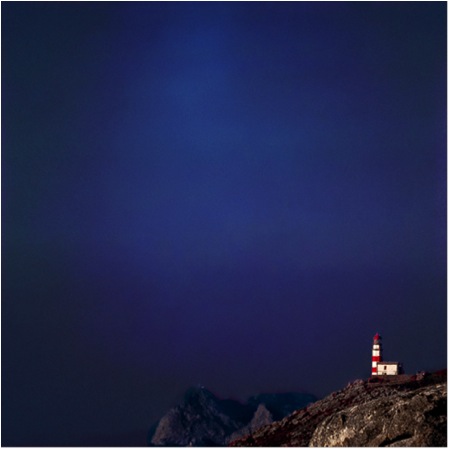

‘Cosmos’ photograph by Henry Rust

Does your Japanese background give you a different connection with nature and animals to the one you have developed since arriving in Australia?

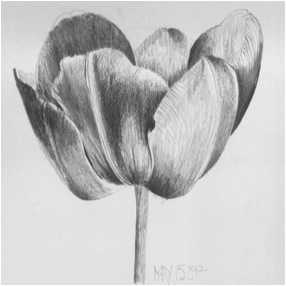

This is a question I am asked all the time as a Japanese artist living in Australia. I feel that my attitude as an artist and the fundamental approach to my subjects were formed and cultivated in my early teenage years in Japan. It might sound strange to Westerners, but we are encourage to be Westernized in so many ways especially after WWII. Many famous Western literatures are translated in Japanese and have been published repeatedly for children and adults, and J.D.Salinger was one of them. His book “Franny and Zooey” - it has guided me to be an artist who practice “see the subject for exactly what it is” and focus on “An artist’s only concern is to shoot for some kind of perfection, and on his own terms, not anyone else’s.” in my work. After school, I devoted all my time doing pencil drawings on white Canson paper…not much homework was done.

Animals you meet in Sydney tend to be more impudent and brave than the ones you come across in Japan. Australian sunlight is much brighter, which produces plenty of flowers in all seasons and trees seems to be much happier, but short lived. There are much more opportunities for me to study Animals in Australia and people’s passion for nature appears to be much stronger and direct. Being in the unfamiliar, forces me to focus in more strongly and recognise the subject.

Discuss your use of Australian flora and fauna in your work?

‘Sugar Glider’ photograph by Henry Rust

Australian flora and fauna designs were my engraving teacher Anne Dybka’s forte. When she closed her studio business due to her age and eye illness, she had introduced me to her distributers. During my engraving training with Anne, she made sure that I was able to engrave Australian flora and fauna in my interpretation so that I could carry out her legacy.

How important is the engraving (or carving) aspect of your glass art in your current work?

Engraving requires great focus and is extremely important in my artwork. Mistakes can’t be erased. The spinning bit demands deep concentration. Ear-muffs reduce outside distractions. Constantly running water means that I can’t see the surface where marks are being made.I trust in my connection with the subject and in the engraving process and focus goes deeper and deeper, allowing the work to come into existence.

Engraving on glass brings three dimensions, and the play of light and shadow, to the work. This is what makes it so appropriate as a medium for representing life. Each motif is its own self. I can’t own, or possess it, or take it away from what it is meant to be. All I can do is honour and wonder at its perfection. I do this through glass engraving.

‘Kookaburra’ photograph by Henry Rust

How you would like to see the pieces used?

My work is done in homage to the Life Force. In making a piece I touch the core of me – I reveal what I worship, who I am and what I aspire to be. I hope that through my work, others can find some of the peace, truth and joy that I find there.

Pieces that are culturally very different are your Hair Decoration Series can you expand on this series?

‘Small tiara with Phoenixes’ photograph by Henry Rust

This series is inspired by the “Chinese Kingfisher Hair Dress” from the Qing dynasty. I wanted to speak about the ’Power of Object’ through this series. I believe the original Kingfisher Hair Dress crowns were rented to decorate many young Chinese brides who were about to meet their unknown husbands under their arranged marriages. There was a time that tradition and family ties had so much power over people’s lives, so much in fact that there was no space for an individual’s feelings. Although we might have more freedoms now, compare to their past, we can still relate to those people who had to perform their act as what they were expected to. Otherwise we wouldn’t say “the show must go on” and drink from a cup that says, “Keep calm and carry on”.

‘Three teeth comb’ photograph by Henry Rust

On slightly larger piece in this series is ‘Bees and Flowers’ head dress discuss this piece?

‘Bees and Flowers, Head dress photography by Henry Rust

This particular headdress was dedicated to an Australian woman I saw in Queensland, we were at her late partner’s funeral ceremony. She was stood straight during the entire ceremony, wearing a golden eucalyptus flower branch on her hair.

Colour is so important to glass artist work tell us about your passion for colour?

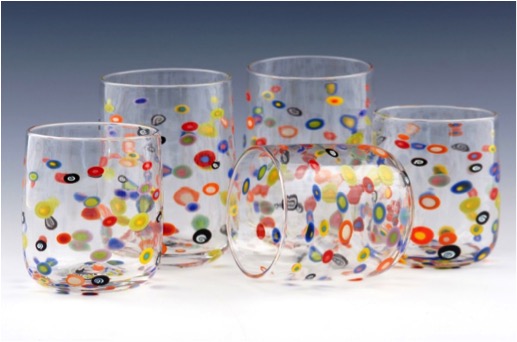

I started my glass practice in a small glass-blowing company in Japan, in which we manufactured our own glass colours. Mixing glass colour from sand involves serious calculation based on chemistry and heat expansion technology. We had to sync the expansion rate and shrinkage in every colour so that the glass was compatible. It was time consuming, temperamental and an expensive process, and usually the recipes were kept in secret by the colour engineer in the same company. Therefore we had a very limited colour palette - red, orange and yellow were extremely rare to us. In Australia, usually the colours (for glass-blowing) come from New Zealand. Their colour ranges are - as many as nail polish, transparent and opaque in both! Now all the subtle colours in glass are accessible to me in Sydney.

‘Siamese Fighting Fish’ photograph by Henry Rust

However, as much as I love coloured glass, I enjoy working with non-colour and plain clear glass. It has its own attraction in that the engraved surface displays a much fine grade in shadow.

‘Frog and Orchards ‘photograph by Henry Rust

Shapes is predominate in your work, discuss shape in relationship to the piece, ‘Goldfish’?

The composition of glass is in its liquid form not solid - in the state of not hot enough to move, or it is moving but too slow to see. In this reason I like watery motives to go with glass and goldfish are on of them. Goldfish are man modified creature from many generations of mutated Crucian Carp which cannot exist in wild. It needs special, human controlled environment to survive. I’d like to keep them in safe bubble shape so that we can study their tranquility.

‘Goldfish’, aqua photograph by Henry Rust

Your piece ‘sea Dragons’ can you explain where you study the shapes and details of the animals you use?

I had a plastic Sea Dragon toy that I was hoping to use as a reference for a particular engraving, however it didn’t do justice to live Sea Dragons. I am very fortunate to be able to visit wild parks or aquariums as part of my job, to observe animals. At the Sydney Aquarium in particular - there were only ‘Weedy Sea Dragons’ exhibited at that time, but now you can meet ‘Weedy Sea Dragons’ and ‘Leafy Sea Dragons’ both at the Aquarium. When I engrave an animal, it is a portrait of that animal. It is not ‘a Sea Dragon’, it is that specific, personal Sea Dragon. Every individual animal is its own spirit. Each piece I make is an individual portrait of that animal, of that spirit.

‘Weedy Sea Dragons’ detail, photograph by Henry Rust

‘Weedy Sea Dragons’ detail, photograph by Henry Rust

Fragility is part of your work explain how important the openings are and how what is missing is such an important part of the whole?

Nature does not like to be disturbed. Pretty much everything we touch, we destroy.We break the perfect balance of nature and call them fragile.

In terms of my Glass bubble openings and why I like to design the edges into the motif’s - it is purely for the form of the Artwork - the carved glass edge adds light to the engraving and pushes the engraving out at the viewer. Also I get toapply two different kinds of engraving technique in one subject - intaglio engraving to carve in the motif and relief engraving to carve out. It is not about what is missing - it is more about emphasizing what is there.

Can you expand on the time you spent with Anne Dybka and how this time to influence your work today?

Between the year 2003 and 2005, every Saturday morning I was at Anne’s studio on Argyle Street in The Rocks. The lesson went usually two hours, it start off with me explaining to Anne what motif I will engrave and how I will approach it. The rest of the class we just talked about animals we both related to. There weren’t many things in common between us, but the strong feeling toward animals that really connected to us, was solid. She was an animal activist, born Greenie. Once she expressed me how she felt about Japanese whaling.

As her field of vision got smaller and darker, she shared many stories of her life to me.The job she had during the War in England, the big farm house she had lived, her passion about horses, her children’s toy stories, the egg fight her children and neighbour’s kids caused, her boarding school time in Switzerland, about the after-life,and about her mother. I was extremely fortunate to be able to spend time in her studio, she had shown me her affection to nature, her joyful and rich world through her work. When I engrave glass, I constantly imagine what Anne would do and what she would say.

Cameo work is very time consuming explain this method and how you use it?

Imagine an apple, a gorgeous red skin apple. When you peel the red skin, you find white fruit under it. To make a cameo piece, you will need a glass just like an apple. One colour on top of another, and sometimes triple layered glass. Usually, the skin- the first layer colour will be the motif you leave out. You carve the background area in order to make the motif lift up. This carving technique for cameo is called relief engraving. My Cameo bowls are interpretation of traditional hand-painted Porcelain in Asia.

‘Crab’ Cameo detail photograph by Greg Piper

You are a member of the Guild of Glass Engravers UK, what has been the value of a worldwide membership to you?

My initial reason for joining the GOGE was to follow the footstep of Anne - she was delighted when she heard the news I have been excepted to be a member. The GOGE offers vast information in engraving to all the public, promote artists and hold annual guild exhibitions. By being a member, it will gives you a great opportunity to connect with glass engravers worldwide. They hold assessment once a year by request and help you with developing your engrave practice. I found them very supportive, encouraging and full of warmth.

You have your work documented and photographed, discuss why and how this is done and why you would recommend this to other artists?

For many practical reasons, documentation of each piece is necessary for the artists who work with galleries under a consignment basis. Not just the detail of your work, the information such as, which gallery is selling it, for how much and how long. If I know who has bought it, I will record that too. Also when I take commission, having the list of previous pieces I worked on helps to come up with a fair quote for the future piece. Personally, engraving is a very intimate process. I spend at least few days extending my awareness towards the subject as best I can, so it feels like my mind is fused into the subject within the glass. Sending a finished work to the photographer is an important ritual, give a proper cleaning to the piece and pack in a box. It is the time that telling myself I am finished with this work, the piece is now ready for everyone’s interpretations and experiences.

Can you tell us about your work studio?

Being a Japanese Artist in Australia and travelling a lot has given me the privilege of working with many fine Sydney Glass Artists and sharing their work Studios. I have also worked in Sunshine Coast, Adelaide, Perth and Canberra Studios often as well. As I travel a lot, I usually take my portable Glass engraving table set up that I constructed, so I am able to do my engraving anywhere.

‘Goldfish’ cameo photograph by Henry Rust

What is your advice to Collectors of glass?

When I was in a glass company in Japan, our retail manager who sold our glass use to say “I don’t need to know the difficulty of glass technique, what I need, is the eyes that can tell what appeals to customers and the experience to know how much people will pay for it”. she was in charge of pricing all our work. I can only half agree to that! I do not wish my work to be defined and evaluated only by its technicality although I admit it is fascinating to know how the work was made. I imagine everyone has their own motivation and passion to collect objects. To collect something you will usually do some investigation in the field. What I do is a hand-made artwork, not machine made mass-production. Handmade art reflects the heart and soul of the artist. This is my best advice to a collector.

Contact details

www.mikikubo.com

Miki Kubo, Japanese Artist in Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, March, 2015

Mariolina Mascarino

Can you discuss your thoughts on the overlapping of design and fashion in your work?

In my mind design and fashion are true art forms which are worth taking into consideration especially when it comes to jewellery and body adornment. Also, I think of my jewellery as something which is always evolving and changing together with the new trends.

When I start working on a piece I always need to have clear in my mind that what I’m going to make is not only art but also, and above all, a jewel. Here is where the need of making something that fits into the fashion trends overlaps the need of expressing myself as an artist. What I want to do is to make something unique but comfortable and wearable as well.

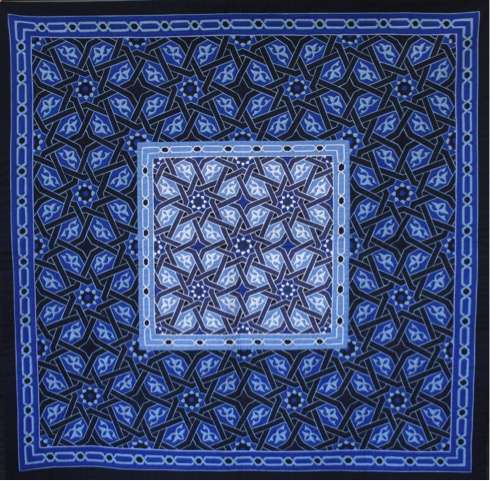

Colour is very important to your work. Can you discuss this?

The use of colour plays an important role in my work. I believe that colour gives personality to a piece or, better yet, it “makes” the piece. I am happy to work with paper because I have so many shades and colours to choose from, also I never run out of newspaper pages with words and pictures on them which help me to achieve even more unique results. Often, when I can’t find the color I have in mind, I paint the pieces myself, using water based paints and mixing colors together. In those cases, I’ll always end up with a special shade, which I will not be able to create again and this also contributes to the uniqueness of the piece.

Compare two pieces of your jewellery showing both glamour and simplicity, and the need for both in your collections?

I’d like to compare a glamorous necklace like the “charcoal and gold chain” with a more simple one called “corolla”. They are two completely different pieces: the first one designed to be worn at night or on special occasions, while the second one, with its minimal, fresh style, is perfect for everyday wear.

'charcoal and gold chain’

charcoal and gold chain: kraft paper, painted newspaper scraps, crocheted cotton yarn, cardstock. Water based paints and glues. Colors: charcoal, gold. Total length: 130 cm – 51.2 in.

corolla: crepe paper, waxed cotton cord, water based protective varnish and glues. Approx dimensions: around neck 46 cm – 18.1 in, total length: 51 cm – 20.1 in.

Corolla

Having both simplicity and glamour in my collections is not only a need but a choice. I like to offer a woman the opportunity to always be herself, following her personal style. I want her to feel, free to wear accessories the way she prefers, choosing simplicity or glamour according to the mood or the occasions. In other words, I want her to be unique in every moment and with every outfit.

Why have you chosen to use paper as your main medium?

Paper is interesting in many ways and it allows me to express myself at my best. Not only is it an environmentally friendly medium, which can be easily recycled, but it is also extremely versatile and shapeable according to my needs. Working with paper of all types (crepe and tissue paper, cardboard, cardstock, kraft paper…)