Lisa Cahill

What lead you to glass making?

A love of design let me to Glassmaking. I never even considered Glass as a medium until I chanced upon it at an open day at the School of Art in Canberra. I had always imagined I would be a painter or a jewellery designer but as soon as I realised I could learn how to manipulate glass to make my artworks I was hooked.

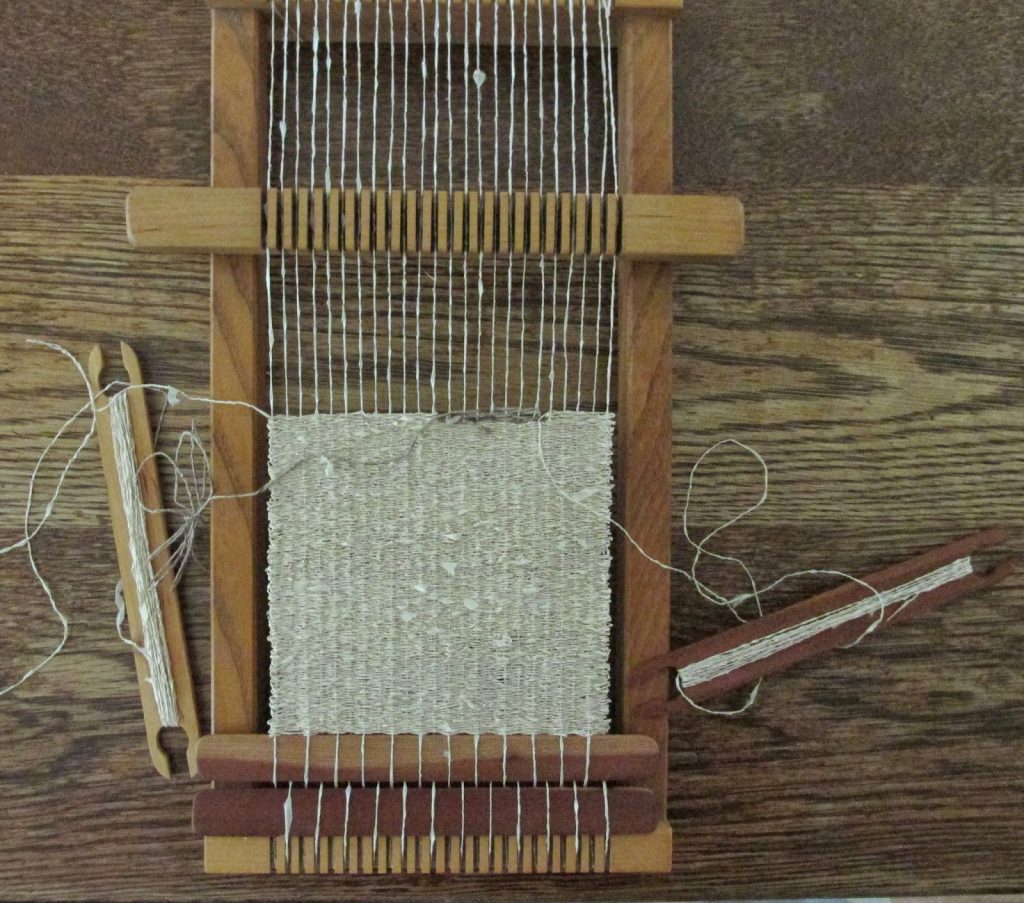

You work with a variety of glass techniques, etching, engraving, lathe work and carving through opaque and transparent layers. Can you give us an image that shows each technique and a very brief explanation of the technique?

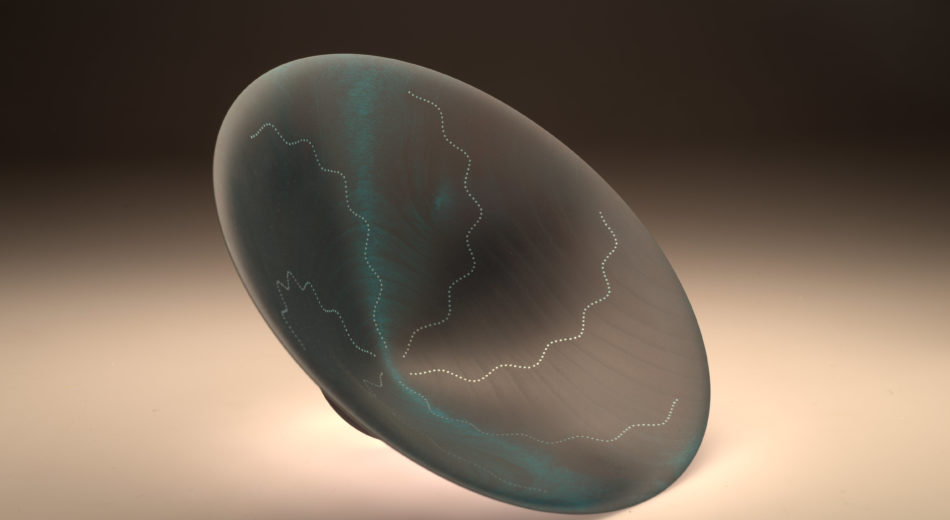

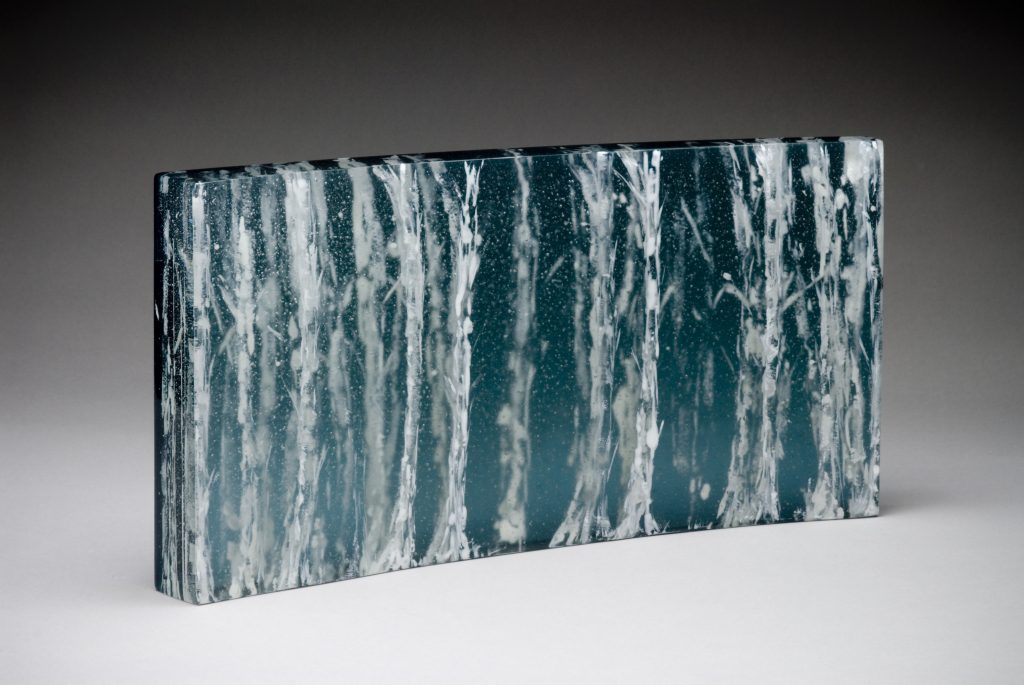

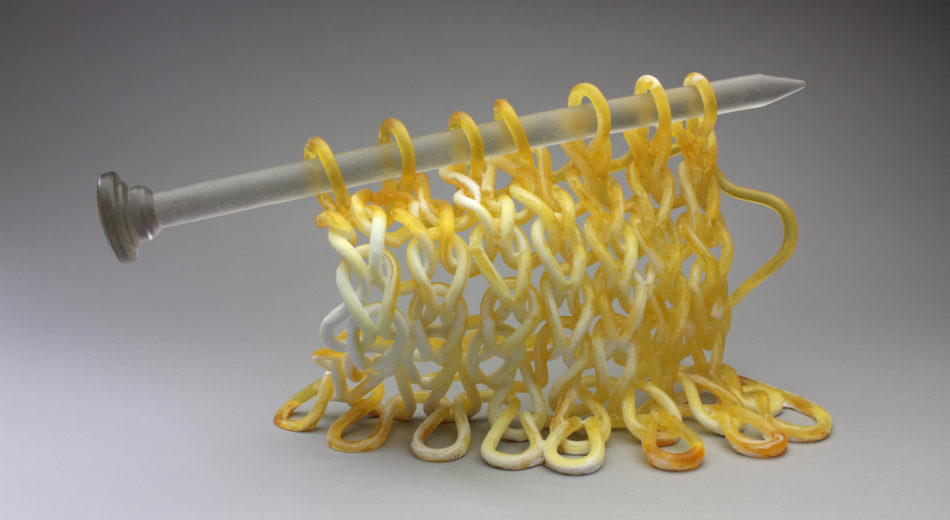

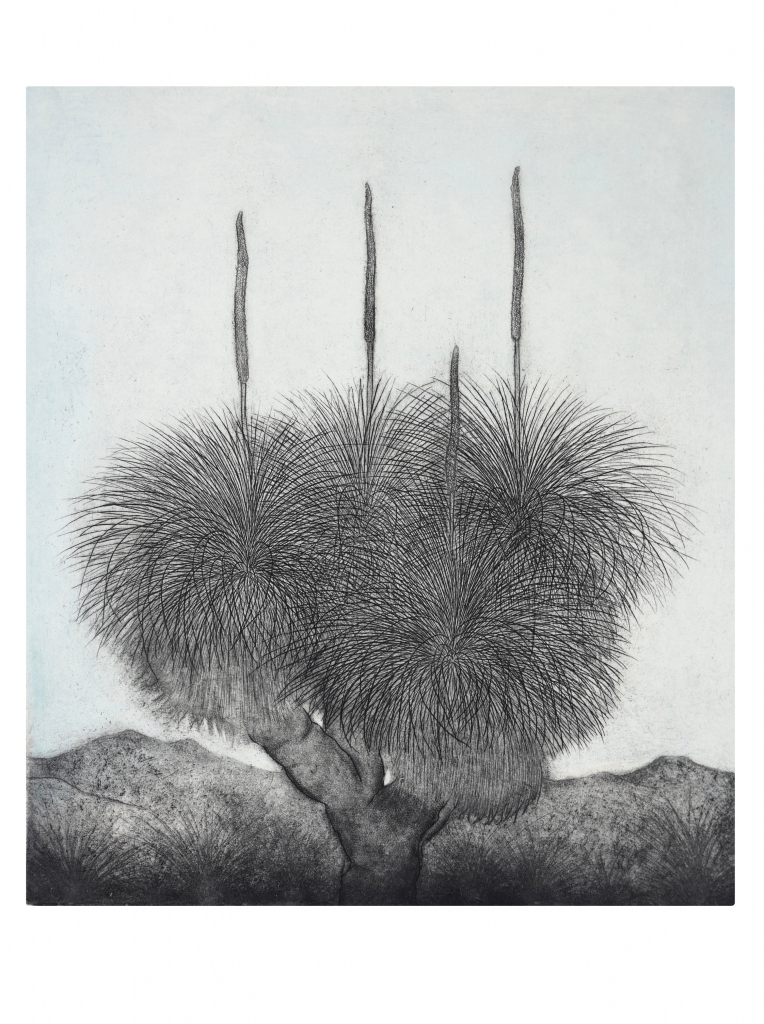

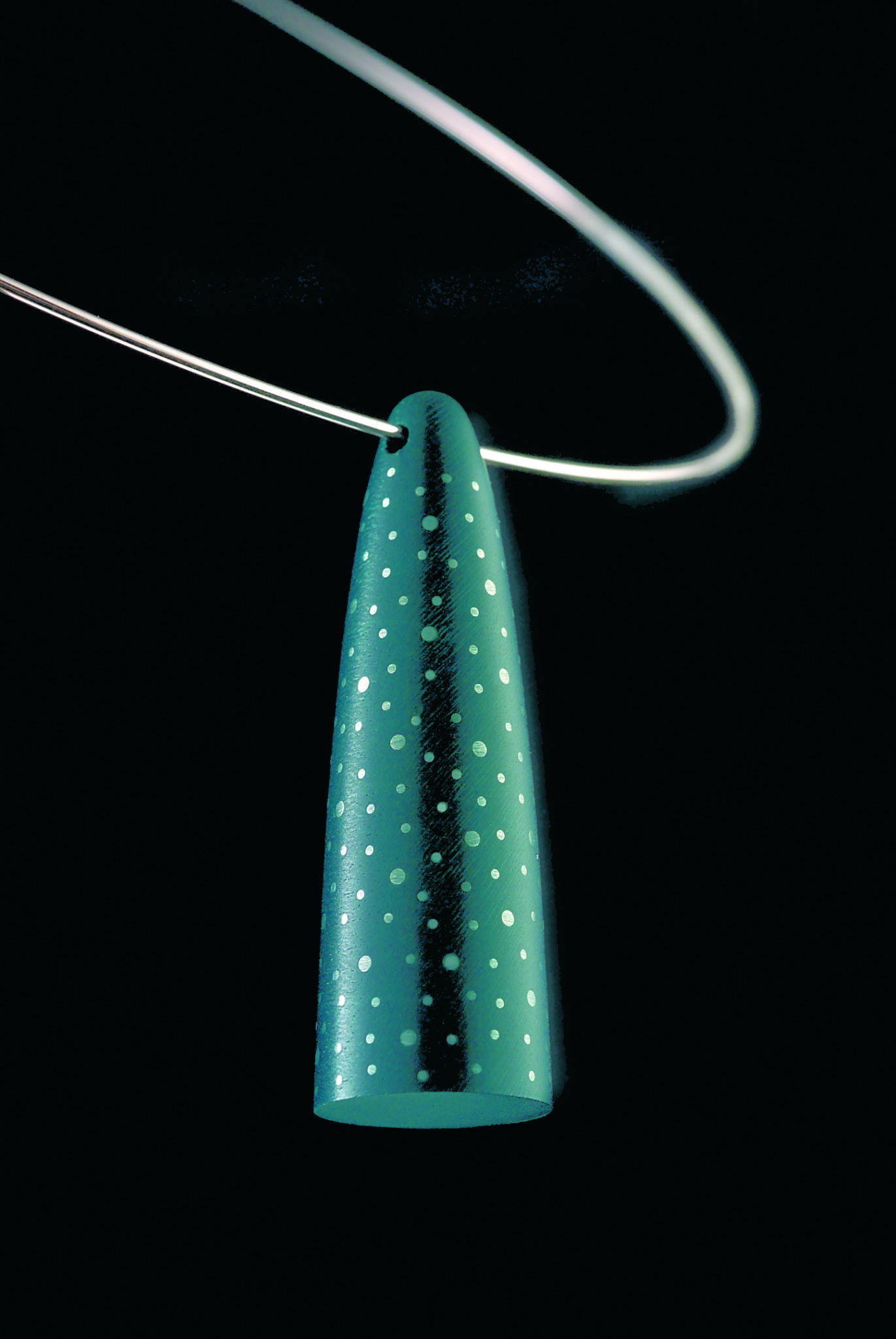

In “Virga #2” 2014 kiln formed and carved glass 28 x 48 x 6 cm Photo Greg Piper

I used the disc grinder to carve through an opaque layer of glass to reveal the transparent colour beneath.

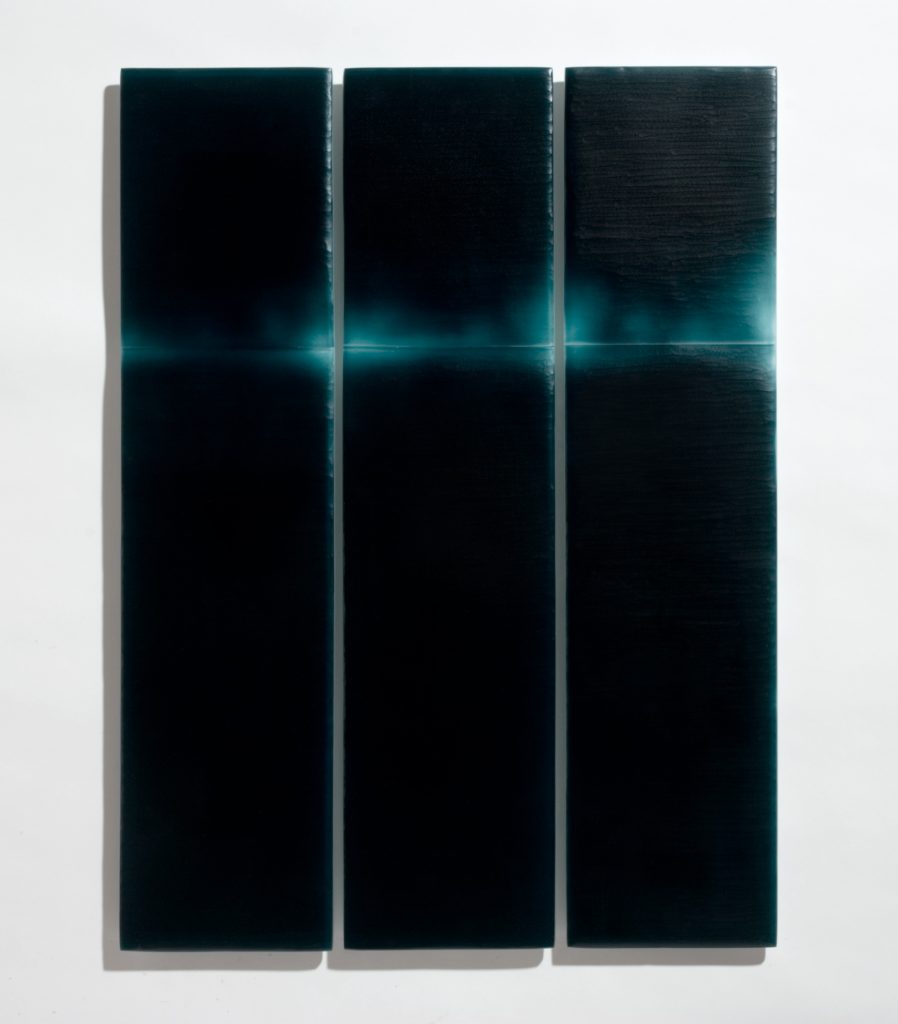

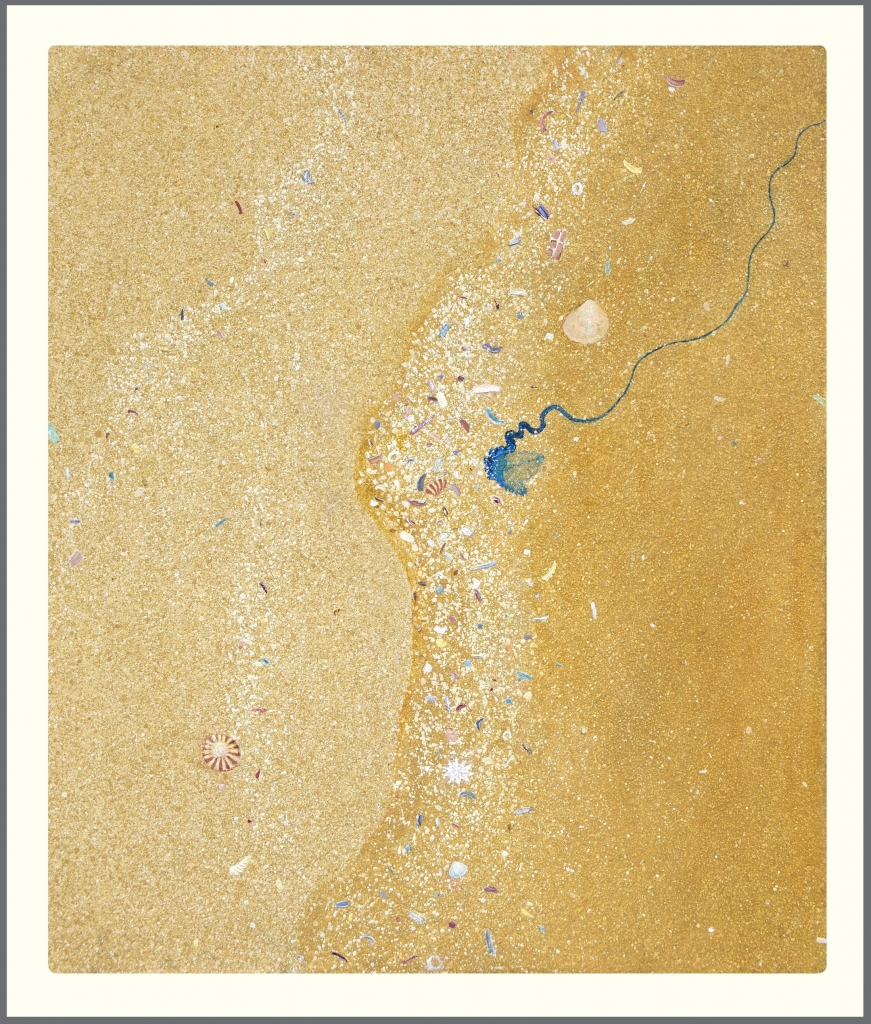

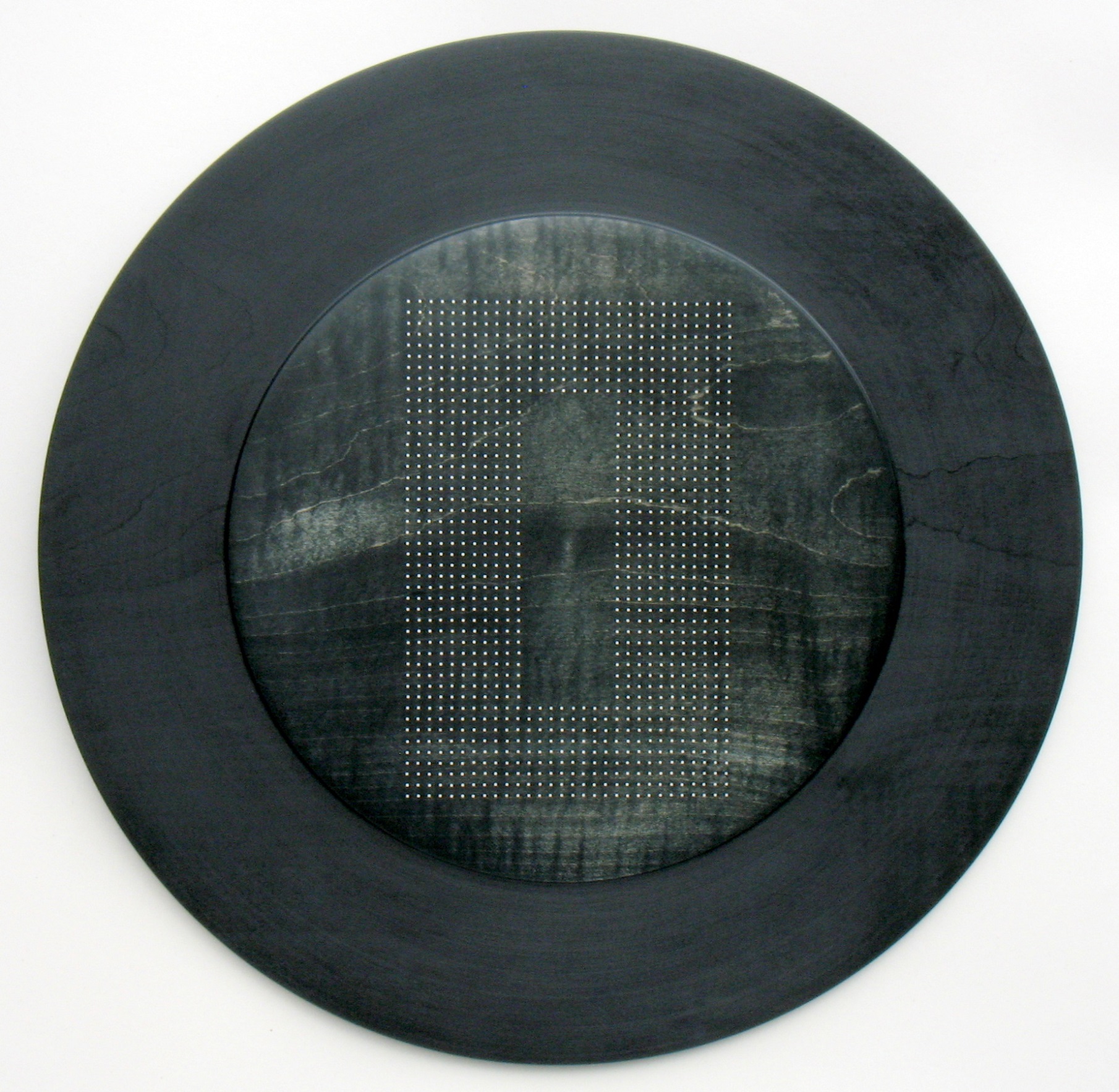

Catching Light #4, Kiln formed and wheel carved Glass, 67.5 x 50 x 1 cm, Photo Greg Piper

In I used a lathe to carve through the transparent layer.

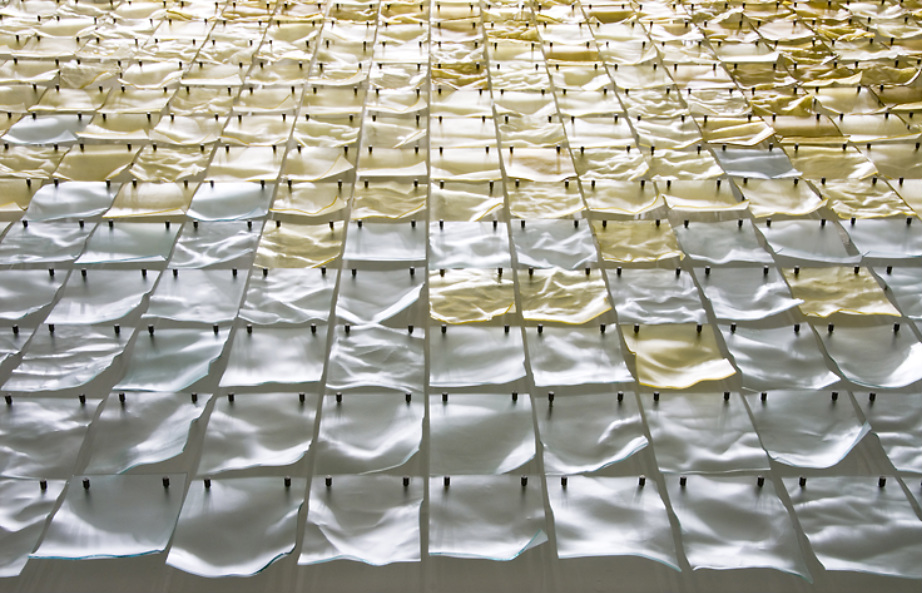

Can you expand on your large, 36 sq. metre art work made up of 1000 postcards?

“Breathe” was a commissioned for a complete refurbishment of a corporate building at 151 Castlereagh St in the Sydney CBD. It is 6.6m high and 6.6m wide and sits out from the wall 10cm.

The architects asked me to put in a design proposal for a large artwork for an internal void. I was making very labour intensive work at the time so it took some time to come up with a design that could be produced on large scale. I wanted to be able to make the work in components that I could produce in my kilns and were easy to install. I also had to work within a budget which meant that the work I was doing at the time, layers of fused glass that was then carved back, the materials alone would have wiped out the budget. I scaled the work back and thought on a more simplified way what I could achieve the same aesthetic that would have an impact on a large scale.

I made a small maquette of a carved glass landscape and used it as the inspiration for the larger work.

Each piece has been cut, polished and then slumped in custom moulds in the kiln to take on the shape of crumpled paper. The graduating shades of amber were designed to be evocative of a fading sunset inspired by he location of the building in the Sydney CBD, known for its beautiful harbour and stunning beaches. The individual glass panels were to appear to be paper blowing in the wind. I used around 100 moulds to create 1250 panels. The whole project from conception to installation took several years but the actual making of the work took 6 months to make and 1 week to install.

Undercurrents, 2018. Kiln formed glass, stainless steel, aluminium backing board. 1590 h x 2260 x 100mm deep. Photo Greg Piper

Discuss your work in relation to collaboration with other artists.

I can’t say I have really done a lot of collaboration as such. I have fabricated artwork for other artists and I have had artists fabricate components of my artworks. I think it’s very important to acknowledge the difference. I believe when collaborating you should both be involved in the design and concept stage. In a fabrication/gaffer situation one person with specific skills is fabricating another artists design. I have enjoyed being in both roles and am always very grateful that I have so many talented artists around me that I can draw upon to realise an artwork. I would love to do collaborations in the future.

How has the Danish landscape influenced your work?

Definitely, the cold winter landscape has had a very big impact on me. Being exposed to the Danish landscape from a young age has made me acutely aware of the contrasting Australian landscape and my connection to it. The Danish winter landscape was a big influence in my early works but more recently I have been very drawn to light and landscape and the mountainous landscape around Canberra.

Between the woods and Frozen Lake 2011 Photo Greg Piper

How has the Australian landscape influenced your work?

‘Beneath the escarpment’ my most recent body of work was inspired by the Illawarra Escarpment which I often visit.

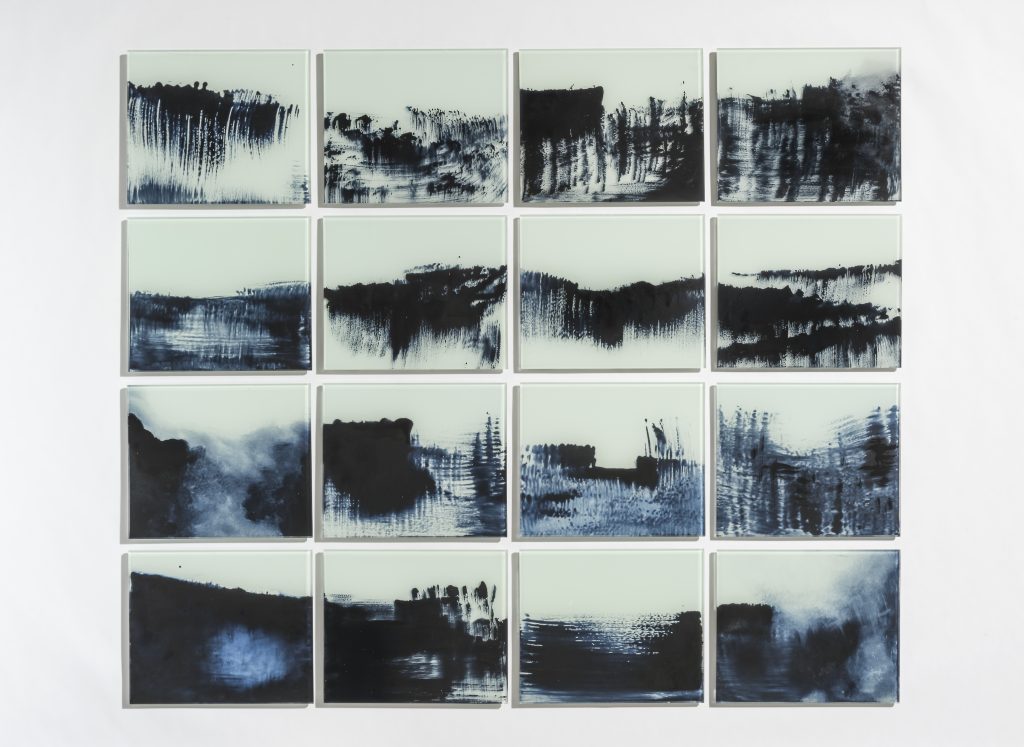

Beneath the Escarpment, 2018, kiln formed and enamelled glass - set of 16 wall panels, 1100 h x 1300 w x 10mm Photo Greg Piper

Can you explain your close association with the Canberra Glassworks?

I have been involved with the Glassworks since it opened in 2007. I have stocked the retail outlet since it opened and have been a regular hirer, exhibited regularly in the Gallery and have had several artist residencies there including a twelve month fellowship that I will begin this July. Since I moved to Canberra in 2011 I have been an active member of the Canberra Glass Community and the Glassworks is a great hub for this community. I have just returned from installing a commission I completed for the Sir John Monash Centre in Villers-Bretonneux in France that was commissioned by the Department of Veterans Affairs through the Canberra Glassworks.

Expand on your most current commission for the Sir John Monash Centre?

Where is the centre?

The centre is behind the Australian Memorial in Villers- Bretonneux, North of Paris, France. Designed to sit behind the Memorial it has been dug into the earth to resemble a war time bunker and not overshadow the existing memorial.

Why is it there?

The Centre has been built to commemorate the 100 Centenary of the end of the first world war. The original memorial was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in 1935 to commemorate the 300,000 Australians that served and the 46,000 that lost their lives on the Western Front in World War I.

Discuss the importance of the centre and when it will be opened?

The Sir John Monash Centre is a museum and interpretive research centre that commemorates the Australian Servicemen and woman who served on the Western Front during the First World War. It was officially opened on the 24th of April 2018 by the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. Through interactive media installations the centre tells the story of Australia before the war, why we went to war, what we achieved and how being involved in the War changed Australia.

Photo Tim Wiliams, Architect

The design and scope of the centre? The building was designed by Cox Architecture with Williams, Abrahams and Lampros. Photo Tim Wiliams, Architect

Costing $100 Million dollars, The, one thousand square metre centre is designed to be "subservient" to the war memorial and has been described by one of the architects, Joe Agius, as "almost an anti-building, connected to the monument from an abstract and geometric point of view".

Your input into the Centre?

I was commissioned to make a Glass rising Sun inspired by the ANZAC emblem. The Sculpture sits in a 4 meters high Bronze totem as you exit the building creating a beacon of light drawing you out after the harrowing and moving experience inside.

What and for who did the commission come from?

The DVA enrolled the Canberra Glassworks to put out a national call for artists to submit proposals to make a Glass Rising Sun inspired by the ANZAC emblem.

Photo Tim Wiliams, Architect

How structured was the commission?

The brief was very structured in that it had to clearly resemble the Rising sun Symbol designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens on the Tower of the Memorial. They wished for the artwork to be made of glass but the final design, what type of glass and techniques used were entirely up to the Artist.

Discuss the importance of the Rising Sun to Australians and the world?

The original Anzac badge used upturned bayonets to create a symbol that would come to represent the spirt of Anzac (the Australian and New Zealand Army Corp). Travelling to the other side of the world these diggers had a sense of camaraderie and commitment that helped them battle through rough conditions and unknown territory.

How important are Government Departments to the careers of Australian contemporary Artists?

Commissions like this one can be very important to the careers of Australian artists. It is also important for them to support our creative community as it is through art, design and architecture, music and literature that our story is told. Years into the future these artworks, plays and novels will tell the story of our time. Government departments have an obligation to enable that story whenever possible. Commissions like these also create exposure for artists to connect with a wider audience and one that you would not normally have exposure to. And they can also expand the public’s appreciation of new forms of artistic expression.

Not everyone can commission or buy big, discuss some of your small pieces?

I have always made a production line of bowls, plates and jewellery to supplement my arts practice. I enjoy making the smaller works as it is less labour intensive due to the scale but also allows me to have fun and experiment with aesthetic alone rather than getting caught up with the conceptual side so much. I also love that I can make a product that is affordable and I can connect with people through this work that might not have room in their homes or funds to purchase my exhibition works.

Plate and Spoons, Photo Greg Piper

What is your opinion on the importance of beautiful hand-made pieces in the home?

I have always appreciated handmade pieces in my home as they have always given me joy. Even more so when I have known the maker and know the work that has gone into that piece and that my purchase has helped them to keep making more beautiful work. Having handmade work in your home has a more genuine feel and creates a more personal space. Buying local handmade work enables you to contribute to sustaining your creative community.

Contact details:

Lisa Cahill

lisa@lisacahill.com

Lisa Cahill, Canberra, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May 2018

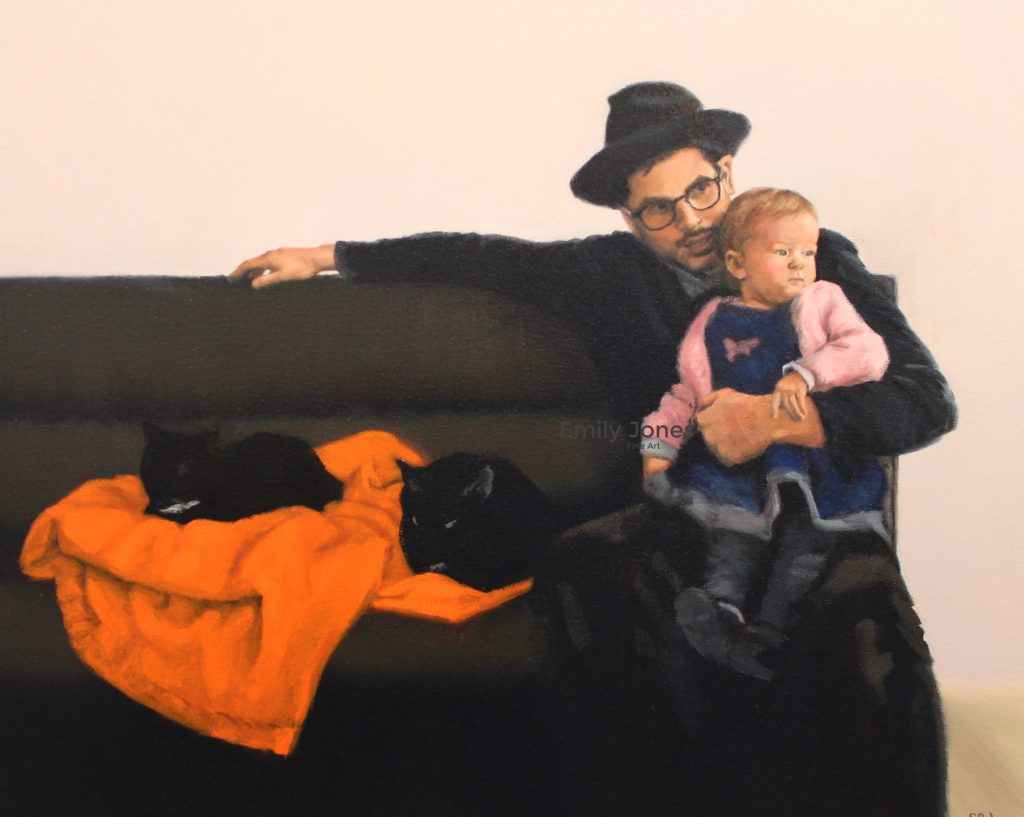

Joseph Genova

How does your connections to Italy influence your art?

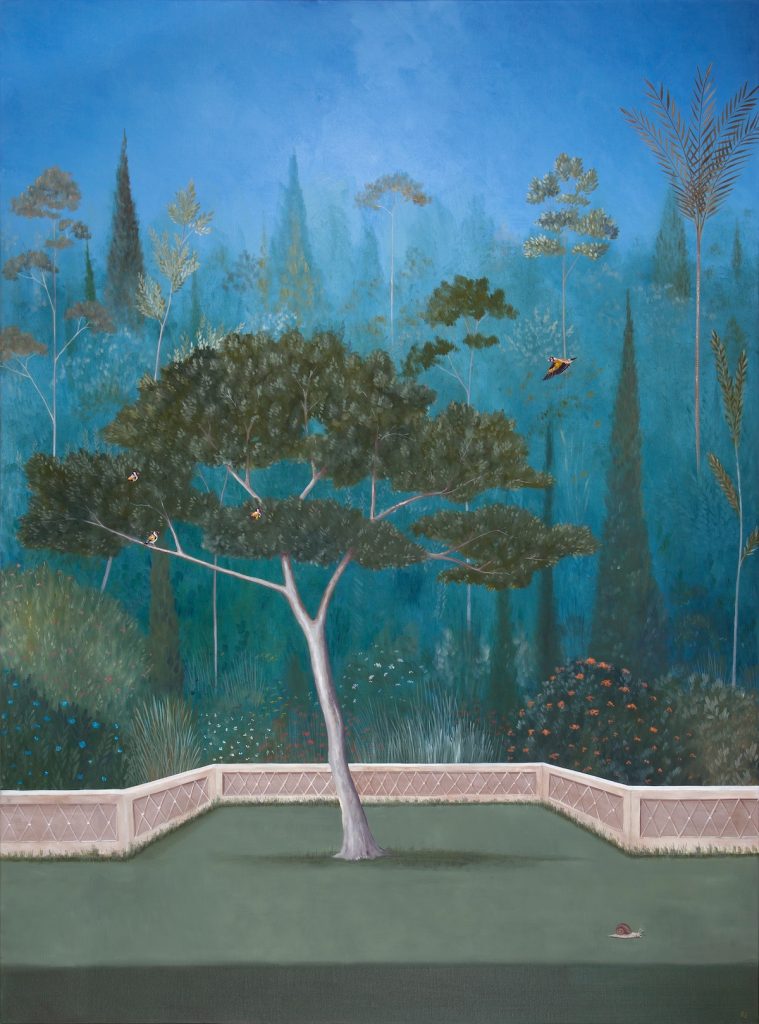

Ever since I was a little boy in Italy, art took centre stage in my life. I was attracted to the paintings, murals, and statues that are abundant in churches and palaces.

I began drawing at an early age and continued when my family immigrated to the US. I longed to be an artist ever since I can remember.

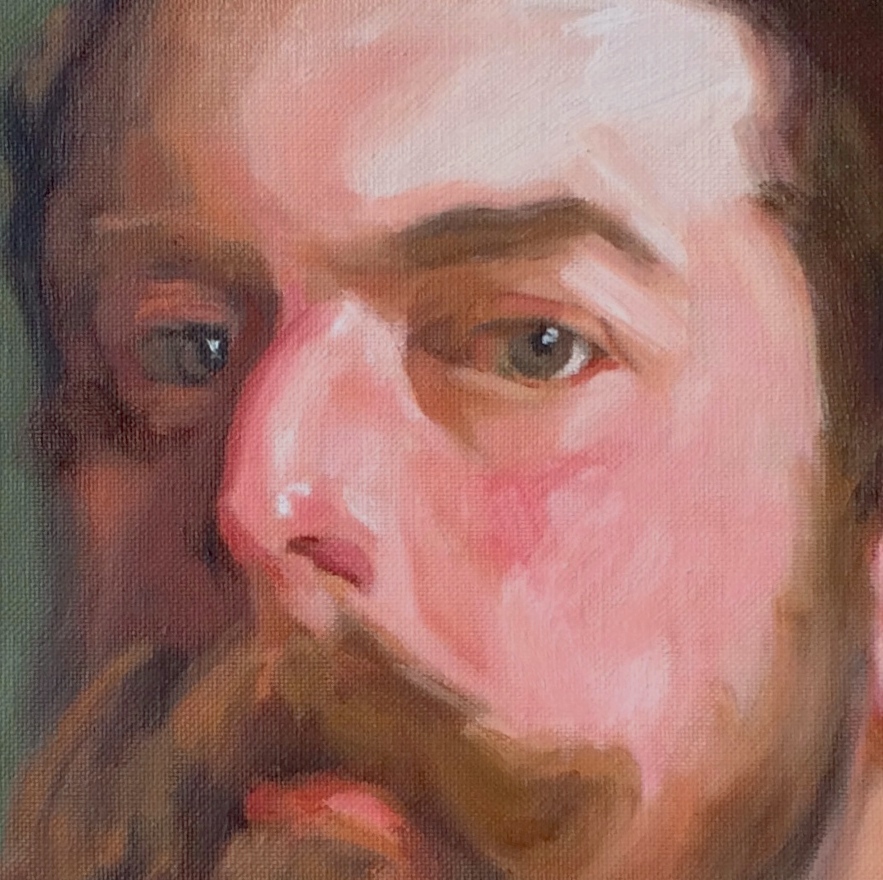

Discuss the inspiration you take from the 17th Century artist Michelangelo Caravaggio?

My first exposure to the paintings of Caravaggio was when I was about 10 years old. I was in a public library looking through an art book on the Italian Renaissance. When I turned a page and saw Caravaggio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” I literally froze. I had never seen a painting like that before, with its dramatic theatrical lighting, bold colours and composition. I decide then that I wanted to paint like Caravaggio.

Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew

Apart from your Italian background how does your current New York life effect your art?

Living in New York has exposed me to all manner and styles of art. If something is new and different, you’ll see it first in New York.

The city gives an artist a holistic perspective, which forces you to compare your art to what’s new and popular in the market place.

You paint fabric, discuss where you source the fabric and what draws you to each piece?

I started painting fabrics about two years ago. Since today’s market is going more and more modern, I wanted to find a way to be more modern while still, remaining representational.

The colour, texture, and pattern of the fabrics is what draws me to each piece. I spend a lot of time arranging a piece of fabric until I get the folds and composition that I want.

Hermès #1

Take one or two fabric pieces and discuss your interpretation into your paintings.

I was attracted to the beautiful design, colour, and silky texture of one of my wife’s Hermès scarves. In arranging its folds, I tried to emulate the image of water flowing over rocks since that’s what the design reminded me of. The most difficult part of the painting was capturing the texture of the silk.

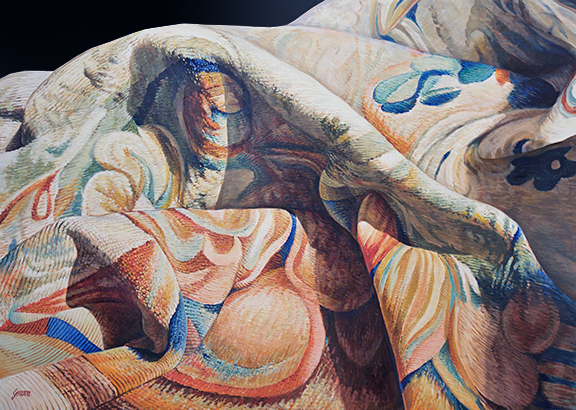

Hermès #3, 24 x30 inches, Oil on canvas

What different techniques come into play when you paint two very different fabrics, e.g. tapestry and silk?

There are certain fabrics that couldn’t be more different. With silk, you need to use a very light touch with your brush to capture its fine texture. I glaze many areas to help with the tonality of the colour.

My Tapestry, 27 x 36 inches, Oil on Canvas

In painting a tapestry, I use a different approach. Since the texture is much coarser, I mostly use hog bristle brushes. For the fine detail, I depend on red sable.

Comment on the importance of water in your work.

Water is wonderful to paint because it’s transparent and reflects every object that’s beneath it and around it. I love painting water because it reflects nature in its own distorted and beautiful way. Water is also quite mesmerizing; it captures our thoughts and brings us peace. I find painting water very therapeutic.

Tranquillity, 33 x 37 inches, Oil on Canvas

With your painting ‘Gondolas at Rest’ what are your thoughts on painting places people know and recognize?

Gondolas have always been a very popular subject matter for many painters. Like many other artists I, too, am drawn to their romance, beauty, shape, and colours, and I can’t help but paint them. In “Gondolas at rest” I recreated an image of a group of gondolas that stuck out in my mind. I remember seeing a lot of blues, which initially attracted me. When I looked closer, I noticed the contrast between a rough canvas cover and the oily-looking water around it. A piece of red fabric in one of the gondolas also jumped out at me, and I instantly knew I just had to paint this powerful image.

Gondolas at Rest, 27 x 38 inches, Oil on canvas

Discuss your botanical work.

What I love most about flowers is the delicate structure of the petals, their beautiful shapes, and the vast array of hues. I’m often amazed at how many colours it takes to capture the beauty of a white peony. The transparency of a flower’s petals is something to behold. So many colours reflect upon them, and they have such a delicate composition. The sensuality of a flower is what I try to capture.

Peony from Michelle's Garden, 28 x 36 inches, oil on canvas

Size: Most of my botanical work is large, a typical piece is 26 x 30 inches

Background: I use black in most of my botanicals to give it contrast

Use of composition: Composition is most important; I try to view a flower from an unusual angle.

Peonies, 30 x 35 inches, Oil on canvas

Use of enlargement: I photograph most subjects and work from my computer

Discuss how lighting influences your architectural works.

The Chapel at La Badia, 24 x 36 inches, Oil on canvas

In painting lighting is everything. When I travel to Europe to find architectural subjects, the early morning or late afternoon light is the light that gives the structures the dramatic light that I’m looking for. I never bother to look for subjects in the midday light because it is flat and boring.

Ca d’Oro, 30 x 42 inches, Oil on canvas

Contact details:

Joseph Genova

http://josephgenovafineart.com

joe@josephgenovafineart.com

Joseph Genova, New York, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May, 2018

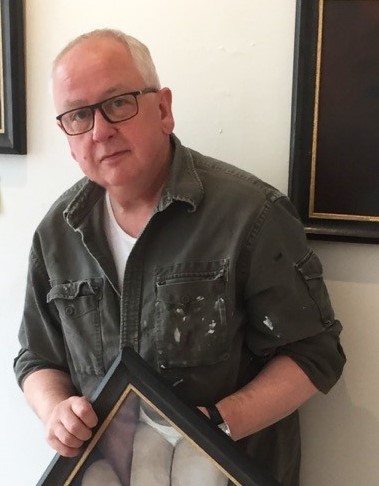

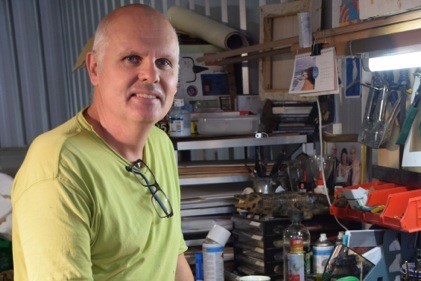

Kevin Gordon

Clear Sea Urchin

Expand on the influence your parents have had on your glass career?

With both parents being artists, I guess they laid the seed, I was always heading towards a creative career it took a while before moving into glass and fully appreciating it as a medium. I worked with my parents, part time for a year or 2 before I set up business working in architectural glass for 4 years before I moved to Victoria to set up a cold working shop alongside my sister glass blowing studio which is when I started to produce exhibition/gallery work. I was in Melbourne for 3 years before returning to Perth. In my family we have all help and influenced each other in our work and we are all quite individual in our style and use of glass. In the early years in Perth glass as an art form was almost non-existent, when I returned to Perth a glass blower David Hay also arrived in Perth, we became the nucleus to establishing the glass blowing studio there and my parent studio became the very important in the cold working side.

Shape can be found in both the form and surface of your work discuss.

In my work I enjoy natural lines in the forms that have balance.

In the design process of my work I look for how nature evolves, I look for the underlying logic and formulas that create natures designs, not so much to imitate but to look how it is formed. I use this by breaking down the design to the basic elements or fractals which repeat in a form of mathematical formula which build up to make the whole design.

Clear Sea Urchin, detail.

Your glass is housed around the world. Take a piece and discuss where they are now and what it has meant to you and your career.

To my mind the most important piece is the large colourless Sea urchin that is housed in the NGA, this piece was purchased from the sea form exhibition i had Form Gallery "Systema Naturae" this piece was the largest work I had completed and was the centre piece for the exhibition, it was also the first of the sea urchins that I had used only using the qualities of the glass without colour.

What made also special for me was when it was first exhibited in the NGA it was displayed very well, it was displayed in a big glass case in a small black room by itself with lighting only on the work, my niece on school excursion to the NGA after told me she was so excited to see it and to hear it was like the Jewel in the pink panther movie the way it was displayed.

Clear Sea Urchin

Has your series ‘Sea Form’ come from the Australian Coast?

The sea form exhibition arose from an exhibition I had at form gallery in Perth, it was a progression of work I did in the study of the use of fractals in my work which sea form designs are made of... the research was mainly from the time I got access to the natural museum in Perth where I got to explore and study their collection of marine life.

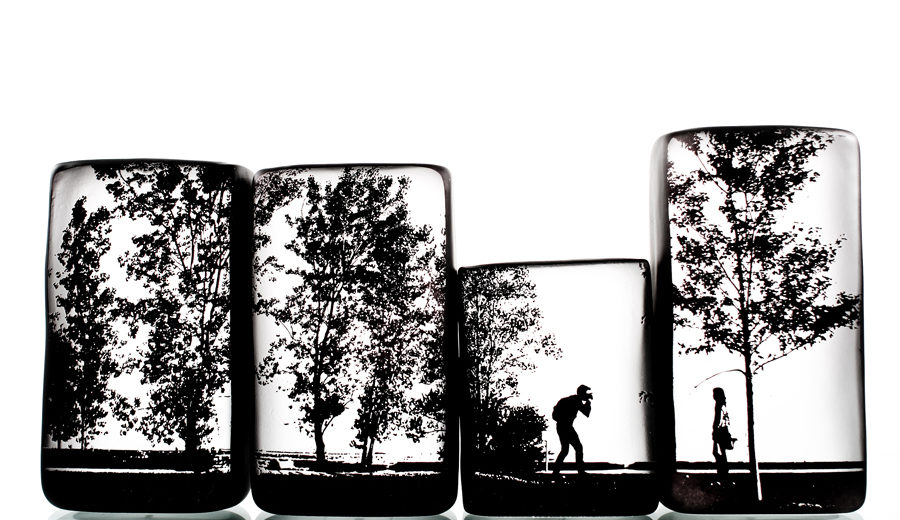

Discuss Rainy Daze

Rainy Daze this was one of the first works where I used lens as a feature in the piece which has become prevalent in many of my works, this work is held in The USA at Mobile museum of art.

Rainy Daze

Colour and glass go hand in hand – explain your use of colour.

Colour has always played an important element in my work, I did a year course on colour theory when I was studying painting in my early years which in much of my work I use this knowledge when I use multiple layers of colour then to cut back through the layers. the understanding of the colour wheel is important to make colours, for example if you put blue over orange it will become a gray because of them being opposite on the colour wheel they cancel each other out.

Expand on your work Deep Forest

Deep Forest, this work was a piece which I used three layers of colour on the internal and three on the external surface which I worked all surfaces so the outside colours shaded to the inside and the inside to the outside colours. after I had finished carving I pre-polished by hand and then we fire polished it which was at the time experimental process where we reheat the carved piece back above annealing temperature and the reattached to the pipe and then into the glory hole to melt the surface to a high polish.

Deep Forest, 420 x 280 mm

Graal – can you expand on this term?

Graal technique is a process I occasional use... it is a two stage process where we blow egg shape form with an overlay of colours which we call the embryo, at this point we take it off the pipe and anneal it… once cooled I carve design through the colours, then reheat the piece up slowly over night and once above annealing temperature we reattach to the blow pipe and gather more glass over it and then blow it into its form leaving the design suspended within the glass.

Explain the use of colour in Southern Lights.

Southern Lights this was a set of three works in what I would call my colour fractal vein of work, these works are about colour, also have work colour on inside and outside surfaces and then fire polish with the use of lens to give depth to the work… this set was exhibited in Sweden at the Steninge World Exhibition of Art Glass, Steninge Palace.

Southern Lights

Discuss the complexities of Humanity.

Humanity

Humanity, this work with engraved faces covering the surface, this is a small piece but quite solid with an internal bubble to reflect the faces when looking through the lens. the faces are engraved into triple overlay of colour and then hand polished.

Humanity

How do you like to have your work displayed?

Lighting is important with glass and each piece needs to be considered individually to how best to light… some enjoy natural light while others look best in a darken space with a spot light above or reflecting from wall behind. it is nice to see a work given space sitting on a plinth.

Contact details:

Kevin Gordon

mail@kevingordon.com.au

http://www.kevingordon.com.au/

Kevin Gordon, Red Hill, Victoria

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May, 2018

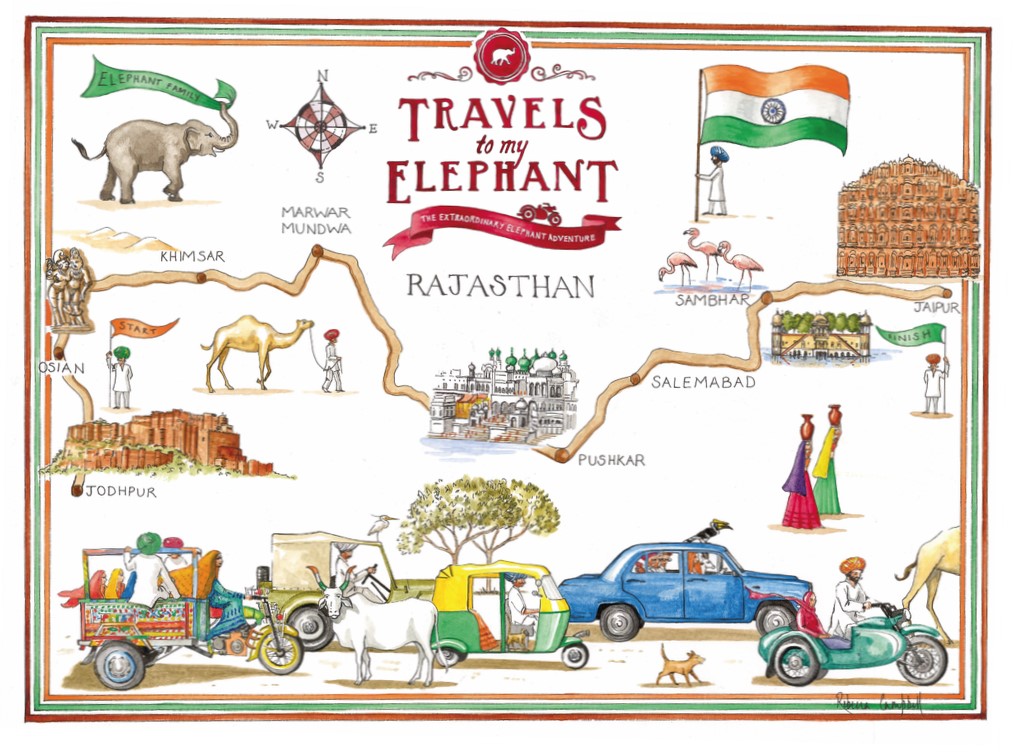

Anton Thomas

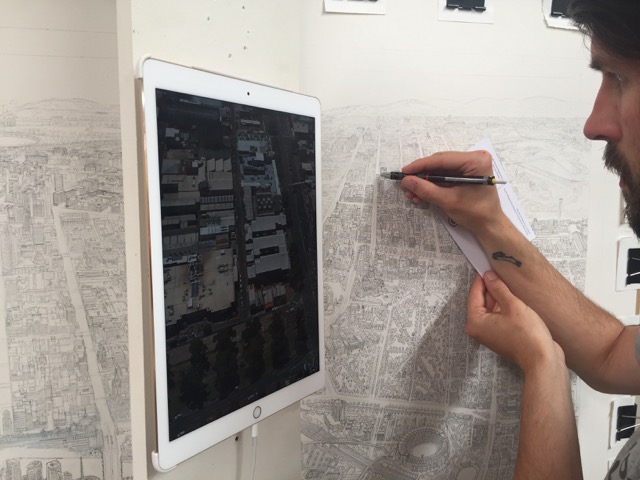

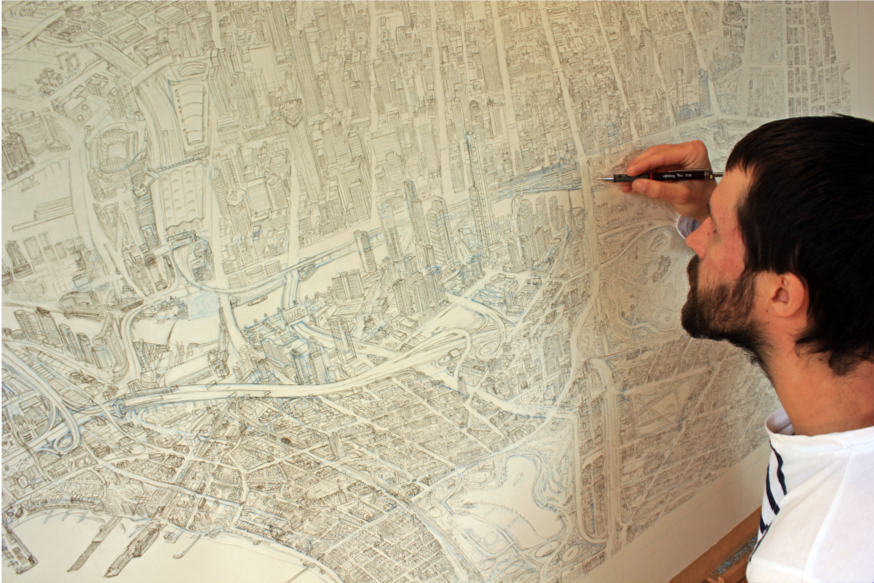

Can you discuss how important research and preparation is to your work?

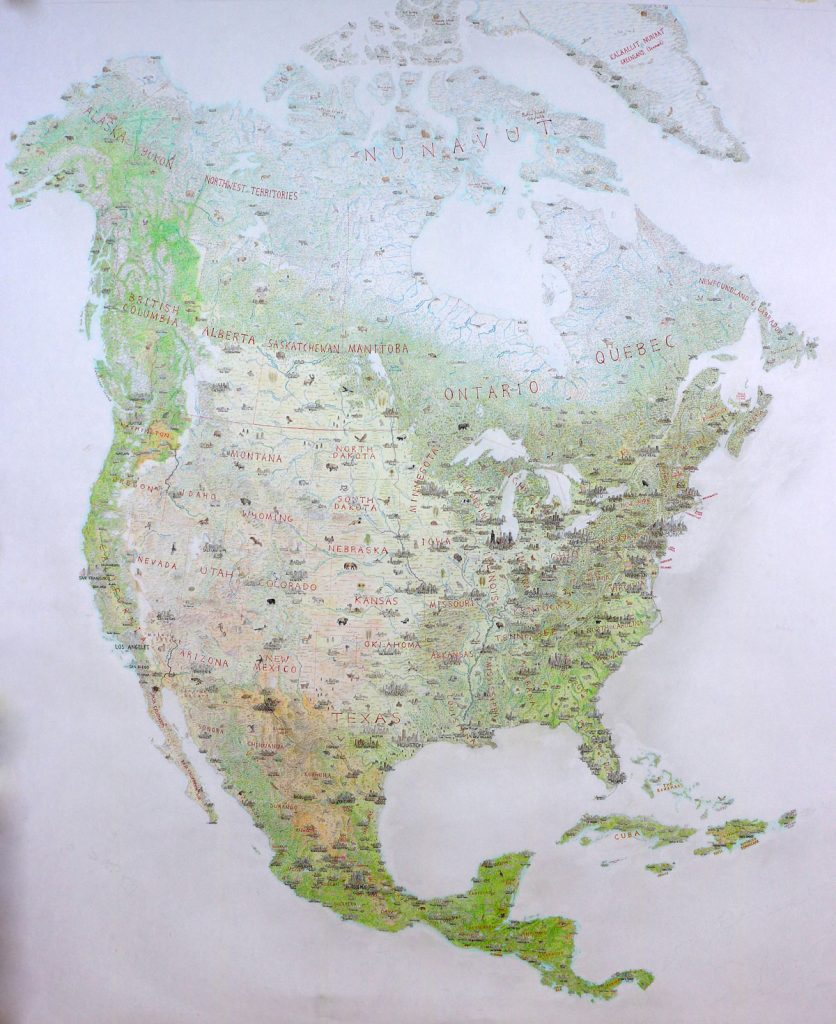

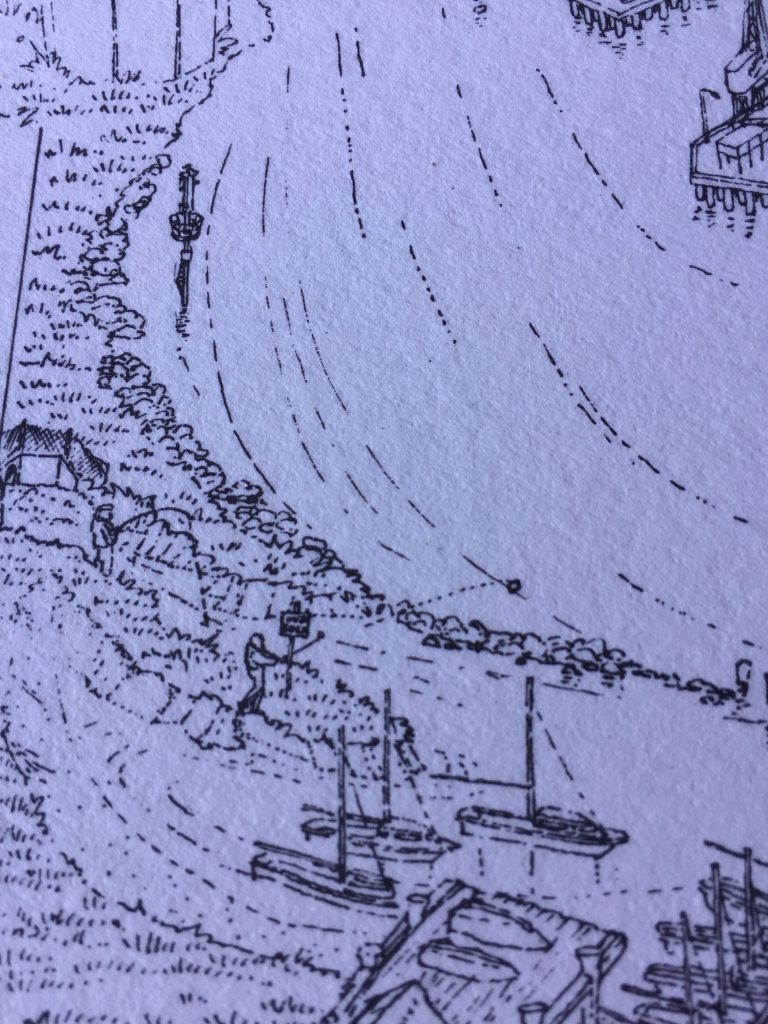

I estimate that some 35-40% of my overall labour time is research and prep, the rest being time spent drawing. This may seem a high amount for a completely hand-drawn artist, but my goal is to make maps that are as informative as they are artistic, so I spend a great deal of time with real-world data. I’m drawing real places, that real people live in, so it’s critical that I research properly to ensure I capture something of the feel of a place.

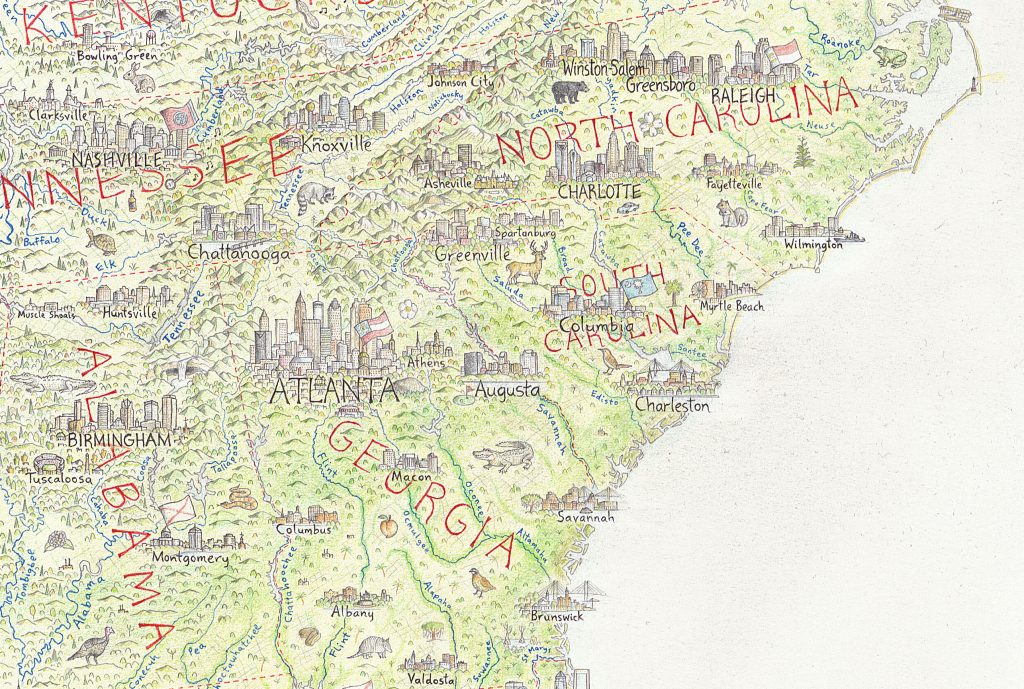

Southeast, USA

To make sure content is accurately geolocated within a region, I have to spend a lot of time prepping the area. This involves plotting out where everything must go, creating a pencil blueprint that I can then fill in.

You make the comment, ’By vividly illustrating geographic data, I hope to bring attention to dynamism and mystique of our world.’ Discuss.

Maps have always been a critical lens by which we view the world, and it never fails to amaze me how quickly anyone gets immersed in a map of an area they know well. Show someone a map of their country and they’ll quickly start telling stories about their lives and travels while tracing their finger along highways and coastlines.

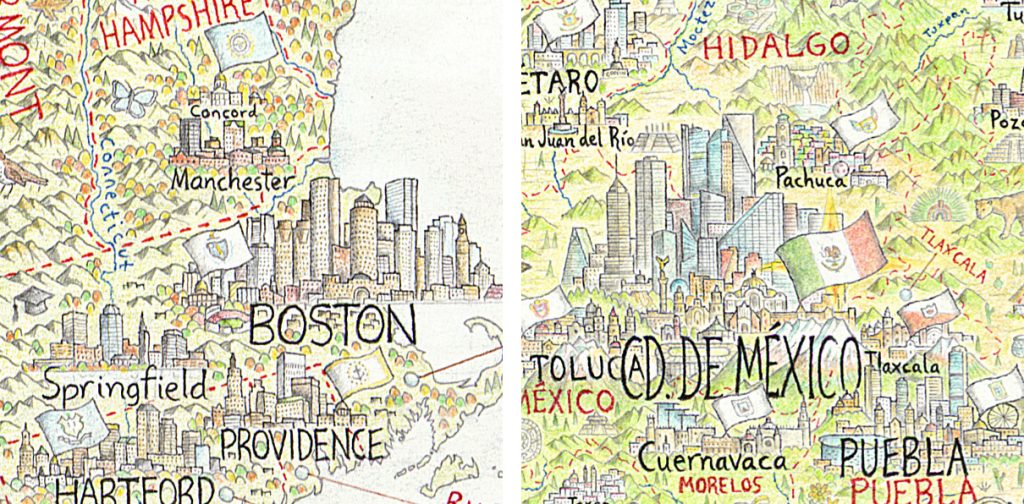

Capital Cities

There is a big demand for good maps, but in the age of the smartphone there is less and less practical need to peruse a map - we can just be navigated around with ease. I’m by no means a luddite about this, I’m a big fan of these tools. Nonetheless, this is causing a decline in societies (already shaky) geographic literacy, and I feel the space has been blown wide open for compelling traditional cartography to reconnect us with geography. Our Earth is more magical, awe-inspiring, treacherous and mysterious than any world conjured up by the great fantasy authors. I feel that by illustrating a map with true data, drawn in an elegant and fantastical way, it can capture anyone’s attention while educating them about geography.

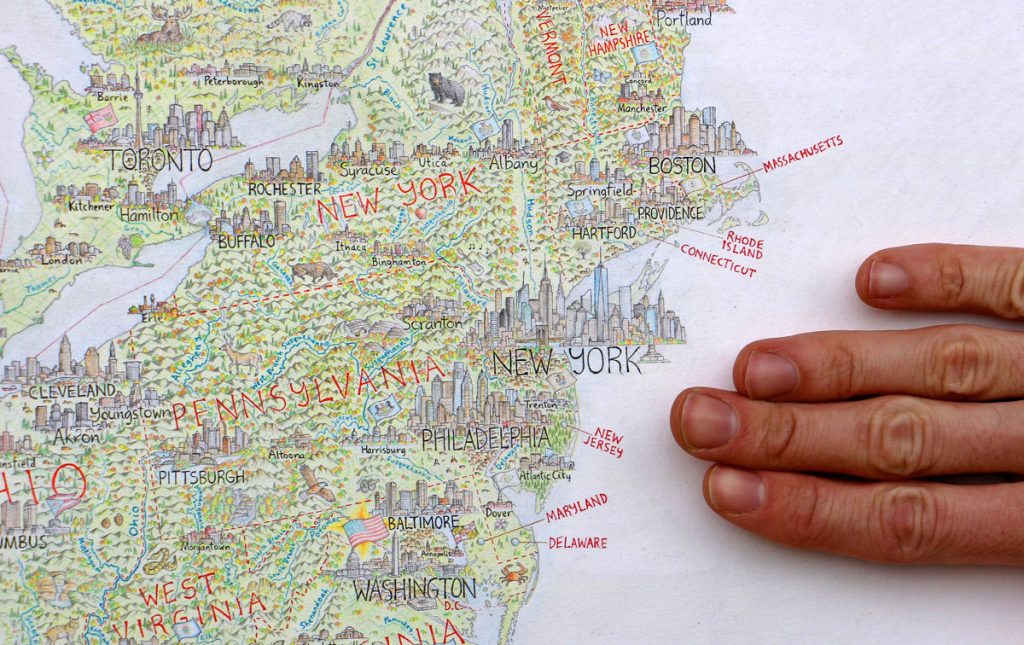

Hand scale, East Coast, USA

You are currently working on a huge map of The North American Continent, can you take two cities from your over 600 cities and towns, discuss their complexities as an illustrator?

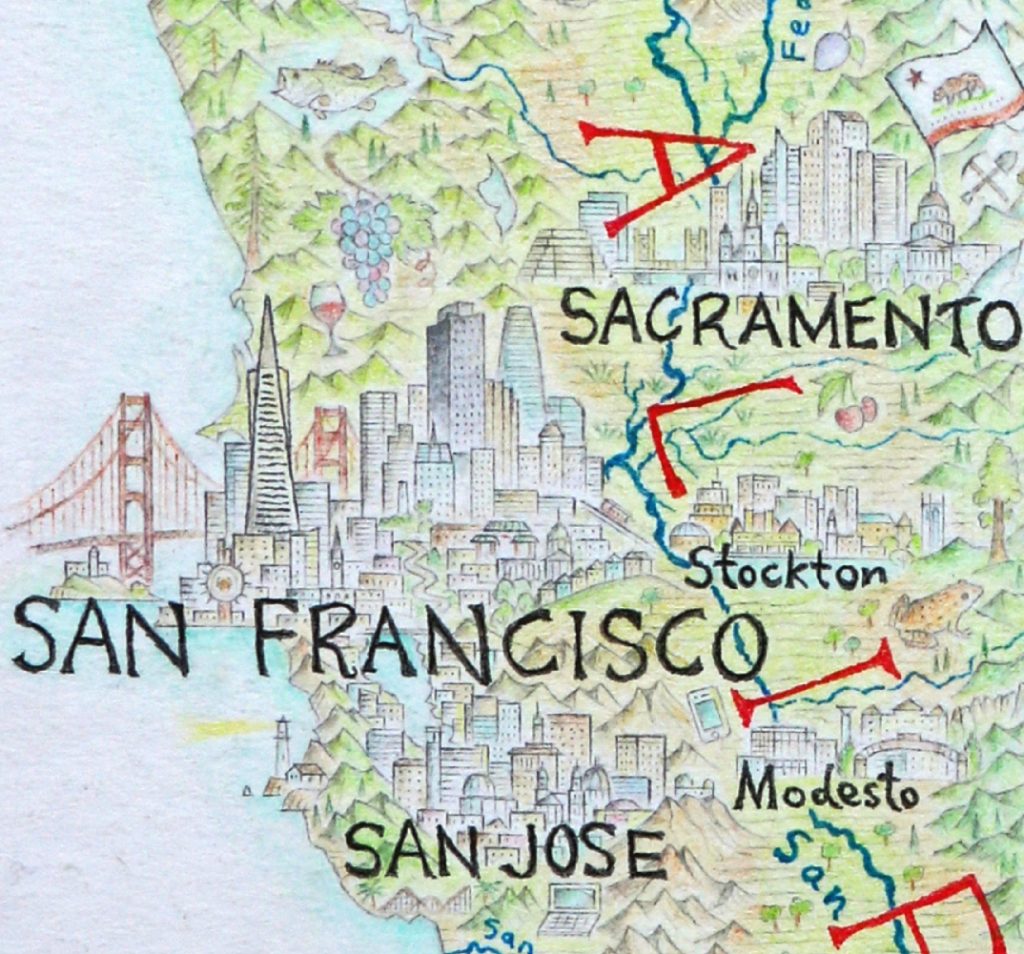

San Francisco. One of the most famous cities in the world, with dozens of iconic features to choose from, SF is a good example of how complex things can get.

The approach I take with most cities is to build them somewhat like the cross-section of a forest. I have the tallest buildings of the skyline – the canopy – towering in the background and creating the shape. Meanwhile the foreground is where I build an understory of content, and have a chance to include the smaller, more finessed landmarks of a city. In the case of SF, I managed to fit Fisherman’s Wharf, the Ferry Building, Nob Hill, winding Lombard Street, Chinatown gate, City Hall, a tram, and a row of painted lady houses. The background has the tallest most distinctive buildings creating the skyline, along with the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz. This one city alone took many hours of research, prep, and drawing.

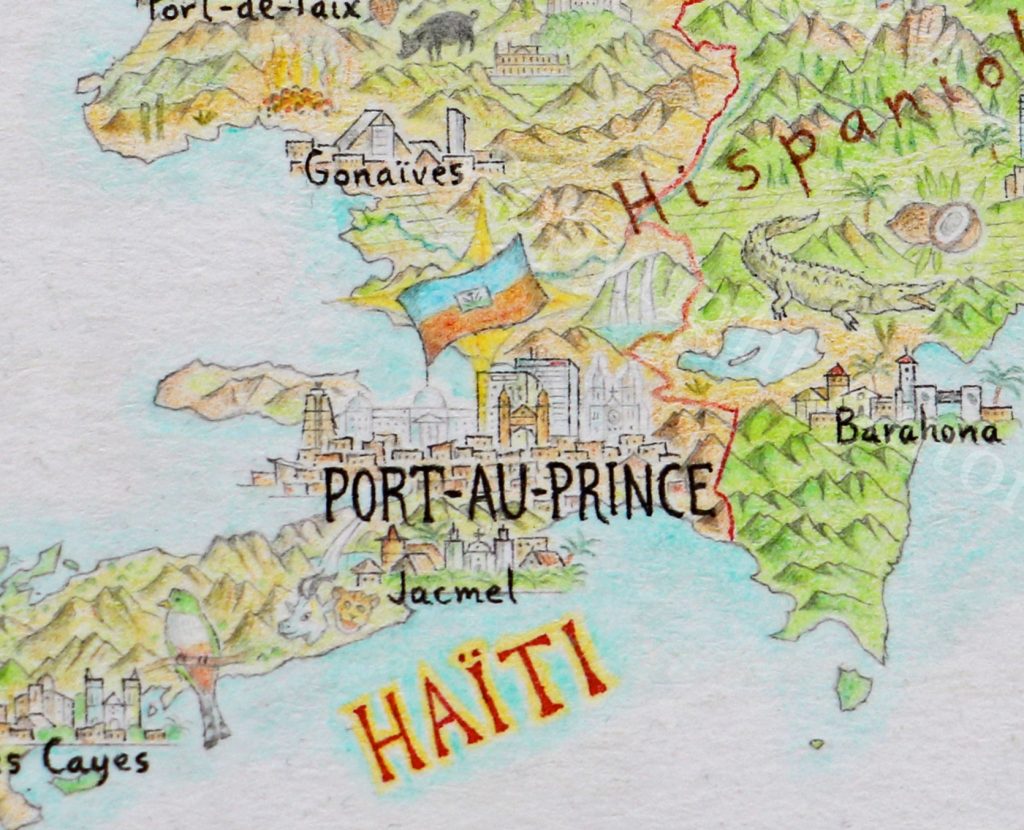

Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Some cities have such unique specifications that I have to really think outside the square. Port-au-Prince was devastated by the Haiti earthquake in 2010, which destroyed many buildings, including most of its iconic civic landmarks.

Port-au-Prince, Haiti

So, the kind of features I normally look for are simply not there anymore. This includes the National Palace, which as the seat of government is the building I usually draw a nations flag upon. After a lot of research to determine what iconic buildings still remain and what was lost, I was unsure the best way to handle a portrait of the city with the finesse and care required to do it justice. Finally, I chose to draw two of the iconic buildings that were destroyed – the National Palace and the Cathedral – in a light, ghostly style to create a contrast with the other buildings that still stand. I wanted to reference the earthquake, which left an undeniable mark on Haiti’s contemporary geography, while also showing that the spirit of the city lives on.

When and how do you decide to add a town to your map?

When do you decide not to include a town or city?

This has proven to be one of the most controversial elements of my map, and there’s no easy way around it. It’s controversial because if someone’s beloved home city is missing, it may well frustrate and annoy that person… which is understandable. I have a population criteria to determine city inclusion, which goes something like this. If a city has more than 100,000 people in its metropolitan area, it gets included. At the large scale of my North America map, I usually choose the hub city of a metropolitan region rather than try to include everything – I simply don’t have the space. For example, Seattle is just Seattle, I did not attempt to squeeze in Tacoma, which is its own city but is still considered part of the larger Seattle metropolitan area.

In the northern 90% of Canada, as well as Alaska and Greenland, I dropped the city inclusion right down to 1,000 people to correct for a much lower population. Otherwise, there’d be no towns to draw up there at all.

Finally, all capital cities are included, with the flag of their entity flying above the legislature buildings. This goes for both international capitals, and state/provincial capitals of the US, Canada and Mexico.

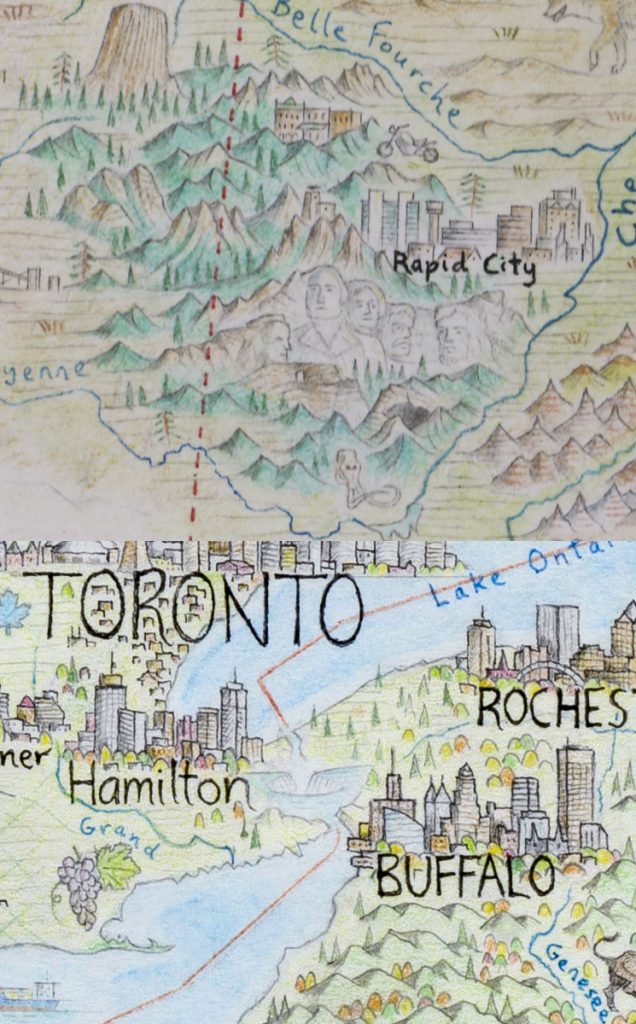

What have been some obvious landmarks that people will be looking for?

For anyone who is from North America, they’ll naturally go straight for their home city or region, and it’s always fascinating to get feedback from a local. I’ve had people tell me that I drew the building they work in, or the church they were married in, and that’s always so exciting. Overall however, the most commonly searched-for features would include the cities of New York, LA, San Francisco and Chicago, along with Niagara Falls, Mt Rushmore, the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and more recently, Trump’s wall along the Mexican border… which no, I will not be drawing.

Rushmore, Niagara

When you add animals how do you decide when and where to place them?

Every animal is a little different. The vast majority are wildlife, rather than livestock, so I take great care to ensure that I’m putting animals within their actual range. If I want to draw a tarantula somewhere in Arizona to give it more of that desert southwest feel, then I’ll look at the different species of tarantula found in the area and make sure I get the right one in the right place.

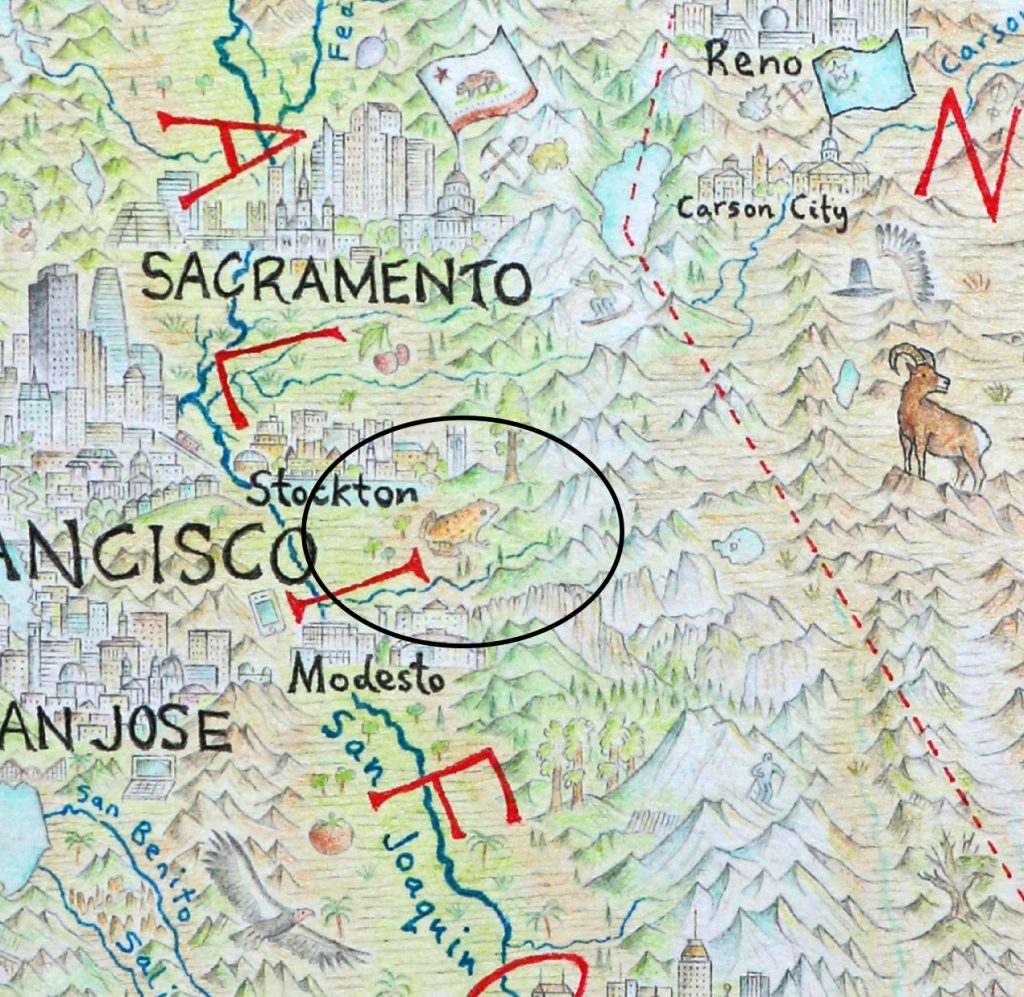

Some animals are chosen based on their symbolic significance, as animals often have important roles in regional iconography. I especially love anything that has multiple layers of meaning behind its inclusion. For example, the Californian red-legged frog in northern Cali is 1) the official state amphibian of California, 2) endemic to that region, 3) drawn in Calaveras County, which is most famous for Mark Twain’s book The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, which 4) lead the county seat of Angel’s Camp to being nicknamed “Frogtown”. So right there are four reasons why this frog made it onto the map.

Californian red-legged frog

Why did you decide to add Cuba, Jamaica, and The Bahamas?

The map is called The North American Continent, so it’s all about the entire region. North America as a geographic region includes Central America all the way to the Panama/Colombia border, it includes Greenland, and it includes the Caribbean – hence the focus on Cuba, Jamaica and The Bahamas. Also as the bulk of my print sales will be in the US and Canada - certainly the lions share of the continent - I want Americans and Canadians to learn about and consider their wider neighbourhood.

North American Continent

North American Continent

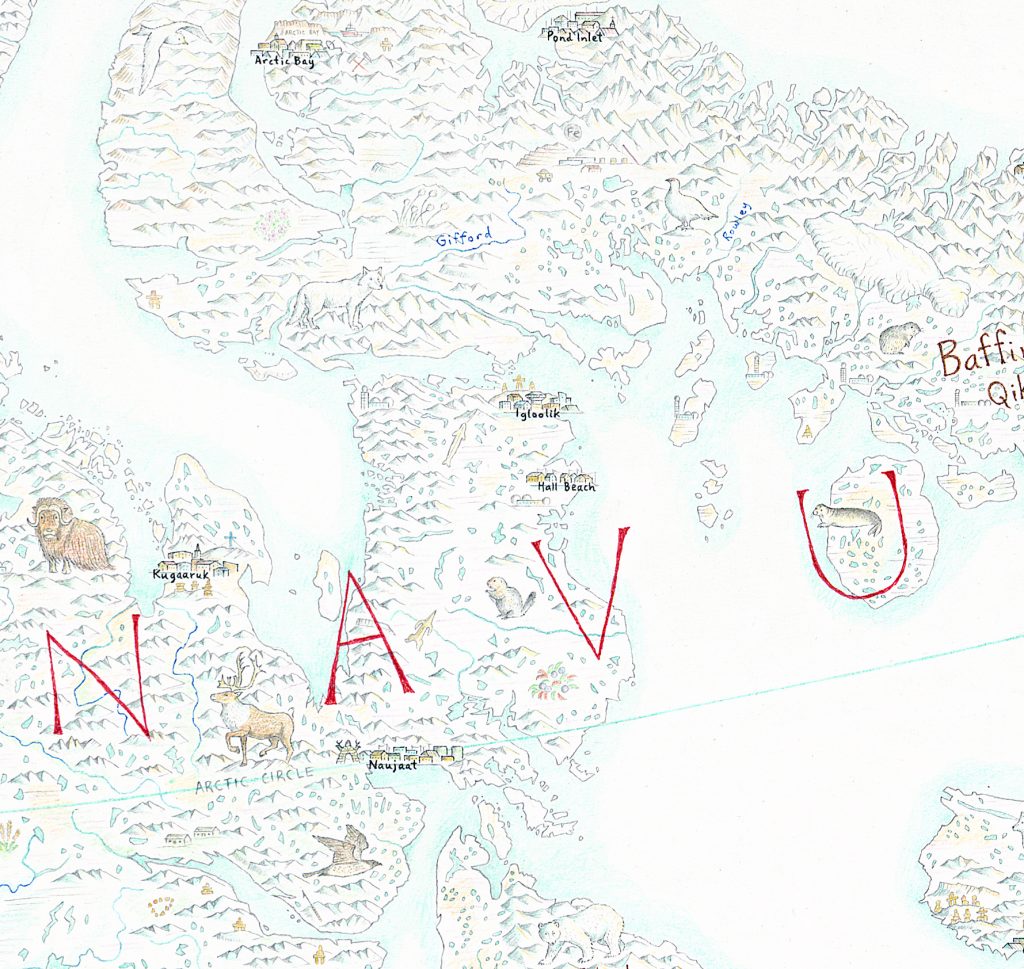

Discuss the differences involve in depicting Arctic landscapes onto you map?

The Arctic has been a fascinating region to focus on, and required a different approach to the rest of the map. For one thing, being a frozen tundra landscape, the base colour is the paper: white. I had to be very creative with my colour pencils, using a lot of blues and purples for shadows, and yellow or ochre for highlights. It was a region I could move comparatively quickly through, because of the lack of cities, which was nice after punishing slogs through Central Mexico or the American Northeast. There were big challenges though. Simply finding content at all was not always easy, and I had to learn to let the map breathe.

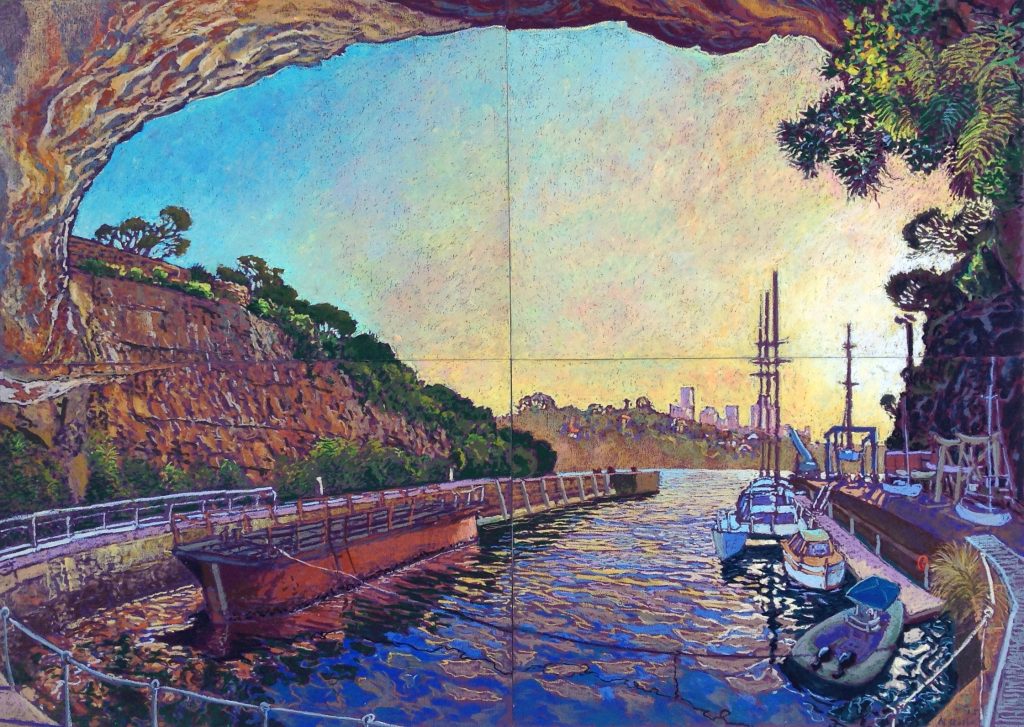

Arctic

To be okay with wide open spaces that had infrequent features. And while the Arctic has many wonderful animals, I did cycle through the basics quite quickly (polar bears, arctic hares, seals, walrus, artic wolf, arctic fox, lemmings, muskox, caribou etc). Also challenging were the coastlines of the Canadian Arctic and Greenland, which are some of the most complex in the world. Trying to get the fjords of Greenland and Labrador accurate felt like I was playing 3D underwater chess.

I loved learning about the Arctic at the level I did, where I was reading all about these Inuit hamlets that few people have ever heard of, learning about the culture and lifestyle of peoples of the far North. Pangnirtung, Kugluktuk, Grise Fiord, places that boggle the mind to think about. Places that have days or nights that can last months, places that you’ll kayak on one day, and weeks later could be dogsledding the exact same spot. Places that seemed like another planet to the world I know, yet others call home.

Expand on the importance or use of red on your maps?

I use red fine-liner pen for any political divisions on the map. I label entities with it, and draw all my borders. International borders use an unbroken red line, while subnational borders (US and Mexican states, Canadian provinces) are delineated with a dashed red line.

Discuss Cruz de la Parra and why you have chosen to add this historical cross?

The Cruz de la Parra is located in southeast Cuba, and is a cross that was apparently erected by Christopher Columbus himself.

Cruz de la Parra,

This is an extraordinarily rare and historically significant relic. While the arrival of Columbus spelled doom for so many millions of indigenous inhabitants of the Americas, there’s no question that it was one of the most significant moments in world history, and the legacy of his landing is felt in every corner of the continent I’m drawing. I also featured his ship – the Santa María – landing at the Bahamas. I was surprised to come across a relic that was so directly tied to Columbus, and it’s a major tourist attraction in this region of Cuba.

When did you first become fascinated in cartography?

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment, but somewhere around age 6 or 7 I suddenly found myself obsessed with maps. I would stay up late and draw the coastlines of New Zealand (my home country), the world, and my own fantasy lands. I believe it was something to do with the remarkable geography of NZ, and some of the beautiful flights I took between Nelson and Wellington. Also I’d been drawing animals and landscapes even younger than that, but they didn’t really merge into pictorial maps until many years later.

What lead you to have a career in cartography?

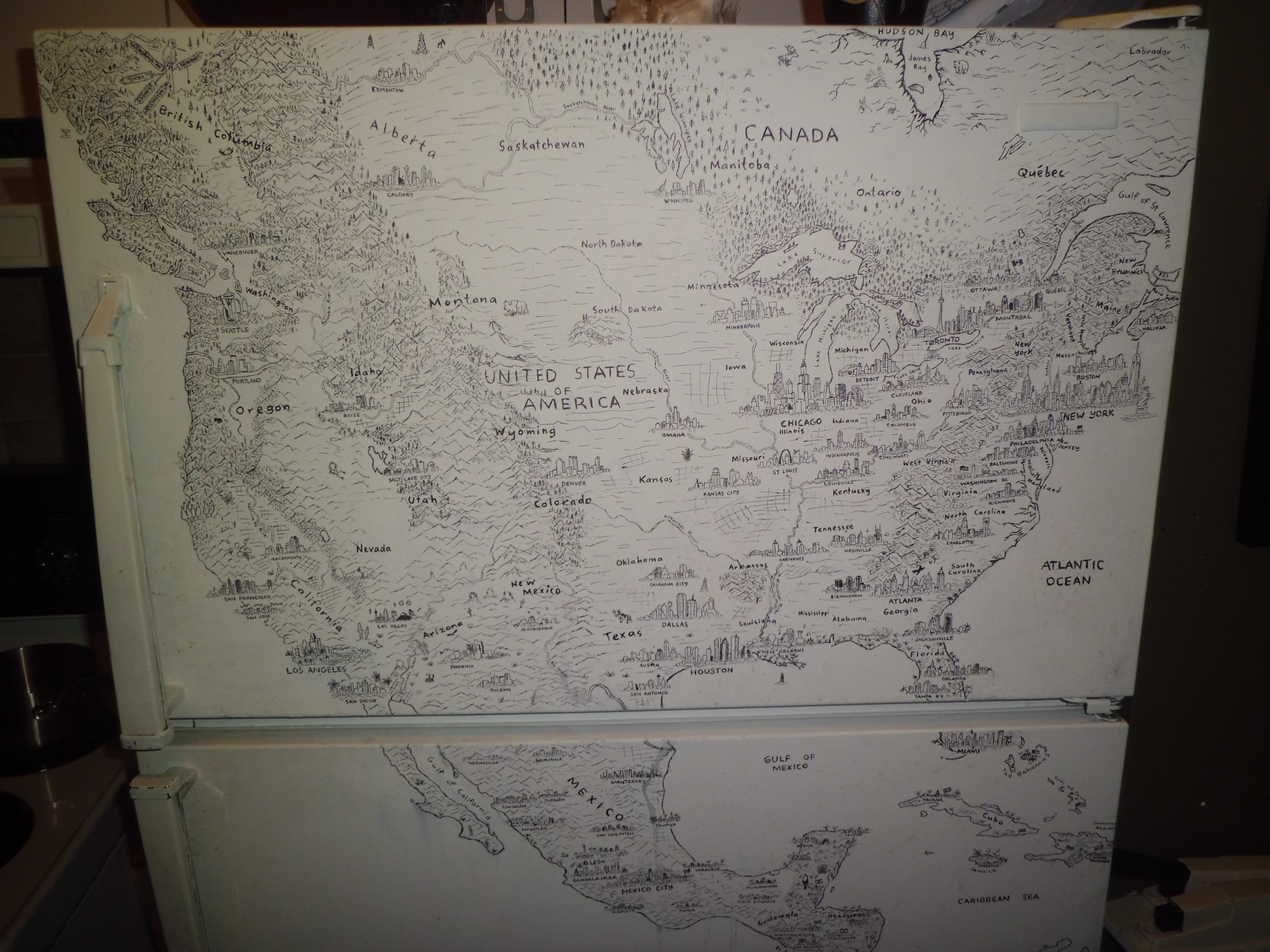

You live in Australia but are working on a North American map. How did this come about?

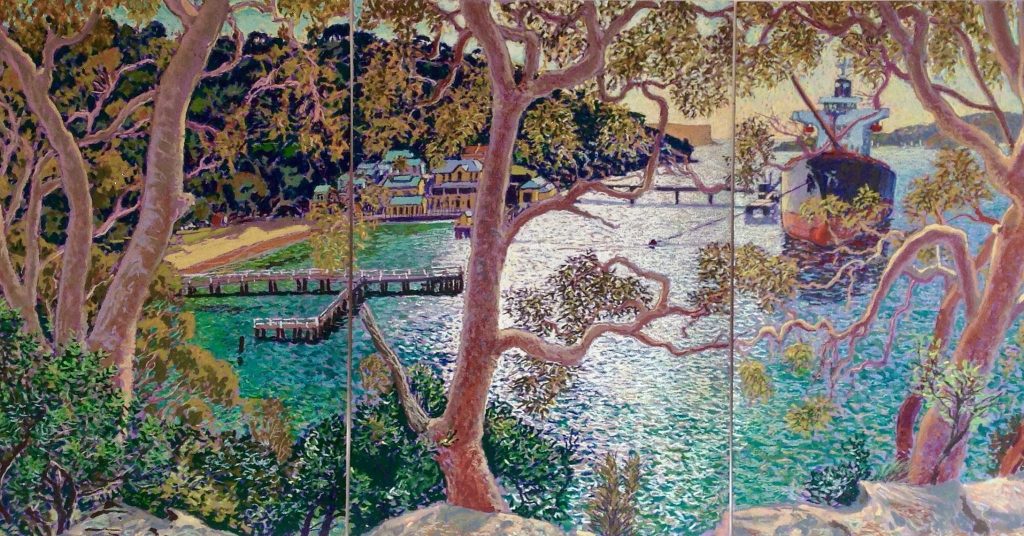

At age 21 I moved from NZ to the USA with a one-way ticket, and ended up spending almost 2 years moving around North America, taking all kinds of jobs – from cooking to laying grass sod, as well as playing a lot of live music. It was the first place I ever went overseas, and I was blown away by the geography of the continent. I could not believe the variety and sheer scale of it, and it reignited my deep passion for cartography. Toward the end of my travels there, late 2012, I was living in Montreal and my housemate asked me to draw him something as a keepsake before I left. He’d noticed I was half-decent at drawing, and encouraged me to do so… on his refrigerator. We had this crappy old fridge that had rust stains on it, and after he painted it over with white house paint he suggested that that could be my canvas. So, I proceeded to draw a map of North America freehand on the fridge with pen, in which I drew little skylines for each of the major cities. I absolutely loved the process, finding it to be creative, stimulating, and fun. Meanwhile, everybody who saw the fridge loved it too, so I thought hey – I ought to follow this up.

Montreal Fridge

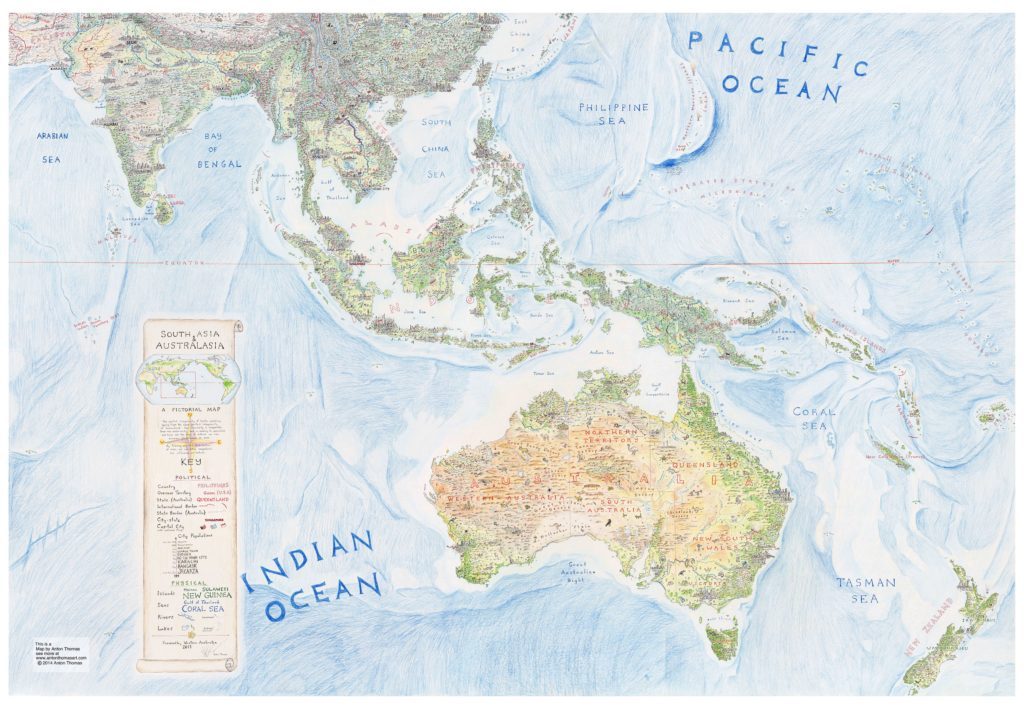

Six months later I’d moved to Perth and I got to work drawing a map of South Asia and Australasia (on paper this time), teaching myself to use colour pencils.

South Asia and Australasia

This gave me the skills and confidence I needed to draw North America properly, which I commenced upon moving to Melbourne in early 2014. It has been almost four years since I began The North American Continent, it is my love letter to a remarkable part of the world… a place that taught me to think bigger, and to try something different. In 2016 I got a huge amount of exposure from a feature on National Geographic’s Best Maps of 2016, which expanded my reach and showed me that there was a big market for what I’m doing. I spent much of last year developing upon this, while trying to finish the map, and embarked on a lecture tour throughout the US and Canada. Here is one of my talks from a cartography conference in Montreal. Moving into 2018, I’ve quit my dayjob and am now mapping fulltime. I expect to finish The North American Continent in a few months, and hope to have the first round of prints to market before Christmas.

Contact details:

Anton Thomas

Anton Thomas, Victoria, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May 2018

Rogan Brown

Expand on your comment, “Walking a narrow and sometimes contentious line between fact and fiction, observation and imagination”

When I say that my work is inspired by science it raises certain expectations particularly in relation to the question of accuracy; in simple terms how factually accurate are the sculptures I make? In reality, that question is far from simple because what I depict in my work are subjects that are mostly invisible to the naked eye and that can only be glimpsed through electron microscope images or alternatively through technical diagrammatic representations. Both these forms of representation are accurate to a point but are also misleading: a cross sectional diagram of a cell for example simplifies and schematises what it represents, and electron microscope images often use coloured filters which distort the reality of what is being depicted. I make use of the aesthetics of both diagrams and micrographs in, my work but they are only a starting point; as each piece progresses it is transformed through the creative process and embellished by the imagination because what I'm seeking to convey is a poetic essence and truth rather than a factual one. The difference between a fine artist and a professional scientific illustrator. It is the difference between understanding a landscape by looking at a map and understanding it by looking at a painting by say Monet; both are schematised representations, but one seeks to convey factual truth, the other a poetic, emotive truth. In my work I try to find a bridge between these two approaches.

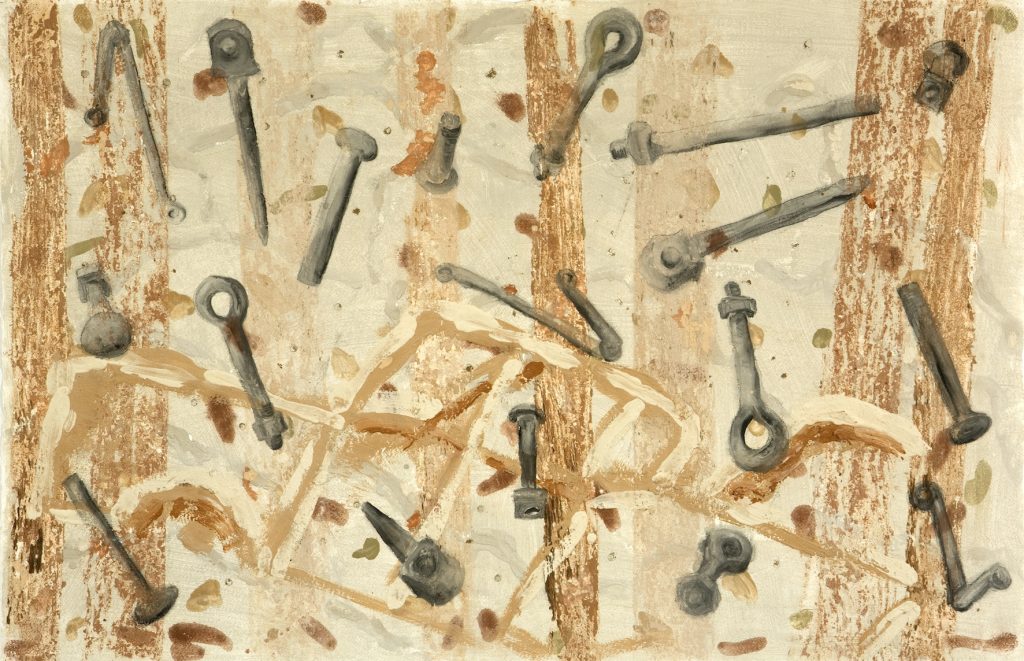

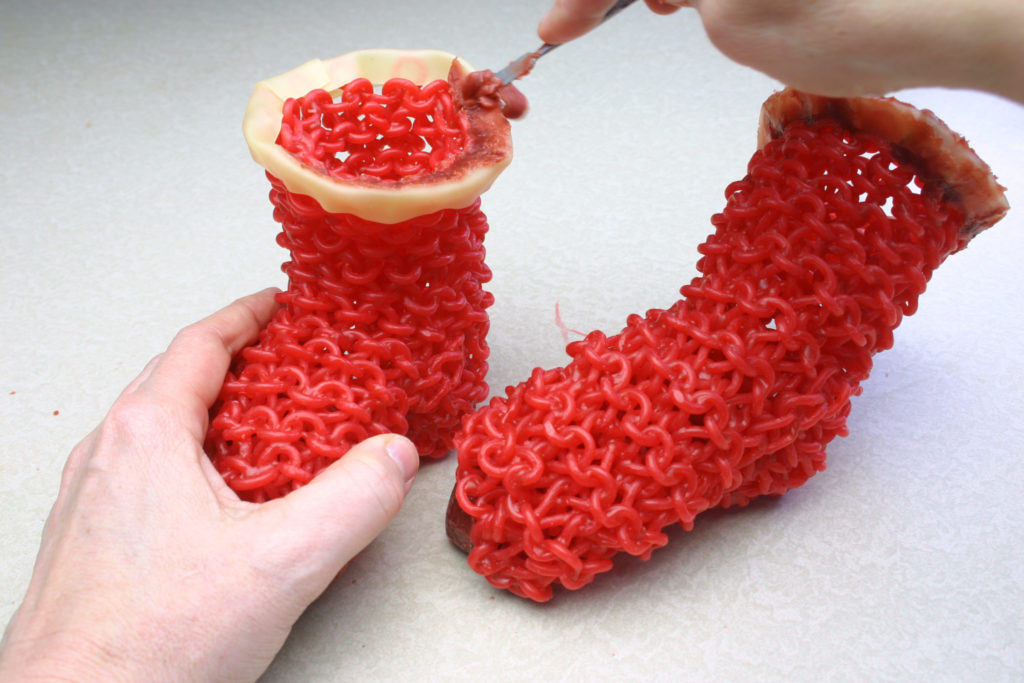

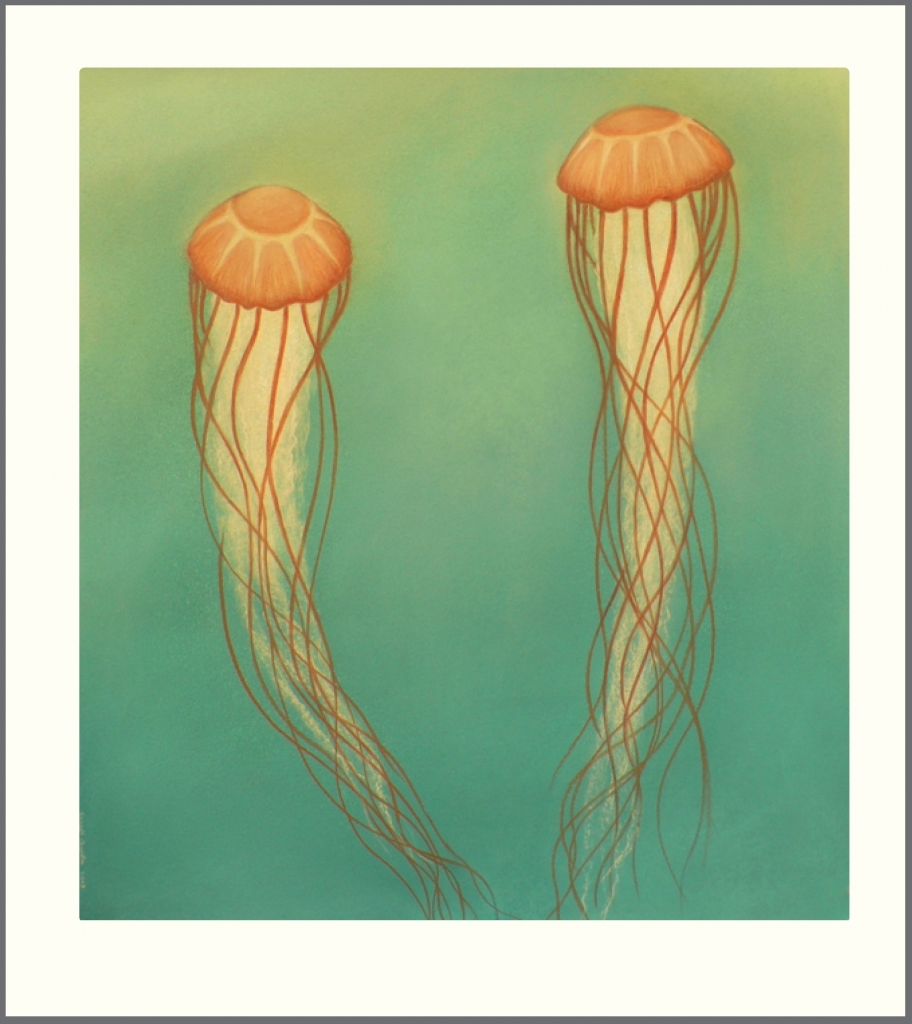

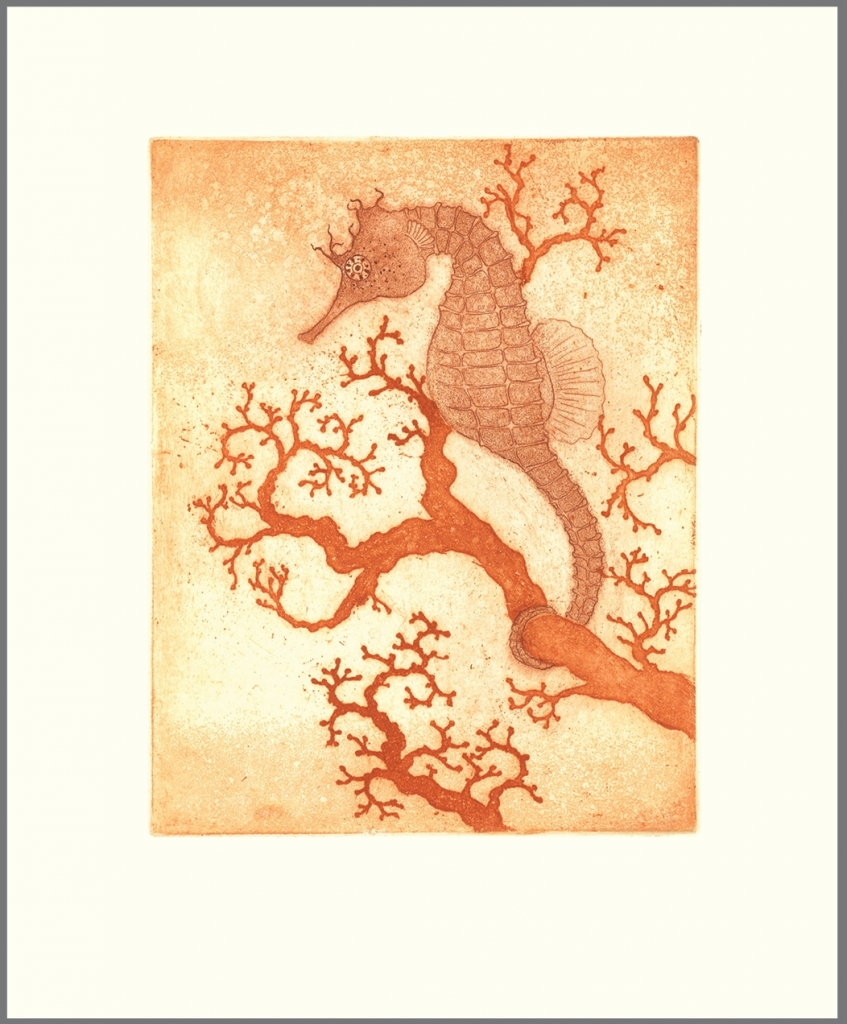

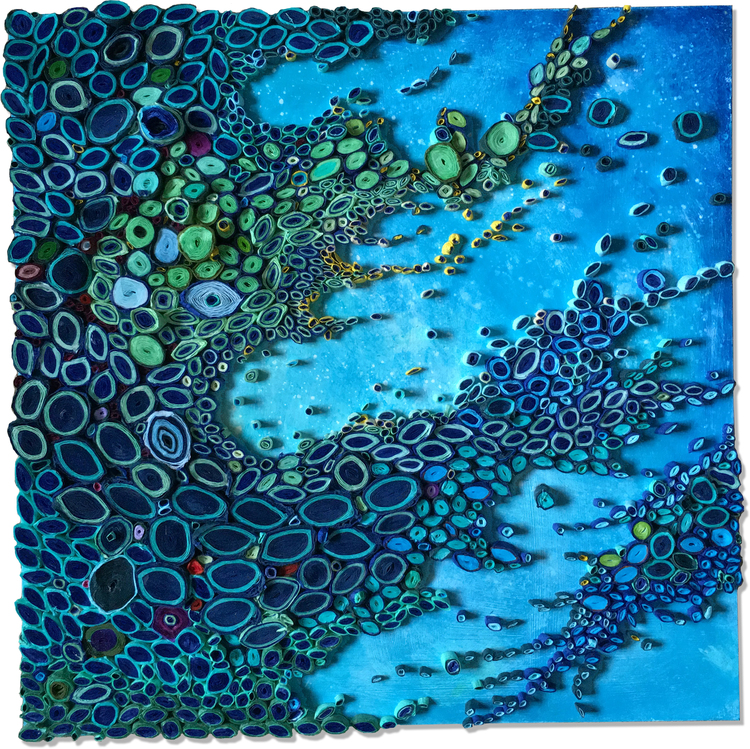

Reef Cell, 83 x 83 cm, Laser cut paper

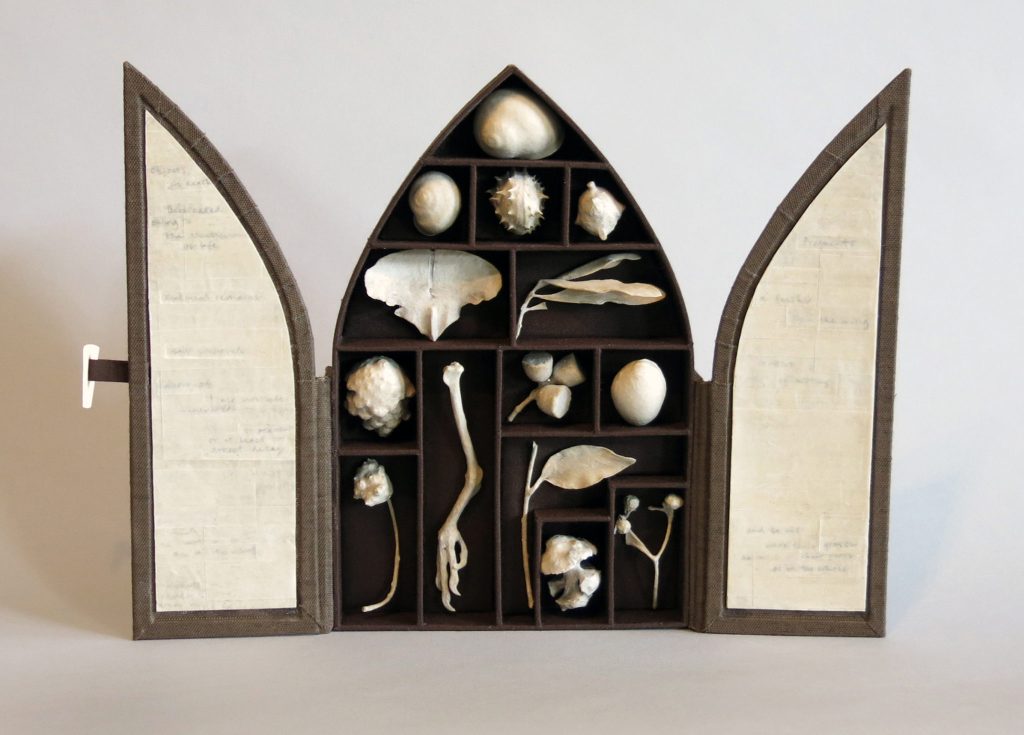

The humble chestnut husks have been very influential in your work, discuss.

Kernel, detail

I lived in a chestnut forest for 10 years and became fascinated by the strange surreal beauty of the tree's fruit: the sharp spikes of the husk, painful to touch, protecting the shiny mahogany fruit inside; such a stunning contrast of form and texture. This dynamic interplay between interior and exterior is seen throughout nature where skins or shells contrast with what they cover and protect. We see it in anatomical drawings of the human body, (another great source of inspiration) where the smooth skin is pulled aside to reveal the formal complexity of the organs and branching arterial systems that it covers. Likewise, the structure of the spiky orb of the chestnut can be seen repeated in other contexts, for example, on the microbiological level, in the shape and form of certain viruses. It's these structural echoes, parallels and patterns that fascinate me in nature and I constantly research them, trawling through satellite images of the earth and telescope images of the planets, microscopic images of bacteria and pathogens, electron micrograph images of cell structures, anatomical drawings, as well as pictures of birds, insects, reptiles, fish, crustacea, mammals...constantly searching for shapes, patterns and structures that are repeated at different scales and in different contexts: symmetry, fractals, branches, bubbles, waves, spirals.... These are the aesthetic building blocks of life, the architecture of the natural world and I use them to create hybrid sculptures, chimeras that make multiple visual references simultaneously.

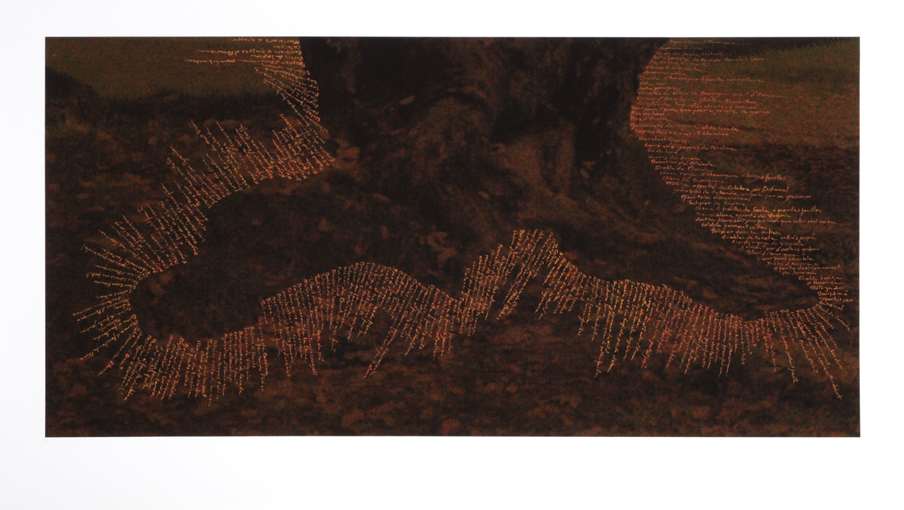

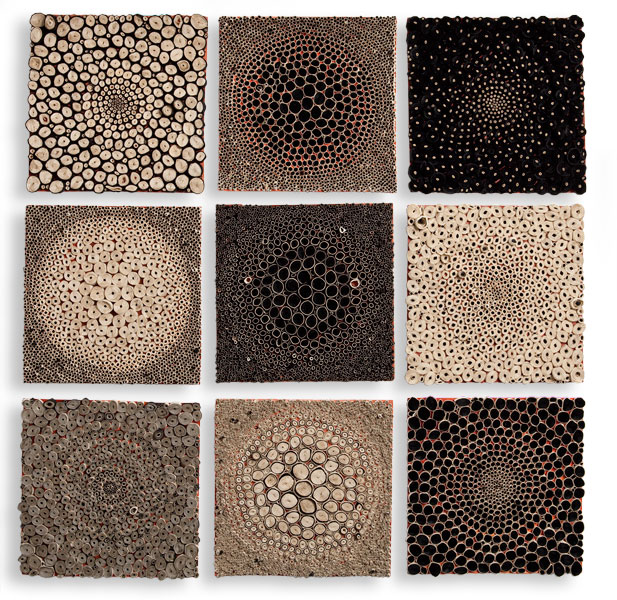

Kernel, 137 x 107 cm, Hand cut paper

Can you briefly explain the process and technique of your work?

Every piece starts with drawing, the finished work is really a layered three dimensional drawing. I start with small sketches then work these up into detailed full scale drawings that are then cut either by hand with a scalpel (eg “Cut Microbe” and “Outbreak”) or alternatively with a laser (eg Magic Circle Variation). Each cut is then mounted on hidden card and foam board spacers of 1 or 2 cms depth and finally each layer is mounted on top of the other, glued and pinned in place. The process is therefore long and labour intensive especially for the larger hand cut works that can take several months to produce.

You call your work sculpture rather than 2D work discuss this in relations to your work.

The pieces are in fact base relief sculptures that can be anywhere between 7 and 20cms deep. Although paper is the principal medium the essential element is light and by making them monochrome I maximise the interplay of light and shadow. The photos you see freeze the works at a specific moment with a particular lighting set up but in reality they change and move according to the changes in ambient lighting.

For me sculpture creates a more powerful, direct visual experience than 2D work because it is not the representation of an object, it is the object itself and asserts its own autonomy.

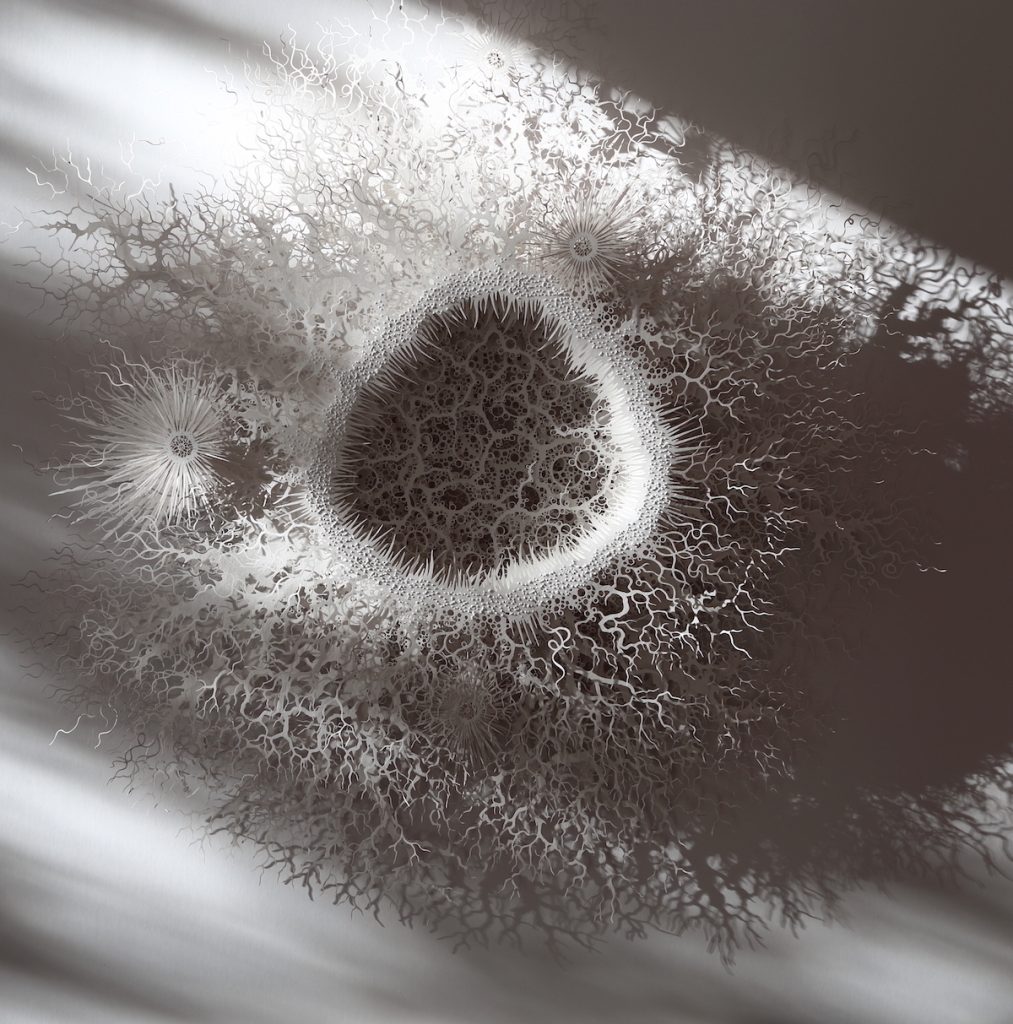

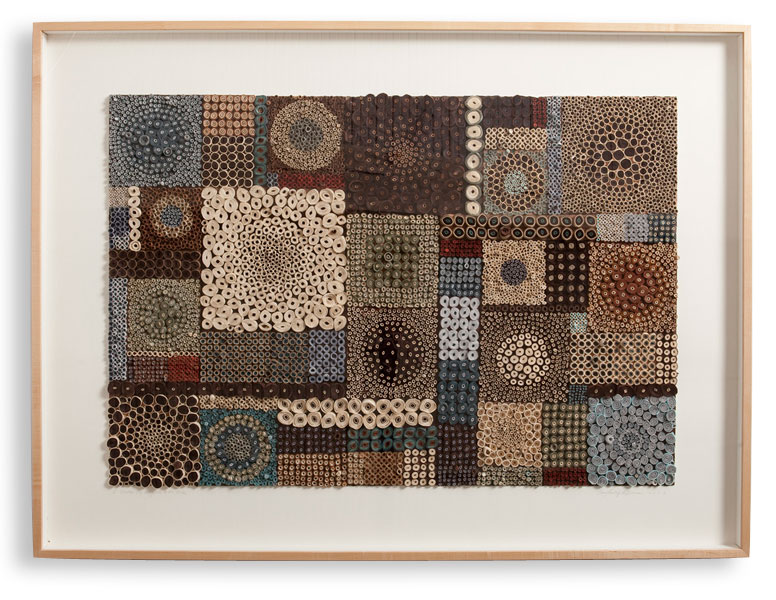

Outbreak, 147 x 79 x 20 cm, Hand cut paper

You have worked with scientists explain how this came about and one or two connections that have strongly influenced your art career?

I was invited to collaborate with a group of microbiologists who were in the process of working on a Wellcome Trust funded permanent exhibition focusing on the Human Microbiome, that is the vast colony of bacteria that live in and on our bodies and that scientists are only beginning to understand thanks in part to inexpensive DNA analysis. I was one of a group of artists asked to make work inspired by bacteria. I think the experience made me realise how large the culture gap is between the two disciplines; there is a sense that science is dealing with the hard edge of reality, with results changing and improving our lives in very practical, measurable ways, whereas art is really a little bit of entertainment, embellishing our lives but not fundamentally altering it. At a certain level this is not easy to argue against, art does not make planes fly or cure infectious diseases and its contribution to our lives is impossible to measure, but for me it is an equally valid reflection on the nature of the world we live in, teaching us to see the world in new ways or to see familiar things in a fresh light so that we become aware of the act of looking and seeing. As such the arts are just as crucial as science in helping us explore the meaning and purpose of our lives and in helping us maximise the experience of being alive.

In relations to science expand on how you use ‘Escherichia’ coli and enlarge this single bacterium into a large paper sculpture?

The exhibition that this sculpture is part of is called “Invisible You” (www.edenproject.com/visit/whats-here/invisible-you-the-human-microbiome-exhibition) and all the artists who contributed to it try in different ways to help us conceptualise and see in a new way something that is crucial to our existence and our health but which we most often regard in a very negative way, namely bacteria. Humans are symbiant beings, that is to say we live thanks to a mutually beneficial relationship with an unimaginably vast colony of bacteria that helps us in myriad ways, such as breaking down food in our gut and extracting all the good nutrients from it. Taken as a whole bacteria is not only good for us, it is essential to our survival but occasionally it can harm and even kill us, and it is these latter aspects that sadly tend to dominate public consciousness.

The object of the exhibition was therefore to educate the public about the benefits of bacteria and to try to change public perception. My personal aim was to try to make the words “beautiful” and “bacteria” associate in the mind of the viewer, so I set out to create a sculpture of a single bacterium that looked as beautiful as possible. I chose ecoli because it is more aesthetically interesting than other bacterial forms as it is covered long hair-like appendages called flagella that allow it to swim through our bodies and I knew I could use these to create a sense of movement and rhythm that would maximise its visual impact. Ecoli is also well known to the public as a bacteria that causes illness and I wanted to use that negative connotation to create a contrast with the beauty and elegance of the representation that I hoped to create.

Cut Microbe 2, 112 x 90 x 20 cm

Discuss the size of your work and the restrictions you have with size due to paper?

Paper's obvious fragility means that the sculptures need to be placed under glass or perspex in order to protect them. All the pieces are framed in bespoke deep rebate box frames under glass which are heavy and consequently difficult to transport so this limits the scale at which I can work. The largest pieces I've created are 150x150cms. Scale is a crucial aspect of my work. I'm drawn to subjects that defy our limited human capacity to imagine scale, for example bacteria which individually are unimaginably small but which, in terms of number, are unimaginably vast.The same is true of the neurons in the human brain, a subject I'm exploring at the moment. I try to reflect this contrast of scales by taking a very small subject such as a bacterium or cell, expanding it in size and then rendering it in minute detail.

Light must be a huge problem – how do you get this just right in your studio?

I live and work in the south of France which is very light all year round and my studio is flooded with light.

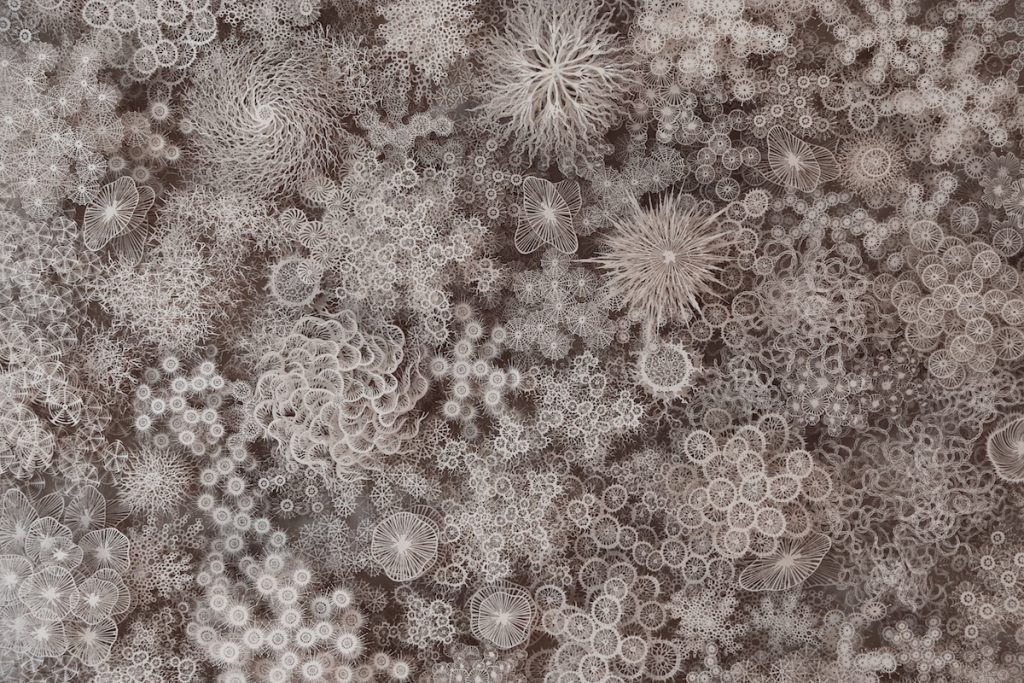

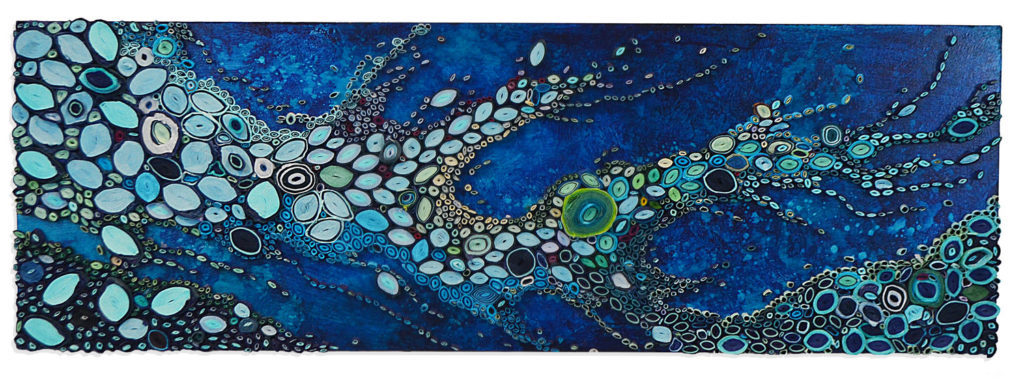

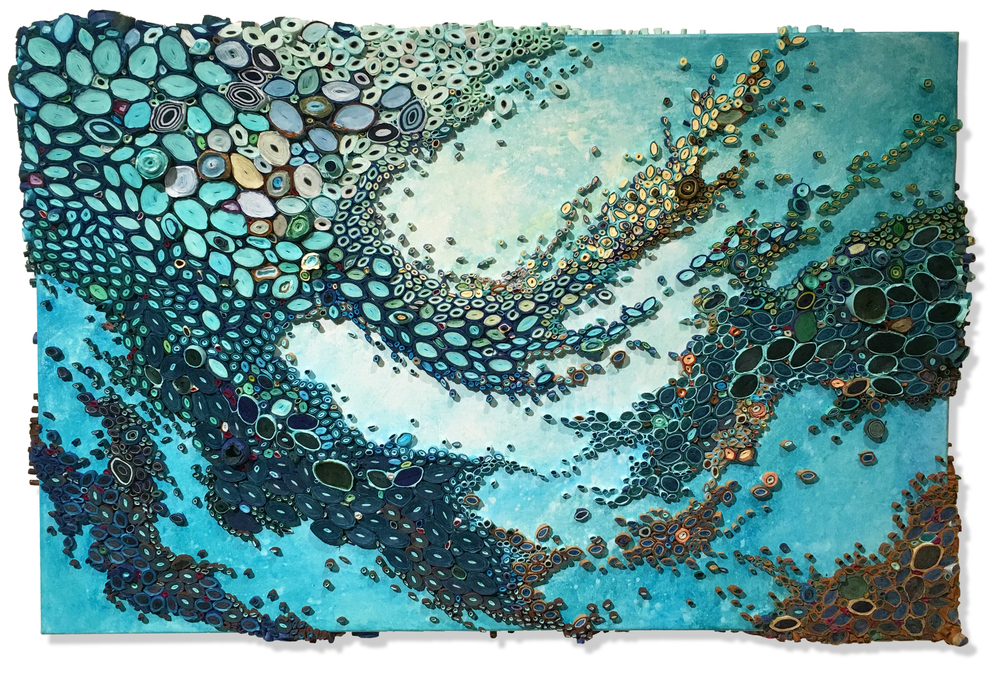

In other works of mine, the goal was to alter viewers negative perception of bacteria” discuss.

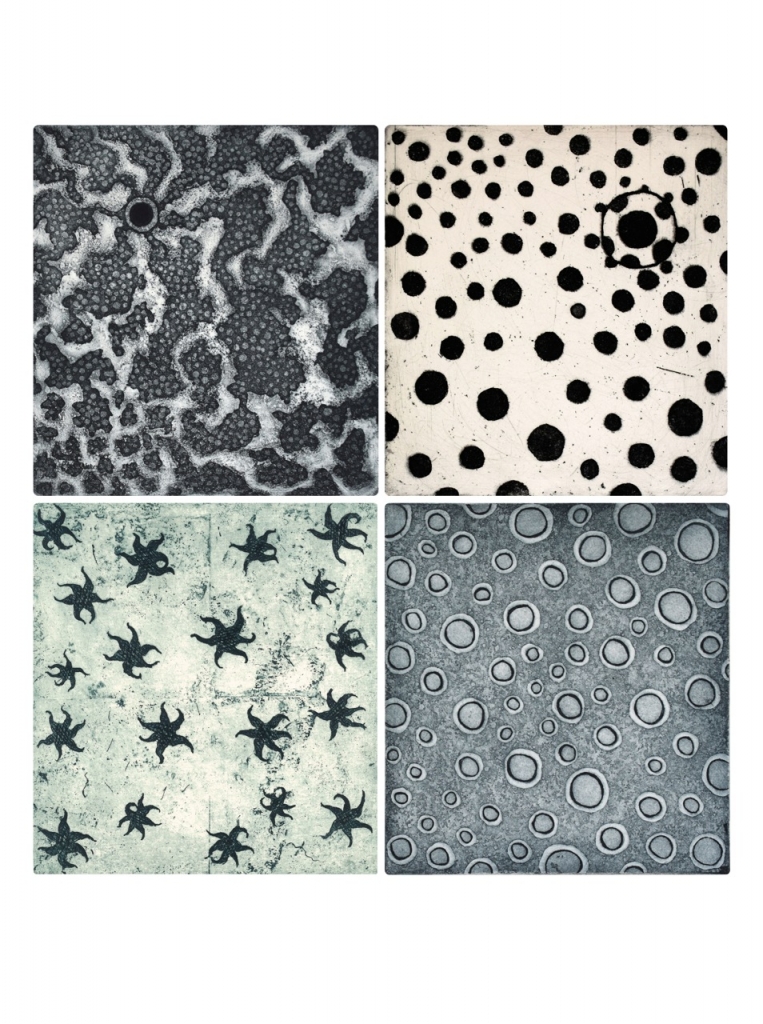

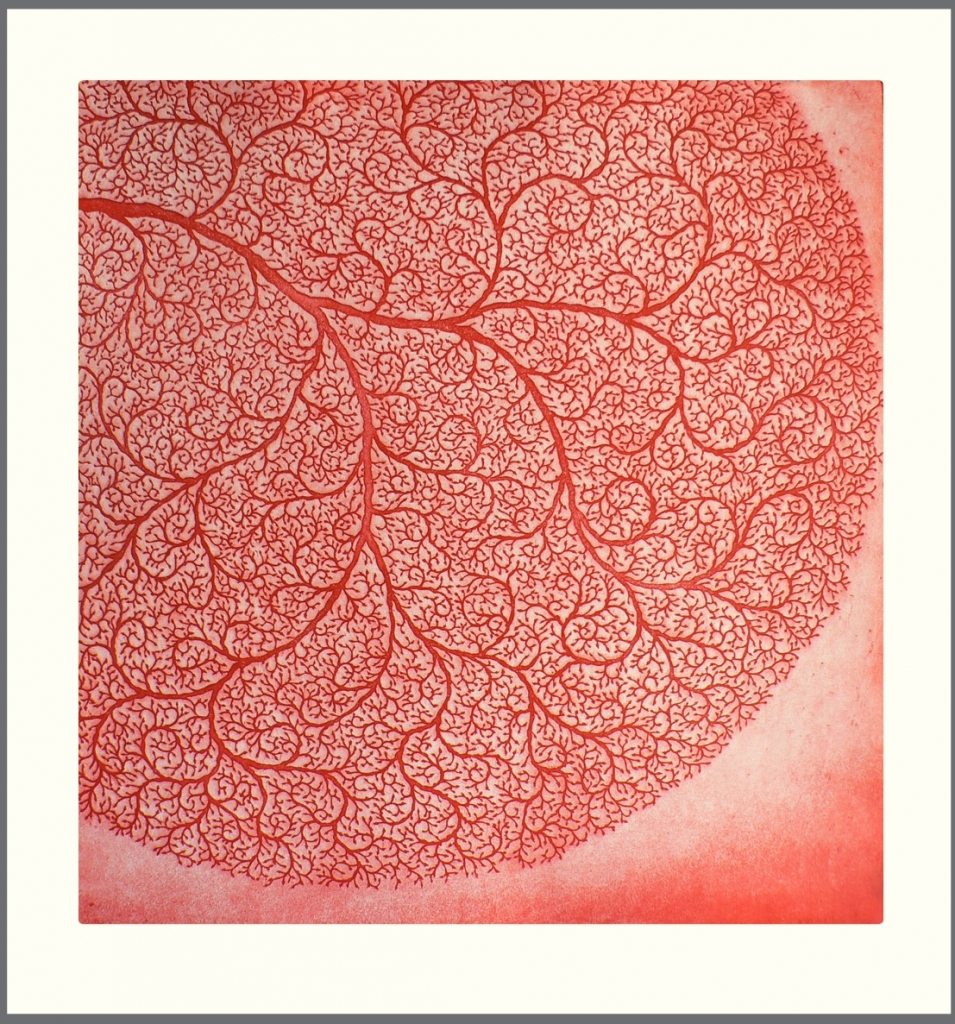

Magic Circle Variation, detail

In the “Magic Circle Variation” series I continue to play with the aesthetics of the bacterial world but here I try to create a visual representation of a bacterial colony. Diverse forms are arranged together in a circular composition that refers to the shape of the petri dish and also to Buddhist mandalas, those intricate sacred images that represent the harmony of the universe. The bacterial colonies that inhabit us are also diverse but work in unison to keep us functioning and create harmony in our bodies. “Magic Circle” is an attempt to communicate that sense of diversity and harmony.

Magic Circle

Give your personal thoughts on collaboration between scientists and artists?

I think such collaborations are crucial; we live in a world dominated by science and technology but sometimes as non-scientists we can feel marginalised, ill-informed and excluded. Artists can play an important role in engaging with science and making it accessible to a non-scientific audience, not in terms of explaining the mechanics of the science but rather by giving a personal, individual response to what is often such a large scale collective endeavour. Art can therefore build a bridge between science and the general public. There are some very exciting but also slightly terrifying developments taking place in science which need to be discussed and debated by the whole of society and not just the scientific community. I'm thinking principally of the development and implications of something like Crispr technology which allows us to alter DNA cheaply and easily for the first time. The ethical issues raised here are enormous but there is little or no public debate about how we should employ such technology. Chinese scientists are already conducting human tests but may be opening a Pandora's Box as they do so...

At the same time I disagree with the notion that the only role left for art to play in society is as a vehicle for exploring socio-political issues. I still believe in the pursuit of beauty as a key driving force in art; but we must look to other branches of knowledge and research in order to find new ways of achieving and expressing that beauty.

Cut Microbe, detail

Contact details:

Rogan Brown

http://roganbrown.com

Rogan Brown, Languedoc, France

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May 2018

Susan McMinn

Explain how you managed to link your PhD to a visit to Israel?

My PhD research was around the horse in war during the Palestine Campaigns of WW1. After researching stories about the Australian war horses concerning their plight during this campaign in the WW1 Light Horse Soldiers diaries, particularly that of Ion Idriess’, and various artworks including paintings by Australian War Artist George Lambert, I realised that I needed to go to Israel to look at and experience the Anzac trails and the landscape in which the horses travelled to understand the topography and hues of the land. Visiting Israel led to an understanding of the land – through creating many small watercolour studies which was important in the development of my paintings.

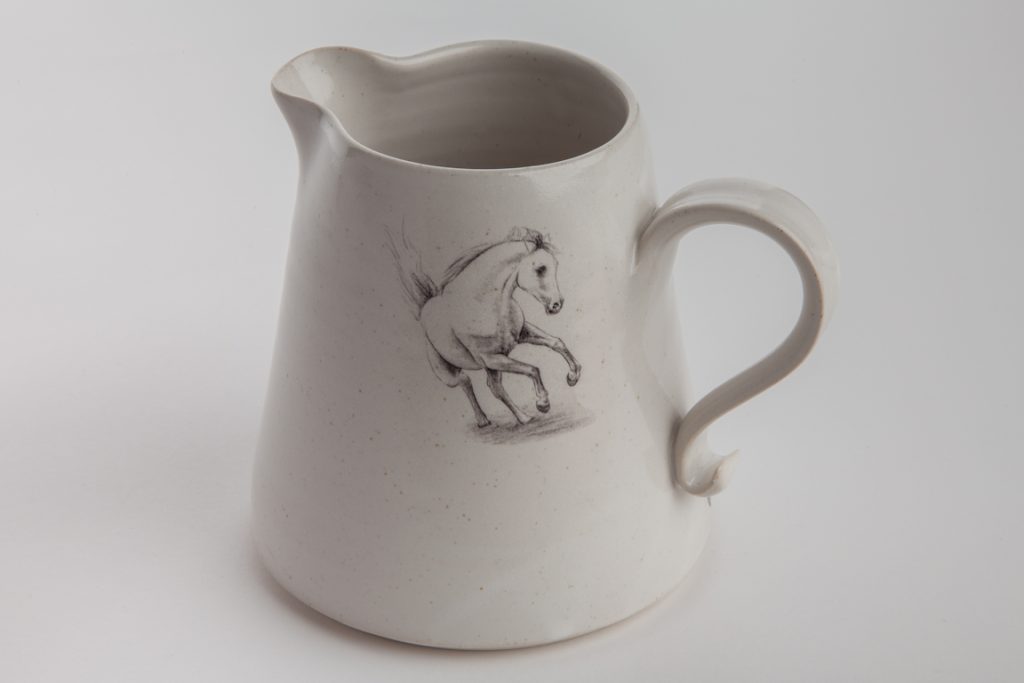

Underslung Horse, Print

When did you first become aware of George Lambert?

I became aware of George Lambert and his work during my PhD whilst researching at the Australian War Memorial. I was interested in the way in which he portrayed the animal in war and his use of colour. I was also drawn to investigating his work as a point of reference to the detailed stories found in the diaries. They gave me a visual compass if you like in understanding where the horses travelled.

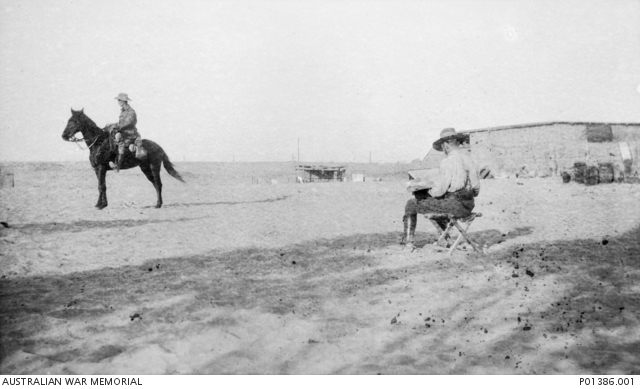

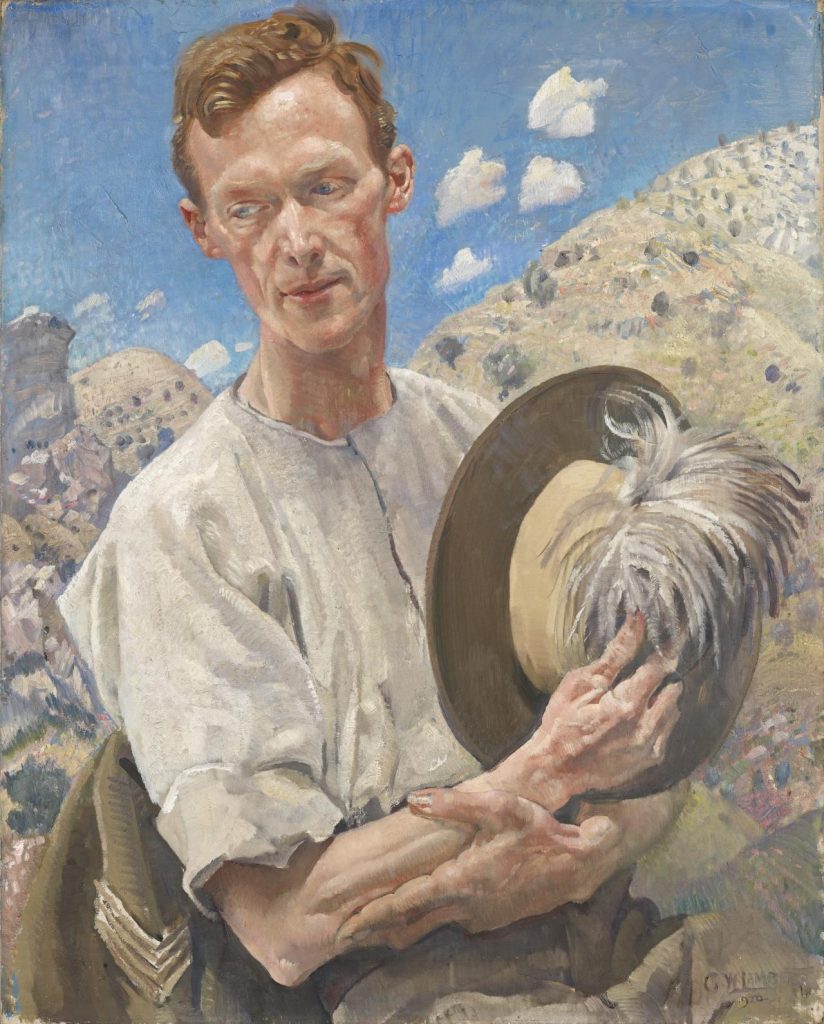

George Lambert work as a war artist in WW1

Explain a little about George Lambert as a War Artist?

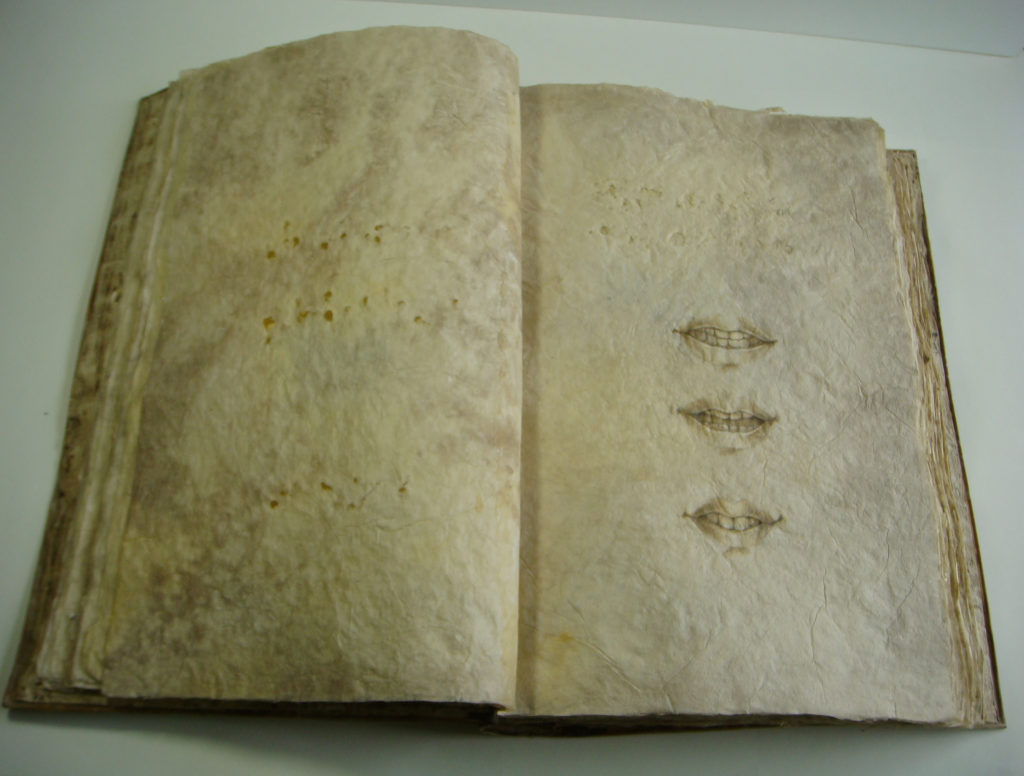

George Lambert and Septimus Power, whose work I also looked at during my studies were both chosen as war artists during WW1. Whilst Power was sent to the Western Front, Lambert was send to Middle East. During this time, Lambert used a visual diary to create small studies of landscapes and figures and animals, from which he created his paintings. He was very concerned with the colours of desert landscape, obvious in his statement regarding the colour of the land, although it could sound outdated, still rings true today. He stated:

A word to those who would paint this country. Leave your gay pigments at home. Approach nature with a simple palette but an extravagant love of form. The sand hills take on shapes and curves, cuts, concave, convex, in an entrancing pattern, interwoven sometimes here sometimes there jagged eccentrically opposed.

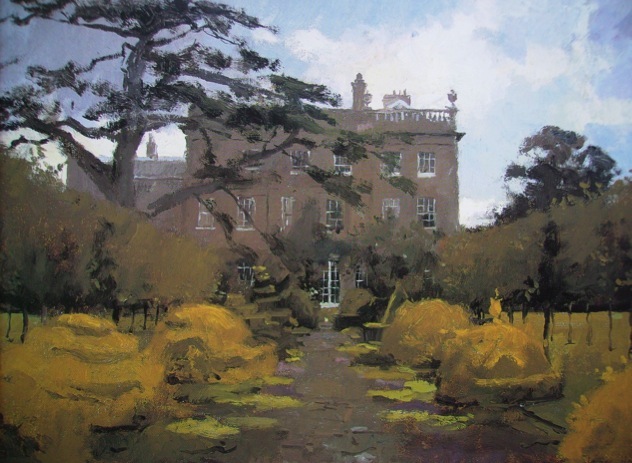

George Lambert, Barada Gorge, 30th Sept. 1918, 1921,1927, Oil on Canvas

My most favourite part about Lambert was that he rode a horse around the country of Israel and arrived at the scene he would paint some weeks after the incident had occurred.

How do current war artists differ from war artists working during the First World War?

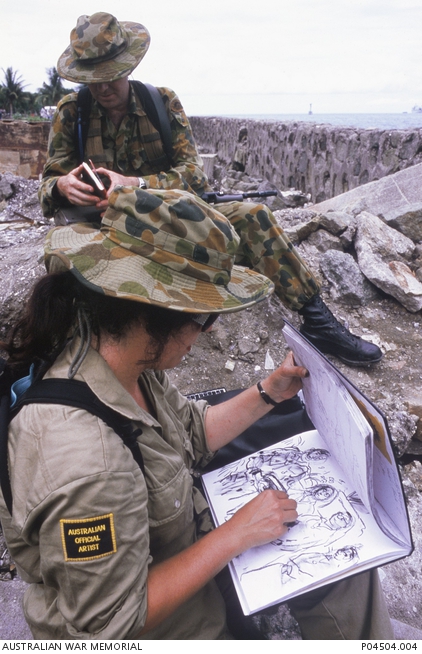

Australian War Artist, Wendy Sharpe.

Current War artists such as Wendy Sharpe and Ben Quilty engage with the soldiers and personnel and perhaps understand the war experience to a greater extend. Their portrayals of war are different in that Wendy Sharpes work created in East Timor captures what she experienced, much like a diary entry.

Whereas as Ben Quilties recent exhibition 'Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan'reaches into the human experience and the absolute gut- wrenching emotions of war.

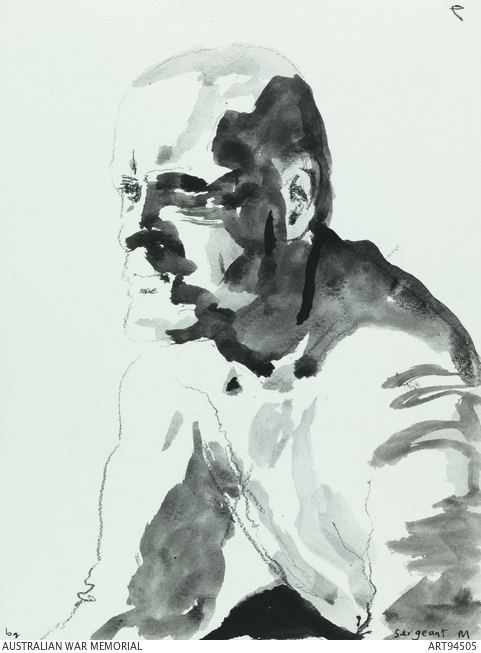

Sergeant M, Special Forces, Tarin Kwot, Ben Quilty

However, artworks by the earlier war artists such as such as Lambert and Power typically represent the harsh war-torn landscape, whilst Ivor Heles work conveys the human struggle.

Discuss George Lambert’s most recognizable WW1 war portrait, ‘A Sergeant of the Light and how it has effected your work?

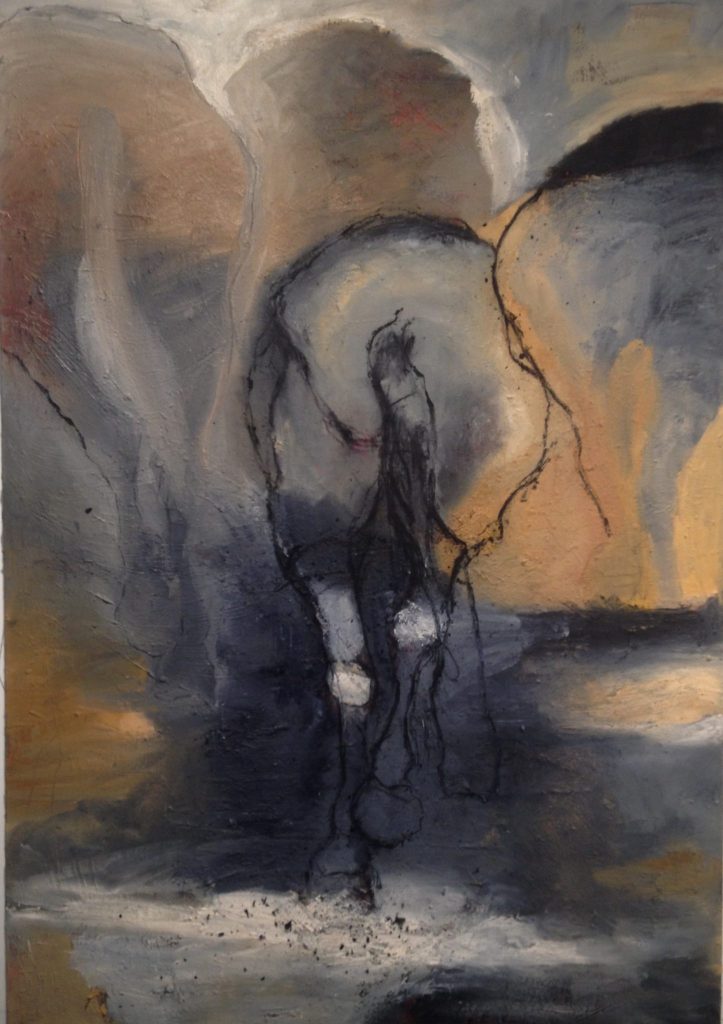

George Lambert, A Sergeant of the Light

My work was based on the Australian horse in war and not so much on the human entity. I try to convey in my work the body language of the horse under war conditions. Because of this I looked at the landscape and the animals that Lambert painted rather than his portraits.

Discuss the landscape of George Lambert Palestine paintings and what you found when you retraced his steps.

The colours Lambert used in his paintings are reflective of the colour of the landscape in Israel. One of the most significant things that the horses and soldiers battled during this campaign was the sand from the Sinai landscape. They often complained of the sand blazing into their eyes. Lamberts work captures this sand in the hazy mauves and muted tones in his paintings. There is a profound contrast between the beauty of the land and its colours, and the harshness of the elements, something which Lambert captures. His impressions of the horse and dead animals are also very poignant. One particular painting Tel El Saba, conveys dead camels and horses, which demonstrates the distorted shape and form shape and form of the carcass. I travelled to Tel El Saba and found the location recognisable because of this painting.

Tel El Saba

Explain the value of retracing another artist with your own impressions and paintings?

I travelled to Israel after I had studied the diaries and lamberts paintings. I found that I needed to then actually look at the landscape myself. I was very surprised that some of the Landscape that Lambert had painted was identifiable. I made a lot of watercolour sketches and then when I returned back to my studio in Australia, I completed a series of landscape paintings whilst the colours of the landscape were still visible in my mind. When you are studying and painting a period of history all you have to rely on are the Archival and personal stories, past artworks and photographs.

Bir sluj

Can you discuss the honour of your upcoming Exhibition, Battle of Beersheba, Historical Memorabilia and Contemporary Artwork?

I am very thrilled to have my work exhibited alongside that of Sidney Nolan and George Lambert. Especially since I have studied their work in relation to my PhD studies. I also studied Chauvel’s letters to his wife which I found very moving. I feel very honoured to be part of this exhibition.

What does it feel like to be exhibition with such renowned Australian Artists?

It is amazing. It is like my PhD research is on display at the Shrine, having studies each of the artists works and the letters written by Chauvel.

When did you first start of paint horses?

I started painting the horse during third year of my fine arts degree at La Trobe University. During this time my paintings investigated the charge of Beersheba. As I was an avid horsewoman I used my understanding of the shape and form of the horse to create works. I also went to a small farm in Bendigo and drew horses onsite within their environment.

Expand on your word, ‘Horstory’?

The term Horstory is a play on the words horse, narrative and history.

Can you expand on your 2009 animation, ‘The Last War Horse’?

My work was very focused on movement and I was fortunate to win an animation bursary to create a three minute hand drawn animation. This work loosely reflects the following:

During the Palestine Campaigns of WW1, Australia sent approximately 130,000 horses to the Middle East. During war service these horses suffered night treks of up to 90 miles at a time, carried weights beyond their normal capacity, died of exhaustion, suffered thirst and hunger, were shot, blown up and finally the remaining horses were left in the Middle East at wars end. Companion, Soldier, animal in service. The Australian horse is 'The Last Warhorse', depicted in this three minute charcoal hand drawn video.

The Last Warhorse won the best Australian Student film at the Australian International animation festival and was the only student film shown during the WIFT (women in film and television screening) and can be seen in the permanent collection of the Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance.

What lead you to do your PhD in Fine Arts?

I started studying art later in life in my early 40’s. I completed my degree with honours and decided to go onto study a Master’s degree focusing on the horse during WW1. On advice from my then supervisors and I upgraded to a PhD due to the sheer volume of work and research that this subject matter generated.

Morry and Stan 2016 < Oil and mixed media on canvas - 6'x 4'

You use colour very strongly, and in relation to the environment, discuss.

The colour I use is representational of not only the land where the horses travelled but also where they fought and died. In addition, the paint and materials including sand are thickly layered. It was as if, during the painting process painting, that I subconsciously released the horses back into the landscape by etching their form into the rich textures and tone.

Bloody Night, March 1

Does living in the country strongly effect your art and the themes you work on?

I now live in Bendigo however I grew up in the small dairy farming area of Ballendella, 1 hour north of Bendigo. It wasn’t always easy. I guess growing up in the country effects my art in that I am fairly pragmatic and I have a very strong work ethic. Therefore, I am attracted to themes that are tangible and possibly connect with Australians who have endured difficulty to some degree. My relationship with the horse certainly incited an interest in the story of the Australian horses that went to war. I used to ride my horse to my friend Kathy’s house on the weekends some ten miles away from my home, and I often recalled this experience when I read about the horses carrying the soldiers for miles as they travelled through the night in Palestine.

The Desert March, Mixed Medium on canvas

Discuss some or your other current art work?

My current work involves explorations into technology and the use of digital technology, word and painting. I have been completing digital paintings that relate to one word. They are lots of fun and the colour is very vibrant when printed.

I will also be undergoing a new project with the Bendigo RSL. I will be researching the Victoria collection and looking at notions surrounding the war vets and families return from war.

I will create a body of work that will be exhibited at the new Bendigo RSL Museum Gallery in 2019.

Rising Sun, Lest We Forget, ANZAC Day 25th April

Contact details:

Susan McMinn

Susan McMinn, Bendigo, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2018

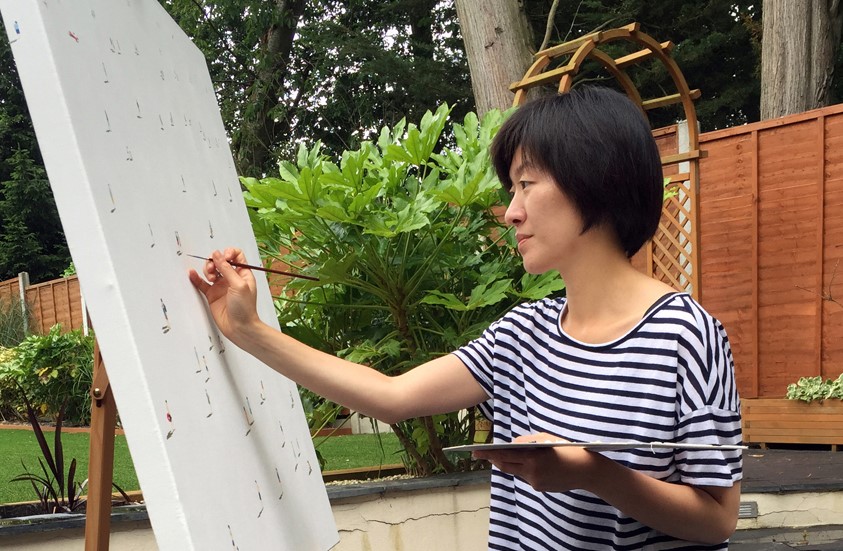

Stephanie Ho

Can you discuss your style and the style of Lowry?

People often said my works reminded them of L. S. Lowry, an important English painter in the mid 20th century, famous for his landscape peopled with human figures.

Lowry's works represent life in the industrial district of England while I have chosen metropolitan city lives as my subject.

There's a lack of weather effect in Lowry’s works so no shadows are used to represent light. On the contrary, weather plays an important role in my works. The use of shadows is an essential tool in my works to represent time, location and movement.

The crisp white background of my paintings gives a more uplifting, happy feeling, compared to the more melancholic atmosphere of Lowry’s work.

Lowry is only one of the many artists that I admired. My works are also inspired by contemporary artists such as Gerhard Richter, Julian Opie and Alex Katz.

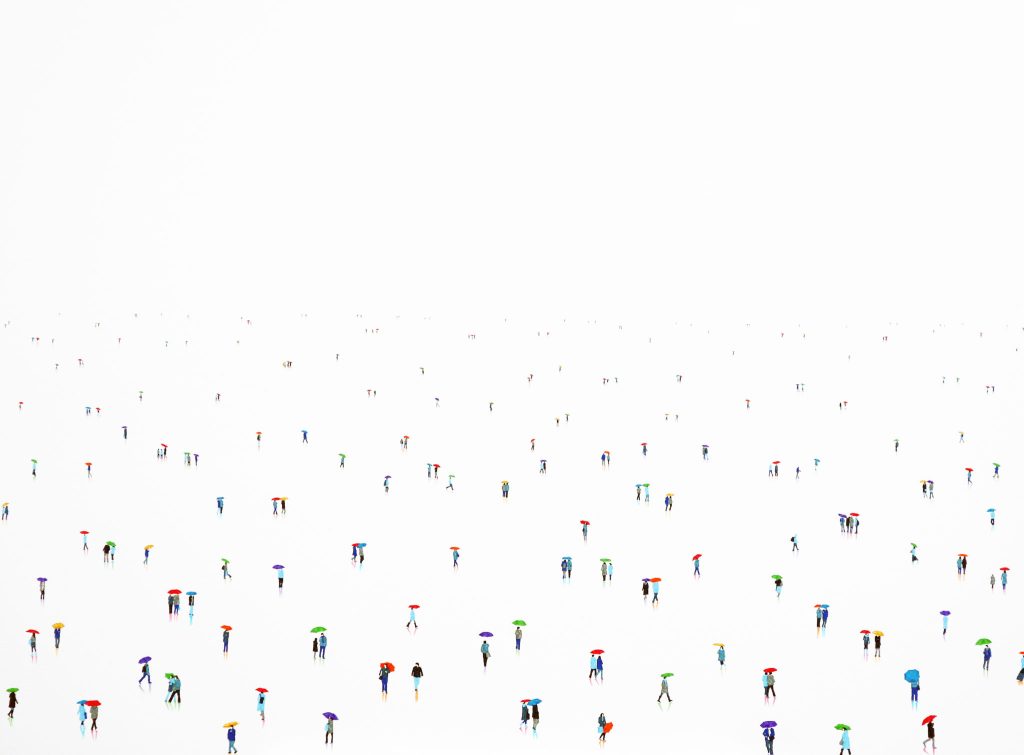

Rain - Bow, 11, 90 x 120 cm

You have taken part in many exhibitions discuss the importance of exhibition to the growth development of your work?

Social media is now playing a large part in showcasing artworks. However, I do enjoy visiting exhibitions, especially being present at my own shows and art fairs. It is a great way to communicate with other art lovers.

I believe conversing directly with spectators can give the artworks a different dimension, they will remember not only the picture, but the story and inspiration behind as well.

I also take this opportunity to find out what people think about my work. Listening to comments help me improve and develop new theme and style.

You have a degree in Museum and Gallery Management, how has this background helped in your art career?

My Museum and Gallery Management degree is actually my stepping-stone to becoming a full-time artist.

I talked to a lot of gallery owners, curators and critics during the course of my degree. They have given me an insight to working in the contemporary art world and make me appreciate the hard work that galleries put into behind a successful exhibition.

I realised that I enjoy creating artworks much more than promoting other artists’ work and organizing exhibitions.

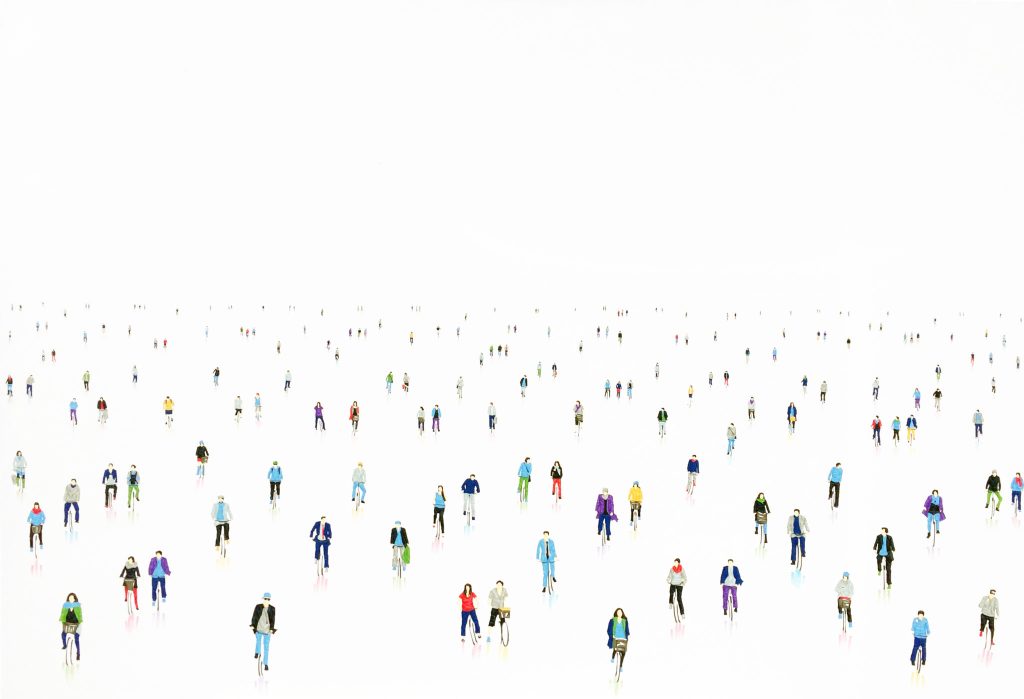

Derby 01, 90 x 90 cm (earlier work)

Discuss the use of shadow in some but not all your work.

The Still Frame series, my earlier works, are inspired by postmodern art and artworks by Chinese contemporary artists, the colours in this series are more vibrant; figures are more repetitive and distributed evenly across the canvas like a pattern. That's why I feel shadows are unnecessary.

The introduction of shadows in my later series, Human Planet, enhanced the reality of space, time, location and motion. It gives life to the paintings, bringing them to a new dimension.

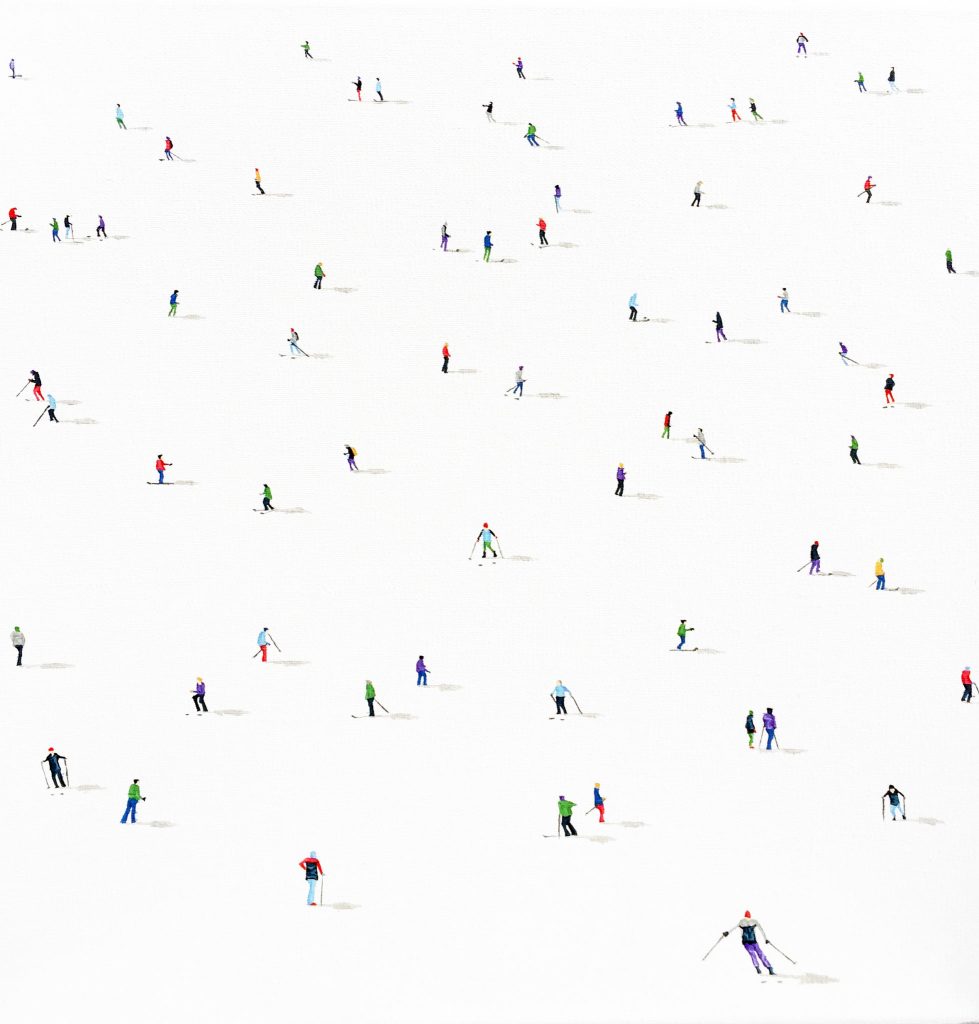

Frozen Planet 29, 100 x 70 cm

Frozen Planet 29, 100 x 70 cm

Your comment, ‘Just like composing a piece of music, with notations hanging across the lines, creating melodies, conversing with the spectators.’ Discuss.

I believe paintings and music are both art forms that converse with the spectators in their own very special language. From afar, the tiny figures in my paintings look like small dots on an empty sheet. The process of placing figures carefully and precisely on the white background resembles the composition of a beautiful piece of music.

2 Wheels 03, 70 x 100 cm

How does weather effect your work?

The changing seasons and weather play an important role in my works. I use colours and shadows relating to the weather to portray the behaviours, moods and activities of the people in the painting.

I purposely leave the background colourless so the viewers can have the freedom to fill in the missing information.

Frozen Planet 20, 30 x 30 cm

Can you expand on the techniques you use in taking the painting right around the canvas to the sides?

Also, the placement of your signature on you work?

Painting right around the canvas to the sides can give my artworks continuity and life. I want my viewers to look beyond the obvious, not restricted by the size of the paintings. They will be surprised how much more there is to discover.

Putting my signature on the side will allow viewers to concentrate on the composition of the painting initially. In order to discover the artwork’s identity, they have to get close to the work and look into the details.

Frozen Planet Nano 19, 12 x 12 cm

Contact details:

Stephanie Ho

stephaniesyho@gmail.com

www.stephaniesyho.com

Stephanie Ho, London, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2018

Jess Dare

How did you get from playing in the yard with berries and bugs to interpreting them in glass?

There are more than 25 years of experiences, opportunities, adventures, misadventures, love and heartbreak that fuel the answer to that question.

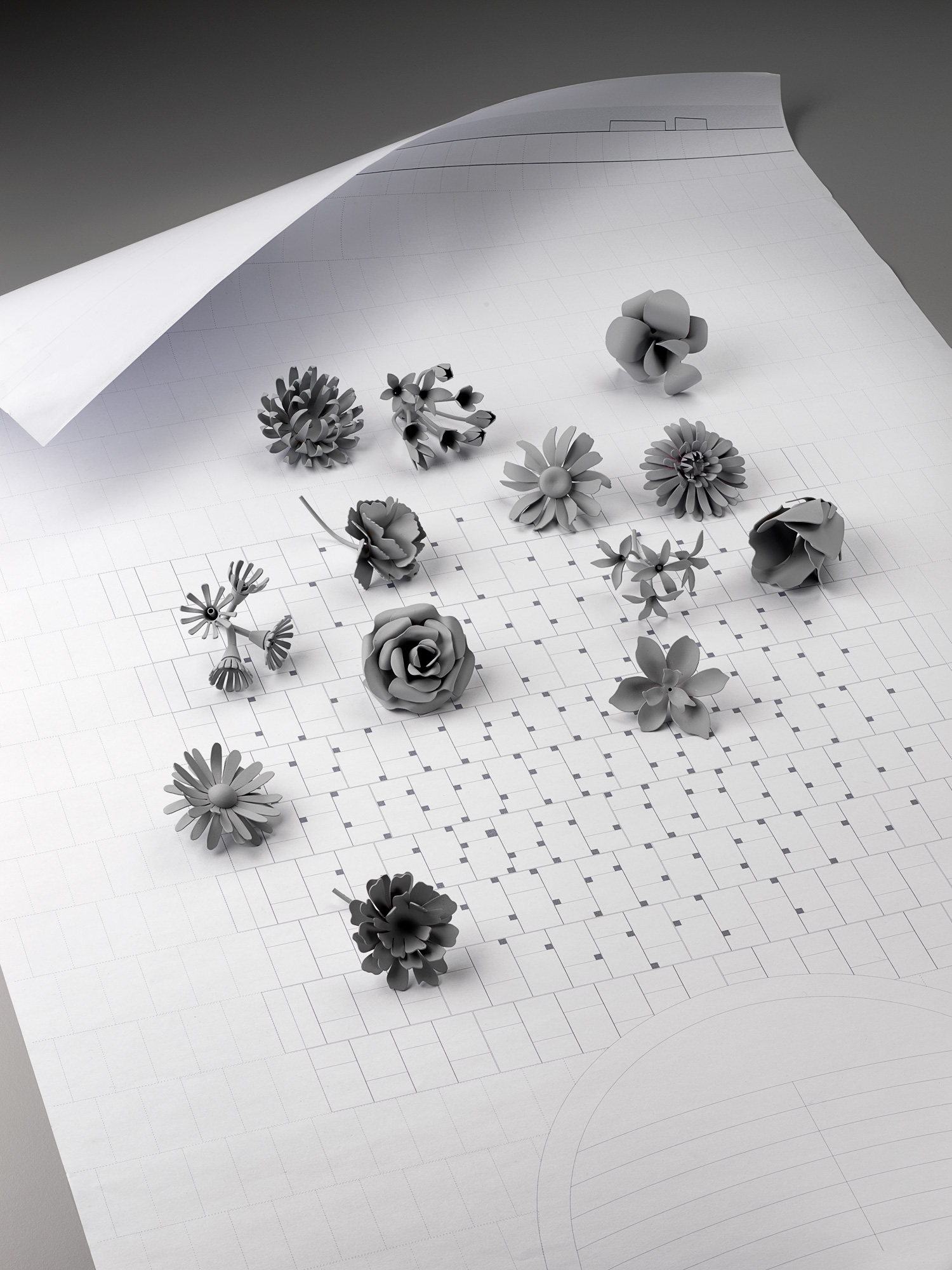

Conceptual Flowering Plant Series, 2013 Flamework Glass, Photo Grant Hancock

But the impetus behind creating my first major collection of glass plants in 2013 was the passing of my dear Grandfather, Dean Hosking. He was an incredibly passionate gardener and after he died in 2011, everyone in our family became passionately obsessed with their gardens. It was as if they were returning to the earth to be close to him. This collection of glass plants became my garden, in reflection it was a very cathartic, healing process.

Conceptual Flowering Plant Series, 2013 Flamework Glass, Photo Grant Hancock

Explain about your residency in Bangkok, Thailand, in relations to their national floral garlands?

In 2014 I was granted an Asialink artist residency in Bangkok, Thailand, supported by Arts SA and hosted by Atelier Rudee, International Academy of contemporary jewellery. The main objective was to learn the traditional craft of Phuang Malai (floral garlands) and to translate this into my work using glass and metal. Phuang Malai is traditionally an ephemeral craft using flowers strung in different patterns and formations for different meanings and occasions.

I was initially drawn to this craft as it is used to honour “seen and unseen beings” alike, echoing the themes of memory and honouring past loved ones that is core to my exhibition work.

Lesson in Pak Kret: showing elements ready to assemble. Hand dyed orchid petals, crown flower, Jasmine. Photo Jess Dare.

My residency took me all over Thailand, from moulding cow dung in a remote village in the province of Ubon Ratachathani to casting bronze bells the same way that has been done for over 4000 years, to working with delicate orchids in the Museum of Floral culture. Threading hand-cut leaves in Pak Ret. Planting rice, ‘back to the sun, face to the earth’. To holding up Traffic on a photo shoot in the streets of Bangkok. Even a short week-long residency with famed ceramic artists Wasinburee Supanichvoraparch in Ratchburi at his family’s ceramic factory, Tao Hong Tai.

First traditional Phuang Malai I made using Jasmin, Crown flowers, Amaranth and Magnolia. Meaning: Never ending love. 2014, Photo Jess Dare

The residency, the experiences I had and the people I met, opened a new world for me, a rich source of inspiration, a new way of working and thinking about my work. I feel like the experience will feed my practice for many years to come. I actively chose to expand my vocabulary and my practice by travelling to another country to experience new skills and way of making, immerse myself in another culture. And I would encourage anyone to undertake an artist residency, to extend your physical borders, push your personal boundaries and comfort zone, challenge yourself, question your making, explore the unknown and then see what happens next….

Explain the importance of Garlands throughout the world?

Yikes this is a huge question! I can only speak from the experiences that I had in Thailand and by no means am I an authority on Garlands.

There are several shapes and styles of Phuang Malai with a variety of functions that fall in to the 3 main categories: offering, decoration and gift. The functions range from offerings to Buddha or for hanging around the neck or the wrist or to hold in the hand, to being tethered to boats, cars and buses for a safe journey home, there are types for ceremonies like wedding and funerals, whilst some to simply hang in the windows of houses for scenting the breeze with jasmine. I was particularly interested in the role that they play in paying respect, and as offerings.

Offerings at Erawan Shrine, Bankok, 2014, Photo Jess Dare

I love Phuang malai, I appreciate them aesthetically as well as sentimentally and spiritually but if people are interested in reading more about garlands I would highly recommend the Garland website (www.garlandmag.com) where you will find articles about the stories behind what people make alongside numerous articles about garlands and leis from all around the world.

Personally, I feel that they break down barriers, if you have ever been given a garland perhaps you will share this sentiment. I have always felt humbled, a tradition steeped in rich history, something hand crafted, especially the Phuang malai of Thailand made of fresh flowers which are literally wilting as they are being strung, they are not meant to last, they are meant for just a moment.

Explain the meaning of flowers and how this effects your work?

Flowers mean different things to everyone. Historically there is a rich language, symbolism and meaning of flowers. And whilst sometimes I reference these traditional meanings I am very much a sentimental gardener and maker, so I often use flowers which have a personal significance to me, for example the Magnolia. This is a flower that comes up time and time again in my life and also my work. It is one of the last trees I planted with my grandfather, it is used often in Phuang malai at the base of the uba and is the floral symbol of Shanghai where I did a residency in 2015.

In general, I use flowers as a metaphor for the transience of life. To me flowers are a constant reminder that life is ephemeral, ever-changing, momentary and precious.

Wilted, powder coated brass, stainless steel cable, sterling silver, 2016

Photo Grant Hancock

Can you expand on the Jean Francois Turpin’s conceptual flowering plant of 1837?

Turpin’s Conceptual flowering plant of 1837 was a type of teaching aid popular in the 19th century. It depicts an imaginary plant that incorporates the characteristics of many diverse flowering plants, with various kinds of stamen, leaves, stems, bulbs, tubers and even leaf gals.

The series of glass plants I created in 2013 entitled conceptual flowering plants were plants drawn from my imagination and my memory of plants, they incorporated elements of different plants and yet they still felt familiar. I loved hearing people point out different plants and vehemently explain that that plant was a lavender or a snowberry etc.

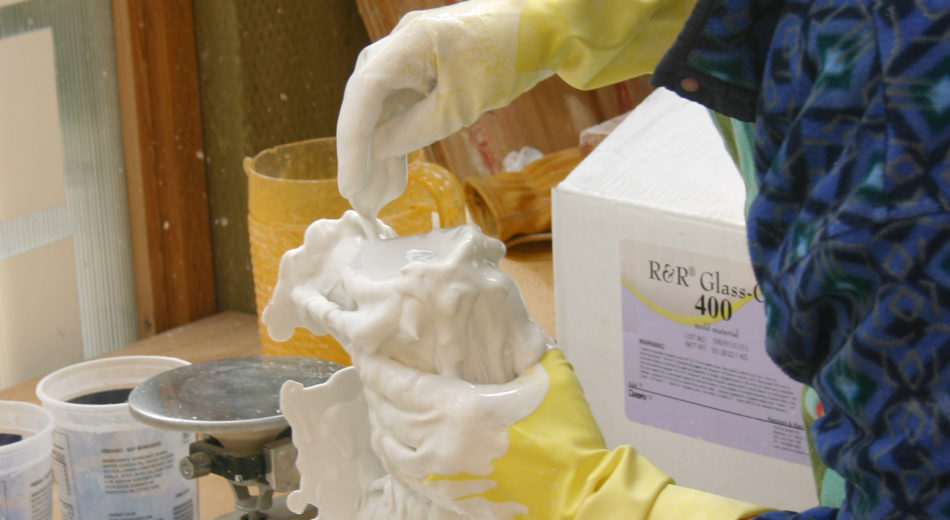

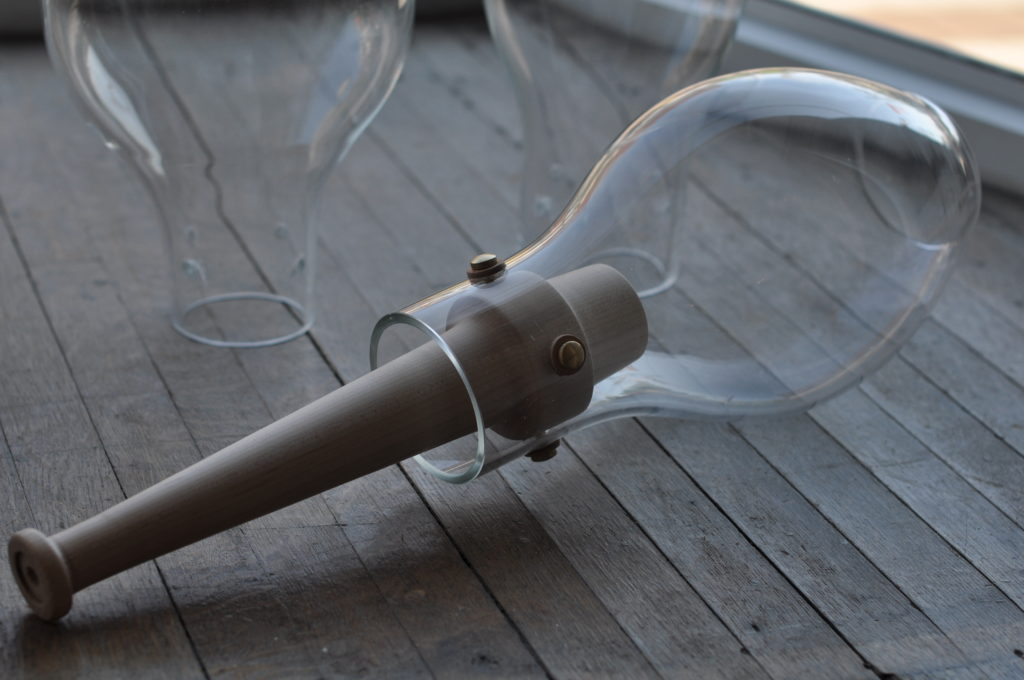

Please give a brief explanation about the technique of lampworking and how you use it in your work ?

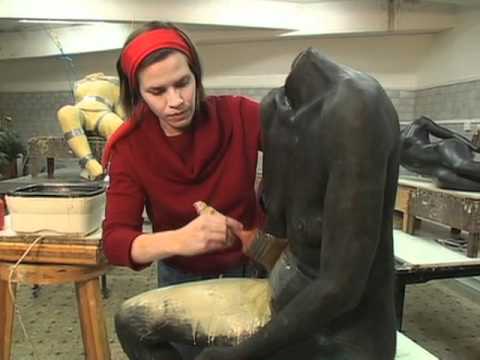

Flameworking demonstration, photo Annalies Hofmeyer

‘As a jeweller I have always been drawn to the miniature’ discuss this comment.

As a Jeweller I work on a very small scale, generally working in a zone no more than 300mm from the tip of my nose. It's a small field, it is a private, intimate space, my own little world.

I am drawn to the minute details of things as it’s the scale that is familiar, comfortable.

My fiancé finds it infuriating to go for walks with me as I am always one hundred steps behind him, taking photos of little things, little details, plants etc I find along the way.

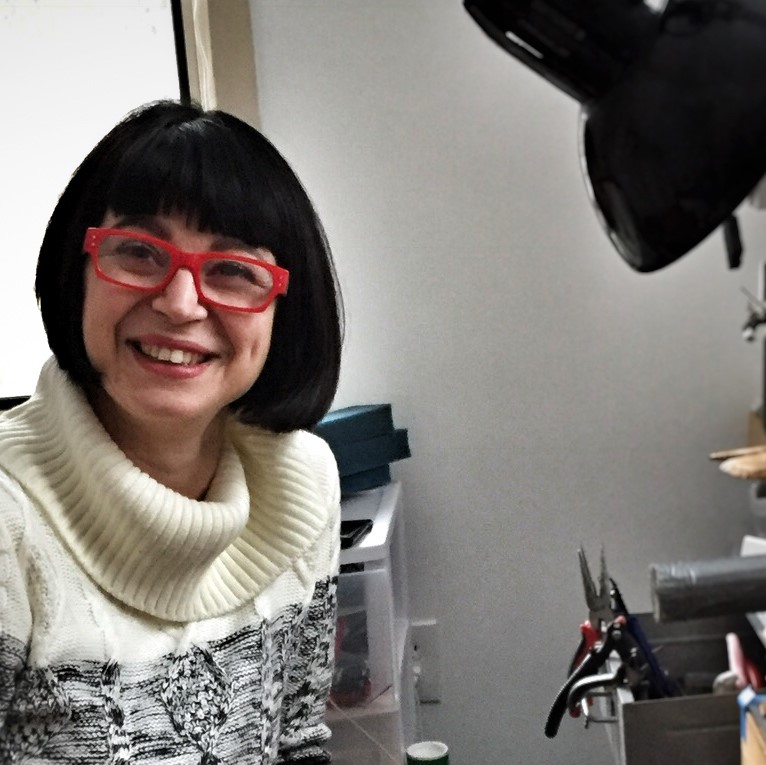

Working at the bench, photo Jessica Clark

Discuss your involvement in the memorial for the 2014 Martin Place siege?

Flowering Gum, photo Grant Hancock

I was approached by Professor Richard Johnson AO who designed the memorial to develop a concept for the flowers which would be housed in the mirrored cubes to be inlaid into the paving of Martin Place. After intense research I then designed, and hand made all the brass flowers.

Initial flower models, Grant Hancock

Why are there 210 flowers in this project?

The 210 individual flowers represent the sea of flowers that filled Martin Place in the days and weeks following the siege in December 2014 and capture the carpet of colour and movement of the more than 100,000 bunches. They reference the community’s spontaneous outpouring of grief and compassion in the aftermath of the siege.

The centrepieces of Reflection are a cluster of 5 aqua hydrangeas and another of 5 yellow sunflowers, memorialising the two bright young Australians tragically killed in the siege, Katrina Dawson and Tori Johnson.

200 flowers are arranged in a Starburst pattern radiating out from these two central clusters to form a circle, a field of flowers.

Reflection, Martin Place, 2017, photo Brett Boardman

The 210 flowers are made up of 12 varieties in 19 different colours. Each flower is unique, each cut and formed by hand, creating all these beautiful nuances, little variations, a slightly curled or ruffled petal a bend in the stem etc. Inviting people to spend time looking at individual flowers and exploring their subtle variations.

Reflection, Martin Place, 2017, photo Brett Boardman

In two of your series, you use wilting and waning flowers, can you expand on this?

In Thailand I began photographing decaying Phuang Malai that I found in the street, their intended destination unknown to me, perhaps dropped, offered to a spirit house or temple, or strung on a car rear vision mirror. I was intrigued by the brilliant coloured ribbons and decaying, browning petals, flattened by passing traffic, shrivelling in the heat and wondered had these objects reached their intended destination? Someone took care to string these delicate petals and crown flowers together. I marvelled at the journey these objects had taken and what brought them to this place.

Decaying Phuang Malai, Thailand, 2041, photo Jess Dare

The wilting and waning series of flowers are made of brass, powder coated and scratched back in parts. The colour white references decay, hastening the passage of time, alluding to the disintegration and sun bleaching of the once brightly coloured flowers. After a Phuang Malai is offered it will eventually decay leaving behind only the act of offering, these enduring objects represent this passage.

When you sell a piece for example, from Epicormic and Xylem Series, does you work come with a botanical explanation?

No I don’t provide a botanical explanation, some of the galleries I sell my work in provide an artist statement and of course if anyone asks I am happy to provide that information but I don’t like to over explain work, the titles and artist statements hint at its meaning but I think it’s important for the viewer or owner in some cases to have the space to bring their own interpretation to the work.

You also work with leaves and petals, discuss this in relationship to colour?

I work with all parts of plants, roots and internal structures.

In terms of colour I have been increasingly using white and clear bleached of colour to suggest transience in the way flowers wither, loose colour and die.

Most of your work is very fine and detailed, expand on the importance of ‘less’ in your work?

Actually, I think my glass is very fine, delicate and detailed but my metal pieces are often very minimal, reducing organic forms to more geometric simplified forms.

I choose the material that best suits the concept I am working on or trying to explore.

Offerings: Elementary Phuang Malai, brass, copper, cotton thread, 2105, photo Grant Hancock

In terms of ‘Less’, A mentor of mine once said “the art is knowing what to leave off”. I often think about those words, less is more, leave room for the viewer to bring their own interpretation, don’t over explain both literally and visually, I think hints can be more powerful that the glaringly obvious.

Contact details:

Jess Dare

jessdare@bigpond.com

Jess Dare, South Australia, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2018

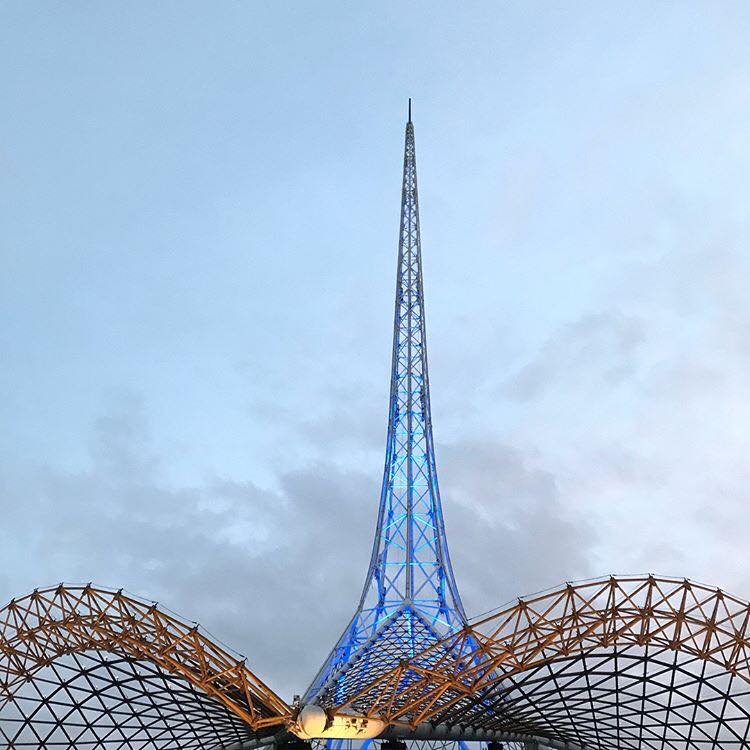

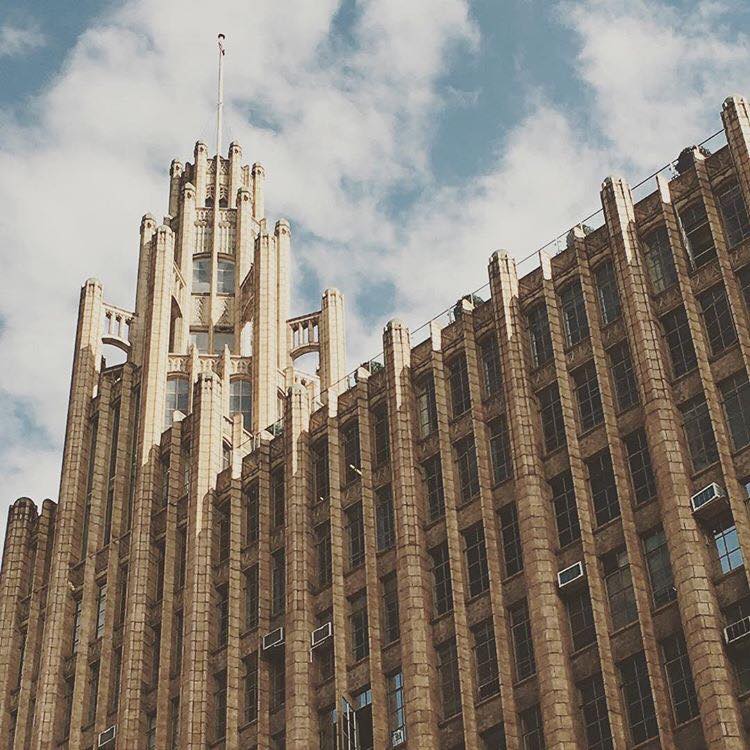

The Melbourne Map

Melinda Clarke

Can you tell us briefly of the history of the 1st Melbourne Map?

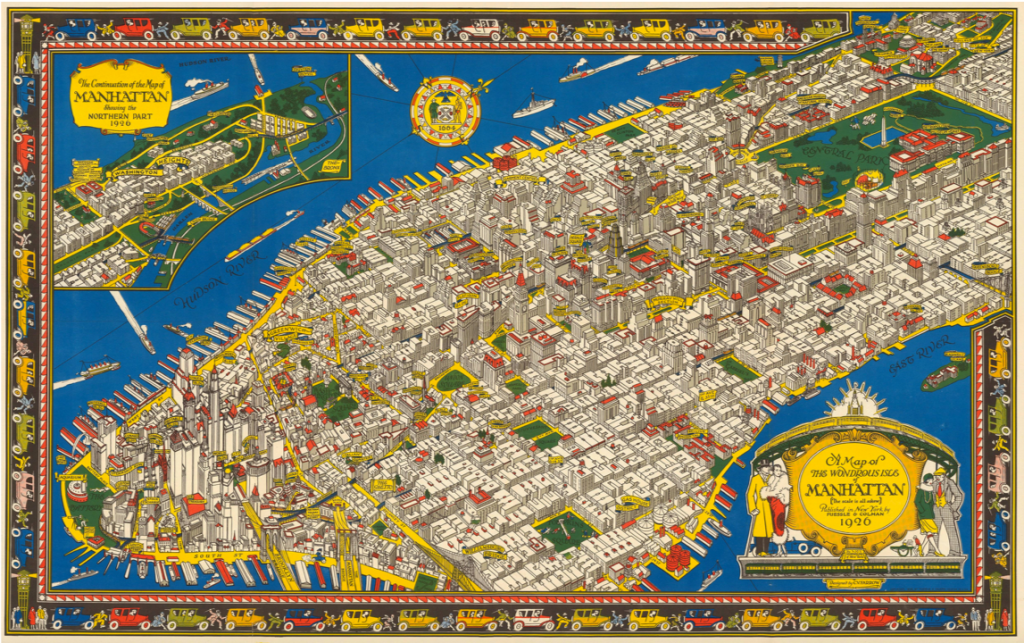

Original: In my mid 20’s I headed off to explore the world and spent a couple of years backpacking around Europe and the USA. Along the way I collected some fabulous illustrated maps and upon my return to Melbourne I searched for one of Melbourne. The only map I could find was a beautiful illustration by A.C. Cooke, later engraved by Samuel Calvert for inclusion in the Illustrated Australian News in 1880.

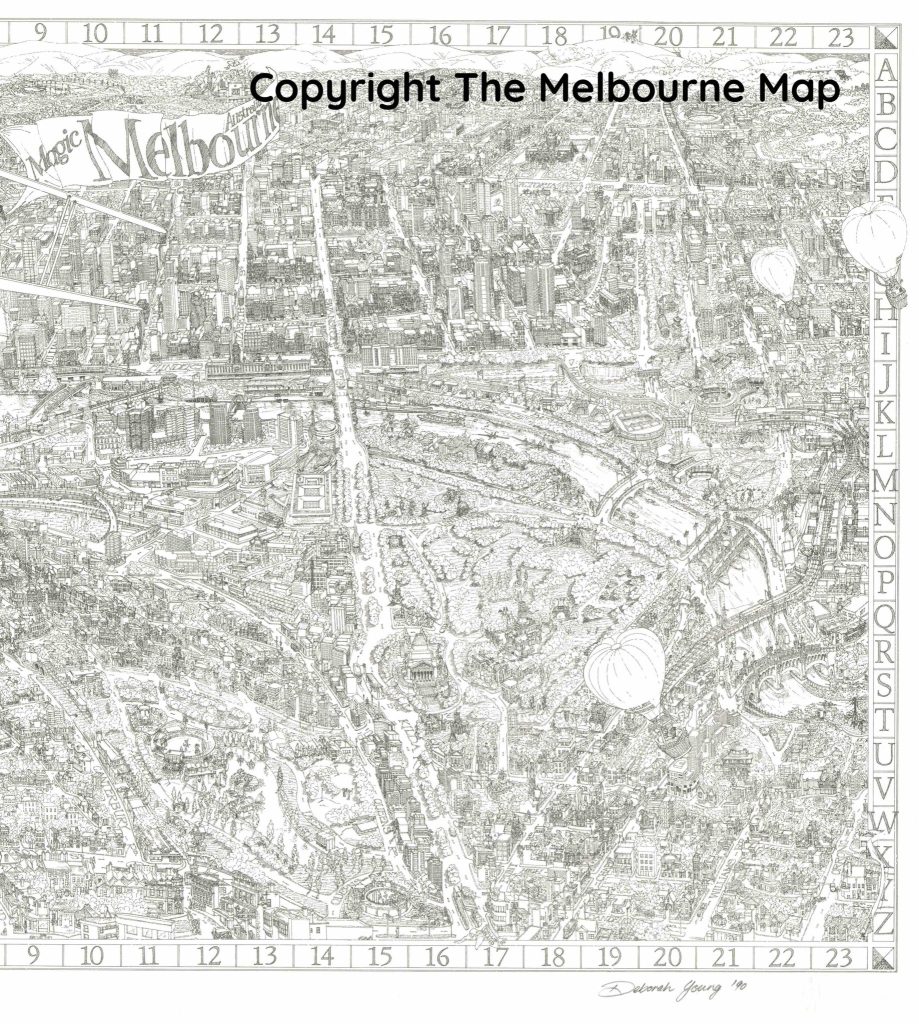

I put a business plan together based on the idea of producing a modern illustrated map of Melbourne and searched for an artist to collaborate with. As serendipity would have it I met Deborah Young through a friend and we worked at nights and weekends from a converted garage at the back of my mother’s house. Over 7,500 research photos were taken and developed, many from a hot air balloon. It took us over 4 years to complete the research and illustration and eventually I took out a $50,000 loan with the ANZ bank at 22.5% interest so Deborah could leave her full time job and complete the drawing.

Once the line drawing was finished it was printed as a limited edition print of 1,000 on to archival rag paper and we went about selling the prints at $250 each.

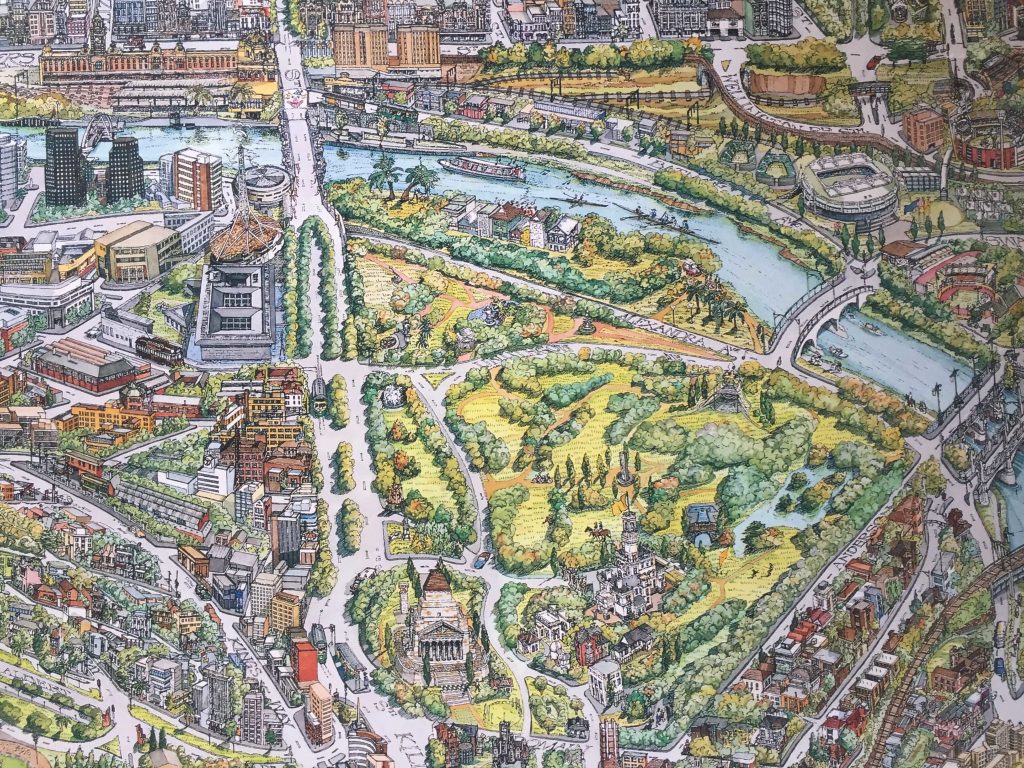

Coloured

A year later two other artists joined the project (Heather Potter & Mark Jackson) who made some updates to the original drawing and a limited edition of 25 was screen printed by Larry Rawlings. One of those prints was then meticulously hand coloured (watercolour) referring to the original research photos. It took 8 months to complete this stage.

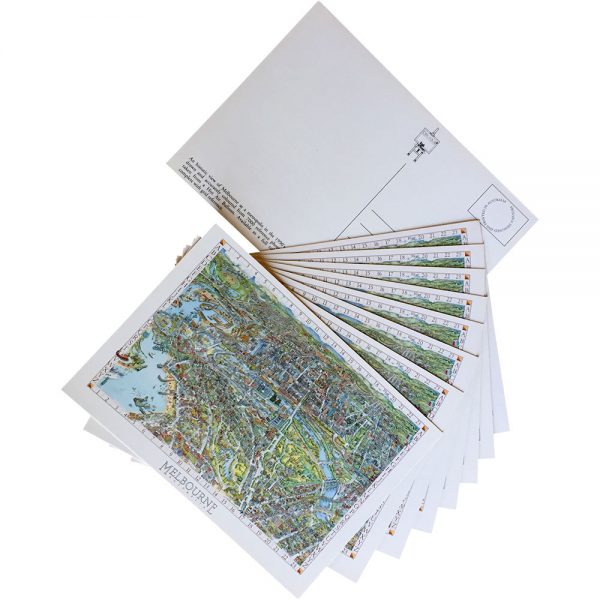

I printed and marketed a full colour poster in several sizes, a jigsaw puzzle, gift cards and post cards.

It was an extraordinarily popular image, made even more intriguing as people poured over the “Can You Find?” list and tried to find all the buildings, transport, people and events included in the illustration.

The whole team had such a great experience creating The Melbourne Map and I think this transferred on to the illustration and to the end user. The map appealed to all ages and adorned the walls of homes and offices here and abroad.

What lead you to do a second Melbourne Map?

It was a multitude of things the seed was set when I made a decision to clear out the back shed which housed all the photos and memorabilia I had stored for 25 years. Instead of moving and discarding I found myself pouring over all the photos and journals I had kept of sales.

I did a quick search on the internet to look for any new maps of Melbourne. Not only could I not find any new maps, I couldn’t find any images of our Melbourne Map so I took some photos of the print and shared them on pinterest, facebook and Instagram. The response was amazing from people who loved the first map and for some insane reason I contemplated producing a new one.

I wrote another business plan entailing considerable research and financial planning and spent a year gathering information on new technology, setting up a website and social media, talking to “Melbourne” people and businesses and contemplating the mammoth task ahead.

Briefly discuss how you have funded the second map?

Whilst still having employment I took out a loan against my home. Having exhausted this first $100,000 I then produced a crowd funding campaign which has enabled us to gauge the popularity of The (new) Melbourne Map, pre-sell copies and share the map making process with our supporters. Raising these funds has also enabled us to meet the ongoing costs of the completion of the artwork which is due for release later in 2018.

We will print giclee Limited Edition prints in two sizes which will be numbered, embossed and signed by the artists (black & white and colour versions) and unlimited smaller art prints and jigsaw puzzle. We will endeavour to recoup the costs of the project (around $250K) and fund our next map which will be of Geelong.

Discuss your relationship with Deborah Young and the first and current Melbourne Map.

Deborah and I spent an extraordinary amount of time together working on the project to complete the first black & white illustration. We both pursued other careers ‘post map’ but kept in contact over the years.

Deborah and Melinda, 1990

When I announced to Deb that I wanted to create a new Melbourne Map we discussed the project over some time, to work out the production challenges and Deborah’s capacity to commit to this huge project given her current life commitments.

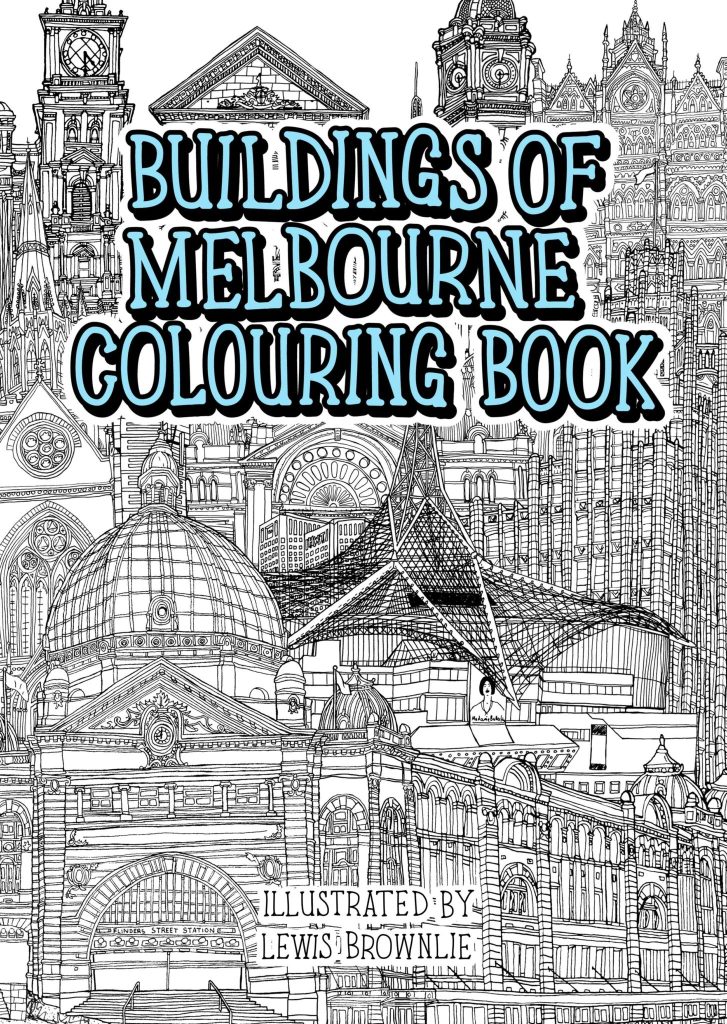

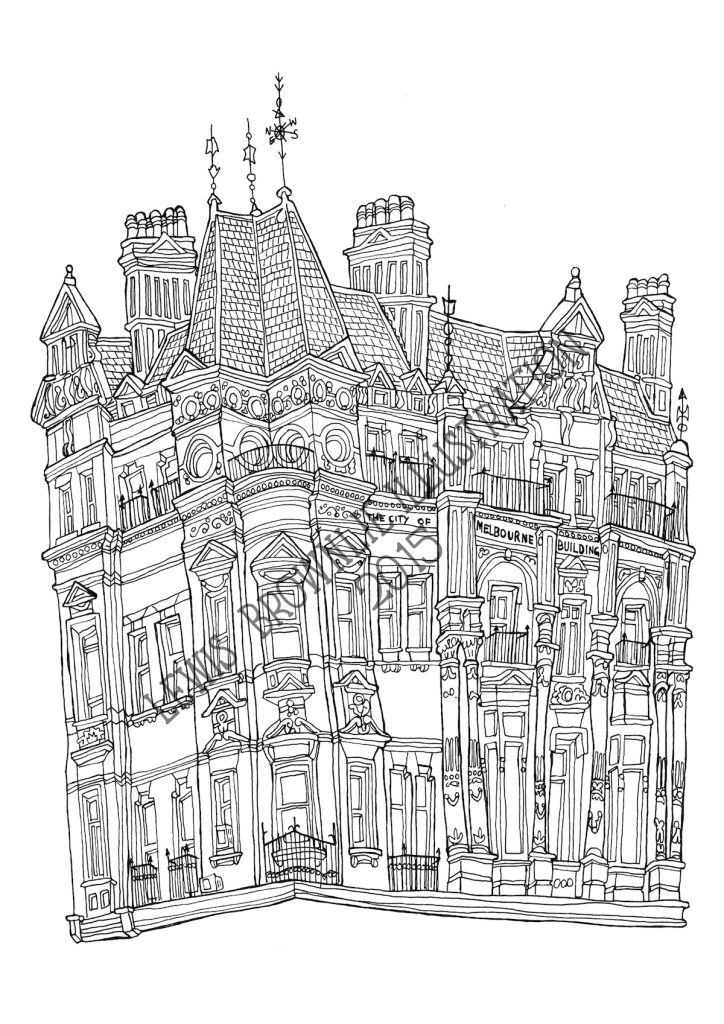

I had also entered into discussions with Lewis Brownlie whom I had met after discovering a Melbourne Buildings colouring book he produced back in 2015.

We all met and worked out the best solution for The Melbourne Map which was for Lewis to take on the role of chief illustrator and draw the lions share of the map including roads, buildings and gardens etc.

How did Lewis Brownlie become involved in the current Melbourne Map project?

I met Lewis after discovering his work in a Colouring book of Melbourne. I contacted him because I thought he might like to see a copy of our first line drawing of Melbourne published back in 1990. As it turned out Lewis lived not far from me and we organised a meeting.