Paula Kovarik

Your most resent exhibition is titled, ‘Stitched Dissent'. Discuss the title and why you feel personally, the need to use art in relations to the current political position of your country?

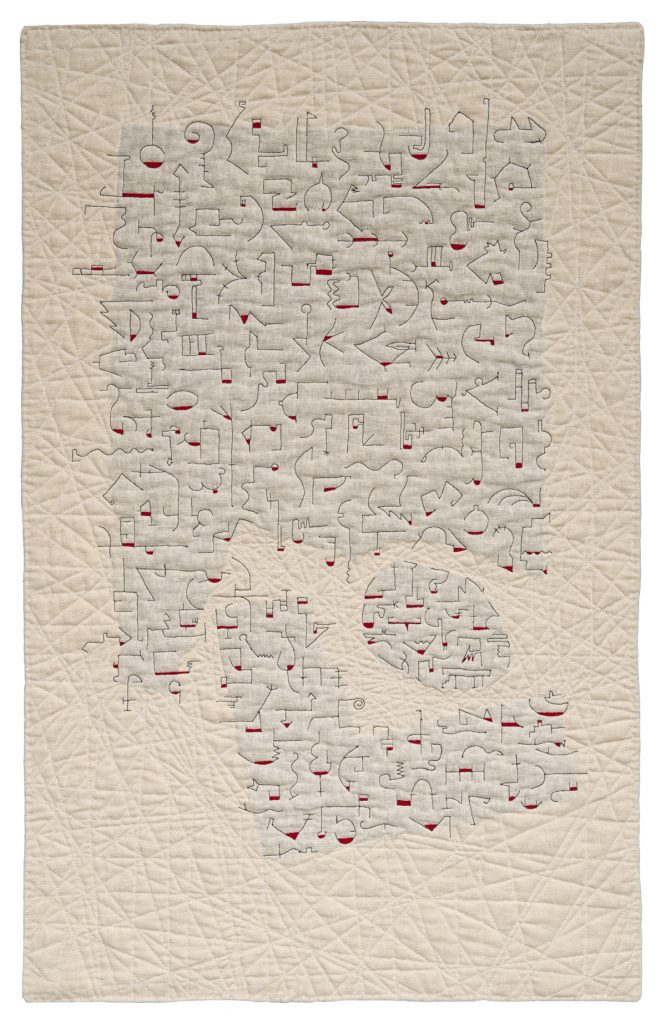

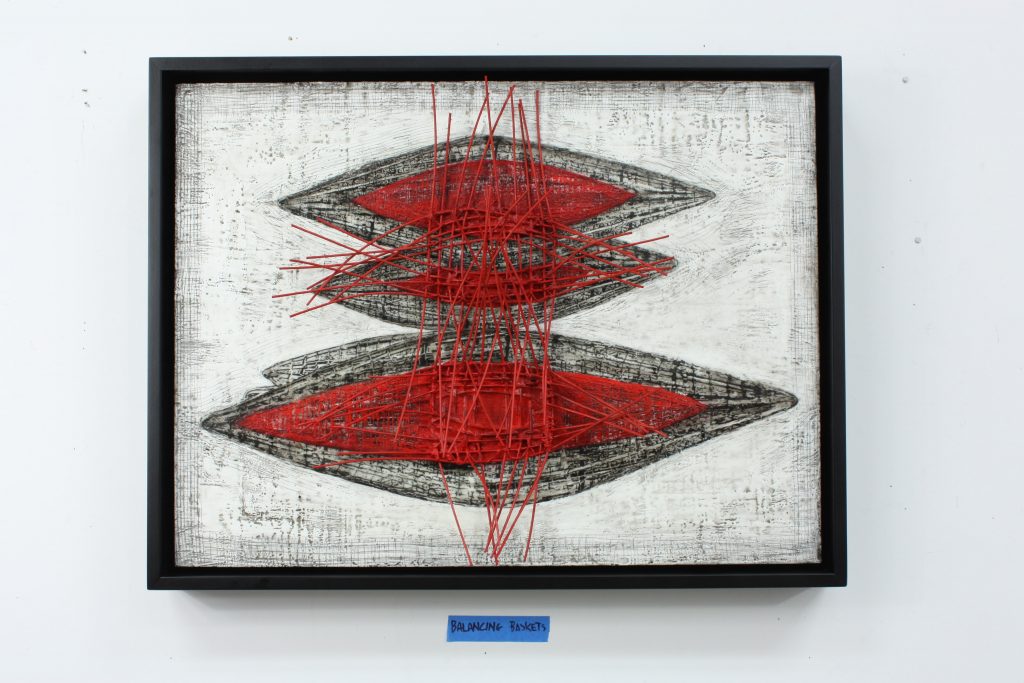

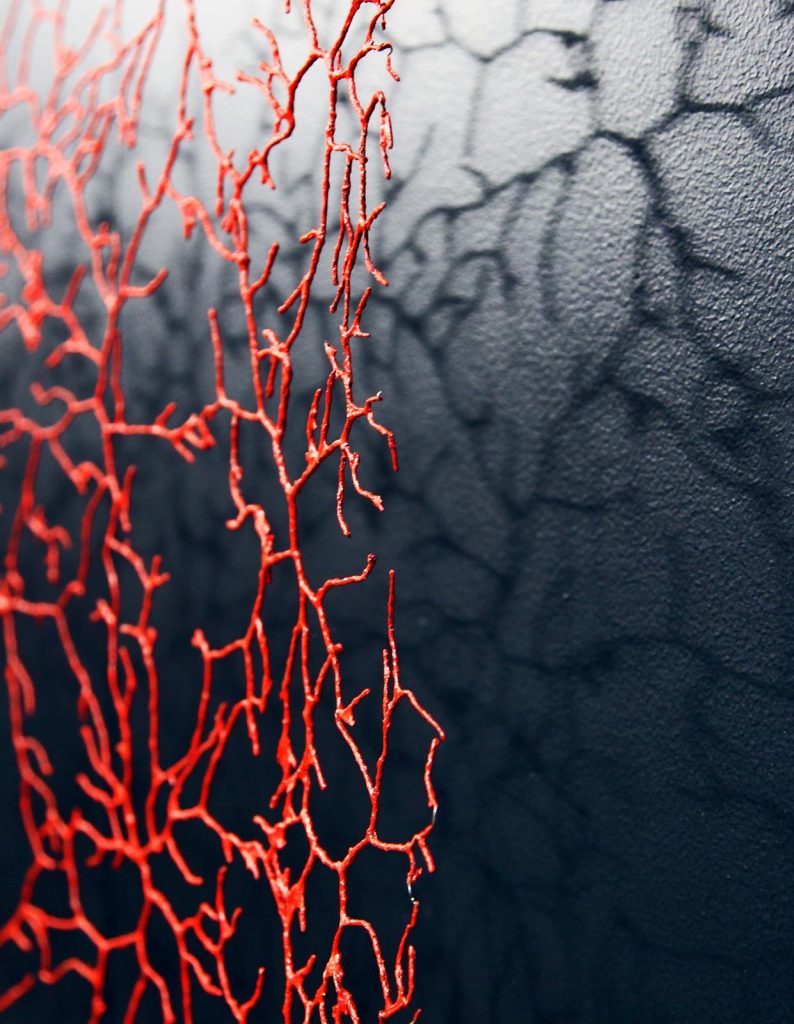

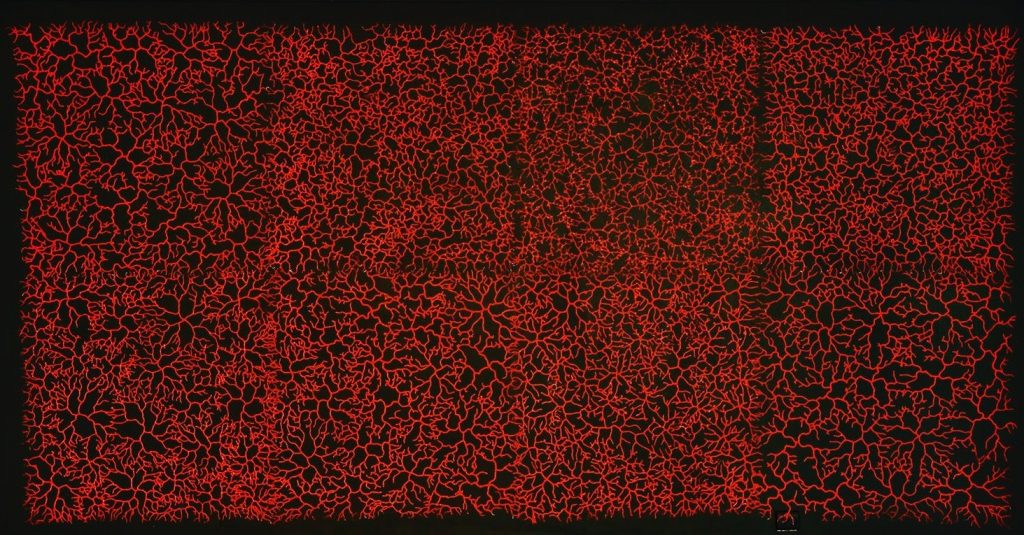

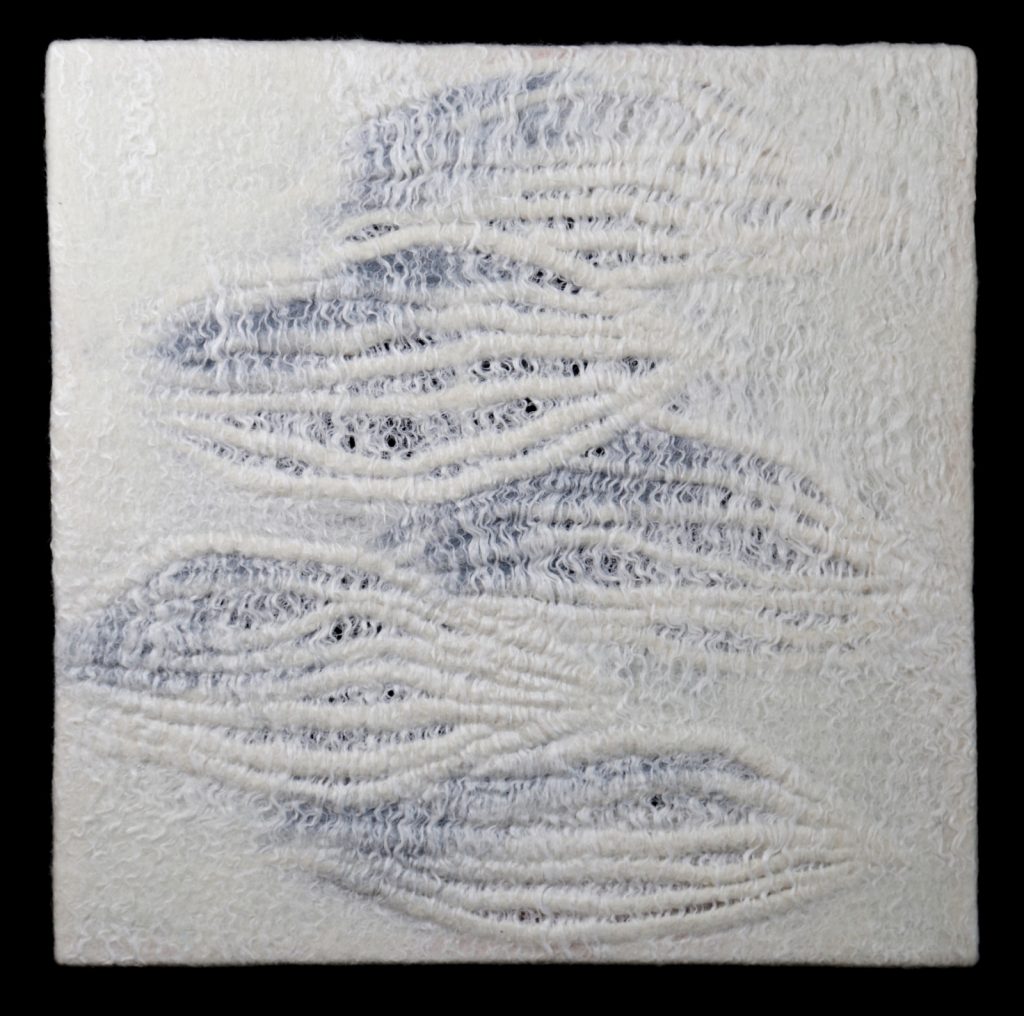

Better Not Said, 41” x 26”, 2019.

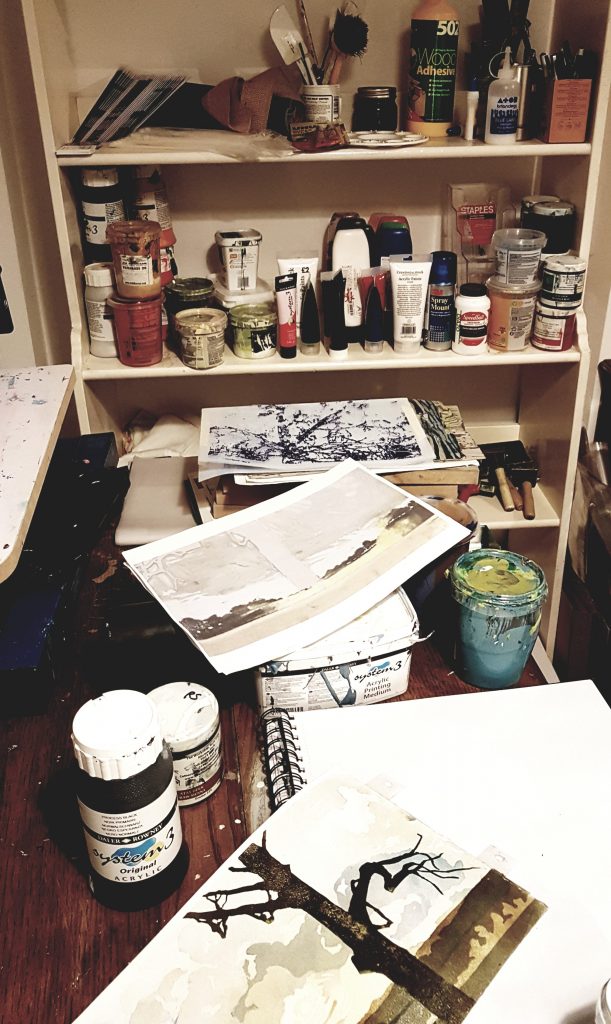

The background

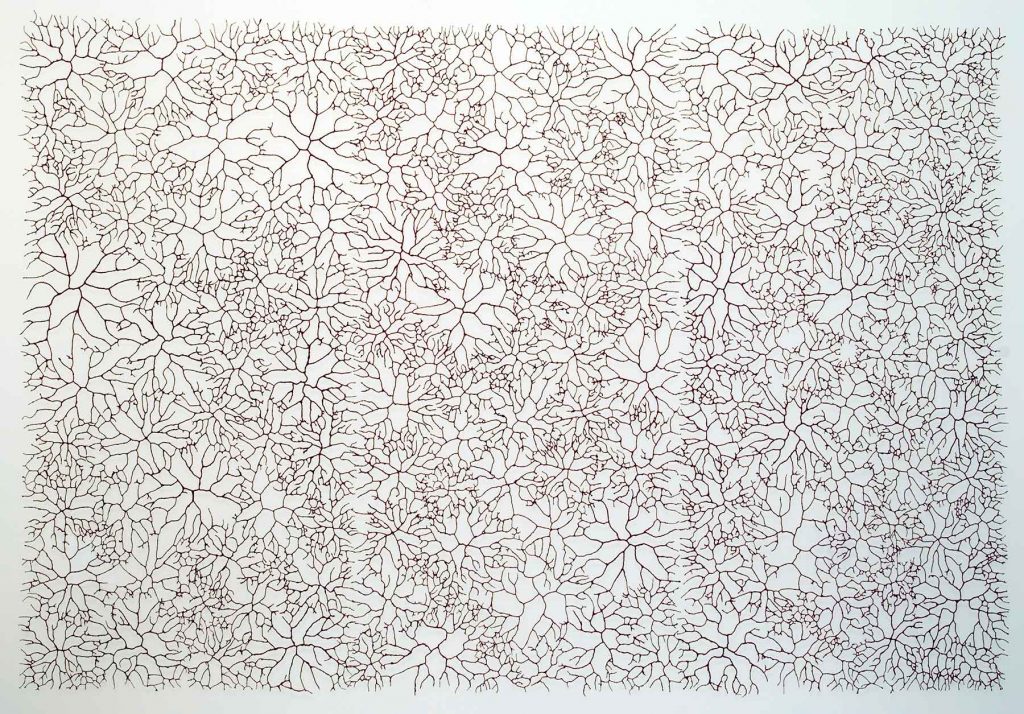

Better not Said began with the idea of how we interpret language with ideograms and lettering.

The use of black, white and red.

I use black thread on neutral backgrounds in much of my work. I find that the high contrast of black against white enhances the mark and speaks loudly about the intent of the mark. After adding all the marks to the piece in black I went back into it to add the red thread.

Symbolism

The red thread that fills in spaces within the black marks represents what we hold back in our conversations. The things NOT SAID.

How has your quilting allowed you to travel the globe?

I teach workshops in many places. But more than that my work travels in shows. That is what is so special about this career. My quilts have been shown across the world.

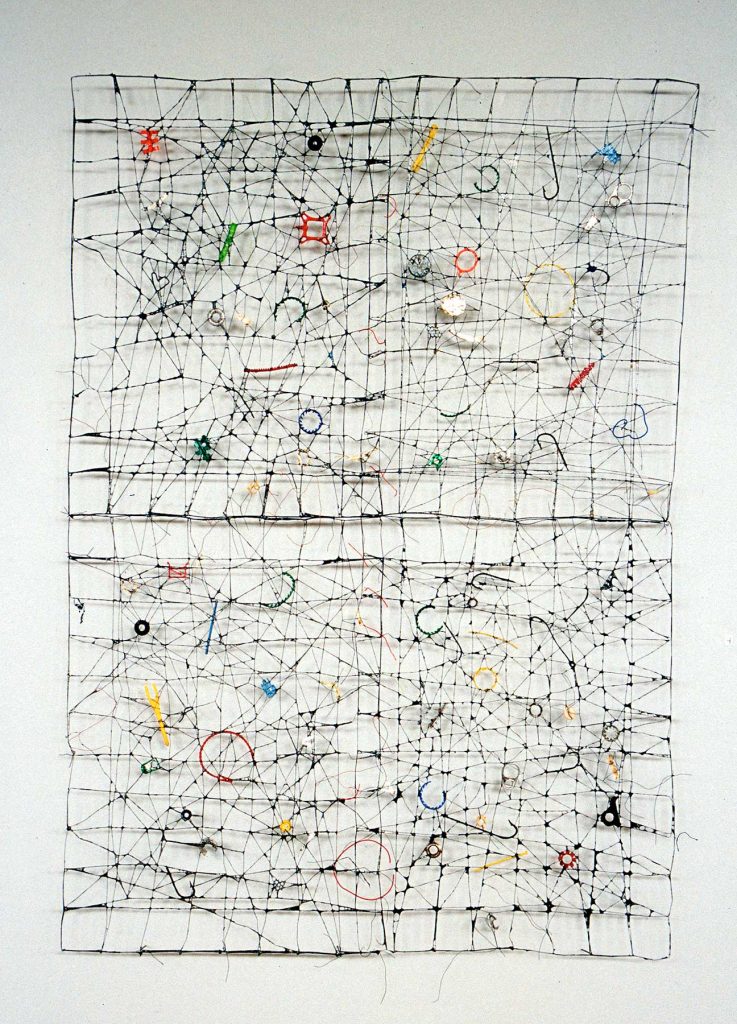

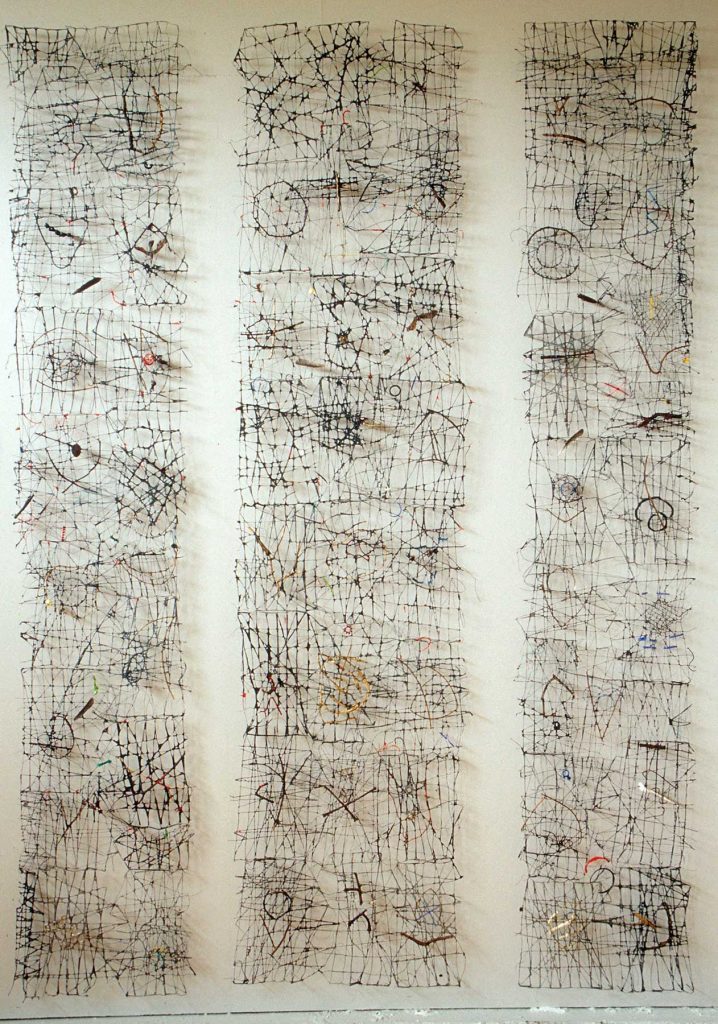

Discuss, line and how you use it in your work.

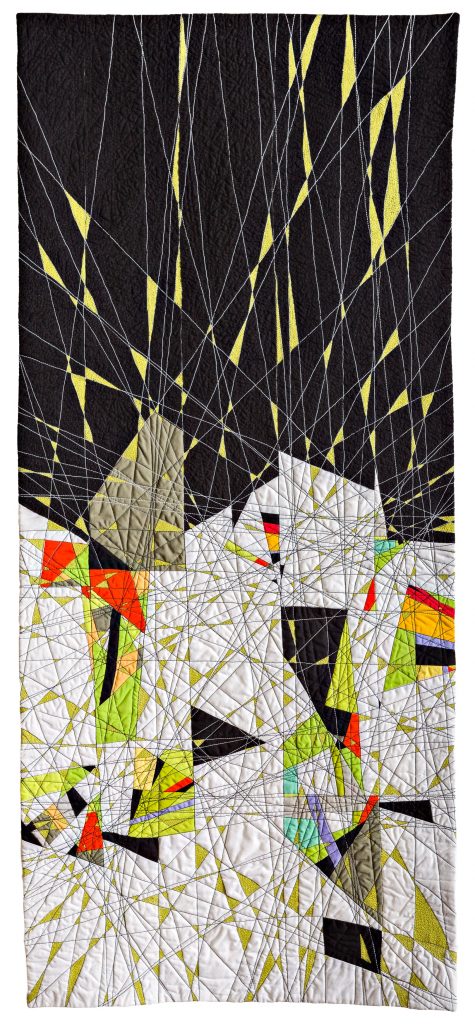

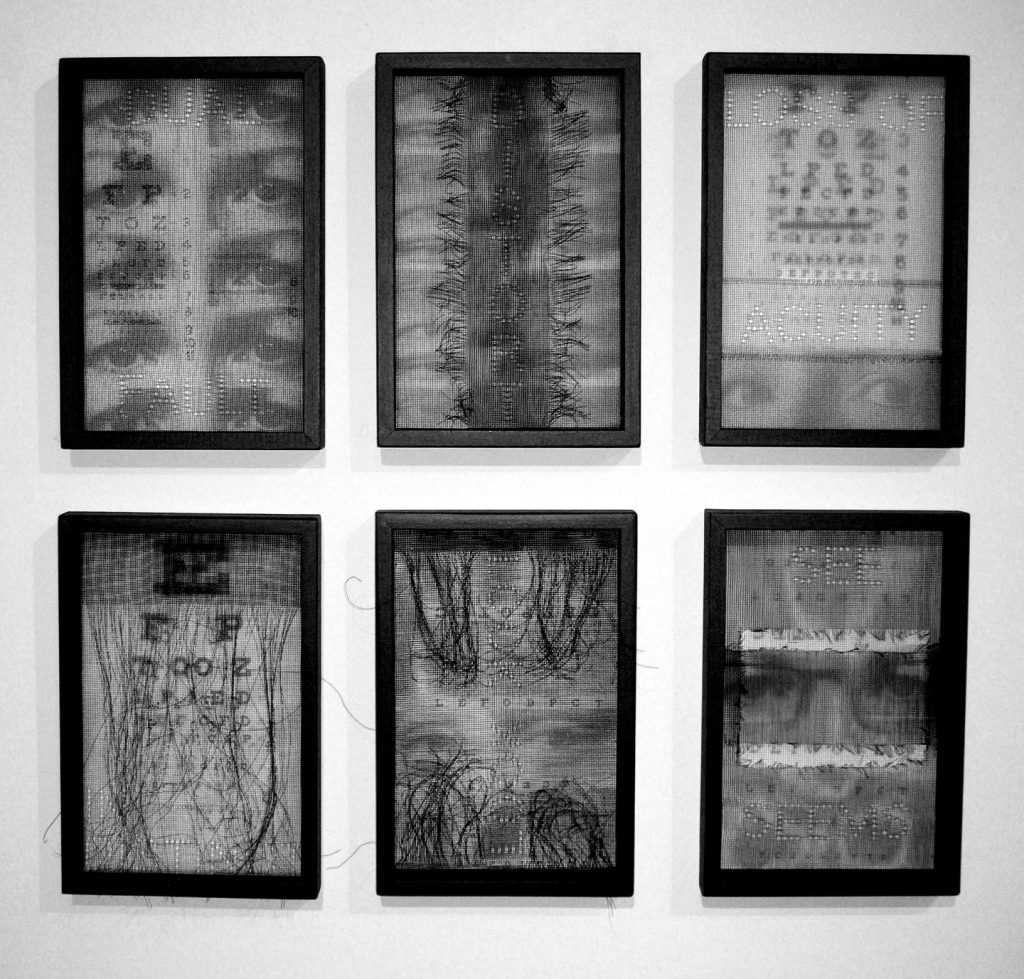

Sightlines, 48 x 19”

Though I do piece fabric and use colour and shape to create compositions my focus has always been on the line created by stitch. It is a language that not only adds texture but also meaning. It controls the density of texture, the direction the eye travels through the piece and the intent of my message.

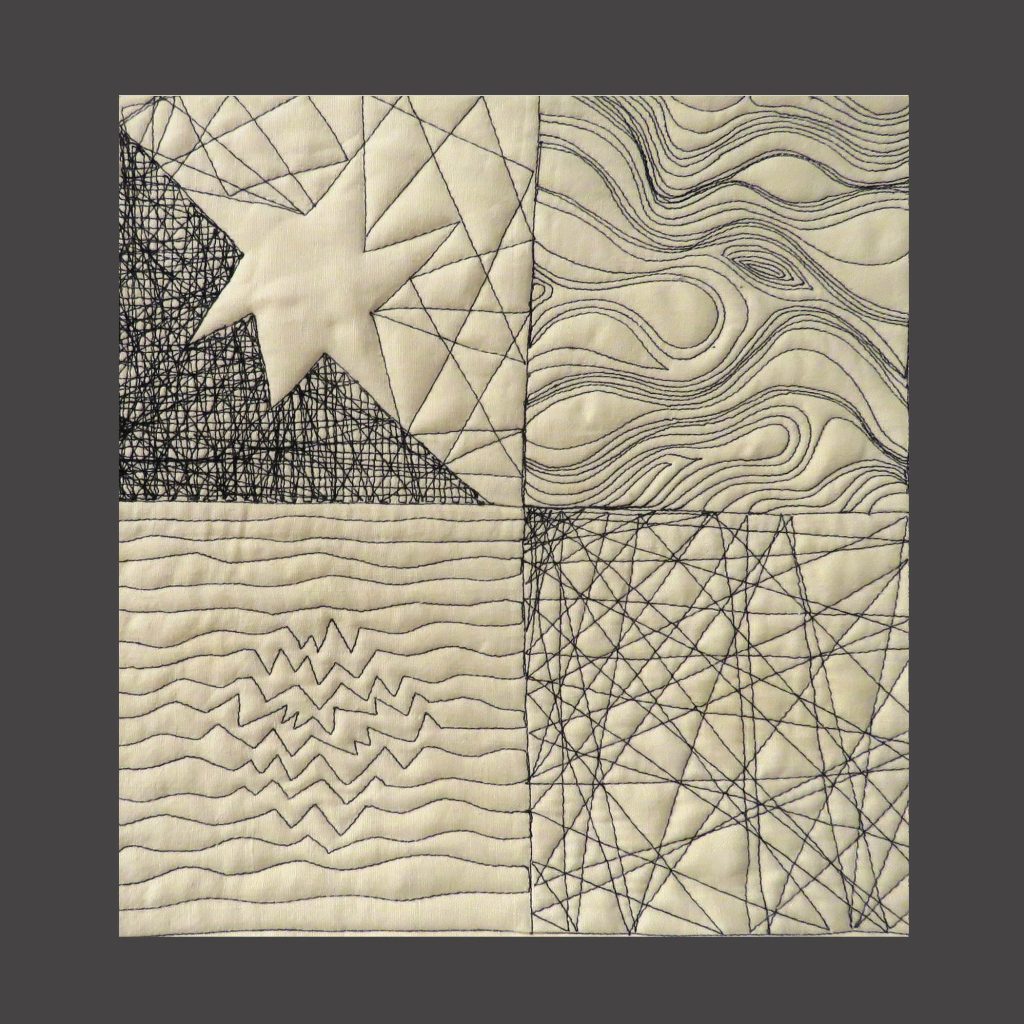

Line Matters, Sample

Line Matters, Sample

How do you want the viewers eye to travel around your quilts?

With wild abandon.

Pathways, 27.5 x 28.25”

Briefly take us through the quilting journey you have taken over your artistic career.

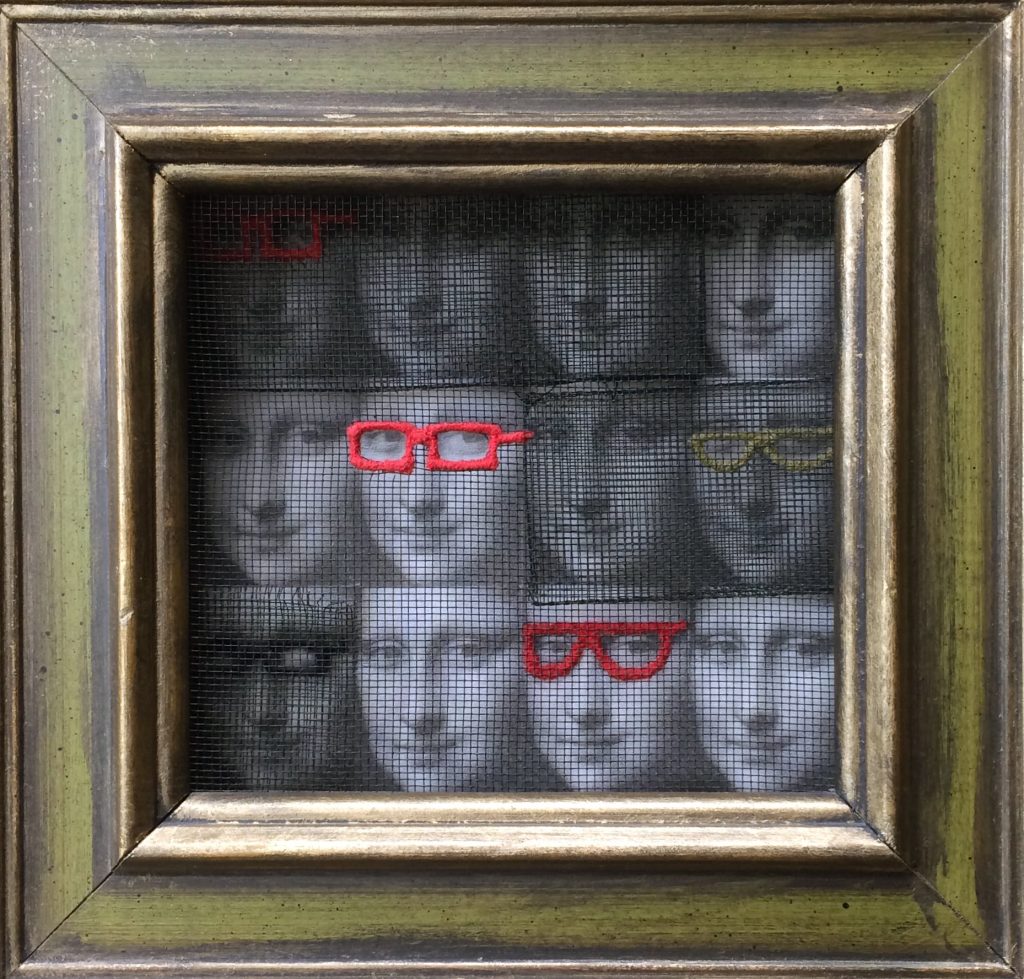

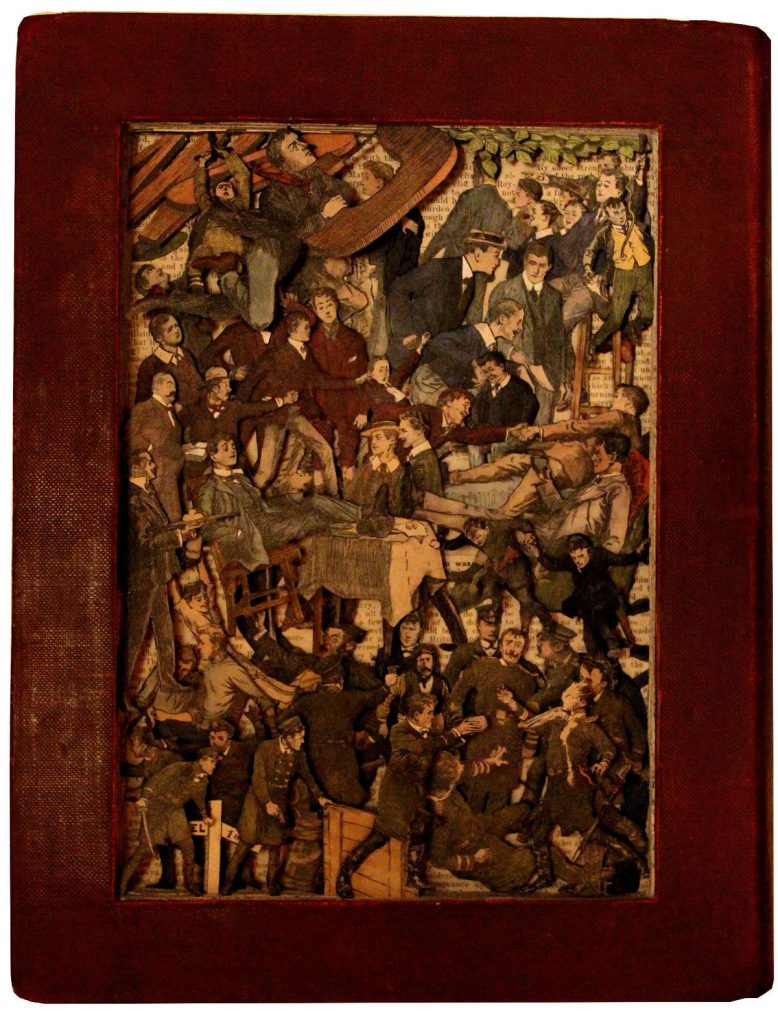

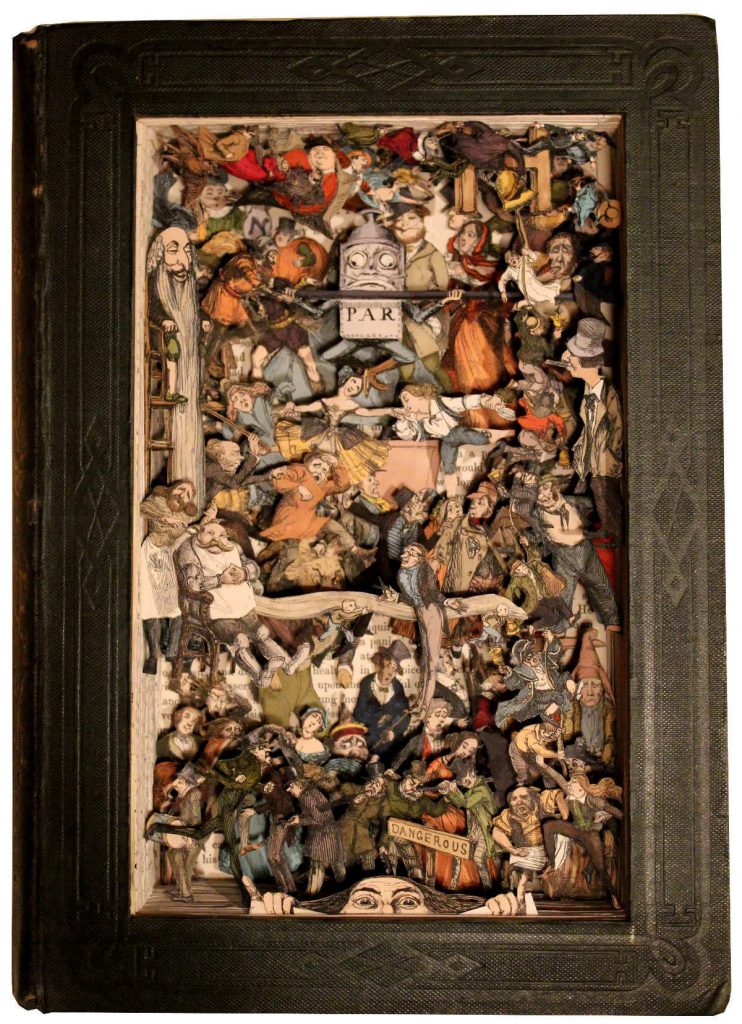

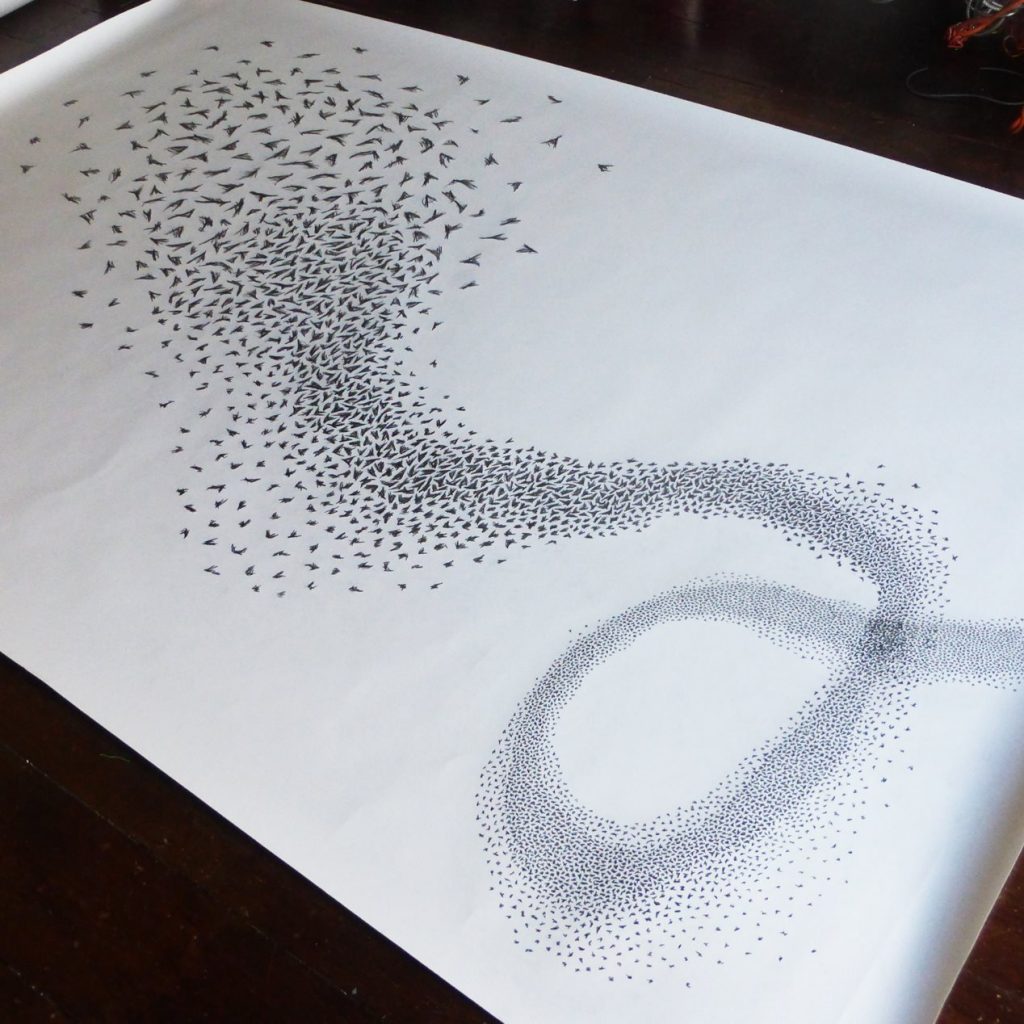

Dissemination, a small piece about crowds and leaders. 12” x 14”, 2006

Dissemination, a small piece about crowds and leaders. 12” x 14”, 2006

I started quilting after my mother introduced me to the craft about 15 years ago. Though I am not a traditional quilter I found that working with fabric and thread was a natural medium for me. I loved the textural quality of it. I am a graphic designer by trade and creating messages through composition and imagery comes naturally to me. I began to apply my design skills to this new medium in order to find my own unique approach to this art form.

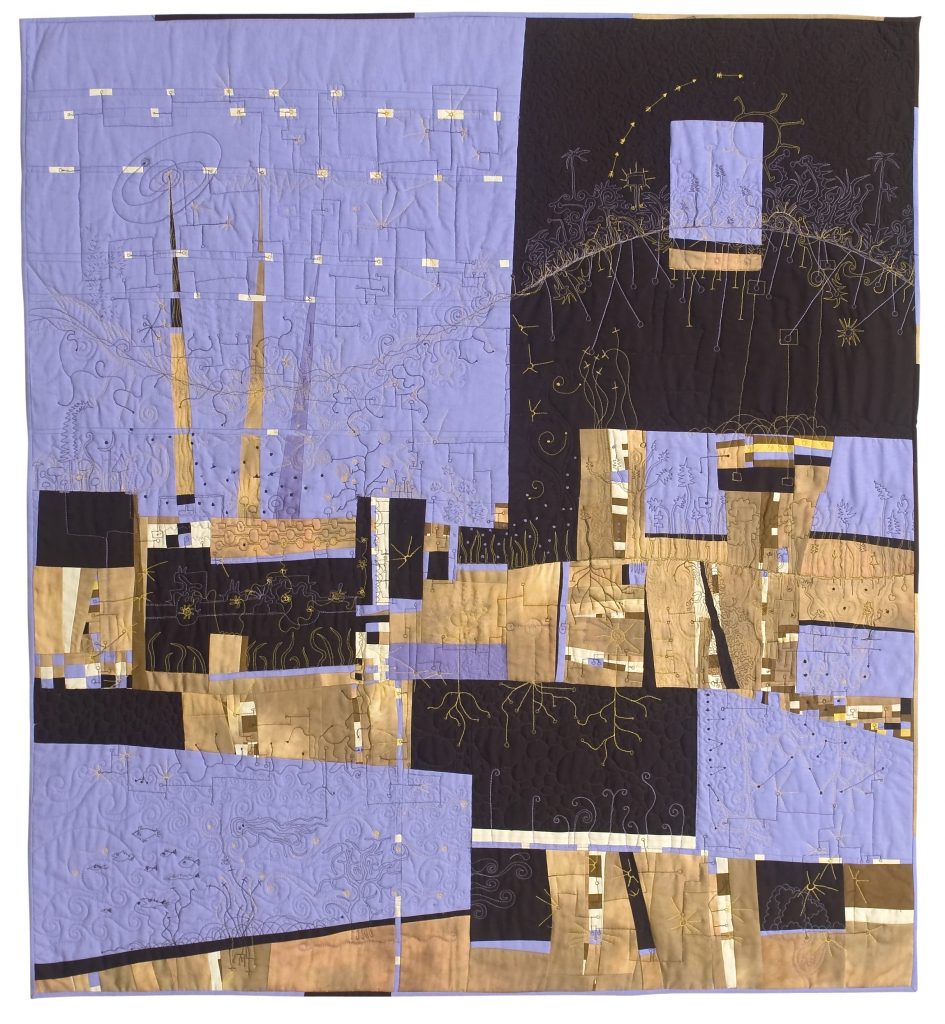

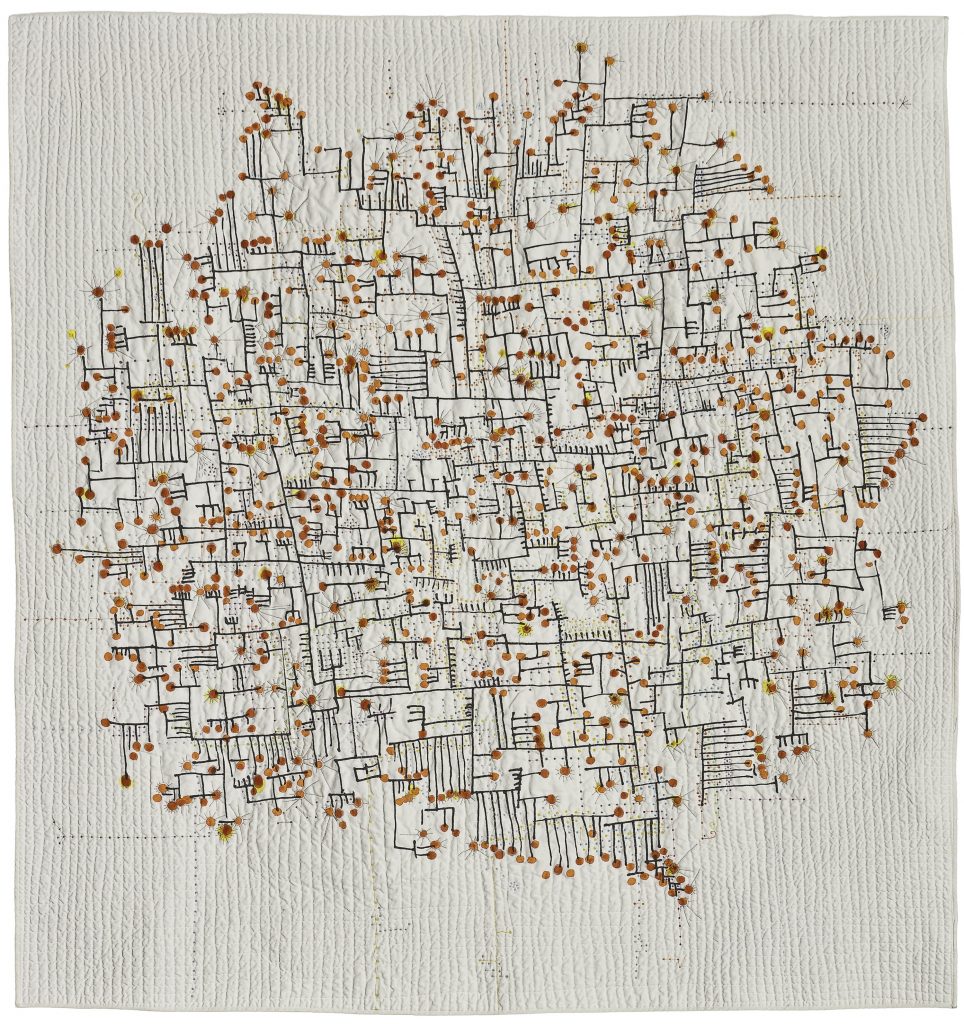

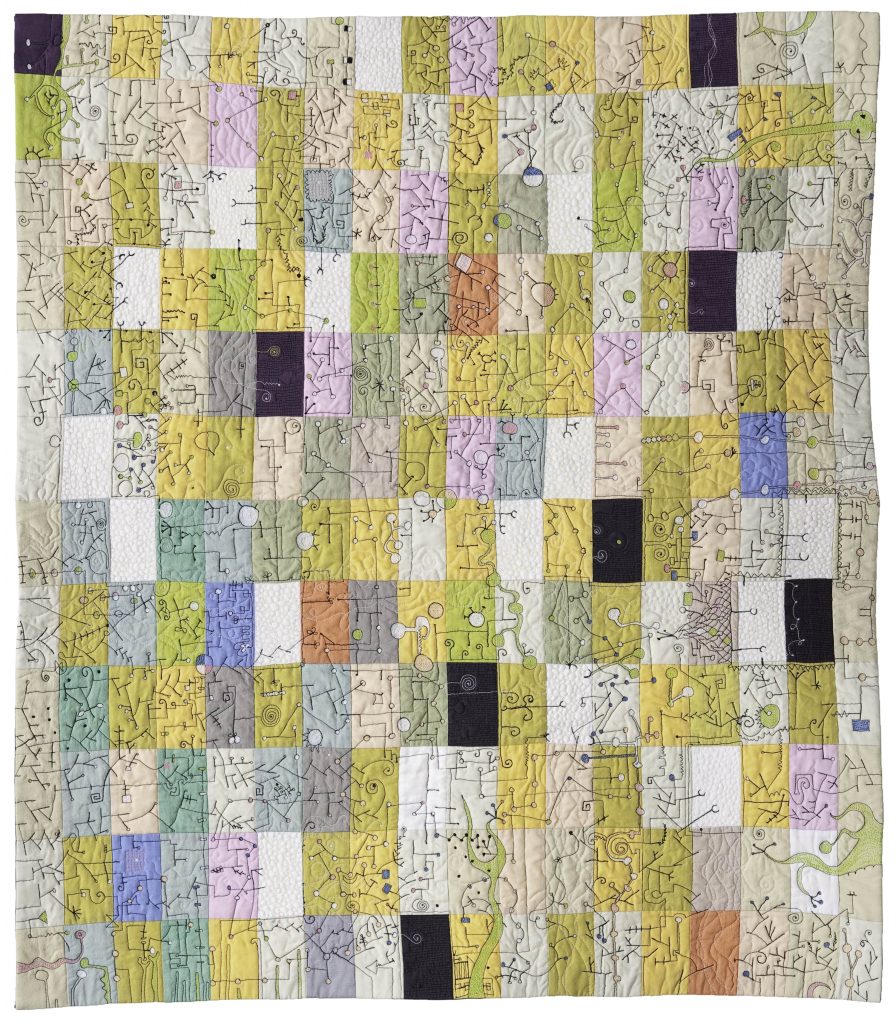

City, 41.5” x 38”. 2008.

City, 41.5” x 38”. 2008.

City, one of the first pieces I made that was accepted into Quilt National.

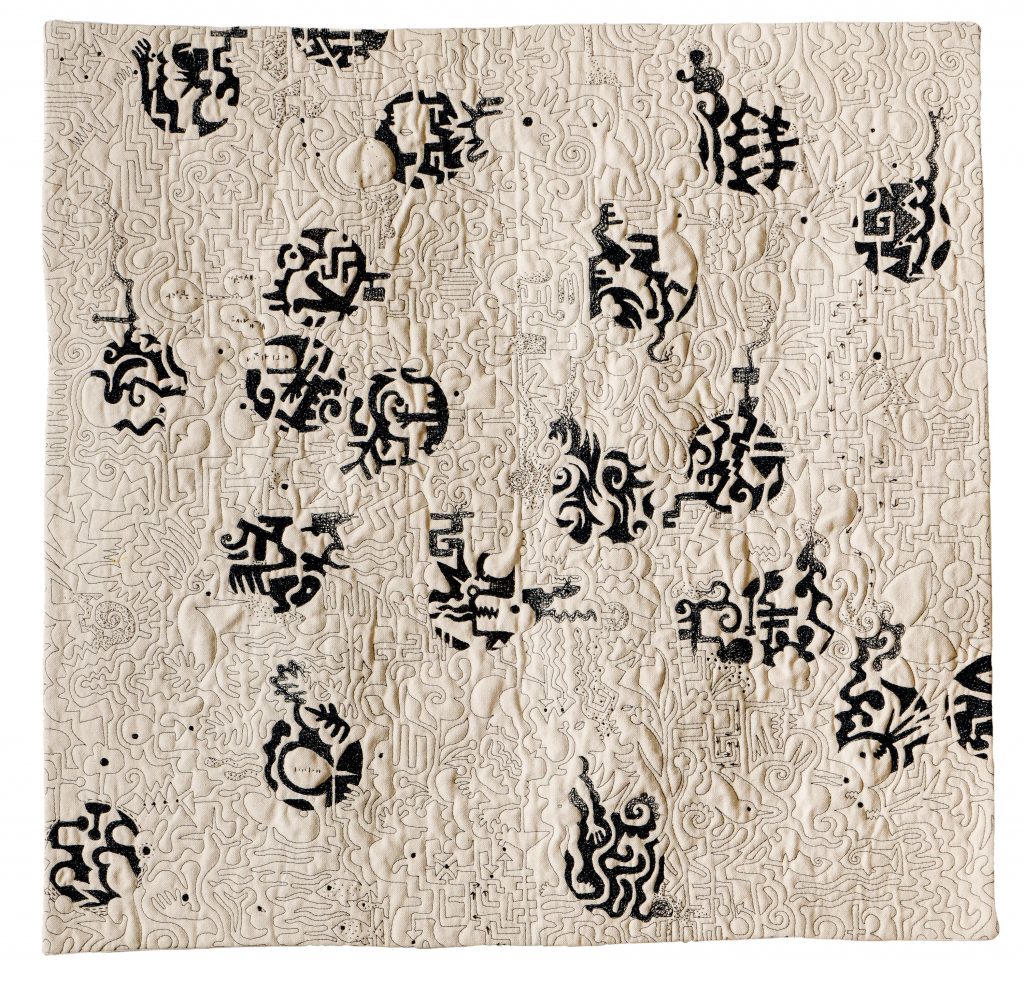

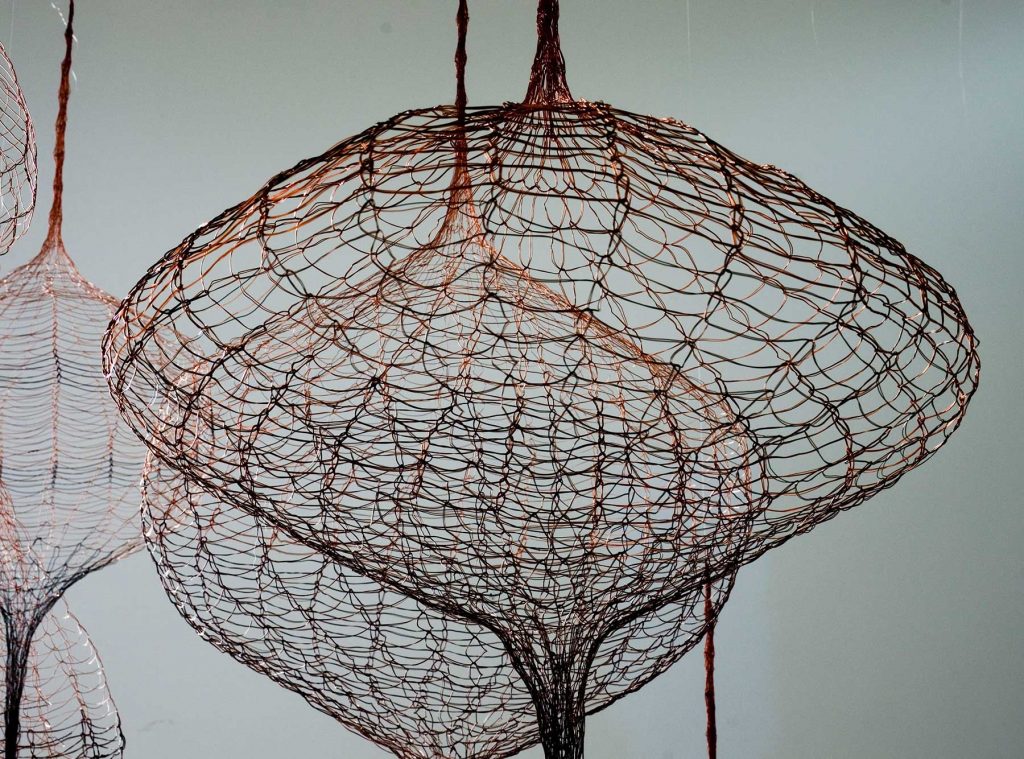

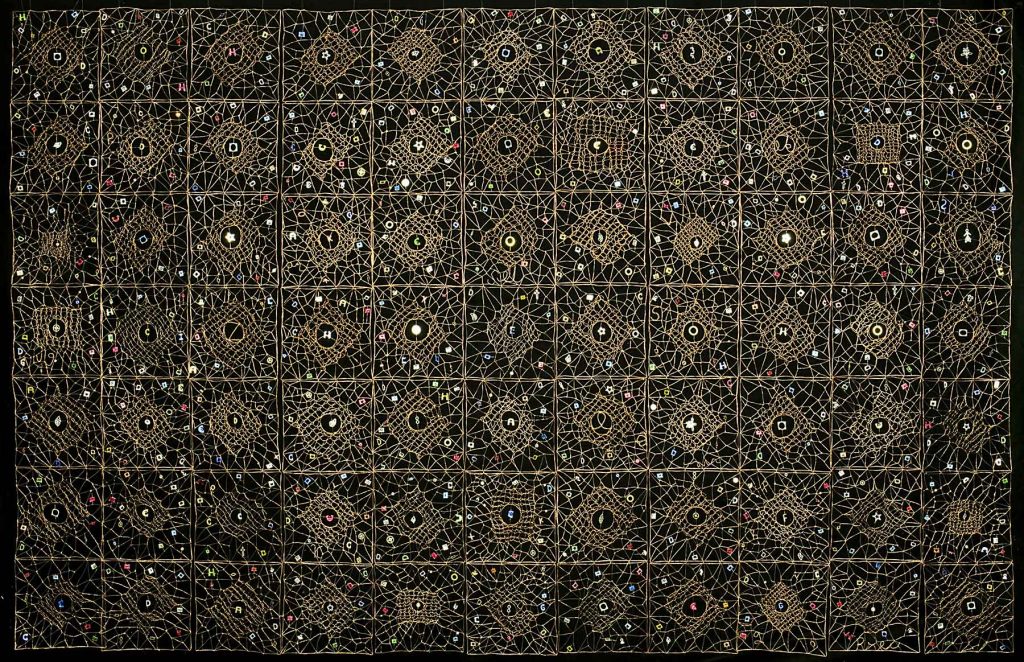

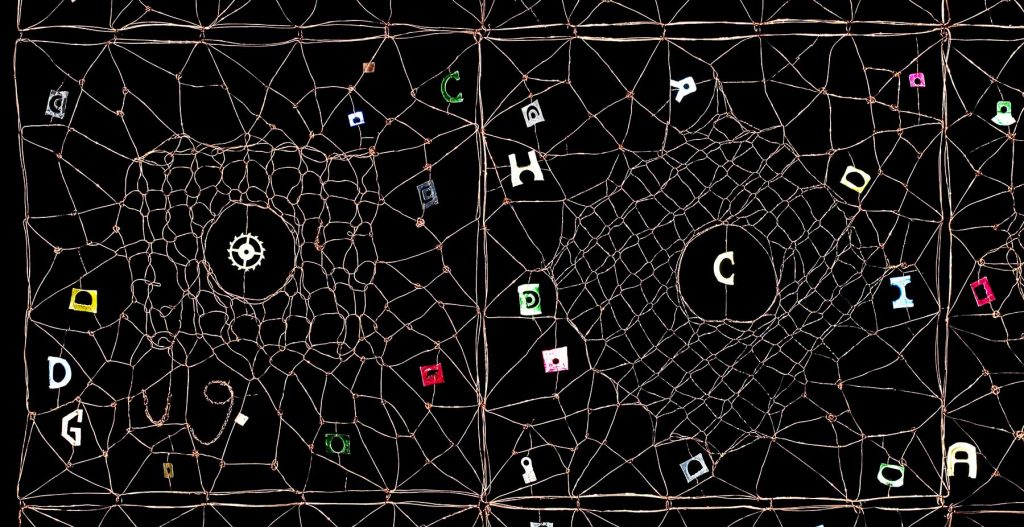

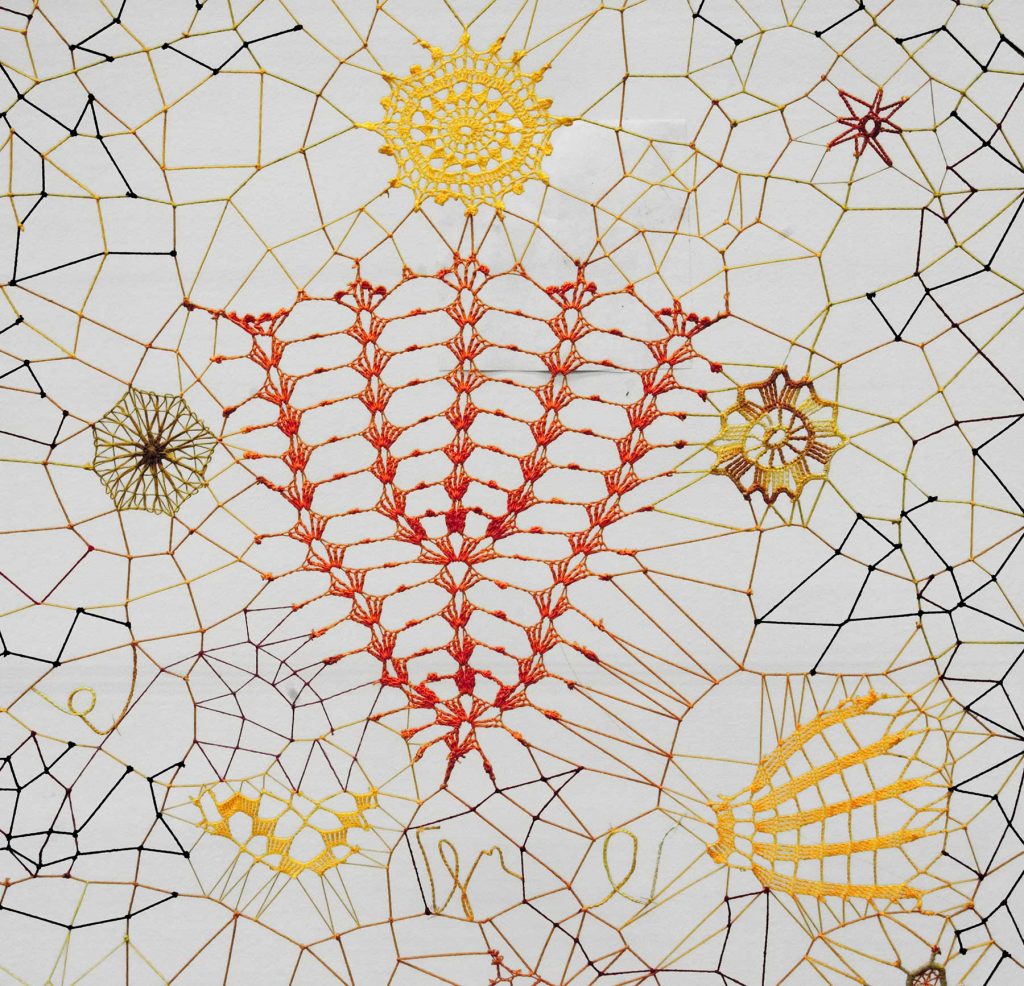

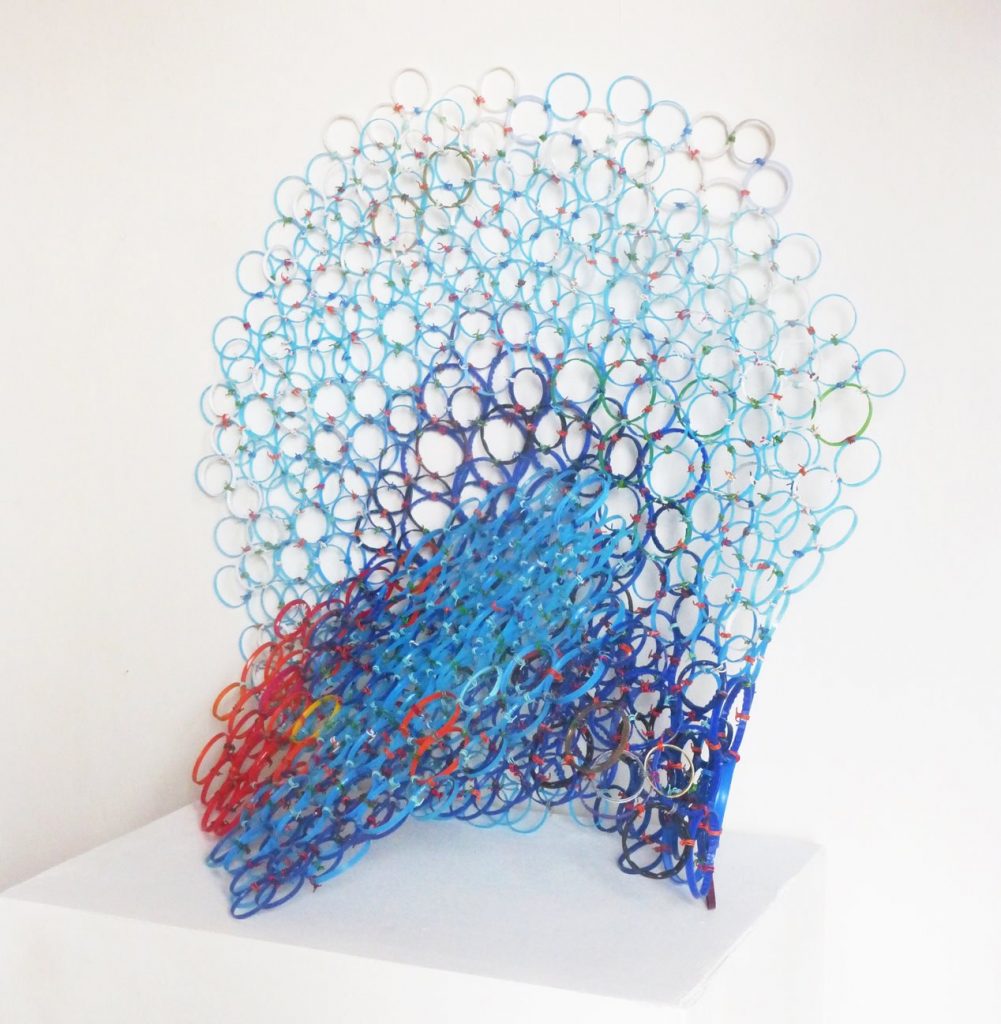

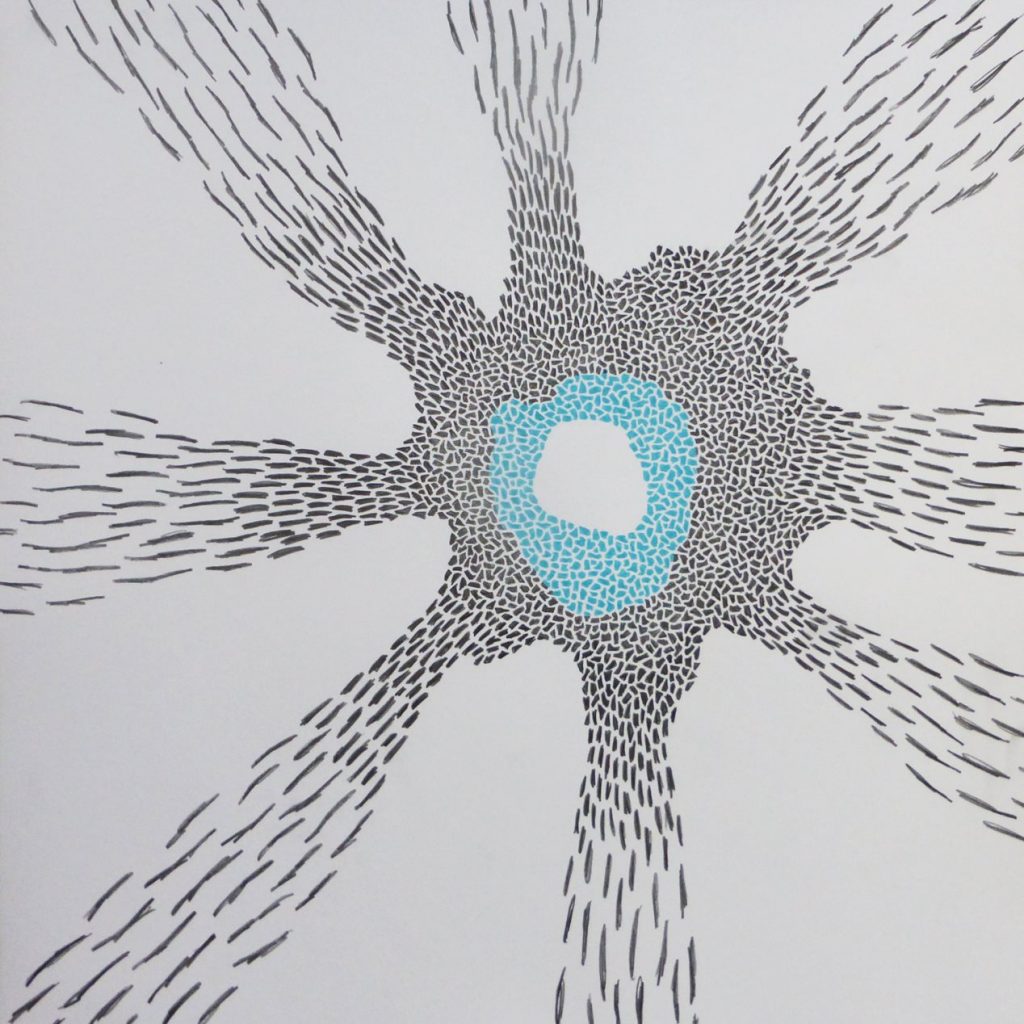

AHA! Moments, a piece that started with a doodle drawing that was enlarged and stitched over. It’s all about how our brain connects points of data.

AHA! Moments, 57” x 54” 2010.

AHA! Moments, 57” x 54” 2010.

Round and Round It Goes, a piece that focuses on all the threats in the world from roaches to terrorists.

Round and Round It Goes, 54” diameter. 2013

Round and Round It Goes, 54” diameter. 2013

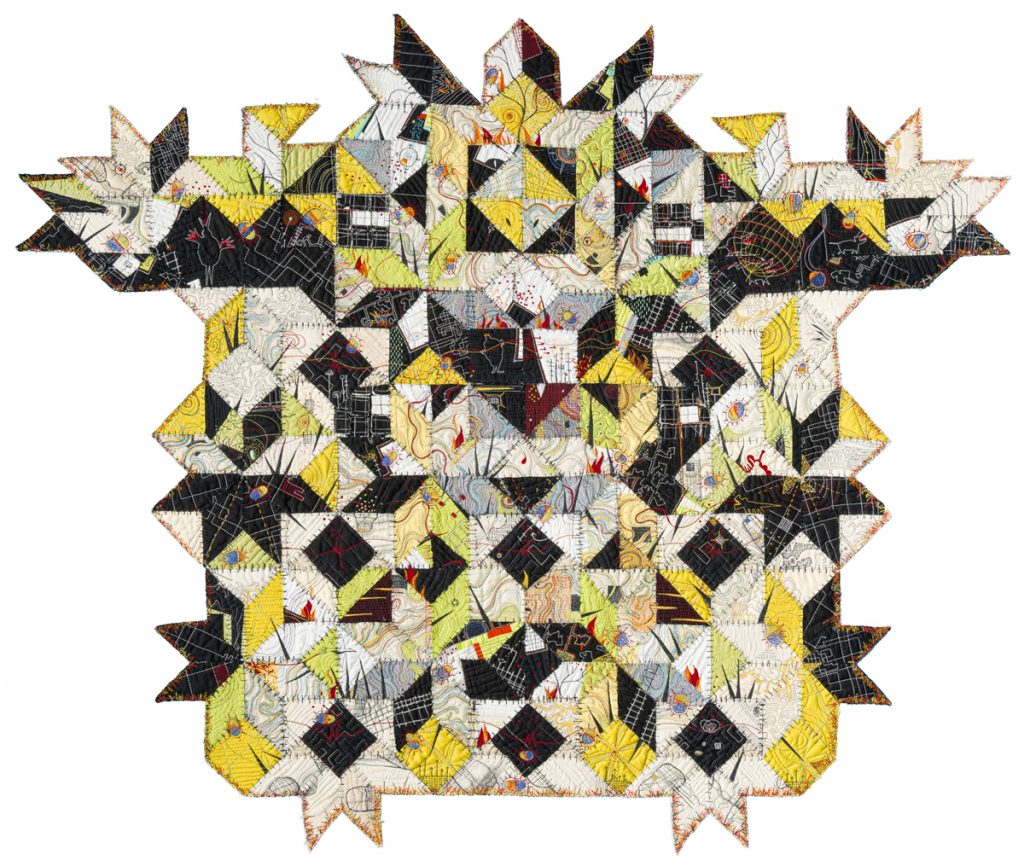

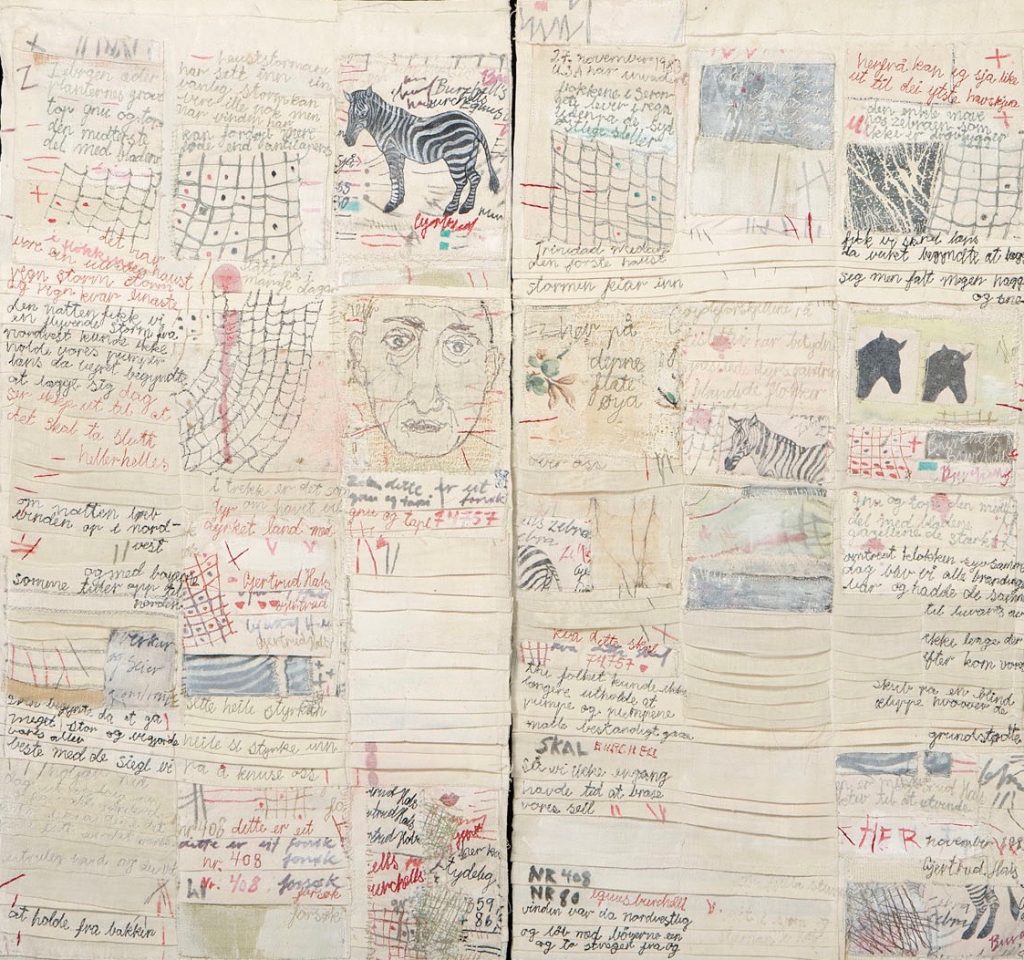

Chaos Ensues, a collage piece that brings diverse pieces of fabric together to tell a story of chaos. 32” x 32”, 2017

Chaos Ensues, 32” x 32”, 2017

Chaos Ensues, 32” x 32”, 2017

My current work.

Dark Heart, 46” x 55”. 2019.

Dark Heart, 46” x 55”. 2019.

Dark Heart, A piece that assembles pieces from other quilts to create a new being.

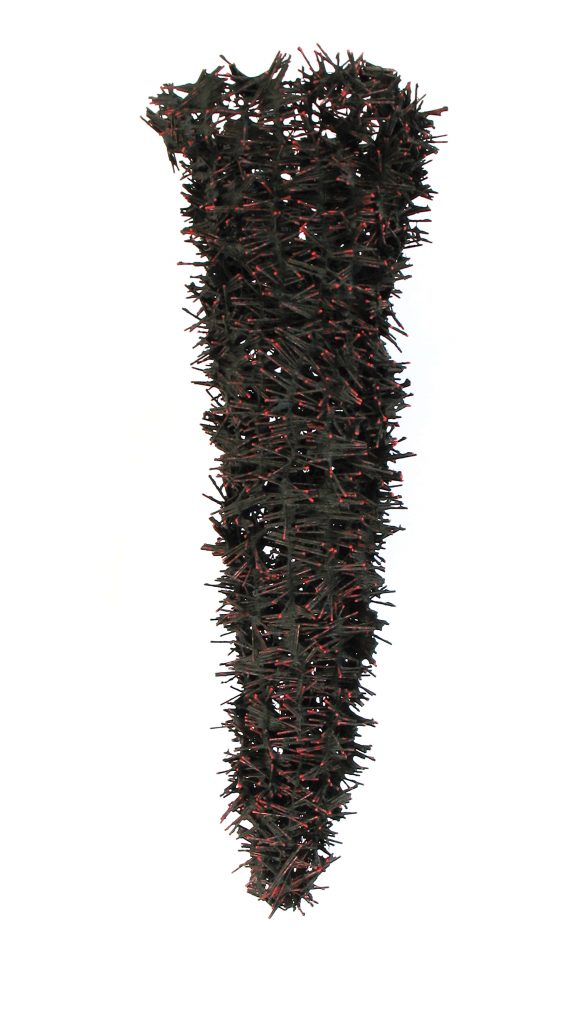

Comment on the way you use raw edges in your work.

I find that the more I work in this medium the messier I am getting. I love the raw quality of edges with threads hanging. Layered stitching adds depth and dimension. Piling on layers adds a textural element that is difficult to show in other 2D mediums.

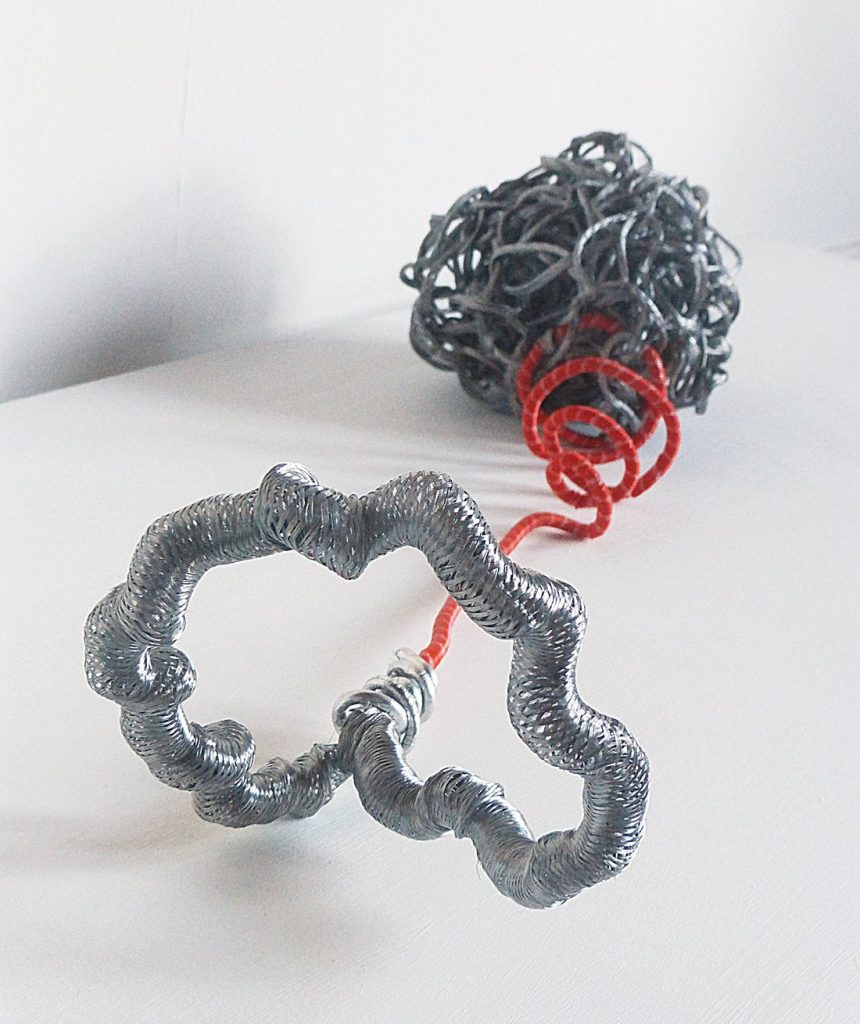

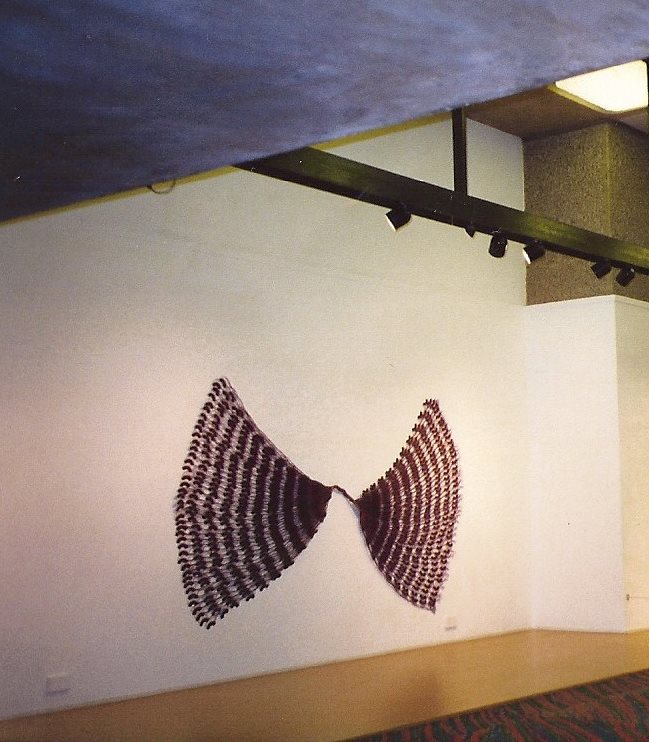

Discuss the work ‘Insomnia'.

Insomnia was inspired by the world-wide economic collapse we all experienced in 2008. My business had suffered the loss of clients, I was worried about our savings and retirement and life was just a barrel of anxiety. All those thoughts went into these two pillow forms.

Size – How do you decide on the size of each quilt?

The quilts themselves determine their size. I build from bits and they grow to their mature size.

Backing – The backing of a quilt is an important part of each quilt. Comment on your thoughts on this aspect of quilting artistically.

I have many quilts that are two-sided because of the way the backing shows a different version of the stitching on the front. Since my stitching is so idiosyncratic, I often find new thoughts when I turn the quilt to the back.

Your mother passed on many craft skills to you. How do you see education filling these gaps currently.

I study art daily. I seek out artist talks, exhibits and critiques. But education also fills in another very important aspect of my practice. I read voraciously: science, politics, novels, poetry, botany, history, and commentary. These readings add bulk to my understanding of the world and find harbor in my work.

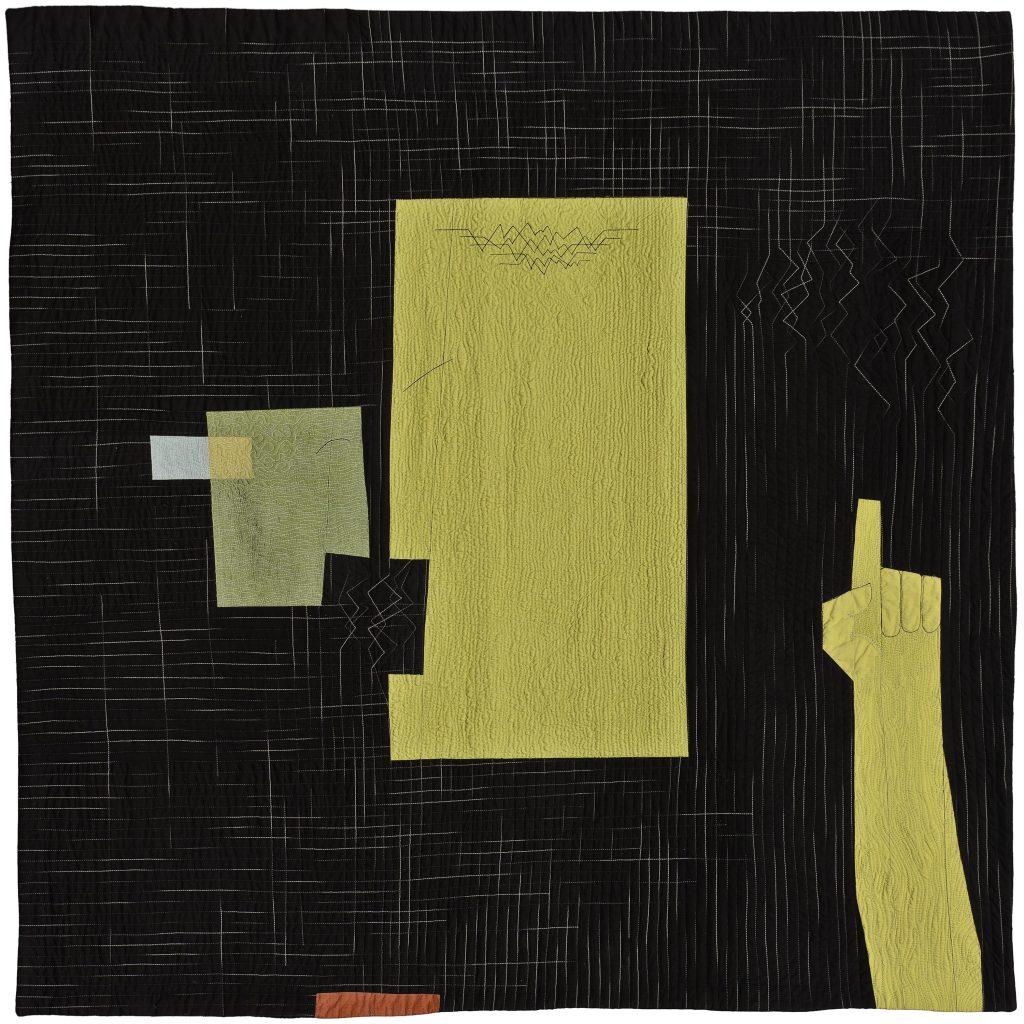

Pundit, 41.5 x 41.5”

Pundit, 41.5 x 41.5”

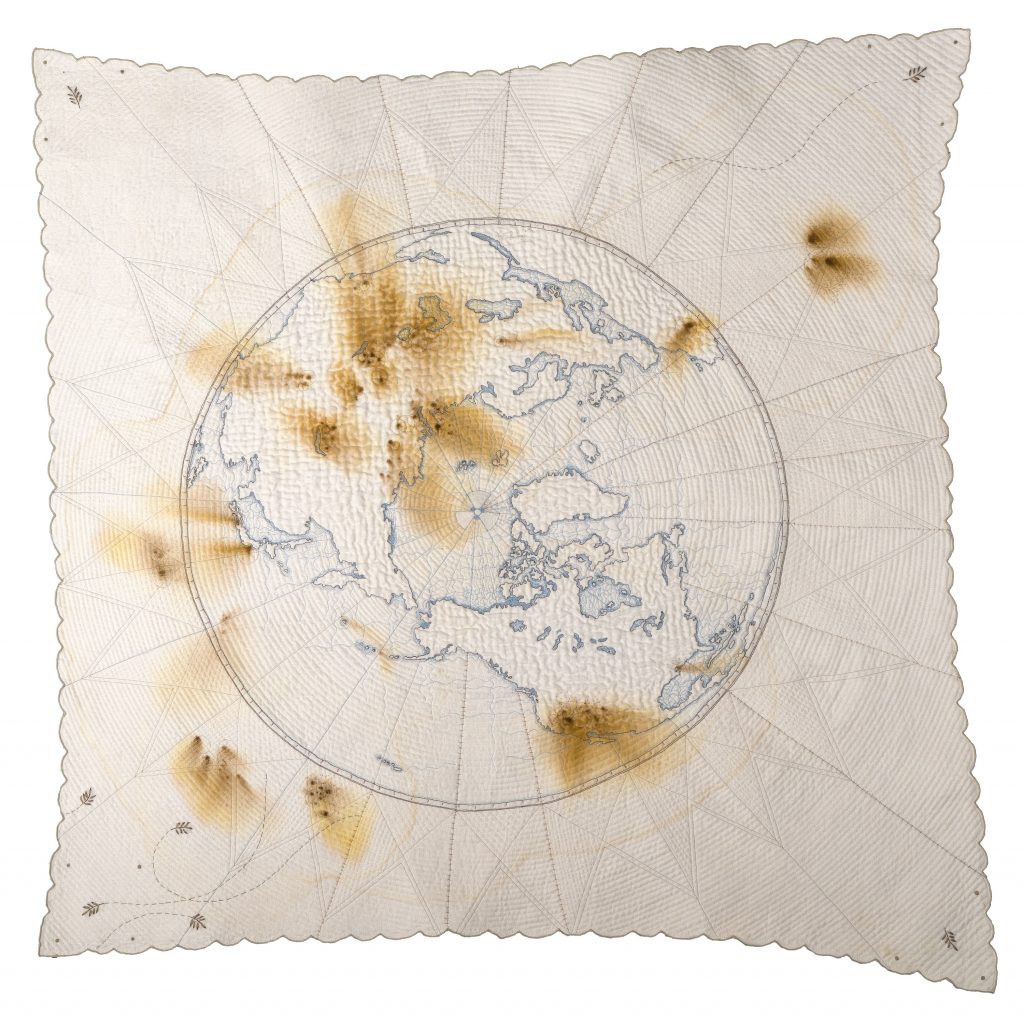

Take ‘Fallout’ and discuss the use of stains in this work.

Fallout is about nuclear testing. I wanted the work to look like an antique map. I used a vintage tablecloth as my substrate. I stitched the continents and oceans with blue and brown threads. Hand stitching added texture to the continents. Then I used tea to stain the piece to add depth. The dark brown spots made with dye represent areas on the earth where nuclear testing has been executed.

Fallout, 41.5” x 41.5” , 2017

Titles of works always have deep meanings can you take three quilts and discuss their title and why?

Connecting Fantasy to Reality Proved Difficult 39” x 34”, 2010

Connecting Fantasy to Reality Proved Difficult 39” x 34”, 2010

This is an early piece that was traditionally pieced but then stitched in a fantastical way. The contrast is striking.

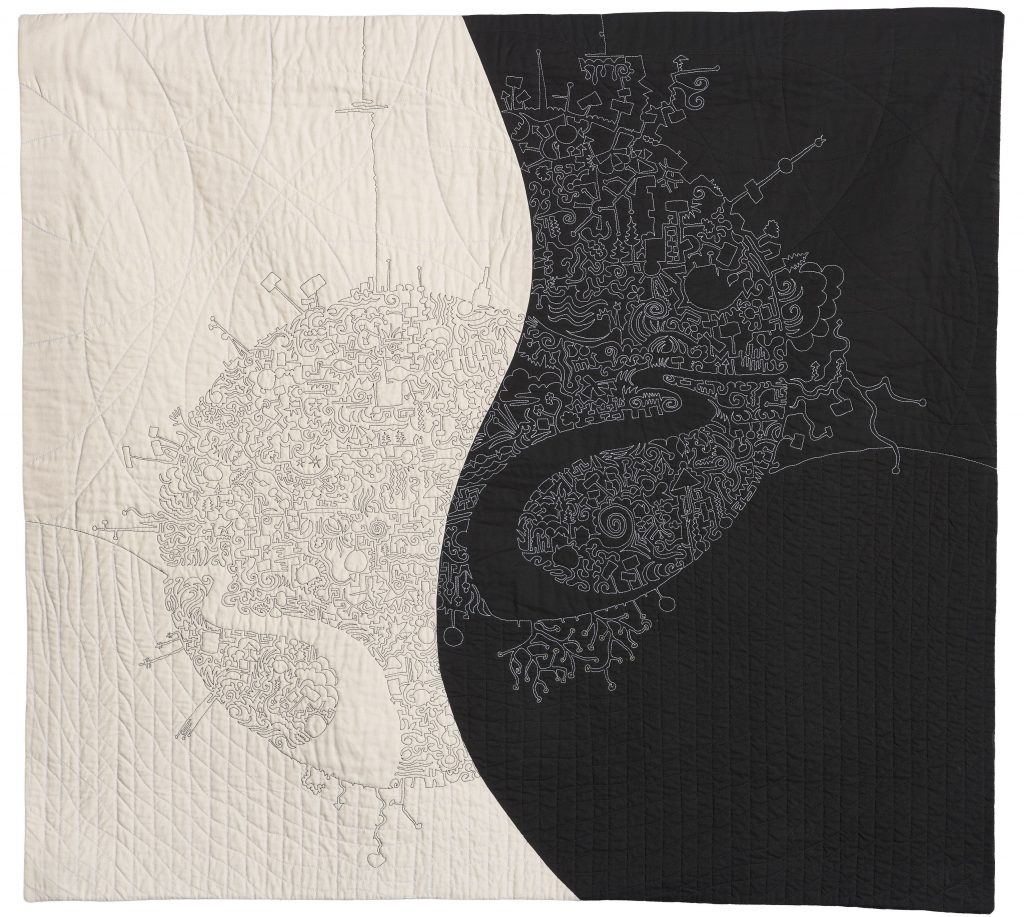

Same But Not: This piece shows the trajectory and journey of two threads, one black and one white. It is a dialog about race and separation. 39.5”x 42”, 2011

Same But Not, 39.5”x 42”, 2011

Same But Not, 39.5”x 42”, 2011

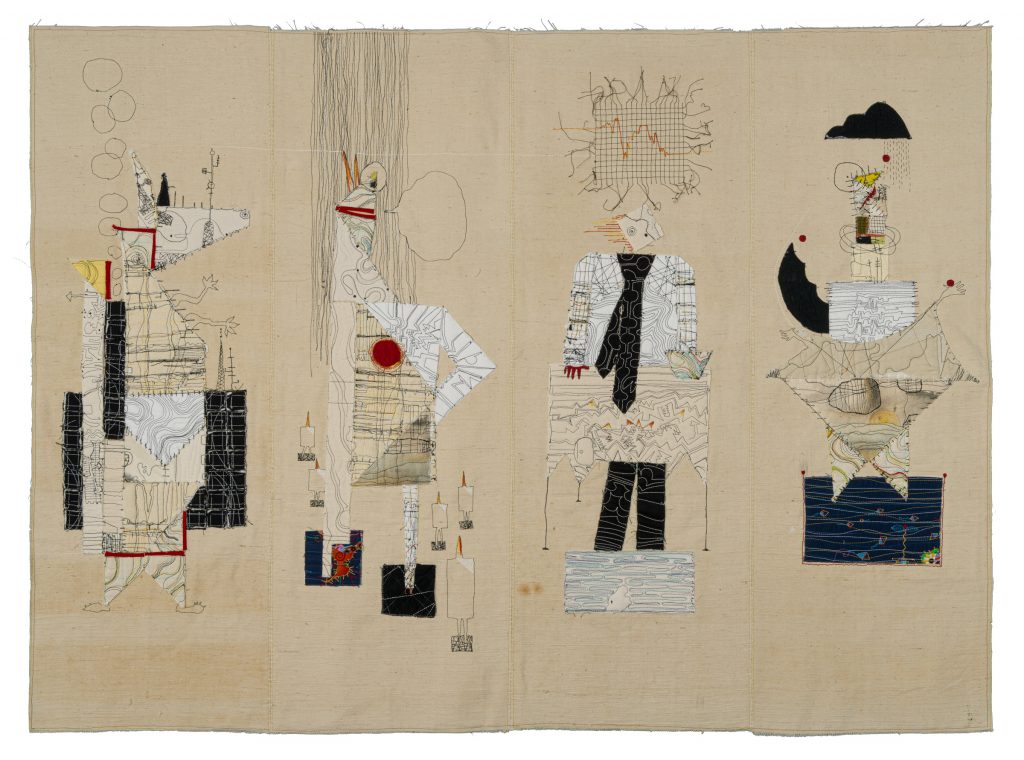

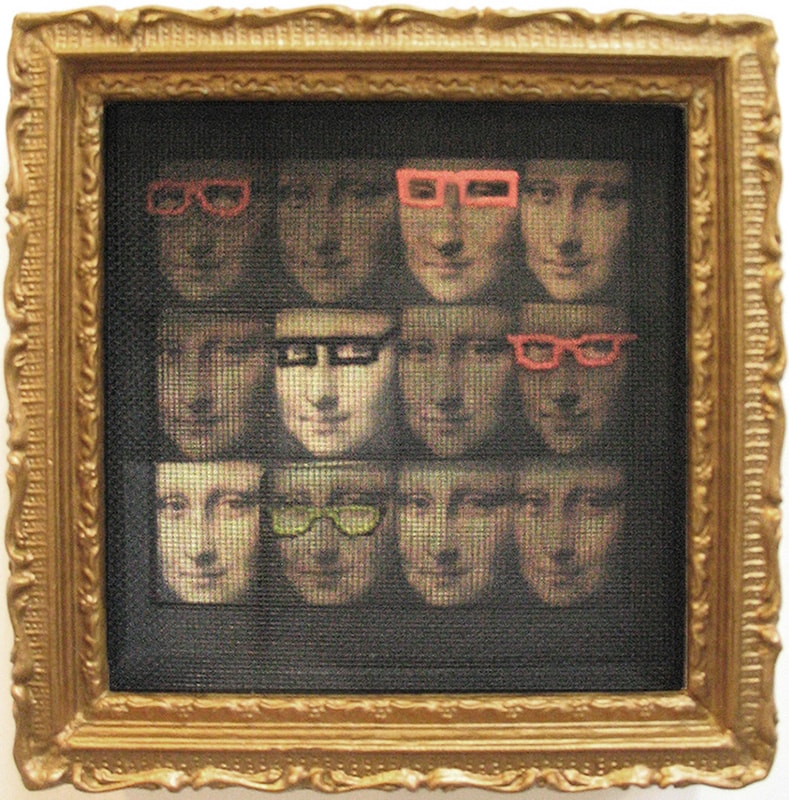

The Usual Suspects: Presto-Chango, Caught Red-Handed, Empty Rhetoric and Sideshow is about the clown show that happens in politics these days.

The Usual Suspects, 40” x 54”, 2019.

The Usual Suspects, 40” x 54”, 2019.

Contact:

Paula Kovarik

paulakovarik.com

IG: @yellowbrickstudio

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, February 2020

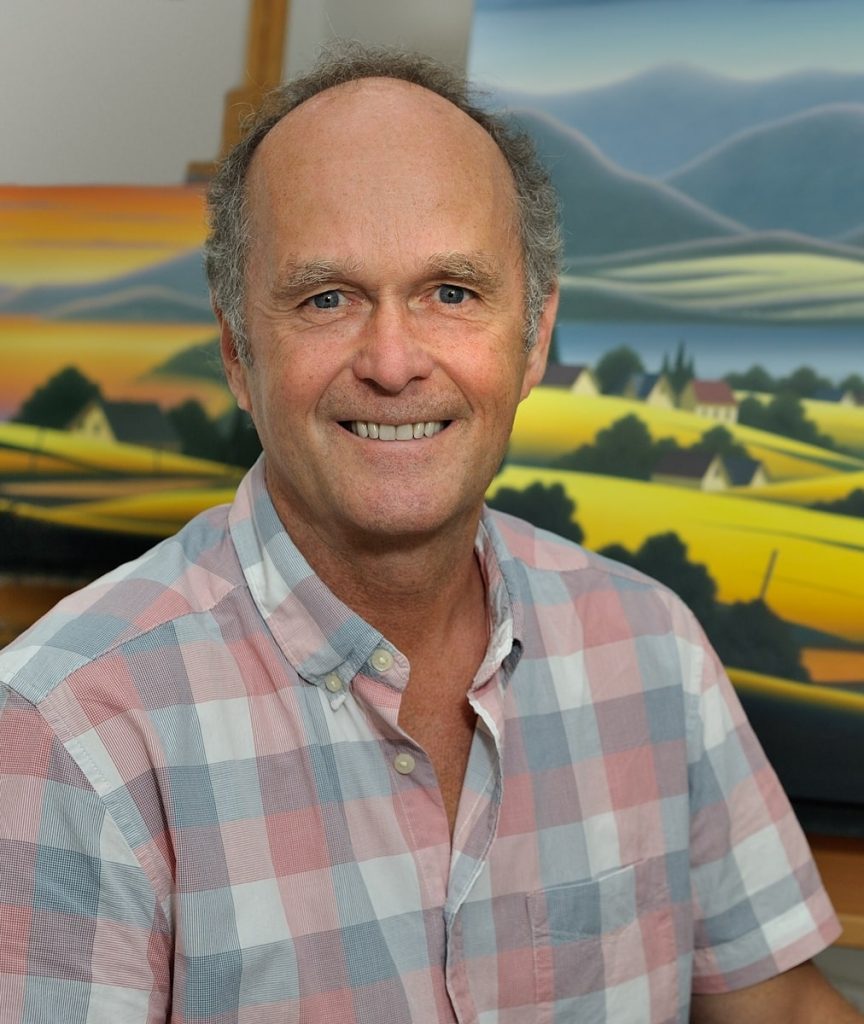

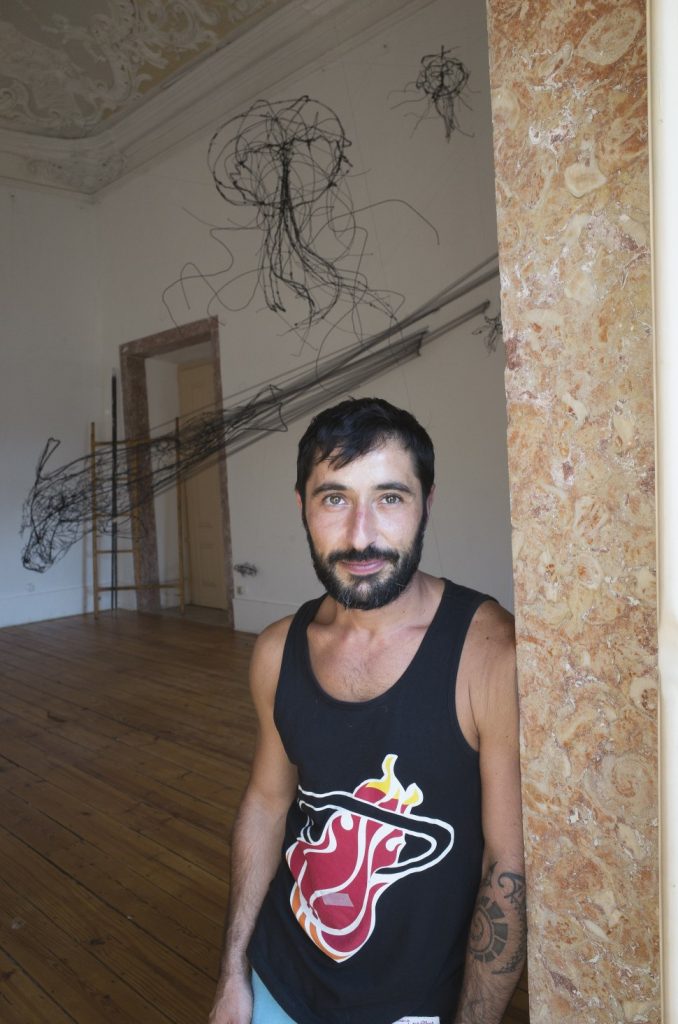

Peter Minson

You are a third-generation glass blower. Did you ever consider another career away from glass?

As a 13-14 year old I would go to the factory in school holidays to earn pocket money and when I left school at 16 I started full time. At 19-20 years I was managing the production of medical and scientific glassware and 21-22 years, hire and fire as they say. Not something I liked doing, firing someone but required when needed. A fast learning curve at a young age of handling people and handling staff majority were women. Looking back, I was always going to be a glassblower and follow a family tradition.

As well as your artistic glass blowing you sell glass and glass equipment from Italy. Why Italian glass and equipment?

As well as your artistic glassblowing you sell glass and equipment from Italy. Why Italian glass and equipment?

In the early 90s I was being asked to teach glass beadmaking sometimes in the Glass Department in ANU Canberra. The best glass for this was made in Italy, Venice on the island of Murano. I had written to the owners asking to import direct to Australia but they advised me to buy from their USA distributors.

The best range of glassblowing torches, burners for Lampwork were made in USA. I was awarded a Winston Churchill Fellowship in 1995 so while away in USA I organized to bring burners, hand tools in from a supplier and while in Europe I made a point of going to Murano, organized a meeting with the owner and after a discussion they agreed to supply me direct into Australia.

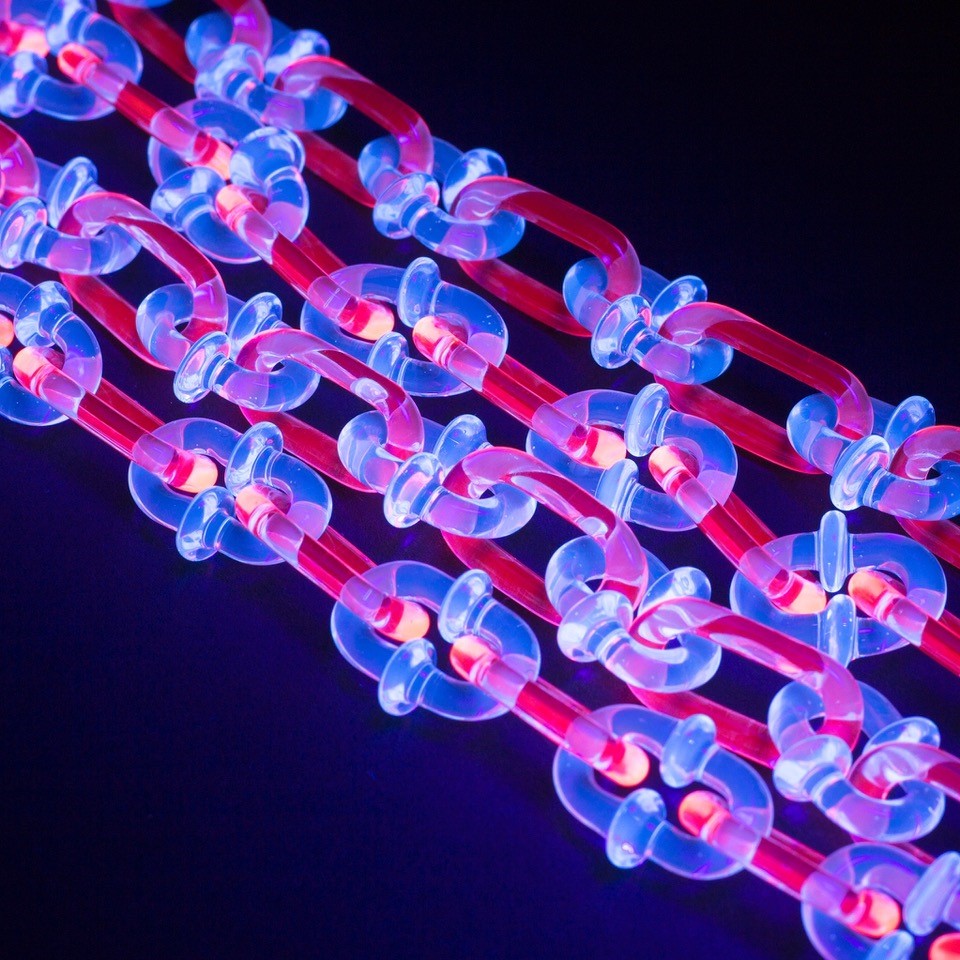

Explain about your Aventurine Chips and how they are used in glass blowing?

Aventurine is a form of Saturated Copper Glass. It comes in chunks and it is broken down into different size chips and powder. It comes in 3 colours, sparkling gold-brown, blue and green. It is used to decorate glass beads mainly giving the beads a sparkly look in surface treatment or when encased.

When the glass is molten hot, roll the bead, object over the aventurine chips which stick to the glass, reheat in the flame and it combines with the glass. To give depth a form of surface treatment, encase the chips with a layer of clear glass and melt in.

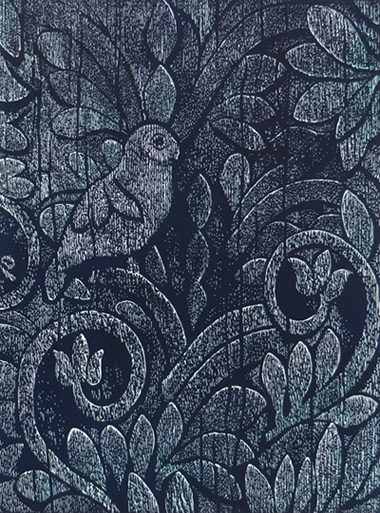

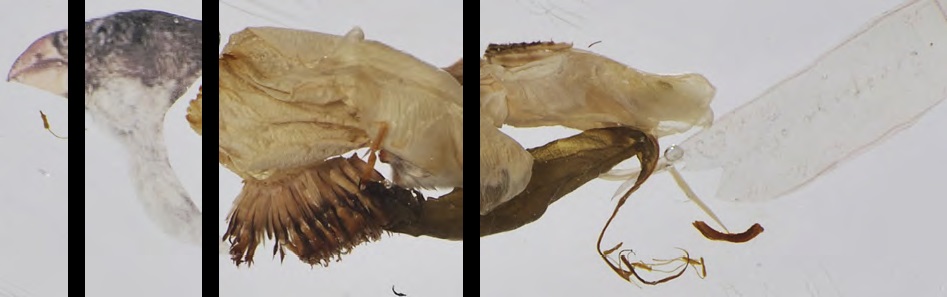

Explain about your work related to birds.

I have always like Birds mainly native birds, so colourful and interesting shapes and sizes. I decided to include them in glass items I made, on the stem of wine glasses, teapots, just free standing mostly trying to get their colouring correct especially showing the difference between male and female in the same breed such as Kingfishers. In 2002 I was approached by Niki Savvas an Australian Installation Artist working and exhibiting in England to make something in glass that would work with, complement her work in her next exhibition being held in London. It had to be something that had size and height and be simple. I came up with Birds, no specific breed just have good shape and height, long necks and legs, free standing in a number of positions. I made a sample, Niki liked it and commissioned me to make 12 and could I get them to England in 2 weeks time. They were successful and I was asked to make more for another exhibition and could they be the same with a bigger variety of stances and some taller. Most were around 500 mm tall and I managed to make some a metre tall.

The birds are made free hand from Borosilicate tubing and rod. I work from drawings or photos of birds. I blow the body shape then heat a section to draw out blowing shaping the neck and head. I join onto the body the top section of both legs. Next I shape and seal the tail. Then I add the bottom section of the legs. I let cool then add the feet getting them in a position so the bird has a correct stance to balance.

I live in Binalong country N.S.W. We are surrounded by birds, Magpies, lots of Parrots, Kookaburra, Sulphur Crested Cockatoo, Corellia, Wrens they are in our backyard in fact we are surrounded by them all the time.

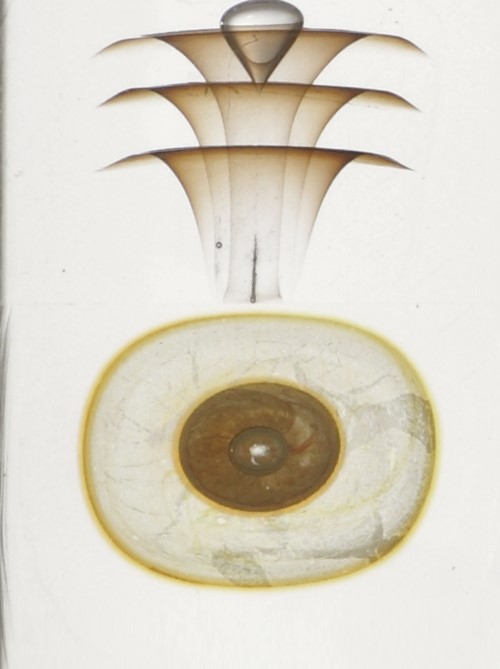

Take two or three of your glass lamp pieces, discuss.

For many years I have made Oil Lamps as a variation on having wax candles on a table. It was a natural extension to make blown animals with a fibre glass wick filled with lamp oil could be used instead of candles. Dolphins and Whale shapes look good and appeal to people. They relate to them.

I found that adding a dye to colour the lamp oil added another dimension. Different colours appeal to different people so gives another selling point and attraction. They can see where it will fit into the decor in their house.

With particular animals such as Dolphins, Whales blue lamp oil attracts customers and complements the shapes. Our lamp oil is fragrance free, some people can’t handle fragrance and others like different ones. We suggest they can add a fragrance they like.

You have designed many teapots. Explain about this aspect of your work.

Over 30 years ago following on from a conversation with a few Potters about Teapots, the difficulty of making a good on that works well, I decided to see if I could make a Glass Teapot. Made from Borosilicate Glass ( Pyrex) which handles boiling water easily, doesn’t conduct heat very well should suit a teapot.

It took almost a year experimenting on shape and size. Making a spout that poured correct, doesn’t drip and then a lid that stayed on when pouring but was simple to make. Quickly I found out that size was important, the customer tells you this, how many cups of tea does it hold, does it pour well not drip, the lid fits and stays on. The handle stays cool so easy and comfortable to hold.

Over the years I have made variations on the shape but really the basic round slightly squat shape is most popular, customers relate to, and just a small line of a few colours, blue, red, green, black on the opening and lid satisfies most customer. We have a little Café here in the Gallery and use my Glass Teapots when serving a pot of tea. People love that we serve their pot of tea in a glass teapot I made and it works.

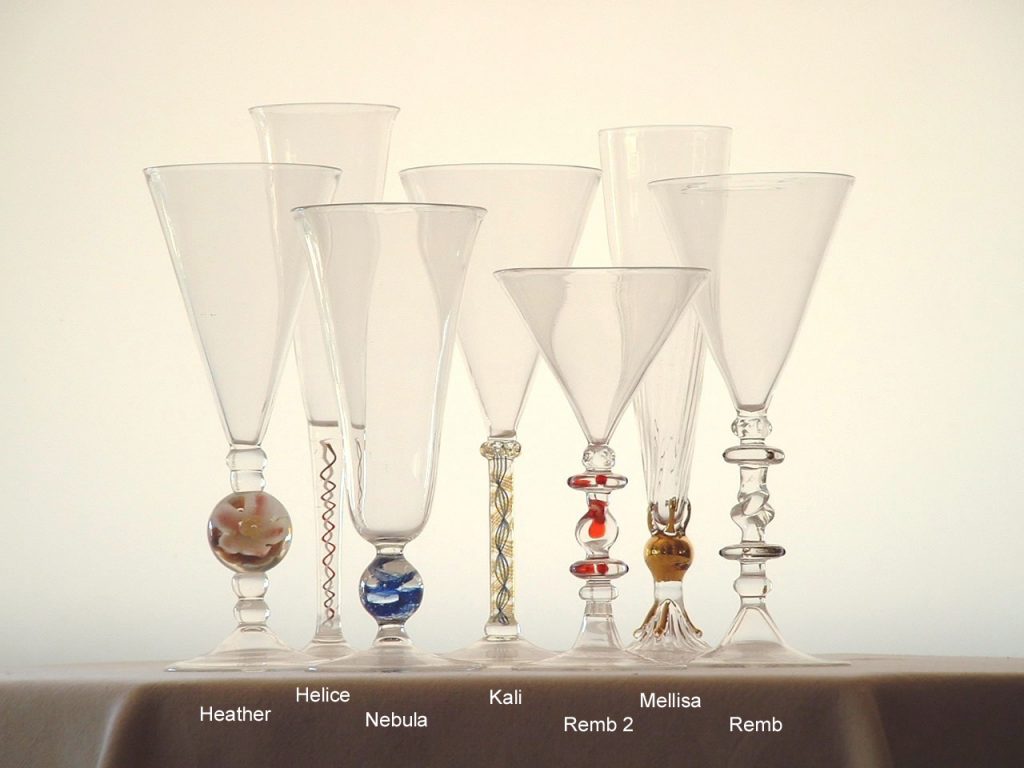

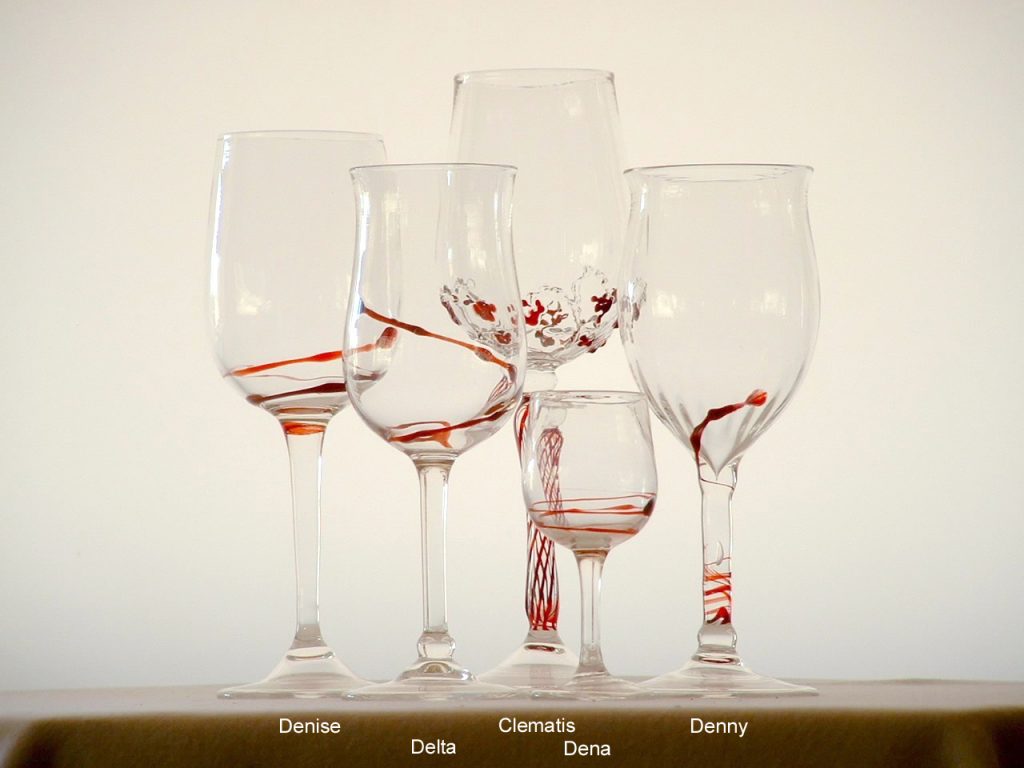

How have you worked on the beauty of stems in your glasses?

A wine glass is made up 3 parts, bowl, stem and foot. Each part must complement the other, balance to be good design. So in making a wine glass I think on what type, style of wine it will be used for. Reidel, an overseas glass company makes a different shape glass for every style of wine. So shape and size is important.

Adding a pattern to the bowl adds another dimension visually especially a pattern or colour. Serious wine drinkers like clear glass, no colour as it detracts from the colour of the wine however I have found if I use minimum colour, a simple line or fume the bowl with silver the reaction with the glass, light, sun shining on the bowl can react with the wine colour, bubbles and add to the enjoyment when using.

The stem allows me to experiment on shape and colour, still having to complement the bowl and foot. Looking at glass drinking vessels in books made over the centuries, can be very humbling and inspiring at the same time. Certain periods come to mind such as the English “Georgian Period”. Recently I did some work for the National Trust, they had a recent donation of a private collection of Georgian drinking vessels and I was asked to speak and explain at an exhibition they were showing. Very humbling to see the quality, styles and variations made so many years ago. In trying to equal those, challenges me, understanding type of stem, air twist etc and trying to replicate using a different type of glass working a different way and yet must look good and do the job. Getting the stem right is a big part of this.

Finally making a foot to balance, complement the bowl and stem can make or break the design and so attract or distract from the Glass. Getting this right is as important as the other parts.

You still do classes. What have been a few highlights from your interaction with students?

I love teaching, especially Lampwork. I get great enjoyment in teaching people to work with glass as I do with a bench burner, glass tubing and rod in either low temperature, soft soda lime glass or high temperature hard Borosilicate glass. To take someone who has never worked with glass especially Lampwork, to see them gain hand skills, glass knowledge and confidence to make their ideas, be creative and get good results, nothing better for the student and teacher. To see them having as much fun and enjoyment as I do each day is very satisfying. I have been doing this for a long time, worked in all areas and forms of glass, Lampwork, fusing and slumping, casting, engraving and cutting, building furnaces, making the glass to work with and then using it to make functional or art glass, always glass the best material, most challenging of materials.

How as an artist do you relate to commissions?

A commission is always a challenge. If the client has a drawing or photo of what they want makes it easier, but not made in glass and they want it in glass. If they don’t have either I have to understand what they want and why.

What I try to find out is what they don’t like be it shape, size or colour. Then I try to make what I like based on what we have discussed trusting I have understood enough to create something they like also. Luckily I have managed to get this right over the years.

Take a recent commission and explain the involvement between you and the client.

There have been a number of Commissions over the years, “International Riesling Challenge” Award, I have made these for 20 years, also a trophy for a one of game between the Aussie “ Matildas” and the N.Z “Silver Ferns” celebrating 100 years of creating the ACT and Canberra. Luckily the Australian women won and is proudly displayed in a cabinet with all the other trophies they have won.

The most recent was a trophy for a “Signing” group, a perpetual Trophy where the winner get their name and year engraved on the base and a smaller version for the winner to take home.

“Signing” is where a person uses hands to talk through hand and finger shape and movement. Firstly I had to understand what “Signing” was and the importance of the “Clasped Hands” symbol. My friend who works in Metal collaborated. Looking at what I had made in glass, clasped hands with wrists, he made “Shirt Cuffs and a Button”, my wrists fitted perfectly into his sleeves cuffs with buttons complemented and completed the trophy.

I was happy, he was happy and the Client very happy. Now each year hopefully we will get a repeat commission to make the smaller version for the winner to take home.

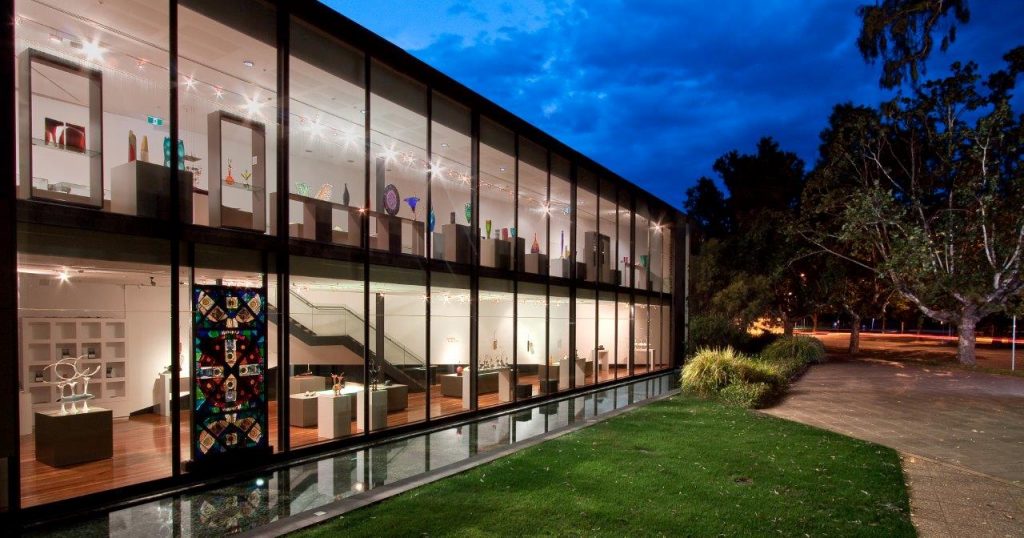

Recently you have had a retrospective at the Wagga Glass Gallery expand:

Your involvement with the Gallery

In 1981 Wagga Wagga Council advertised they would be holding an exhibition to showcase Australian Art Glass. They advertised nationwide and attracted entries from all over Australia. I received an entry form and sent some of my furnace work which I was making in ‘The Paris Creek Craft Workshops” S.A. My work sold to private collectors. In 1982 they ran another exhibition and this time my work was purchased to be included in the newly established National Art Glass Collection.

The value of glass to Wagga

In 2016 I was asked to open the exhibition celebrating 35 years of the National Collection”. I spoke to those attending how I saw the importance of establishing Collecting Art Glass in the early days for the Art Glass movement in Australia, and how over the years by adding to it had given it importance to desire to everyone working in glass to develop their work to international standard be equal to Art Glass made anywhere in the world and maybe become part of the Collection. This has happened and Australian Art Glass is equal to anything made overseas.

With my official duties done I spoke to the Mayor thanking the Council for supporting the Glass Gallery from inception. The Mayor assured me they would always support the Collection. Every year at budget time they have a meeting to decide where they will spend their funds initially looking at 5 core sections first and after that money goes to other areas as decided on need. In those 5 core sections each year the National Glass Collection Gallery is always 3 or 4 in importance to Wagga Wagga just in the number of tourists that come to see the collection from all over country and from overseas means they will always support the Gallery.

How did the Regional Gallery establish it connection with glass?

Back in 1978 a number of people started an organization called Ausglass to give a place for people working in glass a place to meet and talk about glass. In 1980 2 people who lived in Wagga Wagga had noticed the beginnings of this Art Glass movement, one John Elswood the other Judy Le Livre and decide to hold an exhibition to celebrate this. The first exhibition was in 1981 and work exhibited purchased by the Council and newly formed “Friends of the Gallery” and donated back to the Gallery were the beginnings of the Collection.

Contact:

Peter Minson

peter@minsonartglass.com.au

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, February 2020

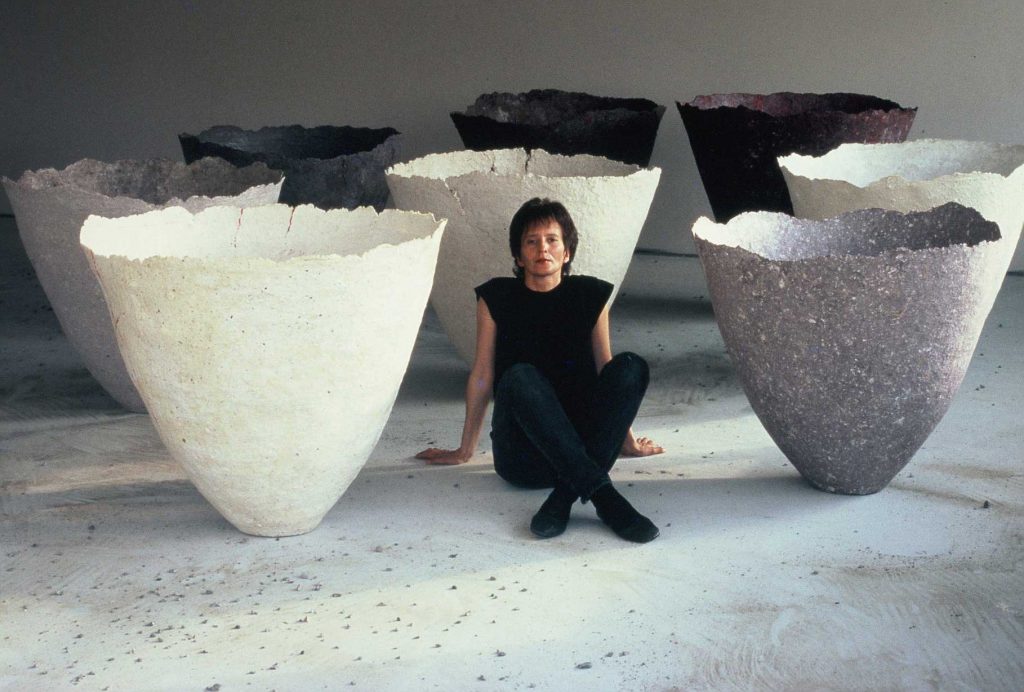

Pamela Sunday

What, lead you to leap into ceramics full time?

I entered the world of ceramic serendipitously. A group of friends were searching for creative ways to socialize. It was the "Sex In The City" era, and we opted for creativity over cosmopolitans, I fell in love with the material of clay and the process of blending it to my will. It was challenging and scary to leave behind a successful life in fashion, but my passion for clay won out. I was fortunate to have design magazines to take notice of the work early on.

Now looking back on this move what have been two highlights?

One major highlight was a commission from Francois Catroux, the legendary Paris based designer. I was challenged to make a group of huge iterations of my Electrum Series. It was necessary to balance the new scale with the delicacy of the points. I spent many months experimenting and relearning the form, discovering how to make it work on a larger scale.

Another highlight was a feature in German Vogue. They ran a full-page portrait with my work and lovely interview, resulting in a whole new level of exposure to European collectors.

Many artists have been propelled by time at Anderson Ranch Arts Centre – how did your time there nourish you and your work?

I took a workshop at Anderson Ranch in the mid – 1990’s with the renowned Tony Hepburn. The experience of total immersion there, in a group of obsessed cohorts and teachers, was the impetus for setting up my first studio. The envoromnent gave me permission to consider myself an artist and make a full – on commitment to my future.

Discuss the importance of excellent photography of each piece.

Relate this back to your time as an Art Director and Artist.

I spent a decade working in the advertising department of Bergdorf Goodman. My aesthetic and work ethic developed there.

My husband, Paul Sunday, photographs most of my work. He is known for his beautiful lighting (and patience!). I was lucky to have publication – ready images from the beginning of my career.

How is nature and science represented in your work?

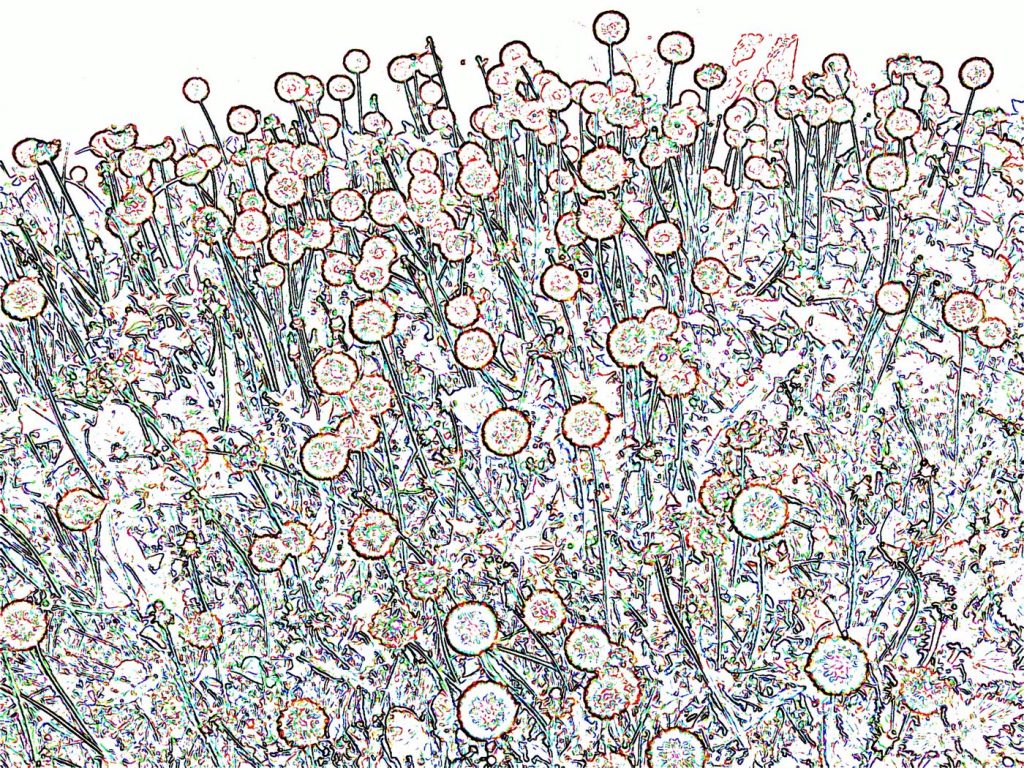

I take inspiration from the images of microscopic life, scientific illustrations, historical references, and photography. The endless permutations and possibilities afforded by the recurrence of the orb in nature will no doubt continue to sustain my interest!

MOLECULAR: 19” high x 15” wide/deep: glazed stoneware

MOLECULAR: 19” high x 15” wide/deep: glazed stoneware

Please discuss the technique you use to make your work.

My sculptures are made by joining repetitive elements. Some components are formed on the wheel, and others are made using an assortment of hand-building techniques. I have a habit of pushing the tolerance of my materials to the edge. Each piece takes many weeks to complete. My process is an exercise in endurance and tenacity.

HIVE: 15”x 15”x 15”. Unglazed brown stoneware with lustre in indents

Discuss the importance of prominent pieces in an architectural setting.

When a sculpture can attain presence in an architecturally significant space, both are transformed into something more thrilling and memorable.

What size limits do you have?

There are no limits. Things keep getting bigger, it would be fun to see where I can go next.

Does all, of your work have a metallic lustre?

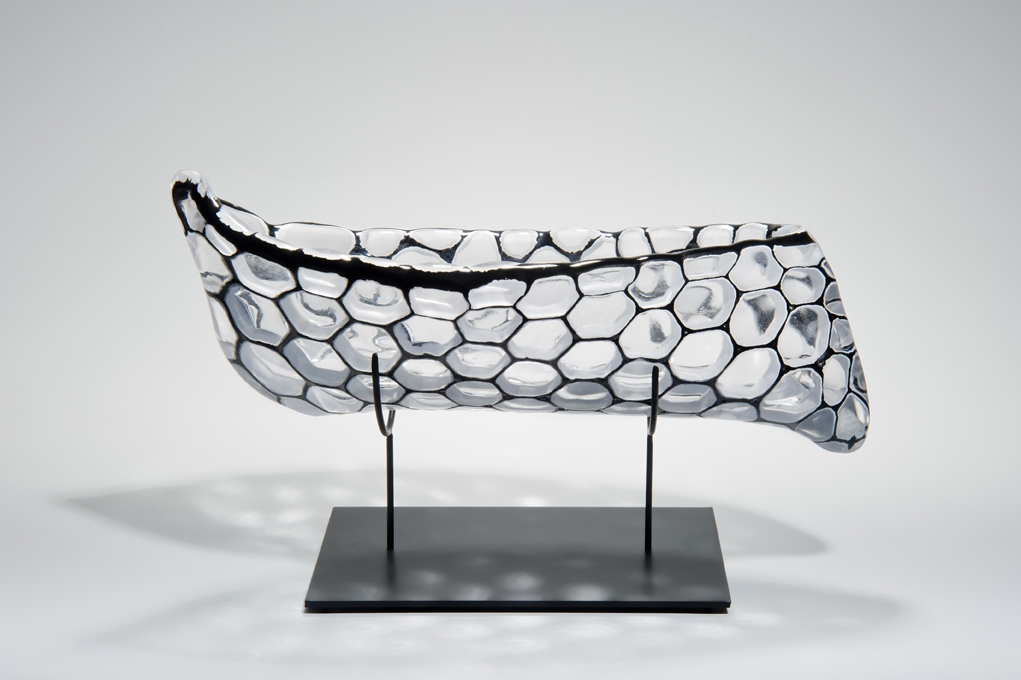

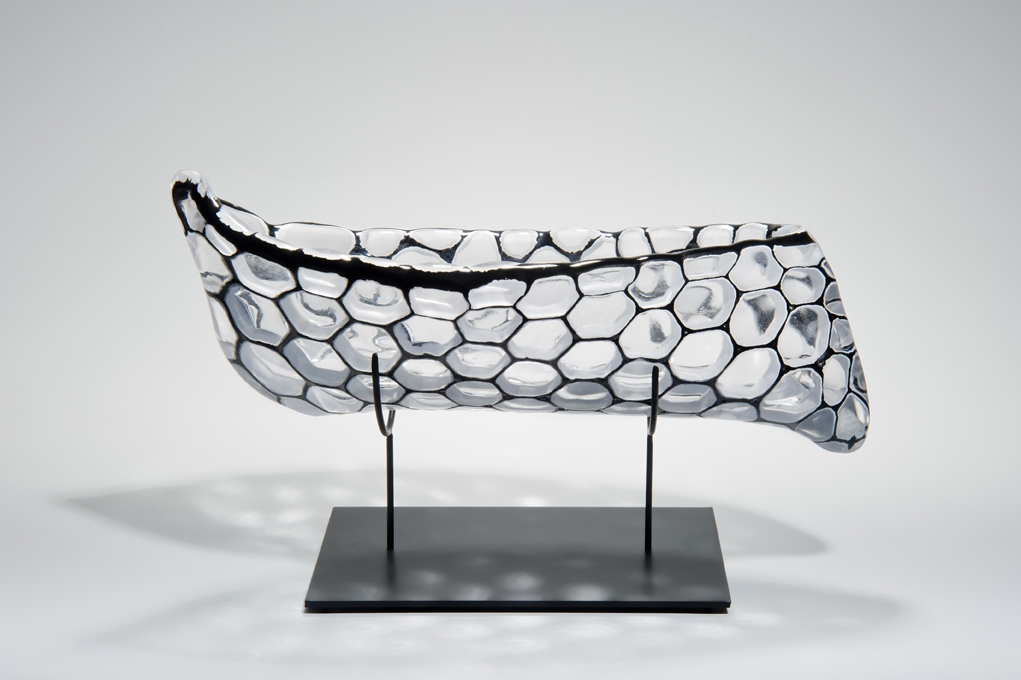

SAEPIO: 24” long x 19” wide x 12.5” high. Glazed stoneware

I love glaze chemistry; it’s a big part of the fun for me. I will always be developing new surfaces. While I have often gravitated toward metallic glazes, lately, I have been exploring rich glossy blacks and reds. My early work was often matte and textural. For me, it’s about pairing the form with the appropriate surface.

MOTUS: 19” long x 16” wide x 11.5” high. Glazed stoneware

Shape is a huge aspect of your work – take two or three pieces and expand on your use of sharp and soft shapes.

Stella:

Every aspect of this form is planned, the central sphere, three sizes of attachments, and the placement / balance of each component. I hope that it looks organized and organic at the same time.

STELLA: 14”X 14”x 14”, stoneware with satin metallic glaze

Rubrum:

This piece explores a new direction, exploiting a generative strategy, and asymmetry. It’s a different way of working but the orb is still the foundation.

RUBRUM: 24” long x 13” wide x 9.5” high. Glazed stoneware

Do you ever have work sold in series or collections?

Yes, on occasion, collectors have commissioned pairs or groups of works. The new generative experiments could lead to more of this way of thinking. The possibilities for groupings, series, and installations are endless.

Contact:

Pamela Sunday

Pamelasunday.com

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, February 2020

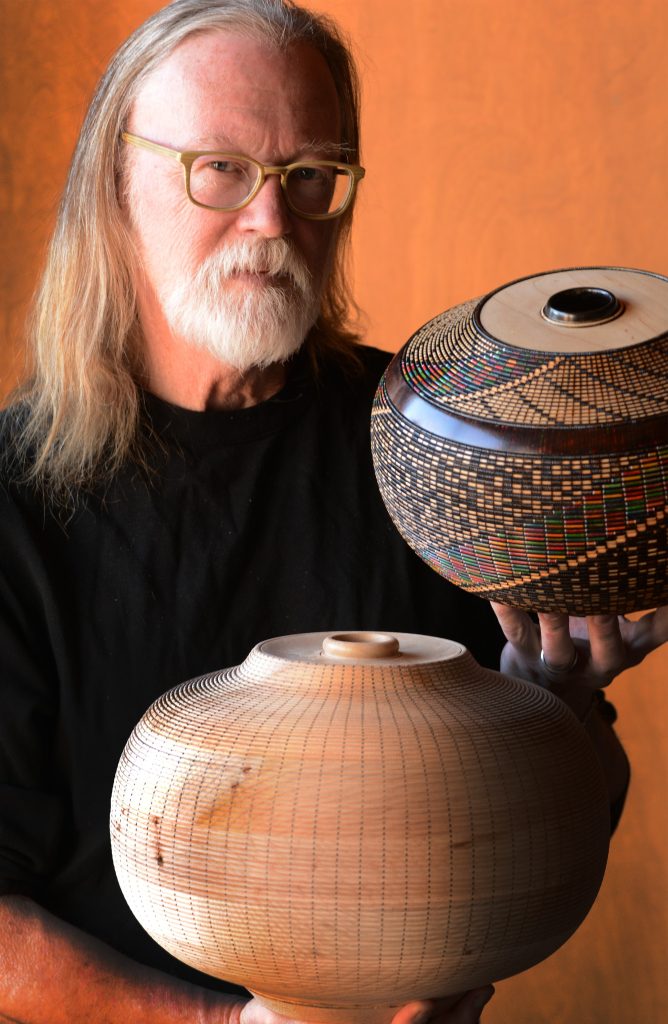

Keoni Carlson

Your work is an illusion. Discuss

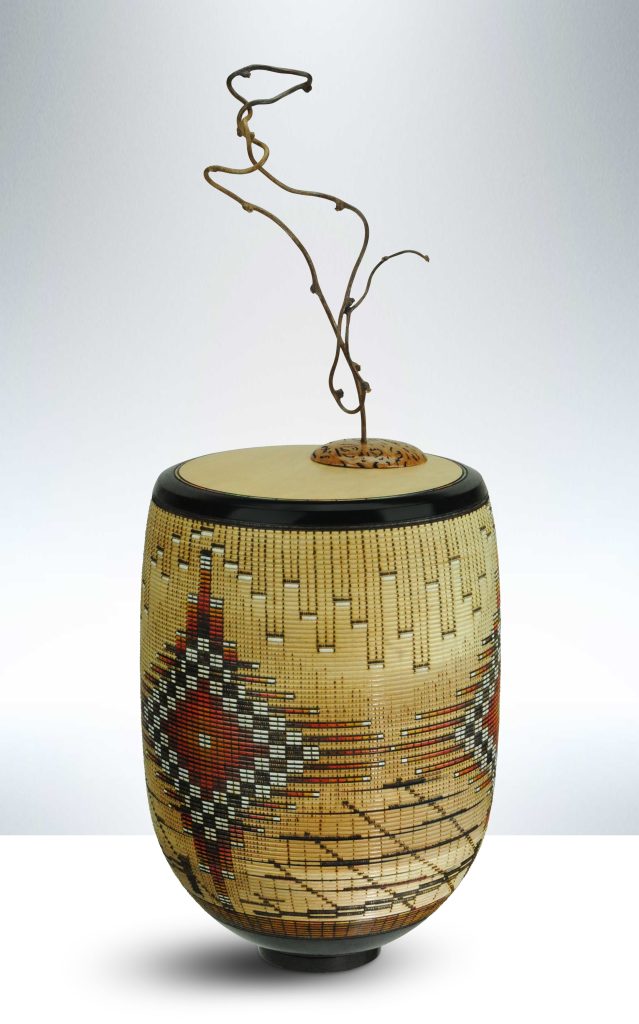

Illusion work involves using one medium/material to look like another. In my case, I use wood to represent the “illusion” of fabric and/or beadwork.

Copper Mountain, 8"h x 9"d vessel, Sugar Maple, woodburning, india inks, organic dyes and metallic inks

What have been some of the comments made by viewers when they realise it is wood?

There are very common reactions:

- . it’s really wood… didn’t believe it

- It must take an immense amount of time (yes, it does)

- I thought it was woven basketry

- Never saw the technique before

- How is it done?

Sky Dreamer, 28"h x 9"d tabletop sculpture, Sugar maple, kiwi vine, red mallee burl, woodburning, india inks

Sky Dreamer, 28"h x 9"d tabletop sculpture, Sugar maple, kiwi vine, red mallee burl, woodburning, india inks

You have only been working on this technique since 2017. Where did the inspiration come from?

The practice of illusion carving is quite old: think Europe and the great Cathedrals where wood was carved and gilded to suggest stone; and then in China and Japan even earlier where stone was carved to mimic wood. Artists of respective regions using available, local materials to create the illusion of more scarce sources.

I saw the techniques demonstrated in the early 1990s then revisited the style in 2003/2004, particularly influenced by the work of Lincoln Seitzman and Jim Adkins and then later by artist David Nitman. With my retirement in 2017, I was able to begin exploring the technique in ernest.

My love for the Lathe began as a young boy when introduced to the tool by my father; I was a hobby woodturner from that time forward. The journey to professional artist was accidental and organic, the evolution paced by unexpected opportunities and encouragements from family, colleagues and patrons.

Preparing the canvases

Preparing the canvases

You are a 3rd generation wood carver. What do you think your forebears would have to say of your art?

My hope is that they would be proud that the tradition of working with wood has continued. My family’s backgrounds were more as builders and carpenters… and the very practical world of the Mid-West and West, that I have found a niche as a wood artist would have both surprised and satisfied.

Contemporary wall sculpture, 22"d; "Eagles". porcupine quill center.

Can you tell us where some of the very best woven baskets can be seen and in which museums or galleries?

“Best” is so subjective. Examples of the technique can be found in collections at The Smithsonian Museum and western art collections of museums such as The CM Russell, the Briscoe and the Eitlejorge, all in the US. Collectors range the world stage as do galleries that showcase Southwest/Western fine craft/fine art.

I’m honored to have been selected as a 2020 Smithsonian artist and will join 120 others next April in an exhibition and public sales event in Washington DC.

Discuss the importance of keeping American Southwest tribal culture alive through your art.

Joseph's Coat: 8"h x 9"d vessel, Sugar maple, woodburning, india inks

My artwork is story-driven, an approach that I believe adds meaning and context beyond the wood art itself. I spend considerable time researching Native Cultures’ storytelling, legends and iconography. This provides a foundation for my eventual contemporary design interpretation.

Do you provide, an explanation of the story related to each piece?

Yes, of course… for any of the larger/major pieces. The story informs the piece and adds depth and meaning. I want to be sure my customers are able to tell their friends about the story of the artwork.

Sol Via, 15"d x 2" wall sculpture, Sugar maple, woodburning, india inks

Sol Via, 15"d x 2" wall sculpture, Sugar maple, woodburning, india inks

Comment on the marriage, of the two aspects of your work. Traditional wood carving and storytelling.

My work is story-driven… at least for the major and larger pieces. (small ones are just pretty (grin). I believe that the aspect of “story” adds much to the production of each illusion carving. “Story” is one of the things that sets my work apart. While patrons are drawn to the beauty and uniqueness, it is often the story of a piece that results in selection and purchase.

Sonoran Triplet: Dawn, Midday & Dusk, each platter is 10"d x 2"h, Sugar maple, woodburning, india inks

I do detailed research (thank you Internet) on tribal/Native Culture stories, legends, iconography and mythology. I have a degree in Library Science so am experienced in the process of detailed research; as well, my degree and earlier profession as a journalist also fostered my love of story… a grounding my entire life.

There’s an emotion to story that compliments the artwork

Once I’ve identified a story or aspect, then I interprete it into imagery that I can carve and color. All this is done freehand when sometimes a small bit of sketching. I don’t do detailed patterns or drawings prior to starting to carve. The spontaneous, organic nature of the interplay of carving and wood provide a one-of-a-kind direction.

Detail shot: burning the design

What has led you to use sugar maple? Sugar maple is used for a very specific reason. Because I woodburn the designs at a very high temperature… the combination of heat + the sugar content of the wood itself produces a wonderful patina of soft browns and ivory as the cell structure actually carmelises.

You also use reclaimed or re-purposed maple. How difficult is it to source?

In the American late 1940s/1950s, furniture manufacturers used hardwoods such as Maple, Cherry and Oak to produce large volumes of functional furniture. Over the years, much of the work was handed down and eventually has found its way to flea markets, 2nd hand stores, etc. I look for these damaged, well-worn pieces and salvage wood. Another source is rail car flooring. Hardwood planks were inexpensive to use and the American rail industry expanded. Now many of the old freight boxcars are being scrapped and flooring recycled.

Patterns are represented using colour of the weave or beads that would have been woven into the baskets. Briefly can you explain how you do both techniques.

The woven technique involves woodburning a very high number of cuts in very fine-line detail. All the woodburning is done with a single tool… a 1/8” radius. By varying the pressure, the temperature and the density of strokes, I can create the illusion of weaving and fabric… even when looked at closely. From any distance, it’s difficult to believe “…it’s wood..”; For the woven designs that require color, semi-transparent India inks are applied. The transparency mimics the appearance of colored fabric. Inks are applied with brushes and solvent washes.

Ohana (family in Hawaiian) 14"H x 9"d vessel, Sugar Maple, woodburning, India inks

The beaded technique is again woodburned using the 1/8” tool. Actual beads are opaque in color. To achieve this, I use organic, solid dyes rather than the transparent inks. These dyes are actually applied twice. The first application of color soaks into the wood to produce a muted color effect. Can be nice but beadwork is opaque so a 2nd color coat needs applied. Each cell is colored discretely so that color does not bleed from cell to cell.

Can you expand on the inside of your baskets?

For some hollow-form executions, the vessel opening is large enough that the inside is visible. When this is the case, I woodburn and color the inside. This more than doubles the time required to finish the piece. As well, the entire inside must be finished first, then the outside of the piece is shaped to final form, carved and colored.

How do you sign your work?

I sign with my artist name: “Keoni”, the year a piece is produced, the name of the piece, and the studio location (either Colorado or California); On major pieces I also include a design reference number.

- I’ve became a professional artist (or at least started the journey in 2017 so have been at it for only three years at the professional level. Many fine this short time surprising.

- My success trajectory has been unexpected.

Year 1: Acceptance into a top tier art show; one gallery representation; several national awards.

Year 2: Full schedule of national, top tier art shows; nomination to the By Western Hands artisan guild; exhibition acceptance at The CM Russell Museum; multiple awards; additional gallery representation.

Year 3: Acceptance to the 2020 Smithsonian exhibition; SOFA-Chicago exhibition; refined, full schedule of top tier art shows; publicity coverage in several national publications ; refined gallery representation.

I believe my business background facilitated the fast start. Of course, the artwork had to be of commercial quality… but my understanding of the marketing, finance and business aspects was not a struggle… I’ve honed those skills with decades of a business career. I understood from the start, the need for branding… efficient material sourcing… differing customer sales channels… the value of publicity… tiered pricing… etc.

I often refer to myself as an “accidental artist…” as this current journey wasn’t at all planned. No art classes… no formal artist training…

I remain young and learning. Most every experience is a single data point, whether that be a gallery interaction… set-up and selling at a national show such as Philadelphia, Chicago or Smithsonian…

I am blessed many times over: my wife and life partner, Karen, is amazingly supportive; artist colleagues that freely share advice, experiences and hard-won knowledge… retail and gallery owners that, even in rejection, offer encouragement… and the many, many patrons that validate my work with each and every purchase.

Journey, wall sculpture, Leopard wood/stainless steel accent back: 24"h x 18"w Medallion: 13"d x 3"h

Contact:

Keoni

KeoniWoodArt.com

KeoniWoodArt@gmail.com

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, February 2020

Susan Brown

You used to paint only in water colour, recently you have been working in acrylic too. How do you find the two mediums?

I had to reverse my brain when working in acrylic, as the technique is to go from dark to light (color), usually blocking out the dark areas in advance, whereas with watercolor, one must go from light to dark, usually leaving areas of white paper for the “whites.” It took me awhile to make the change when working in acrylics.

Another difference is the “happy accidents” one gets from watercolor—how colors blend “by themselves” (with a little help sometimes). However, watercolor is less forgiving than acrylic in that one can’t paint over what one has done—it was a revelation that I can make complete changes in acrylic just by painting over what I’ve done! Both watercolor and acrylic allow layers of color over another, though with slightly different techniques. Actually, I’m now able to switch easily between media, including oil as well.

Hidden Valley Summer, oil,14”x 16”

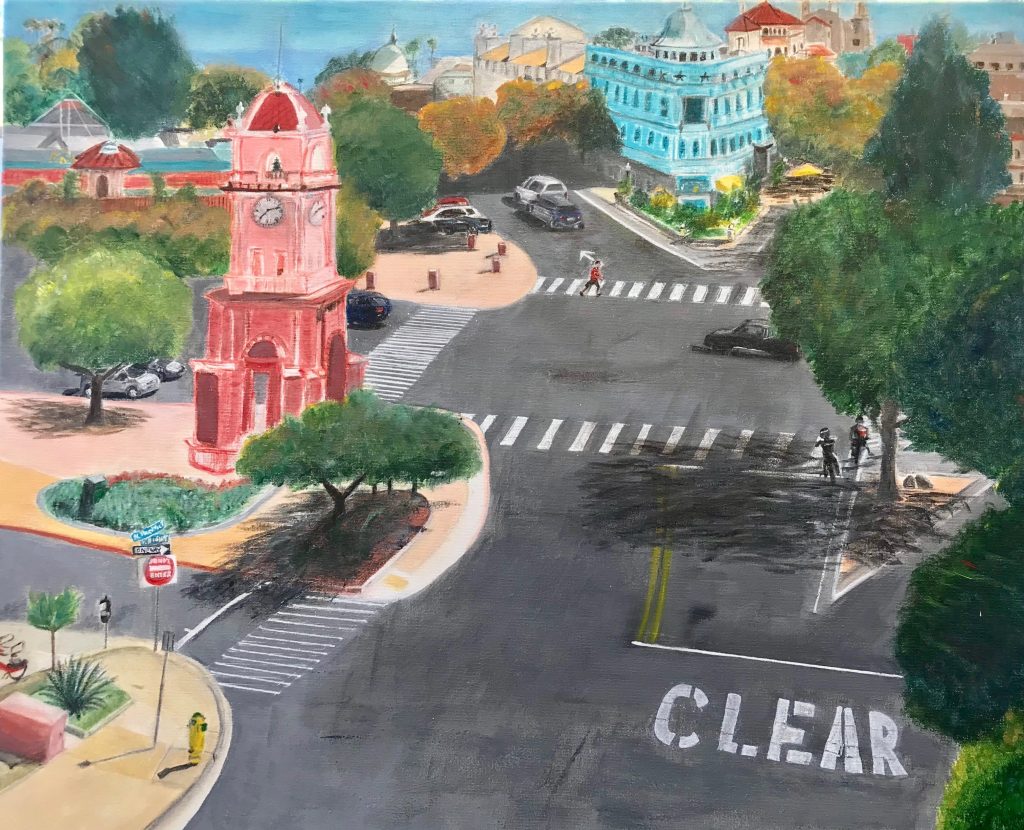

Comment on your series of Street scenes – Santa Cruz to San Francisco. Can you use 3 to 4 paintings and take us on the trip?

Discuss the content

Discuss differences in the environment you pass through

How you have used the physical road

Since living in the San Francisco Bay Area, and now Santa Cruz County, I have found in my street-scene/local landscape paintings a way to show my love of place and the deep emotional attachment I have for my CA home. This “location” series allows me to explore my fascination with the same location in various times of day and from different perspectives and vantage points. I enjoy the challenge of combining architectural details with city and rural landscapes and solving the geometry of space. My aim with these paintings is to share with the viewer this feeling of joy and warmth, and to evoke a deep feeling of place recognition, even if it’s somewhere you have never been.

Rio Del Mar, acrylic, 12”x 14”

After completing a small painting of Rio Del Mar, My partner, Rick, suggested that I continue and paint a series of local areas that are important to me. I’d never done this level of architectural/landscape mix, but I was inspired by Richard Diebenkorn’s paintings that combine streets, buildings and landscape.

The first painting I did in this series is “Van Ness Ave” —which is the street where I live. I expanded the view to include several iconic town buildings, a hint of the Boardwalk and across the Bay to Moss Landing. It was a challenge! I had fun painting the cars, including the ice blue one parked on the street, which is my own car. It turned out well and has been exhibited in several venues, as well as prints in private collections.

Santa Cruz Van Ness Ave, Acrylic, 18”x 24”

Next, I painted “Santa Cruz Downtown,” playing with the color of the representative buildings, including the town clock and the triangle building at the intersection of Pacific Ave. and Front St.; the main streets of the town. Another challenge, as this had lots of geometry such as the crosswalks and the angles of the street intersections.

Santa Cruz Downtown, Acrylic, 18”x 24”

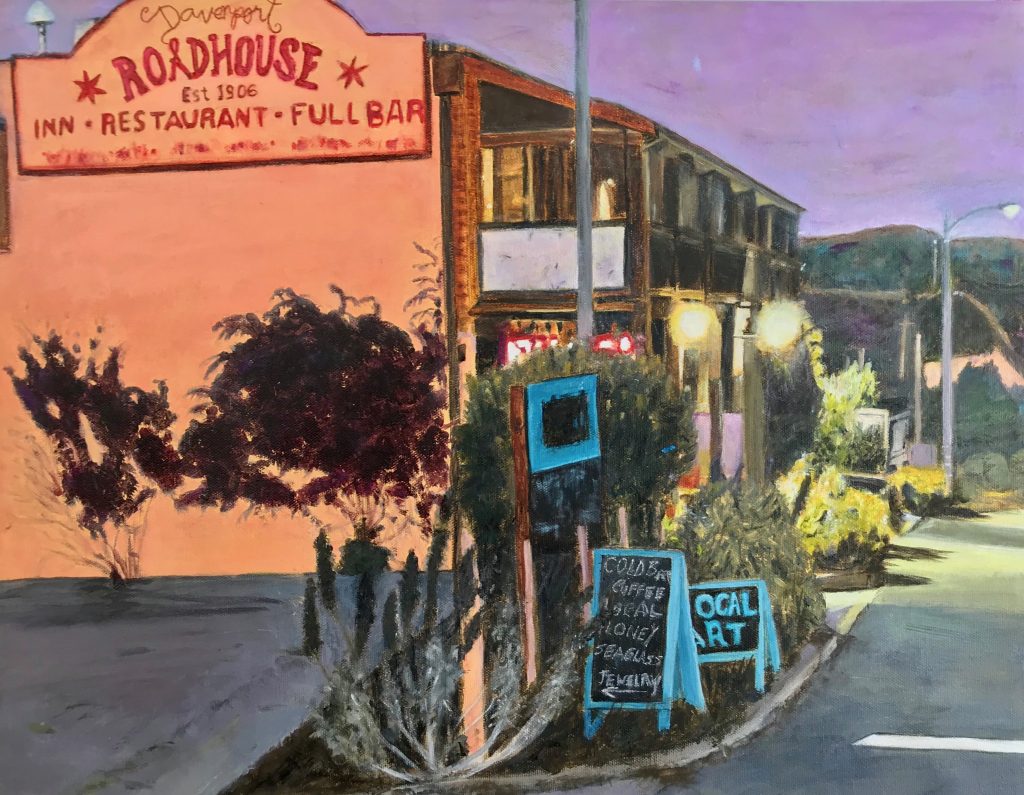

The next few paintings in the series are of various aspects of Davenport, CA—in different times of day and evening. Davenport is a small village with a few excellent restaurants, a country store and a famous glass blower. I’d been coming here for years to one of the restaurants, The Road House, and to Lundberg Glass before I moved to Santa Cruz, which is very close (10 miles) to Davenport. Now it’s a place I go to even more often, for brunch with friends, to walk on the bluffs, the beach and to explore the back roads.

Davenport Evening, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

I’ll finish our “tour” with "San Francisco”—featuring one of the steep streets this great city is known for. I moved to the SF Bay Area in 1978, and never tire of going to the city. Again, I played with color (the street is not really purple) (<* , form and geometry.

San Francisco 1, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

Discuss the use of colour in your flower paints also the use of cropping.

Color is the soul of all my paintings, especially the flowers, whether in watercolor or acrylics. When I was painting mainly in watercolor, I naturally gravitated to painting one or two “cropped” floral images as I was attracted to the form of each flower. I enjoyed painting watercolor flowers in large scope, including the peonies, which is the largest watercolor painting I’ve done; 36”X 24”.

Beauty, Watercolor, 12”x 14”

The flowers seem to float off the page, which was the effect I was going for. I used watercolor glazing to show the depth of the flowers and express the delicacy and elegance of the forms, and goache to contrast the opaque dark background and leaves.

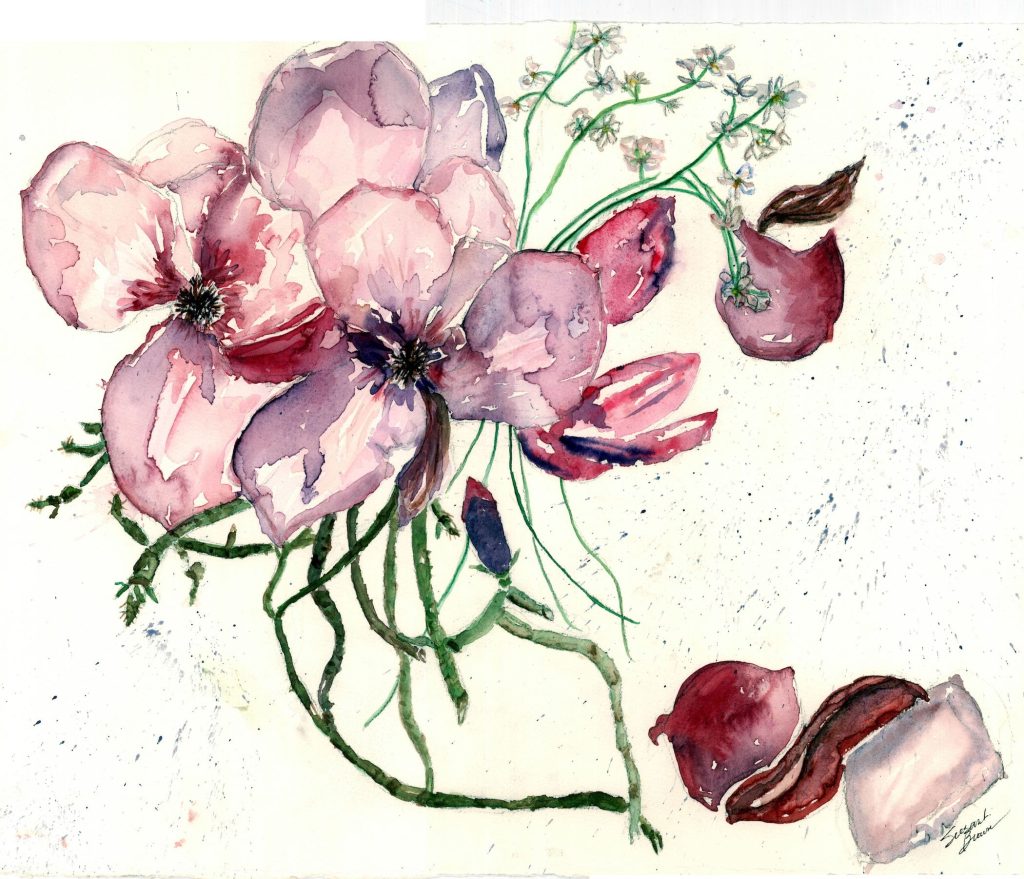

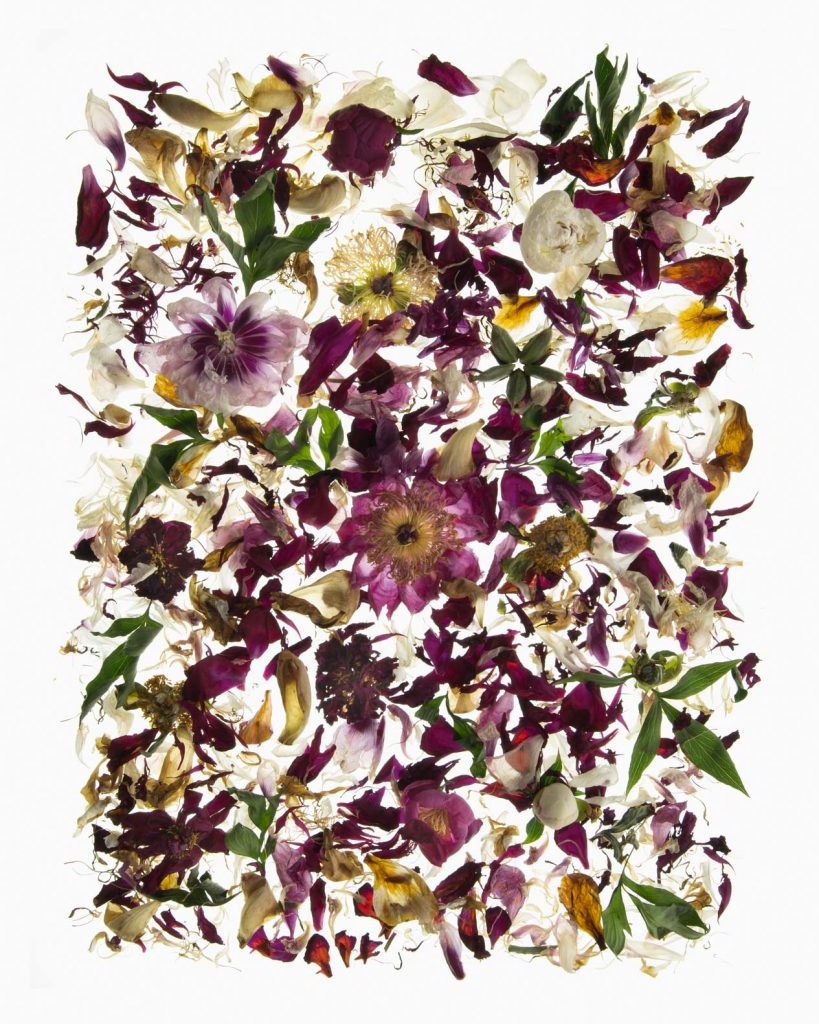

My magnolia watercolor paintings were inspired by Japanese floral paintings, including showing the petals as they are fallen off the plant. The symbolism is that the young and old are natural and inevitable parts of the same whole.

Magnolia 2, Watercolor, 16”x 20”

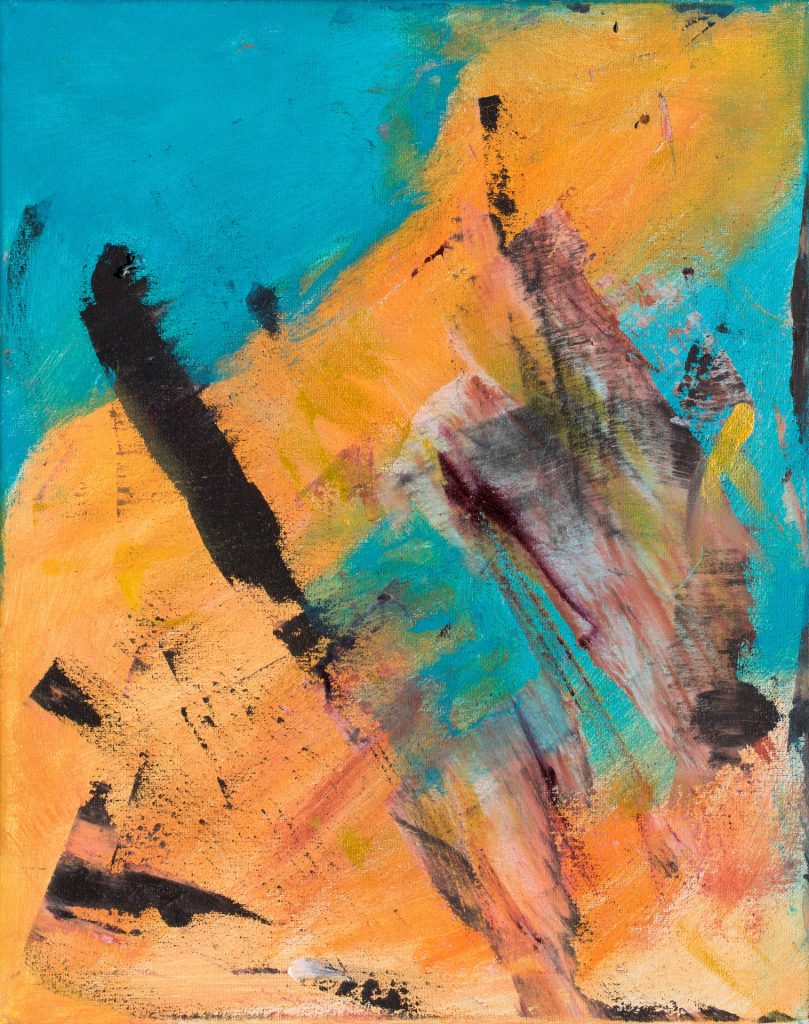

My acrylic flower paintings have more complexity and abstraction—using the elements of bold color and texture to which acrylic lends itself. It was fun to do them, as they are built on layers of background texture and color; the flowers themselves then added on top, even using my fingers to make effects.

Dream of Flowers, Acrylic, 18”x 24”

How important is colour in your abstraction work?

Color is my first instinct, then form and perspective. The abstracts are very fun and freeing for me, especially in contrast to the “Street Scene” series of paintings which are very “paintstaking,” full of geometry and detail.

Fire Dream, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

For most of my abstracts I start with lots of background color and texture on the canvas, let this dry, then add more color and shapes as I feel them. I sometimes use tools, such as squeegees in various sizes and large brushes to add texture.

A few of my abstracts, however, were done on the bare white canvas, one using streaks of red and yellow, in a color pattern that satisfies me.

Let’s Dance, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

That’s the fun to me of abstracts—I choose a color palette but am not quite sure where they will end up. (I confess that even after I’m done, I often add marks in pen or more paint to “finish” them.) I plan to do more abstracts, after I do a few more in my “Street Scene” series.

Blue Feather, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

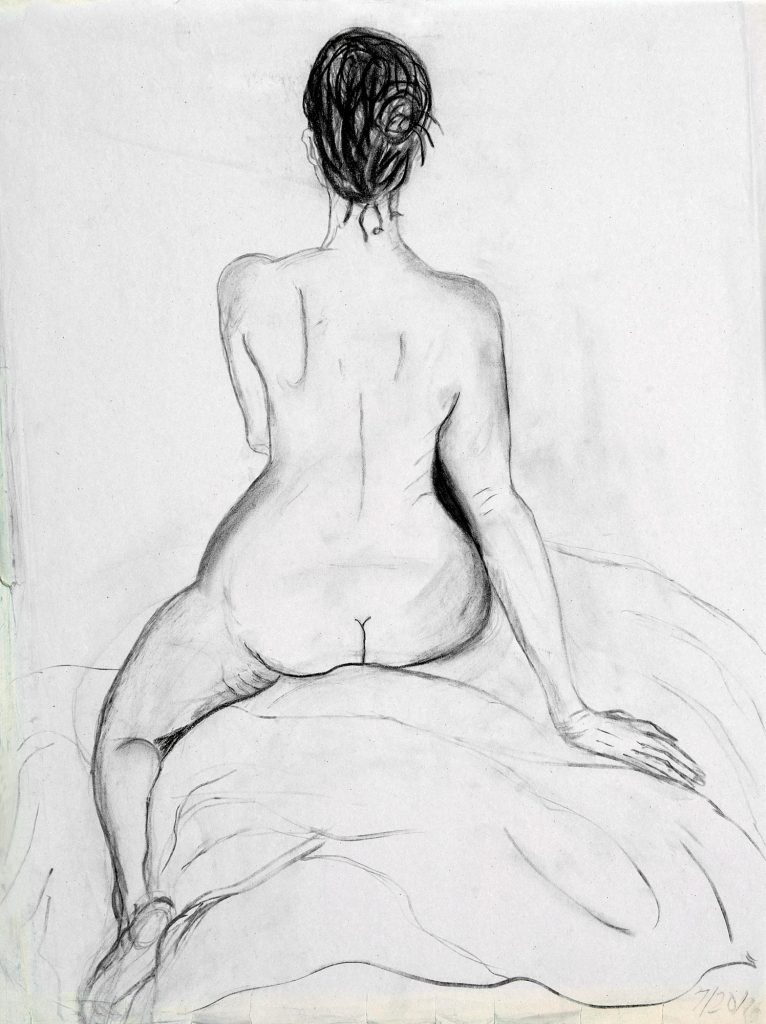

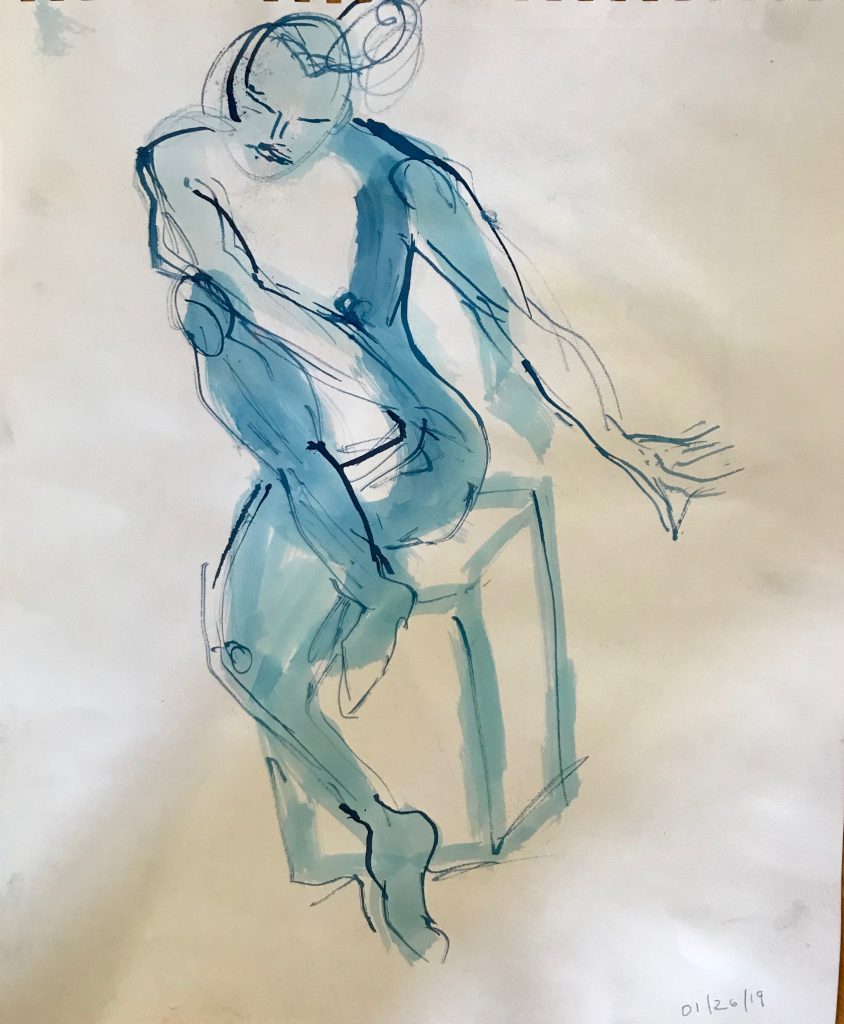

Do you go to life drawing classes regularly?

I’ve been going to life drawing classes and model drawing sessions for many years. In 2008 I was studying with Mike Kitchel, through the Pacific Art League in Palo Alto, CA. He taught a very geometric style of capturing form, which I think is a good basis for further study. Since moving to Santa Cruz in 2014, I joined the Santa Cruz Art League, and became even more dedicated to figure study with a marvelous teacher, Susie Wilson, an expert in form relationships, including explaining how to visualize an invisible grid on the body.

Marla 2, Vine Charcoal, 18”x 24”

She is extremely encouraging, and her concentration in how to really see the relationships and proportions of all the parts of a body, as well as how to capture movement and expression, was just what I needed to progress. I took her classes every week for about three years, and gradually became more confident in my abilities. I have entered and won several awards with my figure paintings which makes me happy that I’m on the right track!

Blue Move, Ink and Bleach, 18”x 24”

Discuss the female form and its beauty and shape as inspiration to you in your work.

I love to draw and paint the female form, especially as I’ve been studying figure drawing for several years. The more, curvy the form the more fun I think it is, as in my “Muriel” paintings. Another thing is that I think that women are victimized so often due to bodies that don’t fit the unrealistic advertising and celebrity examples that I want to show through my painting the beauty of all types of bodies.

Muriel 2, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

Muriel 2, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

I also enjoy the challenge of drawing poses that are more difficult, such as foreshortened ones. There is something very satisfying about getting the proportion right as well as the likeness and expression on a face. Funny thing is that I’ve developed a drawing style without trying to—folks tell me that my drawings have a definite similarity to each other.

My figure paintings are definitely inspired by Matisse’s loose yet expressive style. I love his patterns and colors too and try to incorporate this into my work as well. I did a series of figure paintings based one of my drawings, using different colors to emphasize various aspects of the form and to depict various moods and themes, including the theme of a German legend, the Lorelei, a woman who threw herself into the Rhine River for love of a man who abandoned her. (She got her revenge in the legend as she became a rock in the river which caused shipwrecks!)

Unlike my figure drawings, actually my figure paintings are in a wide range of styles. I don’t plan it exactly but find out what happens as I put paint to the canvas. Some are more expressionistic, some more realistic and some more abstract.

Waiting, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

You give week long classes comment briefly on the format they take.

The classes take place at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, (www.ghostranch.org) a place where Georgia O’Keeffe lived and worked. It’s a gorgeous area of the USA, with many colorful, unusual rock formations, a beautiful river, (the Chama River), and mountains, including the Pedernal, which O’Keeffe named as her own.

Well, now it’s mine as well (<*

I’m honored to teach a class called “Inspiring Landscapes: Paint It Your Way” (as part of the Spring Festival of the Arts; from Sunday (evening), March 22–Friday (morning), March 27, 2020.

I’ll be teaching a variety of techniques, including travel sketching using pen and watercolor, color mixing technique, and acrylic and watercolor landscape painting. A good friend and excellent travel sketch artist, Julie Barreto, may be a guest teacher on one of the days when we do a field trip in the area. This workshop is available for all levels of painters and all media. The class format include demonstrations, daily studio time to work on each person’s own projects, at least one field trip and lots of individual attention to help each person progress. Besides the opportunity to stay at this beautiful property.

Using images of your work show how you have developed through your artistic career.

I started as a child in Ohio; don’t know if that counts as part of my artistic career! I went to art classes and won a few awards including one as best in show in my age group.

Ohio Fall Forest, Tempura, Ink, 18”x 24”

Ohio Fall Forest, Tempura, Ink, 18”x 24”

After moving to CA, I went back to my art again seriously in 1998, as I was going through a divorce. I first concentrated on my drawing skills as I was quite rusty. I took classes at the College of San Mateo, San Jose State, Pacific Art League in Palo Alto, CA and from excellent private instructors.

Watercolor took over my painting life, although I’d done oils as well. (At that time, I’d never worked in acrylics.) I painted mainly still lives and flowers, found joy in using exuberant color. I started exhibiting at galleries, restaurants and art shows and was even invited to represent the United States at the Florence (Italy) International Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary Art in 2011. I also taught watercolor for various city parks and recreation departments, and also for private classes.

Golden Blossom, Watercolor, 16”x 20”

Since moving to Santa Cruz, CA in 2014, I have tried various styles and media as explained previously, and am having the best time exploring and working in all media and many subjects, from figures, landscapes/urbanscapes to abstracts.

Orange Figures, Acrylic, 16”x 20”

Travel sketching is important, how do you approach is format?

(show examples of your sketch books)

Ghost Ranch, Ink and Watercolor, 51/2”x 7” sketchbook

I have been doing travel sketching throughout my life but have been concentrating on it more in the past few years, especially as I’ve retired from a demanding career in technology marketing. Since then, I have had the opportunity to travel to many places, including Japan, Greece, Argentina, Chile, Italy and France, as well as New Mexico where I’m now teaching. I do plein air, on the spot sketching, depending on how much time I have to do it. Sometimes I’m lucky enough to get an hour or so, but mostly it’s grab a half an hour or even just a few minutes. I used to sketch mainly in pencil, but now I sketch in black ultra fine Sharpie or micro pens, as I like the effect. I’ve found that the more often I sketch the more satisfied I am with what I’ve done—probably an obvious observation (<*

Queen of the Hill—Santa Fe Botanical Garden, Ink and Watercolor, 51/2”x 7” sketchbook

Do you use photography along with sketching when you travel. How do you combine the two?

I usually try to take a photograph of whatever I’ve sketched or started to sketch so I can fill in details later as needed. I take a small travel watercolor set with me so I can add color—sometimes as I’m sketching but often after I do the sketch and from the photo.

I find that I get great pleasure from looking back at my sketches, they bring back the experience of the place much more than a photograph alone!

(Note the Diebenkorn cards I use as inspiration)

I usually try to take a photograph of whatever I’ve sketched or started to sketch so I can fill in details later as needed. I take a small travel watercolor set with me so I can add color—sometimes as I’m sketching but often after I do the sketch and from the photo.

I find that I get great pleasure from looking back at my sketches, they bring back the experience of the place much more than a photograph alone!

Contact:

Susan Brown

email: susanbrownart@gmail.com

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, January 2020

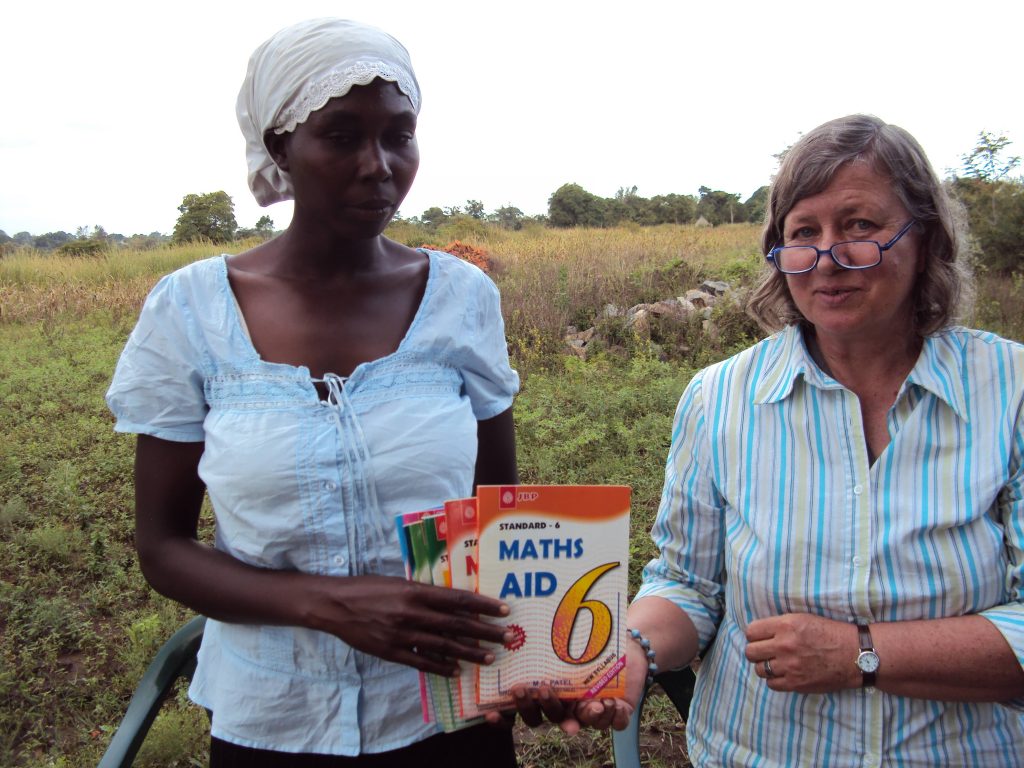

Susan Howe

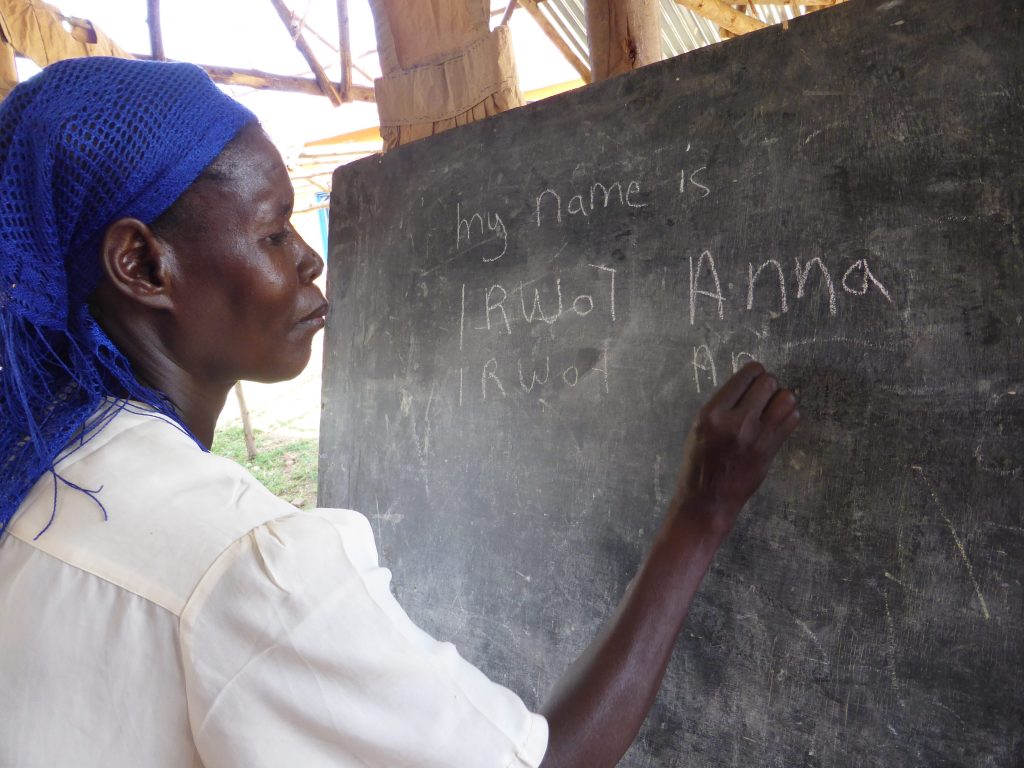

How did you first become involved with POSHU?

I first went to Africa in 2008 to live with my husband and children. Our neighbour was a doctor working in a village. He asked me to set up English class for older illiterate women who were caring for family members affected by AIDS. I found the women really appreciated the chance to learn. Then I was asked to set up these grassroots literacy classes in another 6 communities. That’s when I established POSHU. We employ local women to teach in their own language. We also distribute vegetable seed, encourage sports, and guide the women in setting up POSHU Savings Groups.

What does the word POSHU mean?

POSHU means Project of Self Help Uganda. POSHO is their staple food, like mashed potato is to us, so I wanted a simple name that reflects the grassroots nature of the project.

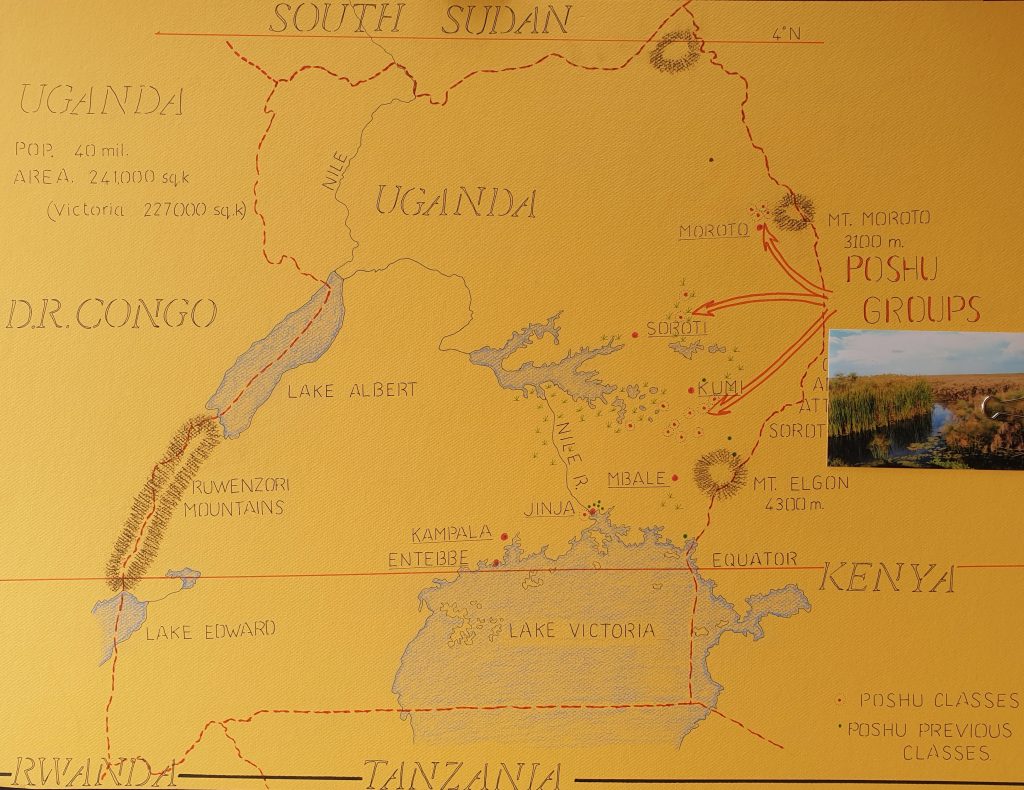

How many villages are now being helped?

In 2019 we operate in 14 rural and remote villages in north and east Uganda. Mostly we stay for 5 years, then move on. By that time the women can manage by themselves. Since 2009 POSHU Classes have taught women in 28 villages, employing over 100 part-time teachers!

How can others help with this project?

You can purchase our POSHU paper bead necklaces from Mildura’s Art Vault. Or you can buy POSHU cloth bags from LiveFast Café at Halls Gap in The Grampians.

Become a Friend of POSHU and help with fund-raising, or decide if you’d like to make a regular monthly contribution. POSHU provides Tax Receipts for donations in Australia, and you can receive our POSHU Newsletter. We really appreciate our donors who make this project possible.

Our bank details are: POSHU Aust Inc

BSB 083-764

Account 20-141-2490

Who do you specialize in these three aspects?

English

English is the national language of Uganda, yet few people in rural areas are able to speak English. If they know even basic English, it opens opportunities for them to gain employment or enrol in further study. Village leaders also attend our classes because they want to represent their people at District meetings, they tell me they need to understand documents concerning their land and water rights.

Sewing

Sewing is an income generating skill, but it’s also just a wonderful, creative activity for the hundreds of women and girls who attend our POSHU Sewing Classes. They love to meet together and work on their individual projects, whether it’s making clothes for their children, or a special dress for themselves. “We fill our space now when we walk, we hold our heads high! We know we look smart now,” they tell me. Quite something for women who have known only hardship and drudgery, who only had one dress till now. And they value the friendships they make through POSHU with women from surrounding villages.

Maths

Maths is important for women subsistence farmers when they go to sell their surplus crops. If they don’t understand how the market works, if they don’t understand basic Math, then they just accept the small amount customers decide to pay them. POSHU teaches basic Math and financial literacy. The women tell me their income has improved because of this training. The next step is helping them to set up POSHU Savings Groups, enabling the women to set up small businesses. They also use their savings to pay school fees for their children, or to buy medicine.

Can you help us put this area on a map?

Give us 3 stories that tell how important POSHU has been to these three women.

- Hellen has been our POSHU Sewing teacher in her village since 2010. She is highly respected for her commitment to her many students, and her attention to detail. Yet when we first met, she was almost destitute. The daily struggle against poverty proved too much for her husband, and he left to find work. Their three young children had only rags to wear, and there was no money for food, let alone school fees or medicine. Hellen laughed when we offered her a job as POSHU Sewing Teacher. It seemed so impossible. She had some training in tailoring, but no sewing machine. The other POSHU Teachers welcomed her, they became her friends. They saw in her what she couldn’t see in herself. Now they are a strong team. They’ve trained 200 teenage girls to sew! They also hold free classes twice a year for the women tailors who work at the Trading Centre, teaching them to sew the latest fashions and improving their skills. Hellen’s husband has returned and now they have two incomes to support their family.

- Jen has been our POSHU English teacher since she was 19 years old. She lived with her parents in their hut on the farm, so was able to save her POSHU earnings. After a year, she bought two goats which she raised up and sold. Then she bought two young bulls which she raised and sold at profit. Then she bought some land!! Every year she grows millet on her land and earns a good income! She has a plan for her future.

- Betty was almost destitute when we asked her to be a POSHU English Teacher in her village. She was overjoyed and cried. Life was difficult for her with a disability meaning she couldn’t dig in the fields. After 5 years of teaching with POSHU, she left last year to work in a shop in the town. Perfect for her!

- Our POSHU Teachers grow in confidence. Each year, some of them leave to attend full time Teacher’s College, with the support of their families and their community. Their goal is to become Primary School teachers!

Happy Teachers

Discuss the importance of women helping women.

It’s so important for women to help other women. In the village context, there is already enough knowledge between them all to find their way out of poverty. They don’t need me, or anyone else telling them what to do. What they need is the opportunity to talk and to learn from each other. Almost every village now has at least one woman who is literate. POSHU provides a box of books, pens, chalk, black board. Many of our POSHU teachers are born leaders. We pay them to work in their own village, guiding 25 women and girls towards basic literacy. We try to say “Yes” to their ideas for developing further. Women are inspired by seeing what others are achieving for themselves, and importantly, they gain strength by working together and discussing everything as a group. Everyone has a role to play.

How are the women adding to POSHU themselves?

Each village is different, facing different challenges. And yet poverty has a familiarity to them all. Small changes can make a difference, everyone’s contribution counts. POSHU is valued by the women, and by their communities because we work lightly with them, we don’t tell them what to do. They have the freedom to develop their own ideas, to experiment with what works and what doesn’t. Every woman deserves this right.

What are the plans for POSHU in 2020?

POSHU works with the whole village, because women make sure everyone is included. In 2020 we plan to conduct training for young men in basic manufacturing skills. We have land in eastern Uganda where we’re building a shed that will be our POSHU Enterprise Centre. And we’re supporting a young woman to attend Basic Computer Training and Office Management. She will be an asset to our Enterprise Centre.

Contact:

Susan Howe

Email: susan.h.howe@hotmail.com

Our bank details are: POSHU Aust Inc

BSB 083-764

Account 20-141-2490

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, December 2019

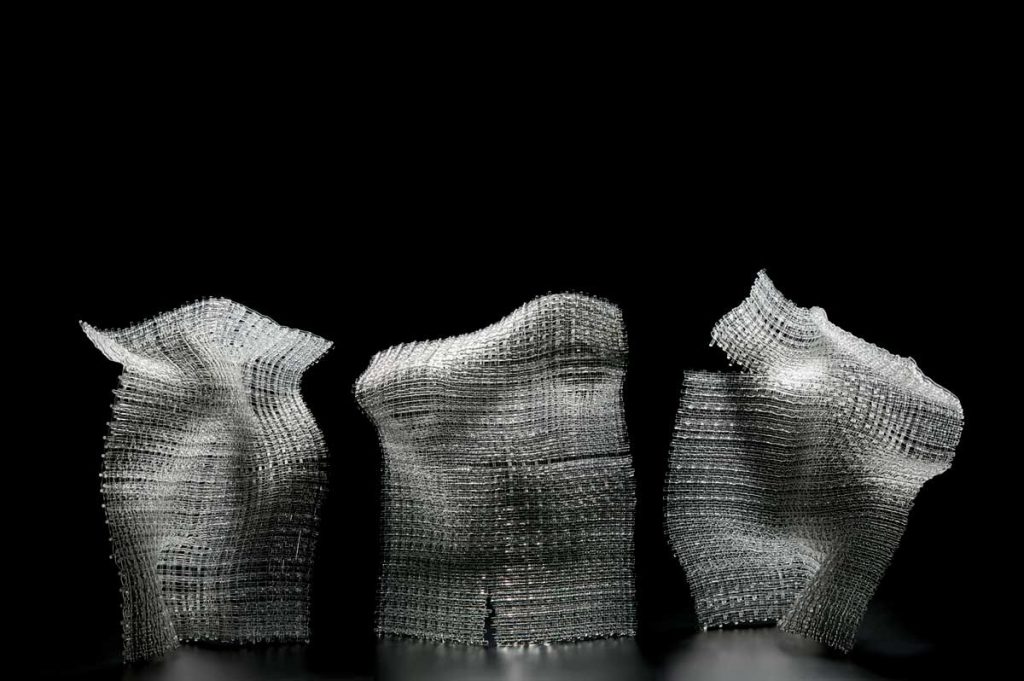

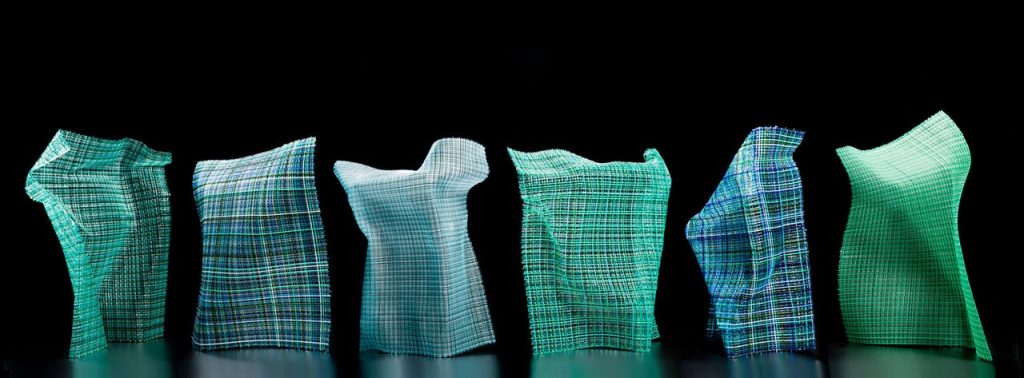

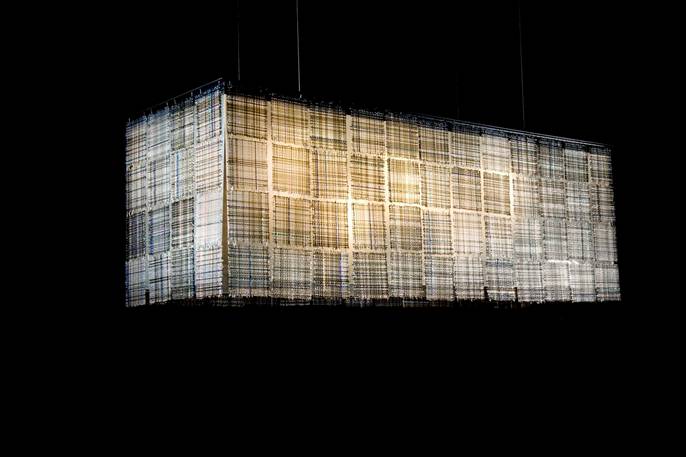

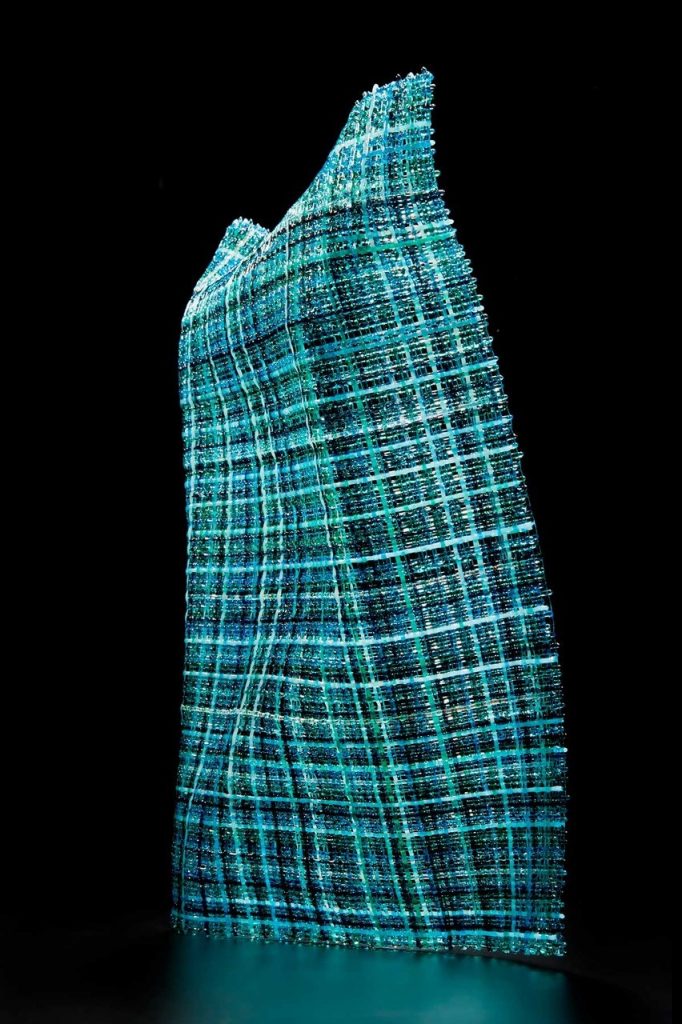

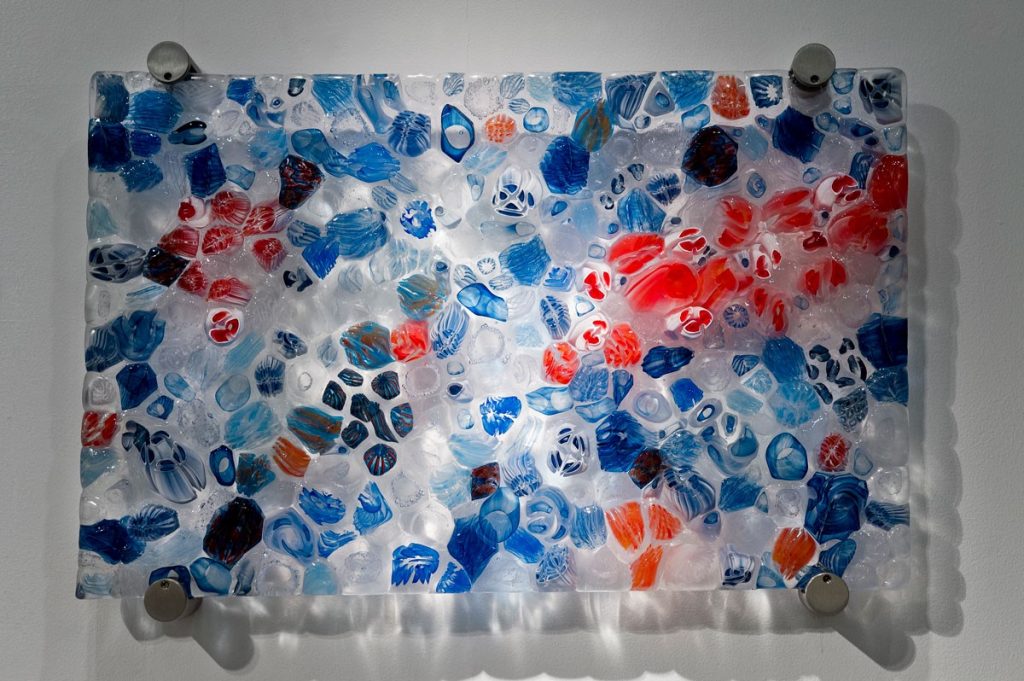

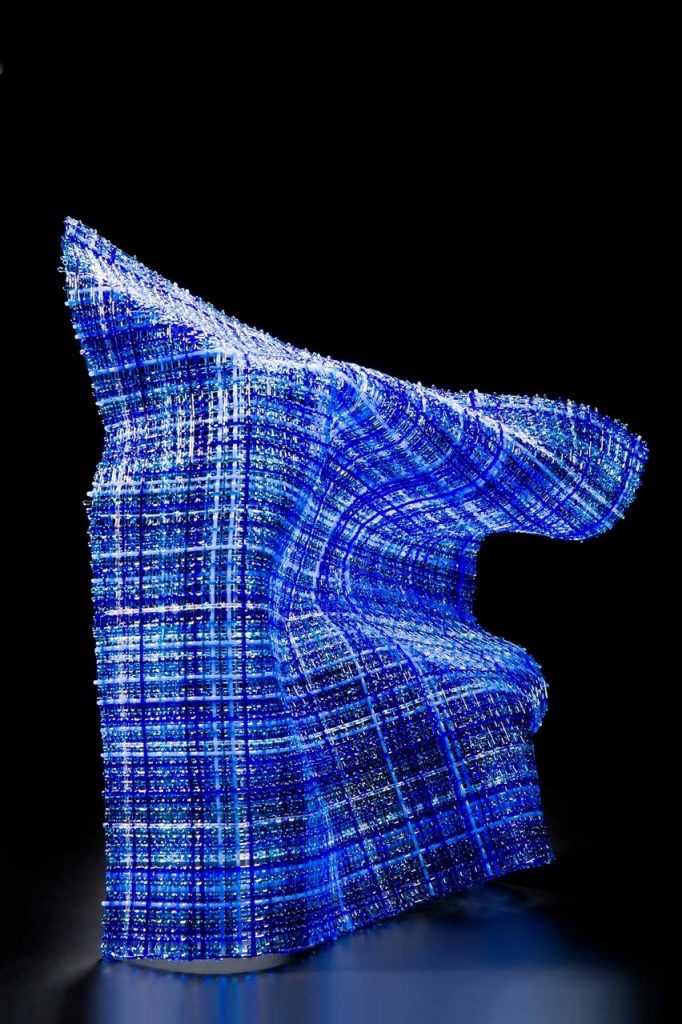

Clare Belfrage

Can you discuss your use of line and its relationship with nature?

I have worked with the repetition of an element for many years now and most often using line to create pattern and rhythm. I think initially I used line to reference the grassy spines of the Yakka or Xanthorrea plant as well as using line to create glass drawings. I see the repetition of line in many parts of the natural world whether it is in the specific patterns of plants, rocks, shells, or as an expression of current or movement as experienced in water, sand and clouds. Working with line has been the way I’ve expressed something of the complexity of life that I have observed around me in the natural world. I am really interested in the detail in nature and ways of marking out the living of a life, the passing of time.

Awash in Grey, 2014, blown glass with cane drawing, sanded, 52 x 45 x 7cm, Photo by Grant Hancock

How are the threads of glass attached and can they be felt in the final work?

The threads of glass, often called stringers, are fused onto the surface of the glass during the hot process. I prepare the stringers by stretching out a gather of glass with a coloured core to a very fine diameter. Then I use a small torch to heat the stringer at the point of contact to my glass piece to attach it while manoeuvring it to create the pattern.

For different pieces I draw at varying stages of the process and this has an impact on the tactile quality of the line. When I draw early in the process and then gather more glass over the pattern work, the surface will be completely smooth. When I draw later in the process then the line work sits in relief and can be felt.

How have Canberra and Adelaide combined in your art life?

Being part of community has always been really important to me. In fact I’m sure its one of the aspects that really drew me to glass. From the time I finished my studies I felt I was able to jump into the current of Studio glass here in Australia and overseas, and there are many ways I have benefitted from this community. Adelaide and Canberra have been particularly important to me. There are many connections between these two cities and the incredibly vibrant glass communities they house.

I have worked in and around the JamFactory Glass studio in Adelaide since the early nineties and it is still where I do my glassblowing – and also participate in monthly clean-ups and studio meetings. In 1997 I was part of a group that started blue pony, also in Adelaide, a shared studio that ran for 15 years. This was a formative time for me as an artist and again a really important period of community support and growth.

I have also felt a strong connection to Canberra since the early nineties and have enjoyed great conferences, exhibitions and other events there. From 2009 – 2013 I had the privilege of being the Creative Director of Canberra Glassworks where I was able to engage with the Canberra based community and be creative at a whole other level to my artistic practice. I worked with a strong team and we were able to present great programs and events across all areas of glass making: workshops, exhibitions, residencies, collaborations, parties and festivals with the dual engagement of artists and the general public.

I am based again in Adelaide but enjoy all of the connections between the two cities and in fact my solo exhibition, A Measure of Time, a JamFactory touring exhibition is currently on show at the Canberra Glassworks gallery.

How important has the Tom Malone Glass Prize been to your career?

Winning the Tom Malone Prize in 2005 was an absolute thrill. It is an incredible validation of your work as an artist. The prize money is always very useful and being in the public collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia is of course such an honour.

Tom Malone Prize Winner 2011, 2010, blown glass with cane drawing, 36 x 50 x 9cm, Photo by Rob Little

Winning the prize a second time in 2011 was probably even more of a surprise! The work was very different from the first piece which was great, and the judges, from their comments really acknowledged the development in my work which again was very affirming.

Take two pieces that have gone into overseas collections. (What and why these have been such highlights to you?)

Leaf Circuitry pair, (in the Corning Museum Collection USA) Tallest 42cm, Photo by Rob Little

The Corning Museum of Glass acquired two Leaf Circuitry pieces. These were some of the hardest pieces I have made in terms of the drawn pattern. The pattern comes from a type of eucalyptus leaf that I found particularly unusual. I was excited by it because of the way the rhythm was established and then interrupted by tangental lines. I was very glad that these pieces went to Corning.

With over 25 years, experience in glass art, what have been some of the major changes you have seen in the glass world?

I think the digital age has meant that there is so much more information that students can access. You can watch Youtube videos on almost anything! I think this has really increased the technical knowledge and skill levels in glass.

I feel like I have seen the popularity of glass rise and then fall again both for makers and in terms of the market. I think these things happen in cycles and that’s ok especially if you keep a long view.

What I really feel excited about is that artists are still being highly innovative with the material and that is ensuring a vitality within contemporary practice.

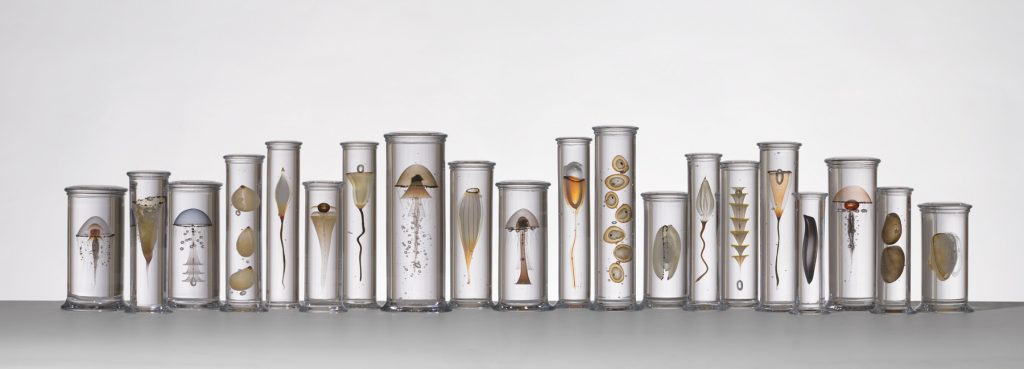

Collection of vessels at the David Roche Foundation Museum, Photo by Pippy Mount

Many of your works are all about form and shape. Discuss this aspect of your work.

A long time ago I moved away from the idea of ‘decorating a form’ and focused on the form and pattern being integral to each other. The form or shape always comes from the core idea but without heading down a path of being too literal. I like to think about what is the essence of an object or what are the core elements. This has resulted in many asymmetrical and flattened forms to carry the pattern work of my glass drawings.

Close Impression, teal and white, blown glass with cane drawing, sanded and pumice polished, 35 x 32 x 11cm, Photo by Pippy Mount.

Size, do you have a limit to the size of the work you do?

As my work is all made from the process of blowing glass there are definitely limits to the scale. In the last 12 months though, I have taken another step up in scale. I have a great team I can work with and we have been able to go pretty big for blown glass. This has enabled me to explore the feeling of a monolith and also the relationship between pattern and form on a larger scale. I guess the largest pieces are approximately 12 kilos and close to 70cm tall.

Untitled #6, Blown glass with cane drawing, 41 x 31 x 8cm, Photo by Grant Hancock

Pistachio and Blue collection is a group of pieces. Do you make many collects or mainly single pieces?

Over the last 20 years I have presented work most often as singles, but I have definitely made pairs and collections. Sometimes it is how the pieces speak to each other in a collection that becomes one of the most interesting aspects of the work. Most recently I have presented some collections made from pieces from different series. This has been particularly exciting for me.

Quiet Shifting, Purple and Gold Blown glass with cane drawing, sanded and pumice polished 64 x 40 x 20cm Photo: Pippy Mount

Comment on the title, SALA and your personal thoughts on this?

SALA – South Australian Living Artists Festival - is a brilliant, inclusive and huge visual arts festival held every August across South Australia. SALA invites all artists at all levels to participate. It is the biggest visual arts festival in Australia. In 2018 I was the ‘Feature Artist’ of the Festival. This meant that a monograph on my career and practice, titled, Rhythms of Necessity, written by Kay Lawrence and Sera Waters was published and launched. I also had a major solo exhibition, A Measure of Time, as JamFactory’s 2018 Icon, and national tour of the exhibition to eleven venues over three years. I gave a number of public presentations and demonstrations. This was an immense honour and a great opportunity to highlight glass making practice in South Australia and beyond.

How important is professional development to your current work?

I have always enjoyed being active in projects outside of my direct practice. I like the intellectual stimulation and contact with other interesting people. I’ve been involved in developing and hosting conferences and I always attend our Ausglass conferences. I am currently on the Board of Guildhouse, a not-for-profit organization that supports South Australian visual artists, craftspeople and designers to build and maintain sustainable careers. I’m not sure that these experiences directly influence my art work but they are nonetheless very important to me.

Take a resent piece and discuss…

A MEASURE OF TIME from Randy Larcombe on Vimeo.

This was made by Randy Larcombe. It is also called A Measure of Time.

How does your personal environment influence your work particularly colour?

I definitely look to the natural world for my colour sensibility. I mostly look at Australian plants but I am not a purist. I enjoy gardening and I have made a pretty nice front garden of native plants that has really focused on different textures. When I can I go bush walking and camping and I draw inspiration from these experiences.

Clare Belfrage

Adelaide, Australia

insta: clare_belfrage

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, December 2019

Emma Rodgers

Can you expand on the importance of people, places and experiences in your life as an artist?

People who have influenced me

People who have influenced me

There have been so many people who have supported or had influence on my work an amazing tutor at school Stuart Dimalow , who encouraged me to go to art school and believed in me and encouraged me from such an early age. My Mother who took me to galleries and allowed me to constantly turn our kitchen table into a studio space. Sue Tucker who when at art school help me to develop my work through constantly show me so many aspects of these processes. David Jones at university who took me out of my comfort zone and made me engage with the public and apply for everything! My husband and family who has always supported my projects, no matter how bizarre they maybe. Henry Jabbour , we bonded over our love of art and have become great friends along the way.

Henry Jabbour and Emma Rodgers

Castle Fine art foundry, my work would not have grown this way if I didn’t have the security of your technical skills. And so many others Thank you all , my path would not have been as rich and diverse without your influences.

Places and Experiences

I travel a lot and think it is my greatest luxury , to experience other countries, cultures, history and wild life has had a huge influence on my work.

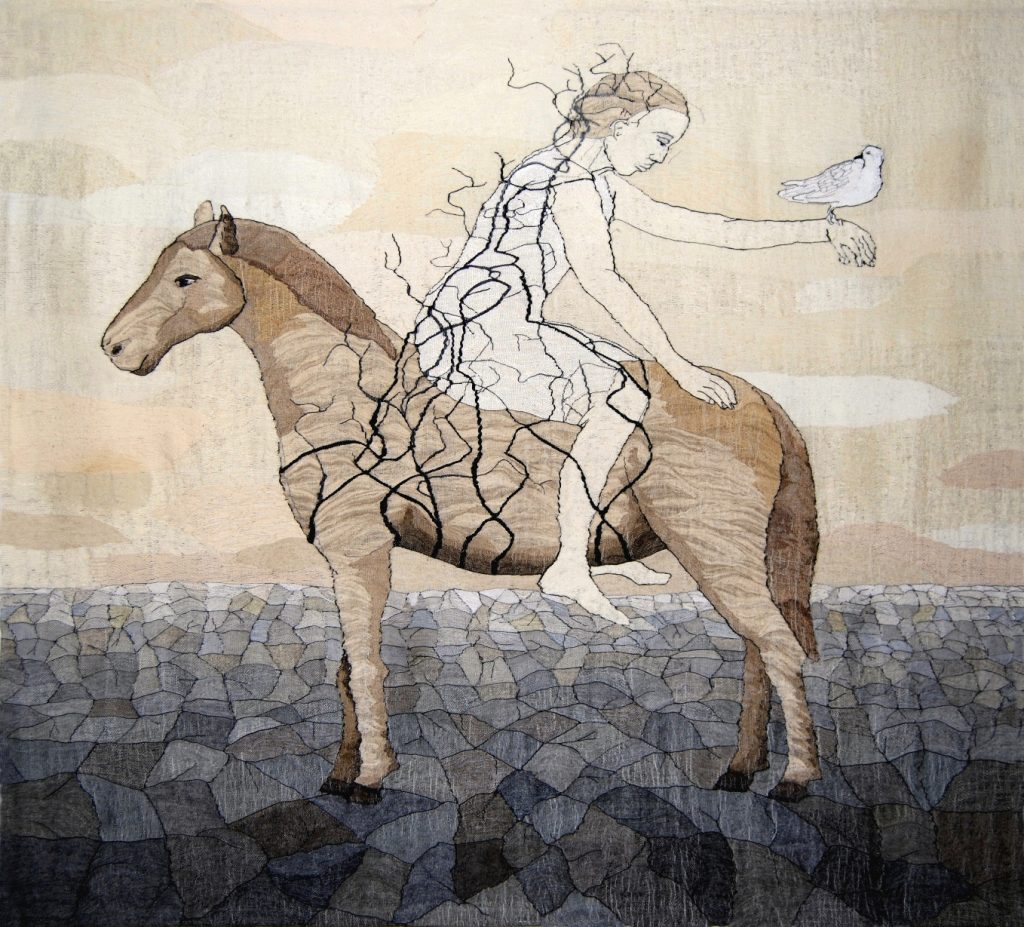

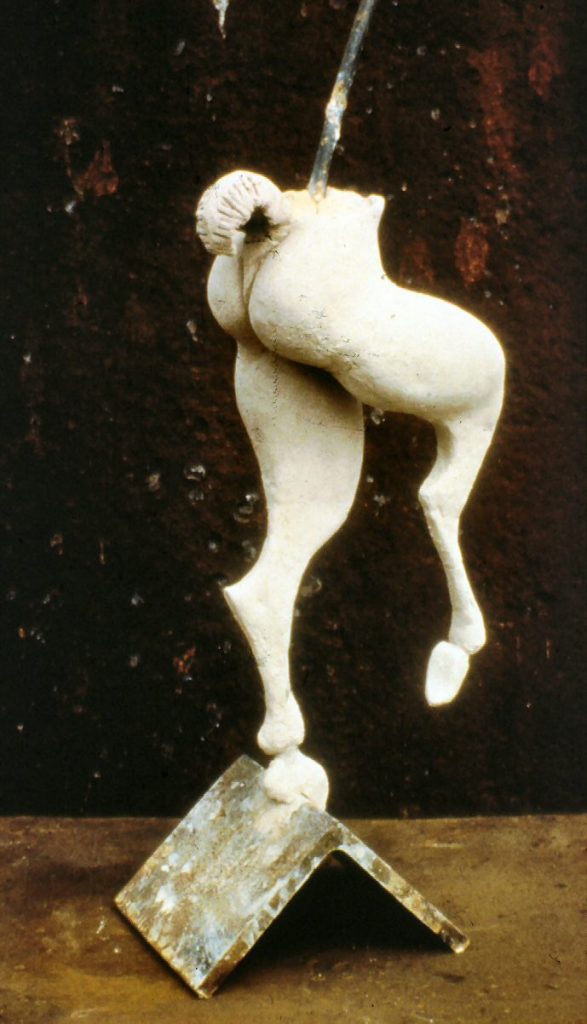

Museums. When visiting museums, I find the artifacts that are not fully restored the most interesting, allowing the viewer to fill in the gaps. Often the negative space is just as interesting as the form that remains. Some sections maybe well preserved while other extremely eroded and when they are reintroduced to sit next to each other after the passage of time, the contrasts are quite beautiful.

There is a piece in the British Museum of a horse and rider. All that remains is the horses head and torso with the rider’s hand tenderly placed on its neck, it shows such intimacy that for me, if it was ever fully restored it would destroy the piece. Nature is incredible in all its raw, yet intricate beauty. The more you peel away the more you find and Clay with its earthy characteristics is the perfect medium to translate natural form.

Museums and medical books are the perfect inspiration for working out how to display a piece. From the simplicity of the stands through to quite complexed forms when the artifact needs more support, some of these structures almost become part of the form, enhancing it, but without being too intrusive.

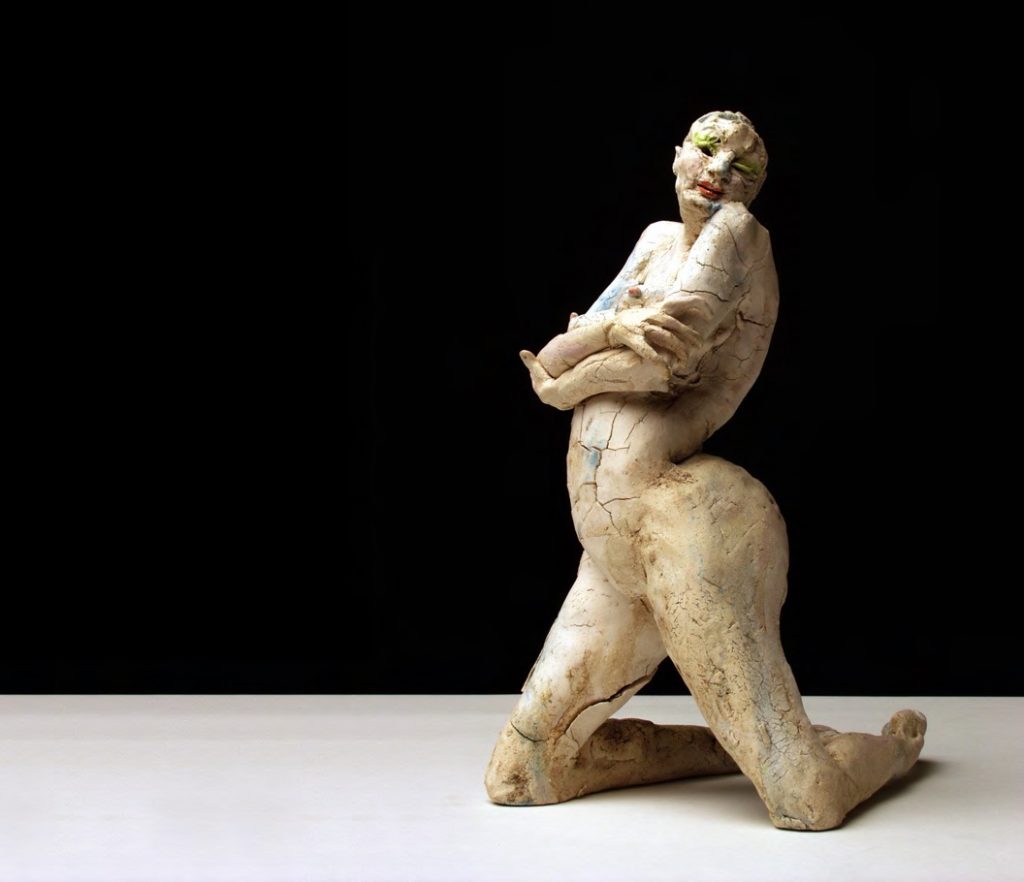

Reconstructed Figures

When considering displaying my work I look at what each piece needs. Some require the elevation of a stand to give them more presence and allow the viewer to see all angles. Whereas other for example the mother and child monkey, I want to appear to have climbed up into the show and are taking a rest. To achieve these holes are inserted at the correct angels and size in construction stage and stone is chosen by which best colour and surface finish suits the piece.

You mention two places Veterinary Theatres and Marvels space ships as important places in your career. Can you give a brief synopsis of each and their involvement in your art practice.

Through giving talks and demonstrations At Leahurst Veterinary school about how much nature inspires me. I was invited to view the facilities which were fascinating, as they are often striving to develop and improve methods within the practice with state of the art technology and a dedicated team. It is a privilege to have access to their daily life, from sketching in a field through to watching an autopsy and seeing how beautifully nature is constructed.

Marvel

Marvel

Marvel

I was approached by Marvel Films to create work for a Film called Guardians of the Galaxy. The pieces needed to feel other worldly as they were to be placed in the Collectors spaceship. This is a character that travel around the galaxy collecting artifacts. I loved working on this and seeing how the sets were made was amazing, such attention to detail. They even made space sweets!

Bull

Marvel featured this sculpture in the Stark Towers penthouse of the character Iron Man, played by Robert Downey Jr, Avengers Age of Ultron.

I was then invited back to designing and producing sculptures with Marvel films for the sets of Avengers Age of Ultron. My children were invited on set and met Robbie Downey Jr and Chris Helmsworth whilst seeing a whole new perspective of what goes into a film. Wonderful memories for them.

Mother and Child

If you are willing to explore various routes of art, one of the huge perks of this job is being able to venture into other worlds.

Owl

One of my friends has a pet owl, so I often visit to sketch, photograph generally observe. The sketches range from close fine detail to very loose often charcoal drawing whilst they are moving, jotting down just a few marks will give me the essence of what I am aiming to capture.

Being able to handle her and feel her joints really helps me to understand how she moves. When I feel I have enough to work from I will arrange everything around me in the studio and start to construct small quick studies in clay and wax, not really a maquette, more of a 3d sketch. I will then develop one of those poses either in wax or clay. With Luna, I wanted her wings to be made from her environment , but not necessarily include feathers as I felt that to obvious. I gathered bark, branches, moss and shard of slate and working from them developed her wings. Once I was happy with the form it was moulded, and a wax was made from this of which I hand cut and was then cast in bronze. I patinate all my own work, so the pallet was again inspired by the environment with very loose brush marks on the wings to emphases movement, and more refined marks to define the face and expression of the bird. The piece is then sealed and wax.

In this work you have a limited edition of 9. Can you say where they have all flown to?

Some have stayed in the UK, others have travelled to New York, Singapore and even Beirut.

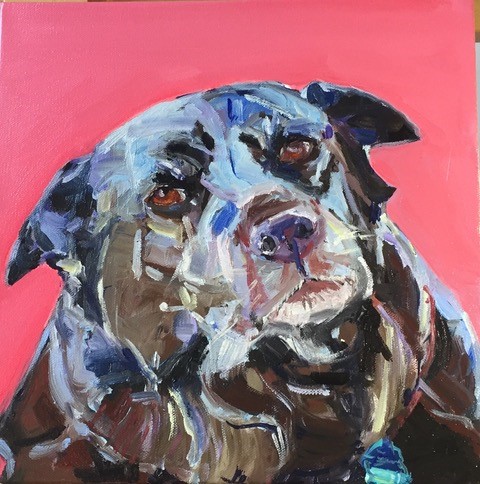

Who is Lucy? Discuss this bronze.

Lucy was originally commissioned by a client in N.Y. She has a dachshund named Lucy which is very social and can often be found perched on her back legs to be fully involved with conversation. It pose is what inspired the composition of the piece. The clients has commissioned artists from all over the world to make Lucy in their own style and is planning an exhibition of these.

Way back in 1996 you were the winner of the prestigious Victorian and Albert Museum Prize.

How did this come to be?

I was a student at Wolverhampton University and the tutors would we were regularly encouraged to apply for various exhibition and projects, to help take the fear away from filling out form and encouraging us to start to plan and how we would develop out careers. Luckily one of those forms was the V& A ceramic contemporary. I was accepted and won two prizes, which astonished me.

Rabbit 1 Ceramic, Contemporary prize winner Victoria and Albert Museum, 1996

How did this propel you into the art world?

One of the prizes was an exhibition, and with the exposure the show gave me other galleries approached me to work with them. I realised that these opportunities don’t come along very often and acted on this. It was an incredible springboard for my career. Through the exhibitions I saved and had my first bronze cast. And was luck enough to be accepted at the R.A. Summer show. With the sale from this exhibition I was able to buy a kiln which gave me so much more freedom to work and develop.

Rabbit 1 Bronze Royal Academy of Arts

Another award more resent has been your nomination to Liverpool’s ‘Top 25 most influential Women in Liverpool’ discuss this honour.

I was awarded Woman of The Year for Arts and Culture Liverpool and I think I was number seven in most influence women in Liverpool . I have also recently been awarded Gold and Platinum awards for arts and culture Wirral Life. These all feel slightly surreal, but were presented due to the attention from the public art I have produced and my work with charities using my art.

I am a patron of Clatterbridge Cancer Centre of which I works closely with in various areas. In the last year my work has raised £100,000 for The Michael Josephson Ball of which I have been involved with for a number of years. I also support a range of other charities in the North West including, St Johns Hospice, Claire House and Variety to name just a few.

This leads us to two sculptures in Liverpool, Cilla Black and Liver Bird, discuss both.

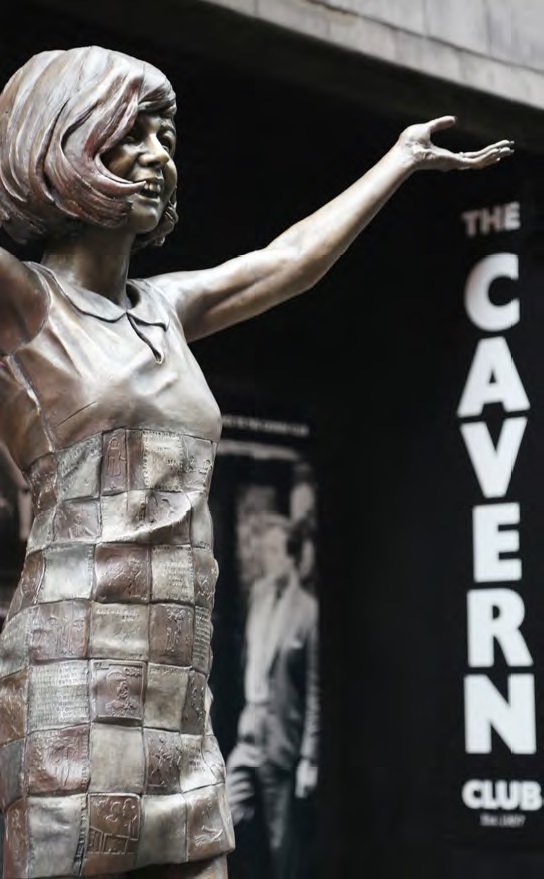

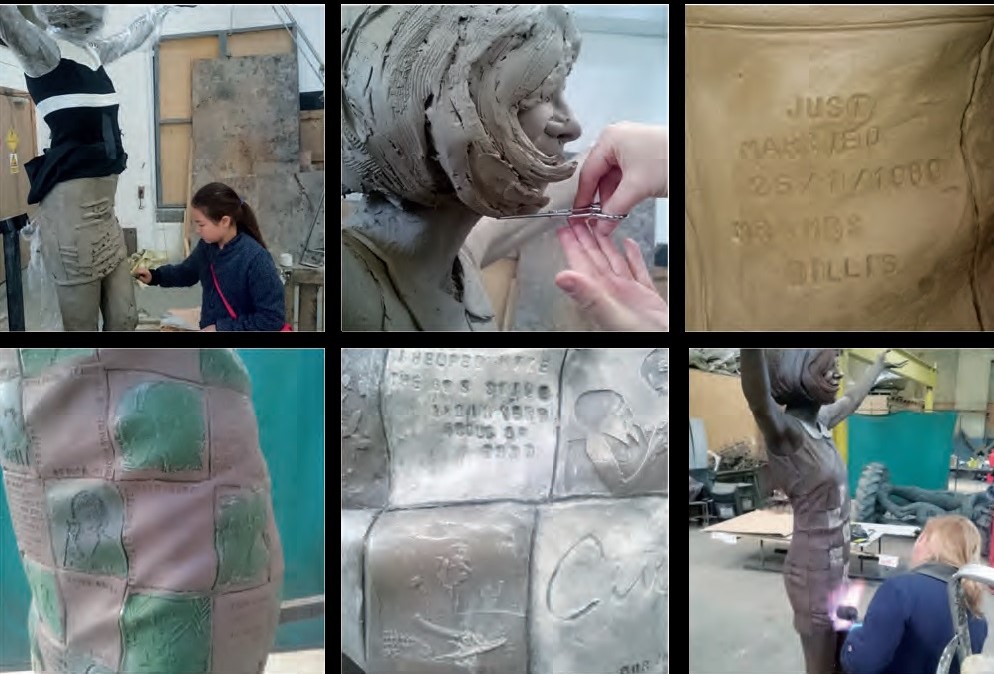

In 2017 I was commissioned by the family of Cilla Black to create a public art sculpture of "Cilla" which is now a permanent feature outside the famous Cavern Club, Liverpool.

Cilla Black

In 2017 Rodgers was commissioned by the family of Cilla Black to created a public art sculpture of "Cilla" which is now a permanent feature outside the famous Cavern Club. Cilla had worked in the cavern at the beginning of her career, so we felt it was only fitting for her to return.

Cilla Black, detail

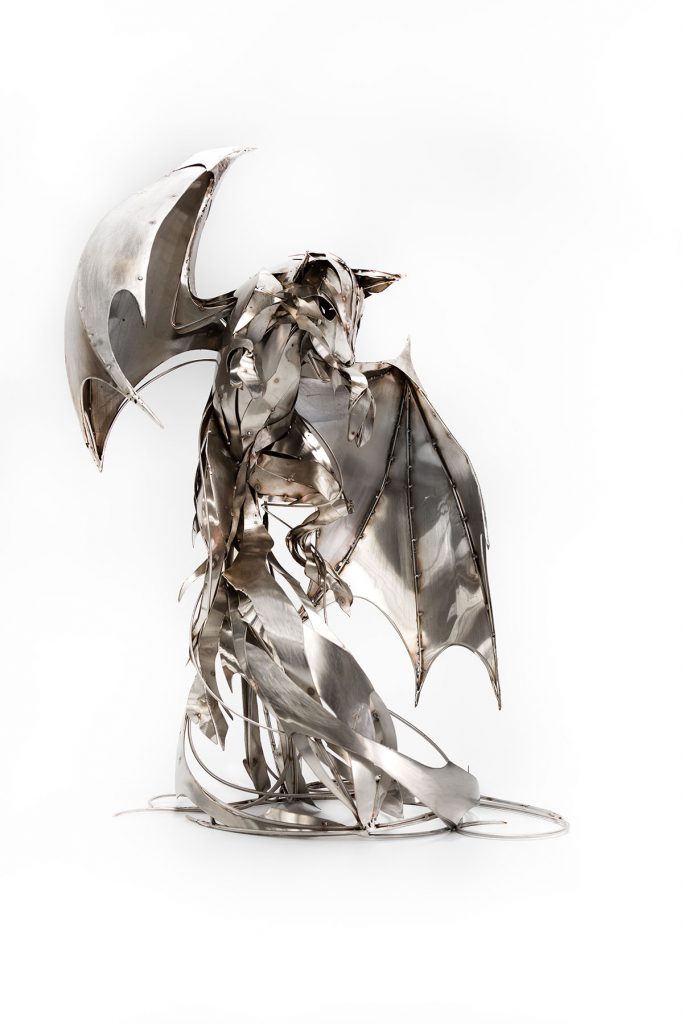

In the same year I also designed and created the world’s largest Liver bird, standing at 11 metres high.

Liver bird

Large sheet of steel is cut to appear to be constructed out of Meccano as this is the site of the original Meccano factory.

Liver bird

Liverpool in the same year she has also designed and created the worlds largest Live bird, standing at 11 metres high.

Discuss the pros and cons on working as a sculptor of contemporary celebrities who we all recognize instantly.

With Cilla Black, her family wanted 1960’s face with 1970’s nose. So that face had never existed at that time. This was created by layering images of both decades and working from them.

Cilla Black, detail

Friends of similar frames were approached and asked to pose in freezing studios whist we measured and sketched from them.

We also worked closely with the family , they would pop in throughout the process and offer advice or extra images. Robert her son provided us with a … of the first time Cilla had her hair cut by Vidal Sassoon. This was invaluable, as it showed the cut from all angels , but also how exited she was at it was around the time her career took off.

Discuss the pros and cons on working as a sculptor of contemporary celebrities who we all recognize instantly.

With Cilla Black, her family wanted 1960’s face with 1970’s nose. So that face had never existed at that time. This was created by layering images of both decades and working from them.

Cilla Black

Friends of similar frames were approached and asked to pose in freezing studios whist we measured and sketched from them.

We also worked closely with the family , they would pop in throughout the process and offer advice or extra images. Robert her son provided us with a … of the first time Cilla had her hair cut by Vidal Sassoon. This was invaluable, as it showed the cut from all angels , but also how exited she was at it was around the time her career took off. I asked a hairdresser friend Alan if he would come to the studio with his scissor , and modelled clay as he explained how the hair would move and which angle to cut, to keep it looking as natural as possible. She had such a huge career that spanned decades I chose to hide details within the dress, but I didn’t think there would ever have been enough squares on her dress to tell the full story.

Cilla Black, detail

Cilla Black, detail

Thankfully on the unveiling she was greeted well by the public, but my main thought when creating her was that I was making a sculpture for a family of their beloved mother and if they were happy , then we had done our job.

I asked a hairdresser friend, Alan if he would come to the studio with his scissors , and modelled clay as he explained how the hair would move and which angle to cut, to keep it looking as natural as possible.

Cilla Black, detail

Cilla Black, detail

She had such a huge career that spanned decades I chose to hide details within the dress, but I dint think there would ever have been enough squares on her dress to tell the full story.

Discuss the pros and cons on working as a sculptor of contemporary celebrities who we all recognize instantly.

With Cilla Black, her family wanted 1960’s face with 1970’s nose. So that face had never existed at that time. This was created by layering images of