Michele D'Avenia

What was the point in time when you knew that you wanted to be an artist?

Ever since I was a child, I have always been attracted to drawing. I continuously drew and coloured, trying to reproduce everything I saw, especially the images and covers of the "Micky Mouse" magazines that I grew up reading. Although I had this confirmation as a teenager, it seems incredible but one day after leaving school while I was returning home, feeling stressed thinking about my uncertain future, I heard a voice in my head repeating to me "you are an artist, you are an artist, you are an artist.”

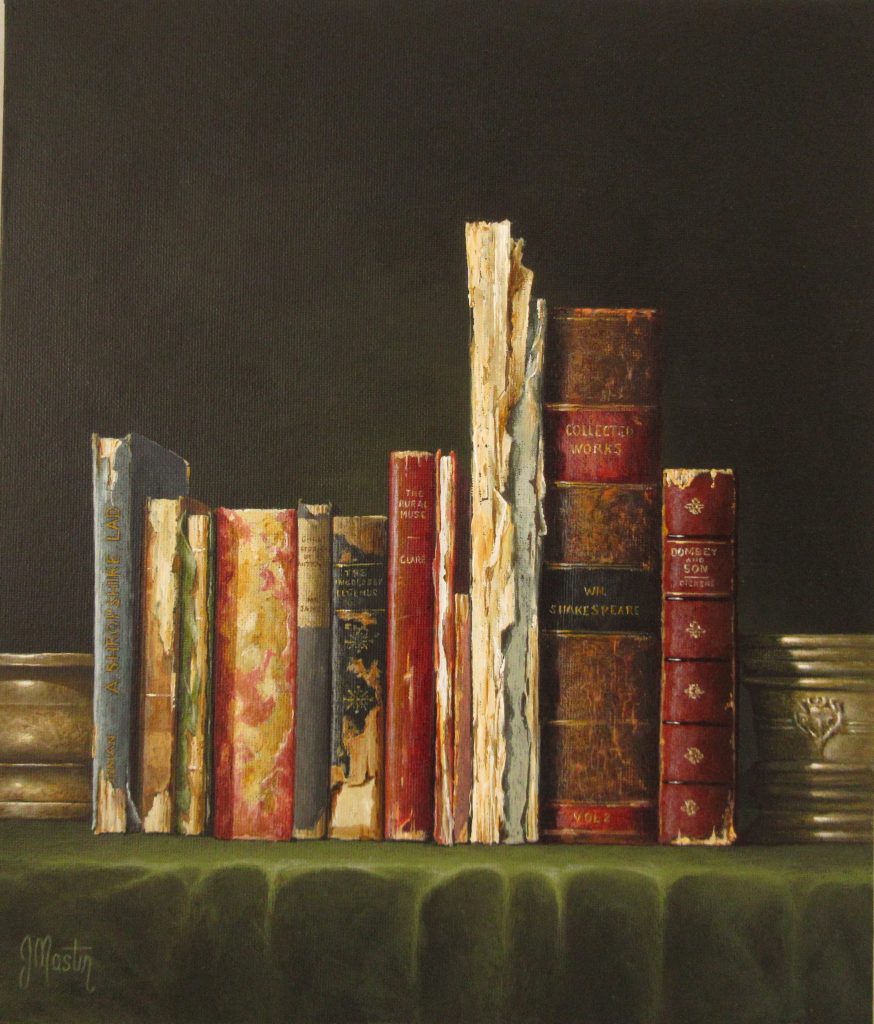

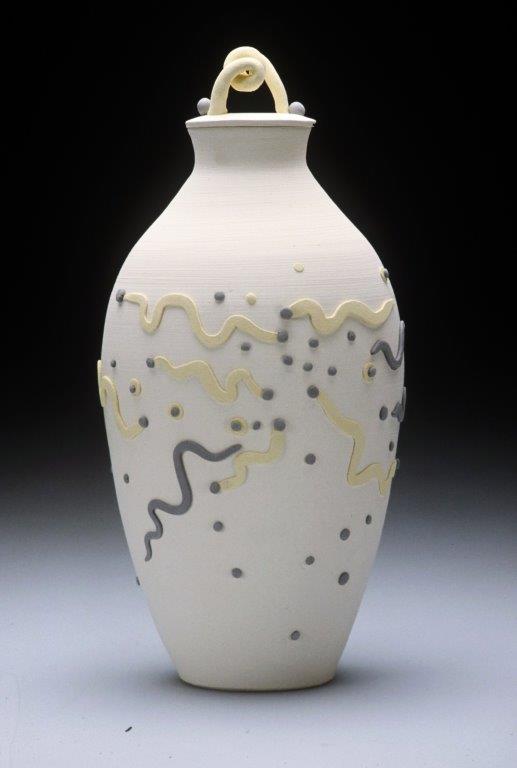

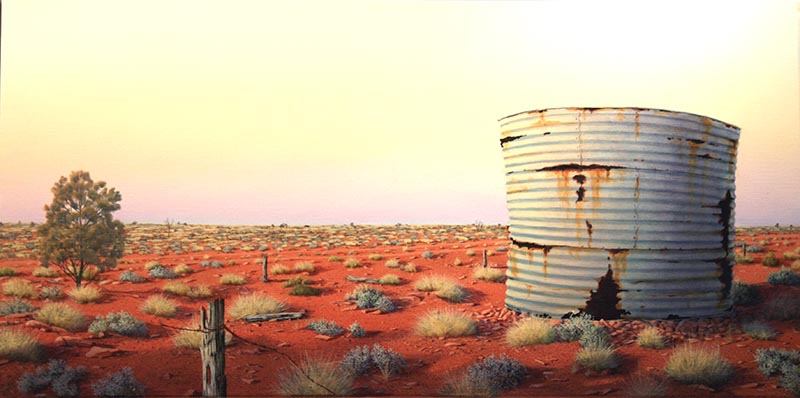

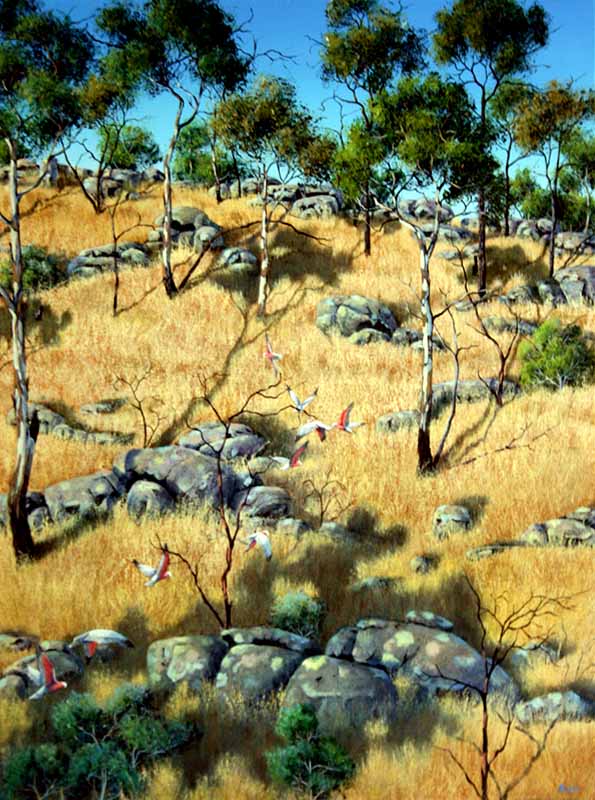

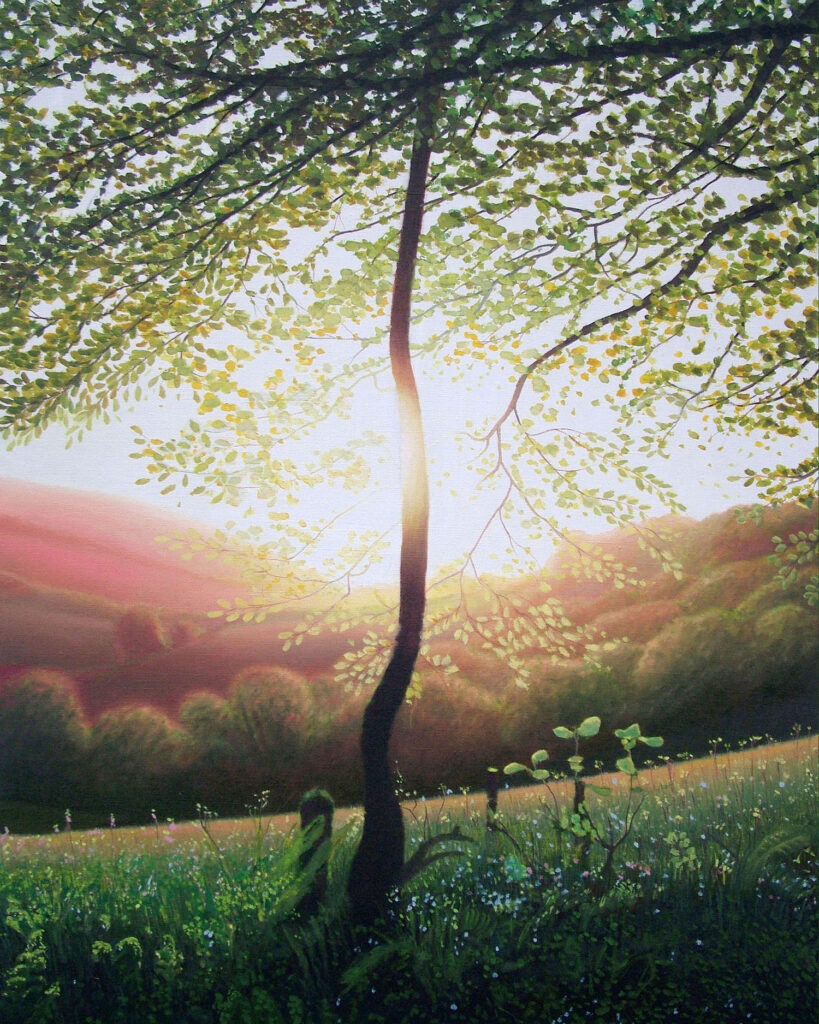

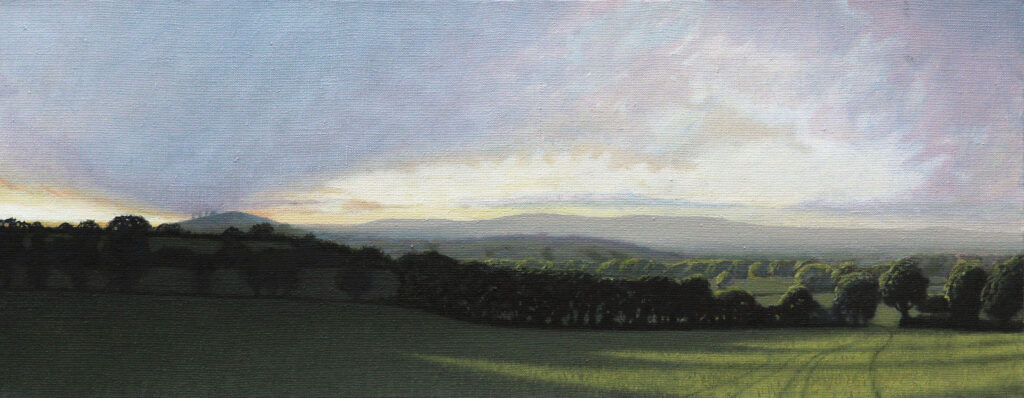

As the Sun Fades 50 x 70 cms , Oil on canvas

As the Sun Fades 50 x 70 cms , Oil on canvas

Who are two people who have helped you to achieve this goal?

My father., Painter, decorator and art enthusiast, he introduced me to the wonderful world of colour and drawing since I was a child, giving me the first lessons on drawing and colour techniques. But all this didn't help me achieve a goal, it was just a way to do what I felt and be myself.

Subsequently, in the path of my life, I have always been very lucky to surround myself with people who have always seen and believed in my talent, stimulating and making me notice that what was normal for me was actually special.

Take ‘Abundance’ and discuss the importance of light and colour in this work.

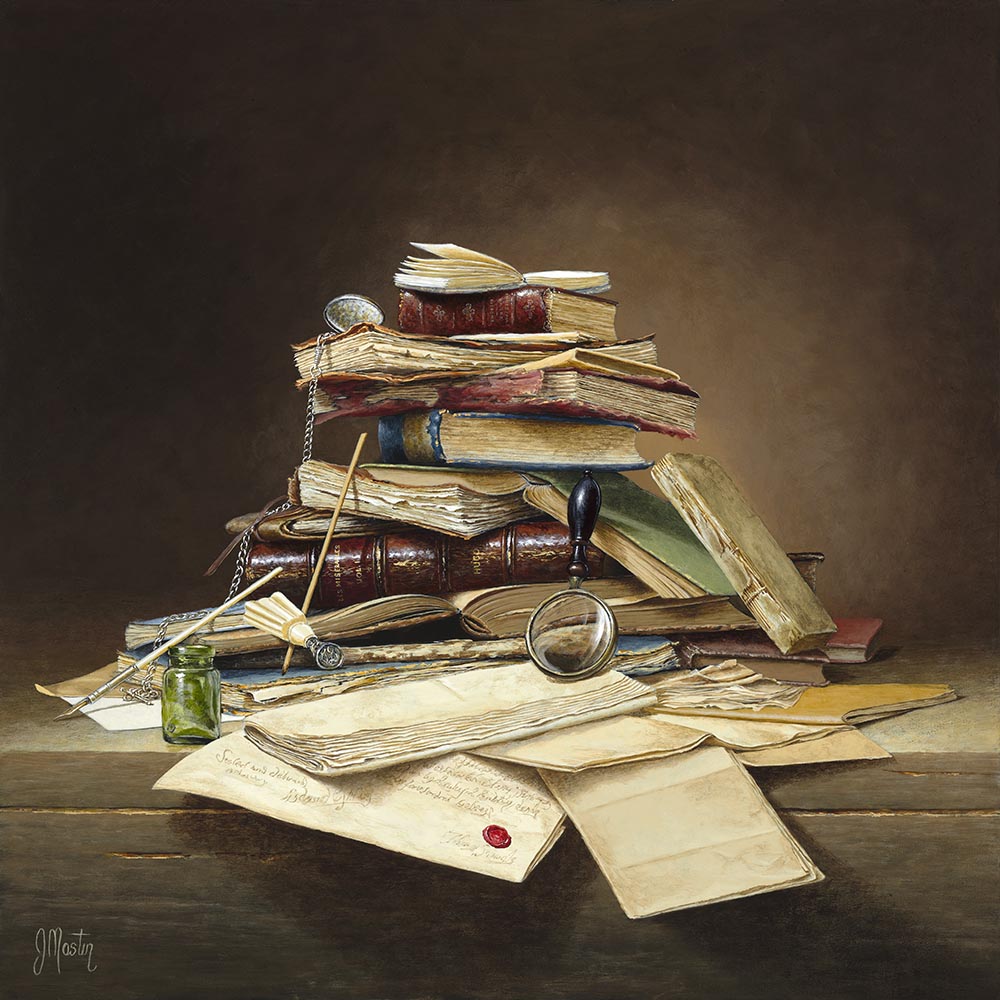

Abundance, 40 x 50 cms, Oil on canvas

"Abundance" is a medium sized oil on canvas still life painting. It is a painting of great emotional impact which manages to attract the attention of the observer. All this is not occasional, but strongly desired. The painting, with a pyramidal composition, was executed on a canvas prepared with a dark background primer (ivory black). This made it easier for me to carry out a highly contrasted work, creating a wonderful contrast between light and shadow which gives the work a great perspective. The colour, applied in glazes until saturation, enhances the objects represented at maximum chromatic power. They are rich in delicate nuances and at the same time with a three-dimensional plasticity that makes the composition emerge from the darkness, giving great atmosphere and depth to the painting.

Tell us a bit about your restoration work?

It all started when I was in the academy of fine arts. I had a great desire to learn but the academy I attended didn't give me what I was looking for. I wanted to know more, I wanted to understand and learn ancient painting techniques. One day I had a great intuition: "I would like to see how ancient paintings are made and structured" In a city not far from Messina I found a restorer who gave me the opportunity to attend his laboratory for the restoration of ancient paintings and sculptures. Shortly thereafter he took me in to work in his shop. This was a great training experience for me, acquiring all those workshop techniques and secrets, which are still part of my professional background today. Oil painting as it was done in ancient times, preparing the supports with the right plaster and painting with glazes until the desired effect is achieved. Since that moment I have never abandoned the wonderful world of restoration which continues to keep me linked between the past and present. Ancient technique representation of today - contemporary.

Comment on the way your still life work is often avoided of anything but the single object.

In the composition of my paintings, nothing is given to chance, each object is placed in the right place, in a so-called "invisible scaffolding" to create an elegant and harmonious compositional balance. Subsequently, to bring out the composition as much as possible and have an immediate reading of the painting, I concentrate as much as possible on the objects in the foreground, synthesizing the background a lot. In this way the background creates the wonderful atmosphere that envelops the entire painting. The synthesis of the background is so exaggerated that it makes the work atemporal.

In Full Bloom, 100 x 90cm, Oil on canvas

Compared to this, you also do still life paintings with many objects discuss.

The objects that I include in the compositions are always well studied, both for the shapes and for the chromatic aspect they must have. Furthermore, they have a very specific task, they are there, not to demonstrate their beauty but to symbolize or renew the plot of a story. Like in a still image from a film, where there is a before and an after.

Primi Luci 40 x 60 cms, Oil on canvas

Primi Luci 40 x 60 cms, Oil on canvas

What historical artists do you hold in high esteem and why?

As I have already mentioned, I have always been fascinated and in love with all the art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with all its immense artists who contributed to making the history of art. Although among all these artists there is one in particular who has been a constant point of reference for me and that is Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio. He is an artist with a powerful and direct language. With his strongly marked ‘chiaroscuro’ he manages to give importance to subjects and human figures, making them three-dimensional, creating a completely new spatiality. But what is even more fascinating is that the technique of this sixteenth-century master is modern and contemporary even today.

On the Edge 100 cms. Oil on canvas

On the Edge 100 cms. Oil on canvas

‘Zucchini Flowers’ you are using your humor and stretching the viewer as to is it not usually cut as a flower for a vase.

Yes, it's true, in "Zucchini Flowers" there is a bit of irony that distances you from the usual conventional representations.

Fiori di Zucca, 50 x 40 cms, Oil on canvas

But there is also a great point of truth... my own perspective. I’m driven by the constant and exasperated search for beauty and aware that beauty is everywhere. As in this case, where a simple and poor object still has great objective beauty, it's all about knowing how to grasp it.

Discuss the positioning of your model in ‘Summer Bliss’

"Summer bliss" has a rigorously balanced composition, where the female figure, with a soft and seductive chromatism, is immersed in a sparkling setting of clear and transparent water, aiming to evoke a moment of pure relaxation.

Summer Bliss, 100 x 100 cms, Oil on canvas

Summer Bliss, 100 x 100 cms, Oil on canvas

The nice thing is that in a discreet and non-intrusive way, I am present in the scene. At the bottom right you can see my shadow immortalizing the scene.

Tell us why ‘Art of the Goat’ was painted and given this title?

“The Art of the G.O.A.T” was a commission.

Art of the G.O.A.T 100 x 300 cms, Oil on Canvas

Art of the G.O.A.T 100 x 300 cms, Oil on Canvas

The client asked me to create a large painting depicting our nations favourite sport, football. As a non-fan and non-enthusiast, I really didn't know where to start. Through the many researches I did I was struck by the action of this footballer, Cristiano Ronaldo known as "The Greatest of all time" I decided that I wanted to create a painting that immortalized him with a new Caravaggesque painting depicting the image of him emerging from the darkness while performing the spectacular bicycle kick. By painting him with a strong plasticity I wanted to highlight the athlete's fantastic performance.

You give, a lot of thought, to all your titles, discuss.

I believe that the title of a painting has great importance, because it helps the viewer to understand better or faster what you want to tell them. Usually the title comes first, when I have the inspiration of what I want to create. A few, rare times when the work is finished. In that case it is the painting itself that suggests the title to me.

If this is not enough, you also sculpt. Discuss the techniques used in ‘The Ballet Shoes’ in the casting process.

Yes, sculptures have always fascinated me and are truly fantastic. It is a different language that is closer to real than paintings, because while a painting is a deception of the eye because it creates three-dimensionality on a superfine flat two-dimensional.

L’altra Faccia del Peccato, Bronze

L’altra Faccia del Peccato, Bronze

The sculpture is real, wonderfully three-dimensional, you can see and touch it from every side. Furthermore, it is exciting to give the sensation of softness to a hard material, such as marble, stone, bronze.

“The Ballet Shoes” is a sculpture that had a fairly long process.

Le Scarpette, Bronze

The initial plan was to make it in Carrara marble, but during the final phase a blow from the chisel was fatal, bang! and the marble broke. In order not to lose the work, I glued the sculpture and made a silicone mould to reproduce it in plaster and be able to continue the work. When the model was finished, I produced the bronze casting with the subsequent patina (the thin film on the bronze of the sculpture).

What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on some painting commissions that depict still life works with dark backgrounds with objects emerging from the darkness, placed in precarious situations with a strong emotional impact. When I have completed these works, my commitment is to dedicate myself to new production for the American market which has ‘water’ as its main theme.

Does your environment give you inspiration and do you want to transport the viewer?

Yes, I am lucky enough to live in a wonderful place full of stimulation and inspiration for my work.

The Fruit of Life, 100 x 150 cms, Oil on canvas

Although I believe the important thing is not the place you are in but on the contrary, the more you travel, the more you know and experience new places and things and the more you are stimulated because your predisposition to inspiration is within you. But the ability to see beauty is fundamental and is the exciting part of things. I am like a sponge, I absorb everything around me. I assimilate every emotion, I hold it and I try to pour it into my works both paintings and sculptures.

Discuss light and shadows in both your paintings and sculpture.

As you now know, since I was a child I have been fascinated by Caravaggio's revolutionary way of painting. I immediately understood the great importance of light in both painting and sculpture, so that it became the essential characteristic in my art. As in sculpture it enhances the all-round plasticity, also in paint things and people emerge from the darkness, thanks to a revealing light that falls only on the parts I prefer, enhancing their beauty and plasticity. The shadows are shrouded in darkness, taking away from the viewer everything that I don't think is appropriate.

Waiting for Freedom, 129 x 94.5 cms, Oil on canvas

It is a strong and delicate balancing act at the same time.

All this gives the work I create a fascinating perspective and the possibility of leading the viewer to the emotions I wish to communicate.

Moments, 90 x 50 cms, Oil on canvas

Contact:

Michele D’Avenia

Michele D’Avenia Art Gallery

Email: micheledavenia@hotmail.com

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, July 2024

Images on these pages are all rights reserved by Michele D'Avenia

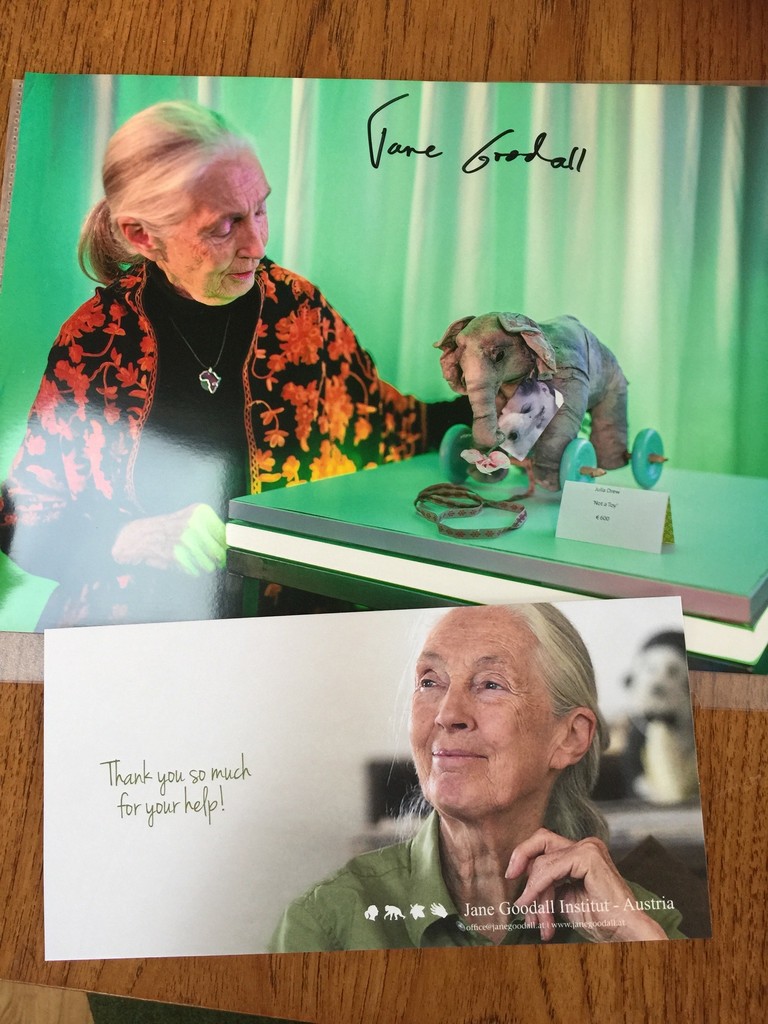

Lauren Betty

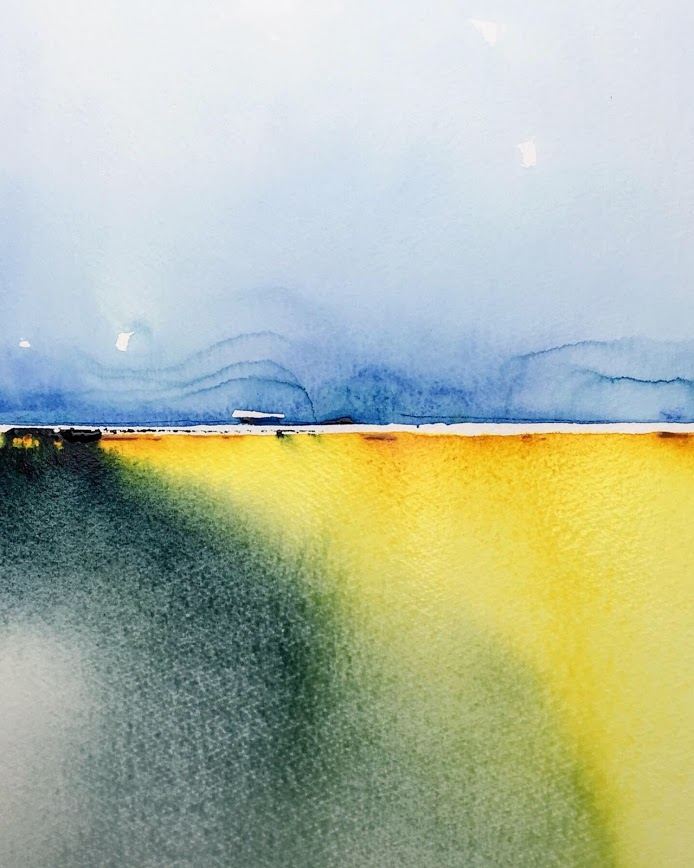

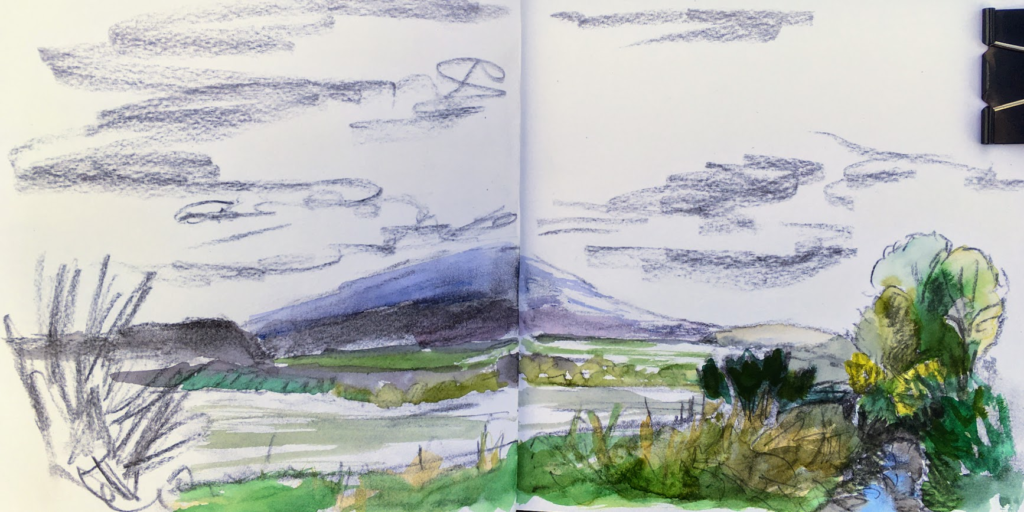

Can you expand on your comment, “…there is a rhythm that exists on the farm” how does this rhythm influence your art?

When my husband and I came across this land, there was an unfinished barn with a slight structure on top of it, a long gravel drive up to a clearing , and views of the sunrise over acres and acres of pasture. The trees were swaying and “talking”, rubbing up against one another. Immediately we knew had found our homestead and named it “Talking Tree Farm”.

Frida and Diego the goats

Frida and Diego the goats

The rhythm exists in the sound of the trees, the winds, and the seasons. I am on mother earths time, the sunrise, the sunset, and the weather dictates everything. The animals go out at sunrise and away at sunset, the rhythm is the movement of the farm and all its beings.

The influence rhythm has on my art is that is all interconnected. I moved to the farm in 2020 from the city, and my art was transformed.

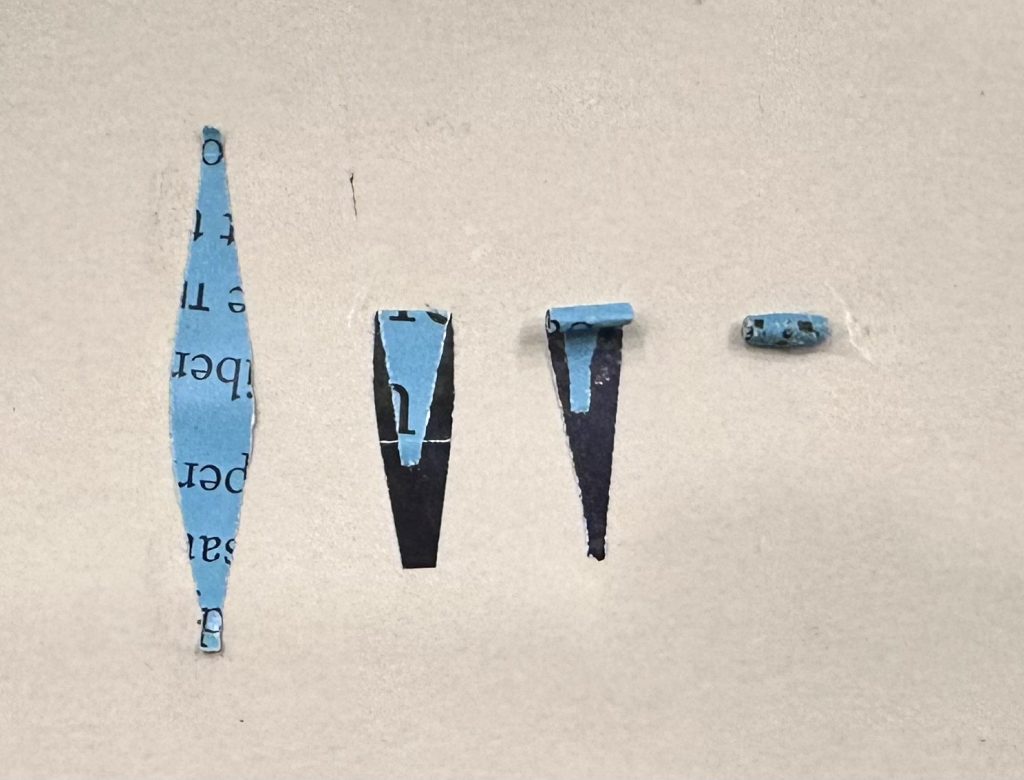

Originally, my studio did not have running water and I was using a rain barrel to wash my brushes. Seeing the pigment wash into the ground was frustrating . I was watching the pigment poison the ground. I began using fabric to absorb the pigment in my dirty paint buckets and suddenly realized I had found my next chapter in creating art. This is what i call I my “aha moment”.

I found old metal objects that had been stirred up from the earth and began using these to create rust on paper and fabric.

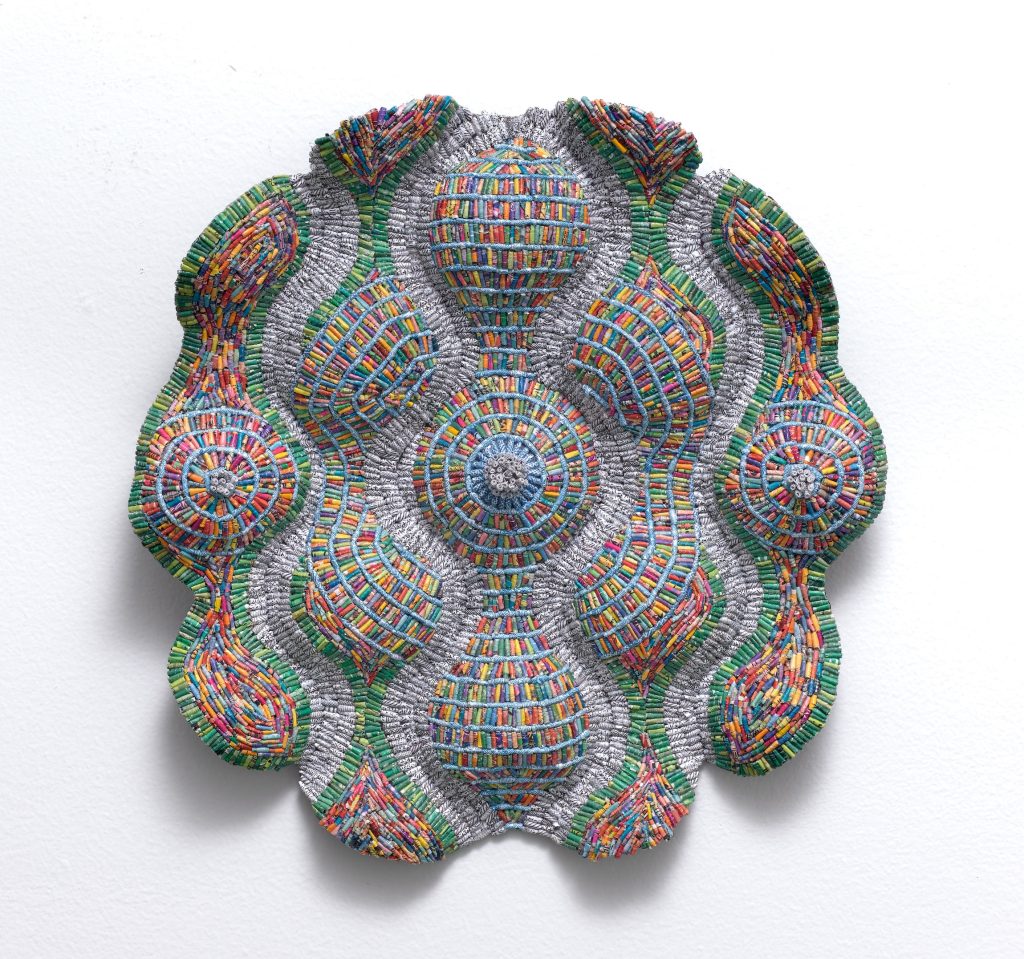

The peaceful and quiet rhythm of isolation on the farm combined with the need to be environmentally conscious and sustainable created the “Fabric of Being “ collection!

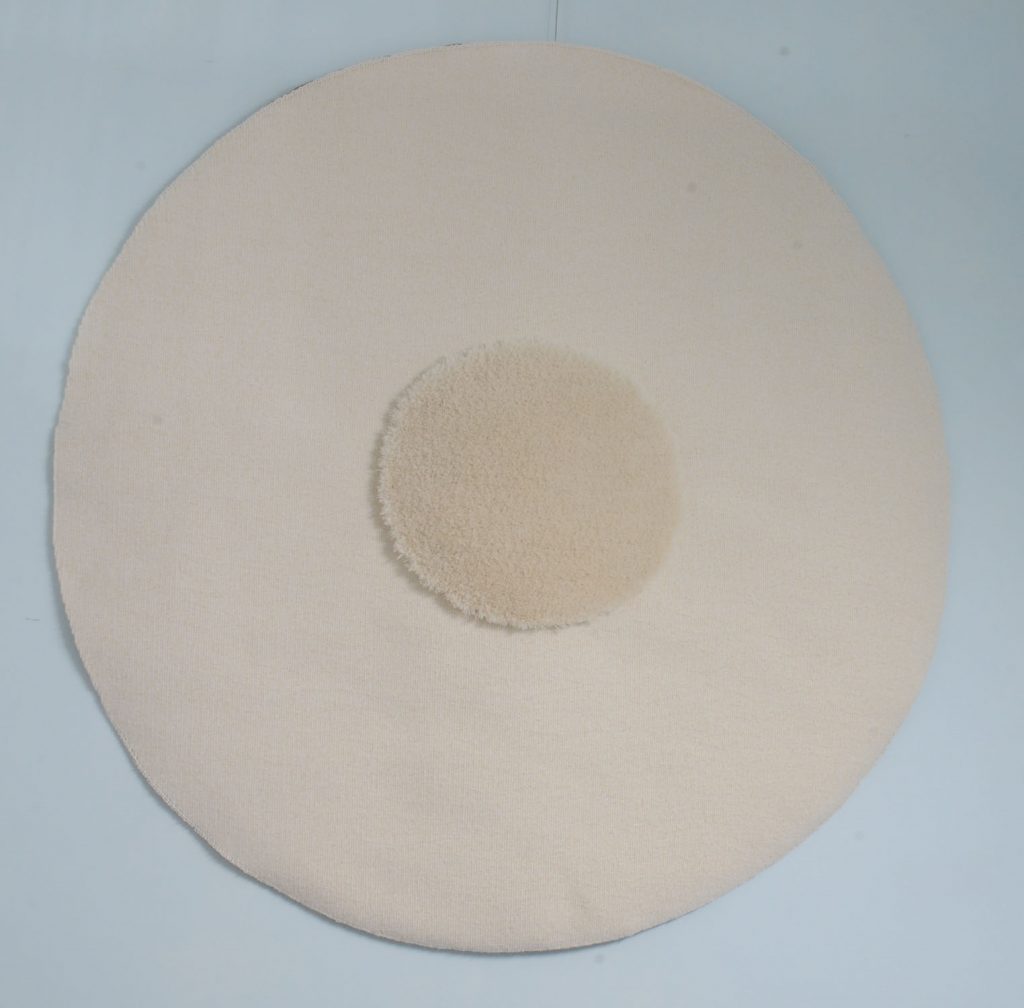

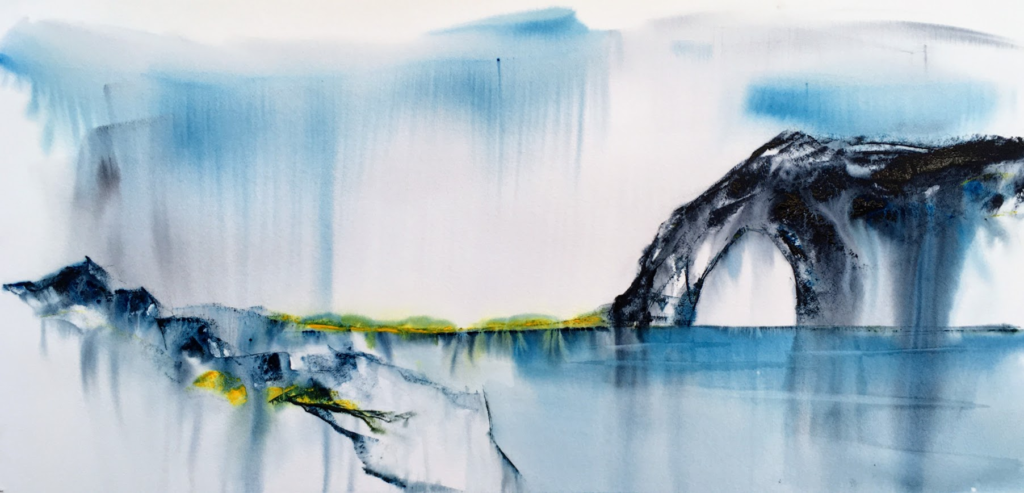

Discuss how you use college and fabric in your work.

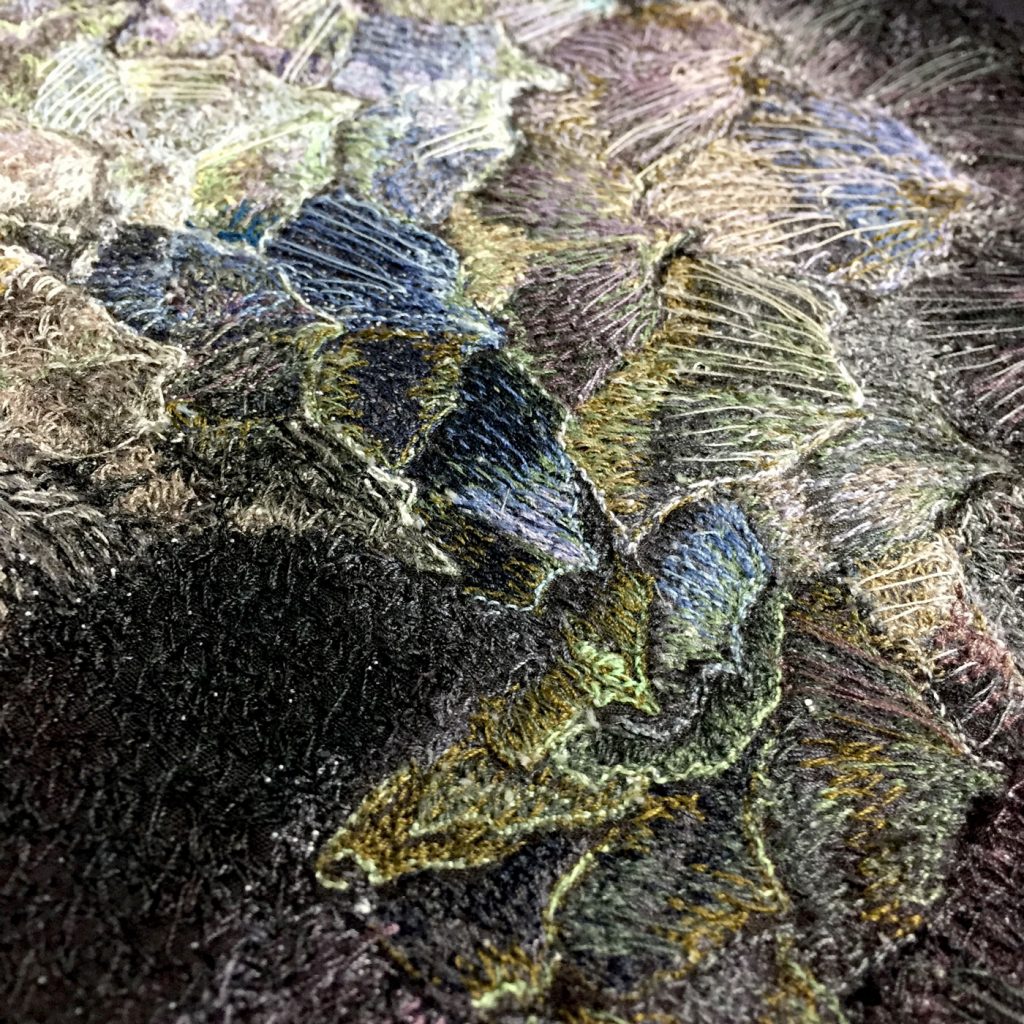

I use collage and fabric to create compositions that evoke an experience. The majority of my work is on a large scale, to have the viewer stand within the paintings. The process is my passion. I have dyed fabric hanging from clotheslines and rolls of paper strewn across the floor covered in watered down paint. Once dry, the dyed fabric and paper is torn into monochromatic compositions. My paintings are a form of propagation.

Taking a piece of a whole, planting, nurturing, and duplicating my surroundings. The weave of the fabric is represents my integration with nature and the symbolism of being interconnected with our environment.

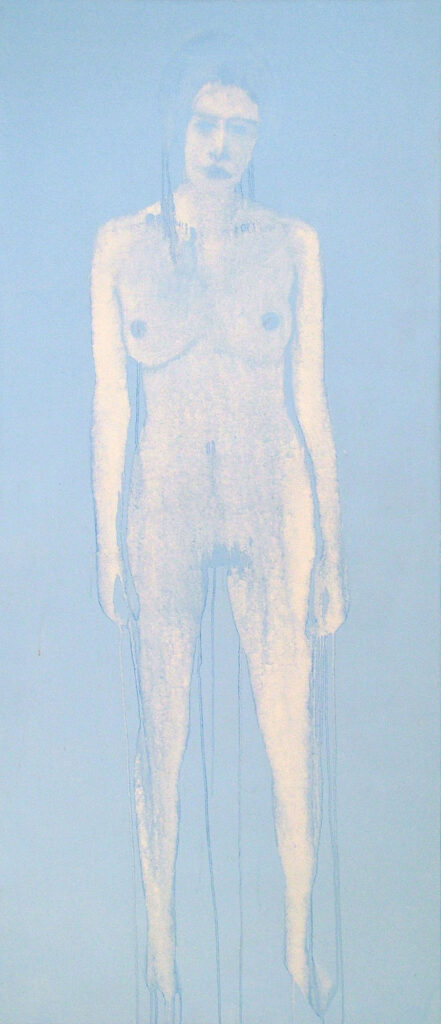

How strongly has your art been influenced, by your formal art training?

The art I create today could have been accomplished with or without formal training, but I believe that when we learn how to use multiple “tools”, it allows us to find ourselves in our art. Life drawing, realism, sculpture, basic disciplines allowed me to free up space for the creative process to flow. As a multidisciplinary artist, I am able to create with fluidity of thought without guessing the process. Knowledge is freedom to tell your own story.

What method of recording do you do when you travel?

I love to collect organic forms from the area that I’m traveling. Branches, rocks, shells, feathers, bones, sand, anything tangible as diaries of the adventure. I also have been known to send myself postcards! One of my favorites is a postcard i sent to myself from Abiquiu, New Mexico, USA with a photo of Georgia O’Keeffe riding passenger on a motorcycle in 1944. I write simple notes to myself . These tangible diaries create the shrines throughout my studio.

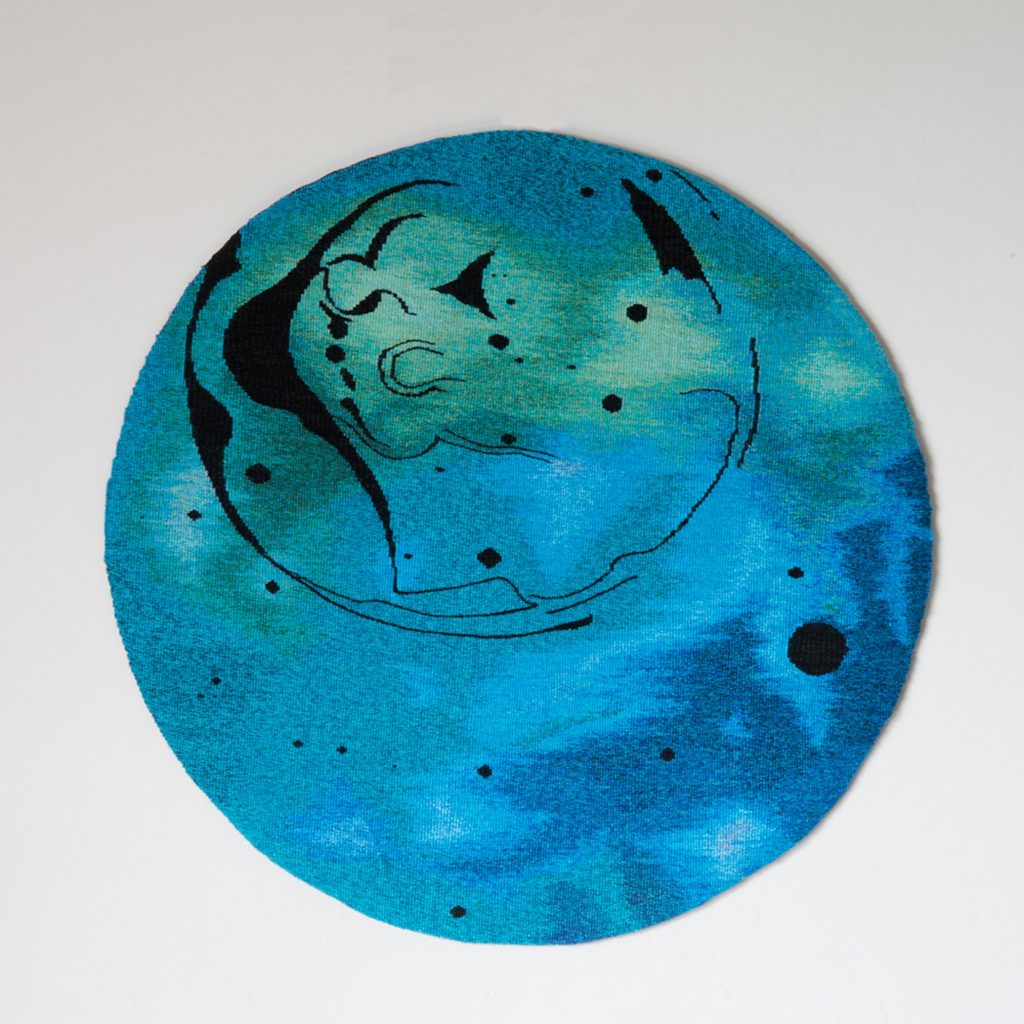

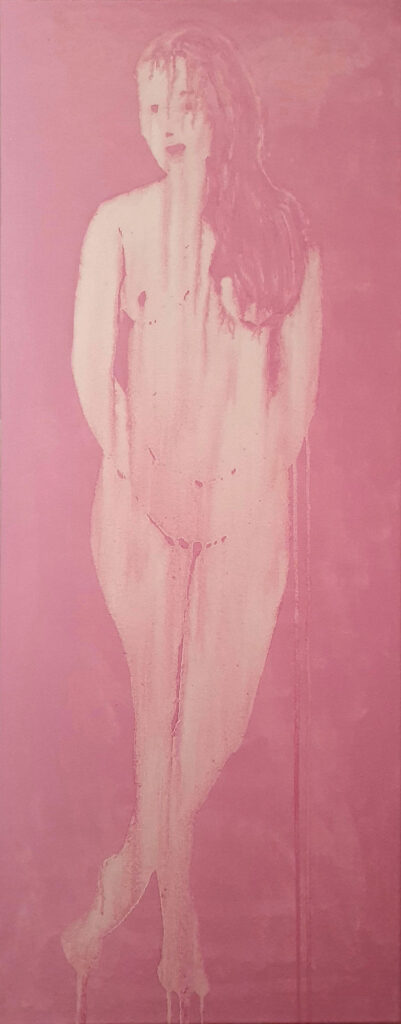

Discuss the femininity of your work?

Women and nature have an undeniable bond. My art is representational of nature. That is why my art has femininity.

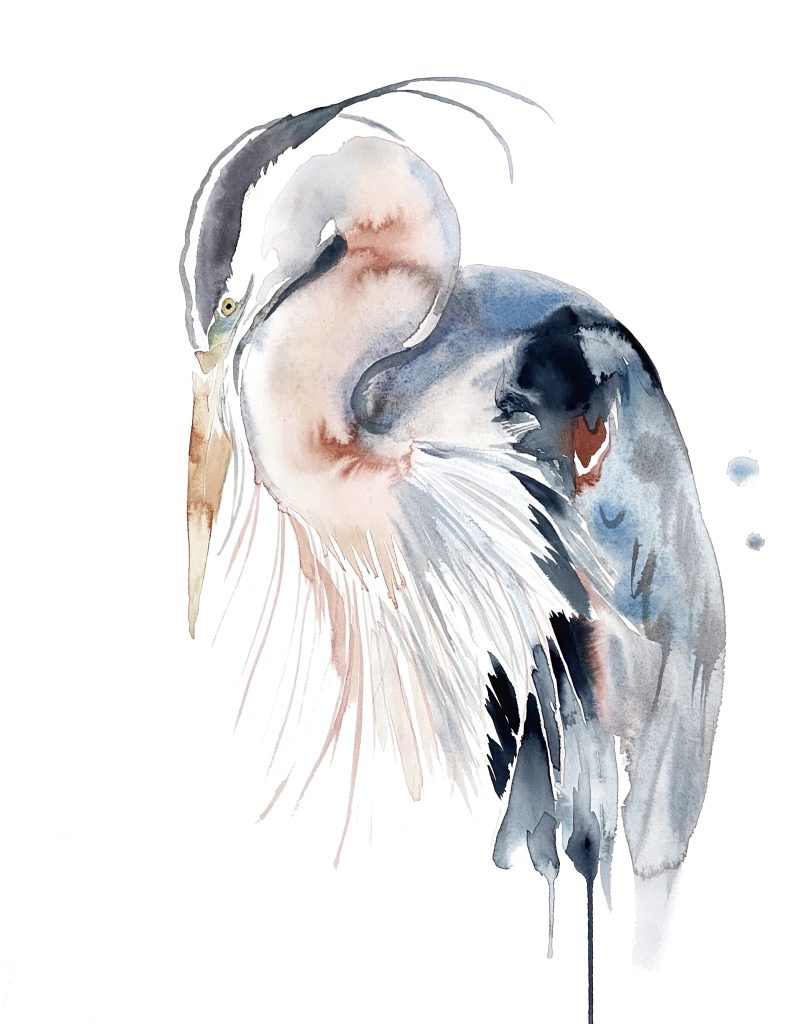

‘Of Light and Water’ I, 48"x 48" Mixed Media on Canvas

‘Of Light and Water’ I, 48"x 48" Mixed Media on Canvas

You have work in both private and public collections. Please take one that you were sorry to see go but also delighted to where it went and why?

In the beginning of my art career, I held fast to the emotions surrounding individual paintings. Now, many years have passed, and my emotional investment in the individual painting is severed when it leaves my studio, giving space for my mind to breathe into the next piece of art. My emotional connection has fallen into the love of the process. The meditative actions taken in dying of the fabric, hanging the fabric, pooling water onto paper, and composing compositions. This is what I hold dearly.

‘Of Light and Water’ II, 48"x 48" Mixed Media on Canvas

Discuss how multi layering brings out unexpected results in you art.

I believe the canvas already has a plan, and I am its tool. The delicate surprises of color change when the underlayer of paper is combined with the sheer top layer of a dyed fabric, is comparable to mixing color on layers of transparent film. Repeated to achieve deep organic hues. Combined with the different size of weave in the fabrics , the folds become deep crevasses exposing small peeks of rust. A focal point of warmth trickling through a monochromatic sequence of layered color. The multilayering is unpredictable, and the outcome is unpredictable as well. I simply allow the painting to transform and trust the process.

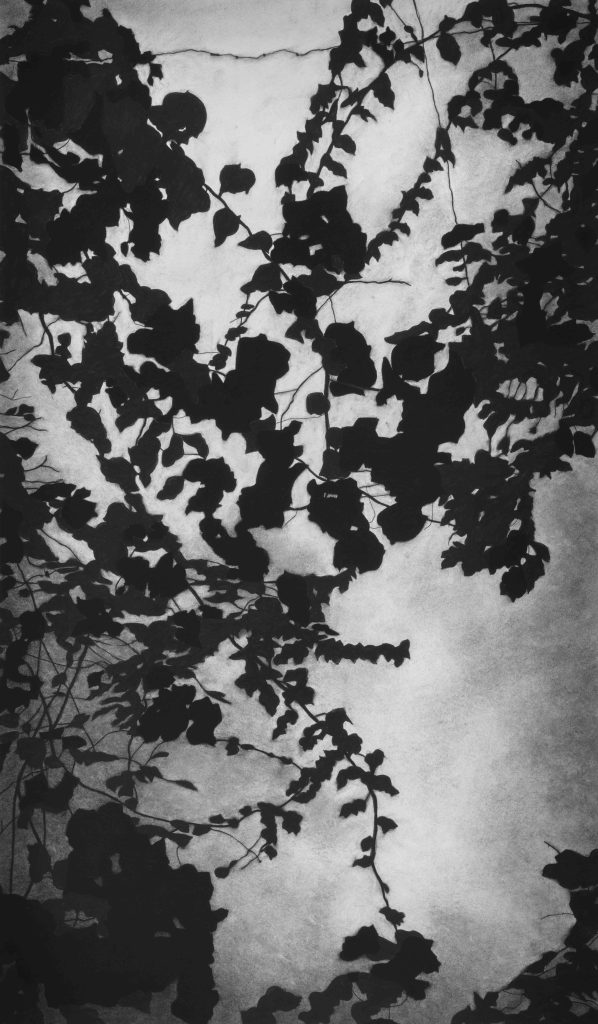

'Willow' 1 70"x 60" Mixed Media on Canvas

Comment on your current colour palette.

I lean towards a monochromatic color pallet. The color inspiration is influenced by my surroundings, also inspired by travel. I will bring the ocean or the desert home to the mountains and recreate the colors on the canvas. It’s a visual diary for me. I travelled to Joshua Tree National Park and the surrounding area of California several times this past year. In my current exhibition in North Carolina, USA , the colors depict warm tones, deep grays, and whites. I brought the high desert to North Carolina! Carolina! grays, and whites I brought the high desert to North Carolina!

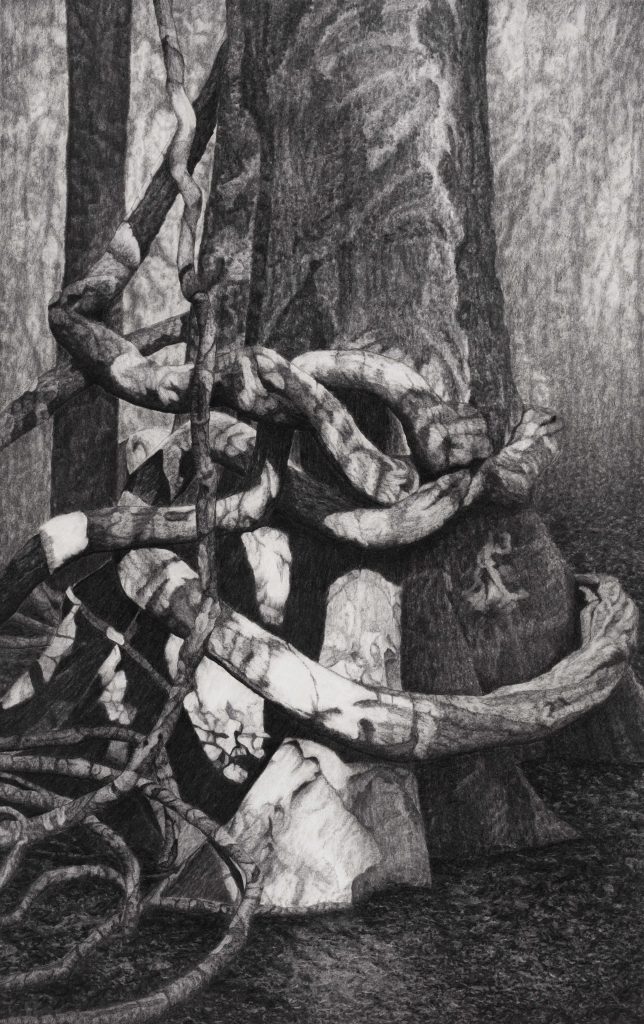

'Wind Moon Howling' I 48"x 48" Mixed Media on Canvas

How do you compose landscapes to give such a calming embodiment?

I am fortunate to have found my place of serenity in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. I watch the ever-changing landscape of the weather, mist, fog, clouds, sun, moon, and seasons from the farm. I try and capture the movement of the elements in the form of collage. By using the thin delicate weave of fabric, and haphazard placement, i attempt to mimic the serene. This ethereal display of nature is the inspiration of my landscape paintings.

'Wind Moon Howling' II, 48"x 48" Mixed Media on Canvas

Discuss your amazing studio….

The studio was the first structure able to be used when we began the work on our homestead. It was a shell of a structure, so getting it up and running was a huge undertaking and it’s still very rough around the edges. The studio sits above the barn . The sounds of the goats, chickens and ducks echo over my music, and at night the frogs sing around the pond in chorus! in chorus!

It is my sanctuary, oasis, and a space where my mind can open. I have 1200 square feet of raw work space with multiple windows and glass doors to allow for the natural light. Through the glass I can see the pastures, the pond and all the trees surrounding the studio. An extra large, table is in the centre of the space, and is used as my main flat surface for the focus painting.

There is an area that I have dedicated to a lounge/sleep space, decorated with found objects of wood, bones, feathers, rocks, and shells. These objects are my “collections” from my travels and from around the farm, and they are displayed in shrines to nature over a drawing table. It’s a very thought provoking, space and is rough enough to feel free to explore my art in all mediums!

In 2023 you had five exhibitions – how do you keep up the pace.

It all circles back to the rhythm of the farm, and the isolation that allows me to focus on my art. I’ve been an independent artist for years, and self-discipline is a necessity to achieve the goals I set for myself.

I found that integrating my life on the farm and my art, and seeing them, allows space for freedom of thought and creativity. When the opportunity presents itself to exhibit my work, I jump at the chance to have a vision come to life.

Contact:

Lauren Betty Art

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June 2024

Images on these pages are all rights reserved by Lauren Betty

Claire McCall

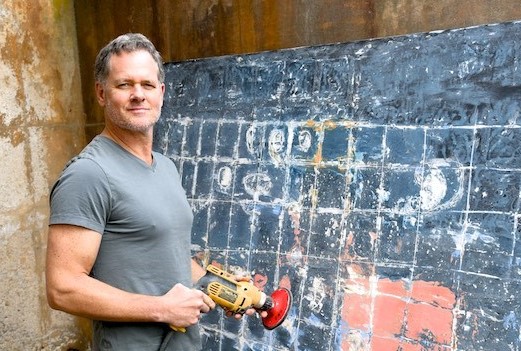

Why do you find, using palette knives so satisfying in your work? How many sizes do you use?

I love the buttery texture of oil paint and find the use of palette knives very satisfying as you can create thick impasto passages and then move the paint around as you wish to blend edges or create movement in the paint with directional strokes. I generally stick with 2 sizes unless I am working on a very large canvas. I use a medium size knife with rounded edges for background work and a small knife with a more pointed tip to work with fine detail on figures.

How did ‘place’ become such an important part of your art?

I like to think that the viewer can translate my paintings to their own place in terms of space and in terms of their own world. With figures generally turned away from the viewer, one can easily put themselves or family members in the painting.

Another Day Done

How large and small are your paintings?

My paintings vary from 30cm x 30cm to 120cm x 120cm with various dimensions in between.

Comment on your statement, …”the drama of abstraction vs realism’ in relationship to your work.

When I start painting a work, I will first complete the background. My backgrounds are quite abstract with free palette knife movement and mark-making with the tip of the knife. The figures or a focal point will then be carefully constructed with a solid foundation amongst the thick impasto abstraction.

A Picnic Lunch

This is the more detailed realism for the eye to focus on initially before being swept around the painting.

Why are there so many of your paintings done at the beach?

Sandcastles

Sandcastles

Apart from the fact that I feel at home by the ocean, and I spend my vacation time in this environment, I think the beach landscape suits my style of painting with its texture and movement. Colourful umbrellas and people in a relaxed state are also an endless source of inspiration for multiple painting compositions.

Take your painting, “Beach Cricket” and discuss.

The Beach Cricketer is a figurative work that conveys a classic pose of a child playing one of the all-time favourite activities of a beach holiday, beach cricket. It is a memory that many people can relate to and can include lots of motions that help to convey movement in my painting. The figure wears a cap hiding the details of his hair and face. This gives the viewer a chance to put themselves in the picture.

Beach Cricket

Is it your aim to record the feelings of Australia and our times at the beach?

I do love the old impressionist works of figures at the beach by artists such as Edward Henry Potthast who convey a different era of beach costume and would love my paintings to be a record of this point in Australian history.

Beach Ball

Beach Ball

Comment on your thoughts about entering art shows.

Art shows are a perfect place for an emerging artist to begin showcasing their work to a broader audience. It is not so much for the prizes as judging is a subjective process, but to regularly exhibit at art shows is to become known by regular art show enthusiasts and I have often been approached for commission work when my works have been seen by collectors at art shows on a consistent basis.

Where has this led you and your art practice?

I did enter the Camberwell Art Show with my very first painting back in 2003/4 in complete ignorance to the high standard of work that would be on display. Of course, it did not get hung, however I did use this show to measure my progress. In the next year, I did get hung, and sold a couple of pieces the year after. Three years after my first attempt at this show, I won ‘Best Representational Work In Show’.

Ice-Cream

My art practice has been driven by my unwillingness to give up even in the face of rejection.

“Painting is easy when you don’t know how, but very difficult when you do” Discuss this quote in relationship to your own art.

The more you learn of course in art, the more you find out how much there is to learn. When you don’t know how, I guess it’s easier to simplify the process. I have developed my method over a number of years and all of the elements that go towards composing and completing my paintings become second nature, but it is a complex process which can only come together with many failures and successes behind you as experience to draw on.

Beach Umbrellas

Are the children in your art your own?

My earlier works featured my own children and often a friend’s children.

Age of Innocence

Take, “The Lifeguard” and add the other elements of beach life you paint and why?

The Lifeguard features a lone figure however adding a seagull flying past or the lifesaving flag in the distance can add context for the viewer and provide more atmosphere and elements for the eye to focus on.

Lifeguard

What or who inspired your art and what and who encourages you now?

I have been inspired by many local artists in Melbourne. I am a big fan of the Melbourne Twenty Painters Society. Many members are impressionist painters and I enjoy their annual exhibitions. I am inspired however by many genres of art and I look forward to studying the works of the masters in galleries around the world as I find myself with more time on my hands now that my children are older.

Discuss painting light and particularly, bright light.

Light very much dictates my attraction to a scene that I might paint. I particularly like late afternoon light as it turns golden. I pay close attention to the direction of light and the colour of the shadows to give the painting an overall warmth. Bright lights can be added at the very end to really turn up the highlights.

At the Beach

When the weather turns, what do you paint?

I would normally gravitate towards sunny days to paint outdoors otherwise I can work from source photos.

Discuss your studio and one or two objects that your love having in it?

I love the very tall windows of my studio that give beautiful light to work in.

How do you capture the magic moments, in a sketch book or photos?

I very much prefer photos over sketches as I am concerned with light and colour in my compositions.

Contact:

Claire McCall

clairemccallart@gmail.com

Victoria, Australia

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May 2024

Images on this page are all rights reserved by Claire McCall

Linda Coomber

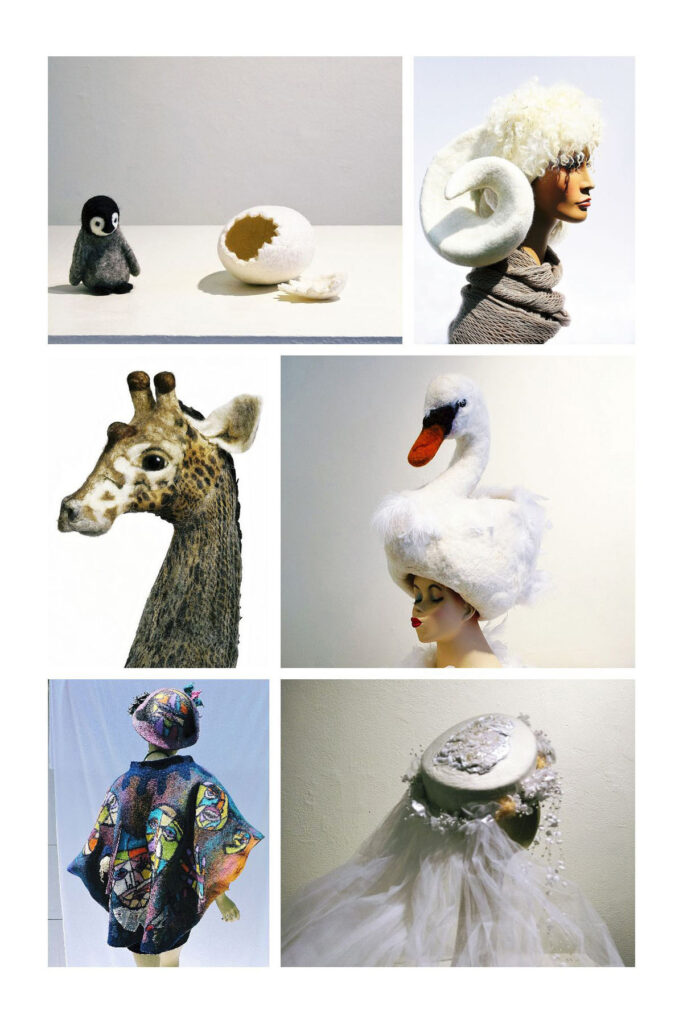

Explain what led you to basket weaving?

My interest in basketry and fibre art is a mid-life phenomenon that grew out of a need and into a passion. Having recently moved to the Mid North Coast of NSW, Australia, I acquired some beautiful old wooden chairs with caned seats. The caning was damaged and broken. I searched around for someone to fix them, and a friend introduced me to Helen Beale, one of Australia’s most talented caners and weavers.

Helen declined to fix my chairs but offered to teach me how to do it myself. Out of those caning lessons came basketry, weaving and fibre art.

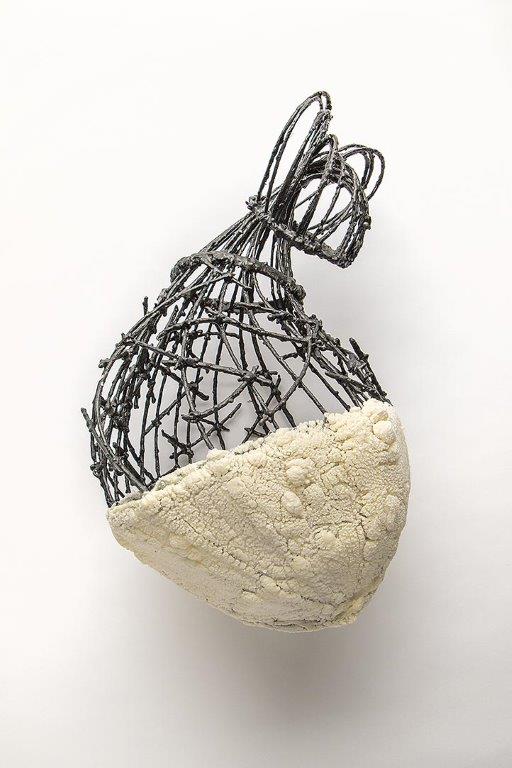

Black

Why do you source your materials locally rather than using traditional flax?

Every area, indeed, every country, has its traditional weaving materials. In the UK and Europe, it is mostly willow. In native American weaving, sweet grass, pine needles, wicker, spruce root and cedar bark are all used. Anything pliable can be used in basket weaving as long as it is bendable and can form a shape.

I’m still learning and experimenting, and try many different leaves, vines and grasses that grow in my local area, as well as more traditional materials from my area, like Pandanus and Lomandra.

Dracena

Describe the landscape around your studio?

I live on Gumbaynggirr Country on the Coffs Coast of NSW. My area is made up of beaches, headlands, rivers, estuaries, creeks, mountains, and flood plains. It is a diverse and beautiful landscape. Both native and introduced plants grow vigorously in our temperate, humid climate – rich pickings for a scavenger like me!

Collecting seed pods and similar materials is the make of your work. Discuss how they are added to your work.

Clay Base

My weaving is a mix of traditional basket weaving techniques like twining and plaiting, but I also use coiling, where I sew together coils of natural materials using a strong waxed thread. This allows me to add embellishments like stones, shells, and seed pods, which are sewn directly into the work.

Being a scavenger is fine, but where do you store it all?

Yes, storage is a problem. Luckily, I have an airy, dry area under my house, and a very understanding husband!

Mould is my enemy, so once my materials have dried out, I hang them from racks suspended from the ceiling in our garage. That way they stay clean and dry until I need them. Larger pieces are stored in cardboard boxes and paper bags. Air flow is important, so no bags or boxes are ever sealed.

Is this a seasonal activity?

Certainly, in many parts of the world, collecting weaving materials would depend on the season, but in my area, where temperatures are mild all year, I am able to collect all year round.

Driftwood Rush

Expand on the process you take in using local plants to produce a suitable material to weave with.

I’ll use two examples. Lomandra, also known as mat rush, is a perennial clumping plant with long, strappy leaves. They are native to Australia and grow abundantly in my area. I cut handfuls of the leaves close to the base of the plant. Once I’ve harvested the leaves, I think I’ll need, I’ll take them home and spread them out in the direct sun. Within three days, the leaves will curl and dry to around one third of their original width, but they will still retain their green colour. At this stage, I use a sharp needle to split each leaf into thin strips. These strips are quite pliable, and ready for weaving.

The Radiata Pine tree is also very common in my area. It has long needles that when dry, are a lovely red brown colour. The tree sheds its old needles all year round, so you can collect them straight from the ground. After I’ve rinsed and dried them in the sun, I store these in a cardboard box, ready for use.

Serenity Stones

What is the drying time needed?

This varies greatly. Some, like the pine needles, are already dry when I collect them, but most strappy leaves will take a few weeks to dry out completely.

Do you add colour, either natural or manufactured dyes?

I don’t use dyes. I prefer the lovely, earthy colours that that are inherent to each variety of leaf or plant that I use. If I feel the need to add colour, I’ll do it by using coloured waxed thread, particularly in my coiled pieces.

Palm Sheath

A special twist in your work is the use of introduced deer antlers, discuss.

Antler 1

Antler 1

Deer were introduced into Australia from Europe in the 19th century as game animals. Today, they are feral animals in many areas throughout Australia and cause a variety of environmental problems, unfortunately. Fallow deer are particularly abundant in some areas of NSW. Many people don’t know that deer shed their antlers naturally every year, and then grow a new set. They will often rub up against a tree until the old antlers fall off, so it’s not uncommon to find a set together beside a tree where deer are common.

Antler 2

These naturally shed antlers are beautiful, tactile things. Anywhere in length from 40cm to close to a metre, I have found they make wonderful, dramatic handles to my woven baskets. Their colours are beautiful too. They can range from dark brown to almost white.

Are there any local restrictions on the collecting of plant material?

Aside from it being terribly rude to raid a neighbour’s garden without permission, no, there are no restrictions in my area! I make sure I selectively harvest – I never take a whole plant, just a handful of leaves; after all, I’ll probably want more sometime in the future.

How do you define your work, artwork, or useful artistic objects.

I consider myself a weaver. Weaving is almost as old as human history. Traces of baskets have been found in the Egyptian pyramids, and woven basket liners have left their impressions inside the fragments of ancient pottery.

Baskets and woven materials were needed as containers, clothing, floor coverings, storage and for transport. Almost all cultures used and experimented with the natural materials around them to create woven objects.

In our modern lives, we no longer need to weave our own clothing and floor coverings, but I like the notion of bringing the natural world into our interiors. By beautifying and texturizing our living and working spaces, a statement can be made about valuing artisanal objects, whether considering them as artworks worthy of putting on our walls or as useful objects to be used daily.

Your background in psychology, has it helped with your artistic practice?

If it has, I’m not aware of it!

Take ‘Jacaranda Vase’ and discuss.

Jacaranda trees are very common in my area. Most people will know them for their gorgeous violet coloured flowers, but they also have the most beautiful woody seed pods. I use these seed pods to decorate some of my vessels, and they are particularly lovely around the top of vases. To make the vases suitable to hold fresh flowers, I’ll often build the vessel around a glass insert. That way the vase is a usable and useful piece of art.

The sizes of the vases can vary from 20cm or so to very large pieces that are half a metre in height.

Using locally foraged plants means that I never run out of materials for my pieces.

Comment on the importance of the local artistic community in giving you the opportunity to define your own art.

For the last five years, I have been the gallery manager of our local community art gallery. The Art Space Urunga is entirely staffed and managed by volunteers and supports local established and emerging artists in all mediums. One of the benefits for me has been that through meeting many other artists, I have been able to collaborate with several to combine their skills with mine. For example, I have worked with several potters to design bases for my weaving. A glass artist has made gorgeous luminous glass bowls for me to weave around. Currently, I am working with a local woodworker who is making handles for my pieces from beautiful local timbers. These creative collaborations have brought complementary skillsets that have enhanced my projects.

Vase

You take local workshops, how does your teaching qualifications assist you within the classes?

I have learned through classroom teaching that, no matter what the subject is, it is important to try many different approaches when teaching a skill. Some people respond to what you say, whereas others may learn best by watching and doing. Teaching has also taught me that follow up is vital. Whether I’m teaching someone how to make their own twine or how to make a ribbed basket, I always have notes with detailed instructions and photos for people to take home. You can’t remember everything you’ve learned in a workshop, so handouts can remind you of processes and techniques you may have forgotten.

Palm Platter

How do you extend your students to go beyond the expectations of a basket?

I am constantly surprised by people’s innate creativity. Once the basic methods have been mastered, the resulting baskets from workshop participants are rarely the same. Each individual’s choices of specific materials and how to put them together leads to very different results.

Do you take commissions?

Yes, gladly.

Contact:

Linda Coomber

Details

Linda Coomber

New South Wales, Australia

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, May 2024

Images on this page are all rights reserved by Linda Coomber

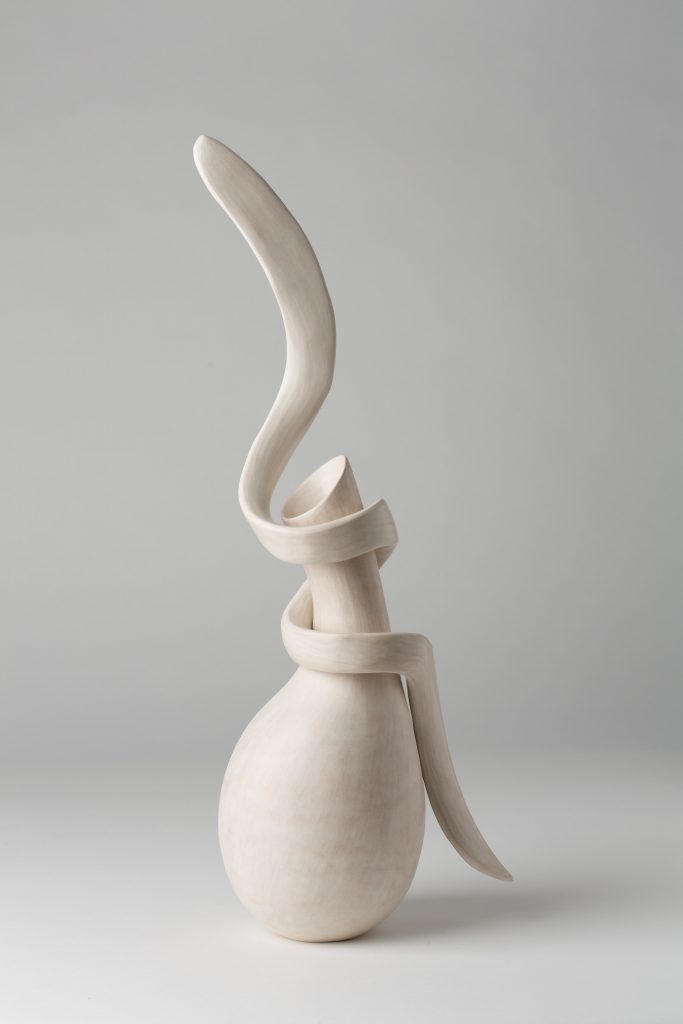

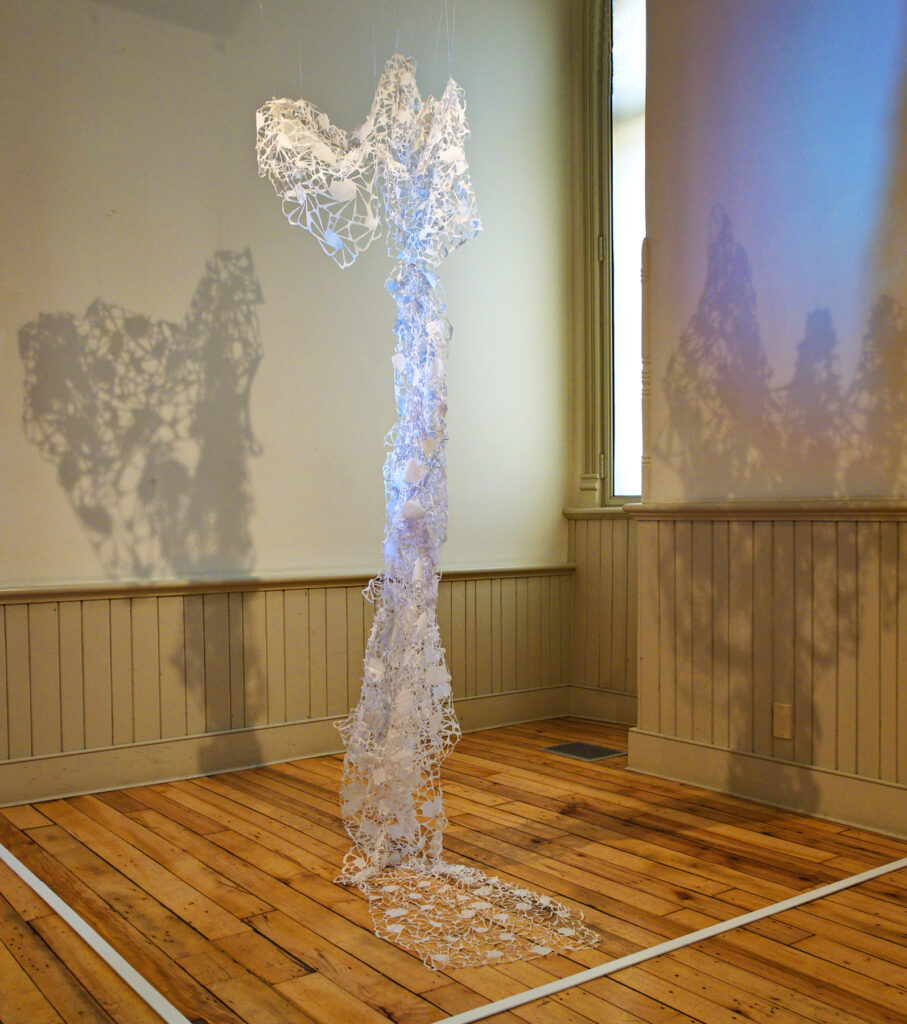

Loren Eiferman

How overwhelmed do you feel about the environment we are passing onto the next generation?

As with most of my circle, I feel very stressed about climate change. It is here and happening before our eyes. Lilacs now blooming twice a year: once in spring, and again strangely in the fall. Insects and diseases that were often relegated to the Southern Hemisphere are now prevalent where I live -- in the northern hemisphere. Spring peepers (frogs) are chirping away the first week in March instead of in April, and of course much worse outcomes including bleaching of coral reefs and many species are on the brink of extinction. This is not normal. These are indeed strange and changing times that we are all living in. But I remain hopeful that human ingenuity and knowledge will get the upper hand and be able to reign in and realign this runaway train. Both of my daughters are working on addressing climate change and are seeking fundamental new pathways to alleviate this global problem. I am proud that they and many in their generation have chosen this path, and for this reason, I remain hopeful.

Prunella Gradiflora Self Heal, 2022, 150 pieces of wood, pastel, linseed oil, 62 x 31 x 5

Do you work one series at a time, exclusively?

I used to work exclusively on one series at a time. Often working within a certain framework of what captivated my imagination for several months to years at a time. Now, it seems that I frequently hopscotch between series, and I am not rigorous about sticking within the confines and parameters of a particular series anymore. I find myself experimenting and playing more these days in my studio.

Where does your current inspiration come from?

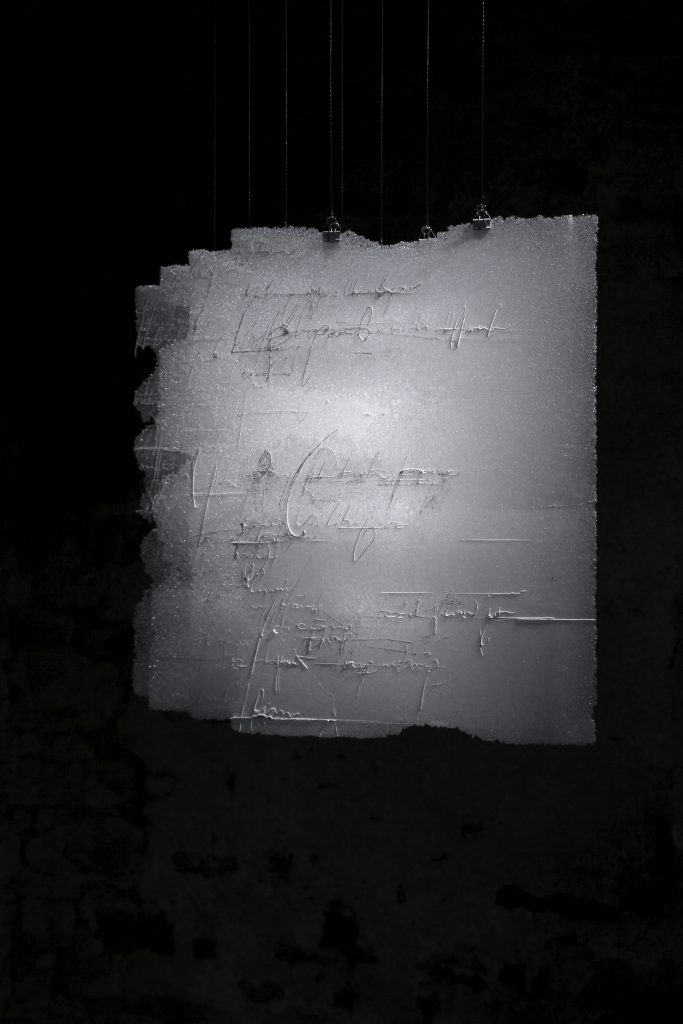

My current body of work is inspired from different sources. One source is the mysterious illustrations found in the late 15th century Voynich Manuscript. This manuscript was written in an unknown language, by an unknown author and filled with botanical illustrations of plants that don’t exist in nature, past or present. For the past eight years I have been translating the botanical section of the manuscript into three-dimensional wood sculptures.

Another source of inspiration is the black and white photographs from the early 20th century German photographer, Karl Blossfeldt. He photographed nature in extreme close-up and the photographs from his seminal book, “Urformen der Kunst” (“Original Forms of Art”) are extraordinary. The way a plant curls or the shape and color of a tight bud always inspires me. It is ultimately the nature that surrounds me, in all her myriad forms and wisdom that I draw daily inspiration from.

You collect most of your material locally. What is the process from then?

I start out every day with a walk and collect tree limbs and branches that have fallen to the ground. I never chop down a living tree. I carry those sticks back up into my studio. I then let the wood sit for many months in what I call my “sea of sticks” to make sure the wood is dry and won’t check or crack. I usually do a drawing first and that drawing acts as a road map of where I want the sculpture to go. From there, I start looking for shapes found within each stick to correspond to the lines found in my drawing. I then cut small naturally formed shapes, joining these small pieces of wood together using dowels and wood glue. Next, I make a putty to fill in all the open joints. I then wait for the putty to dry and sand the putty until it’s smooth. The goal is to make the line of the wood seem continuous and all the joints appear seamless. I usually reapply the putty, wait for it to dry, and sand it at least three times. I want the work to look as if it grew in nature, when in reality, each sculpture is built from hundreds of small pieces of wood that have been meticulously crafted together.

I think of my sculpture as drawing, but in wood. This is a very time-consuming process, and each sculpture takes me a minimum of a month to construct. I frequently work on two sculptures at a time since there is so much down time waiting for the putty to dry.

When and why did you decide to work with wood?

It’s been a long circuitous route to get to where I am now. I used to be a painter. I was working in my tiny apartment in Manhattan’s Little Italy, making large oil paintings on paper. I had three studio walls that were filled with nearly completed paintings. On one particularly hot and humid August day, the paint wouldn’t dry, and I had no more wall space. I was stuck with three very wet paintings that couldn’t be moved. I am wired to always be making and creating art. Since I couldn’t paint, I instinctively picked up a piece of balsa wood that I had been using for a framing material and a straight edged razor blade and inexplicably proceeded to whittle away. Literally time stopped. After eight hours of being in an almost trance like state of crafting this piece of balsa wood, I realized that I derived more creative fulfillment as a sculptor than as a painter! From that point, I evolved from whittling balsa wood with a razor blade to getting a proper whittling set.

New Growth, 2021, 142 pieces of wood paper clay, linseed oil, pastel, copper metal coating with green patina, 38 x 16 x 8

Eventually, I realized that balsa wood is a terrible sculpting material and I started gathering sticks in Central Park and hauling them via the subway back to my studio.

I also started using better tools, including a small electric Dremel and now a Foredom flexible shaft tool.

I’ve been working with sticks now as my main material for decades. While my work has evolved from totemic style carvings of my earlier period into a more nature-inspired and botanical direction, my material, and my decades-long love of working with wood has remained.

Lunaria 2024 78 pieces of wood, pantyhose, 50 x 157

Tell us about your commission with the MTA Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

How did the commission come about?

I received a call from the director of the MTA/ Arts and Design saying I was one of five artists chosen for a commission at the Metro North Station in Pelham, NY. I didn’t know how that happened since I never even applied to the open call. I later found out that one of the curator judges on the panel put my name forward. So, I went about visiting the train station, learning about the history of Pelham and synthesizing many ideas to come up with a way of working in metal. I created a vision board with my proposed ideas for the project and happily I received the commission.

What were the perimeters?

The project was open, to all ideas, and we could design anything we wanted. We were given a budget, and I originally had another whole design that was to run the length of the station’s platform that would’ve been attached to the overhang--but that ended up becoming too costly. So, I scaled it back to have the eight black steel panels built into the stations existing railings, which is the project that was ultimately commissioned.

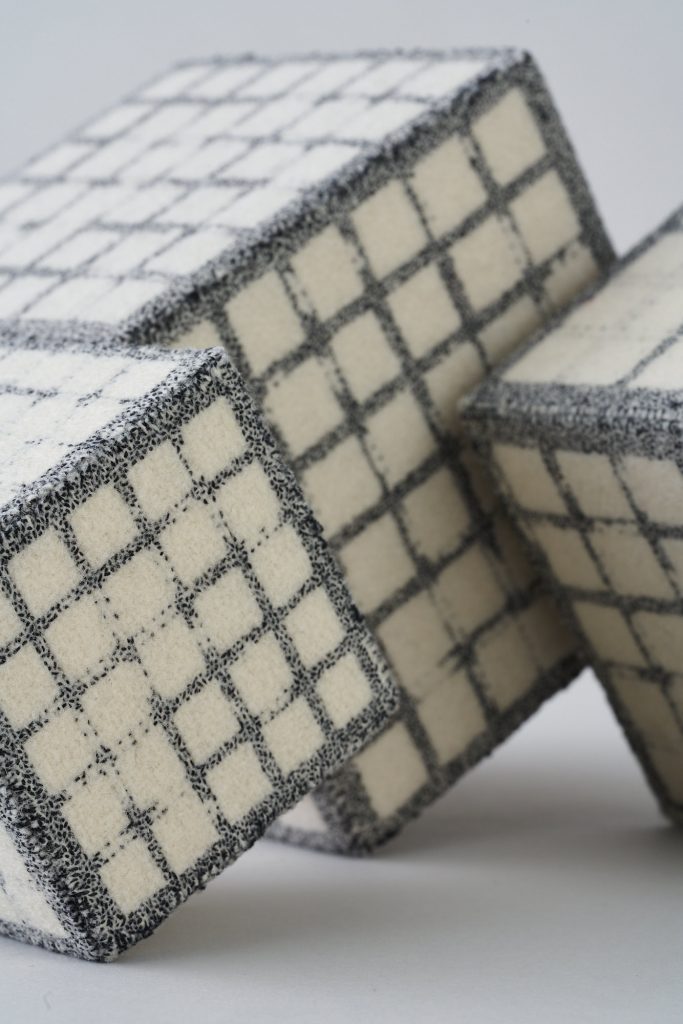

What was the inspiration?

I researched the origins of the Town of Pelham. I discovered that the Town of Pelham was incorporated in the late 1880’s. During that time, William Morris, the Roycrofters and other popular designers from the Arts and Crafts movement were active. I wanted to emulate the carpets and wallpaper designs that were commonly found inside the homes in Pelham Heights at the time of its founding. So, I came up with the concept for “Home: Inside/Outside” where I designed eight tri-layered panels made from textured black painted steel that emulated the patterns of these carpet and wallpaper designs. There were three separate iterations that were installed throughout the station’s hand-railings. The shadows created by these panels were integral to the design, such that standard MTA railings now can be read as vertical planks of wood flooring across the platform and the panels that were built read as interspersed carpets within that flooring. I wanted these carpets to be visually contemplative, indicative of a modern-day mandala but in metal. These carpet-like screens hopefully engage the viewer into seeing new forms in the negative and positive spaces and in that moment of engagement the viewer goes back “home”, is connected to the outside from the inside, is entertained, is engaged in a new way, allowing them to meditate on the value of “home”. I wanted to convey the idea that “home” can be anywhere and everywhere one might travel, even if it’s just a week-day commute into Grand Central Station.

Butterfly cropped

Discuss the material you used and why?

I decided that my wood work would be best translated using black metal textured rods. Metal rods and wooden sticks have a similar cylindrical form, and I could texture the metal to resemble wood. The material needed to be totally weatherproof and stand up to the strict standards and guidelines of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority. I wanted the metal to appear like my wood sticks. Together with the fabricators help, we came up with a unique way of working with the metal. Like my singular process of working with wood, the metal needed to be cut into small pieces and then welded and formed into the shapes and forms I had designed. This way of working was new to both of us, and it was a very exciting process to be part of.

Lollipop cropped

Take one or two pieces of that have needed much taming.

Before I start a new sculpture, I usually do a pencil drawing first in my sketchbook. This drawing frequently is about the final form and what I want the shape of the completed work to look like. I don’t always take into consideration how I’m going to get from Point A (the drawing) to Point B (the finished work). That’s where the difficult part comes in. I am giving myself a challenging task and it’s almost like, why did I just give myself this impossibility?!! So, for instance, when I went about building “Albutilon”, I knew that I wanted all the petal like forms to touch, but I had no idea how to make that happen spatially.

Albutilon, 2022, 118 pieces of wood, pastel, linseed oil, silver metal coating, 33 x 32 x 17

So, for this work, I drew a preliminary drawing in my sketchbook, and then had to draw a larger full-scale drawing. That larger drawing became almost a dress-makers pattern that I could follow to help guide me.

Albutilon (center side super close up), 2022, 188 pieces of wood, with pastel, linseed oil and silver metal coating, 33 x 32 x 7

I laid the small pieces of wood right on top of this full-scale drawing. I had never done that before with a sculpture, but this work demanded a new way of working. This work was very complicated to build, and it took 118 small pieces of wood that were seamlessly jointed together to make it come to life.

Specimens (full view), 2018,287 pieces of wood with graphite, 46x56x5

Another work, “Specimens” had so many twists, turns and angles in it that it took me months to build. This six-part wall work was made from 287 small sometimes tiny, sometime carved, pieces of wood that were jointed together and then covered with powdered graphite.

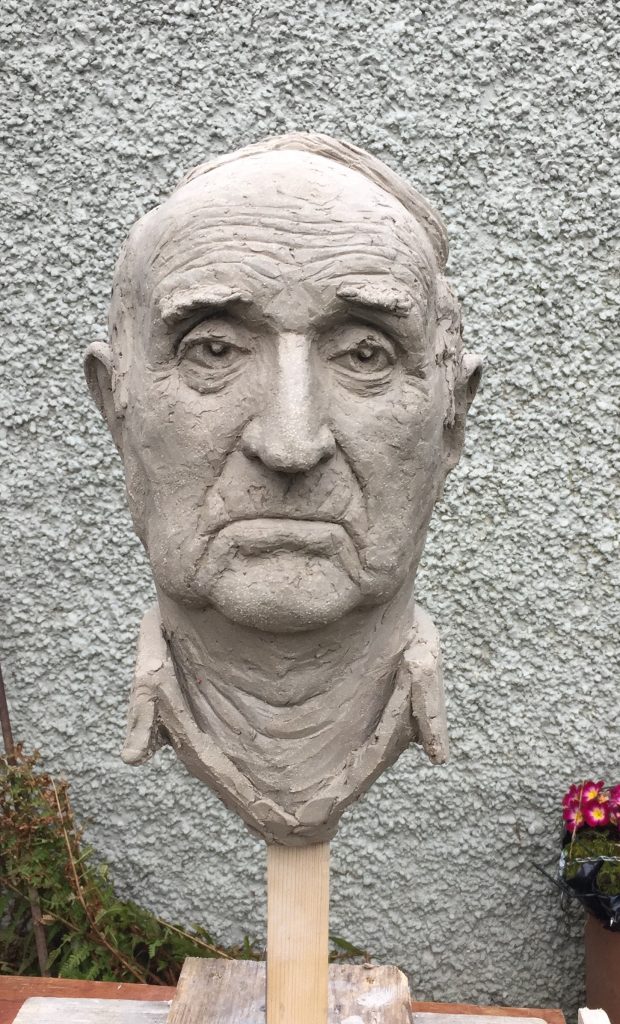

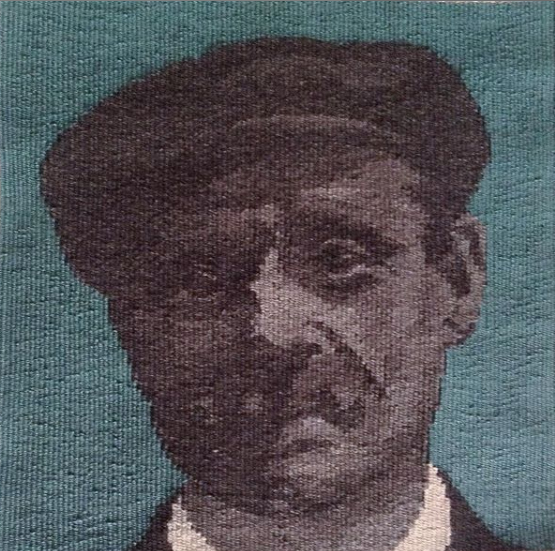

Comment on your older work in clay.

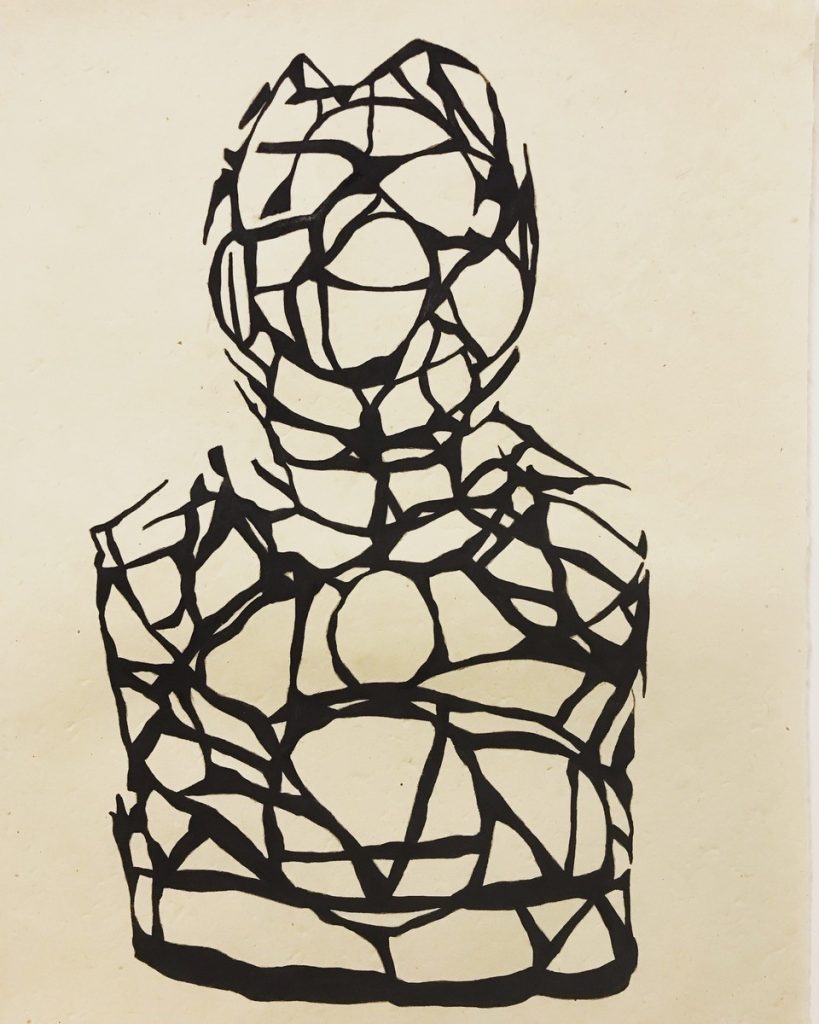

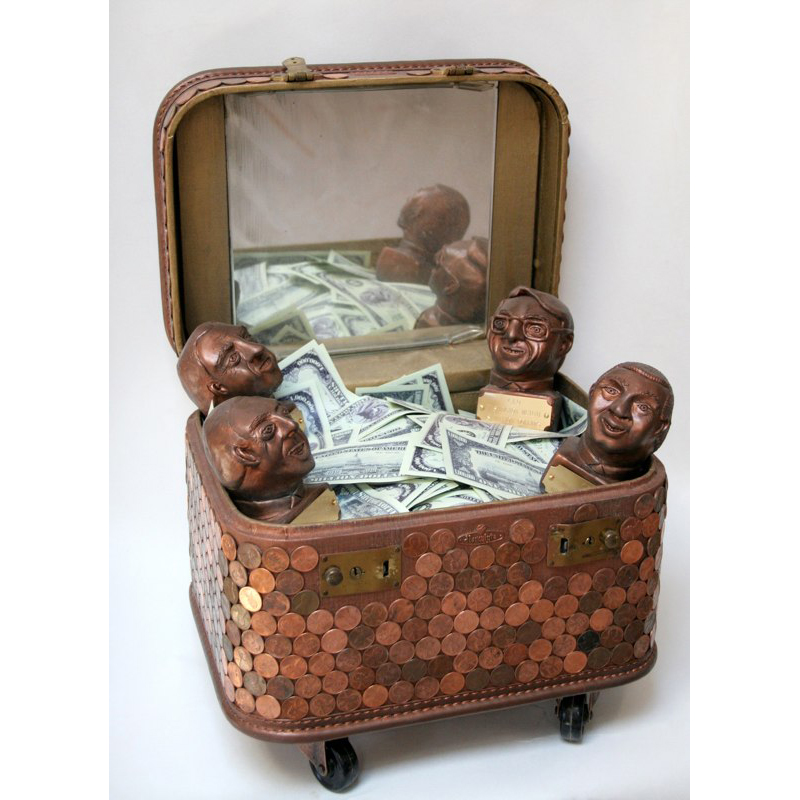

‘Take the Money and Run’.

Take the Money and Run

My clay work came about during a very difficult period for me. I didn’t have the energy or time to focus on creating my wood sculpture. Each wood sculpture needs hundreds of hours to create and build. For a year I didn’t have that calm focused energy or strength for this type of creative outlet. I needed to work with something that gave me more immediate results. I started making clay portraits that could be finished in a couple of days to a week instead of taking months to build. I started working with self-hardening clay and sculpted portraits of people that were profiled in the pages of the New York Times. This was 2010-2011, the time of the financial crash and the subsequent bank bailout, the Arab Spring, and the Fukushima disaster. These were the stories at that time that were captivating me both emotionally and politically.

The political background?

“Take the Money and Run” shows four CEOs from four separate financial institutions and how much money each made because of their golden parachute. These CEOs became extraordinarily wealthy while the Main Street investors were completely wiped out. These clay portraits were the CEOs from four financial institutions: Merrill Lynch and his $161 million dollar payday, Countrywide Financial and his $121 million dollar bonus, the CEO from Washington Mutual who made off with $18 million dollars and the head CEO from Lehman Brothers that made $22 million dollars. These four CEOs are nestled in a suitcase filled with hundred thousand dollar bills and the exterior of the case is covered in pennies. The vintage travel suitcase has an interior mirror so that the heads with an engraved brass plaques that states their financial payday are now reflected in the mirror and I put heavy duty casters on the bottom. So, “Take the Money and Run” seemed like a perfect title. This work now lives on my studio floor.

Take one clay work and discuss it in detail. Also, why you have chosen this one?

The final work from this period was a work called “Dreams of Our Ancestors”.

Dreams of our Ancestors

This work portrays seven extraordinary women, each of whom had a profound impact on a world religion. Women such as Sun Bu’er, the first Taoist; St. Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Native American ever canonized by the Catholic Church; Margaret Fell Fox, who was known as the mother of the Quakers and the founder of the Religious Society of Friends, Mirabai, a 16th century poet, mystic and Hindu saint who was devoted to Krishna and Hildegard de Bingnen who was a saint, visionary theologian, musician, polymath, artist, scientist and Benedictine abbess from the Middle Ages. These seven women are all together, resting and dreaming together on a pillow. As strange as it sounds, it was the strength and energy from these dynamic women that helped to heal my distress.

Dreams of our Ancestors detail

I realized that my source in creating art does not come from a place of anger or politics but rather from a more connected interior space. Completing this clay series allowed me to finally return to my wood work with renewed vitality and inspiration.

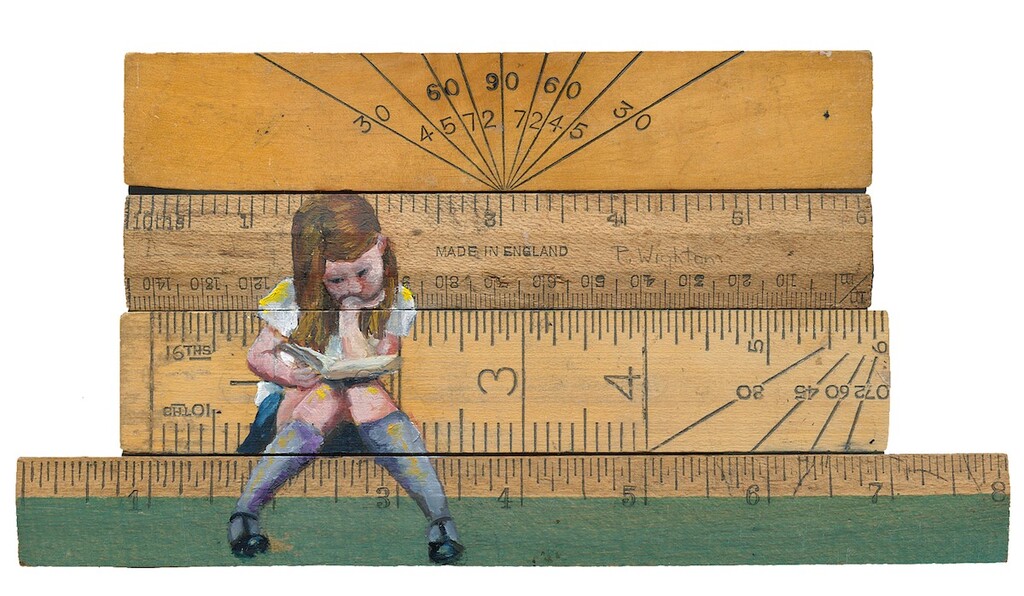

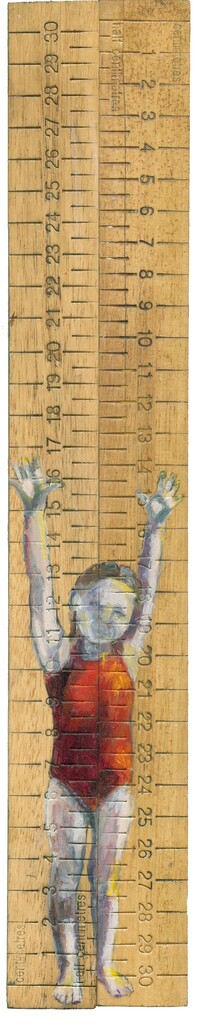

You are very diligent and do a drawing every morning, discuss.

Each sculpture that I build takes me a minimum of a month to construct. As previously mentioned, I used to be a painter, and I was really missing working with colour. I also missed the immediacy of creating work and seeing results quicker. I needed those “art” endorphins coursing through my mind and body. I also needed to be making work that takes up less physical space, something that is always a sculptor’s dilemma. I came up with what I call my “morning drawings”.

Parallel Lives

I usually read The New York Times daily and tear out images that strike me. From there I go about working on my drawing in an 11 x 14” sketchbook. Each drawing is usually based on an image found in the paper. I frequently work on the drawing when I first get into my studio in the morning, and I might continue to work on it for several mornings till it’s completed. It’s a way that I trained myself to focus and not get so distracted and be productive at the same time. I use many different materials in working on these drawings such as: crayons, chalk, powdered graphite, earth, matte medium, pen, watercolours. I had a college art professor from when I spent a year in France who taught us that if you put your body in the position of work, then the work will flow from there. This was one of the most useful words of wisdom that I learned throughout all my art classes. I repeat it frequently and it has become my daily mantra. I find beginning-starting a workday is frequently the most challenging for me. My morning drawings are a simple way to sit at my drafting table and begin to focus and start my workday.

Contact:

Contact:

Loren Eiferman

Loren Eiferman@gmail.com

Instagram: @loreneiferman

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April 2024

Images on this page are all rights reserved by Loren Eiferman

Julie Payne

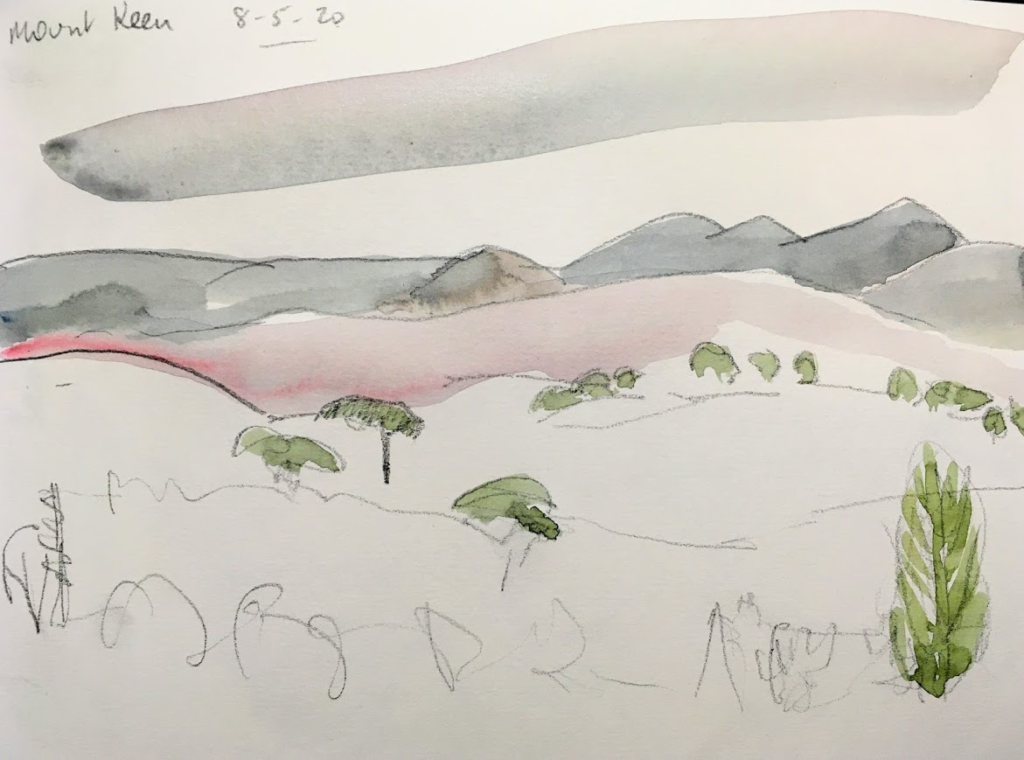

You have been short listed for the Glover Prize on several occasions. Can you explain your work, and a little about the Glover Prize?

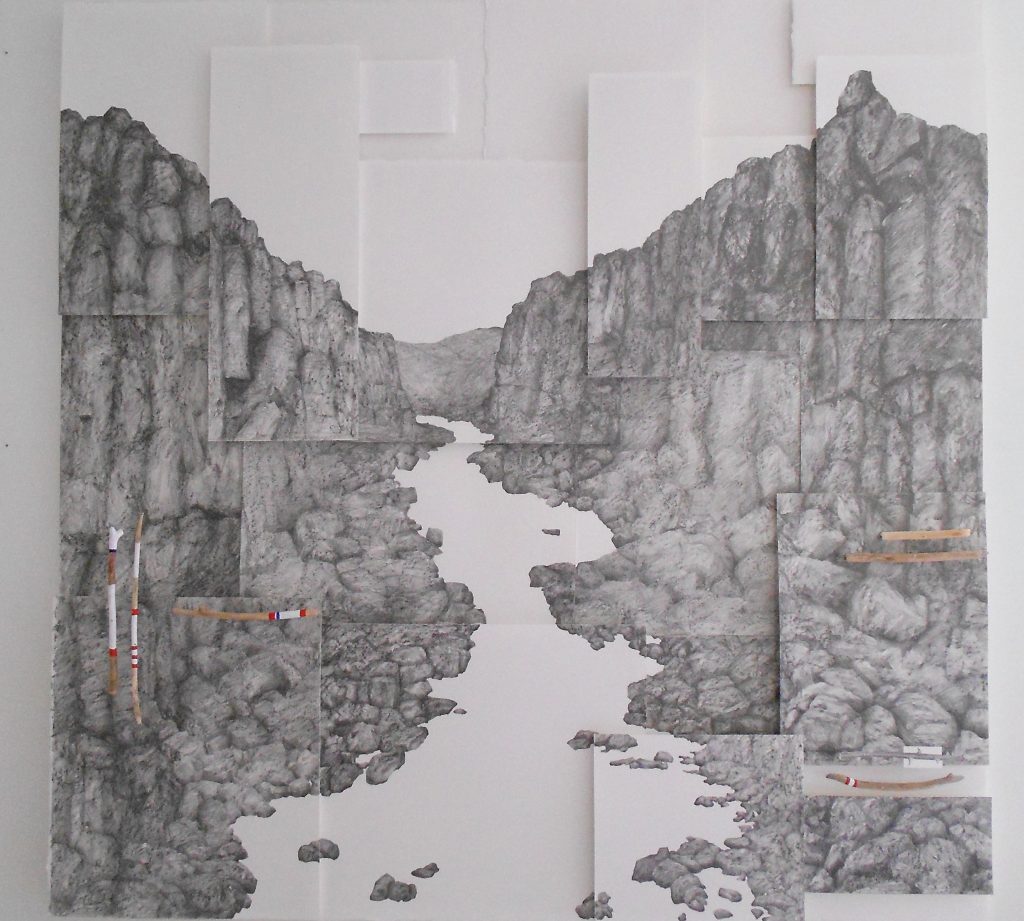

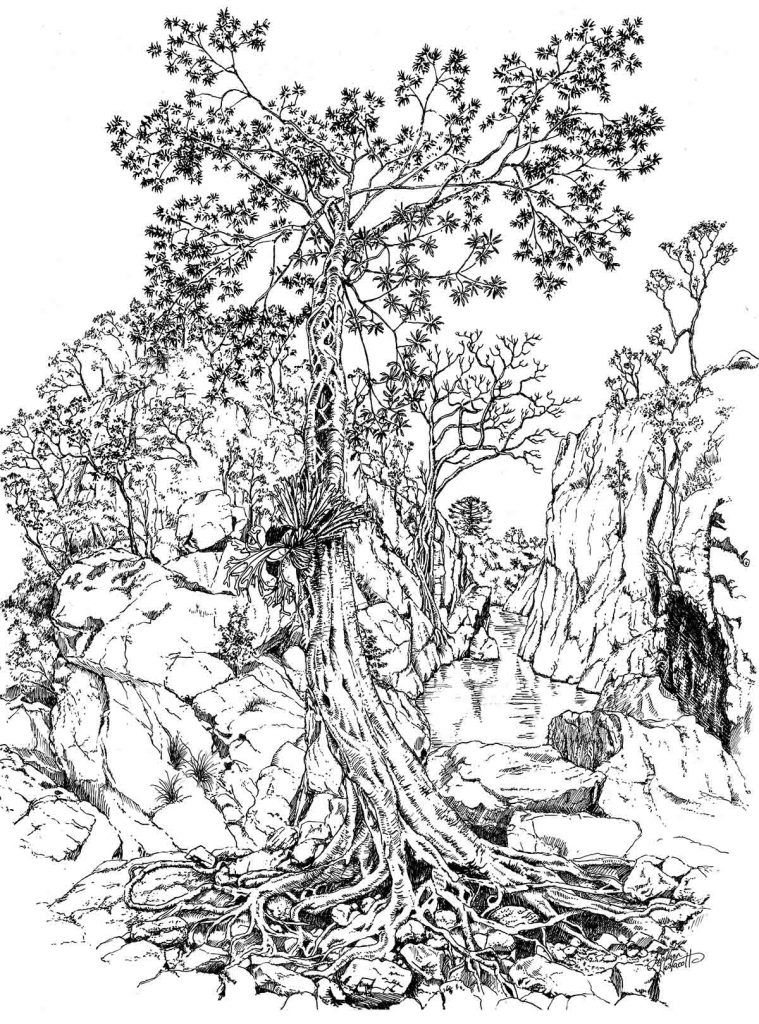

The Glover Prize is a prestigious landscape prize celebrating the Tasmanian landscape. I love being part of this exhibition as it always pushes the question of what constitutes “landscape”. My submissions are always specifically made for the “Glover” and often will examine emotive aspects of experienced memory and place. I grew up in the semi -remote north east of Tasmania and always look back at this time for visual stories to tell.

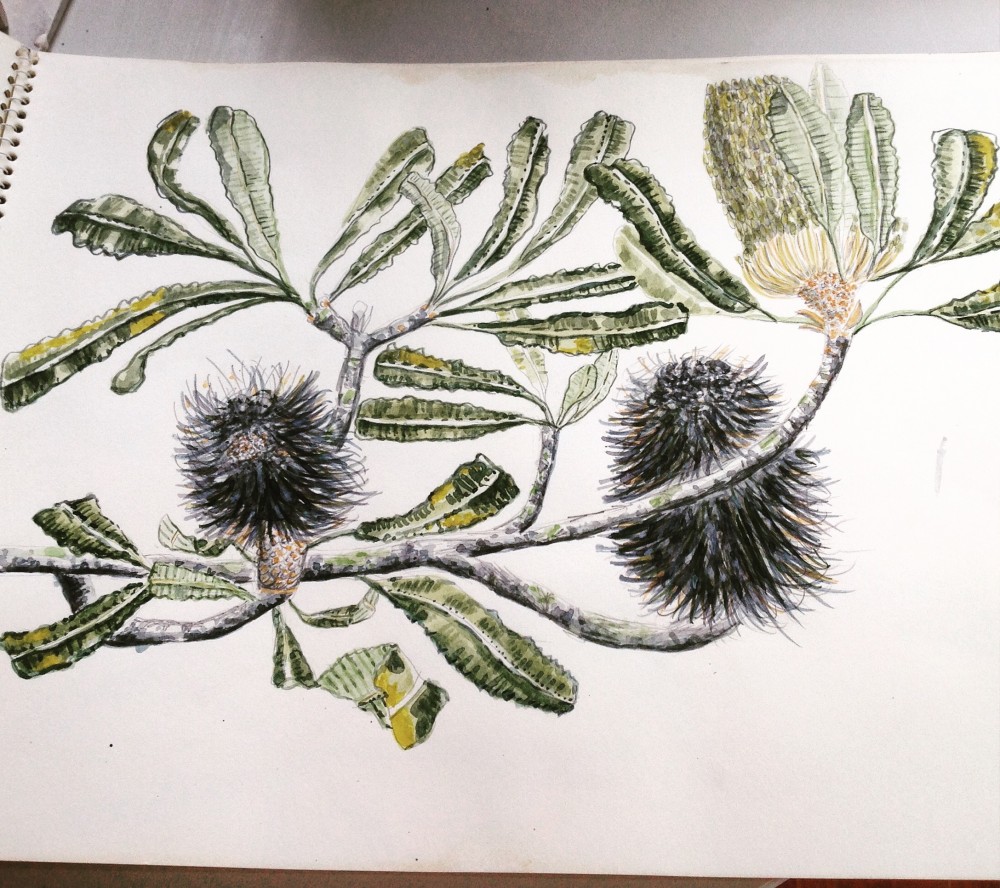

Glover Prize Finalist Drawing “The Gorge in a Hundred Parts

Glover Prize Finalist Drawing “The Gorge in a Hundred Parts

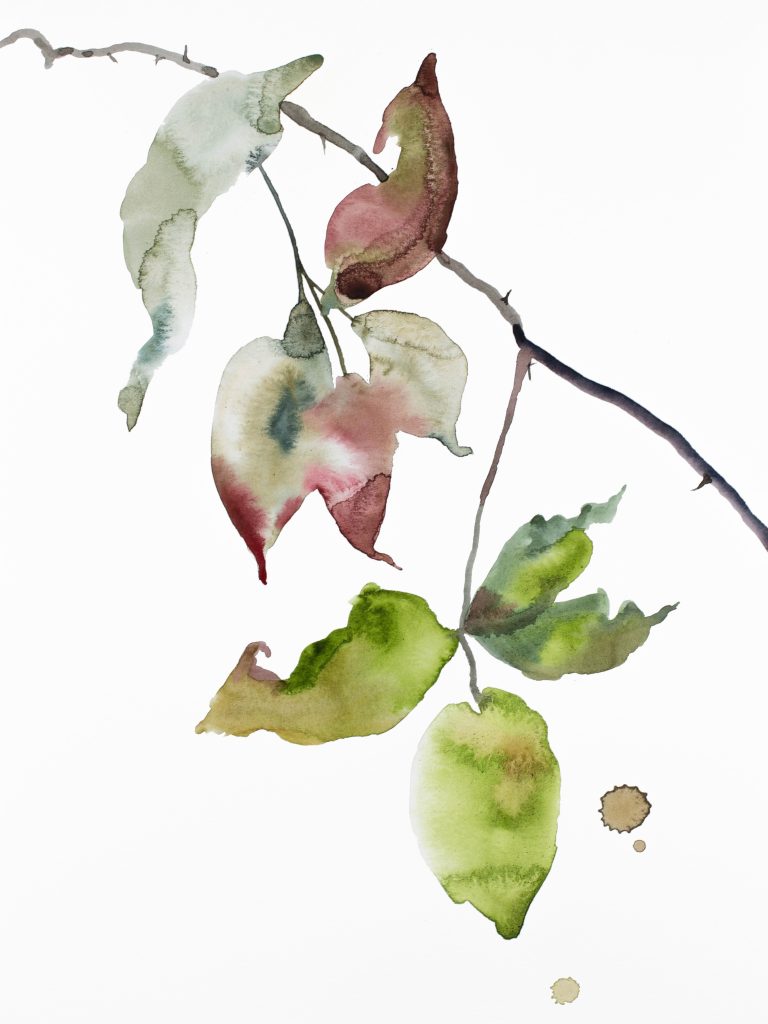

Take ‘Spring Carnival’ and discuss the work and how you combined watercolour and pencil.

“Spring Carnival” Pencil + Watercolour wash

“Spring Carnival” Pencil + Watercolour wash

I have always been interested in the play of known objects and combining additional elements to form another object. In this case it was the “fascinators” worn at spring carnival horse races and connecting the horseshoe as the basis of the headpiece and then attaching abundant native flora to form the fascinator.

Prior to this work I had been producing work only using graphite pencil but wanted to experiment with colour. With great tenacity I started to see how well watercolour and graphite can be combined. This then led to much greater confidence with colour in later work.

The importance of symbolism in this work.

I tend to use symbolism a lot in my work to initially capture the viewers gaze and once I have their attention, I want them to bring them on a journey of storytelling.

In Spring Carnival, the clue was the horseshoe and then it’s not such a leap to start thinking about horse racing, costume and place.

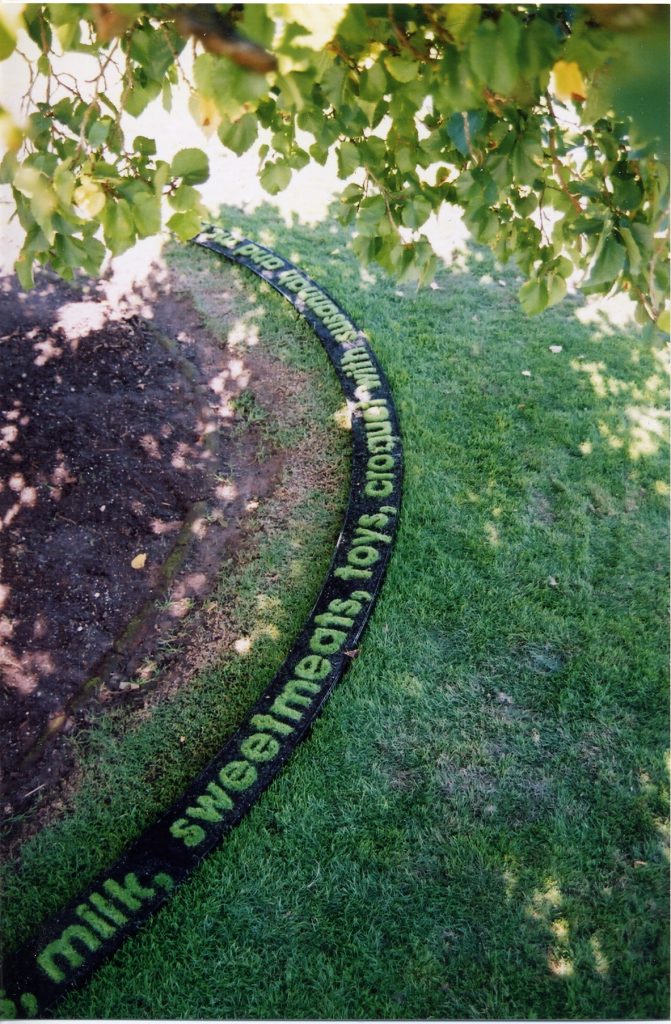

In the “Text Gardens” ie “The Garden of the Lost and Forgotten” superfine grass seed is used to establish the link with colonisation of the Australian landscape.

“The Garden of Human Happiness” grown grass text -detail of cutting. Tasmanian Royal Botanic Gardens.

“The Garden of Human Happiness” grown grass text -detail of cutting. Tasmanian Royal Botanic Gardens.

Comment on the importance of nature in your work.

During Art School I studied as a sculptor and loved the work of site-specific artists such as Richard Long, Rosalie Gascoigne, Andy Goldsworthy, Ken Unsworth, Anthony Prior, among many. All, at that period, were looking at a new approach to what sculpture could be and seemed to enjoy the direct response to a specific landscape.

Coming from a Sculpture department filled with noisy heavy machinery and time-consuming processes, the alure to making ephemeral art installations in the natural landscape was very attractive.

“The Garden of Human Happiness” grown grass text - Tasmanian Royal Botanic Gardens.

“The Garden of Human Happiness” grown grass text - Tasmanian Royal Botanic Gardens.

How have you extended Botanical art to one with your own twist?

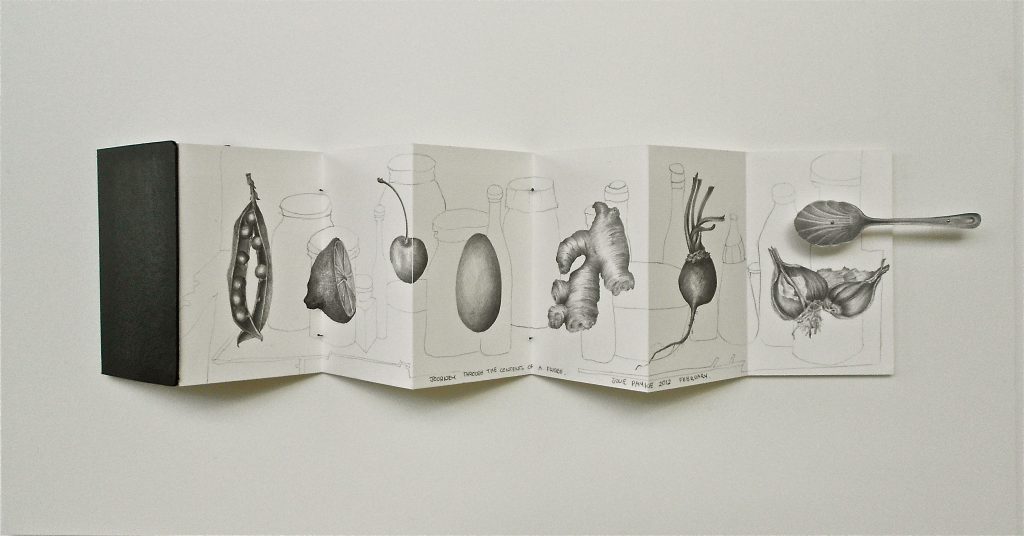

I started looking at botanical art as a return to drawing after studying and practicing architecture. Architecture requires exceptional care in details and botanical drawings worked on a similar level. However, I was not interested in the scientific principles of botanical work and instead used plants as symbols for storytelling. For instance, “Journey through the Contents of a Fridge” was a fun reminder of all the forgotten plants that congregate and form their own colony in unseen human made spots.

How does living in Tasmania influence your art?

After working in Brisbane, Melbourne and Darwin I realised the uniqueness of having a strong family connection to the north-eastern region of lutruwitta/Tasmania.

It was a raw and unprivileged childhood background that allowed immense scope for working out the way of the world on my own terms. It’s also incredibly beautiful place along with being a microcosm of political dissent, tragic colonial history and populated by extraordinary people that seemed to be sifted down to the bottom of Australia. There is plenty to be inspired by in the State.

“Lemon Spritz” Watercolour + Pencil

“Lemon Spritz” Watercolour + Pencil

How does the art society in Tasmania nurture you and your art?

I don’t really have a connection to the Art Society apart from a few workshops to teach form techniques in drawing + colour washes.

Tell us about your studio?

I feel so incredibly lucky to have a studio at the Salamanca Arts Centre on the waterfront of Hobart.

Making art can be a very lonely occupation at times so greeting my studio buddies is a very positive way to start the day.

There are eight individual studios in our section of SAC, each occupied with dedicated professional artists. Although we mostly simply get on with our work after an initial greeting, we do have occasional celebratory gatherings to mark individual achievements. It’s a very positive working environment.

Of course, I could mention that the studio is spacious, light and located in fabulous Salamanca Place but it’s the heartfelt sharing that is number one.

Comment on your series, Flood Sticks, and your environmental presence in Tasmania.

Flood Sticks is a story based in memory and fragility while also showcasing the beauty of the Cataract Gorge in Launceston.

The “Flood Sticks” series focuses on the wildness of the Gorges that geographically divides the city. It is known for their spectacular and dangerous flooding events as well as its calm summer beauty. The sticks have been collected, stripped bare by the raging floods, and juxtaposed with the fragile boat vessels.

“Flood Sticks” Scratchboard + collected flood sticks from Cataract Gorge.

“Flood Sticks” Scratchboard + collected flood sticks from Cataract Gorge.

You use many, different background papers in your work. Comment on this, particularly in relations to ‘IXL Still Life’.

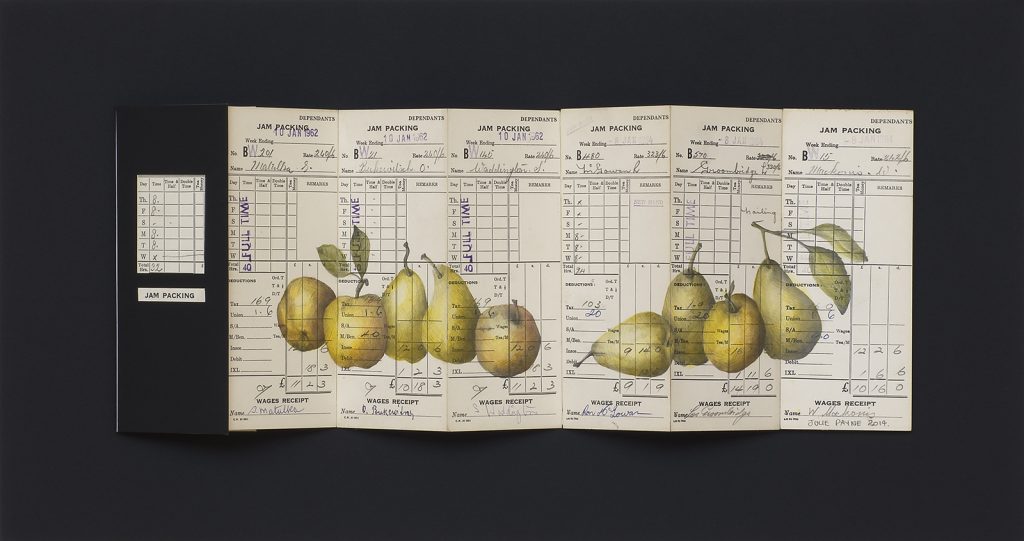

“IXL Still Life” Watercolour and Pencil over salvaged timesheets in concertina format.

“IXL Still Life” Watercolour and Pencil over salvaged timesheets in concertina format.

Experimenting with different papers is similar to a painter experimenting with different “grounds” on a canvas. Each produces a different effect and takes the initial preciousness away from starting a drawing.

In the IXL Still Life series, old timesheets from the Henry Jones IXL Jam Factory were collected, after the site was abandoned, and reused them in a linear format to imbue them with the fruit that was processed on site while also paying homage to the workers.

You have also extended this by putting your work in a book format, comment.

“Journey through the Contents of a Fridge” pencil on paper.

“Journey through the Contents of a Fridge” pencil on paper.

The concertina book format was chosen to suggest a processing line and telling longer individual stories.

Discuss the use of humour in your work.

Along with tackling many political and emotive themes, I do enjoy a laugh as well.

“The Culinary Greens” Graphite and coloured pencils.

“The Culinary Greens” Graphite and coloured pencils.

“The Culinary Greens” started as an exercise in using luscious, coloured pencils. It soon developed into a story of eating your greens and different families of vegetables. I saw the Culinary Greens as the apex family that everyone aspires to.

Beyond your studio, into gardens. How did this become such a large part of your art practice?

In 2001 I was commissioned to produce artwork to celebrate the opening of the Queen Victoria Museum, Inveresk site in Launceston. It was a disused railway yard employing hundreds of workers during its days. The Museum restoration had sanitised the huge site, eliminating the personal histories of tendered gardens and social gatherings that occurred. I liked to think that no matter how much new landscaping had been done, the tender history of site would always seep through and start telling stories. This is where the idea of growing text that suggested past activities originated. It was called “The Garden of the Lost and Forgotten” and I loved that you could not supress history so easily. It was also delightful tending this garden. It’s certainly high maintenance.

Garden of Loss and Desire” grown grass text - detail. Woolmers Estate

Garden of Loss and Desire” grown grass text - detail. Woolmers Estate

However, the process, the stories that could be told, and the clean visual impact was very satisfying and I went on to grow another four text gardens commissioned for various festivals.

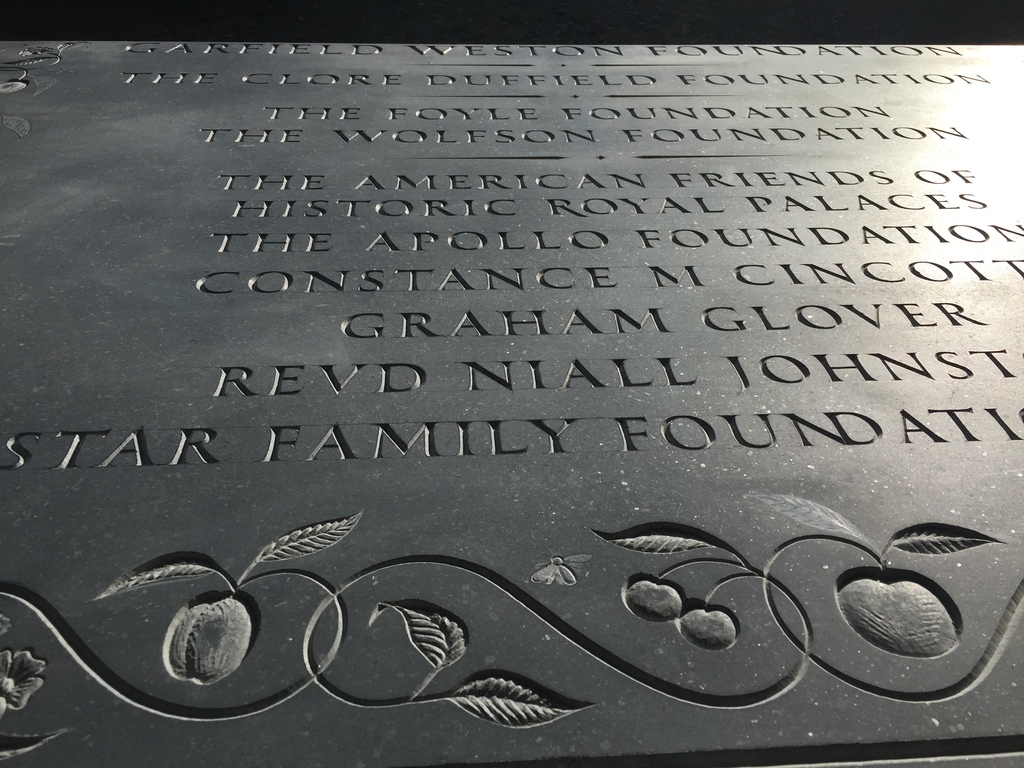

Explain your commission within the Conservatory at the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens?

“The Garden of Human Happiness” was grown specifically to tell a wandering story around the fountain within the Conservatory of the Royal Botanic Gardens.

“The Garden of Human Happiness” grown grass text - Tasmanian Royal Botanic Gardens.

“The Garden of Human Happiness” grown grass text - Tasmanian Royal Botanic Gardens.

What other installations have you done?

Other site specific Installations have been created for Woolmers Estate, Festivale in Launceston, and Kelly’s Garden in Salamanca Place, Hobart.

“Mr Peacocks Garden” grown grass text. Salamanca Arts Centre Hobart, Tasmania.

“Mr Peacocks Garden” grown grass text. Salamanca Arts Centre Hobart, Tasmania.

Ephemeral works locations have been located at the Cataract Gorge, Launceston; Fortescue Bay, Tasman Peninsula; Port Arthur Historic Site and Holly Bank Reserve.

How important is the weather for your installations?

A good downpour of rain is always welcome, although this often means a brisk growing session and lots of hand trimming with scissors. Gardens are always germinated in controlled greenhouse conditions until the words are stable enough for an outdoor location.

Does this art need both ‘Green Thumbs’ and tender loving care?

The art of Sculpture requires an artist to be a master of many crafts. One simply has to learn the craft and limitations of the material for each idea. Growing grass in the form of Helvetica Bold is no different.

"Topiary Ted" sewn fake grass topiary

How did ‘Topiary Ted’ come to life?

“Topiary Ted” was a response to a group exhibition at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Tasmania. I thought it would be fun to upset the formalised gardens layout with some more unusual topiary. Obviously, I didn’t have the time to grow real topiary, so recycled tennis court Astro turf was sewn together to bring Ted into being.

Ted was greatly loved, and I certainly learned the residual power of the childhood teddy bear on visitors.

Astro turf, fishing line and recycled plastic bags never seems to die, so three Teds now sit watchfully in my own garden.

Discuss Tasmanian history and your art?

There is plenty of Tasmanian history to examine and make comment on.

Tasmania has a history that is both culturally rich and, at times, devastatingly cruel and unequal.

Issues ranging from the in just treatment of the Palawa people and convict servitude to the privileged dominated the colonial times.

Relatively recent issues of deforestation, invasive species, environmental and social issues, and loss and memory have all been foundation ideas for various artworks.

Explain your involvement lecturing at the University of Tasmania.

Teaching at the University of Tasmania was a delight. After graduating in Architecture, I was asked to lecture three days a week in Foundation Studies with first year students.

In the second year of teaching at the School of Architecture, the School of Art invited me to teach Sculpture for the remaining two days available.

Although it was a bit crazy sometimes figuring out which school a student was in if I saw them out of context, I thoroughly enjoyed each and every student, yep, even the ratbag ones.

Teaching Sculpture at the School of Art taught me to quickly identify where a student was trying to head with an idea and hopefully assist with being able to distil the concepts’ essential qualities.

Teaching in the School of Architecture was a revision of the complex interplay of ideas, research, practicalities and building skills to think and draw three dimensionally.

You are busy doing residencies, take one that has led you to relook at your work.

I have been fortunate to be granted three studio residencies in France and Ireland. Each have had a positive impact in disrupting patterns of working but it was at Draw International in Caylus, France that was the most enjoyable. The quality of the participants is high, I thoroughly enjoyed discussing ideas, trying new less precious techniques and living in a small French community.

Studio at Draw International - Caylus, France

Studio at Draw International - Caylus, France

Contact:

Julie Payne

Details

Julie Payne

Tasmania, Australia

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April 2024

Images on this page are all rights reserved by Julie Payne

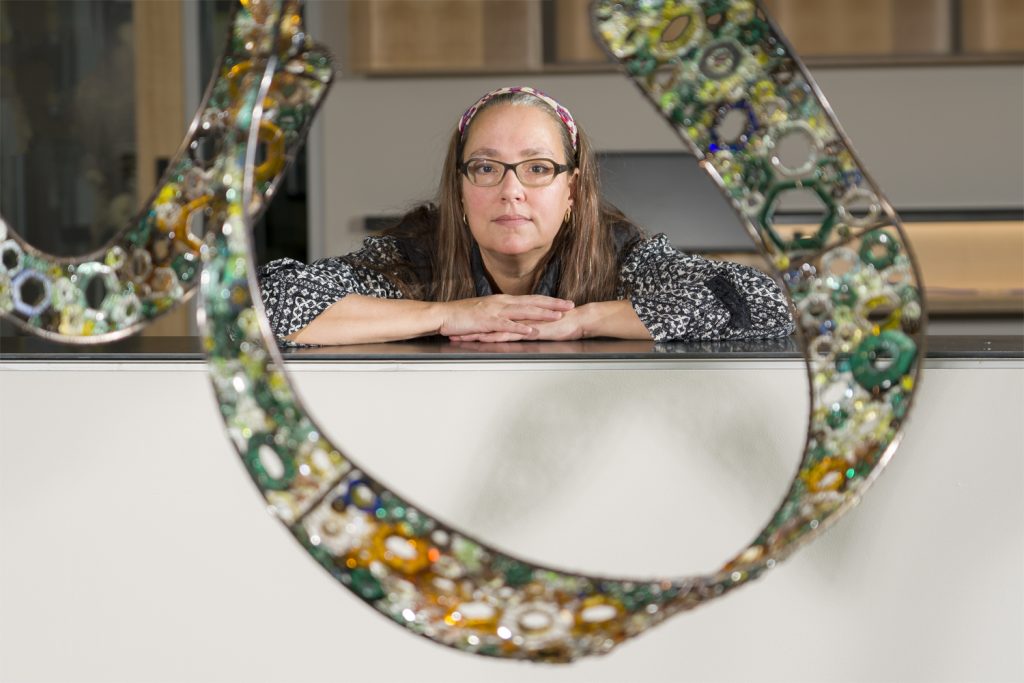

Jerusha McDowell

What led you to open a Gallery and go beyond being a freelance photographer?

I studied photography and filmmaking at university and returned to photography following a very different career. I made the decision about two years ago to resign from my career in the Defence and Intelligence community to focus on photography as a full time career.

I opened the gallery exactly one year later, and it has been open now for a year. When I first returned to photography I began working as a freelance photographer doing equestrian events, and client work but I was always very focussed on developing my core landscape and documentary work and opening the gallery seemed the logical next step. There is something special about exhibiting your work the way it is meant to be experienced. The digital world is so vast these days it is easy for photographers to get their work seen without the need to print and frame and present the work. But to me a photograph isn’t really a photograph until it is printed. A photograph has such a journey from the decisions you make taking it, through the editing process, to the printing, framing, and exhibiting. The gallery is very important to me because it allows my work to reach that destination.

Added to this you are also a film maker. Tell us about this part of your professional life.

I studied both photography and film making at university, and I have always loved video and film making. I am getting the chance to do more film and video lately and I’m really enjoying it again. There will be a film component to the project I am working on in the Mountains. Right now, we’re just working through some of the logistics issues of carrying video equipment on horses.

Take us to ‘Your Australia’ through e crossing.

The Crossing is the first collection from a documentary project I am working on titled ‘Where the Snowy Mountain Stockmen Used To Ride’, photographing riding expeditions in the Australian Snowy Mountains. This is an ongoing documentary project with my friend, guide, and subject Mark Swan. It began simply, as an excuse to ride horses and shoot remote and beautiful landscapes.

It quickly became something much more. ‘The Crossing’ collection shows a plateau crossing in bad weather near Tabletop Creek in the Snowy Mountains, and simple fireside rituals as we stop to rest and let the weather clear. Photography is about more than pictures. it’s about revealing things unseen. It’s about showing people something through your eyes. As a photographer your connection to a subject is the defining characteristic of storytelling.

The weather up here changes so quickly, changing the entire landscape around you. The fog had closed in, blanketing the landscape, and making navigation uncertain. The wind and rain were driving in hard making lighting a fire seemingly impossible, and yet, with a little patience the quart pots were soon filled with hot tea. This project continues to be an amazing journey. Getting to capture the amazing people and places out here is one of the great privileges of my life.

I have been overwhelmed with how this project has been received so far, it has been published in RM Williams Outback Magazine and has received a number of awards including a Top 5 in the International Photography Awards. Shooting in the mountains is never easy. The weather changes so quickly around you. The riding is hard, the environment harsh and unforgiving especially on sensitive camera equipment. But as an artist these are the projects you dream about.

Discuss the pleasure of cropping and highlighting images? E.g. ‘Buckled’

The editing process is interesting, I never really sit down with an image and know exactly where I’m going. I feel like every image has its own journey that it takes me on, not the other way around. The decisions you make when editing in photography are usually about what to leave out rather than what if anything you add. Cropping can change the whole story quickly by removing the clutter and distraction around an element you are focussed on. Buckled is a really good example of this. Where focussing on a much smaller part of the scene tells a more potent story.

Comment about the importance of limited editions of your photographs?

Doing limited editions is something that was a natural progression after I opened the gallery. It reinforces that the photographs are a finite physical thing. This is really important in the modern/digital world I think.

Also, smaller purchases, cards, and the sold-out calendar for 2024.

The gallery offers selection of fine art landscape documentary works as well as a range of cards and giftware.

HORSES…

Tell us about your love of horses, which is so obvious in your work.

Horses are definitely a lifelong love affair, and one I am now lucky enough to share with my daughters. Horses force you to be honest, not just with them and with yourself. Otherwise, they see right through you. I am incredibly lucky now to be able to combine my love of horses, the bush, photography and storytelling in the one creative pursuit, and it feels like coming home. Photography teaches you many things, patience, the art of observation and above all perspective. You understand the power of perspective and your ability to change it. Photography and horses have been such an important anchor for me since leaving my national security career. The discipline and solitude of it has given me the space I needed to recalibrate.

Take one or two equine images and give us a short inside story that goes with the photograph.

This shot is special and is probably a good example of how I moved from shooting events to shooting in a more documentary style. I now think of almost all my work as documentary photography. It is documenting people, horses, landscapes in a way that shares the world around me with the rest of the world. This image was taken at local horse event, but I was more interested in what was happening out of the arena. This was an incredibly tender moment as the rain began to fall Phil responded to his horse’s gesture, walking over and allowing a moment of connection which I was lucky enough to capture. I remember his response to the image was quite emotional.

LANDSCAPES…

To me landscape photography isn’t about a perfect image. To me photography is all about storytelling, if there isn’t a story, it doesn’t matter how perfect the shot is, it isn’t going to resonate with people. I am attracted to telling stories that help me tell mine, that reflect my search for identity and place. I like creating images that have a certain amount of ambiguity to them. That are more a question than an answer. I began life on a very remote property in the bush, in the high country of the New England Tablelands. We had no electricity, no plumbing, and for me life unfolded beyond the reach of the modern world. My earliest memories are of the rhythms of the bush, storms rising, up through the gorges, the smell of horses, eucalyptus, kerosine and woodsmoke in the rain. It was a magic place that had a deep and lasting effect on me. A tension between the desire to live outside the safety, comfort and complexity of the modern world and the deep yearning to belong somewhere has always pulled at me, is a recurring theme in my work.

Comment on the almost sepia colour of your part of Australia in photography.

I guess That’s a question of style and I guess I definitely have a style or a signature, especially in the tones and colour I use. I used to work overseas a lot and coming home after being away a while was always emotional. I’d flick through inflight magazines featuring the familiar Australian landscapes, grateful to be home, grateful to be whole, and returning to our beautiful land. Yet I always found myself searching in vein for my landscapes. The glossy spreads would feature the red dirt of the interior or the sapphire blues of the coastline but not the beautiful soft tones of the middle; the tablelands and high country. This is my country. The colours and contours of these landscapes have a unique beauty. Harsh and yet soft and subtle. The light, the sky the air. Over the range but not out back. These are the landscapes I love. I think if I have a signature or style it is because these are the colours and textures I love, that comfort me, that call me home. I was asked recently how long it took to develop my style… I hope, is a lifelong journey. It takes a while for you to start trusting your own instincts and stop looking to emulate others but once you do it’s a never ending process of discovery and expression and evolution. So many things influence and change you and you always keep learning and growing. Creativity is a strange unaccountable thing.

The physical vastness and what you are wanting to capture and why? I approach landscape photography from a feeling or emotion. Its about using elements in the landscape to tell a story or express something. It’s usually more about what a place feels like to me rather than what it looks like. It’s funny, I still don’t really think of myself as a real landscape photographer even though I take a lot of pictures of landscapes! My most recent landscape collection ‘Fields Of Gold’ is a series celebrating the vast beauty of the snowy mountain high plains and the brumbies that call them home. Influenced by the early Australian impressionist paintings that always captured my imagination, these works to me are about capturing the freedom and promise of these these plains.

Can you expand on the importance of your skill within your rural community?

I am a part of an beautiful rural community here in Bungendore on the NSW Southern Tablelands. One that has given me friendships and creative partnerships with incredible people who inspire me endlessly.

My gallery is part of The Malbon, an incredible local business collective which includes local businesses and artisans its been such a huge opportunity for me to grow by business and expand my reach as an artist, and I have also been able to use my skills to support growth and evolution of the Malbon its a great partnership I am lucky to be part of an amazing and supportive rural community here in Bungendore.

I love this landscape here. Not the white-sand beaches of the coast not the red dust of the outback. I love the crisp air and muted colours up here, it’s harsh but it’s subtle and beautiful too.

Contact:

Jerusha McDowell

Details

Jerusha McDowell

Rushe Photography Gallery open 7 days, Bungendore, NSW

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, March 2024

Images on this page are all rights reserved by Jerusha McDowell

Jacob Barfield

Comment on your statement, ‘Piecing the puzzle of life together through art and creativity.’

This statement is something I created to describe the feeling I felt when starting to try to make a career as an artist. It’s confusing like a puzzle, but if you stick with it and don’t give up eventually you’ll be able to piece it together.

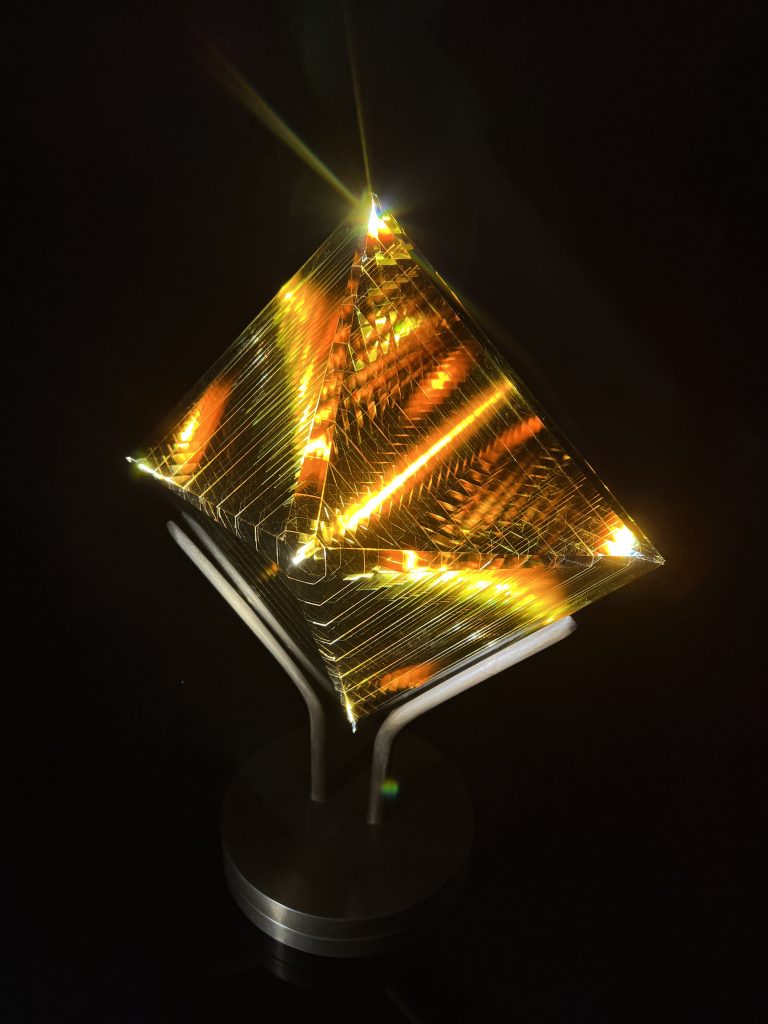

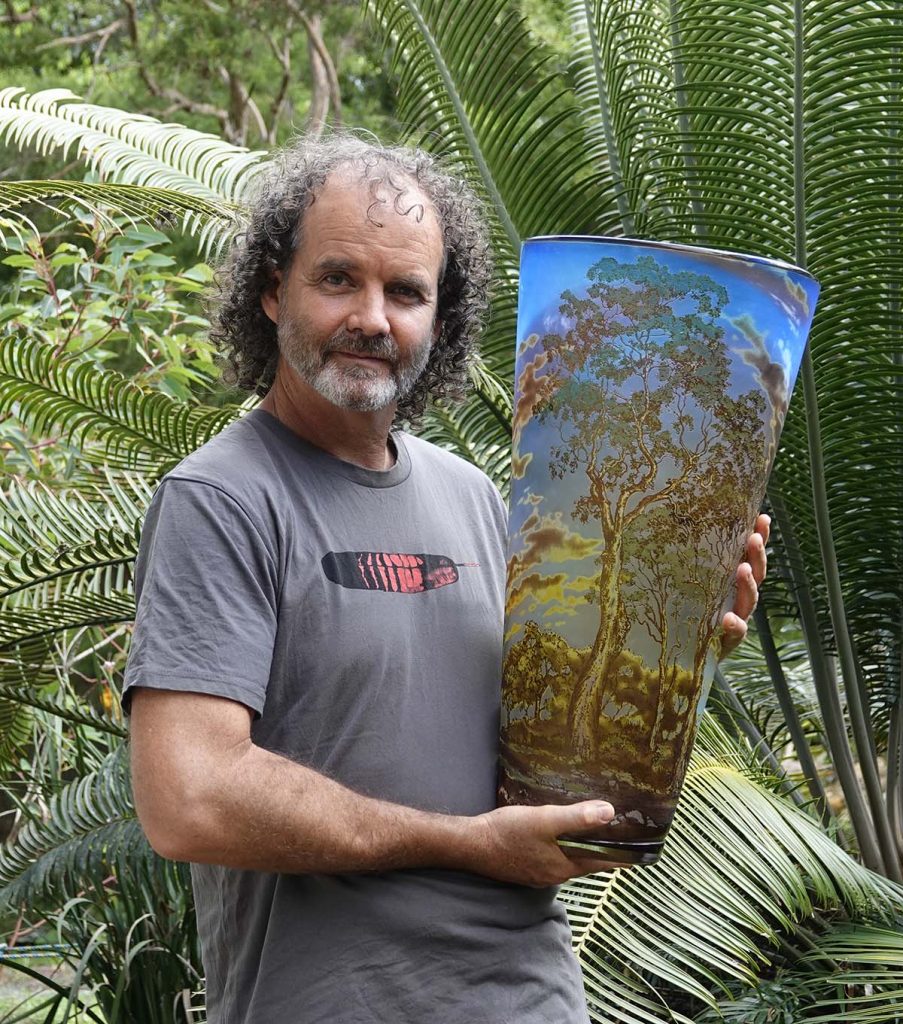

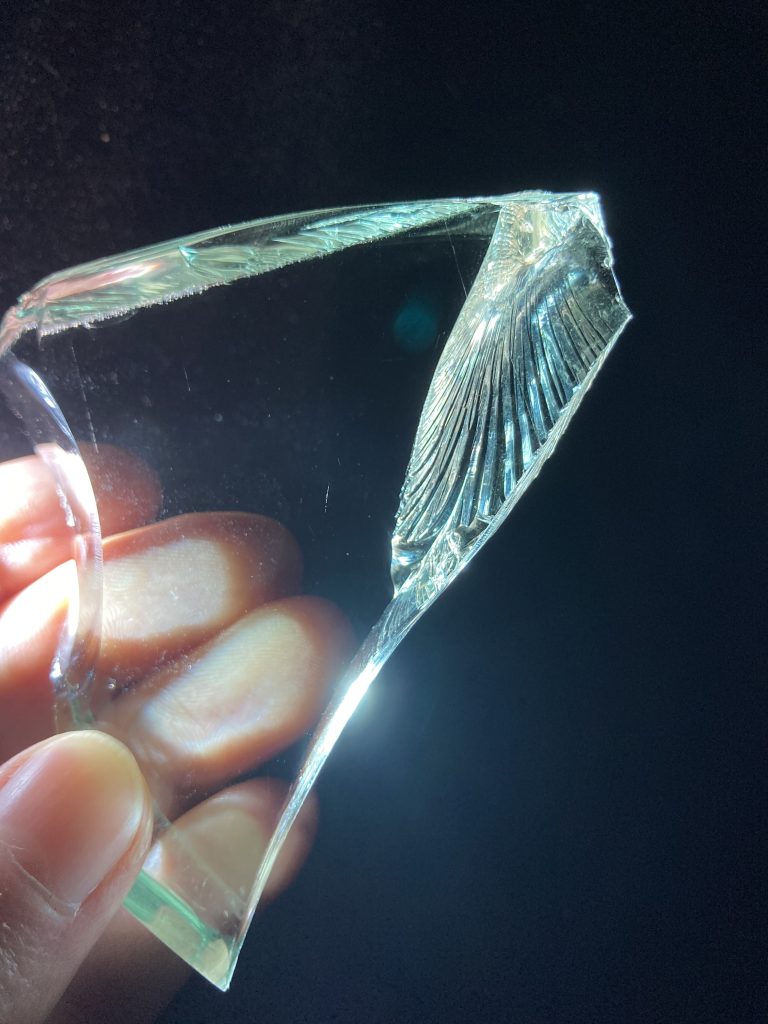

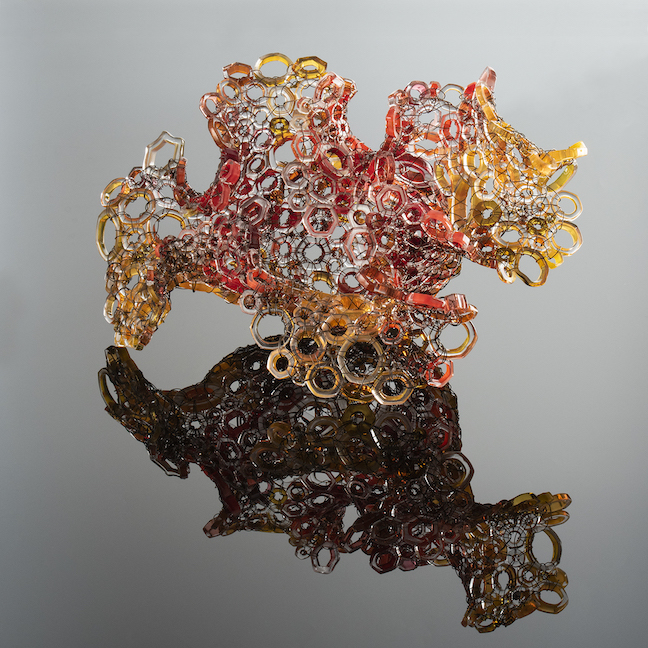

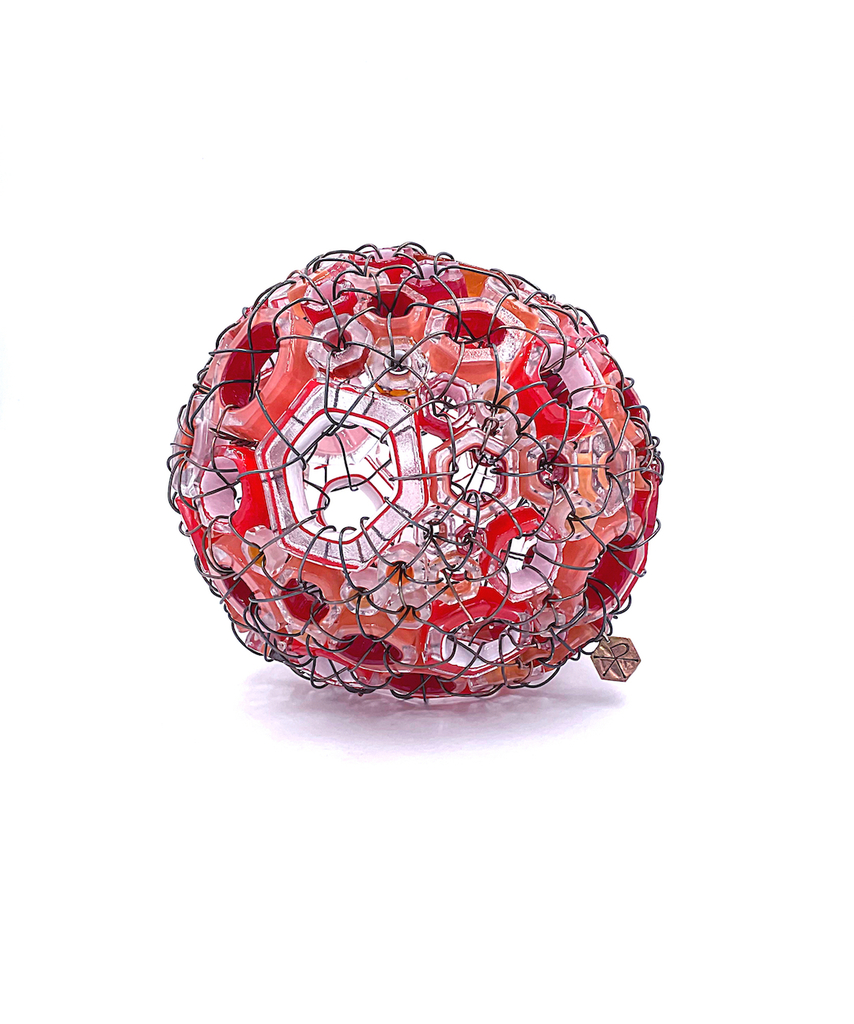

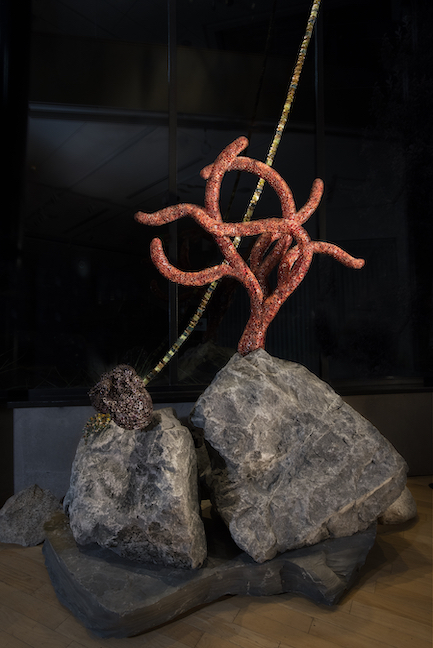

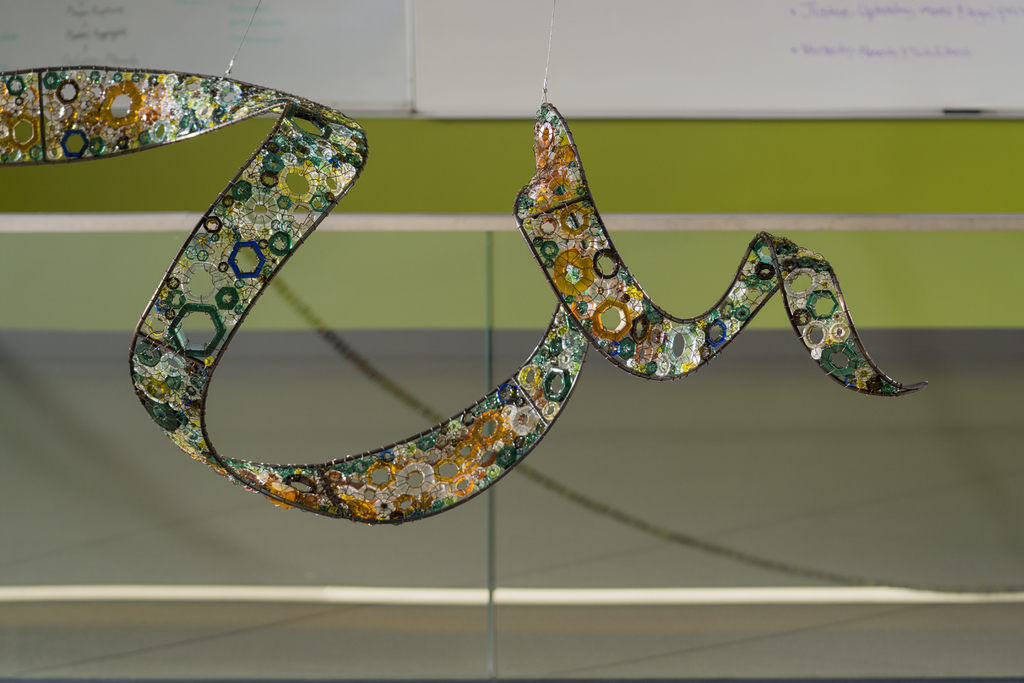

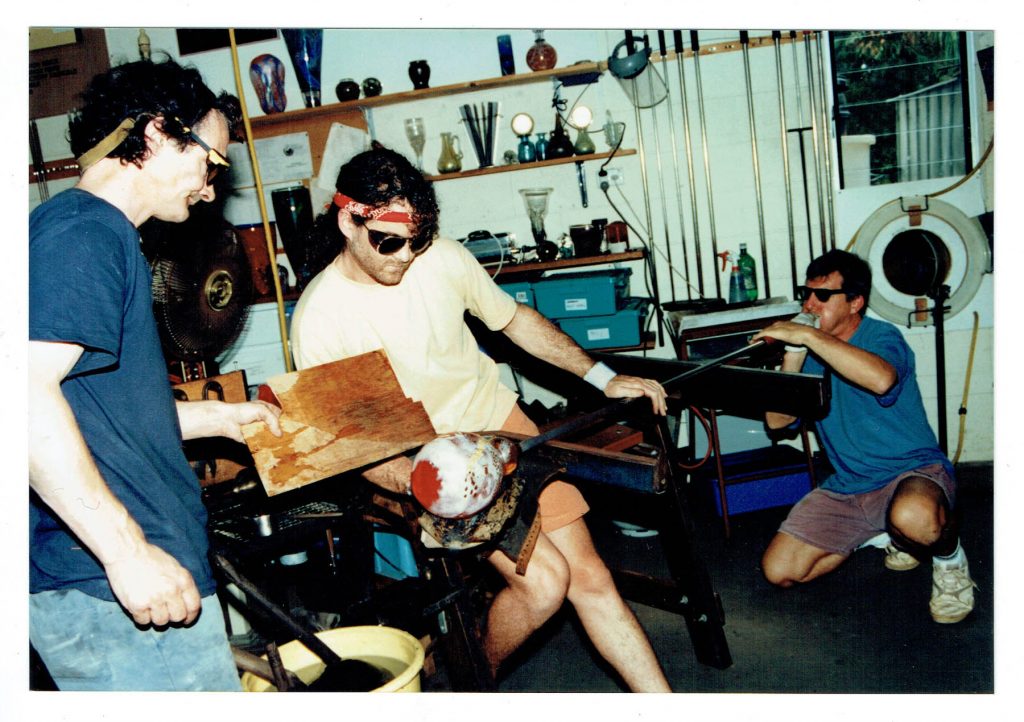

How do you develop both Glass and custom-made metal stands. Combining two very different skills?

Learning how to work with metal was a skill I learned out of necessity to take my art to the next level. A lot of glass art needs to be displayed in certain ways in order to get the best effect. Metal stands are not only strong but when done properly complement the artwork. Most of the time I develop the artwork first and then design the stand around the piece.

Discuss how important it was for you to shown technical skills as a young boy.

Learning how to work with my hands were very important skills to develop. Almost every job and hobby I had required some sort of hands-on skills that took time and practice to develop. A lot of those technical skills required good hand-eye co-ordination, I was able to translate that developed coordination into the work I currently produce.

Comment on how you see art as a continuum to your art skills.

I’ve always enjoyed learning new things and one of the qualities of glass that I enjoy is how many tools and skills are required when producing the art. Because of this I had to learn a large variety of new techniques in order to produce the work I wanted to make.

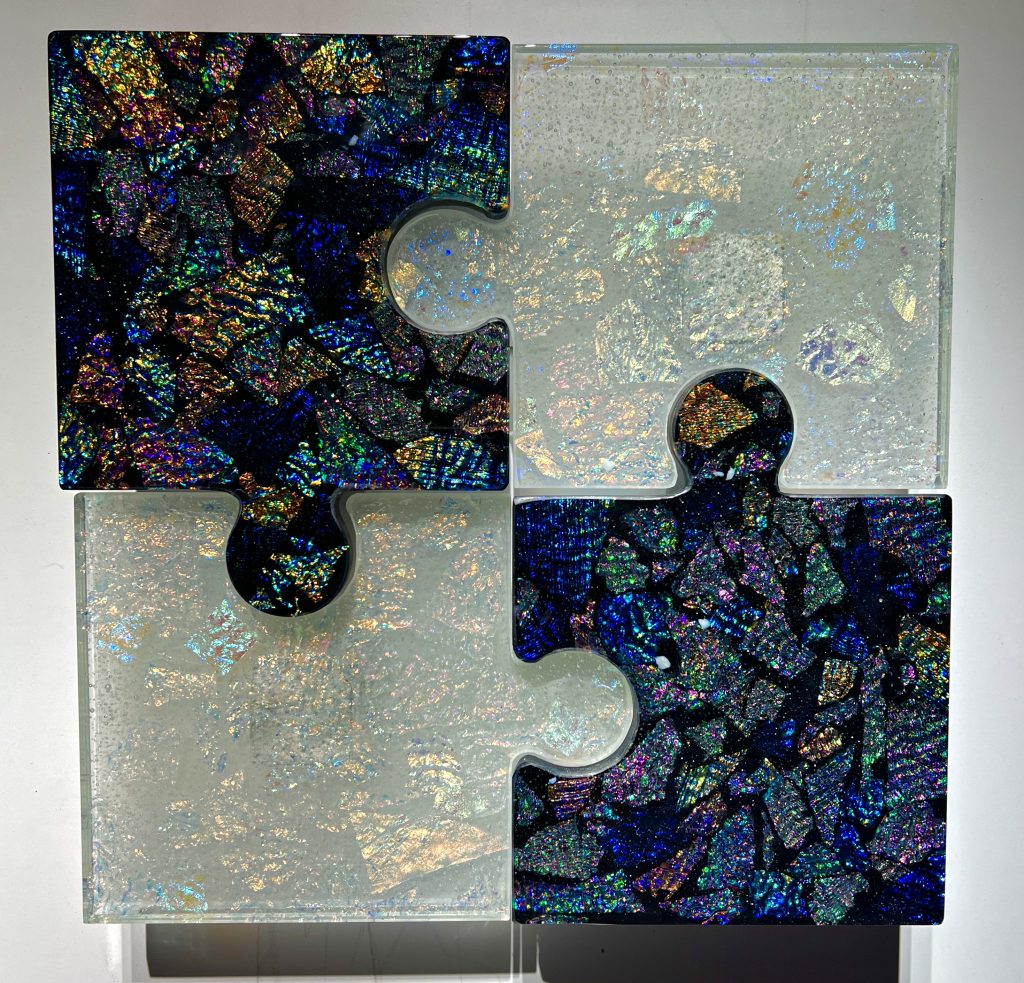

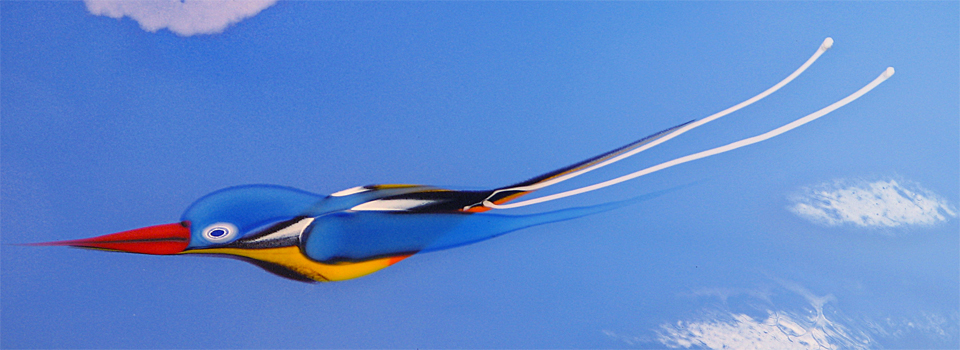

Puzzle Pieces.

Where did the idea come from?

I’ve always liked puzzles and I even made a puzzle piece table in woodshop class in high-school.

So I guess the idea of puzzle pieces as artworks was always in the back of my mind. But when I started to pursue glass, I wanted to produce something that had a lot of versatility. After dwelling on the idea of versatility for a while I eventually thought back to that project in high-school and decided to try making puzzle pieces out of glass.

Can you briefly explain the production of this series?

The pieces are made by taking chunks of glass and melting them into a puzzle piece shaped Mold. Once cooled down I then coldwork the edges so there aren't any sharp edges. Then I polish the glass and attach custom made mounts.

How large are the pieces?

The smallest is 8 ½” the largest is 13”

How are they sold? (the number of interlocking pieces)

They can be sold individually or in complete sets.

Comment on diverse ways the pieces can be displayed.

All the pieces are designed to connect with one another. You can assemble a collection in any way you want. These pieces can be mounted on the wall or attached to a stand and displayed on a table.

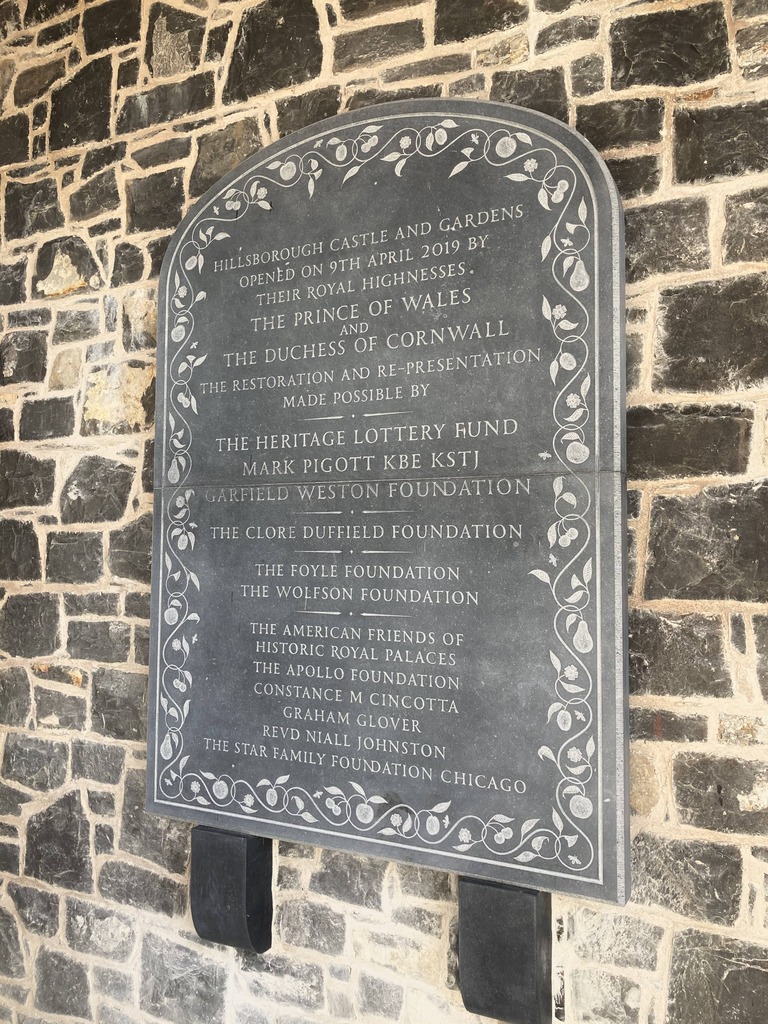

What and why are there restrictions on the size?