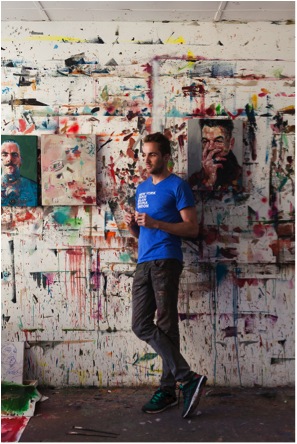

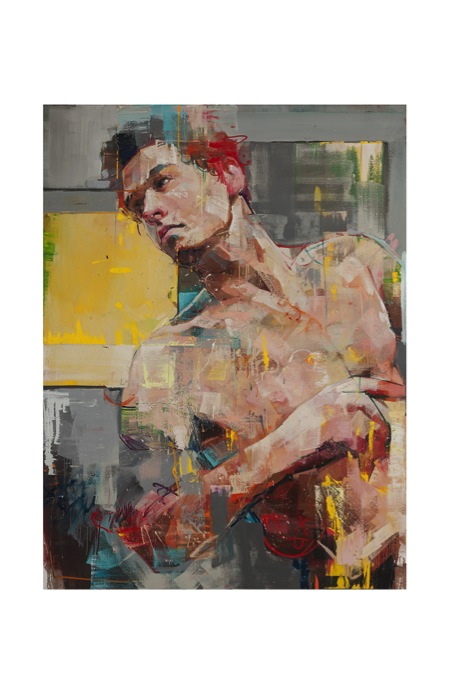

Andrew Salgado Painter - London, UK

The size and scale of your images is huge. How do you physically cope with this aspect of your work?

One of my favourite painters is Daniel* Richter, and I recall as a student artist at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada) being familiar with his work but being rather ambivalent about it; one day I saw an exhibition of his paintings at Helen and Morris Belkin gallery on campus, and I was completely blown away by the monumental scale of the paintings. As a young painter, it was a cathartic moment; one of those rare shows that not only asks you to rethink the work of the artist in question, but rethink how you consider painting as a whole.

For me, scale is an important aspect of the identity I have forged for myself as a painter. I have to remind myself to hold back sometimes, and challenge myself to work on a smaller scale. My last solo exhibition (Variations on a Theme, NYC) purposely included very large work as contrasted by very small work. I like what this polarity suggests, and for me, it’s the mid-range pieces that are almost irrelevant. If it weren’t for the limitations of my studio (ceiling height and the logistics of getting work in and out) I think I would like to even go bigger.

There’s a certain power with scale, and the freedom to move about and explore the canvas, where your brushwork actually becomes a record of movement in time and space. I am drawn to the grandeur of scale, the suggestions where a torso becomes twice the size that it should be; it is almost a sublime experience looking at a figure that is unnaturally large.

Conversely, I find small paintings challenging because it’s easy to be ‘important’ on such a large scale, but it is difficult to make a bold statement when you’re working with such confines. I also notice that I become a very different painter when I work small-scale, but that’s to be expected.

Big, Bold, and Brash is the feeling I get when viewing your work, is this your aim?

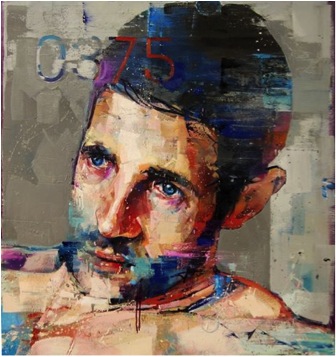

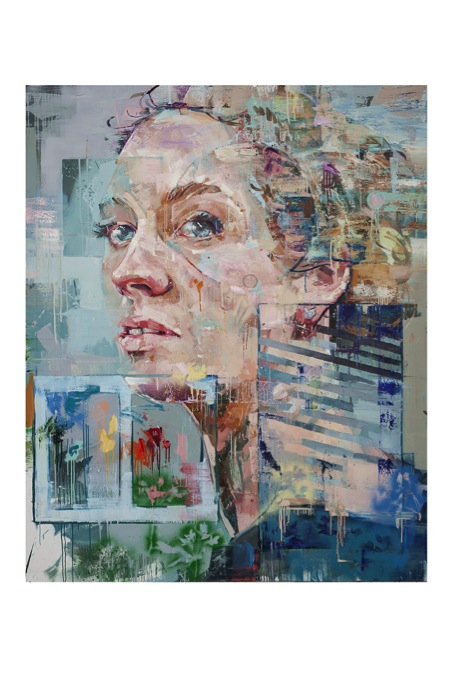

I’m not sure that brash is a good thing. To me, it seems like a cheap trick. I think there’s a confidence in the new work, and a freshness that I’ve earned as I mature as a painter. The work also comes from a politicized source. As a gay male and a victim of hate-crime, the work has a message that goes beyond big-for-big’s-sake. The work is aggressive because it is asking the viewer to consider and challenge something beyond what is immediately visible. I know a lot of big, bold, and brash artists but to me these adjectives recall something almost pejorative: like a big tacky sign. I like to challenge myself and my viewer, and I don’t like to make work that sits comfortably; something is always off-kilter, waiting to be deciphered. I do think from time to time the work is bombastic, but with each successive body of work I tend to focus on an adjective that subconsciously comes up and guides me. For my Cape Town exhibition it was ‘intimate’. For NYC it was ‘purposeful’. And for London (opening October 4th at Beers Contemporary) it’s ‘deceptively simple’. So I think for many painters it can be quite easy to pull off ‘big’ and ‘brash’, and I think it is challenging to be subversive when you’re playing with scale and aggressive, politicized themes. I also think the work is changing, rapidly, and markedly. On one level I’m still the same painter that I was before, but on another level, I’m entirely not the same painter that I was before.

You use many mediums as well as oil, spray paint, collage, text, and video discuss how you know when to stop?

There was a foray into video during my Masters at Chelsea College in London in 2008, spurred by necessity as a result of insufficient studio space and a (painter turned performance artist as the) course Director who tried telling me I was a performer and not a painter. However, even those videos were ultimately all about paint. When I left the degree I also returned to painting, which is really where my love-affair lies.

Everything else has been quite causal. I believe in being informed by your immediate surroundings. After a particular commission I was erroneously given a box of spray paints; they stared at me in the studio for some time until I thought ‘screw it’ and began incorporating them into the work. However, their use is always quite subversive. Spray paint has this tendency to be a very immediate, very loud media, but I use them in a method where they’re almost indecipherable. This to me is almost a form of trickery; the viewer is pulled right into the piece – endlessly looking. Earlier this year I began using them to stencil the my materials onto the piece – the silhouette of a brush or a palette knife, for instance; and eventually this evolved into actually sticking the actual object onto the canvas in its entirety. Sort of a self-referential act, where I’m constantly trying to remind the viewer that this is a reconstruction, a creation, there was a process involved, a fiction… I like to draw attention to my materials and this was just an evolutionary step, it was never intentional, it just happened.

If it becomes a gimmick – then so to do the paintings – and it is funny, because my most recent work has pulled back entirely…they’re only oil on canvas again. I’ve retreated back into the cave, just me and brush, but I still have some tricks up my sleeve.

How do I know when to stop? You have to listen to the intuition because you can’t pull out to early, either. But for every successful painting there’s probably a failed idea or unfinished work somewhere as well.

You make the comment, “my studio is my paradise and my prison”. Can you expand on this?

Art is a give and take exercise. As artists we play with fire, and from time to time you risk getting burned. I think as artists we need to know when to ‘cool it’, and step away from the work altogether. We need that impetus to create, and sometimes it’s simply ‘not there’. I work alone, usually 6 days a week, at least 8 hours a day. If you’re not careful, this creative space can become a draining space. But there’s nothing quite like that feeling when you’re in the studio, and everything seems to ‘click’ and you surprise even yourself. However as artists we need the crises, the failures; they are what help us grow and learn and improve.

Your exhibition in NYC was a sell-out – Discuss how and why your work relates so well to NYC?

I don’t think its NYC in particular that my work relates well to…I would like to think it has an appeal that transcends any particular location. I’m Canadian, half Mexican, but I live in London. So I’m a bit of a mixed bag myself. In fact my last 6 exhibitions were all sell-outs, which is amazing, but also brings with it a new series of anxieties. There is a demand now for me to constantly trump myself: each show has to be better; the work more important; and of course we don’t want the ‘winning streak’ to end. So that’s definitely a pressure for me but I try not to think about these things because the real importance is the paintings. If the paintings are spectacular, everything else will fall into place. I broke through a glass-ceiling with the paintings for the NYC show, and as an artist it’s an incredible feeling to surprise even yourself. The paintings were sharp, and fresh, and crazy, and I do think that a NYC audience responded to their immediacy. I’m hopeful, as well, because the initial paintings for the London show are off to a promising start. There’s another change, and the works are a little more complex but also a lot more subtle, and I think a London audience will respond to that aesthetic.

Can you discuss the importance of space, lighting, freight, and location for your exhibitions?

I think all are really important, and there are some great spaces I would love to work with. The space in NYC was amazing because there were quite literally no constraints to any of these factors. Obviously shipping is a pain, but a reality that I suppose I have to consider… In reality though, it’s my job to make the paintings, and I let other people worry about logistics. One thing that many people find interesting is that I plan an exhibition around the gallery space. I go see the space, get a feel for it, and then think about the scale of the work and the number of pieces I want, and work to ‘fill in the blanks’.

The full show was a portfolio of 14 works. What timeline did you work with?

Is there ever enough time? I never count the time taken per work, but rather allot myself a specified amount of time for a particular body of work. I had initially given myself over 4 months for 9 or 10 paintings. I never do more than 12. I was approached by Kevin Arpino at Rootstein to do an additional show to outfit for their windows, the dates to correspond to my NYC show. So suddenly I had 5 more paintings to do in the same time-frame. I did my exhibition first, then the Rootstein works. I didn’t want overlap. To me, while related, they were two bodies of work. This was pretty crazy, but I always welcome a challenge. For London, I had 5 months, but I took a month ‘off-studio’. I tend to work well under pressure, though. But no…never enough time. I’ll rest when I’m old…right now, I feel like have work to do.

At another level, can you discuss your work with Rootstein, who’s philosophy is “constant innovation and boundless creativity” with an open canvas, – mannequin. What did this commission lead too?

Actually I was already working with the idea of sculptures falling apart…disjointed body parts, floating limbs, so making work for Rootstein couldn’t have fit better into how I was already painting. The resulting works were entirely my decision; I won’t work with any commission where they tell me what to do because that never works. I’m close friends with the CEO, Kevin Arpino, and he just said “I trust you”. And it worked. Kevin is incredibly inspiring and I learned a lot from him as well. He’s a true visionary and I think their philosophy is brilliant.

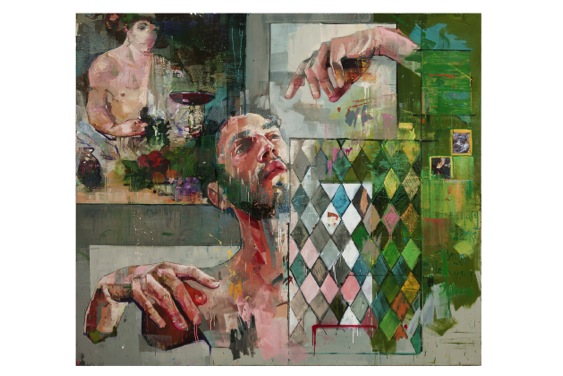

How often do you add work such as Caravaggio’s Bacchus to your canvases?

There are a lot of references lurking within my paintings. Some paintings have more obvious references, such as the painting of Bacchus in the background of Green Dionysus, or the reference to Botticelli in ‘1486’, but other paintings have sly nods: the presence of a contour line to reference Chavannes; another painting a response to “Whistler’s Mother”; another painting borrows from Doig; another from Gauguin. Sometimes it is just a subtle thing: a colour, the gesture of a hand, the composition, even the title, but I think as an artist I have a responsibility to the history that came before me, and an onus to be responsive to that. As a painter I don’t work in a vacuum, and I’m keen to draw attention to this, even if it is just knowledge for me to carry.

How do you find the sitters? Are many commissions?

I now avoid commissions like the plague. I don’t want to be told who or what to paint. It sounds awful but you can’t hire inspiration, no matter how much cash you throw at it. I’ve stopped taking commissioned work and I feel more honest as a result of it. I find my sitters anywhere, but typically I don’t like to know my sitter too well. I don’t like to think of them as portraits, and if they bring too much of ‘themselves’, I can’t use them the way I want to. I always say that ultimately what I do is very selfish, because I take what I want from my subjects, like conduits, to express something for me, and then I move along. It’s like a horrible mantra: love ‘em and leave ‘em.

Currently you are supporting Cancer Research in both Canada and the UK with your work on a T shirt. How did this happen? How can a reader purchase one?

I work with a lot of charities worldwide, and I believe in giving back. Artists can be so self-indulgent and solipsistic, they often fail to realize that there is a world with real issues beyond the confines of their studio walls.

I was contacted by Maison Twenty, who wanted to use my imagery for a t-shirt. Originally I was not keen on this idea until I asked them about if we could give all the proceeds to charity. I chose MacMillan in the UK and the Cancer Society in Canada and I’m splitting the proceeds to either. To purchase, you can go to Maison Twenty’s website.

Contact details.

www.andrewsalgado.com

www.facebook.com/andrew.salgado.artist

For sales inquiries: info@beerscontemporary.com

All other inquiries: amy@andrewsalgado.com

Andrew Salgado, London, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, August 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: