Aimee Lee Paper Artist - Cleveland, USA

Discuss the progress you have taken to get to paper making.

Music

Book art

Papermaking

It’s not inevitable that I became a papermaker, but it certainly suits my values and worldview. It also works with several constants in my life: a need to be alone to think, practice, sort things out; a joy found in using my hands to make anything and effect change; a reverence for the natural world; storytelling; and a desire to share with other people.

I always loved to write and make marks. I had excellent writing teachers, so I worked at that from a young age. But when I first played in a symphony orchestra, I felt deeply compelled by music. It took years to realize that being a concert violinist was not realistic, and I became an art major instead. I took an artists’ books class in my final semester at Oberlin College, and this opened a huge world to me where I could combine writing, image, narrative, and non-traditional media in one format. I spent the years before graduate school working in music and the arts and eventually found an interdisciplinary MFA program focused on book arts, which had a papermaking component. I had never considered papermaking or known a thing about it, but after my first semester in the paper studio, I was hooked.

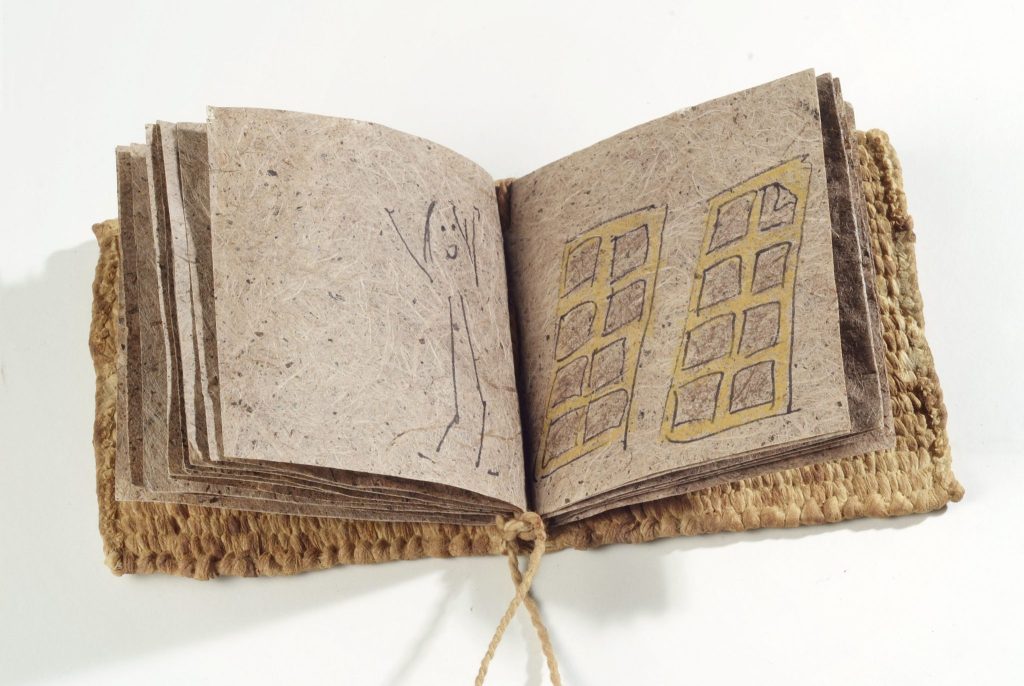

The Story of a Book, 2011, Pen and pencil comic on handmade slippery elm paper, slippery elm dyed hanji corded and woven, kon’nyaku covered covers. 3.25 x 3.25 x 0.5’’ closed

How influential was winning the Fulbright Award in your artistic career?

The Fulbright was a turning point for me and incredibly influential in focusing my artistic path. Not only did it establish institutional affirmation of my artwork and ideas, but it provided time and resources to pursue my heart’s desire. This is not a common gift, especially not for papermakers, so I took it with open arms and went as far as I could. Not only did I learn endangered techniques of Korean papermaking, but I learned related arts like weaving and fusing paper (jiseung and joomchi), natural dyes, and calligraphy. It was like an accelerated evolution of my media and techniques, speeding up a trajectory that I was on all along.

Explain papermaking in Korea and class – how this was to affect you and your own family?

Though hanji itself was prized throughout history, the people who made it often occupied the lowest classes of Korea’s hierarchical society (I’d venture to say that nearly every society in the world operates with class systems, so this is nothing out of the ordinary). It wasn’t an occupation to aspire to, nor one you’d wish upon your children. My family lived and operated in another class, educated in the country’s best schools and working in more privileged professions of medicine, business, and hard and social sciences. Thus, they did not immediately have the connections I needed to access papermakers. My goals may have seemed strange to my Korean relatives, but they never discouraged me from my research and did their best to help me—once I got the bug of hanji into their ears, they were more sensitive to seeing and hearing it everywhere they went and thinking of me. Eventually, a relative of an aunt led me to a hanji artist association, which is how I met my teacher. Most success stems from who you know.

I Still Remember Newark 2014, Beeswax on milkweed dogbane paper, Hark! Paper, wire 15.5 x 20’’

Expand on how you used different materials in your papermaking when you travel. The impact this has had on your work?

For many years I lived like a nomad, going from one residency to another in various states. Part of me loved this transience, yet it wore on the part of me that wanted to unpack my things more permanently and stay in one place. To ground myself in new environments, I would identify and harvest local plants to make paper, and used this paper for my artwork. The entire process helped me develop a different kind of relationship to place and made me grateful for the abundance yielded to me everywhere I travelled. I still root myself this way and continue to learn about ecology, conservation, and human resources as I meet generous and knowledgeable scientists who teach me about the plants all around us, from native to invasive. I went from using plants to save money to now using almost exclusively plant fibres that I harvest for more control over the final product and for the connections and meaning I find in the lengthy labour of it all. And I don’t have to be sparing, because there is enough local plant fibre to last me a lifetime.

You are passionate about craft forms prevailing over mass production, discuss your thoughts on this aspect?

Though mass production is here to stay, I think it is very important to recognize and support craft work around the world. Just as children today won’t ever know what they are missing when they don’t learn how to identify birds or plants (both from extinction and from a shift in education priorities), we will lose immense and valuable knowledge if we let human crafts practiced over centuries to be extinguished. I am a strong proponent of the deep and intrinsic value of making things with your hands and hand tools. There is an amazing exchange of information between the hand and the brain that enables both to evolve. Hand work also benefits the health of the entire human in ways that we are only beginning to appreciate.

Expand on your 3D work?

A lot of my 3D work comes in the form of woven paper objects, using the Korean craft of jiseung where strips of paper are twisted and plied into cords that are used to twine anything imaginable. Without a form or frame, a true jiseung master can alter the number of cords and control tension to shape pieces that served in the past as quivers, teapots, hats, chamber pots, furniture, shoes, and so much more. I look at historical models and the stories behind old pieces in certain collections, and then replicate them to my taste. I first try to mimic the original, and then experiment with changes in shape, colour, scale, and grouping. Each piece can stand on its own as an art object, but my connection to it is deeper even if it is unknown to the viewer.

For example, I have worked for the past year on a series of woven paper ducks. Most people visit the gallery and smile because they are a fun bunch of creatures. But their origin is the Korean wedding gift of paired (male and female), carved wooden ducks. These ducks are painted to mimic mandarin ducks, which mate for life and symbolize marital fidelity and fertility. I had seen an image of a wedding duck made of pasted paper, and later a picture of a woven paper duck. They struck me as ingenious takes on the usual wedding duck, and I wanted to teach myself to weave them. I’ve come a long way from the first attempt, and it required another visit to Korea for further study with my teacher, but I love all of them because each iteration taught me something new—not just technically, but about waterfowl gestures and personalities.

Paired Ducks, 2015, Corded and twined hanji, indigo and dahlia dye, Each 4.25’’ long.

Expand how Mina Takahashi’s quote, “Everything in the universe is contained in paper, earth, water and sky,” has helped you?

First, I want to attribute the quote’s background correctly. In the 2009 exhibition catalog for a Tokyo exhibit by the Friends of Dard Hunter (the show itself was “Paper – Future – Universe”), Mina Takahashi wrote an introductory essay called “It Contains the Universe,” which she closed this way:

Papermaking is a transformative medium. Paper begins as plant fiber, absorbs and reflects individual aesthetic impulses and human concerns, and pretty much accommodates anything from cardamom pods to war paraphernalia. In its very substance, paper embodies earth and sky and creative expression. In other words, paper contains everything.

The essayist wishes to thank Catherine Nash, one of the exhibition artists, for reminding her of the words of the Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, “As thin as this sheet of paper is, it contains everything in the universe in it.”

Thich Nhat Hanh’s “The Fullness of Emptiness” expands on the idea of how all aspects of the world exist in a single sheet of paper, though that is not the primary purpose of his essay. It reminds me of Dorothy Field’s excellent book, Paper and Threshold: The Paradox of Spiritual Connection in Asian Cultures (The Legacy Press, 2007). She notes,

We can think of craft as a metaphor for the creation of the world, a sacred event, no matter what story we tell to explain how it came about. The various crafts use the four elements, earth, air, fire, and water. Many creation stories from around the world draw on ancient craft technologies, which are attributed to the creator. To make paper, one starts with fiber from the earth, fire to purify the fiber, and water to suspend and work it so that the original fiber is refined and transformed. Still its essence remains, and it becomes more truly itself, a deepened and amplified self.

All of these insights remind me of my place in the grand cycle of papermaking, which keeps me grateful for the confluence of health, nature, discovery, and innovation that makes it possible for me to continue my work.

Lapse relapse, 2015, Ink and persimmon dye on kozo and hanji, thread, 8.5 x 13.75 x 1.5’’ closed, 8.5 x 26.25’’ open.

Can you explain the way Jang Ji Bang has influenced your own work?

Jang Ji Bang is my teacher’s paper mill where I trained in Korea. It gave me the foundation for all of my hanji making today. Obviously, the bulk of my technical expertise came from this experience, I was also cared for with daily and generosity by my teacher’s family and employees. Whether this affects my work, I don’t know, but it does affect how responsible I feel for sharing my hanji knowledge with the rest of the world.

Paper Dress 4, 2012, Hanji, milkweed paper. 33 x 22.3’’

Can you give us more information about the Morgan Conservatory and its importance to papermaking?

The Morgan is a very special, one-of-a-kind place where I have the great fortune of being artist-in-residence. It is a non-profit arts organization devoted to hand papermaking and book arts in Cleveland, Ohio, founded by Artistic Director Tom Balbo. He found a huge warehouse formerly used for machining auto parts, and transformed it with his own force of will, muscle, and volunteer support into a remarkable space that houses a papermaking studio, bindery, print shop, gallery, wood shop, store, office suite, and outdoor garden. We cultivate paper mulberry trees necessary for Asian papermaking (and harvest them every November, since they grow back each year), another plant to give us a viscous mucilage from its roots (also necessary for Asian papermaking), dye plants to colour our papers, and weeds like milkweed that do double duty as butterfly habitats and papermaking fiber.

The Morgan offers workshops throughout the summer, fall, and winter, hosting world-renowned teachers and artists. The gallery shows the range of possibilities inherent in papermaking, books, and printmaking. Our staff produces handmade paper for sale in our store and works on at least one major custom job each year. We also carry tools, books, decorated papers, posters, cards, origami paper, shirts, bags, and artists’ work on consignment. In 2010, I helped build their Anne F. Eiben Hanji Studio, which remains the only place in North America (and really, outside of Korea) where people can learn how to make paper from scratch in the Korean tradition.

In 2014, we launched our Eastern Paper Studio, which expanded the hanji facility to accommodate other Asian papermaking, such as Japanese, establishing the only public centre for this kind of learning. Artists can rent time through our open studio program in each of our studios. The Morgan has a busy schedule of outreach activities that include on- and off-site school activities from kindergarten through college and beyond, from serving people with disabilities to the Secret Tea Society. We have an internship program aimed mostly at college-aged students and an invaluable group of volunteers and members of all ages who help us year-round.

Essentially, the Morgan welcomes anyone who loves paper and books, and the people, equipment, and facilities necessary to support these arts.

Can you comment on strength and texture in your current work?

Strength is usually considered an inner attribute and texture an outer one, and people make lots of snap judgements about both based on first glance and long-standing assumptions. Other papermakers and I constantly prove the strength of paper in the way that we make, handle, and use it in our work, but most people still think of paper as weak and fragile. Paper made as long ago as 200 BCE still exists, and I could never make the kind of work I do without a very strong substrate. Anyone who has yanked one of my paper cords can attest to how tough they are; they rarely break as I pull on them with all the force of my hands.

One of the techniques I learned in Korea was joomchi, a method of crumpling and fusing sheets of paper together with no adhesive at all. It results in surface texture that can be incredibly fine or rough depending on the type of paper and intensity of handling. I have made garments out of paper, mostly for the wall (not meant to wear—but many artists make wearable garments out of paper), and love that I can create many different surfaces and textures from one kind of paper using one simple technique. Of course, this method was developed specifically for this kind of paper, which is why it suits hanji so beautifully.

Do you use dyes for colour or do you only use materials that have the colour you are wanting?

I do both. I use some favourite natural dyes (such as persimmon, dahlia, and indigo) on their own and in combination to provide what I need. I am also interested in surface finishes, and usually use methylcellulose, kon’nyaku, beeswax, rice paste, or my old standby of a final coat of persimmon juice to provide colour that seals my paper.

Marbled duck gourd, 2015, Corded and twined hanji, acrylic paint, 5.25 high x 4.5”

base diameter

You also teach papermaking. Can you expand on your classes?

When I began to teach in earnest, I focused almost exclusively on sharing my research on Korean paper arts. That was certainly important and informative to my students as well as to me, and I continue to teach at least one hanji-making course in the summer at the Morgan Conservatory. However, everything that got me to this place as an artist and teacher is also an important part of the story, and valuable to share, so I also incorporate textile and fiber techniques, natural dyes and finishes, book structures, and a bigger way of thinking about paper.

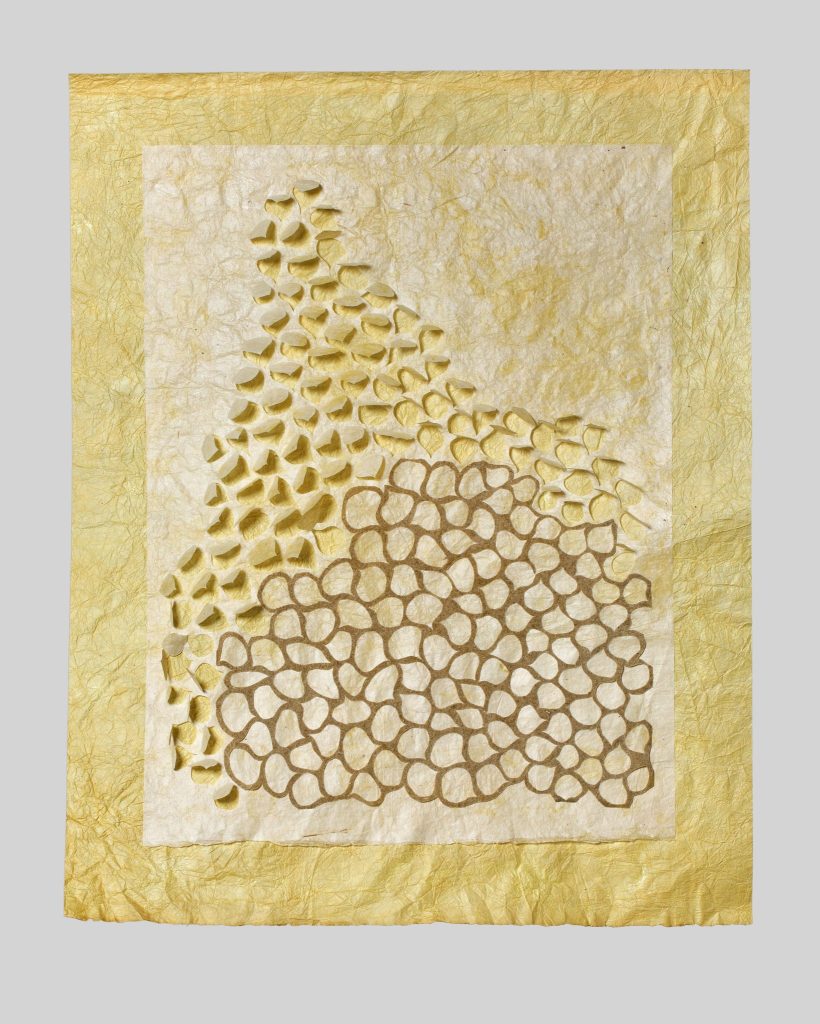

Vacancy study, 2014, Pomegranate dye and konjac on hanjai, hosta paper, 23.5 x 18.5”

My papermaking classes involve the processing steps before the actual sheet formation stage, so that students get a better understanding of the labour that goes into the process. I know that some students simply want to show up, pull sheets, and go home with nice paper, but it’s more important to me to zoom out and provide a larger context for the process—by zooming into each step. My hanji class may start with beating cooked fiber by hand and making thread and lace from bark, move into traditional sheet formation, and intersperse methods for using the paper, from making thread to books. Recently, I taught a milkweed papermaking class where I had harvested the plants, but I left it to my students to strip the base fiber from the stems and open the pods to separate the seeds from the silks. I cooked the fiber for them, but they had to rinse it and pick it to remove any remaining impurities, and then beat it by hand. I also ran some through a Hollander beater, and in the end they had at least six different types of paper from one plant—in just two days!

In July 2016, I will teach a 2-week course at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts based on the quote you asked me about before. Called “Paper Contains the Universe,” I describe it this way: “This workshop combines reflective time with intensive studio work as we create and transform paper in Eastern and Western styles with a variety of fibres, to understand how paper emerges from the earth and becomes anything we wish it to be. We begin with paper mulberry, processing virgin fiber into tissue thin sheets, move to ever versatile abaca, and use natural dyes and finishes. Then we explore the endless possibilities of paper as thread, yarn, rope, textile, book, and basket.” Like most of my papermaking classes, it is aimed at students who are unafraid of the labour, time, concentration, and cooperation required of craftspeople. If you are up to the task, I welcome you to join me!

Contact details.

Aimee Lee

Morgan Conservatory

1754 E 47th Street

Cleveland, OH 44103

USA

contact@aimeelee.net

Aimee Lee, Cleveland, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, January, 2016

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: