Jody Graham Painter / Drawer

How has your background influenced your art?

Everything about my life influences my art. I believe the marks that come out of me are a direct response to all I have lived, and they evolve as I do.

‘Polarized’ 2008 charcoal on paper 76cm x 56cm

‘Polarized’ 2008 charcoal on paper 76cm x 56cm

If I were to answer this question through a few key memories that I believe shaped my development, these come to mind:

When I was young, before starting school or around that time, I used to help my dad colour in his drafts plans for machines he was designing. I remember how excited I was to be on the floor, colouring in the parts I was allowed to. Looking back now, I found more joy in that than in many other childhood games. I was a daddy’s girl, and it felt meaningful to be allowed to help with his work.

Bowerbird collecting and organising my stash Photo credit James Blackwell

Bowerbird collecting and organising my stash Photo credit James Blackwell

My dad was always drawing, not to create pictures, but to work through ideas for the machines he was building. My mum, too, had an interest in art. At an early age, I found her old school books with ink and pencil drawings in them. I loved looking at those drawings.

Another strong memory from my childhood is the Picasso print that hung in my bedroom. (Picasso ‘A Mother and Child and Four Studies of Her Right Hand’ 1904). I looked at it constantly as a child. I still have that print now, and I often wonder how much its imagery has shaped me. I have drawn since I was a child. Everything I encounter influences my drawing, especially my emotional states. Whether I am happy, sad, angry, or quiet, I draw in all these moods. Over time, I have come to understand just how valuable difficult feelings can be when making art. I draw my feelings out rather than bottling them up.

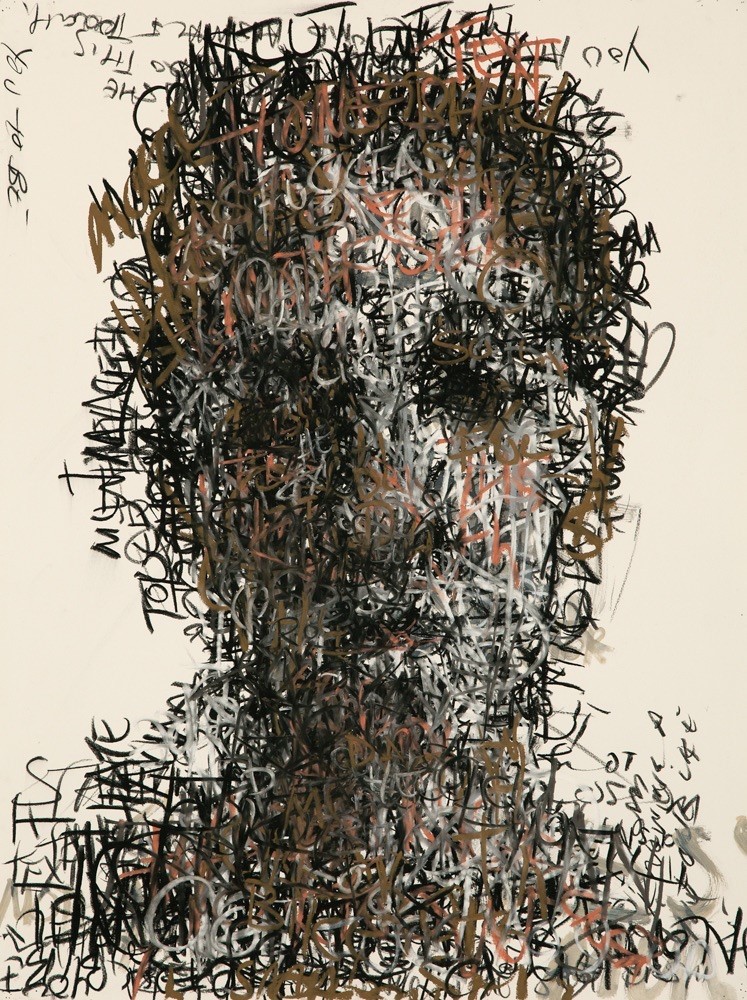

Borderline’ 2015 charcoal and pastel on paper 76cm x 56cm

Borderline’ 2015 charcoal and pastel on paper 76cm x 56cm

Birds

Expand on …

Their eyes

Movement

Addition of the use of one colour

‘Freedom’ 2023, 140cm x 114cm , charcoal from Black Summer bushfires, ink, pastel on paper

I do not just look, I really look. I absorb the world around me like a visual detective!

I have read that they, That is why, when I catch a bird watching me, I stop. I let them look. I give them the chance to decide what kind of person I am. That moment of eye contact becomes our unspoken greeting, a visual handshake, if you like.

Jody Graham drawing a magpie in flight with charcoal sticks from Black Summer Bushfires.

Jody Graham drawing a magpie in flight with charcoal sticks from Black Summer Bushfires.

I take the time to engage; and I am often rewarded. Birds come close. I get to see the shimmer in their feathers, the glint in their eyes. These fleeting, intimate moments stay with me, and they inevitably find their way into my artwork. Eye contact has become a recurring theme, not just for what it says about the birds, but for what it reveals about us.

‘Yellow-tail Dance’ 2025, 98cm x 150cm , charcoal, ink, acrylic, pastel on paper, Image Jody Graham

‘Yellow-tail Dance’ 2025, 98cm x 150cm , charcoal, ink, acrylic, pastel on paper, Image Jody Graham

Movement is just as vital to my process. I do not sit still when I draw. I move with the energy of the bird, especially when they are in flight. The gestures, their shifts in direction and balance, guide my hand and arm as I draw. Gestures, their shifts in direction and balance, guide my hand and arm as I draw.

‘Somewhere to Land’ 2020, 29cm x 42cm, charcoal from Black Summer Bushfires.

I choose to work with a reduced palette, intentionally. I do not want to draw or paint with lots of colour. I prefer exploring all the marks I can achieve through charcoal drawing. Occasionally, I add just one or two colours, like the flash of red or yellow on a black cockatoo. I do this to mimic that burst of brightness you catch when you see a bird in the wild.

The sight of a bird, their sound, their inquisitiveness, and their freedom, inspires me!

Tell us how you have expanded beyond known art materials to,

Burnt sticks.

Your invention of gloves

I think the urge to make my own materials has always been with me, even before I understood what it was. As a kid, my family travelled constantly for my dad’s car racing. We were in and out of motels across the country, living out of bags, always moving. Somewhere along the way, I started collecting things, tiny motel soaps, sugar packets, sauces, salt and pepper sachets, jams. I kept them tucked away in a private stash.

Collecting after the Black Summer Bushfires

Collecting after the Black Summer Bushfires

At the time, I did not really question it. But looking back, I can see it was about comfort. In a world that shifted constantly, those small, ordinary objects gave me a strange sense of control. I told myself, if we did not make it home, I would still be okay, I had my soaps and jams. That survivalist mindset has stayed with me, and it runs underneath much of what I do today. My practice has always involved collecting, salvaging, and transforming what others throw away.

Discarded things, what some might call junk, have always caught my attention. Junk feels alive with potential to me. I sometimes say I am a thwarted sculptor, because even though I mostly work two-dimensionally, deep down I wonder if sculpture was my true calling. Making my own tools from discarded things I find, satisfies a certain sculptural itch. I like hanging my handmade implements from hooks in my studio, having them surround me and reaching for them while I draw and paint.

This instinct becomes even more important during residencies, when I do not have access to my full studio. I become highly resourceful, using whatever I can find. It forces me to invent and adapt.

One of the most profound examples of this happened in the aftermath of the Black Summer bushfires. I was working on an artist residency at BigCi – Bilpin, NSW that is in an area where charred trees and branches were everywhere, haunting reminders of what had been lost.

I began using these burned fragments to draw with, knowing that many of them had once provided shelter and perches for native wildlife. To use a branch that may have once held a Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo felt deeply symbolic. It was a way of drawing not just with the landscape, but with its memory, calling attention to the fragility of these ecosystems and the urgent need to protect them.

Charcoal drawing stick made from discarded material from Black Summer Bushfires

Charcoal drawing stick made from discarded material from Black Summer Bushfires

The tools I make are unpredictable, and that is what I love most about them. They leave marks I could never plan, spasmodic, awkward, often beautiful. And in using them, I consume less, recycle more, and do my bit to clean up discarded rubbish.

Jody Graham – Using later version of gloves – painting gloves, photo credit Richard Nolan-Neylan

Jody Graham – Using later version of gloves – painting gloves, photo credit Richard Nolan-Neylan

One of my favourite examples of this process is how I started making my drawing gloves. This also began at BigCi in Bilpin. Each day I walked long distances, often up and down the Bells Line of Road – looking for coffee but really scavenging for materials. As much as I appreciate nature, it is the discarded, human-made stuff that grabs my attention. I am fascinated by the ghost of an object’s past life, who used it, how it ended up abandoned.

One day, I found an old workman’s glove by the roadside. It was worn, dirty, and completely beautiful to me. Back in the studio, I stuffed it with rags, mounted it on a stick, and started using it like a brush. It was strange and wonderful. But since I was mostly drawing at the time, I needed a version that could work with charcoal instead of paint. It took months of tinkering, but eventually I figured out how to attach charcoal to each finger and thumb.

First set of Drawing Gloves photo credit Richard Nolan-Neylan

First set of Drawing Gloves photo credit Richard Nolan-Neylan

I will never forget the day I got both gloves on and started using them for the first time. I was grinning, completely thrilled with myself, when a friend suddenly walked into the studio. He froze, took in the scene, and burst out laughing. We both did. It was one of those perfectly absurd, joyful moments in the studio—when creation feels so strange it becomes magic. I will never forget the look on his face.

Jody Graham – Using later version of gloves – painting gloves, photo credit Richard Nolan-Neylan

Jody Graham – Using later version of gloves – painting gloves, photo credit Richard Nolan-Neylan

You are so open and frank, discuss.

‘I like leaving evidence of mistakes in my drawings because I think there is integrity in the struggle to get it right.’

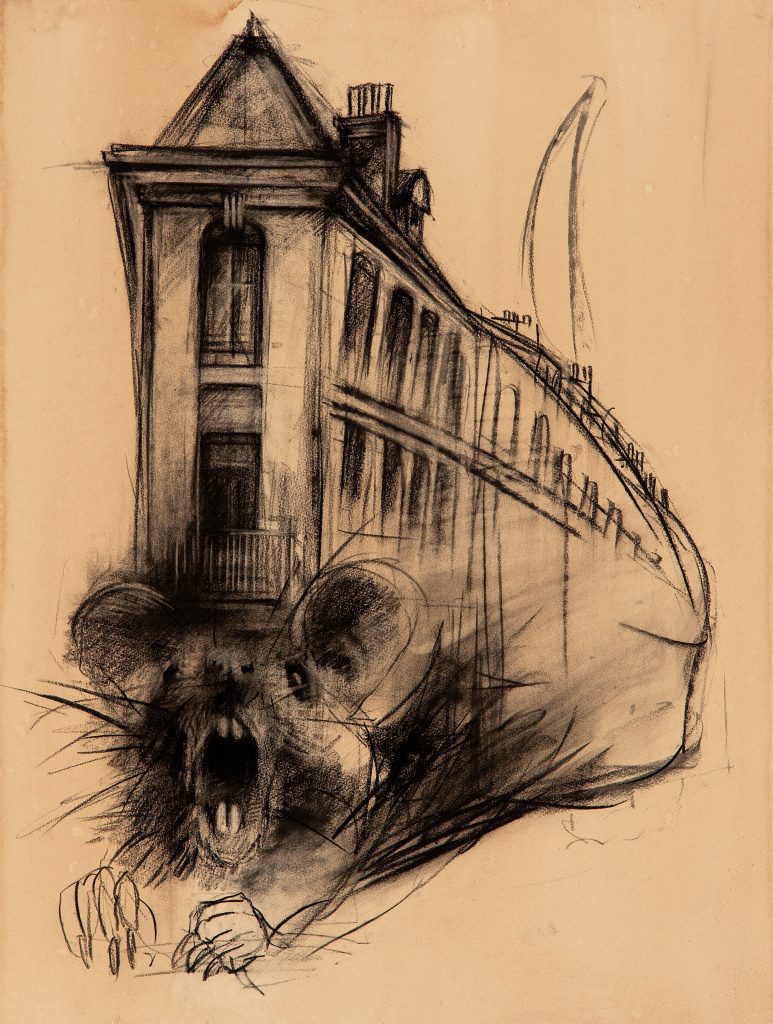

‘Rat-house’ 2022 charcoal and coffee on paper 76cm x 56cm

Can you expand on this through one piece.

I like to leave evidence of mistakes in my drawings because they reflect who I am. I am human, flawed, evolving and I want my work to carry that same honesty. A smudge or a misplaced line is not a failure; it is part of the process; a visible trace of the effort it takes to get things right.

I draw by eye, levelling and measuring by sight, no projectors, no shortcuts, because I value the challenge. The back-and-forth of adjusting and reworking: that is where the real satisfaction lies. It is a human process, full of imperfections, and that is exactly what I want to preserve in the final piece.

‘Little Queen’ 2016 charcoal on paper 120cm x 114cm , Image Jody Graham

‘Little Queen’ 2016 charcoal on paper 120cm x 114cm , Image Jody Graham

You can see this in Little Queen, a drawing of a corner building I pass often in Newtown, where I live. I am drawn to older architecture, especially corner buildings that quietly watch over the streets. Capturing the old telegraph pole was important too; they are disappearing, and I want to hold onto these details before they vanish.

In Little Queen you will notice faint construction lines and an earlier position for the pole and streetlights. I left them there intentionally. They are not mistakes anymore; they are evidence of thought, revision, and the human touch that defines my work.

Contact:

Jody Graham

Deborah Blakeley, Melbourne, Australia

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, September 2025

Images on these pages have all rights reserved by Jody Graham

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: