Tracy Krumm Crochet Artist - St. Paul, Minnesota, USA

Childhood experiences passed on by Grandmothers have influenced the direction of your artwork, please comment?

By teaching me to crochet, tat, embroider and sew, my grandmothers introduced me to the legacy of women’s work. These activities bonded us across the generation gap and introduced me to a world of creative practices that embraced beauty, labour and connections between cultures–and women–all over the world.

You have a definite connection between combining math and the natural sciences. Can you discuss this?

My interest in ecology and environmental studies has always been a huge influence on my artistic practice. My love of math and other linear and non-linear systems gave me an immediate connection to textile-specific practices. The fact that the very nature of textile structures and surface design are rooted in pattern and sequence made textile studies a viable approach to making art when I first began to be interested in the idea of being an artist as a profession as opposed to just a pastime. The natural sciences and my particular love of botany provided me with a background to understand the essential nature of the materials I was attracted to. Being able to analyse things from an academic standpoint, both scientifically and culturally, has influenced my art making practice far more than the history of art or the work of other artists.

‘Squared 9 Patched’

A combination of need and serendipity happened simultaneously during graduate school. I found a spool of wire in a free box in front of a science lab. It immediately solved a problem of how to unite the found materials I was working in a way that felt more physically substantial than using a fibre-based material. After experimenting further, I realized metal–soft, annealed metals of all types–could be used to construct textiles with qualities and characteristics similar to fibre-based textiles. But they had this edge, this potential, to do something different in terms of structure and texture and colour. My excitement in discovering this love for metal is still with me–that’s why I continue to use it.

‘Squared 9 Patched Detail’

Your first exhibition was in 1988 at the “Young Americans”. Since then you have been involved in over 150 exhibitions; can you discuss 2 or 3 highlights and how they influenced your work?

“Young Americans” at the (former) American Craft Museum was a huge show for me because of the tremendous exposure. It really allowed me to start my career as a studio artist. My work has changed significantly from that period–it was 2-dimensional mixed media based in weaving and papermaking at that point. The next big “aha” moment that set me on the trajectory leading me to where I am now was a show at “Plan B”, a hipster renegade art space in Santa Fe. There were several teams of local artists invited to do installations for a show called “Airships and Submersibles” and this exposure evolved into a long relationship with Linda Durham Contemporary Art in Santa Fe. Around the same time, I was selected to participate in the Betonac Prize, which opened in Belgium and toured Europe, so that got me over to Europe for the first time to scope out the contemporary art scene. Lately, it has been a move back to Minnesota after teaching college for 10 years–where winters are snowy and cold and where I now control my days instead of students and administrators– and recent travel to Peru and Hawaii that have provided the physical, spiritual and cultural extremes that seem to fuel my work. Combining this with the fact that I have been lucky to have continued commercial success keeps me productive in the studio.

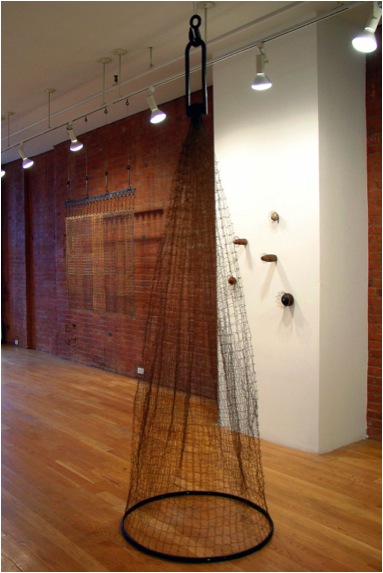

Installation

Installation

How difficult has it been to have your work accepted in mainstream galleries?

I mentioned my relationship with Linda Durham in Santa Fe. She was a huge supporter of my work and for over a decade, her gallery was pivotal in placing my work in a contemporary fine art context. I was lucky to have her and a number of other excellent contemporary art dealers take my work to significant art fairs in the US and Europe. My current gallery relationship with Andrea Schwartz in San Francisco has been essential in keeping my work where it needs to be. I have put enormous trust and faith in my dealers and then stepped back and let them work their magic. Having the right dealer at the right time is super crucial–and does not always happen.

‘Draped (Screwed)’

You have received two grants from the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe. Can you discuss your thoughts on current Folk Art?

What constitutes folk art could be up for debate; to me it has always meant simply work made folks engaged in cultural production. We can discuss intention, training and utilitarianism as factors; it is generally work that is driven by the human hand, channelling creative energy. This means everyone can be a participant. My projects at the museum in Santa Fe allowed anyone who wanted to contribute to a several installations that could not have been realized by me alone.

The sheer amount of work meant many participants were needed and the processes used had to be simple to ensure participation by everyone, no matter their abilities. This act of making as a community tied us to cultures all over the world that rely on shared values and community engagement to get work done. Creativity is a powerful force because it lives in everyone.

How important is it that the craft of crochet lives on?

Like so many other important craft processes, the language of crochet has connected so many generations of people and so many different cultures for the past 150 years or more that I can’t imagine it will ever disappear. Cultures all over the world engage with it as a practice for making objects of both utility and beauty, and artists around the world choose it for its ability to create structure in a certain way and for its ability signify particular conceptual content. I cannot imagine a world where there is not a discussion about the both the hand and technology and where these two things meet and don’t meet. Crochet and other hand constructed textile practices will always be part of this conversation.

‘Strapped (funnel)’

Can you discuss how crafts are defined by the generation that produces them?

Every generation has to define things in terms of itself or it won’t be understood if it isn’t in the right context. This is what keeps things fresh and alive. We are not always seeing things take on a radical physical transformation, as all craft processes seem to have some defining essences that resonate around the world and withstand the tests of time. As someone who has been involved in discussions about craft for over 30 years as student, teacher, production weaver and professional artist, I have seen the reinvention of the wheel over and over. Folks are still crocheting, forging and stitching “just like in the olden days” but every generation has new reasons for doing it. The crafts could be seen as benchmarks that are constantly being related to current social conditions and the relationship of every generation to what craft is becomes part of its history. It is a constant learning process for all of us involved and the field gets broader every day. You really can pick where you want to be in the discussion, whenever and wherever–there is no right or wrong place to be.

‘Steel Chains(Carrick)’

Your work is all about connection. Can you discuss this relationship in your work to 1 or 2 particular pieces?

Ideas about connection are both physical and conceptual parts of my work.

‘Tapper (Anchor)’ Detail

The joining of materials is often the visual focal point of a work.

This crossing or momentary joining of some sort of duality exists in everything I do. It is the point of intersection and accommodation that I love to play with, where strength and weakness come together and you don’t know which is which.

In “Taper (Anchor)”, the metal armature is encased in the crochet. The connection of the materials has an interplay that is totally significant to the structural integrity of the sculpture. It’s not just decorative, it’s essential and it’s highly calculated.

‘Tapper’’

Discuss how you use shadows in your work?

Shadows give the work an extra dimension that can either attract or distract. I try to keep the shadows to a minimum in my individual portfolio photographs. But in an exhibition, shadows can add an extra layer of depth and intrigue to the work. They can be used as a non-permanent drawing, record or impression of the work and can expand the boundaries and complexity of the work. Of course, if that is not part of my intention in an installation, then they are just a nuisance. It all depends.

Discuss the importance of hanging space for your work?

My work has an aspect of flexibility built into it. Every piece becomes a part of something greater that comes together to activate space in a certain way. Each space dictates the nature of how a group of work can come together to be displayed. The pieces have to play off each other in a way that makes them all worthy of being there. I often fabricate multiple armatures or hanging devices to accommodate whether a piece needs to be on the wall, hanging in space or freestanding. Many pieces can be shortened or lengthened to some extent without losing integrity. I get to make this call each time I do an installation and it helps keep the work fresh for me.

‘Strip (wrapped)’

Take both a 2D and 3D piece that you have enjoyed working on and discuss?

I think the pieces that have an unexpected resolution are always the most satisfying to work on. The 3D piece “Lure (Pouch)” came from taking two other unsuccessful pieces apart and working off them to create a new, hybrid form that was much more dynamic.

‘Lure (Pouch)’

The same thing happened with the 2D piece, “Plaited”. It came together as I took apart a larger net from an older curtain-type piece, crocheted it back together and then started to crochet a series of strips to weave through it. The hand labour involved makes me not want to waste any of the material so I recycle my own work. I also love combining process, like plaiting and weaving, into my work. And I love to work using multiple elements, since I can finish several of these every day, which is gratifying. Then when I have a pile of them, they can come together to make something bigger and better–something I might not have been able to conceive without the parts to the whole in front of me.

‘Plaited’’

Often crochet conjures up small pieces made by Grannies, whereas your work is large and sculptural. Can you expand on this?

Personally, I love the image of the small pieces made by grannies. It is so nostalgic these days. Who makes a doily anymore when you can buy one at either the discount or the antique store for $2? Now there’s a cultural contrast! I think it is partly this desire to seek out compelling contrasts that led me to make work on a large scale and partly, it takes me a long time to figure out what I am doing so I have to embrace this thinking-through-making sensibility. I am labouring away, making material, not always knowing what it is going to be until the pile is quite large and then the reality of what it needs to be comes together.

Can you explain your involvement with the Cultural Exchange through Visual arts and the US Department of State?

The US State Department’s Art in Embassies maintains an on-line artist registry, where over a decade ago I submitted images for consideration. My first contact with them was back in the 1990’s when we were still sending out slides and my work was still two-dimensional. They have excellent curators who are constantly looking for new work for loan to their embassy exhibitions. I was fortunate enough to have work selected for the new American embassy in Djibouti and to have the work purchased permanently for the collection.

‘Table (Husks)’ Detail: The US State Department’s Art in Embassies

You work in your studio full time now. Can you explain how being able to give your time fully to your art has given growth to your work, inspirationally and in new directions?

There has been a lot more time to think, to fret and to sift out bad ideas. I do not have to approach my work with the desperation of time constraints. You make decisions very differently when you have more time. I don’t know if this is good or bad, it just is and takes some getting used to. I spend more time thinking about whether or not the work I am doing is worthwhile and if it is true to my nature. I have dabbled in a lot of other materials and processes in the recent past, but none of them has suited me yet. Maybe as my lifestyle continues to change, something that appears to be a more radical shift will click. For now, I am trying to take more time appreciating my surroundings to soak in new inspiration and to establish some meaningful relationships with my new community in the Twin Cities. It doesn’t get any easier as you get older. There is a lot more weight and effort involved in everything I do right now.

Tracy Krumm, Blacksmithing

Everyone loves to see inside an artist studio. Can you show yours and explain how you have had to adapt things for storage and your specialist needs?

My studio has always been pretty spartan and I am not a huge stockpiler, as I have moved so many times in my life. I have always been extremely organized, as my studio usually doubles as some other type of living space. Everything has its place and gets packed away in a plastic tub when it is not being used. I tend to have several piles on my worktable at a time, as I usually work on several pieces at once. And fabrication equipment always lives in the garage. I try to keep it simple. Think “pile of wire and crochet hook in a tote bag” and I am good to go!

Tracy Krumm, in the studio

Contact details.

Website:www.tracykrumm.com

Email:tracykrumm@gmail.com

Tracy Krumm, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, April, 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: