Tessa Bunney Photographer - North Yorkshire, UK.

Can you expand on FarmerFlorist Exhibition?

How did you become involved?

I have been working on FarmerFlorist for just over 2 years – prior to that I had been living in Laos for four years enjoying travelling and photographing both for various clients and my own projects all over southeast Asia. Although I wasn’t really looking for a new long, term project I happened to notice a nearby farmer’s market in Hovingham, a small village nearby my home in Yorkshire, UK. There was a list of stallholders one of them being Ducks and Daffodils, an artisan flower grower and florist who was based nearby. I noticed that they are a member of Flowers from the Farm, so I got in touch with Gill Hodgson who set the up the not-for-profit network in in 2011 and the project developed from there.

From the series Farmer Florist

The importance of British Flower Week?

British Flowers Week is the annual celebration of British flowers and the UK cut flower industry. It is the initiative of New Covent Garden Market, London’s original fruit, veg and flower wholesale market and has been running for six years with the aim to promote British flowers, their growers and the independent florists working with them. It provides a focus for celebrations and events of course British flowers are available all year round. It seemed like an appropriate time to launch my project.

The importance of making people aware of British grown

We are a nation of farmers, of gardeners, of flower lovers and our cut flower industry is worth 2.2 billion pounds a year. Flower farms were once a familiar feature of the British countryside and market gardeners grew flowers among their vegetables. In the 1800s, larger farms sprang up as transport links improved and daily trains carried violets from Dawlish, snowdrops from Lincolnshire and narcissi from Cornwall. Flower productions has always necessarily been linked to transport, and with planes came distance. Now we can have any flower at any time of year, flown in from the equator, or hothouse in vast Dutch greenhouses.

From the series Farmer Florist

Recently several smaller British flower farms have sprung up, fuelled in part by the wider, resurgent interest in locally produced, seasonal, sustainably grown produce.

“Nothing is exotic, they are all flowers that have been grown here for centuries. The issue is that people have got so used to a diet of chrysanthemums, carnations, roses, lilies and gerberas that there is a whole generation that don’t recognise anything else”. Gill Hodgson, Fieldhouse Flowers.

How did you choose the growers?

To start with I used the Flowers from the Farm website to discover flower farmers both in my area and further afield. They are quite social media savvy and many of them have wonderful Instagram accounts, so I found others through that. I asked for recommendations from other growers. There are so many to choose from (over 500 members) it has been very difficult aside from my local growers whom I visit regularly I am looking for a wide geographical spread. Recently I have expanded the project to include larger scale commercial growers in Lincolnshire who operate a different model of flower growing, but equally as fascinating.

SE Warner + Son, Spalding, Lincolnshire

Can you comment on your role as a photographic – Artist.

I hope that my role is a collaborative one where the communities or individuals I work with share their stories with me and I use my photo skills to interpret them.

I employ a long-term art-based practice to address some of the wider issues of landscape. This offers an alternative approach to conventional news journalism with its tendency to ‘parachute in’ on issues for a fast story. Instead, I adopt the growing practice of slow journalism, which advocates sustained relationships between photographer and subject, working closely with local people to enable more meaningful and complex stories about landscape and development to emerge.

Even with difficult subject matter for example photographing people doing something I might not be totally comfortable with, then I try to present the issue in a respectful way and allow the audience to make up their own mind.

For whatever reason, people generally find it easy to open up to me – as an outsider, a photographer, it’s quite remarkable what people will tell you and then I have to decide about what I should share further.

Your images are also works in sociology, discuss this aspect of your work.

Unlike other photographers I am not a sociologist by training or in fact in any other subject other than photography, so any sociological aspect is literally achieved by spending a long time talking to people and working in the field and allowing the story or issue to emerge in time. I often work within countries or with issues I originally knew nothing about. I prefer to start the work and allow the issues to surface and then follow up with academic research to validate my own findings. My projects very rarely start with that kind of research, my ideas are more likely to come from a radio feature (Hand to Mouth), a map (Home Work), a commission (Moor and Dale) or inspired by someone I meet or exploring a landscape.

You travel to remote places, for example Romania’s Carpathian Mountains discuss how you prepare for a trip like this.

For my project in the Carpathian Mountains – I travelled firstly on a brief research trip, so I had no set ideas about what exactly the project should be at that point or what was possible. However, I was particularly interested in shepherding and during the research trip I tried to discover exactly when activities such as the Measurement of the Milk Festival would take place, so I could plan to be there at times. I returned 8 times in total, each time I went back to the Maramures region and then to somewhere else in the mountain range so that I had the mix of getting to know several villages and people within the villages well as well as the excitement of exploring new areas. I went at different times of year and responded to the yearly cycle of the seasons. There was very little formal planning other than transportation, booking a translator etc.

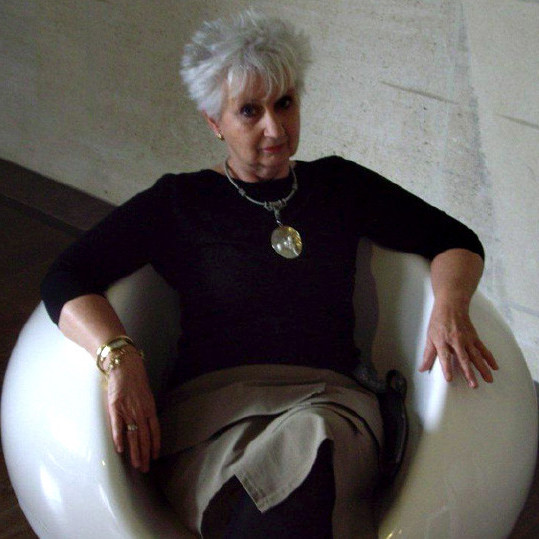

Tessa Bunney

Other countries I have worked in especially Communist countries such as China, it has usually been necessary to prepare a detailed itinerary in advance in case of being stopped at army/police check points. Although not usually too rigid, this is difficult with the way I work as it doesn’t allow for the random exploration which I enjoyed in Romania and other European countries.

Expand on how you build up a relationship that allows you to take portraits especially in remote places.

This might differ country to country or how much time I or they have. For my own projects, in general I try to spend as much time as possible chatting to people or photographing them working – and then make a portrait at the end of the day or some other appropriate time during their activities. Sometimes I might meet people briefly whilst wandering landscapes and villages, make their portrait and then go. At times if I am travelling remotely especially on foot, the only way to have time with people then I need to stay with them as a guest in their homes. When I am working on personal projects, I’ve found, as many other photographers have, that the more remote you go, the harder the journey, the more authentic or unique the experience will be. There are many ethnic minority villages in Laos and elsewhere along roads where tourists stop often and then the experience is different. However, it can be more challenging if you meet someone who has never seen a camera before or has a set idea of what a photo should be normally because their only experience is in a formal portrait studio. Overseas, I always use a translator so that they can explain who I am and what I am doing.

Generally, though if I have to work in a rush or I feel the person is uncomfortable then the photo won’t be any good anyway, so I will leave it.

This image of an Akha women spinning cotton as she returns from the field is one of my favourites from my time in Laos – we (me and a local guide/translator) had just arrived at the edge of her village after a boat trip and an exhausting six-hour hike uphill, we turned the corner and she was there, my heart skipped a beat. We stopped to chat to her briefly, Sivongxay asked her if it was OK to take a photo, I took a few versions taking no longer than a few minutes and off we all went on our separate ways.

This portrait of puffin hunter Jakob Erlingsson was taken in Iceland.

I had heard about puffin hunting and got in touch with the tourist information office in Vestmannaeyjar to see if they could put me in touch with someone which luckily, they were able to. I spent a few days photographing Jakob at work, at first the weather was terrible and then eventually some days later it cleared up and I asked him to pose for the portrait after a mornings hunting. Taken in 2001 this image already has value as a historical document as by 2011 and 2012, breeding failures had taken such a toll that puffin hunting was banned in Vestmannaeyjar. In 2013 a five-day puffin-hunting season was allowed at the end of July. Now I believe there is now another complete ban

This is a portrait of a member of Old Glory Molly – Molly dancing is a form of English Morris dance and is one of the traditional dances from the fens of East Anglia. It traditionally only appeared during the depths of winter as a means of earning some money when the land was frozen or waterlogged and could not be worked. The original “ploughboys” blackened their faces as a disguise to escape recognition and the consequences of their mischievous actions.

Here I set up a portable studio at ‘A Day of Dance’, the largest annual gathering of Molly dancers in the UK – I watched and photographed them dance and then asked them if they would pose for me one by one in front of my backdrop.

Discuss your landscape work using ‘Tidal Pools’ as your reference.

Although my work is about landscape, I don’t really consider myself a landscape photographer, I’m not interested in photographing wilderness or ‘peopleless’ places when I look at a view, I want to know who lives there and how it operates.

I’m very interested in land issues and how we use it. I’ve also got little patience for waiting for the ‘perfect’ landscape shot in terms of light, if I am somewhere then I will take the photograph if the conditions are ‘right’ for the purpose.

This image of Mousehole tidal pool was the first image I made in this series – taken whilst on a family holiday in Cornwall. I just happened to be there by chance, the light, the tide and the activity was just perfect and luckily, I had a camera with me. The incongruous nature of the concrete within the natural landscape fascinated me and when I got home I did further research and realised there were a number around the coast of the UK. I then pitched the idea to the Financial Times magazine and they commissioned me to work in southwest England for a week to photograph more tidal pools – quite a bit of research was involved to make sure I arrived at low tide otherwise the pool would not be visible! People and activities were of course the crucial element which depended on luck and waiting around.

So many of your projects are whole stories in themselves. Can you expand on both the photographs and the story behind your Oxfam Portraits for The Telegraph?

This was a very short story (for me) which was taken whilst on an assignment for Oxfam – shot in only a few hours but I guess the idea was germinating during the week I was working with them on Bantayan Island in The Philippines. On an early morning walk I bumped into the woman carrying a bowl of fish on her head and then devised a project around her activity which commented on the fishing industry in Pooc village post Typhoon Haiyan.

You have four books. They are all in editions of 1000 discuss both the books and the decision to limit the edition.

1000 copies seem to be the standard edition for photo books in the UK unless it is a very populist or commercial subject matter.

My four books have been produced to accompany exhibitions and as standalone publications of bodies of work. Much of my work, especially personal projects are supported and funded by a combination of a gallery, Arts Council England and self-funded and often a combination of all three. Some series are also part funded by editorial commissions. I love working editorially but discovered early on in my career that as I liked to work slowly and spend time with communities arts funding enabled me to do this more successfully.

Moor and Dale and Hand to Mouth were produced to accompany exhibitions and were funded by the galleries.

The bird man holding a brace of pheasants on a shoot at Swinton Estate, Nidderdale, North Yorkshire, UK

Home Work was published by Dewi Lewis with funding from Arts Council England, this was the first book where I chose the designer and had full decision-making control over how the book should look, what should be included and worked closely with the designer, James Corazzo, on the edit etc.

Järvenjää/Lakeice was self-funded and was more of an artist’s book with an edition of 250 produced as a lasting legacy of a residency in Finland.

In all these publications, use of text in different ways to accompany the images was a much discussed and considered element of them. I love maps and information but in each book these elements were handled differently depending on how much it was though that the images should speak for themselves (as in Hand to Mouth with extra info at the back of the book)

Contact details:

Tessa Bunney

www.tessabunney.co.uk

Tessa Bunney, North Yorkshire, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, July 2018

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: