Lan-Chiann Wu Contemporary Ink Painter - California, USA

Can you discuss your East and West arts education and the fusion of both in relations to your BFA with highest honours from Taiwan and your MA from New York University?

Throughout my study in the fine arts, I have worked with different paint media, such as watercolour, oil and acrylic paints both in Taiwan and in New York. However, I discovered that I have strong connection with ink painting. Ink painting allows me to express a deeper meaning that goes beyond the image you see. This is the same way with poetry, which has deeper meaning beyond the rhythm and beauty of the words. Ever since I was very young, I have been attracted to western painting, especially with regard to the use of perspective, light, and representation of volume.

At the Chinese Culture University, I was trained in the ancient tradition of ink painting. It is very typical in this field that artists first learn from studying and copying old masterpieces. The traditional way of learning Chinese ink painting encouraged artists to use their own wisdom to understand the spirit of the masters and then, over the years, use that knowledge to become independent, so that the artist eventually would make his/her own creative work.

Studying art in New York City rounded my artistic formation and gave me the opportunity to further explore blending Chinese ink painting with Western modes of representation. Both Western art and Chinese art have unique qualities, which I equally value and embrace.

To me, art is a universal language. Art is often an unspoken language, which can be understood intuitionally by people across time, space and culture. Making painting is a calling to me, and creating work that focuses on the significance of universal humanistic values is my mission. I hope my work provides people with a moment of contemplation on the beautiful and meaningful moments of life.

Discuss how your earlier training as an assistant under Au Ho-nien influenced your training?

One of my high school teachers suggested that I seek out the Chinese Culture University in Taiwan, which at that time, had one of the best painters in the country, and I chose to learn from him. His name is Au Ho-Nien, and is one of the greatest living masters of the Lingnan School of painting. I studied four years with him. He is a great master, who is still very active in the field today. I was very fortunate to have been his student. I also had the opportunity to study with other masters at the Chinese Culture University in Taipei, who taught me several different styles of ink painting that included very fine, detailed brushwork.

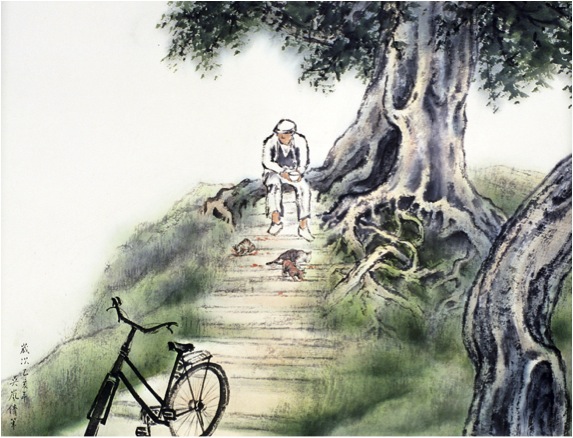

I have had several excellent teachers who helped me advance my painting skills and understanding of life. In particular, my mentor, Au Ho-Nien, has been extremely generous in this regard. In my earlier work, Solitude (1994), you can see the influence of his Lingnan style artwork in mine.

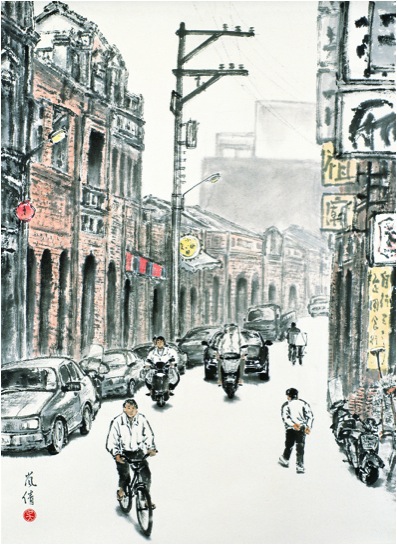

As I mentioned before, I have always been attracted to the use of perspective and light, more commonly found in Western painting. Therefore, in some of my earlier work, you can see a mixture of Lingnan and Western schools as, for example, in my work Old Street in Sanxia, which I created while I lived in Taiwan in 1993. Today, I have moved on from Lingnan, not because I reject it (in fact I think it is incredibly beautiful and expressive), but because I wanted to find my own direction.

‘Old Street in Sanxia’

One of your older paintings ‘Old Street in Sanxia’ (1993) reminds me of similar work by He You-Zhi, ‘Long Tong Life in Old Shanghai’. Please discuss?

In my work, I am often influenced by my direct surroundings. In addition, I have always been attracted to the use of perspective. Therefore, in some of my earlier work, you can see a mixture of Lingnan and Western schools as, for example, in my work Old Street in Sanxia, which I created while I lived in Taiwan in 1993. .

Sanxia is a village in Taiwan, which was strongly influenced by European culture. In a historical context, Sanxia is similar to Old Shanghai in China. I can see how my work Old Street in Sanxia reminds you of He You-Zhi’s ‘Long Tong Life in Old Shanghai’.

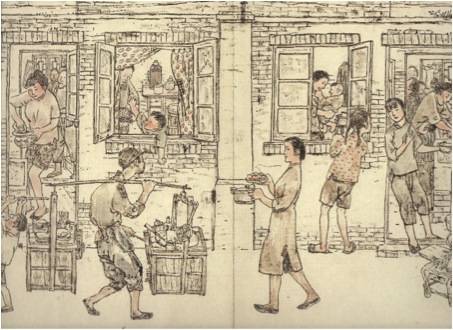

He You-Zhi’s ‘Long Tong Life in Old Shanghai’.

Your work centers around the exploration of Chinese Ink Painting. This brings with it great historical skills and techniques. Can you discuss one aspect: ‘Brushes’ the different shapes, sizes and hairs that you use?

In the Chinese ink painting, the quality of the brush stroke carries tremendous importance. It has to be strong and controlled, yet dynamic, fluid and delicate. Painting on mulberry paper with watery ink requires absolute mastery of the medium, because mistakes cannot be corrected. Any errors are unforgiving; the moment a brush touches paper, ink is absorbed and what has been painted cannot be undone. Consequently, in this medium, free expression can only be achieved through mastery of the medium and techniques. More than a thousand years ago, Chinese landscape painter, Kuo Hsi (ca. 1020-ca.1090) summarized this up as: “a painter should be master over, and not a slave to, his brush and ink.” The quality of Chinese brushwork is another aspect that makes ink painting so special to me.

There are mainly three types of brushes that I use; soft brushes made of sheep’s hair, mixed hair brushes made of deer and wolf hair, and hard brushes made of horsehair. I use various sizes and shapes of these brushes in my work, depending on the subject matter and expression that I wanted to achieve in my painting.

You sometimes teach and demonstrate Chinese Ink Painting. Can you discuss the importance of explaining this technique to both other artists and others interested in the arts?

In looking at ink painting throughout Chinese history, I find the depth of content and the strong personal connection the painters had to their subjects deeply fascinating. The renowned Six Dynasty Southern Song (375-443) landscape painter and philosopher, Zhong B’ien said: “I am here surrounded by creation, my eyes see the things that surround me, that’s why I paint the shapes captured in my heart, that’s why I paint the colours I feel in my heart.”

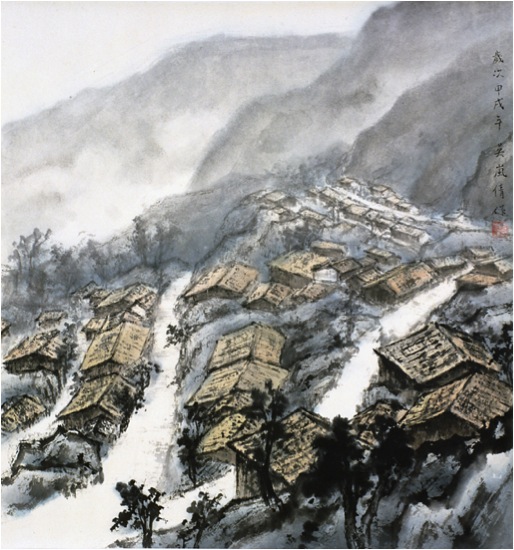

For me, the essence of Chinese ink painting remains exactly as the ancient masters described it; not an actual representation or an imitation of nature, but rather nature represented through how the painters experienced it through their souls. The intellectual painters of China made a conscientious effort to represent nature according their own values and aesthetic principles. In each of my paintings I develop a meaningful relation with the subject matter, and express my response with ink on paper. I consider my work sometimes as “mindscapes”. For instance in my 1994 painting Memory of My Roots, the scene is of my grandmother’s birth village. I was always very close to her, and the subject is therefore deeply personal. However, I did not paint the actual village, but rather how I felt the connection with this special place.

‘Memory of My Roots’

So, when I speak to people about my art, this is the very essence of what I want to convey.

One of your earliest talks was related to ‘Imaging the Orient’ at the J Paul Getty Museum in LA. Can you briefly discuss this topic?

In 2005, I was invited to give a ‘Point-of-View’ artist talk to discuss the ‘Imaging the Orient’ exhibition at J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. ‘Imaging the Orient’ was quite a fabulous exhibition. It showed how the visions of exotic lands fed the imagination of 18th century Europe. The exhibition explored how European artists were influenced by Asian art. They adapted motifs in imaginative and whimsical ways to produce Chinoiserie, a French term for objects that are decorated with Western fantasies of the exotic East.

I was particularly fond of discussing a pair of ewers (Chinese porcelain with French mounts, about 1745-1749, the maker unknown). These two Chinese vases were enriched in Paris with gilt bronze mounts to adapt them for a fashionable French interior. As I had discussed with the audiences, the original objects were two hard-paste Chinese porcelain vases with minimal decoration; simplicity and elegance from the height of the Qing Dynasty. The heavy and highly decorative French mounts completely changed the intent of the original maker. I found the different cultural aesthetic values and needs deeply fascinating.

How do you view linking the past and present, through your art?

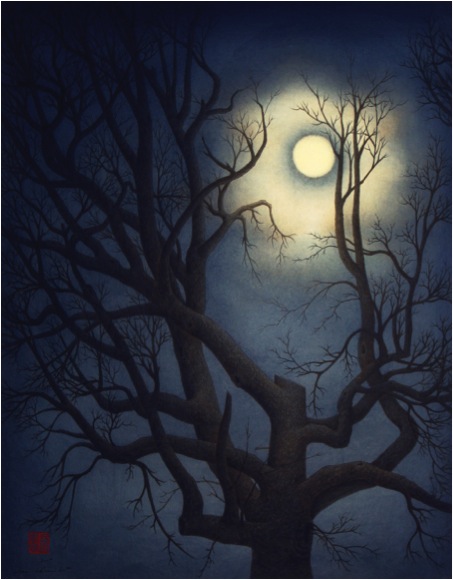

I have always been fascinated by the universal values and principles of life that are inherent to every society. Over the past two decades, I have created a body of work inspired by themes that connect people across place and time. My paintings are often inspired by the work of others, who share similar values, for example, in a poem, a story, or a novel. A good example here is a painting I made in 2009 that is based on Night Thought, a poem by Li Bai (701-62).

“A bright moon shines before my bed,

I wonder … is it frost on the ground?

I raise my head and gaze at the moon,

then lower it and think of home”

I named this painting Li Bai’s Moon. As Northern Sung dynasty Landscape Painter Kuo Hsi said, poetry is a picture without form and a painting is a poem with form. When I read Li Bai’s Night Thought, I wanted to picture his poem, as his words vividly described an image before my eyes. Night Thought emphasizes the umbilical connection that we have with our roots; it is a universal theme. What really captured me is that after 1300 years, the poem’s meaning still remains current, as we will always be connected to our roots no matter what century we live in.

‘Li Bai’s Moon’

Your work is not restricted to China and Taiwan as seen in ‘Reflections of the Past’. Please discuss?

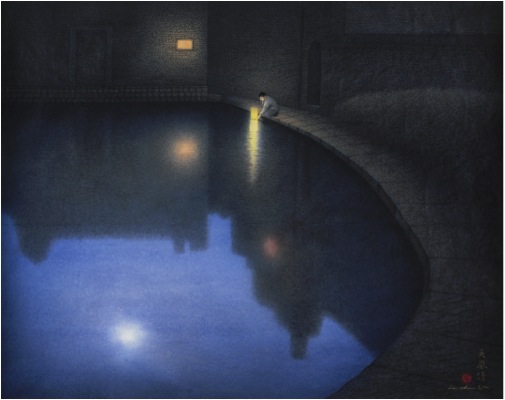

The recurring use of light, or sometimes only glimmers of light, in my work are metaphors for human resilience: the love, hope, and strength that we each person carries within. It is a central theme in my art. My painting Reflection of the Past (1999) is a good examples. Resilience is an innate strength we all share, which helps us during each phase of our lives.

‘Reflection of the Past’

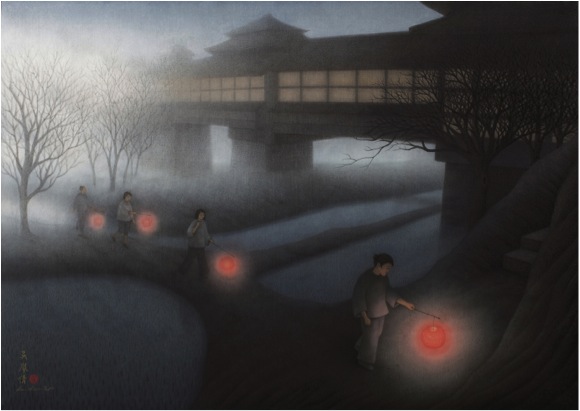

Reflection of the Past was inspired by the Japanese summer festival of remembrance, called O-Bon. O-Bon is an annual reminder of the importance of family ties, of respect for those who have gone before us, and of the brevity and preciousness of our lives together. Japanese people welcome home of the souls of deceased family members by floating paper lanterns on water. I am keenly aware that everyone carries within his or her souls memories of past love ones like precious glowing lights, see for example Precious Light (2012). I believe that it is a universal feeling that I expressed with these painting through the use of lit lanterns.

‘Precious Light’

Discuss your work in relation to distance that separates you form your birthplace?

Much of my inspiration comes from daily life, but always centres on universal humanistic values and themes. In my work, I seek to create a connection between people and place. My creative ideas often inspired by my direct environment, such as when I lived in New York. For example, my painting Snowflakes Quietly Descending (1999) was made in Manhattan, New York City, where I then lived.

‘

Snowflakes Quietly Descending’

‘Snowflakes Quietly Descending’ does not appear Asian, but still it gives this feeling, could you explain this?

The painting Snowflakes Quietly Descending is a view of Fifth Avenue looking south from the Guggenheim Museum on 89th Street. In this particular painting, I aimed at capturing a quintessential New York City ‘landscape’ during a light winter storm. I used to live close to the Guggenheim, and the painting expresses my love of the city. A Broadway actor, who lives on the Westside, collected Snowflakes Quietly Descending, and I feel therefore that a part of me never left New York.

I stood in the snow and watched the snow falling on me for several days. I was observing the scenery, making sketches, taking notes, and was experimenting with painting techniques. Then, I brought my study materials back to my studio to complete the composition. The original work is quite large, so when you stand in a certain angle it is as if you can walk into the avenue. While I captured the scene on Manhattan, I developed a feeling for the city analogous to how painters of the past described their connection to places, such as philosopher Zhong B’ien said in the 5th century

‘Li Bai’s Moon’

Another good example here is a painting I made in 2009 that is based on Night Thought, a poem by Li Bai (701-62). For this work, I sketched an old tree that I walked by every day here in Los Angeles.

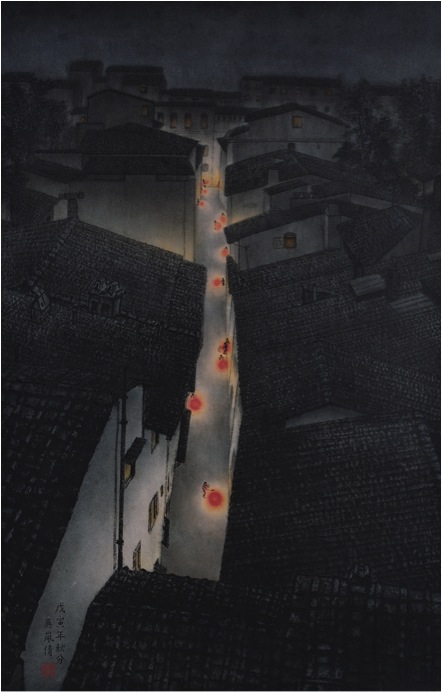

Could you discuss ‘Lantern Festival I’ in relation to darkness and light?

My painting Lantern Festival I, which I made after a visit to Florence in 1997. Fascinated by the architecture of the city, I made several sketches looking down from one of the widows of Palazzo Vecchio. To express my special feeling for the city, I tried to give this painting a mesmerizing quality by creating a night scene. I tested this effect with charcoal and a basic composition, before I completed this painting. During the creation of this work, my imagination brought me to my childhood’s favourite festival in Taiwan. At that particular moment, I realized that no matter which city (East or West) you visit, a city’s energy is universal, and that is what I wanted to express in Lantern Festival I. This painting too, shows my interest in perspective and light, and illustrates that I make conscious connections between people and place across cultures.

‘Lantern Festival I’

Your project, ‘Cycle of Life’ is to consist of sixteen paintings. Could you explain the project and its basic concept, and elaborate on the relation to the four seasons and the stages of human Life?

Inspired by John Keats’s sonnet The Human Seasons, Cycle of Life will consist of sixteen large-scale ink paintings, designed as four groups of four paintings each. Each group represents one season of nature, which I will use to juxtapose the human stages of life.

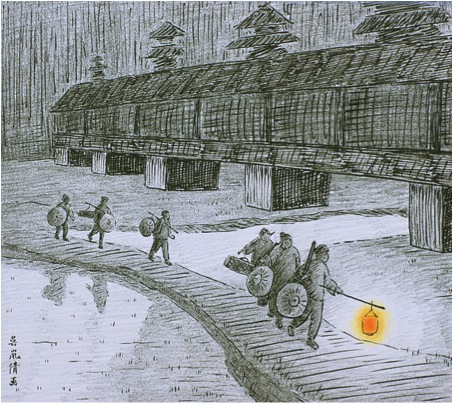

In Cycle of Life, I will explore the human seasons to create a visual context for the different stages we pass through in life. In this project, I will use the rhythm of nature as an allegory for the human cycle of life. That said, I envision the season in my very personal way. For example, I may imagine Spring, as human beings coming to this earth with unknowing destinies, similar to an early morning that announces a day filled with expectation. To explore this idea, I used my sketch Leading the Way Home (2004) as a base, and developed it into a study for Spring called A New Dawn.

‘Leading the Way Home’

Spring: Birth and Renewal

Spring: Birth and Renewal;

Summer: Exploration and Growth

This stage of life is a playful period of exploration and growth. Youth is attracted to different directions and wants to experience life in many ways.

Autumn: Maturity and Confidence

Autumn is the golden stage of life. This is the time of accomplishment, but it may also be turbulent as the last stage is approaching.

We come to this earth alone and depart alone. This is time for reflection, for looking back, and perhaps contemplate afterlife.

We come to this earth alone and depart alone. This is time for reflection, for looking back, and perhaps contemplate afterlife.

John Keats’ The Human Seasons has great depth:

“Four Seasons fill the measure of the year;

There are four seasons in the mind of man:

He has his lusty Spring, when fancy clear

Takes in all beauty with an easy span:

He has his Summer, when luxuriously

Spring’s honied cud of youthful thought he loves

To ruminate, and by such dreaming high

Is nearest unto heaven: quiet coves

His soul has in its Autumn, when his wings

He furleth close; contented so to look

On mists in idleness—to let fair things

Pass by unheeded as a threshold brook.

He has his Winter too of pale misfeature,

Or else he would forego his mortal nature.”

Keats’ poem evokes several strong images with me, and I have begun with laying out ideas for individual paintings and finished several study paintings, and I am preparing sketches for the overall work.

While the work is in progress, I will also be developing exhibition ideas and programs for Cycle of Life with the local, national and international communities. To-date, I have spoken about my work and sources of inspiration at the Southern California Historical Society in Los Angeles, presented on the same subject at the Huntington Library in San Marino, and at Bowdoin College in Maine. It is an ambitious project for which I am seeking external financial support, and I hope to complete the entire series of paintings by the end of 2015.

‘A New Dawn’

Are you working through the series in a chronological order?

I am not working on the paintings in chronological order. I explore visual ideas when they come to me, which can be in any order. But I do have the larger picture in mind and I will fit each component together like pieces of a puzzle. It is a process I tremendously enjoy, but it is also challenging because of its scale.

Could you explain the involvement of NYFA, and NYFA as an organization?

Cycle of Life is a sponsored project of ARTSIPRE, a Program of the New York Foundation of the Arts (NYFA), which acts as fiscal sponsor for the project. Many people think that ARTSPIRE or NYFA commissioned Cycle of Life, but this is not the case; they provide fiscal sponsorship. Sometimes, people or organizations are reluctant to support artists directly out of concern for lack of oversight on how their funds are expended. As fiscal sponsor, ARTSIPRE guarantees that any donations to the project (thus not directly to the artist) are used for eligible expenses. It is a great way to support artists with making projects they cannot fund themselves.

ARTSPIRE is a 501(c)(3), tax-exempt organization founded in 1971 to work with the arts community throughout the United States to develop and facilitate programs in all art disciplines. ARTSPIRE receives donations and grants on behalf of Cycle of Life, and ensures that the use of grant funds is in compliance with U. S. regulations. ARTSPIRE provides program or financial reports as required. As project director and independent artist, I will be responsible for executing and overseeing the project. My work will include: executing the art project and overall project management, expanding professional networks, working with external consultants, outreach, etc.

Recently, you worked very closely with Wu Man. Can you expand on this connection and also the connection with the Huntington Library, Art Collection, and Botanical Gardens?

Wu Man and I are interested in expanding the appreciation of traditional Chinese culture in a contemporary context. In 2012, when June Li, Curator of the Chinese den at the Huntington heard that Wu Man and I wanted to collaborate on a project that involved Chinese painting, music and poetry, she was keenly interested to work with us. June invited us to give a talk as part of a special public program at the Huntington. Our presentation was called: “An Evening with Wu Man and Lan-Chiann Wu” held on June 18, 2013.

‘Wu Man & June Li, with Lan-Chiann Wu’

At the event, Wu Man and I shared what inspires us to make art in our respective disciplines, and gave demonstrations of our art forms. We were sharing how we transform poetry into painting and music, especially because we had discovered that we both created a work inspired by 8th century poet Li Bai. I am referring to Li Bai’s Night Thoughts. It is a poem that all Chinese children have to learn when they are in second or third grade; they have to remember it by heart. When you are very young, those words don’t really mean a lot to you. You have to recite it and that’s it. But after you move away from your home, or in my case, immigrate to another country, the poem takes on a poignant meaning.

So when I re-read Li Bai’s Night Thoughts his words made a deep impact on me. When we discussed the poem at the Huntington event, it also resonated strongly with the audience. After the lecture, many people expressed to me that they felt uplifted and inspired to further explore Chinese culture. The Huntington has released a video recording of An Evening with Wu Man and Lan-Chiann Wu. They captured the entire event, and its complete footage can be found on YouTube:

Our humanity, our core values and principles, is what binds us together as one people across time and space, and this is the main theme in my art. Therefore, my paintings are not mere images; they are layered with content and represent universal themes that each and all of us experience in life. As a visual artist, I enjoy sharing my vision through my painting as well as through speaking about my art.

Contact details.

Lan-Chiann Wu

Website: www.thetranquilstudio.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/TheArtofLanChiannWu

Cycle of Life:

https://www.nyfa.org/ArtistDirectory/ShowProject/caeb6d9f-f3da-47be-99ec-f5b82147f964

Lan-Chiann Wu, California, USA

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June 2014

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: