Eleanor Lakelin Wood Artist - London, UK

What lead you to work with wood?

I grew up in a very rural part of Wales surrounded by hills. Roaming through woods collecting natural things, particularly gnarled wood coloured and textured by time and the elements, was a big part of my childhood. After teaching in various countries in Europe and Africa, I retrained as a furniture-maker between 1995 and 1998. I then worked for many years making theatre sets and designing and making furniture. In 2011 I changed my practice to concentrate on creating sculptural vessels and objects in wood – work informed by those early experiences looking at natural processes and landscape.

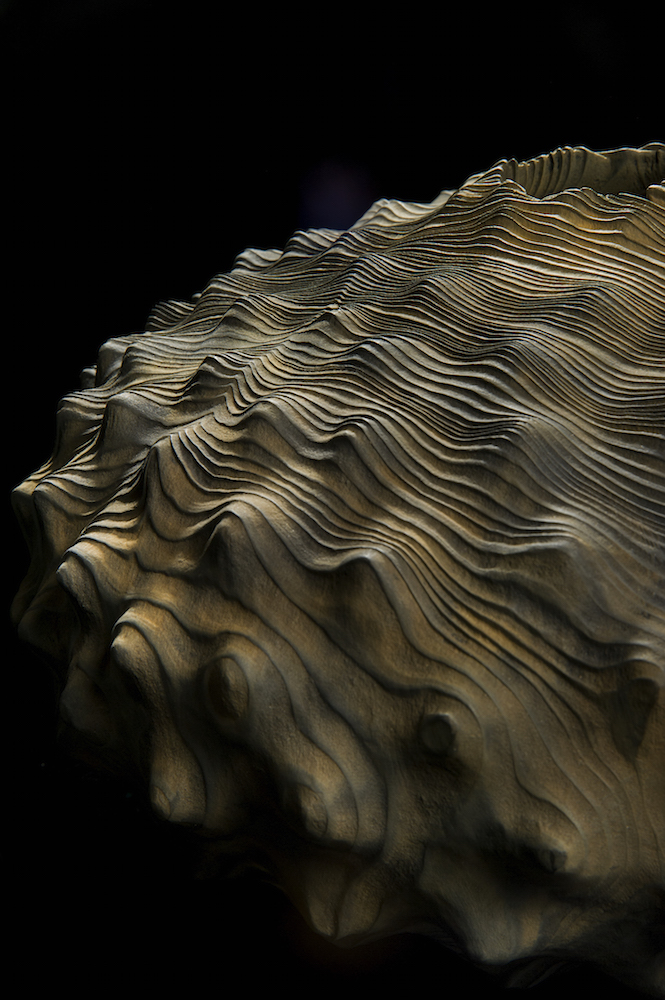

Ferrous Shift, detail, Photo Ester Segarra

You use trees felled in the British Isles – How do you become aware of trees that are either coming down or are down?

Locally, tree surgeons phone me or drop trees off but now that I mainly sell through galleries and tend to create pieces in a series, I have certain trees that I look for. I buy a lot of wood from a village sawmill next to a large country house estate which means a selection of large parkland trees that have had to be felled. I also spend a lot of time emailing forestry and arboreal companies to find particular burred wood I like to work with.

Void Vessels, Photo Jeremy Johns

Can you tell us about the work that went to British House Rio?

I was asked to make a collection of pieces that would be displayed at British House – the place to celebrate Team GB’s sporting performance and a cultural showcase for the best of the UK at Rio 2016. During the Olympics, British House was located in the centre of Rio de Janeiro at historic Parque Lage, adjacent to the iconic Christ the Redeemer statue and within the Copacabana cluster of the Games. Other artworks on show include a dramatic paper chandelier by Zoe Bradley as well as pieces by Theresa Nguyen, Insley and Nash and Alexandra Llewellyn.

Rio Olympics, Photo Jeremy Johns

I had recently started working with Sequoia, grown in Britain after the seeds were brought back from California in the 1850’s and recently felled due to decay. It seemed fitting to reimagine and recreate this material into pieces that would be returned across the Atlantic 160 years after the seeds arrived, reflecting something of the global nature of the event. The collection of eight vessels, linked by material but using different forms and texture, returned to Britain after the Olympics and were sold to collectors.

Rio Olympics, Photo Jeremy Johns

For your project with the National Trust –Discuss the Great Cedar tree and its historical importance.

I’m always fascinated by the provenance of my materials and how this shapes my process and work. In the summer of 2014, a great cedar tree planted by the Duke of Wellington in 1827 had to be felled at the National Trust property Kingston Lacy. I was asked to create a collection of vessels from this beautiful, historical tree, to mark the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo in June 2015.

Where are the three pieces that were added to the National Trust Collection?

An open bowl form and two hollow carved forms were purchased to be displayed at Kingston Lacey, the National Trust Property where the tree was planted. The works are showcased as part of a collection in the Spanish room of the house, as apparently it was during his time in Spain that the once Lord of the Manor, William Bankes, collected Art and cemented his friendship with the Duke of Wellington.

National Trust Commission, Photo Stephen Brayne

How many pieces were you able to make from this one tree? I made between eight and ten pieces including a very large piece called the Wellington Bowl which was part of an exhibition called ‘Bowls of Britain’ in 2015.

What drying process had to take place before you could commence?

The tree had already been felled some time before but was still relatively green. I turned the pieces quite thin so that they would dry quickly as by the time the project was agreed and organised, there was very little time before the Bicentenary celebrations in June 2015.

What happened to the other pieces you made?

All of the vessels were sold. The smaller pieces were made available to purchase from the National Trust with proceeds helping to fund conservation works at Kingston Lacy.

Discuss your personal thoughts on history being kept in a contemporary art form?

It is not unusual for contemporary art to look to the past for ideas, inspiration or designs whether they be used to agitate for change, to look at differences or ways forward in the present. Much of what I do is about material and stories – visualising an idea in a form. This was an interesting material and a great story.

Expand on how and where you keep your wood?

Ferrous Shift, Photo Ester Segarra

I keep wood everywhere – in sheds behind my studio, in the car park, in my workshop, in storage, behind the saw, on the shelves, in my garden, in my basement, in my garden shed, wrapped in cotton, wrapped in plastic, under tarps, under beds – it’s an obsession . . there is no end . . .

What is one special tool that you love working with and why is it so valued by you?

It is almost impossible to choose one tool but I suppose my lathe is the most central tool to my work at the moment. I spend ages carving off the lathe and sandblasting or scorching wood but the lathe is where I start with hollow sculptural vessels. For most pieces I use a Vicmarc lathe, manufactured in Queensland, Australia – it is very old, very heavy with no frills but reliably does what is needed.

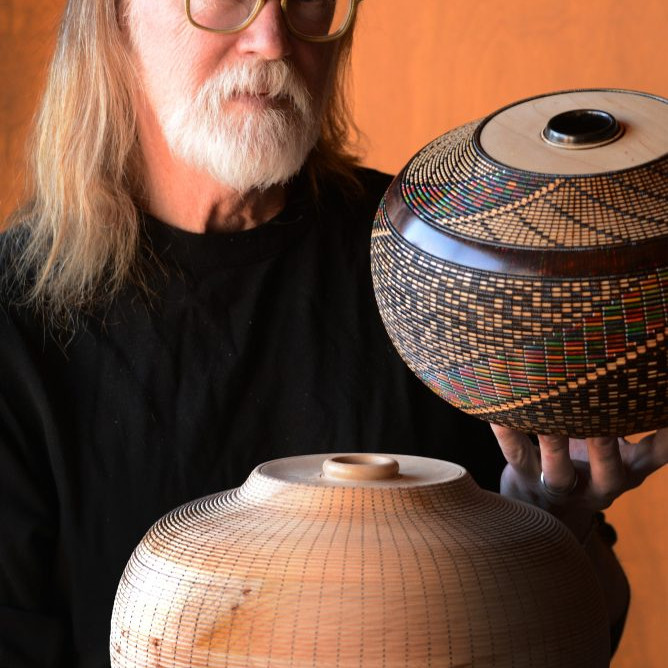

Eleanor Larkelin, Photo Alun Callend, Courtsey of Cockpit Arts

What information do you provide with each piece?

My work is mainly sold through galleries but if people are interested I provide them with information about the provenance of the material, its age and properties, techniques used and the inspiration behind the pieces.

Void Vessels, Photo Jeremy Johns

Your comment, “I’m fascinated by wood as a living, breathing substance with its own history.”

I’m particularly inspired by the organic mayhem and creative possibilities of burred wood, which I work with exclusively for the ‘Contours of Nature’ series. This proliferation of cells, formed over decades or even centuries as a reaction to stress or as a healing mechanism is a rare, mysterious and beautiful act of nature. The twisted configuration of the grain and the frequent bark inclusions and voids are challenging to work and the forms difficult to hollow but the removal of the bark reveals a secret landscape, unseen by anyone before.Wood grows at a different density during different times of the year. In the Time & Texture series I sandblast across the surface to create a kind of speeded-up erosion. Time itself feels etched into the fibres of the material. By carving to different depths within the piece and then sandblasting through another layer, a moving, sinuous pattern is created which speaks of natural movement – of wind, sand, rhythm, flow and of time.

Expand on your work in relations to large installations?

I’ve been exploring working at a larger scale and I was thrilled that my Time & Texture Installation at Forde Abbey recieved a Wood Award, within the ‘Bespoke’ category. The works formed part of ‘A Landscape of Objects’, a site-specific exhibition set in the gardens of Forde Abbey, curated by Flow Gallery. The brief was to reference both the shapes, colours and texture of the gardens and buildings and the importance of water on the site.The installation was formed of three hollowed vessels on rusted plinths and four solid forms designed to show how natural elements erode and work away at materials. Through building up layers of texture through carving and sandblasting away the softer wood, it is possible to show how natural elements and processes layer and colour wood. The sequoia and sycamore vessels were turned on a lathe and hollowed out through a small hole. The four solid pieces are sculpted from English oak and cedar and the spherical form was chosen to reflect the natural shapes in the garden and in the landscape.I’m keen to explore Installation ideas further and have an invitation to visit sculptor Mark Lindquist’s studios in Florida to explore a new body of larger scale works.

Explain on your pieces ‘Basaltes Vessels’ and the rock formation you based this work on.

Basaltes, Vessels, Photo Jeremy Johns

Also part of the ‘Time & Texture’ series – these new, elongated forms are turned and carved in a freer way using an angle grinder and chainsaw wheel. A natural ‘slate grey’ tone is drawn from the wood using an iron solution (iron being a property of Basalt) or the wood is ‘pickled’ white.Basalt is a fine-grained, igneous rock which makes up a significant part of the oceanic crust. The distinctive columnar topology or ‘fractures’ are created during the cooling of a thick lava flow – forming a ‘random cellular network’. Basalts weather and erode relatively fast compared to other rocks and the typically iron-rich minerals can oxidise rapidly in water and air.The pieces were created not necessarily to look like basalt but to give a sense of the erosive power of natural elements as they texture, colour and break down material over time.

Contact details:

Eleanor Lakelin

eleanor@eleanorlakelin.com07944 811675Studio 011

Cockpit Arts

18-22 Creekside

London

Eleanor Lakelin, London, UK

Interview by Deborah Blakeley, June 2018

Think a colleague or friend could benefit from this interview?

Knowledge is one of the biggest assets in any business. So why not forward this on to your friends and colleagues so they too can start taking advantage of the insightful information the artist has given?

Other artists you may be interested in: